Executive Summary

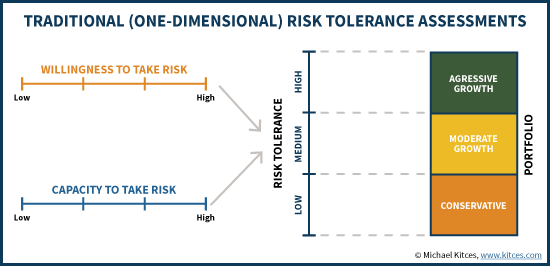

The process of assessing an investor’s risk tolerance is all about determining his/her willingness to take investment risk, and financial capacity to bear risk, and blending it together to match to an appropriate investment portfolio. Most commonly, this is done with a risk tolerance questionnaire that posits a series of questions about time horizon and need for income, and attitudes about risk and market volatility, to calculate a “risk score” and determine the portfolio that goes with it.

The caveat to this one-dimensional approach, however, is that by averaging together risk tolerance and risk capacity scores, the advisor can unwittingly end up in situations where clients with extremely low risk tolerance (or risk capacity) end up with portfolios that are far too risky for their situation. In other words, the low risk tolerance (or capacity) should have acted as a constraint to the investment policy statement, but didn’t.

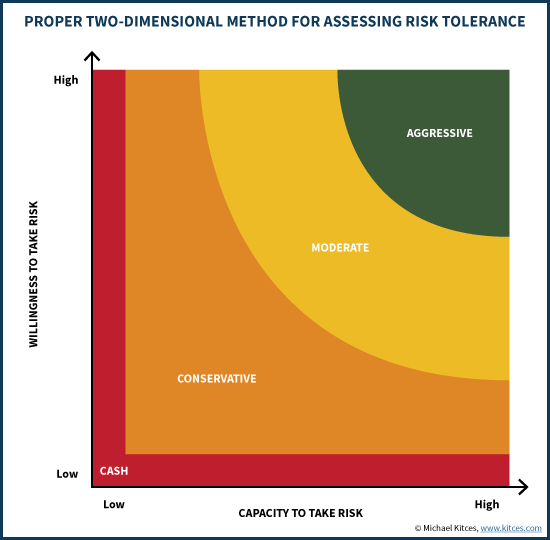

So what’s the alternative? Simply put – risk tolerance and risk capacity should be measured separately, and then scored on a two-dimensional scale that considers the contributing role (and limiting nature) of each (rather than a single continuum that merely averages the two together).

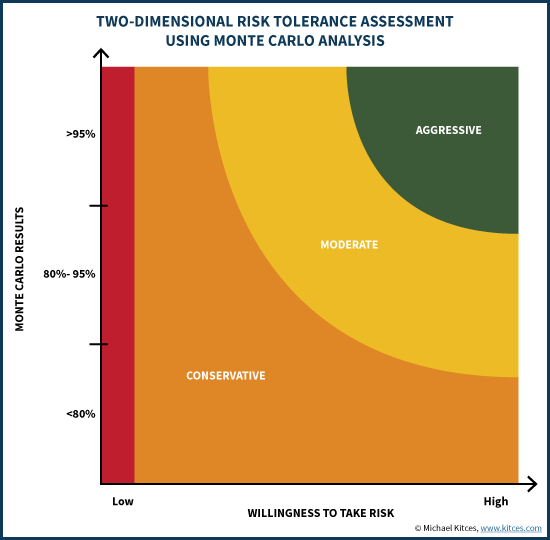

Fortunately, there are numerous risk tolerance software solutions specifically designed to assess “pure” risk tolerance on a standalone basis, including FinaMetrica and Riskalyze. And for comprehensive financial planners, the reality is that the financial plan itself is a measure of risk capacity, as reflected in the Monte Carlo probabilities of success and failure.

