Executive Summary

The traditional approach to evaluating risk tolerance - which has been enshrined into our standard regulatory process for determining the "suitability" of a recommendation - involves gauging a client's attitudes about risk, their financial capabilities to take risk (e.g., time horizon, need for income, and availability of other assets), and mixing them together into a composite score that can be assigned to a portfolio. A strong attitude and financial ability to take risk gets a high score and an aggressive portfolio, a poor attitude for risk and significant portfolio needs result in a conservative portfolio, and a mixture of the result leads to a moderate growth portfolio in the middle.

Yet the fundamental problem with this traditional approach is that it confuses someone's capacity to take risk with their actual need or desire to do so. The end result is that wealthy clients who don't want or need risk end out being given moderate growth portfolios anyway, young clients who have a long time horizon but no desire for risk end out with equity-centric portfolios that may scar them for life, and clients who have unrealistic spending goals end out with impossibly conservative portfolios doomed to fail.

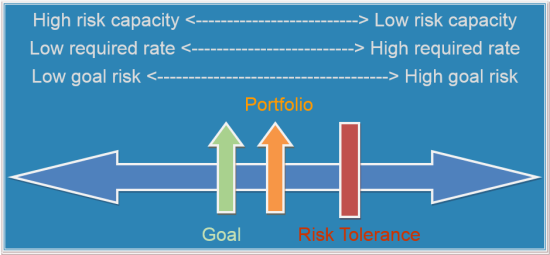

The solution to this challenge is a fundamental change to how we view risk tolerance and financial risk capacity in the first place. The optimal portfolio solution is not a combination of risk tolerance and risk capacity; it's the portfolio that can best achieve the client's goals, constrained by risk tolerance to ensure that neither the portfolio, nor the goal, exceeds the client's tolerance in the first place. In other words, it's absolutely crucial to separate out our evaluation of whether someone needs risk, whether they can afford risk, and whether they want to take risk, so that the ultimate portfolio recommendation can properly align all three.

Defining Risk Tolerance And Risk Capacity

In the standard process of evaluating "risk tolerance" there are usually a wide range of questions regarding both someone's financial and their mental ability to manage risk and withstand risky events.

The financial questions - which might related to their need to tap the assets for income/withdrawals, the time horizon of the goal, and the availability of other assets - speak to the person's risk capacity. In other words, to what extent could a "risky event" happen (e.g., a market crash) without damaging the underlying financial goals. If you don't need money for decades (i.e., long time horizon) a near-term disaster won't impact goals. If you aren't withdrawing anything from the portfolio and it's just a small slice of overall net worth, again a near-term disaster won't impact goal. These would be clients who have a high capacity for risk. By contrast, if the goal is to take significant ongoing withdrawals, starting immediately, there is a far lower capacity for risk; if "something bad" happened, the goals would be in serious danger.

Once separating out the purely financial matters, true risk tolerance becomes purely focused on a client's actual attitudes about risk. In other words, does the client actually have the mental inclination and desire to pursue a more favorable outcome at the risk of a less favorable result. Notably, these mental attitudes about risk have nothing to do with the ability to afford the risk - it's simply about the desire to pursue actions or goals that entail risky trade-offs (or not).

From this perspective, risk capacity actually becomes a measure of how risky the client's goals actually are; i.e., do the goals require a high rate of return just to have a chance of success, or is the goal so low risk that even a bad market outcome can't derail it. Risk tolerance measures how much of a risky trade-off the client is willing to pursue, whether that be expressed in the portfolio the client invests in, or the goals that the client aims to achieve in the first place. The simple key: it's crucial to be certain that neither the portfolio, nor the goal, is riskier than what the client can actually tolerate.

As the illustration shows, the client has a relatively conservative goal on the spectrum, a portfolio that should be able to achieve a return slightly in excess of that necessary to achieve the goal, and both the portfolio and the goal are more conservative than (i.e., to the left of) the client's maximum level of risk as indicated by their risk tolerance.

Why Separating Risk Tolerance And Risk Capacity Matters

To understand why this distinction between risk tolerance and risk capacity is so important, imagine two hypothetical clients: John Smith, and Betty Burton. Both clients are highly adverse to risk; if you gave them a questionnaire that just asking about their attitudes and willingness to take risk, both would earn the lowest possible scores. If you asked them "In a bear market, would you: A) Buy more; B) Just hold tight and stay invested; or C) Sell some of your portfolio" they'd answer "D) SELL EVERYTHING IMMEDIATELY!"

