Executive Summary

One of the many changes made by the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 was the repeal of miscellaneous itemized deductions through 2025… which was especially concerning to many financial advisors, as it included the elimination of the deduction for investment advisory fees! Of course, the reality is that not all taxpayers were eligible to claim a deduction for advisory fees in the first place, as not only did it require the taxpayer to itemize and exceed 2% of the taxpayer’s AGI along with other miscellaneous itemized deductions… but even then, could be lost to the alternative minimum tax (AMT). Still, though, many clients of advisors have been impacted by the loss of the deduction for advisory fees… and are now looking for any opportunity they can find to reduce the repeal’s impact and still get at least some tax benefit for advisory fees paid.

One “simple” way to help clients retain the pre-tax nature of advisory fees is to find a bona fide way to continue deducting the expenses. For instance, although advisory fees are no longer deductible as miscellaneous itemized deductions, ordinary and necessary expenses of a business continue to be deductible under IRC Section 162. Thus, for clients who are small business owners, a portion of the total advisory fee may be deductible as a business expense, at least to the extent that business-related advice (i.e., succession planning, retirement plan services, business-related tax strategies, etc.) has been provided. Though notably, only payments made from taxable accounts (i.e., not retirement accounts) could potentially qualify for this treatment, and deducting advisory fees from the business may be even more complex for those who are not sole proprietors, and must logistically manage to pay the advisory fee (or a portion thereof) from a business account and not the owner’s individual investment account.

Another way that advisors can help clients mitigate the impact of the loss of the deduction for advisory fees is to help clients pay fees from the most efficient source. As fortunately, AUM-style investment advisory fees for a client’s retirement account (i.e., a traditional IRA or a Roth IRA) can actually be “pulled” directly from the applicable retirement account, allowing the expense to continue to be paid with pre-tax dollars (at least when pulled from a pre-tax retirement account in the first place).

Hybrid advisors (i.e., those with both an RIA and broker/dealer affiliation) may also wish to reevaluate when it is in a client’s best interest to have them pay for the advisor’s services with advisory fees, as opposed to commissions. As ironically, while the financial “advice” industry has steadily been moving away from commissions and towards fees, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act gives a distinct tax preference paying advisors via commissions over fees! Because, while commissions are not deductible, per se, they can add to the cost basis of a position (such as a commission paid for the purchase of an individual security), reduce the proceeds of a sale (such as a commission paid for the sale of an individual security), or reduce the amount of taxable income produced by an investment (such as the 12b-1 fee commission paid by mutual funds) before the income is, in turn, passed through to the investor. All of which are more tax-efficient means of compensating a financial professional than advisory fees.

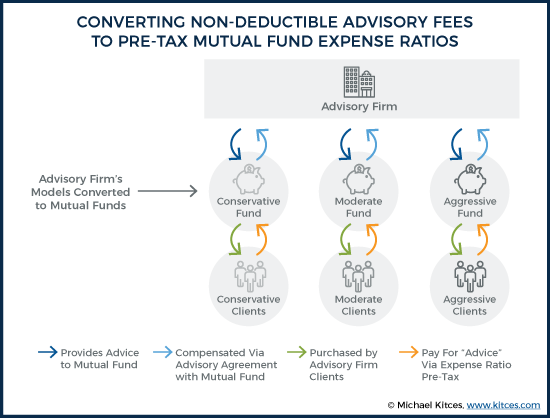

And when it comes to standalone RIAs, while they cannot receive commissions for the sale of securities (to get pre-tax treatment for their clients), RIAs may still benefit from the use of mutual funds or ETFs, by turning their investment models into such funds. By doing so, RIAs can bill their advisory fees as a management fee to the fund itself, which means clients effectively pay the RIA’s fee via the mutual fund/ETF’s expense ratio on a pre-tax basis. Unfortunately, though, the creation and maintenance of a mutual fund or ETF - and potentially multiple funds for multiple advisor model portfolios – can add a significant level of operational overhead to a firm. And even for larger firms that may be able to absorb such costs, there are still other issues to contend with, including up-ending the firm’s entire business model, and the fact that packaged funds, when held in taxable accounts, are generally not as tax-efficient as separately-managed accounts holding identical positions (from a tax loss harvesting perspective).

Alternatively, some advisory firms may look to limited partnerships as another potential method of mitigating the loss of the deduction for advisory fees, by again trying to claim the RIA’s fees as a “management fee” for the business, rather than a pass-through expense of the investment partnership. Though whether or not such a partnership would qualify as a true business – as opposed to an investment – would be of the utmost importance (as absent business status, expenses of the partnership would again be deemed non-deductible personal investment expenses), and is, unfortunately, a very grey area. A clearer path would be for advisory firms to instead opt to be compensated via a “carried interest” as a general partner, which is effectively treated on a pre-tax basis for the client… except even in the best of circumstances, such partnerships would likely be operated as private securities (limiting their availability to primarily high-net-worth and other accredited investors), and by definition, a carried interest payment is a performance-based fee (that most advisory firms wouldn’t want to operate by in the first place?).

The bottom line, though, is that while the loss of the deduction for investment advisory fees may be painful for many, there are still at least some ways that financial advisors and institutions can help their clients pay investment related expenses in a tax-efficient (pre-tax) manner!

In December 2017, Congress passed into law the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, which brought with it the most significant changes to the Internal Revenue Code since 1986. For some taxpayers, especially those who are not small business owners, one of the benefits of those changes is a simplified tax return for 2018 and the coming years. Thanks to both a near-doubling of the standard deduction and the (temporary) repeal of many other deductions, more taxpayers than ever are filing returns using the standard deduction… at least for their Federal income tax returns.

