Executive Summary

Whether due to fears of the next bear market, a struggle to differentiate in an increasingly crowded AUM-fee landscape, or the pressure of competition from robo-advisors, a growing number of financial planners are talking about changing from the assets under management (AUM) model to adopting some form of (typically annual) retainer fees instead.

While the AUM model has challenges, though, from revenue volatility to potentially misaligned pricing for clients to non-trivial conflicts of interest, the ongoing rise of the AUM model suggests that it still has more benefits than drawbacks. And in fact, its biggest strength from the business model perspective – the ability to have revenue per client grow over time as the market grows – may be a key factor that allows it to continue to dominate the more-salient retainer fee alternative, which may struggle to keep pace with rising employee advisor costs given the industry’s demographic shortages.

Yet the reality is that the greatest potential for retainer fees may have nothing to do with competing head-to-head with the AUM business model, but instead to reach out to clients that the AUM model can’t serve in the first place – as many as perhaps 80% of all households, that simply don’t have available assets to manage (or sufficient assets to be managed in the first place). In fact, the untapped market potential for using retainer fees to expand the reach of financial planning is so large that, in the long run, while the AUM model may still survive, it could become a niche for high-net-worth clients, while most consumers access financial planning through various retainer or fee-for-service alternatives!

The Challenge Of AUM Fees And The Virtue Of The Financial Planning Retainer Fee

The growth of the AUM model has been tremendous over the past decade; while in its initial years in the early 2000s, the Moss Adams advisor benchmarking survey indicated the average firm had just $25M of AUM, by 2008 the typical firm was over $100M of AUM, and in 2013 the latest version of the study showed the average firm over $200M of AUM. Yet despite the tremendous ongoing growth of the AUM model, an increasing number of industry commentators are raising the question of whether there is trouble ahead (or as Bob Veres recently wrote, “The AUM Fee Is Toast”).

Aligning Pricing With The Value Of And Cost To Deliver Financial Planning Services

Perhaps the biggest criticism of the AUM business model in today’s environment is that it’s not an effective alignment between the pricing model and the value that an advisory firm typically provides today. In particular, as technology increasingly commoditizes investment management (especially the passive strategic investment strategies popular with many RIAs), and firms increasingly find themselves trying to deliver more and deeper financial planning services as a value-add (or the core value!) to differentiate themselves, the question arises as to why firms are still using a “portfolio-centric” pricing model for a financial-planning-centric value proposition. By contrast, a (comprehensive) retainer fee that is separate from the portfolio can more squarely place the client’s focus on the (comprehensive) beyond-just-portfolio financial planning services.

In addition, not only does the portfolio-based pricing model potential misdirect client attention towards the portfolio and away from the financial planning services, but it also risks misaligning revenue and cost. As critics are quick to point out, the actual complexity and amount of work involved for a client is not necessarily related to their level of AUM – at best, it is perhaps a crude approximation that a multi-million-dollar portfolio owner probably has a somewhat more complex financial situation than someone with just a few hundred thousand dollars of net worth (who in turn is 'more complex' than someone with even less in investable assets). In other words, someone with an $800,000 portfolio might have a little more complexity than someone with a $400,000 portfolio, but probably doesn’t have twice the complexity (and time/effort to service), despite being charged twice as much under an AUM fee structure (or perhaps just slightly-less-than-double with a graduated fee schedule).

By contrast, when a retainer fee is established, it’s easier to align the pricing of services with the cost for the business to deliver those services (which matters, since professional staffing costs are the largest line-item expense of an advisory firm!). For instance, a standard client service calendar can be established, that stipulates the exact services clients will receive throughout the year, and be priced in a manner that’s appropriate for the number of hours it will take to consistently deliver the service; in other words, if the particular client service calendar typically takes 20 hours of work to deliver throughout the year, it can be priced based on the cost to deliver 20 hours of work, rather than based on a client’s assets that may have little relationship to the work being done.

And if the firm serves a wide range of clients with a wide range of assets/income/net worth, offering multiple levels of services of varying complexity can be accomplished by crafting segmented service tiers for clients, which still articulate exactly what services clients will get at each tier; clients can then select the tier of services their want (and are appropriate for their needs), and the firm can remain confident that the service will be priced appropriately for the time/effort/cost to deliver. (And for clients with truly unique and exceptional situations, the advisor can always adjust the retainer fee to match the reality of that situation, in a manner that is typically easier and more flexible than trying to change a client’s AUM fee schedule on the spot to accommodate a situation.)

Revenue Volatility Of The AUM Model Vs Stable Retainer Fees

Beyond the mismatch between client AUM fees and the staff time (and therefore cost) it takes to service them, there’s also the problematic reality that client needs are not stable over time, and clients may be relatively hands-off in some years, but then need the most service and hand-holding after a bear market occurs.

And of course, in the midst of a bear market when client service demands peak, AUM fees decline as the portfolio declines, which means the firm ends out facing the greatest client demands on its staff at the exact moment it's generating the least revenue to compensate them! In turn, this can put an especially harsh squeeze on the profits of an advisory firm, as revenue declines but staff costs remain, since it is viewed as ‘business suicide’ for most advisory firms to lay off staff in the midst of a bear market (where firing staff to save costs leads to reduced service for clients at the exact time they need their advisor most, which in turn can result in a spike in client attrition that just causes revenues to decline even further as clients walk out the door!).

By contrast, retainer fees are not tied directly to the portfolio account balance, and thus can remain stable through bear markets, eliminating the challenge faced by the AUM model to manage the business through what can be highly volatile fluctuations in revenue. In other words, firms following the retainer fee approach don’t need to worry that the ‘dangerous’ market timing misalignment of the AUM model, where revenues decline in a bear market at the exact moment that clients demand the most service and support, and instead can be more confident that the revenue will be there to pay the advisors needed to handhold clients through a scary market situation!

Retainer Fees To Solve AUM-Fee-Based Conflicts Of Interest

Another popular criticism of the AUM model is that it still embodies several very problematic conflicts of interest. When the advisor is paid primarily (or exclusively) for managed portfolio assets, there is a classic disincentive to advise clients in strategies from paying off a mortgage to “non-portfolio” investing strategies like direct real estate purchases to entrepreneurs reinvesting into their businesses. And in an increasingly retirement-centric financial planning world, AUM fees are finding ‘new’ conflicts to manage, such as delaying the currently-mispriced Social Security retirement benefits (which may be financially superior in the long run but in the short term causes clients to withdraw more from the portfolio while waiting until age 70), or the use of immediate annuities as a mortality-credit-enhanced fixed income alternative for retirees (which may make sense for certain retirement income scenarios, but also reduces advisor AUM in the near term as funds are withdrawn to buy the annuity).

