Executive Summary

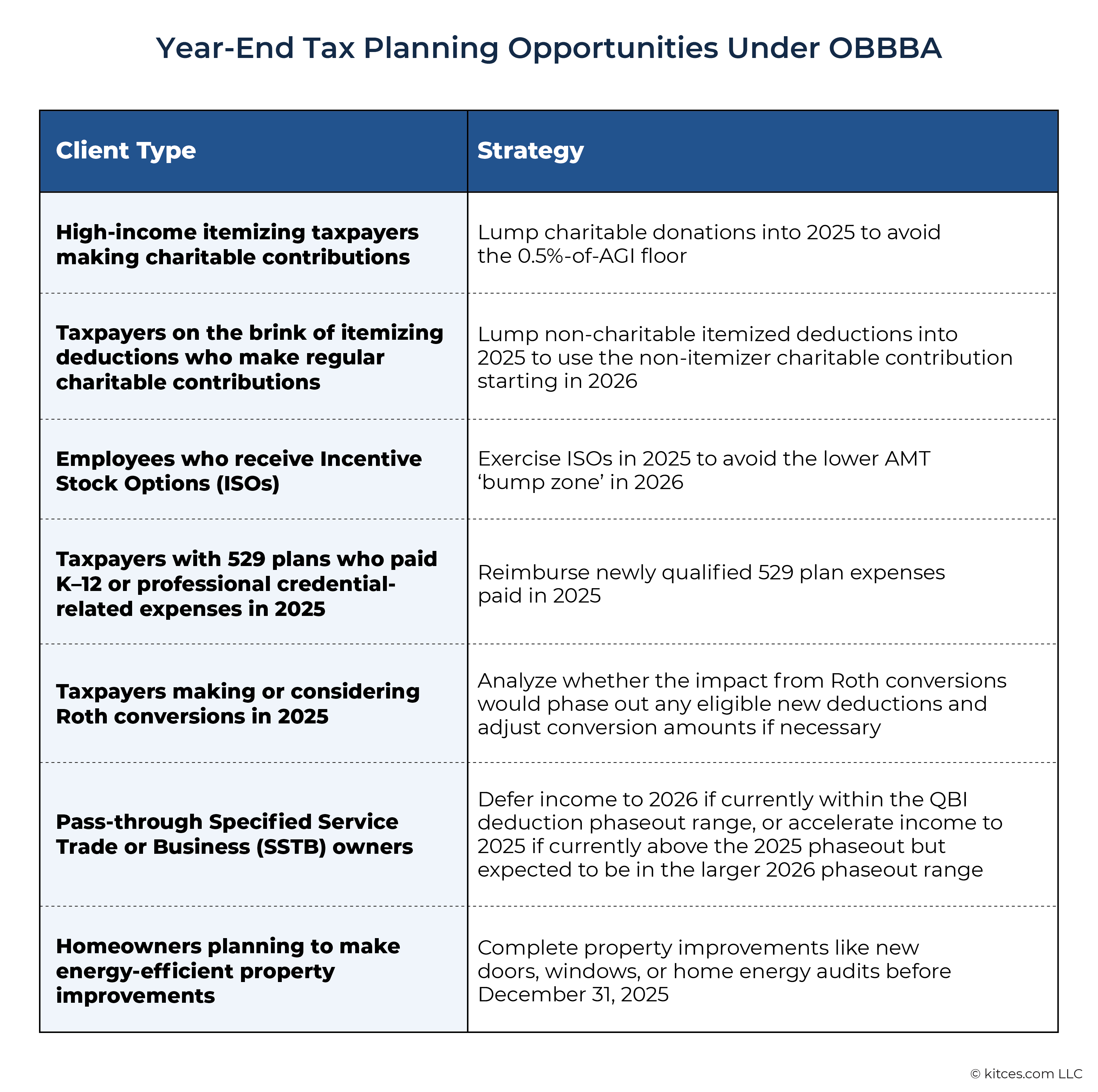

The One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA), signed into law on July 4, 2025, largely serves to extend and modestly expand several provisions of the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), providing advisors and their clients with a clearer tax planning landscape heading into 2026. While many of the most impactful provisions – such as the enhanced State And Local Tax (SALT) deduction and new below-the-line deductions for tips and overtime – are already in effect for 2025, OBBBA still introduces several nuanced planning opportunities with looming year-end deadlines, offering advisors an opportunity to help a variety of clients before the end of 2025.