The flip side of that coin, of course, is that many of the deductions taxpayers have enjoyed in previous years are no longer available. Notably, Section 11045 of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act states, in part, that “no miscellaneous itemized deductions shall be allowed for any taxable year beginning after December 31, 2017, and before January 1, 2026.” Thus, taxpayers are no longer able to deduct expenses such as tax preparation expenses, unreimbursed business expenses and, of particular importance to both investors and financial advisors, IRC Section 212 “expenses for the production of income”… which includes investment advisory fees.

Of course, not all taxpayers were able to deduct investment advisory fees and other such expenses previously, even when they were “deductible.” As miscellaneous itemized deductions, for instance, advisory fees were only deductible to the extent that they, along with all of an individual’s other miscellaneous itemized deductions, exceeded 2% of their adjusted gross income (AGI). And even then, the deduction could be lost in part or in full if the client was exposed to the alternative minimum tax (AMT)!

Nevertheless, a substantial number of individuals were previously able to claim the deduction, and as a result of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, they are no longer able to do so. And many of those people may only be finding that out now, this tax season, as they meet with their tax professionals and get the news that so many have received this year… “I’m sorry, but your tax refund isn’t going to be nearly as big as you thought this year.”

There is, of course, nothing that advisors can to do bring back the deduction for advisory fees (or to reverse any other changes made by Congress), but that said, there are still a number of ways in which advisors can potentially minimize its impact and still preserve at least part of the pre-tax treatment for investment advisory fees.

Deduct Business-Related Advisory Fees As Business Expenses

Without a doubt, the easiest way for financial advisors to help clients preserve the tax benefits of any advisory fees paid are to see if they can be deducted as a bona fide business expense. As while miscellaneous itemized deductions, including investment advisory fees, have been temporary repealed by the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, IRC Section 162 continues to allows businesses to deduct expenses that are ordinary and necessary… which may include fees paid to a financial advisor!

Obviously, in order to deduct any fees as a business expense, a client must have a business. But many financial advisors do work with small business owners, and in such situations, advisors should carefully review their services provided to see if they can substantiate whether at least some portion of those services and/or advice are attributable to the business. Any such services rendered to the business can then be billed to and paid by the business, making the expense a (deductible) expense of the business.

Just some of the advice services that might reasonably be attributed to a business include advice related to:

- Succession planning

- Mergers and acquisitions

- Employee benefits

- Retirement plan services

- Risk management

- Asset protection

- (Business-related) tax management strategies

In situations where advice can be reasonably attributed to both a client’s business, and the client personally, an advisor’s fee may be able to be split and reasonably apportioned, between the two. Notably, this is not all that different than a CPA apportioning the overall fee for tax preparation to a client’s own personal income tax return (also formerly deductible as a miscellaneous itemized deduction, but no longer), the Schedule C business return (still deductible), and the Schedule E return (still deductible) for supplemental income, such as rental properties.

From a practical perspective, this sort of apportionment would be easiest for those advisors billing clients by the hour, or on a project basis, as determining a reasonable value for the time spent on business-deductible planning items would be relatively simple.

Suppose, however, that a business owner has a $1 million managed joint account that is subject to a 1% AUM-based fee. Thus, the total annual fee is $10,000. Further suppose that the advisory agreement stipulates that the 1% AUM fee is for “asset management and financial planning,” or has some sort of similar language and that the actual financial planning completed includes both business-related and non-business-related items. How would you go about determining a reasonable amount that could be deducted as an IRC Section 162 business deduction?

First, you’d probably have to assign some portion of the AUM-based fee to the actual management of the joint account, which clearly would not be deductible. Let’s say 60% of the total fee is attributable to the asset management. That leaves 40% that could reasonably be attributable to planning, and if the total time spent on planning was split evenly between personal financial planning and business-related financial planning, it would be reasonable to allocate 50% of the 40% of the financial planning fee – or 20% of the overall fee – to deductible business expenses. Thus, it would be reasonable to try and claim a $2,000 business deduction in such situations.

Of course, that brings up another issue. How will that $2,000 actually be paid? If the business in question is a sole proprietorship, then it might work to simply have the AUM-based fee pulled directly from the account, as is the standard practice for many firms – and then to simply have the business owner’s accountant allocate 20% of the total cost of the fees to the owner’s Schedule C. Since with a sole proprietorship, expenses of the individual are (or at least can be) expenses of the business anyway, without being paid from a separate business account (so it’s all in the owner’s name anyway).

Note that even for this type of planning to work, though, the expenses must be paid by a taxable account, as any fees paid from any IRA should only be for the IRA (and not the account’s personal accounts, nor certainly on behalf of his/her business). In other words, while a sole proprietor can pay "business" expenses from a "personal" account, only taxable accounts are treated as "personal" accounts, as IRAs are treated entirely separate and distinct unto themselves (as discussed further below).

And what if the business is an S corporation? In such a situation, the best course of action would be to have the S corporation directly pay its portion of the advisory fee. Yet that may not be operationally efficient – or even possible – for the RIA. Alternatively, though, the S corporation could reimburse the employee/business owner for the planning expense under an accountable plan. An even better – and an easier approach to defend in the event of an IRS inquiry – might be to lower the AUM-based fee for the joint account to 0.8%, and to engage the business in a separate financial planning or consulting contract for $2,000.

Deducting IRA Fees From IRA Accounts

For registered investment advisors, the next simplest approach to helping individuals minimize the impact of the loss of the deduction for investment advisory fees is to encourage (and allow) the payment of fees from the most tax-efficient source.

In practice, AUM-based investment advisory fees (i.e., an annual fee of 1% of AUM, usually billed monthly or quarterly) are paid “on auto-pilot” by being pulled directly from the accounts to which they are attributable. For example, the fees attributable to an individual’s IRA will be pulled directly from their IRA account, and fees attributable to their taxable account will be pulled directly from their taxable account. This is indisputably allowed under Treasury Regulation 1.404(a)-3(d).