By contrast, the retainer fee model avoids many of the inherent conflicts of interest embedded in the AUM model. When client fees are determined independent of whether/how much of the portfolio the advisor manages, there is no more financial incentive for the advisor to give advice that preserves one type of asset (the portfolio) over all others. When the advisor’s compensation (based on the retainer fee) is the same, regardless of whether the client liquidates the portfolio to pay down mortgage or other debt, or to invest in real estate, or to (re-)invest into an entrepreneurial endeavor, there is no longer a conflict of interest to provide prudent advice with respect to those assets.

Of course, there can be some good reasons not to pay off a mortgage, invest in real estate, or keep plowing money into the next (or current) entrepreneurial adventure… and plenty of advisors under the AUM model still counsel clients to delay Social Security, or pay down a mortgage, or invest in a new business. A conflict of interest doesn’t automatically mean that the advice delivered under the AUM model will be “wrong” and that the advisor will succumb to the conflict (and arguably, these conflicts are still ‘less severe’ than those posed by selling high-commission financial services products). Still, the changed incentives of the retainer fee model clearly reduce the potential influence the conflict of interest could wield over the advisor.

The Problems With Retainer Fees (Vs AUM Fees)

Notwithstanding the purported benefits of retainer fees over AUM fees, it’s important to note that there are several very important caveats to consider when it comes to using retainer fees in lieu of AUM fees.

Revenue Stability Of Retainer Fees – In Bear And Bull Markets

While the stability of retainer fees in a bear market can be helpful to navigating what would otherwise be declining AUM-fee revenues, it’s crucial to note that the stability of retainer fees applies in bull markets as well. In other words, the good news is that the fee won’t go down when the markets go down, but that also means the fee won't automatically go up when markets are up.

And given that markets are up far more often than they’re down, arguably there’s a significant risk in adopting retainer fees that the business will leave significant revenue growth on the table. After all, converting from an AUM advisory firm to a practice that uses retainer fees is like shifting the firm’s revenue to go from being “stock-like” (tied to markets) to “bond-like” (tied to flat retainers) instead. And as we know, stocks go up more often than they go down, and outperform bonds in the long run on that basis (notwithstanding the volatility along the way).

So if we tell our clients – even those retired taking ongoing withdrawals – to invest in at least a moderate amount in stocks and ride out the volatility, because it produces greater wealth in the long run, shouldn’t we take our own advice when it comes to keeping the revenue of our own advisory firms hooked to long-term stock market growth, too? Or viewed another way, yes AUM fees are volatile – and that risk is rewarded with a return premium that allows AUM fees to grow at a faster pace than bond-like retainer fees! And as with portfolios taking distributions, volatility doesn't have to be avoided but instead can be managed on an ongoing basis, from more flexible compensation structures for staff, to having a cash buffer or a line of credit for the business, or using stock options as a revenue hedging strategy for the business, or simply ensuring the firm has sufficient profit margins to absorb a temporary revenue decline in the first place!

The problem of giving up market-based AUM fee growth for a fixed retainer fee is further complicated by the fact that the industry continues to face a significant demographic shortage of young advisor talent, even as more and more advisory firms hire employee advisors to service clients – which means the typical salary for advisory firm employees is growing rapidly. According to the 2013 Moss Adams Investment News Compensation And Staffing study, median compensation for Level 2 Service Advisors was up 8% over the preceding 2 years, and compensation for lead advisors was up 12%. Which means the advisory firm’s greatest line item expense is growing at an annualized rate of about 5%/year, even as retainer fees keep revenue flat (not declining, but not rising either).

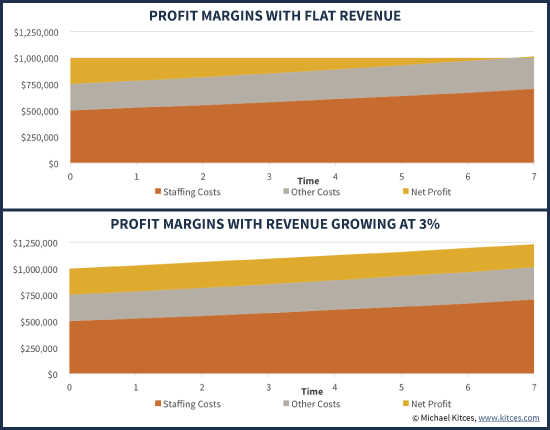

The end result – even a highly profitable firm may find its profit margins chopped down to almost nothing in the next 7 years, as the chart shows below. (Michael’s Note: Chart assumes professional planning staff costs are 50% of total revenue, and rise by 5%/year, while other expenses add up to 25% and rise at 3%/year for inflation, and client revenue in the form of either flat-revenue retainer fees, or AUM-based fees growing at a conservative net-of-withdrawals rate of 3%/year.)

This suggests that at a minimum, advisory firms that look to a retainer fee structure need to figure out, in advance, how to build in automatic increases to retainer fees, just to have a chance to keep pace with the AUM business model, or risk a severe profit squeeze. Especially since if increases aren't automatic as a part of the retainer fee contract, a fee adjustment will require a new conversation with the client, every year, about raising that fee – a conversation that can be awkward for the advisor as well as the client, and lead to potential pushback (such that the retainer fees don't even grow at a pace that keeps up with inflation!).

In practice, many firms I know that have adopted the retainer fee only make adjustments every 2-3 years, for this exact reason – except that means revenue rises even more slowly (if it does at all!). And of course, in reality a mere net-3%-per-year growth rate is arguably still quite conservative for most AUM-based advisory firms, which means even escalating retainer fees by a few percent per year (or only every few years) will make it even more difficult for the firm to grow and reinvest. The last resort for some may be to simply get increasingly affluent clients who can afford to pay larger fees (and replace the "smaller" clients), but given a limited number of high-net-worth households not every advisor can pursue this strategy!

Saliency Of Financial Planning Fees

The fundamental problem of retainer fees is that they are more salient – the need to discuss them regularly makes them “top of mind” and naturally invites the client to push back on the fee and ask “what have you done for me lately” – which means in practice, it is very difficult to regularly raise retainer fees even to keep pace with inflation, much less to parallel the market growth of an AUM fee. By contrast, AUM fee adjustments happen automatically because they’re already tied formulaically to the portfolio, in a manner that doesn’t require a new conversation annually. Accordingly, it’s no coincidence that notwithstanding the damage that the 2008-2009 bear market did to bring AUM fees down, AUM-based firms have long-since rebounded to new highs since then, on the back of the subsequent bull market.

On the other hand, while the saliency of bringing up a retainer fee every year can make it harder to raise the fee in a bull market, clients may still feel compelled to ask for a fee cut in a bear market! After all, while the fee might not automatically decrease as the AUM declines (the "stable revenue" benefit of retainer fees during bear markets), clients who are feeling less wealthy in the face of a bear market may still ask for a fee cut, or otherwise become more fee sensitive as they look for places to “save” on expenses! Especially since an AUM-based advisor up the street may offer to work with the client for less – charging an AUM fee on the now-reduced portfolio – recognizing that a future market rebound means the client can still be profitable over time!