One major opportunity stems from OBBBA's changes to charitable contribution rules. Beginning in 2026, itemized charitable deductions will be reduced by a 0.5%-of-AGI floor, and high-income taxpayers in the 37% bracket will also see a 2/37 haircut on all itemized deductions. High-income clients may benefit from frontloading charitable giving into 2025 to avoid these new limitations, potentially using Donor Advised Funds (DAFs) to preserve flexibility in future grantmaking. Simultaneously, starting in 2026, a new above-the-line charitable deduction of up to $1,000 (single) or $2,000 (joint) will become available to non-itemizers. This introduces a planning wrinkle for clients near the itemizing threshold, who may want to lump non-charitable deductions like SALT and mortgage interest into 2025, while preserving smaller charitable gifts for future standard-deduction years.

Another time-sensitive strategy applies to employees with Incentive Stock Option (ISOs) compensation. In 2026, the phaseout threshold for the AMT exemption will drop, while the SALT deduction cap will rise to $40,000, increasing the risk of triggering AMT for ISO exercises. This narrows the window for clients with unexercised ISOs to act in 2025 to avoid or reduce AMT exposure. Especially for clients whose ISO exercises would land them in the 2026 "bump zone" – where marginal tax rates on additional AMT income can reach 42% – it may make sense to accelerate exercises into 2025, where they may result in no or lower AMT.

OBBBA also expands 529 plan distribution rules to include up to $20,000 of K–12-related expenses and credentialing costs like coursework required for CFP certification, effective for distributions made after July 4, 2025. Importantly, funds can be used to reimburse expenses incurred at any point during 2025, as long as the distribution is made before year-end. This creates a one-time opportunity for clients with eligible 529 balances to reimburse themselves for previously ineligible educational expenses from earlier in the year.

Additionally, the introduction of several temporary below-the-line deductions for seniors, tip earners, overtime workers, and auto loan interest creates a new layer of complexity for Roth conversion and withdrawal strategies between 2025 and 2028. Each deduction phases out over specific (but separate) income thresholds, meaning pre-tax income from withdrawals or conversions could unintentionally reduce or eliminate one or more deductions. Advisors can revisit existing Roth conversion plans in light of these phaseouts, recognizing that even modest conversions may produce ‘magnified' marginal rates due to lost deductions. Effective coordination between tax software and the advisor's planning tools will be critical to model the true cost of conversions during this window.

For self-employed professionals in Specified Service Trades or Businesses (SSTBs) – including financial advisors – the shifting phaseout ranges for the Qualified Business Income (QBI) deduction create yet another one-time planning opportunity. Though OBBBA retains most of the QBI deduction in its previous form under TCJA, it widens the SSTB phaseout range in 2026. As a result, SSTB owners whose income falls within the current 2025 phaseout range may want to defer income into 2026, where the spike in marginal tax rates on income through the phaseout range will be more gradual. Conversely, those whose income already exceeds the 2025 phaseout limits but could fall within the expanded 2026 range may benefit from accelerating income into 2025 to avoid a spike in marginal income next year.

Finally, OBBBA accelerates the expiration of certain energy credits originally introduced by the Inflation Reduction Act. While some deadlines – such as those for electric vehicle credits – have already passed, there's still time before December 31, 2025, to complete qualifying energy-efficient home improvements and receive up to $3,200 in tax credits. Smaller projects like new doors or windows – and even scheduling a home energy audit – may still be feasible within this narrow timeframe and can help clients reduce both their taxes and utility costs.

Ultimately, while OBBBA doesn't completely overhaul the tax code, it does introduce a series of narrow but meaningful planning opportunities for a wide range of clients. Helping clients plan and execute year-end tax strategies is an annual opportunity for advisors to show their value, but with OBBBA's new provisions, advisors have the chance to create even more tangible tax savings before the calendar flips to 2026!

The "One Big Beautiful Bill Act" (OBBBA) that was enacted on July 4, 2025, is a sprawling piece of tax legislation covering numerous areas of the tax code. However, for all its size, the new law wasn't tremendously impactful from a planning standpoint. Much of it simply extends or modestly expands provisions from the 2017 Tax Cut And Jobs Act (TCJA) that was set to expire at the end of 2025. Many of the most impactful provisions – such as the increased deduction for State And Local Taxes (SALT) and new deductions for qualified tips and overtime wages – are already in effect for 2025. Which means that, other than to provide some certainty that the tax system isn't going to revert to its pre-2017 form, OBBBA itself doesn't present many broadly applicable planning opportunities for most individuals and families going into 2026.