Alternatively, the IRS has consistently allowed the payment of AUM-based investment management fees (but not commissions) attributable to traditional IRAs and/or Roth IRAs to be paid with “outside” funds. Thus, for example, a client could pay a traditional IRA’s fee by simply writing a check for that amount to the RIA. Or, if the client had a taxable account with the same RIA, the RIA could “in-direct bill” the taxable account for the traditional IRA’s fees.

Notably, though, a client cannot use an IRA to pay the advisory fees for non-IRA (i.e., outside) accounts, as doing so would constitute a prohibited transaction (effectively using the pre-tax IRA to the account owner’s “personal” expenses in the form of their advisory fee for personal accounts).

Which means, in practice, financial advisors have a choice in how to bill fees (and clients have a choice in how to pay): pro-rata (where each account pays its relative share), or “all” from outside taxable accounts (leaving the IRAs intact). Each of which has its own tax consequences.

Pay Roth IRA Fees With “Outside” Taxable Funds

For years prior to 2018, even though taxpayers were generally able to take a deduction for investment management fees, fees attributable to Roth IRAs were not deductible because they were not for the production of taxable income. Just as advisory fees attributable municipal bonds were prohibited from being deducted, so too were the fees attributable to Roth IRAs, as both investments are meant to produce Federally-income-tax-free income, and not taxable income, for which the deduction is allowed.

Nevertheless, to the extent possible, it was still better to pay Roth IRA fees with outside taxable dollars. By doing so (instead of having the Roth IRA fees pulled from the Roth IRA account), taxpayers were allowing an amount equal to their fee to remain in the Roth IRA, growing tax- and penalty-free, while paying that amount with taxable funds, for which every dollar of future interest, dividends, and capital gains would have otherwise been taxable.

Since the advisory fees attributable to Roth IRAs were never deductible in the first place (because Roth IRAs produce federally-tax-free income), the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act did not change the calculus, and it is essentially business as usual. Such fees should continue to be paid with outside taxable funds, not because of the tax treatment of the fees, per se, but simply to allow the maximum amount of money inside the Roth IRA to grow tax-free.

Carefully Analyze How To Pay Traditional IRA Fees

Prior to the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, taxpayers who were eligible to take a deduction for their investment advisory fees were also generally better off paying the fees attributable to their traditional IRAs with outside, taxable funds (as opposed to having those fees “pulled” directly from the IRA). Under the old rules, both options allowed pre-tax payments (assuming the outside fee was deductible in the first place). But using outside funds offered the added benefit of leaving as much as possible inside the traditional IRA growing tax-deferred. Accordingly, it was really only advantageous to pay an IRA fee from the IRA if the fee was not otherwise going to be deductible on its own (e.g., due to the 2%-of-AGI limitation on miscellaneous itemized deductions, or due to the AMT).

Now, however, when it comes to the payment of traditional IRA fees, there’s a balance that must be weighed. Paying the traditional IRA fee with outside funds allows generally pre-tax IRA funds to continue growing tax-deferred. On the other hand, paying the traditional IRA fee from the traditional IRA essentially allows a taxpayer to receive a “pseudo-deduction” by paying an after-tax bill with pre-tax funds.

For example, suppose an individual has a $10,000 advisory fee for an IRA. That fee could be paid with “outside” funds. Doing so would allow $10,000 of pre-tax IRA money to remain in the account growing tax-deferred, but the “price” for making that choice would be paying the bill with $10,000 of after-tax dollars in a taxable account. Alternatively, the $10,000 could be “pulled” directly from the traditional IRA. This would reduce the amount of money growing inside that account on a tax-deferred basis, but would allow the $10,000 bill to be paid with entirely pre-tax funds.

So which option should clients pick?

Unfortunately, there is no always-correct answer. All else being equal, it’s always better to get pre-tax treatment for an expense – which would mean paying the fee from the IRA to the extent possible. But all else is not equal, given that choosing to pay the fee with after-tax funds allows an investor to maintain a larger pre-tax IRA that itself can get years, or even decades, of tax-deferred compounding growth. Which means eventually, the value of the tax-deferred compounding growth of the IRA can be worth more than the tax deduction of the advisory fee in the first place!

Accordingly, the longer the investor’s time horizon, the higher the return, and the less tax-efficient their portfolio (i.e., higher turnover and higher tax rates), the more advantageous it is to just pay the fee from that less-tax-efficient outside account and preserve the tax-deferred compounding IRA.

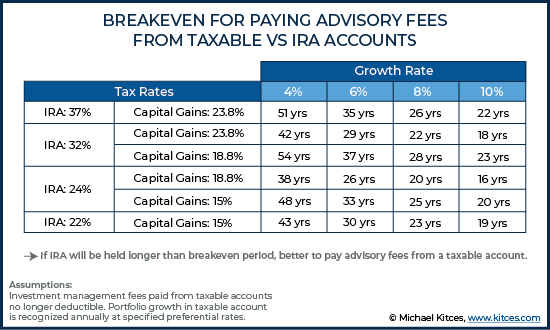

Nonetheless, the breakeven period – how long it takes tax-deferred compounding growth of an IRA to beat the tax deduction on the fee in the first place – is a rather long period of years. As shown in the chart below, even at higher rates of return, it can take nearly 20 years before the value of tax-deferred compounding growth is worth more than drawing the pre-tax fee from the IRA. At lower rates of return – in light of today’s high valuation environment – the breakeven period can extend to 30-40 years or more. And notably, these projections assume gains are turned over annually each year. If the taxable account’s turnover is more modest, the breakeven periods would be even longer!