From the goal perspective, John's plan is to retire in about 15 years. His income goal is about $15,000/year, from a portfolio projected to be at $1,500,000 by then. Accordingly, John has what we'd call a "high capacity for risk"; if someone horrible happens in the market, his future withdrawal rate will go from 1% to 2%, which is still extremely conservative and safe. In other words, even if something bad happens to John's portfolio, his goals will be fine, and he has a high capacity for risk.

Betty's plan, on the other hand, is to start tapping her portfolio immediately, and she needs about $65,000/year (inflation-adjusted) from her $1,000,000 portfolio to achieve her goals. As a result, Betty actually has a rather low capacity for risk; if something bad happens to her portfolio, her goals are in serious jeopardy, as a 6.5% withdrawal rate is a dangerous proposition. Or viewed another way, Betty's goals themselves are very risky to pursue.

Using a "traditional" risk tolerance questionnaire approach, John would answer a long series of questions about both his financial capacity for and mental views about risk. His long time horizon and low need for income would give "high" scores, while his poor attitude about portfolio risk ("SELL EVERYTHING IMMEDIATELY!" in a bear market!) would get a low score. The likely end result: John would get a score around the middle on the overall questionnaire, and end out with a moderate growth portfolio.

Using a similar traditional risk tolerance questionnaire approach with Betty, the responses regarding financial capacity would indicate a limited time horizon and a high need for income, while Betty too would show a low tolerance for actual portfolio risk. The end result is that Betty would likely get one of the lowest scores possible on the risk tolerance questionnaire, and accordingly would receive an ultra-conservative bond portfolio.

It's crucial to note the outcomes achieved with the traditional approach. John has received a portfolio that virtually ensures he will someday have a personal financial crisis, because we've given a client with no actual tolerance for market declines a moderate growth portfolio! And the problem is not unique to John; in fact, we've also given Betty a portfolio that virtually ensures she will also someday have a personal financial crisis, because we've given an all-bonds-and-cash portfolio to a client who's targeting a 6.5% withdrawal rate!

The end result of the traditional approach: two clients on the road to personal crisis and potential disaster! For John, it's because he received a portfolio that will give him far more risk than he can tolerate - just because he can afford it doesn't mean he should, nor did he even need that risk in the first place (remember, he just wants to spend 1%/year starting in 15 years!). With Betty, the problem is that she has a set of goals that are inconsistent with her risk tolerance, for which there is no portfolio solution; the real conversation with Betty should not be about whether to have an aggressive portfolio or a conservative portfolio to achieve her goals, but that she needs to adopt some more realistic goals that better align with her risk tolerance in the first place!

Practical Implications Of Separating Risk Tolerance And Risk Capacity

The sad reality is that the combination of risk tolerance and risk capacity into a single measure has been so enshrined into today's regulatory environment, that the aforementioned disasters for John and Betty would probably be entirely defensible to most regulators, as those portfolios were the ones indicated by the traditional (albeit very flawed) approach to risk tolerance.

Nonetheless, in doing financial planning for the best interest of the client, it seems clear that it's time to separate out risk tolerance from risk capacity. Just because clients can afford to lose money doesn't mean they should be invested to do so, whether it's a retiree with conservative spending goals (like John in the example above), or a 25-year-old young investor with a long multi-decade time horizon. This has ramifications for both the traditional advice we give young people ("you should have a mostly stock portfolio because you have a long time horizon and can afford to take the volatility" - ignoring whether they have the tolerance for it in the first place!?), and the process used with retirees (measure risk tolerance on a standalone basis, and only then compare it to their needs, goals, and time horizon). Otherwise, we risk "over-risking" young clients and giving them an early bad market experience that scars them so much they walk away from being equity investors for good, and for wealthier clients we may unwittingly put at risk capital they never wanted, needed, or intended to risk in the first place!

Of course, this doesn't excuse the importance of the other key aspect of managing risk for clients - providing the ongoing education and expectations management that's necessary to keep their perceptions of risk in line with what's actually happening in their portfolio. And it's important to recognize that there are still better and worse ways to measure risk tolerance in the first place; while many seem to prefer a "conversational" approach, advisors may unwittingly bias client responses in the manner that they ask the questions, and research has shown that even just the gender of the voice asking the question can influence the client response! Consequently, best practices should probably include some form of (psychometrically designed) risk tolerance questionnaire (that really just measures risk tolerance, not mixed with the other factors!) which can then be explored and validated with a follow-up conversation to clients.

In the end, the point of this discussion is not to say that risk tolerance questionnaires themselves are "broken" and unusable, but simply that our industry-standard process of mixing together risk tolerance and risk capacity questions on a questionnaire together is what's broken. As long as we mix together questions about whether someone can afford risk with whether they wish to take the risk, we will have outcomes where clients end out with portfolios that give them risk they cannot tolerate just because they can afford it. Once pure risk tolerance is viewed for what it should be - a constraint on portfolio (and goal) risk, regardless of time horizon and financial capacity - it becomes far easier to align tolerance, portfolios, and goals.