Example. In the interests of promoting revenue stability, Roger converted his client Catherine, who was paying a 1% AUM fee on a $1,000,000 portfolio, into a $10,000/year retainer client instead. In the following year, a severe bear market ensues, and Catherine’s portfolio falls to only $700,000. As a result, Catherine the client asks for a cut in her fees, noting that her $10,000/year retainer fee is now 1.4% of her reduced portfolio.

At the same time, an advisor up the street named Andrew solicits Betty to become his client instead, noting that at his 1% AUM fee, he would charge only $7,000 (which is 1% of the now-reduced $700,000 portfolio), a whopping 30% less than Roger! Andrew may be willing to do this, in part because he knows that his $7,000 fee can grow over time as the market rebounds from the crash and rises in the future, allowing Catherine the client to become a profitable client for him in the long run, and giving Andrew's business the ability to reinvest and continue to provide her more services.

Yet now Roger the retainer advisor is left in a tough spot; he can either cut his fee to $7,000 to match Andrew the AUM advisor, knowing that it will be hard to raise the fee again in the future (and still taking a decrease in fees during a bear market, even though the whole point of the retainer fee was to avoid that!), or risk losing Catherine the client and her $10,000 retainer fee altogether!

The Difficulty Of Selling A Retainer Fee Firm

Another notable challenge of structuring a firm with retainer fees is that it can be more difficult to sell.

The first issue is that, since the AUM model will generally provide better growth in revenue per client (as assets grow over time), the natural upside of the model makes it more appealing to buyers than a flat-fee retainer model. This seems to be true even for firms that have a relatively "old" retired client base, as even with ongoing withdrawals, an AUM firm will generally still enjoy revenue growth because market returns still exceed withdrawals for the typical retiree in their 60s and 70s. By comparison, a retainer fee model that struggles to grow its revenue per client, and/or is facing a profit squeeze in the coming years as client revenue fails to grow at the same pace as staff raises, will simply end out with a lower business valuation, due to the implied lower growth rate assumption that gets included in any form of discounted cash flow modeling.

The secondary challenge of selling a retainer fee model is that it adds complexity for an AUM-based firm to buy a retainer-fee model - requiring significant changes to billing and other processes - which makes it less appealing to buy in the first place. By contrast, when an AUM firm buys another AUM firm, the process is far more straightforward - AUM billing is already the standard, and the only potential challenge is to merge what are already likely to fairly similar fee schedules. This dynamic means AUM firms are somewhat more likely to want to buy other AUM firms and that retainer fee firms are more likely to be purchased by other retainer fee firms. Except since there aren't many retainer fee firms in practice already, those who transition to retainer fee firms in the near future and hope to sell in the near future may find the market of buyers much smaller, and much less willing to pay appealing revenue/profit multiples for the business!

The Real Opportunity For Retainer Fees – The Blue Ocean Of Underserved Clients

Limited Market Size For The AUM Model

As noted, it may be more difficult than many retainer advocates realize for retainer fee models to really compete head-to-head against AUM fee models. But focusing on the competition between AUM and retainer fees misses what is perhaps the greatest caveat to the retainer model in the first place: that by definition, it only “works” for those who have assets to manage in the first place! Which as it turns out, is a somewhat limited portion of the population.

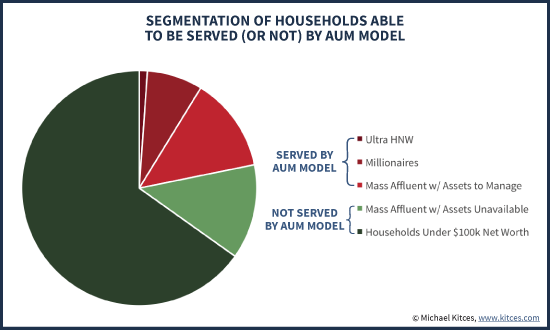

According to Spectrem Group, there are a little over 1.3 million “ultra high net worth” households (wealth over $5M), another 8.8 million “millionaire” households (with $1M to $5M of wealth), and almost 30 million “mass affluent” households ($100k to $1M of net worth). To put that in context, according to the US Census, there are about 115 million total households in the US. Which means put together, barely 1/3rd of all households in the US have enough assets to meet even a $100k asset minimum!

In addition, the reality is that a significant portion of mass affluent net worth is tied up in an employer retirement plan (e.g., a 401(k) plan), which means it’s still not available to manage currently; if we assume about half of mass affluent households fall into that category, then in total barely 20% of all US households could possibly be served by the ‘industry standard’ AUM model!

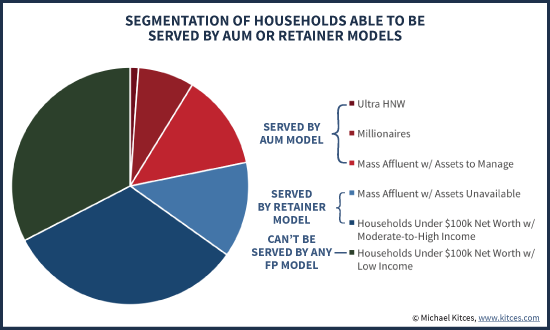

In this context, the key point is that retainer fees can potentially reach a wide swath of the population who can’t be served by AUM fees at all. In other words, the greatest opportunity of retainer fees may not be to draw away clients currently paying AUM fees, but to serve the other nearly-80%-of-households the AUM model can’t reach in the first place!

Of course, for a significant subset of these households, they simply won’t have the financial wherewithal to pay for any financial planning services – arguably, there is some minimum of income and net worth where financial planning services just have limited relevance or viability in the first place (perhaps the bottom 40% of households who just can’t afford any financial planning assistance?). Nonetheless, for many households, they do have either sufficient net worth and/or income to pay for financial planning services, and a need for them, they just don’t have assets to manage and want to pay for financial planning from cash flow instead. (Or alternatively, some may even have assets to manage, but still won’t adopt an AUM-based advisor because they just want financial advice separate from investment management services!)

Which means that ultimately, the number of households that have a financial wherewithal to pay retainer fees, but can't work with an AUM advisor, may actually be as numerous as the number of clients already being served by AUM advisors!

Blue Ocean Strategy For Financial Planning

In 2005, business professors and authors W. Chan Kim and Renee Mauborgne published a book called “Blue Ocean Strategy”, in which they described the business landscape as being divided into Red Oceans and Blue Oceans. Red ocean companies were those that competed in a known market space, against established competitors, and engage in the cutthroat tit-for-tit competition that continues until one business wins and the other business dies (and the other is bloody-red from the war they are fighting against each other). In this context, using a retainer fee model to compete against AUM fees is a red ocean strategy, and one that – for all the reasons mentioned here – is unlikely to be victorious for the retainer fee model.