One important caveat for advisors to consider is that only fees related to the production of income (i.e., for actually managing an investment portfolio) that fall under IRC Section 212 can be “pulled” directly from a client’s retirement account. Thus, for instance, the portion of a client’s advisory fee that is attributable to financial planning, or other services not directly associated with the production of income, was not eligible for a tax deduction under the old rules and cannot be “pulled” from an IRA. Because a financial planning fee is not an investment expense of the IRA, it’s a personal financial planning fee of the owner that would at the least be treated as a taxable distribution (if not a prohibited transaction). Notably, this attributable-to-the-production-of-income requirement is not new and was not impacted by the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. Rather, it is simply a rule that is now more relevant in a world where advisory fees are not deductible at all in outside accounts, which makes it more appealing to pay them directly from an IRA – at least, to the extent permitted.

In fact, some RIAs have tried to proactively address this issue by stipulating within their advisory agreements that their fee is expressly for asset management, and that any financial planning performed by the firm is gratis, or at least merely incidental, and solely at the discretion of the client. (Whether or not such arrangements would hold up under IRS scrutiny is not entirely clear, if the reality is that the financial planning services really are a substantive portion of the total services rendered for the fee.)

More generally, though, the challenge is simply that as investment management has become increasingly commoditized in the eyes of many consumers, many advisors have positioned “financial planning” as their primary value proposition. In such situations, the attribution of the firm’s fee entirely to investment management, coupled with “giving away” the “most valuable” stuff may send an ambiguous message to the public, while focusing the fee as being for financial planning may be good to reinforce the advisor’s value proposition… but undermine the permissibility of having the fee paid from the IRA.

Nonetheless, the bottom line is that in the current environment, when investment advisory fees are no longer deductible at all in outside taxable accounts, it’s more appealing than ever to at least bill a pro-rata portion of the advisory fee from the pre-tax IRA. At least to the extent that it can reasonably be claimed as an investment management fee of the IRA in the first place.

Selectively Locating Accounts Within Pricing Tiers – An Aggressive Strategy?

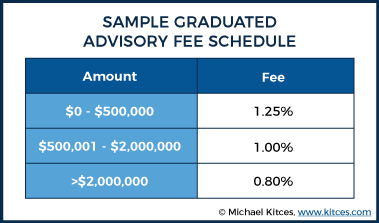

Many RIAs bill clients using a tiered approach for billing assets under management, such as the following hypothetical graduated fee schedule:

In general, the most accepted method of billing multiple accounts (and multiple types of accounts), when aggregated across a household in order to reach the specified breakpoints, is to prorate each account at each different billing tier.

Example #1: Karl has a $1 million traditional IRA, a $1 million Roth IRA and a $1 million taxable account invested with an RIA that uses the fee schedule noted above.

The standard practice in billing these accounts would be to bill each tier using a weighted average of the accounts. Here, since the accounts are all equal in value at $1MM, $166,667 from each account ($500,000 total at 1.25% tier / 3) would be billed at 1.25%, $500,000 of each account ($1.5 million total at 1% tier / 3) would be billed at 1%, and the remaining $333,333 of each account would be billed at the 0.8% tier. Which would amount to each account paying an advisory fee of $9,750 (which is equivalent to simply calculating the $29,250 fee for the entire household, and allocating it 1/3rd, 1/3rd, and 1/3rd to each of the three equally weighted accounts).

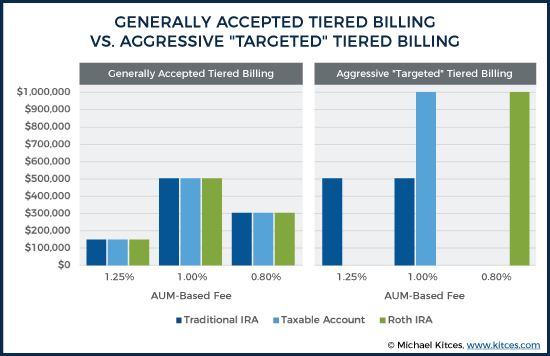

While the above-referenced method of billing multiple accounts is certainly the most defensible method in the event of IRS scrutiny, some practitioners have recently postulated that a more aggressive, but more client-friendly version, of applying their fees across the various accounts.

Specifically, some have discussed the possibility of amending an RIA’s agreement to stipulate that its billing tiers are first applied to traditional IRAs, then to taxable accounts, and then to Roth IRAs.

Example #2: Recall Karl from our previous example, who has a $1 million traditional IRA, a $1 million Roth IRA, and a $1 million taxable account invested with an RIA that uses the same fee schedule as noted above.

Using the more aggressive billing structure in which traditional IRAs are the “first” asset to be billed and Roth IRAs the “last” asset to be billed, Karl would have a 1.25% fee assessed on $500,000 of his traditional IRA, a 1% fee assessed on the remaining $500,000 of the traditional IRA, a 1% fee assessed on the full $1 million value of the taxable account, and a $0.8% fee assessed on the $1 million Roth IRA.

Thus, rather than each account paying $9,750 in fees, now the IRA pays $11,250, the taxable account pays $10,000, and the Roth IRA is billed for only $8,000… effectively shifting more of the advisory fee to the pre-tax IRA, while reducing the amount allocable to the otherwise-to-be-preserved Roth IRA. (Of course, the advisor might also simply have the client pay the Roth IRA fee from the taxable account anyway.)

Certainly, this approach is novel and has some appeal, as it increases the amount of the fees paid with pre-tax IRA dollars (from $9,750 up to $11,250, producing an indirect tax savings on the extra $1,500 of the fee now paid on a pre-tax basis).

However, this is arguably still a risky and aggressive strategy, given that there’s little authority to creatively bill advised accounts in such a sequence, and if the IRS were to view the structure as the traditional IRA paying for the fees for the taxable account (a definite “no-no”), they could consider the whole arrangement a prohibited transaction, resulting in the deemed distribution of the entire IRA. And to say the least, a “strategy” that produces only a $1,500 tax deduction but creates the potential for a liquidation of the client’s entire IRA is not a very compelling risk/return trade-off in what is at best a grey area. In other words, for what for most people is likely to be a modest benefit, arguably the risk just doesn’t seem worth it.