Great article, difficult however to explain to clients. Perhaps better for the planner to digest all the factors and make a recommendation to client based on best assessment.

In a perfect world, yes. But somewhere between the HRC and the RLC is the CYA.

Michael,

I actually completely split out risk utility from risk capacity and have observed that one can have a low capacity (say, a new retiree who is vulnerable to sequence risk) but a high risk utility. This is a substantive conflict in an of itself, regardless of risk tolerance. Thus, my investor profiles have 4 distinct factors, time horizon, risk capacity, risk tolerance and risk utility – and there can be numerous possible conflicts amongst them. Each profile is goal specific (e.g. college, retirement, home purchase, etc.) such that a client might have more than one investor profile.

I’m glad you’re (still) talking about risk capacity…you never read about it in the main stream media and to a large degree my clients don’t know what it is when they first come through my door. They typically believe that risk tolerance is all that matters – and that the risk tolerance of the person who oversees the financial matters is all that matters!!

Kay

Kay,

I’m not familiar with the term “risk utility”. Could you please explain the meaning you are giving it.

Geoff

How much risk does the client need to take in order to obtain the required returns – risk utility boils down to required return.

Thanks Kay. It sounds similar to what we would call risk required, namely, the risk associated with the return required to achieve goals from available resources.

Geoff

just a thought, but isn’t it interesting that in an example regarding risk with the four choices: A) Buy More B) Hold Tight C) Sell Some D) Sell Everything, D) is looked at as the risk averse response when it is actually a market timing action which could be looked at as one of the more risky maneuvers an investor can make.

Thank you Michael for raising a very interesting question. I would add, though, that not only do we need to separate risk capacity from risk tolerance, but we need to reconsider how we define risk. Since Markowitz, we have defined risk in terms of volatility, and while that has provided some interesting insights, is it really the proper metric for either risk tolerance or risk capacity?

In terms of risk capacity, volatility would seem to be only relevant as a function of time, since volatility decreases and eventually disappears as the time frame lengthens. In terms of risk tolerance, of course, volatility does matter since risk tolerance is entirely psychological. Yet in my experience, it is not nearly as ascertainable as implied by our use of risk tolerance questionnaires.

More than anything else it seems to me that clients’ risk tolerance varies depending on recent market experience. Back in the “good ole days” of the 1990s clients loved risk since (no matter what I said to the contrary) they thought that “risk” meant that you make more money. Then came the downturn and everyone hated risk since risk now meant that you lost money and who wanted to do that? But what had really changed? Had they undergone a true psychological shift, or were they just responding to recent experience? In either case, how useful is our risk tolerance assessment?

Perhaps of greater importance, though, is the fact that psychological risk tolerance does readily lend itself to education. Clients can learn to accept volatility for what it is; important in the short term but meaningless in the long term. What clients really fear, is not volatility at all, but the risk of permanent loss which is “a whole different kettle of fish” from volatility, and not measured at all by risk tolerance questionnaires or resolved by the “risk free” portfolios which don’t do away with risk at all, but simply exchange one kind of risk for another.

David, you have it the nail on the head with the question being how do you define risk. In our industry we equate risk with volatility. But this is only one kind of risk. Others should be inflation risk, political/economic risk (maybe this is black swan risk), risk that goals cannot be met. investment risk (for those supposedly guaranteed investments). We should be factoring in all these risks with our recommendations.

Also, diversification almost always lowers risk. Not just volatility, but other risks as well. So the idea of a non-equity portfolio being lower risk than a balanced portfolio when include other risks such as inflation risk is just wrong. And life insurance is the riskiest portfolio when the risk you are talking about is inflation risk. Wide diversification of asset types is very important to lower overall risk.

David,

Thanks for the comments.

Many of the issues you’re raising here about the “stability” of risk tolerance are actually more a function of risk PERCEPTION than actual risk tolerance. Risk perception can vary significantly with market volatility, with education, and a wide range of behavioral biases; but that doesn’t necessarily mean a person’s TOLERANCE is changing, just their perception.

For a simple example – if you REALLY TRULY believed that “tech stocks” would provide a guaranteed 20%/year return in 1999, and therefore bought a ton of them, the real issue was not “you became more tolerant of risk and bought tech stocks” but simply “you grossly misperceived how risky tech stocks are and overinvested beyond your risk tolerance”. And conversely, if you REALLY TRULY believed that stocks were going to crash to zero, it doesn’t matter how tolerant of risk you are, you sell them all before they go to zero; again, that’s not changing risk tolerance, but just misjudging how risky the stocks really are. See http://www.kitces.com/blog/does-risk-tolerance-really-change-with-market-volatility/ for some further thoughts on this.