In 2005, business professors and authors W. Chan Kim and Renee Mauborgne published a book called “Blue Ocean Strategy”, in which they described the business landscape as being divided into Red Oceans and Blue Oceans. Red ocean companies were those that competed in a known market space, against established competitors, and engage in the cutthroat tit-for-tit competition that continues until one business wins and the other business dies (and the other is bloody-red from the war they are fighting against each other). In this context, using a retainer fee model to compete against AUM fees is a red ocean strategy, and one that – for all the reasons mentioned here – is unlikely to be victorious for the retainer fee model.

However, the other companies of the book are defined as “blue ocean” companies, those that enter a new and previously unknown/untapped marketplace, and one that is untainted by competition. In a blue ocean marketplace, there is potential for incredibly rapid and nearly unfettered growth, because the red-ocean tit-for-tat competitive battles simply don’t exist, because there is no competition. In fact, that’s the whole point of blue ocean companies – they don’t pursue their business models in known spaces against established competitors, but in untapped marketplaces where there is no competition. And in this context, as illustrated, there’s a tremendous opportunity for retainer fees – not to compete where AUM fees are, but to compete where AUM fees are not.

In fact, given that the overwhelming majority (as much as 80%?) of households today cannot possibly be served by AUM fees, ultimately the market potential for retainer fee models (along with the hourly fee model, although it has some business caveats too, due to high fee saliency) may be so large that, in the long run, retainer fees may become the dominant model, and AUM fees becomes a niche model for higher net worth clientele who happen to have assets to manage, in addition to needing financial planning services! In turn, the tremendous blue ocean potential of non-AUM models helps to explain the growth of non-AUM-centric turnkey financial planning platforms (TFPP) in the past decade, from the Garrett Planning Network to the Alliance of Comprehensive Planners to XY Planning Network. After all, advisors competing in that space enjoy both a huge untapped market, and almost no competition, because the rest of the industry is still pushing towards operating under the ever-more-crowded-and-undifferentiated AUM model!

Notably, in the long run retainer fee models – even or especially operating in market segments that require a higher volume of clients who generate less revenue per client – will still need to figure out how to manage some of their business challenges. Fee sensitivity will be an issue, although breaking down an annual retainer fee into a monthly retainer fee, and automating the billing process (via credit card or ACH bank transfers) may help. Scaling a retainer fee model will be challenging as well, in light of the fact that finding economies of scale in any advisory firm business model has been difficult, and it's only more challenging when staff expect annual raises (in the midst of an industry talent shortage) even as clients push back on fee increases. Although automatic escalation clauses (that automatically increase the monthly or annual retainer every year) or tying the fee to total income and net worth (e.g., 1% of income plus 0.5% of net worth) may help. A standardized process of billing with standardized pricing and automatic escalations will also help improve the long-term valuation and potential to sell a retainer-fee business in the future.

Nonetheless, even with some standardization of process and inflation-adjusting retainer fees, the profit squeeze of rising staff costs amidst slow retainer fee growth may remain a problem for “large” retainer fee firms, even as it will probably be less of an issue for small advisory firms or solo practitioners (which tend to have far less overhead and staffing costs in the first place). On the other hand, the smaller firms that are less sensitive to economies-of-scale issues may be the ones to struggle most with the need for a higher volume of clients to reach a critical mass of clients in the first place (as larger advisory firms at least have the size to scale their marketing, while smaller firms often do not). Though here again, centralized TFPP (Turnkey Financial Planning Platform) solutions that help market for their particular niche/style of advisors can help.

Notwithstanding the growing pains that the retainer fee model may still have to navigate in the future, though, the bottom line is simply this: advisors who are considering a retainer fee probably shouldn’t do it as a strategy to differentiate from (and compete against) AUM firms, given the challenges retainer fees will have competing with AUM firms for AUM-eligible clients. Firms that are feeling pressured about their AUM fees, and/or challenged by robo-advisors, need to focus on improving the value proposition of their AUM-fee firm (e.g., by focusing into a niche, deepening their financial planning services, etc.), not using a retainer fee as a differentiator (competing on price is a race to the bottom!). Instead, pursue retainer fees as an opportunity to bring financial planning to those who have a financial means to pay for advice (e.g., from cash flow) but not the available assets that so many AUM-centric firms require. In other words, the opportunity for retainer fees is not to compete in the bloody-red ocean of AUM firms, but to sail into a new blue ocean for untapped and undeserved households instead!

So what do you think? Are you considering the switch from AUM to retainer fees? Have you already made the change? How have your clients reacted to the retainer fee model? Have you been able to raise your fees over time to keep up with the rising costs of running an advisory business?

When I was an hourly planner, the biggest issue I saw was price saliency. It took someone who knew that they wanted financial planning and objectively *and* subjectively understood the pricing to go for a planner with an hourly model.

Therefore, while the blue ocean may represent the biggest opportunity, the retainer and hourly models also represent the biggest challenge to swimming in that blue ocean.

I like the idea of packages of financial planning because that helps codify what the client/customer will receive for what they’re paying. Financial planning, to most, is somewhat nebulous – we answer the “what” and sometimes the “how” for those who are bought into the “why” – but that’s sometimes difficult for a potential client to grasp and translate value into price paid.

However, if I think about analogous professions, attorneys and accountants, when they appeal to those blue oceans, they’re offering packages. Think about Nolo, H&R Block and divorce attorneys. They offer specific packages, from a will kit to tax returns to a no-contest divorce for set prices.

Furthermore, these packages revolve around life events. Usually, people don’t think about wills unless they have a kid or a loved one passes away. April 15th comes around every year.

The same can be said to hold true for financial planning. In the blue ocean, there are still plenty of events which can trigger the desire to have questions answered – a payraise (or layoff), a newborn, a better job offer, etc.

A planner who offers packages and who can either a) nail SEO for those events, or b) can get the word out and be associated with those events has the opportunity to get in the door with those clients and grow a relationship over time.

For example, if a couple finds out that they are pregnant with their first child, that may trigger questions that can be answered by packages, such as:

* How much do I need to save to put my child through college, or

* Do I have enough insurance?

Planners can offer those packages and build the relationship. After delivering value for a reasonable price, they’ve lowered the barrier to entry for further planning relationships.

Answering specific questions resolves pain points for potential clients, removes ambiguity in the clients’ mind about what they’ll get for that price, and increases trust for future relationships. It may also be the entry point to another financial model for those clients later down the road.

Jason,

Indeed, I’m a huge fan of the idea of building modular parts of a plan up towards a whole. See https://www.kitces.com/blog/modular-vs-comprehensive-financial-plans-are-the-parts-worth-more-than-the-whole/ for some writing on this I did a ways back.