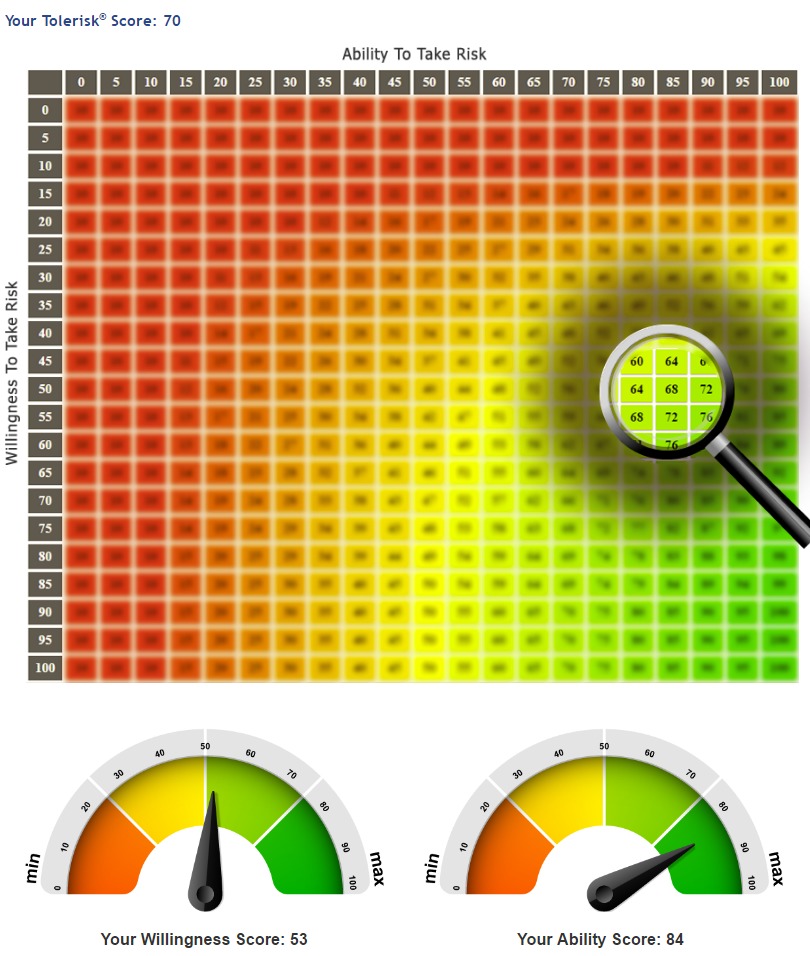

For those who don’t do full retirement planning projections for every client, a recent alternative software solution is Tolerisk, which is designed to perform a two-dimensional risk tolerance assessment by separately gathering information about the client’s risk attitudes and their basic financial goals.

The bottom line, though, is simply to recognize that risk tolerance and risk capacity are two different dimensions of the client’s overall risk profile, and must be assessed and ‘scored’ separately to properly recognize the constraining role that each can have on the appropriate investment policy statement!

Separating Risk Tolerance From Risk Capacity

The standard approach to determining risk tolerance is to ask investors a series of questions. This might include assessing their time horizon, available assets, and need for income, along with their willingness to sustain market volatility and comfort level staying invested through a market decline.

These risk tolerance questions can be grouped into two categories. The former are questions about “risk capacity” – the investor’s financial ability to have “something bad” happen in the portfolio and not ruin his/her goals (i.e., and still have time to recover). The latter, regarding willingness to take on market volatility and stay invested, assess the investor’s attitudes about risk – in essence, their true “tolerance” for market risk.

Classically, the scores from these risk capacity and tolerance questions would then be merged together into a single “score” of risk tolerance, where the investor gets a lot of “points” for a long time horizon and a willingness to tolerate a lot of market volatility, but no points if he/she isn’t willing to stay invested in a down market or has an unusually high withdrawal spending need (such that the goal would be ruined by an ill-timed bear market).

The combined final score can then be mapped to an “appropriate” portfolio and associated investment policy statement – with high scores tied to an aggressive portfolio, moderate scores tied to a moderate growth portfolio, and a low score tied to a conservative portfolio.