It is an interesting thought, though, and one that hopefully one day the IRS will bless us via some sort of guidance. But until that time comes, consider either trying to get a favorable legal opinion from a very reliable source… or potentially up your E&O coverage!?

Commission Options For Hybrid Advisors

For more than a decade, the trend within the financial “advice” industry has been to move away from commission-centric business models, and towards more fee-centric, primarily AUM-based business models. To that end, many professionals have given up their “broker” license(s) (typically the Series 6 or Series 7 license) to go RIA-only, or are planning to make that move in the near future. Many financial professionals, however, continue to work as “hybrid” advisors, maintaining affiliations with both a broker/dealer and a Registered Investment Adviser.

And ironically, while both the business and regulatory trend has been to move away from commissions and towards fees, for taxable accounts, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act distinctly favors commissions with respect to tax efficiency of how the client compensates their advisor.

This tax efficiency can manifest itself in several ways. Consider the following example:

Example #3: Sarah is a hybrid advisor who is starting a relationship with a new client, Sam. Sam has $1 million in a taxable account and is agnostic as to how he pays for “advice” as long as it’s tax efficient.

After careful analysis of Sam’s situation, Sarah is planning to invest Sam’s money in an individual stock portfolio, consisting of 20 positions, and for which she expects there to be 50% turnover during the year.

To clearly illustrate the tax efficiency of commissions over advisory fees under the new tax regime, let’s suppose that on January 1st, Sarah engages with Sam and invests his portfolio into her model. During the year, the account’s positions increase in value by 10%. However, on December 31st of the same year, concerned about a recession, Sarah liquidates the portfolio and moves Sam to cash.

With that in mind, let’s analyze the tax impact of two equal-revenue-generating scenarios for Sarah:

- Advisory Agreement: Suppose that Sarah bills her 1%-of-AUM fee quarterly, but based on the January 1st value of the account. As a result, Sam would owe a $10,000 investment advisory fee for the year in question. This advisory fee is not deductible, and does not have any impact on Sam’s basis in the securities within his account.

Under Sarah’s management, Sam’s account grew in value by 10%. Thus, Sam will owe income tax on $100,000 (10% times $1 million) of capital gains.

Thus, Sam’s total cost for the year related to his portfolio are $10,000 of advisory fees, plus tax on $100,000 of income.

- Brokerage Account with Commissions: Now, let’s suppose that, instead of being compensated by a 1% advisory fee, Sarah establishes a brokerage account for Sam. Furthermore, Sam and Sarah agree that Sam will pay a $500 commission on each transaction that Sarah makes during the year, up to a maximum of $10,000, and that after reaching the $10,000 mark, Sarah will continue to trade the account commission-free for the remainder of the year. As a result, Sam’s total cost for “advice” would be the same $10,000 in our previous scenario.

However, any commissions paid by Sam on a purchase will add to the cost basis of his investment. Similarly, any commissions paid by Sam on a sale will reduce the proceeds of that sale. As a result of the combination of basis increase and/or proceeds decrease afforded by the commissions paid by Sam, he will owe tax on “only” $90,000 of capital gains. Note that this is in direct contrast to advisory fees, which have no similar impact on basis.

Thus Sam’s total cost for the year related to his portfolio are $10,000 of commissions, plus tax on $90,000 of income. By virtue of the pseudo-deduction afforded by this engagement’s commissions which add to cost basis (vs. the advisory agreement’s fees which do not), Sam has saved an amount equal to his income tax on $10,000 of capital gains!

For advisors primarily using mutual funds within their models, the transition to a commission-centric, pseudo-deductible model might be even easier. That’s because many mutual funds have different share classes and, all things being equal, a client with a taxable account is better off (from a tax perspective) having their financial professional’s compensation arising from (much maligned) taxable-income-reducing 12b-1 fees, rather than via advisory fees.

Put differently, individuals are actually better off (from a tax perspective) having C shares with a 1.5% expense ratio (including a 1% 12b-1 trail) in a brokerage account than having an advisory account for which they are billed a 1% AUM fee and hold institutional versions of the same funds with average expense ratios of 0.5% (removing the 1% in 12b-1 fees). The total fee paid by the account owner, in either case, is the same, but the tax treatment is not!

Example #4: Eric is a hybrid advisor who is starting a relationship with a new client, Agnes. Agnes has $1 million in a taxable account and is agnostic as to how she pays for “advice” as long as it’s tax efficient.

After careful analysis of Agnes’s situation, Eric is planning to invest Agnes’s money in portfolio consisting of 10 mutual funds.

To illustrate the tax efficiency of the C-share model over the advisory model under the new tax regime, let’s suppose that on January 1st, Eric engages with Agnes and invests her portfolio into his model. Further, let’s suppose that during the year, the mutual funds Eric selects produce income and dividends equal to 3.5% of the invested funds.

With that in mind, let’s analyze the tax impact of two equal-revenue-generating scenarios for Eric:

- C-Share Arrangement: If Eric chooses to utilize C shares for Agnes, the 1.5% expense ratio of the mutual funds will be subtracted from the 3.5% of interest and dividends generated by the mutual funds, resulting in “only” 2% of taxable distributions from the fund at the end of the year. Therefore, Agnes’s total cost for investment “advice” will equal $15,000 ($1MM × 1.5%), but she will owe income tax on only $20,000 ((3.5% -1.5%) x $1MM) of the income generated from the funds. The commissions are effectively pre-tax because they are paid from (and subtracted directly from) the income of the mutual fund before it becomes taxable to the end investor.