My gut is that building from modular planning into a whole will likely be more and more popular in the future, and put pressure on those planners who push for a big upfront fee for a big upfront plan that the clients weren’t actually asking for anyway…

– Michael

When I started my firm in 2011, I reviewed all of the pricing models exhaustively, and I settled on using an annual retainer fee, billed quarterly out of an investment account.

Michael, you hit on most of the points I usually make – from the elimination of conflicts surrounding mortgage payoff and guaranteed income via SPIAs, to the ability to charge based on complexity and value instead of account size, and the revenue stability for my firm.

It’s nice that the flat retainer model is a differentiator right now, and I can usually come in much lower in price to my AUM competitors in my market ($500k-$5M, heading into retirement and in retirement), but it’s not my primary reason.

I have designed my firm to stay small and be a “lifestyle practice” – I don’t aspire to run a huge firm with a lot of staff. Thus, overhead is minimal, I have 30+ years left (I’m 41) to worry about firm value, and scaling the firm is unimportant.

Yes, my fees may grow more slowly over time (even thought I have not seen push back on reasonable increases because it’s not hard to demonstrate my value above and beyond my fee), but that’s a trade-off I’m willing to make.

I’m a conservative planner for my clients and myself – I like reasonable certainty (especially after living in the chaotic world of commissions and AUM fees my first 7 years – never once could I correctly guess how much a paycheck would be), clear messaging, and a good story to tell clients and potential clients.

-Elliott Weir

Elliott,

Certainly with a goal of running a lifestyle practice, I see far less risk in a retainer model from a practical perspective. Clients tend to be sticky, personal lifestyle costs will (hopefully!?) grow slowly (as opposed to staff advisor costs, which grow more quickly!), and an individual advisor has some flexibility to change and adapt.

But I have to admit that in the end, differentiating primarily on price continues to be a risky business strategy. As the robo-advisors themselves are learning, having gone to market with a commodity that they priced lower than their competition, and now are suffering from competitors (e.g., Schwab) who lowered their own prices further in response, and simply rely on cross-subsidy from other profitable services to make up the difference while disrupting those who competed on price alone…

– Michael

I agree that differentiating only on price is not how I want to go. But as you illustrated, if a different adviser is charging 1.25% AUM fee for mutual funds with 0.75% average expense ratio (for $40k/year on $2M) , then my 0.1% ETF portfolio + my fee can come in at 1/3 the cost!

I work for a firm and I am the youngest planner in the firm. We use an AUM model, and I have been proposing that we add a retainer-type model in addition to AUM. With the idea being that we can work with those who don’t have much in the way of investible assets on the retainer model, develop a relationship, and when it makes sense to go to an AUM model when they have accumulated more investible assets, make that switch.

Now, we don’t have account minimums, but rather a minimum annual fee that is charged if the AUM fee generates under a certain amount (i.e. if they have less than a certain level of assets invested with us it essentially means that they would pay the minimum fee rather than the fee that would be charged based on the AUM rate), so we already have the ability to “take a chance” on working with someone who might not have a lot of investible assets at the moment, but could legitimately become a great client in the future.

So from that standpoint, I’m not even sure that we need to add a retainer-type fee into the mix. However, my thought was more from a marketing point of view with the younger generations being “accustomed” to paying for things on a monthly or quarterly basis (e.g. cell service, streaming music, Netflix, etc.), and creating an option for them that might align better, at least at the beginning, with what they prefer from that point of view.

I have no problem as a planner reducing my AUM for clients to pay off their house, or any other action that might reduce AUM in the short-term (to me that is the most glaring conflict of interest that comes up with the AUM model), as long as it does make sense for them and is in their best interest. In fact, a client just took out about 6.5% of their portfolio with us to pay off their house, and it was perfectly fine with us because even though that decreases our AUM on that client, it is best for them in the short and long-run, and I truly believe that if you do what is best for your clients, everything else will take care of itself.

At this point, I’m not sure what will come of my “proposal” simply because of the negatives you point out about the retainer model, and the way our fee structure is set up (such that there is a minimum fee, as opposed to a minimum asset requirement), I’m not sure a retainer is truly necessary. The one thing I do know is that they won’t be relaxing the AUM model with the retainer model. But, all of this is something that I have personally thought about with all the discussion of the “retainer” model coming on the scene over the last several years. That being said, I suspect the AUM isn’t going anywhere any time soon.

AUM are a conflict and the good advisers know that the way they are charging is not aligned to where their value lies. Letting go of all the conflicts it creates in client best interest i will make one point; It is not our money, it is the clients money. Why should we be able to charge a percentage on their wealth for not “really” being in control of how it grows. If an Adviser makes a call on the markets to make it grow faster than the index, what is that? a risk. Is it a risk we take on or the client takes on? The client does. To justify this risk and the advisers fee, the investments must i argue out perform by at least 2% over the index return. Not many i know do consistently and long term! Investment advisers are making calls and risking clients money to justify their fee. I argue a lot of advisers do more damage than good in his space. We provide a service and for that service the client should pay a fair fee. Personally, it’s not about what model is better for the “firm”, it’s what model is better for the client.

Chris,

I would disagree a bit with your final statement, inasmuch as a model that isn’t viable for a firm in the long run isn’t better for the client either. Clients are not well served when advisory firms must lay off staff, lose key advisors who cannot grow with the firm, and lack a continuity plan because no one will buy/continue a firm that isn’t run profitably and successfully in the first place.

Granted, I’m certainly not advocating that advisory firms need to make 50% profit margins (not that any do anyway), but running a firm in a manner that requires constantly firing or turning over staff, has an inability to grow, or can only succeed by pursuing wealthier and wealthier clients who can pay bigger and bigger retainers to replace existing “smaller” clients from prior years isn’t great for clients either?

Respectfully,

– Michael

While I agree profitable business is the goal here.

But doesn’t AUM fees encourage advisers to pursue the ones who pay them more and neglect clients who do not IE: not much wealth. It’s more important for them not to lose the bigger balances and hope the smaller balances stay on board. If they lose a $100,000 client it’s 10% of the impact as a $1,000,000 client.

Most firms worry about their sale value, as one day they want to sell and most owners of advice businesses are in their 50s and 60s. The sale value is paid as a multiple of ongoing revenue, not based on happy engaged fee paying clients. The goal is simply to grow ongoing revenue.

This tie creates a conflict and the adviser is incentivised to dial up the ongoing revenue and take on as many clients as they can. Rather than focus on client happiness and satisfaction. It’s short term mindset with a pay off on the horizon.

Profitable businesses are ones who have a steady stream of new clients and keep their clients happy long term. It’s not rocket science.

Most unprofitable businesses have high staff and client turnover of higher net worth clients, have too many support staff doing inefficient jobs, are poor at attracting suitable new clients and are finally running ridiculous processes that waste a lot of time.

You can run a profitable business on flat fees for all ages.

%’s are what fund mangers get away with using, not what strategic advisers should.