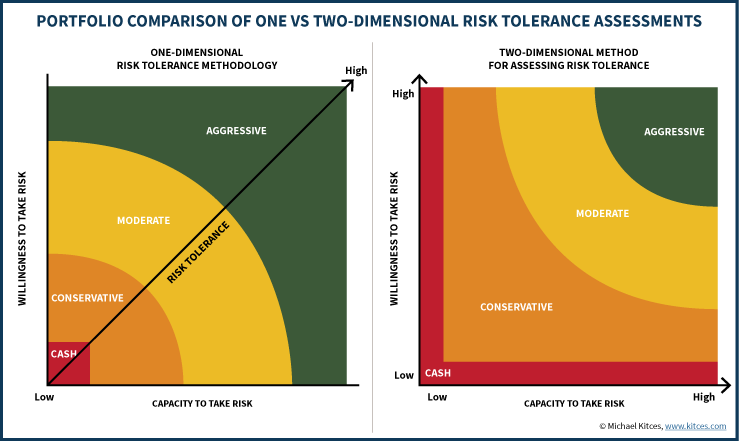

Unfortunately, though, there’s a fundamental problem with this risk tolerance questionnaire approach. The issue is that while it’s called a “risk tolerance” score, it’s really the combination of risk tolerance and risk capacity. Which both impact the appropriate investment portfolio… but blending them together into a single score ignores the unique contribution that each brings!

In particular, the “gap” that is created by the combined-tolerance-and-capacity risk score is that just because an investor can afford to take risk doesn’t necessarily mean he/she wants to or needs to. After all, having a lot of wealth or a long time horizon means the investor could take risk (and still have enough time/assets to recover), but also means he/she might not need any risk to achieve the desired goals! Similarly, an investor who has a high tolerance for risk but limited wealth might be willing to take risks, but won’t be able to achieve his/her goals if the risk event actually happens.

Unfortunately, though, when risk tolerance and capacity scores are merged together, there’s no way to spot these discrepancies!

Aligning Two-Dimensional Risk Tolerance And Risk Capacity

So given these dynamics, what’s the alternative? Simply put, it’s not to add risk tolerance and capacity scores together to a single item, but instead, to evaluate (and score) them separately.

The end result is that instead of a one-dimensional “risk tolerance” score from conservative to aggressive, the advisor ends up with a two-dimensional perspective on how to assess the appropriate portfolio.

Of course, clients who have both a high tolerance and high capacity for risk will still get an aggressive portfolio, and those who have no tolerance nor capacity for risk will be conservative (or outright in cash).

The distinction, however, is that when investors score high on one measure but low on the other, the “classic” single-score approach adds the scores (when tends to skew them to at least moderate growth portfolios), while the separate approach properly recognizes low risk tolerance (or low risk capacity) as a constraint.

In other words, if an investor has a very long time horizon but no tolerance for risk – i.e., an ultra-conservative young investor – the traditional approach would drive them into a moderate growth portfolio they can’t tolerate (just because they can “afford” to lose money and wait for it to recover), while this approach will recognize that tolerance for risk should always be a constraint. Putting a young investor into a volatile portfolio he/she truly can’t tolerate is just an inevitable lawsuit waiting to happen in the next market downturn.

Similarly, an ultra-risk-inclined investor who has no emergency savings and a near-term time horizon might get a ‘moderate growth’ portfolio with a blended score (since he/she is very tolerant of risk), but the separate approach will properly recognize that the investor simply can’t afford to take that risk.

In essence, having a low willingness to take risk, and/or limited capacity to afford risk, should be viewed not just as a component of the risk score, but a constraint to the proper portfolio the investor agrees to in an Investment Policy Statement. Which means investors who have low tolerance or low capacity should remain in conservative portfolios And similarly, investors with “just” moderate tolerance or capacity should stay in moderate portfolios, and not drift up to aggressive just because their other score is high.

Assessing Two-Dimensional Risk Tolerance And Risk Capacity (Separately)

Ultimately, the key problem of most risk tolerance questionnaires today is not that they seek to assess both risk tolerance and risk capacity; it’s simply that they evaluate the results together in a single score, rather than using each separately to determine an appropriate portfolio. Unfortunately, though, so many risk tolerance assessment tools are built this way from the start – including those produced by many compliance departments – which means in practice, “unbundling” the two may be necessary.

The good news, however, is that there actually are a number of standalone risk tolerance assessment tools out there that do look only at measuring risk attitudes and the pure “willingness” to take risk.