However, for several specific groups – many of which will include clients of financial advisors – some changes set to take effect in 2026 could have a material impact on their tax situation. So it makes sense for advisors to understand where those planning opportunities lie as they ramp up their end-of-year planning for 2025 – and to have conversations with clients while there's still time to implement these strategies before the year comes to a close!

Make Charitable Contributions In 2025 To Avoid The New 0.5%-Of-AGI Floor

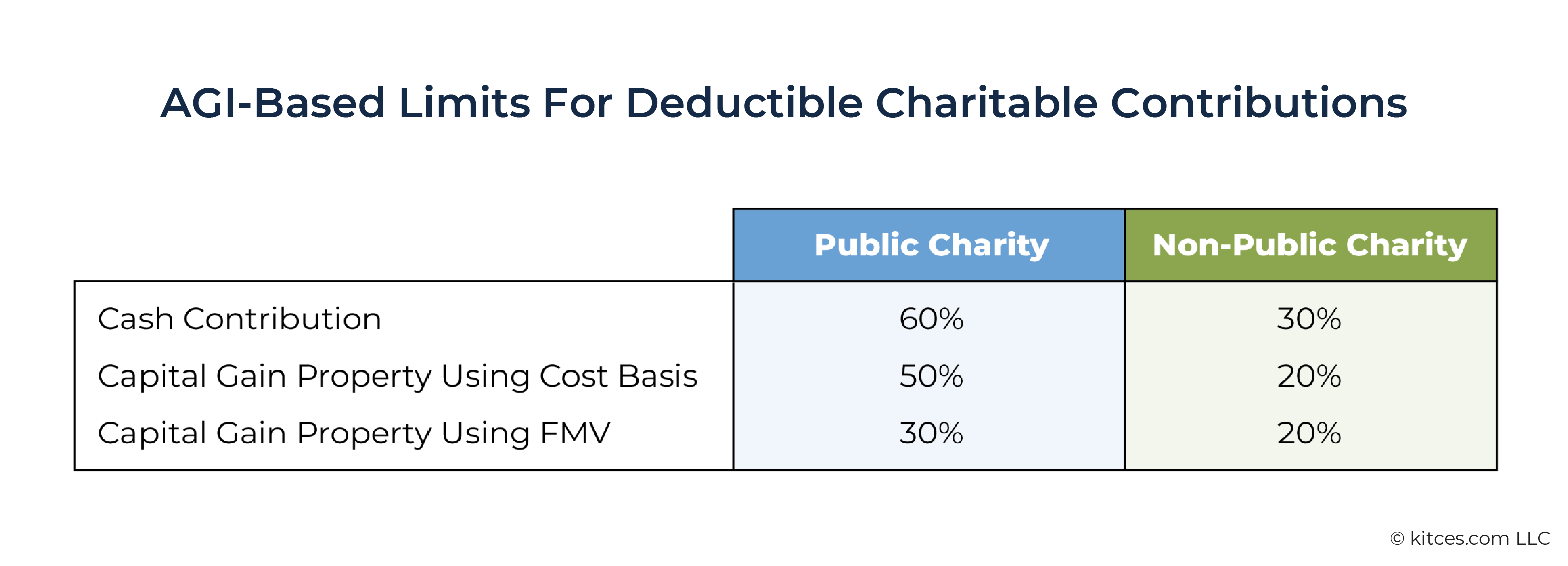

OBBBA made some notable changes to the deductibility of charitable contributions, which have up until now been fully deductible for taxpayers who itemize deductions - although they are subject to maximum deductibility limits ranging from 20% - 60% of AGI, depending on whether the contribution is made to a public or non-public charitable organization, whether the donation is in cash or other types of property, and whether the value of the donation is calculated using the donor's cost basis or the property's fair market value.

One of the changes created a new ‘floor' of 0.5% of Adjusted Gross Income (AGI) for charitable contributions that can be taken as itemized deductions on Schedule A. This means that taxpayers who itemize their deductions must first subtract 0.5% of their AGI from their qualifying charitable contributions, and that the total amount of contributions must exceed 0.5% of AGI to be deductible at all.

For example, taxpayers with $100,000 of AGI can only deduct contributions above $100,000 × 0.5% = $500, those with $200,000 of AGI can only deduct contributions above $1,000, and so on. The rule kicks in beginning in 2026, meaning that contributions made in 2025 will still be fully deductible (assuming that the taxpayer already itemizes their deductions).