Michael, as usual, very well-written.

In Australia, for a host of different reasons, we have some interesting insights into the AUM v Retainer model. I’d like to challenge you on some of your conclusions.

Firstly we have a very sophisticated industry and government pension marketplace that have been ‘fighting’ for Australian’s compulsory pension monies for years on our TV screens with a ‘compare the fees’ advertising campaign. It’s raised awareness of AUM fees significantly among all Australians.

We always ‘enjoyed’ a very vigilant consumer-first (heavily subsidised health care, compulsory employer-sponsored pensions, with welfare being the greatest sector for our taxes), we’ve a relatively small population (compared to your country!) with aggressive ‘financial planning’ competition (only four major banks all in the top ten companies of Australia by revenue) and a government keen on more regulation/legislation for a slowly maturing financial services sector (for instance it’s law to ensure client’s opt-in every two years)

Australians are slowly realising the ‘value’ of doing business with a ‘professional’ – i.e. someone that does everything from the perspective of putting the consumer first. AUM fees don’t naturally do that.

Australians are slowly understanding what a ‘basis point’ charge is (i.e. they are slowly talking more about 100 basis points version 1% – not only does it sound more, it is more).

So, how have advisory firm’s here evolved in these circumstances?

The ones I work with are transforming from AUM-based to retainers (not hourly rates).

They are introduced ‘access fees’ for the ‘comprehensive’ offering and increasing dropping their ‘transactional advice’ unless they can command a premium. Their access fees rise with demand. They use ‘fee tension’ (i.e. pricing to win only 66% of new business and retain 80% of on-going) to ensure they are winning retainers that are profitable as they are pricing to grow not pricing to win. They are expanding their offerings beyond classic financial planning, investment, insurance, tax to project management, client and strategic management. They are outsourcing ‘core’ functionality to cheaper labour countries north of us with excellent training and skills. They are experiencing 40% uplift in fees from active clients every year whose lives have clear complexity (usually too busy) and still unmet aspirations which neatly offsets any ‘drop’ in on-going work. They aim to make 40% net profit before taxes.

They don’t use terms like high-net-worth (as that’s a product segmentation category) but rather categorise on the complexities their different client sets face.

Everyone is different. Our markets are different to yours. Our circumstances are unique to us.

However, better business skills are required than in the past. It’s a work in progress and excellent pieces like yours very much help the debate

Jim Stackpool

Over time, both types of fees will converge to essentially the same price point so that the silly and unprofessional marketing claims made by the retainer fee zealots will disappear. The robo’s have already won the race to the bottom so eventually the ceiling will be established. My guess will probably be around 1/2 of 1%. At this price point the retainer model has no cost advantage and the aggressive firms will start poaching the smaller clients who are being gouged by the retainer model. We can all agree that the traditional 1% money management firms with bloated cost structures are walking dead. If you are not running lean and mean, regardless of firm size, it is going to be painful. Before we get all full of ourselves and our genius and uniqueness in establishing great financial plans, technology is not going to stop at the border of portfolio management. It is coming for the human financial planner as well. The moat is not wide, despite our belief.

So by your argument, 50bps is the max an adviser could charge for everything they do beyond investment portfolio management. For a $2M client, that’s $10k/year. You don’t think that I could help a $2M client and be profitable at that price point?

Not if a firm’s AUM fee for accounts above $2M are 25 bps. See how this game is going to play out? It is simply a chess game of language and marketing. Eventually all the price points will converge whereby there is no discernible price discrimination, REGARDLESS of the language used to describe the fee. This is the way the financial services and Wall St. have always worked particularly since Chuck Schwab blew a hole in brokerage commissions.

You chose $2M for a reason as opposed to $500K or $1M, because that is the marketing narrative of the retainer model firms. Anchor on the 1% and use a large account size to emphasize on the “fee differential.” There is nothing new here. Cheaper trading commissions, no-load mutual funds, low fee index funds, low fee ETF’s, free stock trades for opening an account, and of course now free robo’s. AUM firms will go three ways. The “dinosaurs” will wither away or survive based on client ignorance. The “high visibility firms” will flip a big middle finger to the low fee competition because they know there is a client base that will pay anything to be associated with them and they will pull a few marketing stunts (cough, cough, fee rebates) to throw the clients a bone or two because they know media peers won’t dare challenge them. Finally, there will be the rest of the AUM firms that will under no circumstances be undercut and let clients walk out the door.

You enjoy being quite combative, don’t you BA31? My pricing is neither “silly” or “unprofessional”, nor am I a “zealot”. I’m simply a business owner who has priced his offering a certain way and believe it works for my clients and me.

I’m not pricing to be the cheapest, and if AUM-based advisers continue to lower their fees, it does not affect me. My clients understand exactly what they pay me (something few people seem to understand), and what the value is of my expertise, time, and the impact to their financial future. The price I deem as fair to me and my clients just happens to be less than what I see AUM advisers charging.

I’d like your opinion. Assuming I stay with a flat retainer model, in your mind what would be a non-silly, professional way to market my firm?

Interesting article, but way too much focus on looking after the interests of the advisory firm and not the actual clients who pay the fees.

Why should fees escalate at the same rate as capital market returns? Firms expenses such as staff costs, premises etc are not linked to the stock market. A fair rate of escalation taking into account rising costs would be acceptable to most clients as its they way other industries manage rising costs.

Why so concerned about having an honest conversation about fees and the value provided each year? To use AUM as a model because it avoids having to have that discussion is an admission that there is a very weak value proposition – why not fix that, make it invaluable to your client and happy to pay, rather than obfuscate and avoid the subject.

Ultimately charging ad valorem fees based on a client’s wealth is not the way the leading professional services operate – can you imagine a heart surgeon asking what the value of your house and portfolio was in order to quote you his fee? The most respected professions (so ignore real estate agents etc) simply calculate the cost of delivery of the service, their level of expertise, risk, complexity and value – and add their acceptable profit margin to arrive at the fee they will charge.

Wealthy investors are getting wise to the deep conflicts of interest inherent in the AUM model and have begun to vote with their feet..

Alan,

Given the dominant rise of the RIA with its AUM-based model in the US, which is taking market share from every other segment of the industry right now, the only “investors voting with their feet” phenomenon here is TOWARDS the AUM model.

Granted, that could change someday, as consumer preferences do from time to time. But there is ZERO evidence of ANY substantive feet-voting away from AUM at this point, at least in the hyper-competitive US space. Instead, it’s the AUM firms that are growing larger the fastest, reinvesting the most into services for their clients, and ACCELERATING their growth pace…

– Michael

What if fee saliency is good for our clients and the industry? Sometimes paying a fee is motivating – motivating for the client to “get their money’s worth” and motivating for the advisor to add value > cost.

Why do we (AUM advisors) deserve a market based raise every year? Why do we charge 1%? Is “because people will pay it” acceptable?