The longest standing pure risk tolerance assessment tool is FinaMetrica, which has a robust psychometrically designed risk tolerance questionnaire. A more recent alternative would be Riskalyze, which similarly asks investors a series of questions to understand their willingness to engage in various levels of risky investment trade-offs.

Of course, if the advisor is going to assess pure risk tolerance on a standalone basis – without mixing in risk capacity questions regarding goals and time horizons – it’s still necessary to separately evaluate risk capacity, too. On the plus side, the reality is that for those who do financial planning, the financial plan itself is a measurement of risk capacity!

For instance, if the client’s Monte Carlo probability of success for the retirement plan is at 95%+, the client has a high capacity for risk (because even a substantial market decline wouldn’t necessitate a very large adjustment to keep the goal on track). However, if the Monte Carlo results are only 80% to 95%, the plan has only a moderate capacity for risk. And if the Monte Carlo probability of success is 79% or lower, there’s a material risk that an adverse market event could impair the client’s goal, so this would be viewed as a “low” capacity for risk.

Notably, for advisors who don’t do a full financial plan for every client, it’s clearly still necessary to have some assessment process for risk capacity.

The starting point could simply be to use the ”traditional” risk tolerance questionnaires – with questions on both risk tolerance, and risk capacity – and just recognize that they need to be scored separately. In other words, don’t score the questions and add them up to a single result. Instead, score them separately, and put the results on a grid (similar to the one above) with the low/medium/high scores for each, to ensure the actual portfolio the client gets is matched appropriately.

Fortunately, new risk assessment tools are beginning to emerge that help to accomplish this. For instance, Tolerisk measures the client’s willingness to take risk with a ‘standard’ kind of risk tolerance questionnaire. But the software also separately assesses the client’s financial ability to take risk, by gathering “basic” financial planning information to project the client’s anticipated withdrawal/spending needs over the next 20 years, and then using a proprietary algorithm to “score” those withdrawal/spending goals as a form of risk capacity. The end result of the software is a matrix of recommended portfolios at the intersection of willingness (tolerance) and ability (capacity) to take risk.

The bottom line, though, is simply this: beware using risk tolerance assessment tools that blend together the results of measuring risk tolerance and risk capacity into a single score/result. Instead, the two need to be measured separately and only then blended back together in a two-dimensional assessment where they operate as constraints to a portfolio – not a cumulative score to invest as aggressively as possible (a challenging bias of investment-management-based financial advisors)!

So what do you think? Do we need more than a one-dimensional assessment of risk tolerance? How do you separate risk tolerance from risk capacity when determining an appropriate asset allocation? Is the current software available sufficient for evaluating risk tolerance? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!

Good article. One thing that’s bugged me about the risk tolerance analysis, is that it sometimes works at cross purposes with the client’s investment goals. Risk and return are correlated – sometimes (most of the time) you NEED risk to accomplish your financial goals.

I’m sure everyone has had the client who is afraid of the slightest drop in the market, and would rather stuff their cash under the mattress (or buy gold). That “risk averse” client is actually exposing themselves to more risk over the long haul. Your Monte Carlo score takes a stab at it, but, sometimes runs in the opposite direction. Increasing allocations to risky assets can often (but not always) increase the so-called “risk capacity,” because it increases long-term expected returns.

To boil it down – even the most sophisticated 2, 3, and 4-dimensional risk tolerance analyses can result in circular discussions:

Advisor: What is your risk tolerance?

Client: Low

Advisor: Based on our sophisticated analysis, the portfolio that matches your risk tolerance gives you a 5% chance of hitting your financial goals because its invested in 90% short-term treasuries.

Client: I guess I’m “medium” then.

Michael, great job. Of course I would agree with you since your two dimensional diagram looks very much like the one we have used for nearly 10 years. (I developed it after having read Gallup’s book, Human Sigma.) You have helped me here because I have used the word “blended” in describing the approach — when in fact, we have done exactly what you have proposed here in separating the two. I will rethink my description. Please consider undertaking a deeper comparison of the tolerance tools: Finametrica, Riskalyze, and the tolerance part of Tolerisk? I know that Riskalyze asks the question in terms of “devastating” losses while Finametrica asks about beginning to be “uncomfortable.”