On top of directly reducing charitable deductions by 0.5% of AGI, OBBBA also introduced a new reduction starting in 2026 to overall itemized deductions for taxpayers in the 37% Federal tax bracket. For those taxpayers, their total itemized deductions will be reduced by 2/37 – effectively reducing the amount of tax savings realized for every dollar of itemized deductions from $0.37 to $0.35. The overall itemized deduction limit is taken after the 0.5%-of-AGI floor on itemized charitable contributions, meaning that starting in 2026, charitable contributions made by taxpayers in the 37% bracket will be reduced first by 0.5% of their AGI, and then further reduced by the 2/37 reduction on overall itemized deductions.

Example 1: Bernice is a single taxpayer with $750,000 of Adjusted Gross Income (AGI), who is in the 37% Federal marginal tax bracket. She plans to make a $75,000 contribution to her alma mater in honor of her 40th class reunion in 2026.

If Bernice makes the contribution in 2026, it would be reduced by the 0.5%-of-AGI floor on charitable deductions, and then by the 2/37 reduction for all itemized deductions for taxpayers in the 37% tax bracket. For the first part of the calculation, the $75,000 contribution would be reduced by 0.5% × $75,000 = $3,750 to $71,250. Then that amount would be reduced by 2/37 to $71,250 − (2/37 × $71,250) = $67,399.

For high-earning taxpayers, particularly those in the 37% tax bracket, the best strategy might be to make charitable contributions in 2025 that would have otherwise happened in 2026 or later. This has the benefit of avoiding both the 0.5%-of-AGI floor on itemized charitable deductions and the 2/37 reduction of overall itemized deductions that take effect in 2026: a charitable contribution made in 2025 would be fully deductible (as long as it falls below the existing AGI-based deductibility limits shown above).

Example 2: Bernice from Example 1 decides to make the contribution to her alma mater in 2025 instead of waiting until 2026.

In this case, she'll be able to deduct the full $75,000 contribution rather than having its deductibility reduced to $67,399. In terms of actual taxes saved, Bernice's contribution would be worth $75,000 × 0.37 = $27,750 if made in 2025, and $67,399 × 0.37 = $24,938 if made in 2026.

Thus, making the contribution in 2025 rather than 2026 would result in total tax savings of $2,812.

If an individual wanted to make a charitable contribution in 2025 to get the full tax benefit of the contribution, while waiting until 2026 or later to actually disburse the funds to charitable organizations, they could contribute to a Donor Advised Fund (DAF). This would allow the taxpayer to receive a deduction in the year they contribute to the DAF while the contributed funds can remain in the DAF indefinitely until the donor decides to distribute them to a qualified charitable organization. In this way, a higher-income donor could effectively ‘book' several years' worth of charitable contributions in 2025 while getting the full tax benefits of those contributions, rather than waiting to make them until future years when they'll be subject to reductions.

Lump Other Deductions Into 2025 To Use The New Non-Itemizer Deduction

In addition to the 0.5%-of-AGI floor on itemized charitable contributions, OBBBA's other big change to the contribution rules is the creation of a new charitable deduction available only to taxpayers who do not itemize deductions, also beginning in 2026. This new charitable deduction is not subject to the 0.5%-of-AGI floor that applies to itemized contributions.

The new charitable deduction for non-itemizers has the biggest implications for taxpayers who aren't in the highest tax brackets and who are less likely to regularly itemize their deductions. For example, a person who rents their home and pays little or no state tax might never itemize their deductions, while a family whose mortgage and deductible State and Local Tax (SALT) payments aren't quite enough to exceed the standard deduction might only itemize deductions in years when their other deductible expenses like medical expenses or charitable contributions are high enough to push their total itemized deductions higher than the standard deduction. In either case, the new "non-itemizer" charitable deduction allows taxpayers with charitable contributions to deduct at least some of those contributions regardless of whether they itemize their deductions in that year.

Under OBBBA, taxpayers who take the standard deduction can deduct up to an additional $1,000 (for single filers) or $2,000 (for joint filers) of cash charitable contributions starting in 2026. As noted before, this deduction is not subject to the 0.5%-of-AGI floor that impacts deductible charitable contributions for those who itemize; rather, it's only available to those who take the standard deduction.

For taxpayers who rarely or never itemize, the new rule might offer their first opportunity to deduct charitable contributions, previously available only to taxpayers who itemize (other than in 2020 and 2021, when Congress's COVID relief legislation created a temporary non-itemizer charitable deduction of $300 for single filers and $600 for joint filers). While taxpayers will need to wait until the 2026 tax year to start claiming the deduction, advisors can remind these individuals to start tracking and documenting contributions after the new year so they'll be ready to claim the deduction when they file their 2026 tax returns.