- Advisory Agreement with Institutional Shares: Suppose, however that Eric opted for the generally-more-accepted route of using institutional share class versions of the same funds, but in a managed account with a 1% AUM fee. Here, assuming the institutional shares have an average expense ratio of 0.5%, Agnes will have the same total fee for investment “advice” of $15,000. However, since the expense ratio of the funds is now “only” 0.5%, Agnes will owe income tax on $30,000 ((3.5% - 0.5%) x $1MM).

In this situation, Agnes is clearly better off, from a tax perspective by utilizing the C share mutual funds in her planning. Her tax savings, going that route, is equal to her tax rate multiplied by the $10,000 less of income on which she must pay tax.

Notably, though, there are growing regulatory concerns with holding substantial amounts of C shares for long periods of time, and in recent years a number of asset managers have begun to automatically convert long-standing C shares into A shares (reducing the cost of the fund, but also the trails revenue to the advisor), under the auspices that a levelized commission for an upfront sale (which is functionally what a C-share mutual fund is) shouldn’t continue indefinitely after the one-time sale. As such, advisors considering this option should be sure to check with their compliance department to understand their protocols and guidelines regarding the use of C shares. Furthermore, even if such shares are allowed to be used for prolonged periods of time, advisors should carefully – make that very carefully – document the reason for their use over other potential investments.

Transition Your Firm’s Models To Mutual Funds/ETFs

Hybrid advisors and brokers aren’t the only financial professionals whose clients may be able to benefit from the use of mutual funds, however. For instance, another way that RIAs can help their clients offset the loss of the deductibility of investment advisory fees is to transition their own use of internal model portfolios, or separately managed account (SMA) models, to being restructured as mutual funds or ETFs.

In other words, rather than XYZ advisory firm having a series of “conservative,” “moderate,” and “aggressive” portfolios, which the advisory firm manages, and from which (non-deductible) advisory fees are paid… the advisory firm could instead establish its own mutual fund or ETF (or series of them), and then give clients the option to invest into XYZ Conservative ETF, XYZ Moderate Growth ETF, or XYZ Aggressive Growth ETF.

The primary benefit of this approach is to allow for the same pre-tax payment of fees as brokers using the commission model. However, the primary difference is that in order to avoid the necessity of a broker/dealer relationship, the RIA would not “sell” the mutual funds (or other investments) and collect 12b-1 fees or other commissions. Rather, the RIA would create and register a mutual fund or ETF, become the sub-advisor to the mutual fund/EFT, bill the mutual fund/ETF directly for advisory services rendered pursuant to an investment management fee with the fund, and the mutual fund/ETF would pay those advisory fees via the expense ratio(s) from its fund(s) – which, as noted earlier, are implicitly pre-tax since those expense ratio fees are subtracted from the income of the fund before any taxable income is distributed to fund shareholders in the first place!

Of course, this strategy only has the potential to work if the RIA is model-based, or at least is willing to become model-based. Though for a variety of reasons, not the least of which is the ability to scale, a growing number of advisors already run their businesses by placing clients into one or more standardized models.

However, while from a client’s point of view, the repackaging of a separately managed account or other model-based investment strategy into a mutual fund or ETF may offer a “simple” way to pay investment management fees on a tax-efficient basis, there is are several significant challenges on the advisor side of the equation.

Creating And Maintaining Funds Can Be An Expensive Proposition

For most advisory firms, the biggest blocking point to restructuring the firm’s investment offer as a series of mutual funds or ETFs may simply be the cost; initial registration costs often run upwards of $100,000, and ongoing costs related to accounting, administration, audits, compliance, legal, custody, and other elements of the business are likely to exceed six-figures annually as well. And remember, those fees are separate from the actual advisory fees that the RIA would want to bill the mutual fund or ETF to generate its revenue!

To make matters worse, many RIAs would have to establish and maintain more than one mutual fund or ETF to continue their current investment management strategies uninterrupted, given that most firms have a range of models for clients, not just one solution. For instance, suppose an RIA typically places its clients and one of five models ranging from conservative to aggressive. In such a case, in order to maintain the same investment philosophy, instead of simply creating and maintaining one mutual fund/ETF, the RIA might have to create a series of five separate funds; a conservative fund, a moderate conservative fund, a moderate fund, etc. For which there are some cost efficiencies – as creating a series of five funds in a single offering is less expensive than just making 5 standalone funds – but would still increase the total cost significantly for the typical advisory firm.

Alternatively, an RIA could, perhaps, create one equity mutual funds/ETF, and one fixed income mutual fund/ETF, and blend them together to varying degrees to achieve a desired overall client portfolio (effectively reducing from five potential funds and ETFs into “just” two). This may, however, require the RIA to change its investment philosophy somewhat, as many advisors not only reduce the amount of equities they own for a client as the client becomes more conservative, but they change the makeup of those equities as well.

For instance, in an aggressive portfolio in which a client is invested 90% in stocks, and advisor might allocate 50% of the total stock owned (in other words, 50% of the 90%) to small-cap and mid-cap companies, which are typically considered to be riskier than the stock of larger companies. But if the same advisor allocates only 20% of a conservative portfolio to stock, and of that 20%, allocates only 30% of the total stock owned to small-cap and mid-cap companies, then merely shifting the allocation between the firm’s stock-fund and bond-fund would not properly reflect this kind of dynamic shift.

To combat this issue, an RIA could choose to further segment their positions into additional mutual funds/ETFs, such as creating the firm’s large-cap fund, mid-cap fund, small-cap fund, etc. By opting for this approach though, RIAs would, once again, increase their initial and ongoing costs due to the number of funds that would be required.

Which means, either way, advisory firms that consider the route of converting from a series of model portfolios into a series of mutual funds or ETFs will need to be prepared to create multiple funds to fulfill a typical range of models and client allocations… with an even higher cost than “just” the cost to create a single fund alone.