I don’t disagree AT ALL with the great importance of client education and helping them to manage expectations. The point is simply that doing so is more about managing their unstable risk PERCEPTION, not necessarily their varying risk TOLERANCE.

– Michael

Michael,

Thanks for the, as always, thoughtful comments. That is an interesting and an important distinction that is too infrequently raised. Indeed, while familiar with FinaMetrica, I have not delved as deeply into it as, perhaps, I should have. I am certainly willing to accept that THEY may have “built a better mousetrap” and are, indeed, capable of more accurately gauging true risk tolerance. Still, I think you will agree that the typical Risk Tolerance Questionnaire utterly fails to make the distinction between Risk Tolerance and Risk Perception that you raise. The results from those questionnaires may protect US from “unsuitability claims” but say little of importance about our clients and what matters to them.

As you point out, that also leaves wide open the question of whether our clients concept of risk is really centered so much on volatility as it is on the prospect of permanent loss. If we can address the latter, would they really care so much about the former? Of course, in the final analysis there is nothing that can protect us from permanent loss (US Treasuries could default and cash is inevitably eroded by inflation), but isn’t the point then, to speak with them in terms of managing the risks that they actually face rather than focus so much on reducing mere portfolio volatility?

Good article Michael. I’ve been using Geoff’s software, Finametrica for about 4 years now and the first thing they tell you when you sign up is that the risk tolerance score is just the start of the process. I have come across too many advisors who use a score at the end and put clients into inappropriate portfolios.

If someone is a high risk taker but has more than enough money to do everything they want in life, why the need to take risk? Beating inflation should be the goal. Then like in your example with Betty, it has to be explained that she cannot reach her goals within her risk comfort zone, so she should either accept more risk, lower her expectations or save more.

Great article Michael. This is a conversation we’ve been having at my firm for quite some time. Often, we try to educate clients who have goals that oppose their capacity or tolerance. We are finding that many clients who are about to retire have capacity to take some risk if they plan appropriately, but they have little tolerance to do so.

I like what you have put here – I have often thought of risk in two ways. First is the concept of the ‘delta’ between Risk Appetite and Risk Tolerance which covers the mental side that you discuss. My wife has an appetite for jalapenos, but her stomach can’t tolerate them. Market Risk is often similar. I have also come up with this 2×2 matrix that I think would be a great potential visual for your risk tolerance v. risk capacity discussion. It’s with my own concept from a few months ago, but quite similar. http://www.myfinancialstrategies.blogspot.com/2014/04/how-is-you-wealth-manager-talking-to.html

Let’s get our terms straight here, to start. “Risk” = known probability of an outcome. “Uncertainty” = unknown probability. Investing is always uncertainity – not “risk.”. Our industry falsely labels it as risk implying known outcomes when their are none.

In fact, what the human brain fears is probability of losses and uncertainty. Our brains, and all animals’, aren’t risk averse but uncertainty averse. By definition, all brains are experts at managing risk or known probabilities.

I enjoyed reading your post. It always kills me to see questionnaires where willingness and capacity are mixed. I would say that one other weakness of questionnaires is that the science is lacking as it pertains to linking a questionnaire score to an actual portfolio allocation.

What this points out is that investment planning and financial planning can’t be separated. Without a financial plan you can’t know the required rate of return and related needs such as Betty’s withdrawal requirement. Good luck to the Robo Advisors on this score.

Seems I’m late to this debate. What a good one and so refreshing to find people talking about the distinctions between all aspects of risk. We’ve been using Finametrica since 2000 (from memory) and enjoy not only the quality of the risk tolerance testing material but also the data about the 11 model portfolios (100% cash to 100% equities and everything in between). The historical performance and volatility of all 11 has been tracked over all 10 years rolling periods since January 1973 for New Zealand. The material helps clients understand risk and return issues in relation to the kind of return they’re typically accustomed to – the “bank”. And, by the way, I’m not on the payroll. At my firm, we discuss risk tolerance, risk capacity and risk(return) required in client IPSs. We make an overall risk assessment (not a numeric score) which we match to an asset allocation. If capacity is high but tolerance low with a new investor, we always start them on “trainer wheels” – low risk. That way, their first experiences have less chance of putting them off being diversified and retreating back to the bank. We ignore risk tolerance scores for trustees. They do the test so we know what we’re dealing with. Their personal views are fascinating but must be set aside when they act as trustees. Risk capacity and risk (return) required are the determinants for trusts, estates etc.