In full disclosure, I have charged now under all available methods… Currently 80% monthly retainer and remainder AUM and hourly. I left commission world to reduce conflicts in my advice delivery. My AUM portion of my business still feels like the old commission business – it doesn’t jive with advice.

Daniel,

I think this is the fundamental tension in any business context. From a pure consumerist perspective, the highest fee saliency makes for the most discerning customers. HOWEVER, that only works best in a world where clients are entirely rational. Which isn’t the case.

As a result, we see problems like “people won’t get an annual check-up simply because the insurance company requires a $10 co-pay”, a grossly inferior financial (and health) decision that is swayed by making a fee salient (and that’s still a tiny fee relative to the actual cost of the service!).

The challenge is finding the balance in a world where consumers are NOT rational and do NOT always behave rationally in response to a salient fee, while designing a model that can serve those clients well and not take advantage of them either.

– Michael

So charge a person an account-based fee which is auto-deducted from their account and is greater than $10 in order to punish them for being “irrational”?

It seems regulators balk at the idea of retainers — wanting a more transactional business (fee for plan delivery) or a specific hourly billing rate for services actually rendered. In discussing this idea with my current B/D and with a compliance company in forming my RIA, both cited concerns and suggested I table the idea, at least until after my RIA has been approved. Until the regulators accept the retainer model as “normal business,” I fear that it will be difficult to build momentum on the concept. Any thoughts on how to present the retainer model so as to ease the minds of the regulators?

Matt, when I formed my firm in 2011 the regulators (State of Texas) didn’t have any problems with the retainer model. In my experience, it’s the B/D world that has a harder time with it, which is one (of MANY) reasons I left that side of the business.

The model was not presented in an special way, other than a flat agreed-upon fee for comprehensive financial planning. The folks at AdvisorAssist helped me set everything up for my firm (Client Agreement, Compliance manual, filings, lots of etc.). I was audited after my first year in business by the State of Texas and came through with flying colors!

There is a vast desert that exists between the landscape of today and the blue ocean opportunity. There is no clamor among the public to switch from AUM to retainer. Clients want reductions in AUM fees not a wholesale transformation. Even those in our industry that refer to the death of AUM model rank advisory firms by AUM. I’ve never once seen a ranking based on number of financial plans generated or hours billing. The idea that retainer fees are somehow more stable during market downturns than AUM is an unproven assumption. Where do we draw the data from to make this assumption? I can certainly understand how the retainer model makes it tough to grow revenue, but I fail to understand why clients would leave one model and not the other during tough times, especially since the AUM fee declines during downturns while the retainer fee does not.

The retainer model is attractive to industry experts who have the time and capability to understand the value distinction. The average consumer does not. Otherwise, they wouldn’t choose high commission products to begin with. Why is a retainer model inherently more fair to the client? I defy anyone to justify how they can charge essentially the same fee to every client and call it fair. Even hourly fees are subject to unfairness. Do we really know how many hours a plan will take at the outset? Clients do understand that access to technology is lowering the cost and increasing the scale for firms that utilize it properly and they expect to see fees drop as a result. As advisors, we have to take our AUM model and try to make it both fair to the client and profitable to the business and hope that we generate enough value to justify it.

In any fee arrangement, some clients will get a bargain, while others will overpay and it’s not the fault of the advisor necessarily. I think the blue ocean is filled with clients willing to pay a small AUM fee to receive investment direction AND help with other financial goals and issues. The amount that those clients are willing to pay is probably the more concerning issue than how they prefer to pay it.

James,

I agree that there is not a client-initiated clamor for retainers vs. AUM, but when I can demonstrate that I can charge them a fair fee for my time during the year AND beat the inflated costs of the typical AUM fees, then the clients are quite interested!

Assuming long-term relationships, the annual retainer model is more stable in downturns by its very nature. My compensation is level regardless of what the number of the monthly statement says. It’s not that clients leave AUM during downturns, but that the AUM calculation by its nature creates an “automatic income reduction” program.

And don’t confuse an annual retainer fee that is level to a “one price fits all” fee. I charge different clients different fees, but it’s based on the complexity of the situation and what I perceive to be the opportunities to add value.

If you are not charging “one price fits all” than you are not charging a flat fee or a retainer fee, you are instituting A La Carte pricing. Words matter. With that said, A La Carte pricing is more fair than the pure “flat fee” scheme unless you charge a significant minimum fee which harms very small clients, a fact which the retainer/flat fee crowd willfully ignores. However, this is far from superior to the AUM in terms of conflict. A la Carte pricing is no different than how mechanics price their services. It is in YOUR best interest to find complexity where it may not exist and it is in YOUR best interest to perceive opportunities to add to your bottom line. The ignorant client is at the mercy of the financial mechanic.

Attorneys charge different retainers for different types of cases, and that’s what we are talking about here. My retainer fees are flat because they are agreed-upon and do not change – that’s flat. That’s what the regulators call it, and that’s the common nomenclature. It’s not A La Carte because I don’t charge different fees for investment management, estate planning, Social Security maximization, help with Medicare, retirement income planning, etc.

I do have a minimum fee, and yes that means I cannot help everyone (nor do I try to). My practice is designed to service a particular niche that can afford my services and value the advice I offer.

And given that this entire relationship is designed to be long-term, I price at a point that I would be proud to have it published in a newspaper. I do not create complexity (I aim to simplify), but it makes no sense to charge a person who has a pension, a 401k, and some savings the same as someone who has estate planning needs, legacy needs, complex investment and tax management, insurance issues, blended families, etc.

First of all, let me apologize if it seems that I am being combative because I am not trying to be. I believe that the best fee is one that is agreed upon by the client, the firm, and the regulators.

With that said do you see how language matters? As soon as I “label” you with a term that may nor may not be accurate than you are left to defend and explain? The term flat fee or retainer fee or AUM fee is just a label, nothing more, yet they are being marketing as being wildly different both computationally and morally. It is the oldest game in pricing. Label something different and promote it as drastically lower and morally superior so that the customer must be a complete idiot not to sign up. THE ONLY thing that matters in any pricing situation is “what you get and what you pay.” That is true of any industry. In the investment/planning industry, for the client is what are their TOTAL FEES. It doesn’t matter what the regulators call it. Perhaps rather than rubber stamp it they should regulate and standardize fees in terms of language used.

Retainer firms can’t have it both ways in terms of marketing. They can’t point out the fee differential on the high end and pretend it still exists on the low end. Clients can do simple math and the AUM firms will adjust their price points to wipe out the retainer advantage.

We all think we are special and offer unique services and experiences. We are not. Everybody wants the same thing..a sustainable business with loyal clients, preferably that we like and cause us less stress. The price point is right in front of us. Robo’s are free and Vanguard is 30 bps for the Full Monty. I sure we will see the day where a client can input all of their financial info and a high quality plan will be spit out to their device for $9.99.