Clients May Not “Feel” Diversified Holding One Or A Small Number Of Funds

In addition to the operational problems and potentially cost-prohibitive expenses associated with the mutual fund/ETF “solution,” there are also other potential issues turning a firm’s model into a mutual fund.

Suppose, for instance, that ABC Advisors takes its moderate growth model – which currently owns 40 positions and is implemented as a separately managed account (SMA) solution for its clients – and turns it into the ABC Moderate Growth Mutual Fund.

In the month before the transition, ABC Advisors’ clients would open their custodial statements and see 40 different positions. In the month after the transition, however, the same client would open up your statement and see one position… the ABC Moderate Growth Fund. That ABC Moderate Growth Fund could own exactly the same positions in exactly the same percentages as the client had owned previously via their SMA, in which case the client would technically be no more or less diversified as a result of the change in implementation. However, chances are that when the client opens their statement and sees the one mutual fund, they won’t feel as diversified as they were when they owned the same 40 positions, but individually.

Simply put, client psychology matters… a lot. And although it’s not a reflection of the reality of diversification, consolidating into a mutual fund or ETF structure may feel less diversified to the typical client. A challenge that should not be underestimated.

The Tax Challenges Of Converting Existing Portfolios To A New Approach

And ironically, while the whole point of this endeavor would be to help the client keep more of their money by minimizing the bite of taxes, transitioning from an existing model portfolio to a mutual fund/ETF model might actually hurt clients from a tax perspective if their investment is made with taxable money. For instance, how would the RIA transition clients from their current model account holdings into a mutual fund? Will they simply liquidate the account and purchase their newly established mutual fund?

Operationally, that’s probably the most efficient way of making the transition, but after a decade-plus long bull market run, chances are that many clients would have highly appreciated individual positions within their accounts. Thus, selling those positions to reinvest the funds into a mutual fund model of the same positions could trigger substantial taxable income in the form of capital gains. And while an advisor could choose not to sell certain individual positions in the account, the uniformity and non-customizable-ness of a mutual fund means that any position held for tax purposes might be overweight from an asset allocation standpoint when it is purchased again indirectly via the mutual fund.

This is not the only potentially harmful negative tax impact though. Even in situations where new investments are made with cash, the mutual fund/ETF model might ultimately prove to be tax-inefficient! And it’s not hard to see why…

Simply ask yourself, “Why do many high-net-worth, high-income taxpayers prefer separately managed accounts as opposed to mutual funds when it comes to their taxable dollars?” The answer, of course, is tax efficiency! The ability to separately identify, buy and/or sell positions – whether to more granularly harvest capital losses or capital gains – is a major benefit of a separately managed account as compared to a mutual fund or ETF.

Example #5: 123 Mutual Fund purchased shares of Blue Company on January 1, 2018. During 2018, Blue Company increase substantially in value, by some 20%.

On January 1, 2019, Marjorie purchased shares of 123 Mutual Fund. Unfortunately, 2019 is a tough year, and by the end of the year, Marjorie’s investment in the fund has decreased by 5%. Furthermore, during the same period of time, the shares of Blue Company owned by 123 Mutual Fund, decreased by 10%. Thus, 123 Mutual Fund has a net gain of 8% on its Blue Company shares from purchase in early 2018 through to the end of 2019.

Now, suppose that 123 Mutual Fund's manager sells all the shares of Blue Company on December 31, 2019. Although both the shares of Blue Company stock owned by 123 Mutual Fund, as well as the fund itself, have decreased in value since Marjorie’s purchase, Marjorie will be passed through her share of the 123 Mutual Fund’s gain on the shares (since their original 2018 purchase). Thus, despite losing money, Marjorie will have taxable income (which could be reduced if she sold her 123 Mutual Fund at a loss in 2018 – but while doing so might provide a tax loss harvesting benefit, it would in turn require Marjorie to wait more than 30 days to repurchase the 123 Mutual Fund to avoid the wash sale rule. That might not be good for Marjorie – if the fund increases substantially during that time – and it’s certainly not good for 123 Mutual Fund’s business).

In contrast, if 123 Mutual Funds was running the same strategy as a separately managed account, the result would’ve been much different. Not only would Marjorie have avoided a capital gain, but she would have had a capital loss (to either offset other capital gains, or to offset up to $3,000 ordinary income), because her specific shares of Blue Company would have been lower by 10% since their purchase within her account.

The tax benefits to “selectively select” discrete positions to buy and sell within a taxable account cannot be overlooked. The ability to efficiently harvest losses, and to manage gains, is a significant benefit for many taxpayers. And in many cases, the loss of this ability could more than offset any benefits associated with the tax efficiency of fees in the mutual fund/ETF model.

Utilize Limited Partnerships To Make Advisory Fees Deductible Again?

Yet another way that financial professionals can try to relieve the burden of the loss of the miscellaneous itemized deduction for their clients’ advisory fees is to restructure their investment offering as limited partnerships.

The basic purpose of the structure would be, similar to converting to a mutual fund or ETF, the opportunity to turn a non-deductible advisory fee to the client into a “management fee” of the investment partnership as an entity, converting a non-deductible fee into a deductible one. And hopefully, at a lower upfront and ongoing cost than the relatively prohibited expense of creating a mutual fund or ETF (or a series thereof) in the first place.

However, the limited partnership approach is not without its own challenges. From a regulatory perspective, such investments would almost certainly not be registered securities, which means the partnerships would be treated as private securities, and thus, generally available only to high-net-worth and other accredited investors. More substantively, though, is simply the challenge of legitimately being able to claim management fees of the partnership as an expense beyond just an already-non-deductible advisory fee.