Our firm uses a two by two matrix; on one side is internal vs external and the other side is loss (or fear) vs gain (or greed). Your external/loss component is your objective capacity for loss, external/gain is, as pointed out in Doug’s post, the risk you need to take to meet a set of return goals. Internal/loss is your risk tolerance (the risks you will take if you must) and internal/gain is your risk preference (the risks you are comfortable with). Risk tolerance is always equal or greater than risk preference.

Under this model, the lesser of risk tolerance or risk capacity is the absolute ceiling. If your risk (and associated return) need is larger, something else needs to move: spending/savings mix or years to retirement. If risk preference is larger than your need and smaller than your capacity, you’re in a position to take as much risk as you prefer and reach for those aspirational goals.

It should be noted these measures are not fixed and much of what a planner does is move the internal levels through education and the external numbers through decisions like securing insurance, taking a pension instead of lump sum if it makes sense, getting an income annuity, etc. Often removing risk on part of the portfolio allows a greater capacity on the part that is left.

extending the dimensionality of client objectives is important.

At Gravity we created the Gsphere platform to break out many portfolio attributes

Return

Stability

Capital Preservation

Market Exposure

Income

Tax Minimization

The investors preferences for one objective more than another combine to create their customized and optimized portfolio!

This also serves to take out some of the ambiguity of risk conversations. Are risk and return positively related or not? What is risk? Skip the headache and give the client what they want.

We feel this is a good complement to the behavioral approach such as Finametrica

Great article! I agree a lot with Doug comment re “circular discussion” and “need for risk” in many situations as well as John’s regarding securing insured income streams to allow for higher risk for the invested assets. What are thoughts on client’s changing view of risk tolerance in response to market conditions (emotion)? Should we be assessing risk continually (ie quarterly)?

Great article but I have a question about age and how it factors into your Monte Carlo = risk capacity assumptions. Your table makes sense for someone at or near retirement, but what about a 27 year old, for example? She may have a lower Monte Carlo due to age, but does this mean she has less risk capacity? Maybe not?

Very good article. We have always encouraged the advisors using Financial DNA (www.financialdna.com) to separately address and measure the risk tolerance from the risk capacity, and also the risk needed to achieve the clients goals. The art is then how those key information pieces are used to build the financial plan and portfolio.

One of the key points that gets missed in these conversations is understanding the clients long term risk tolerance levels versus their short term attitudes, perceptions and desires. This is why in developing Financial DNA we have sought to specifically measure first for the long term behavior as this is the platform for building a long term portfolio. One of the problems with alot of the risk profiling tools (in addition to what Michael mentioned) is that they really only measure short term situational behavior. That is the case by the very design of the questions they ask which are highly situational in nature (and often not understandable). It is good Michael is advocating breaking the “risk profile” down between tolerance and capacity. In fact, there are more elements than a single number for risk tolerance when you get deeper into it.

Warren Buffett said “risk is not knowing what you are doing.” I think the more we can help clients “know what they are doing” in terms of investing, the less risky they will feel.

Would you say that it then is 3 dimensional analysis if we blend need, ability and willingness to take risk? In my experience, the need to take risk was the most overlooked dimension.

Unfortunately risk tolerance is a function of the old mean/variance framework. Peter Fishburn(John von Neumann Theory Prize recipient )refutes the assumption that risk is a function of standard deviation, a measure of volatility. Standard deviation implies investors are just as happy with bad outcomes as they are with good. Fishburn introduces a new measure to determine the appropriate investment strategy for each investor. He describes this as the MAR ( minimal acceptable return), the return needed to accomplish an investors financial goal. Using Fishburn’s MAR, Sortino (Sortino Ratio) created a new ratio to analyze the prospects of both active and passive managers to achieve each investor’s MAR. Sortino refers to it as the Upside Potential Ratio. The bottom line is that risk is NOT volatility, risk is not achieving the MAR needed to reach an investor’s financial goal

I really like the two-dimensional risk model separating risk tolerance and risk capacity. It provides a much clearer framework for aligning investment strategies with individual needs. I plan to use this approach in helping clients better understand and manage their financial decisions. Thanks for sharing!