In fact we have already seeing the next evolution of folks trying to create a niche with planners trying to reinvent themselves as lifestyle guru’s, psychologists, and marriage experts and venturing into areas where they have little professional training.

Finally, and most importantly, we are all fiduciaries regardless of fee language and computation. The retainer fee firms are using their fee structure to attack the character of the AUM firms and questioning their fiduciary duty. This is unprofessional and borderline unethical. You don’t get to claim somebody is violating the fiduciary standard mandated by law because you think your fee structure is better. The fiduciary standard is fee agnostic. For every subtle “conflict of interest” retainer firms throw casually toss around it can easily be countered by a “conflict of interest” with a retainer firm. Eventually a large firm will take offense and their will be lawsuits involved.

AUM and retainers are different computationally but not morally, and though I have not seen any retainer-based firms drawing a fidicuary issue with AUM compensation, I would agree that statements like would be misleading.

My retainer pricing model works wonderfully in some situations and not in others. One size never will fit all (nor should it). When I started my firm I selected the retainer model instead of AUM because I saw how well it would work with my target market who have investable assets of $500k-$5M. Price is only one component of my differentiators and value proposition.

You do make a bold conclusion that because “clients can do simple math” they will automatically demand lower price points. Very few clients of mine came to me understanding the total fees they were paying (which I fault the former adviser), and these are very intelligent people. I enjoy being able to lay out the true costs they pay.

You present a dim opinion of the value of our profession. I do not compete with robo-advisers nor Vanguard’s offering, and the planning done only by software is to TurboTax as we are to CPAs. I strongly believe my clients value the explanations I provide so they can make better decisions, value the help to manage emotions, and value the ID of risks they didn’t know about. Probably most importantly, I hold them ACCOUNTABLE to themselves and get things done. Staying on a client to get their estate planning complete, their long-term care insurance applied for, or their affairs in order is not because of a simple computerized reminder system but because of a human relationship.

I would never give up my doctor for a website, my CPA for tax software, or my attorney for an automated service. That’s the value of our profession – not inputs into planning software nor asset allocation models.

Here in Australia we’ve been having similar conversations for many years.

I’m more comfortable with offering a couple of different service packages paid for via a flat fee that can be paid either from the client’s investment or direct from the client’s bank account.

To me, this aligns my ongoing service program with the services I provide and takes the focus away from asset management which is only a very small part of the value I provide.

For me, a retainer also takes away many of the conflicts of interest that can exist. If the best advice is for someone to not invest a lump sum but instead repay debt, I’m still getting a fee from the retainer. If I was using an AUM model, there’d be the temptation to get the money invested so I could begin to earn revenue from it. I know not everyone feels this conflict, but it’s there.

There’s no one ‘right’ answer to this – everyone has an opinion that’s equally valid. Importantly, our opinions don’t matter – it’s going to come down to what the client wants. As there’s more discussion on this topic in the public space, our clients (and future clients) will move to the model that they perceive to deliver the highest amount of value.

Great article as always. We charge flat fees and AUM fees, both have their pros and cons. Our clients with $20m+ in net worth tend to prefer the flat fee model. Our clients with a lesser net worth prefer AUM fees. We think offering both, keeping fees transparent, offering world class advice and service, and recapping our value add each year for each client, are what really matter. No fee structure is perfect, just ask attorneys and CPAs! But fair, transparent and competitive are all you can ask for.

Well said Rob.

If fees are transparent then the client should be allowed to decide what they want depending on value (perceived or real) they receive. Given the Best interests and other requirements of FOFA the market should be allowed to determine fees paid by clients and how they are charged. Many within industry are pushing an agenda that 1 is better than another and somehow fee structure will miraculously leads to good advice and outcomes for clients.

All fees have conflicts but if you want to be treated as professionals you need to manage these.

Fascinating discussion. Clearly, both pricing methods have pros and cons, for both the advisor and the client. One thing I haven’t seen mentioned is sequence-of-returns risk for clients in retirement who rely solely or largely on their portfolios to fund expenses. In a bear market, clients whose fees are based on AUM see the percentage withdrawn from their portfolios for fees remain constant. In contrast, those whose retainer fee stays the same regardless of market movement (and my sense is that that’s the norm) see the *percentage* withdrawal from their portfolios for fees actually go up — just when that will do the most damage!

Michael – Great article! I thoroughly enjoyed reading the article, as well as all of the comments. My question for you: Are there any good resources to understand how big the retainer fee/hourly fee planning market is, and how this is growing relative to the AUM based industry?

Thanks again,

Hussain

Over time AUM model cannot survive as index fees and commissions approach zero. Conflicts are reduced. Financial planning becomes a profession.

The current AUM/asset gathering model I don’t view as sustainable. Despite the arguments about value and attempts to justify an AUM fee, the reality is that 99% of firms simply aren’t providing enough value to justify a 30k+ annual fee. They just aren’t. And I know this is true from experience. An advisor who lands a $10M client in the AUM world has hit the lottery and will be making a 90% plus profit margin on this client. His margin is the flat fee advisors opportunity. My firms’ average revenue per client is higher than that of both of the two AUM firms I worked for prior to launching. And yet my clients on average pay about a third of what they were paying prior to hiring me. Imagine that. I make more and my clients pay less! That’s what happens when an industry chooses to price not based on cost or on value but based on an arbitrary metric like assets under management. We may be just in the very beginning stages of this, but based on what I’m seeing, consumers are starting to figure this out. HNW clients won’t pay such high fees forever when they don’t have to. AUM advisors will then be in a sticky place with lots of low asset, unprofitable clients who love the deal they are getting under AUM, while all the highly profitable high-asset clients leave for flat fees. Might take years or even decades for the transition to take place, but it will be interesting to see how this unfolds.

@Michael_Kitces:disqus what would you respond to the argument that the only reason AUM has stuck around is that consumers can’t distinguish a good advisor from a bad one, and therefore advisors have never had to compete on price? I ask because I have read a lot of ADV’s. I know some really bad advisors who charge high fees and have lots of assets under management. There seems to be no correlation at all between quality of advice and level of fees. Everyone essentially just charges 1% (with some break points) because thats what everyone else charges. And since consumers can’t comparison shop, there’s no incentive to lower the fee (in fact, lower fees might actually lead consumers to assume an advisor is inferior). In such a market, what are consumers to do? Should we just accept the status quo as “well that’s what the market will bear” or as leaders in the field should we be pushing for a higher standard that is better for consumers?

Apologies for coming so late to the party but I had prepared an article a while back, “How to Understand the Value of Your Services, Value is Based on the Costs of the Business and In the Eyes of the Beholder” that discusses HOW to price based in the manner you discuss. I have offered it to you and still do, if you would like. I believe it could be of value. Though I have not received a response I understand you get many and are busy.