Claiming The Limited Partnership Is A Business… A Tough Row To Hoe

One way that advisors can try and utilize limited partnerships for better fee deductibility is to try and “prove” to the IRS that the partnership, itself, is engaged in a trade or business, and is not “merely” an investment.

If the limited partnership is deemed to be “just” an investment, then the expenses associated with the partnership will be deemed investment fees, passed through to the individual partners (as a pass-through entity), and end out not being deductible on the partners’ individual tax returns. Alternatively, if the limited partnership is deemed a standalone business of its own, then the ordinary and necessary expenses associated with that business would be deductible as business expenses.

This may sound simple, but historically, getting the IRS to accept the partnership’s “business” status has been… murky at best, and difficult at the least.

Nonetheless, in December of 2017, the Tax Court issued its decision in Lender Management, LLC, et al. v. Commissioner. The case involved an LLC taxed as a partnership (Lender LLC) that was serving as a family office of sorts for three separate investment entities owned by various members of the Lender family. Lender LLC was largely responsible for the investment decisions on behalf of the various family-owned entities which it serves, and it claimed a host of “business” expenses related to its management, research, operations, etc.

The IRS challenged those expenses, claiming that they were investment expenses and not business expenses, and thus, not deductible by Lender, LLC. The Tax Court, however, held that based on the evidence presented at trial, Lender, LLC was, in fact, engaged in a trade or business, and thus, was able to deduct such investment management fees as expenses at the entity level.

Thus, some firms may wish to try and emulate the Lender, LLC setup. However, given the relatively grey area determining whether expenses are investment expenses or business expenses of the partnership, advisors may wish to look to a more definitive way to use limited partnerships to help mitigate the impact of clients’ loss of itemized deductions.

Carry On With Carried Interest

The term “carried interest” refers to a general partner’s allocation of the profits of a partnership, in accordance with the partnerships operating agreement. Historically, this is how private equity or hedge funds have collected their performance-based fees. In essence, the way a “carry” works is that, instead of actually paying the general partner for their management (or performance) fee via cash (taxable as ordinary income), they are actually given a piece of the partnership and its upside (potentially taxable at capital gains rates upon sale). That allocation is their “carried interest,” or simply their “carry.”

There is nothing, however, stopping an RIA or other investment manager from establishing a limited partnership and similar compensating themselves in such a manner. And while the term “carried interest” is usually referenced as a “loophole” for large private equity firms or hedge fund managers (who may earn most, if not all, of their compensation via the “carry” at long-term capital gains rates), from the investor’s perspective, the manner in which the allocation of a carry impacts limited partners’ taxable income can be more beneficial than a traditional (no-longer-deductible) AUM fee!

The reason the carried interest payment has the potential to benefit limited partners from a tax perspective is because the carry is allocated to the general partner at the partnership level, and therefore reduces the amount of taxable gains that are attributable (and taxable) to the limited partners. Effectively, it functions much like a mutual fund expense ratio, “coming off the top” and reducing the income of the partnership before it even generates its pass-through income to investors.

It's important to remember, though, that the “carry” only relates to the general partner’s allocation of partnership profits… which necessarily makes it a performance-based fee! Since AUM-based “management” fees are generally calculated without regard to performance, they cannot be converted to a carried interest.

However, while the compensated-by-carried-interest structure may have appeal to some investment managers, it could present substantial problems for most investment advisors. For starters, as a non-registered, private security, the partnership would, once again, be available primarily to accredited investors. Thus, the clients of many advisors could not be served by such a structure.

Such a structure could also introduce substantial business risk for the advisor. Recall that the carry is a portion of the partnership’s profits that are allocated to the general partner. But what if we head into a bear market and there are no profits for the next few years?! Most advisors wouldn’t be able to wait three years for their next paycheck!

And finally, such structures could also have a negative influence on the advisor’s overall investment philosophy. The more the advisor is compensated by (out)performance, the more the advisor has a reason to take extra, potentially unnecessary or imprudent risk to achieve a higher return. In fact, the undue incentives of risk-taking by investment managers on behalf of their investors with a performance-based fee structure are precisely why performance-based fees are generally limited to accredited investors in the first place and are not commonly allowed in most traditional RIAs.

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act dramatically changed the tax landscape to a depth not seen by most advisors during their years in practice. Not surprisingly, most financial professionals are still dealing with the fallout of the law, and are trying to figure out how to best position their clients and the business models to take advantage of new benefits while minimizing the loss of others.

The elimination of itemized deductions and specifically the IRC Section 212 deduction for expenses associated with the production of income is particularly important to advisors, as investment management fees are no longer deductible on the personal income tax return. Nevertheless, there are a host of steps that advisors can take to minimize the loss of this deduction, ranging from simple let’s-figure-out-how-to-efficiently-pay-your-fees strategies, to the ultra-complex repackaging of model portfolios into mutual funds and ETFs (or limited partnerships).

At the end of the day, though, the bottom line is that many investors are appropriately disappointed that they’ve lost the ability to deduct investment advisory fees. Yet while advisors don’t have the ability to reverse the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act’s changes, depending upon a client’s circumstances and an advisor’s business model, there may be a number of ways to potentially mitigate the loss of the advisory fee deduction and preserve at least some of its pre-tax treatment.

Great in depth article. It looks like until there is some serious lobbying that is going to need to be done, in the meantime it looks like AUM fees are going to be at a tax disadvantage.

Please visit: investment synonym

@jefflevinecpacfp:disqus – any thoughts on an investment IRA paying the freight of an annuity-based IRA with living benefits? I know the fee for the annuity-based IRA could be paid from non-retirement accounts. I also know that the IRS treats all IRAs for an individual to be one “account” when calculating RMDs. Would they look at the investment IRA paying the cost of the annuity-based IRA in a similar manner? I haven’t seen anyone comment on this potential issue. Thanks!