But for taxpayers on the brink of itemizing (but who don't necessarily itemize every year), there's a new choice to make. Should they itemize and have charitable contributions subject to the 0.5%-of-AGI floor, or take the standard deduction and use the non-itemizer charitable deduction?

Since the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) went into effect, it's been a common strategy for taxpayers regularly on the brink of itemizing to ‘lump' their payments of certain deductible expenses – like state or property tax payments and charitable contributions – together into a single year. This allows them to exceed the standard deduction in some years to get the full tax benefit of the excess deductions, then revert to the standard deduction in other years. Charitable contributions have often been a key part of that strategy, as they're one of the few deductible expenses taxpayers can fully control in both amount and timing.

Under the traditional deduction lumping strategy, a taxpayer might concentrate two to three years' (or more) worth of charitable contributions into a single year, either as direct donations or as contributions to a Donor Advised Fund (DAF). They would then make no further deductible contributions for several years while taking the standard deduction until they're ready to have another ‘lumping' (and itemizing) year.

But with the new charitable deduction for non-itemizers, taxpayers don't necessarily need to lump all of their contributions into one year to get their full tax benefit. And in fact, because the non-itemizer charitable deduction isn't subject to the 0.5%-of-AGI floor, it might be more beneficial to make charitable contributions in non-itemizing years, at least up to the $1,000 (single) or $2,000 (MFJ) limits.

For 2025, then, it may make sense to consider this a potential ‘lumping' year in which a taxpayer times as many of their deductible expenses as possible (e.g., medical expenses, SALT payments up to $40,000 under OBBBA's increased deduction limit, mortgage interest, charitable contributions, and casualty and theft losses) to fall within the same tax year to enable them to itemize their deductions. At the same time, taxpayers might consider reserving some of those charitable contributions – at least those that would be made in cash (and not, for example, personal property or securities, or DAF contributions) – to contribute and deduct them in years when taking the standard deduction in order to get the full benefit from the newly available Form 1040 charitable deduction.

Exercise Incentive Stock Options (ISOs) To Avoid The Lower 2026 AMT ‘Bump Zone'

Most taxpayers are not subject to the Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT), but certain groups are more susceptible to AMT exposure than others. One such group includes employees with equity compensation in the form of Incentive Stock Options (ISOs). When an employee exercises an ISO to buy their employer's stock, the price they pay for the stock is usually less than the stock's market value. The difference between the two – known as the ‘bargain element' of the ISO exercise – is excluded from income for regular income tax purposes, but included for AMT purposes. A large ISO exercise can therefore trigger AMT if it pushes the taxpayer's AMT income high enough that their tax as calculated by the AMT method is higher than their regular Federal income tax.

Since 2018, under the Tax Cut and Jobs Act (TCJA), AMT exposure has been relatively rare even among ISO recipients, mainly due to three factors. First, TCJA increased the AMT exemption (i.e., the amount subtracted from AMT income in lieu of the standard or most itemized deductions), which is now up to $88,100 (S) or $137,000 (MFJ) in 2025, meaning that most taxpayers now need to have much higher AMT income than regular income to trigger AMT. Second, TCJA also increased the income threshold where the AMT exemption begins to phase out, which now starts at $626,350 (S) / $1,252,700 (MFJ) in 2025, giving all but the very highest income households use of the full exemption. And third, TCJA imposed a $10,000 limit on the State and Local Tax (SALT) deduction (which is also added back to income for AMT purposes), meaning that people who pay high state and local taxes would only add a maximum of $10,000 back to their AMT income. With a higher AMT exemption, the ability to use the AMT exemption at higher income levels, and a lower SALT deduction to add back to AMT income, it would take an ISO exercise with a total ‘bargain element' of at least $40,000 – and in many cases upwards of $100,000 – to result in AMT exposure.

Under OBBBA, two of these three factors will change in ways that could expose more taxpayers to AMT. While the AMT exemption itself remains unchanged, the exemption phaseout thresholds will be reduced to $500,000 (single) or $1 million (MFJ) in 2026, which will mean more households will have their AMT exemption either partially or entirely phased out. Additionally, the SALT deduction will increase to a maximum of $40,000 starting in 2025, increasing the amount that can be added back to AMT income for those who pay high state and local taxes.

Taken together, these factors won't necessarily result in a surge of new taxpayers being exposed to AMT across the board. The AMT exemption and phaseout levels are still high enough to require a significant amount of AMT adjustments before the tax applies. But for those who already have significant AMT adjustments – such as from exercising ISOs – the new rules could be enough to put them over the threshold into AMT, which could make it better to exercise ISOs in 2025 instead of waiting until 2026.

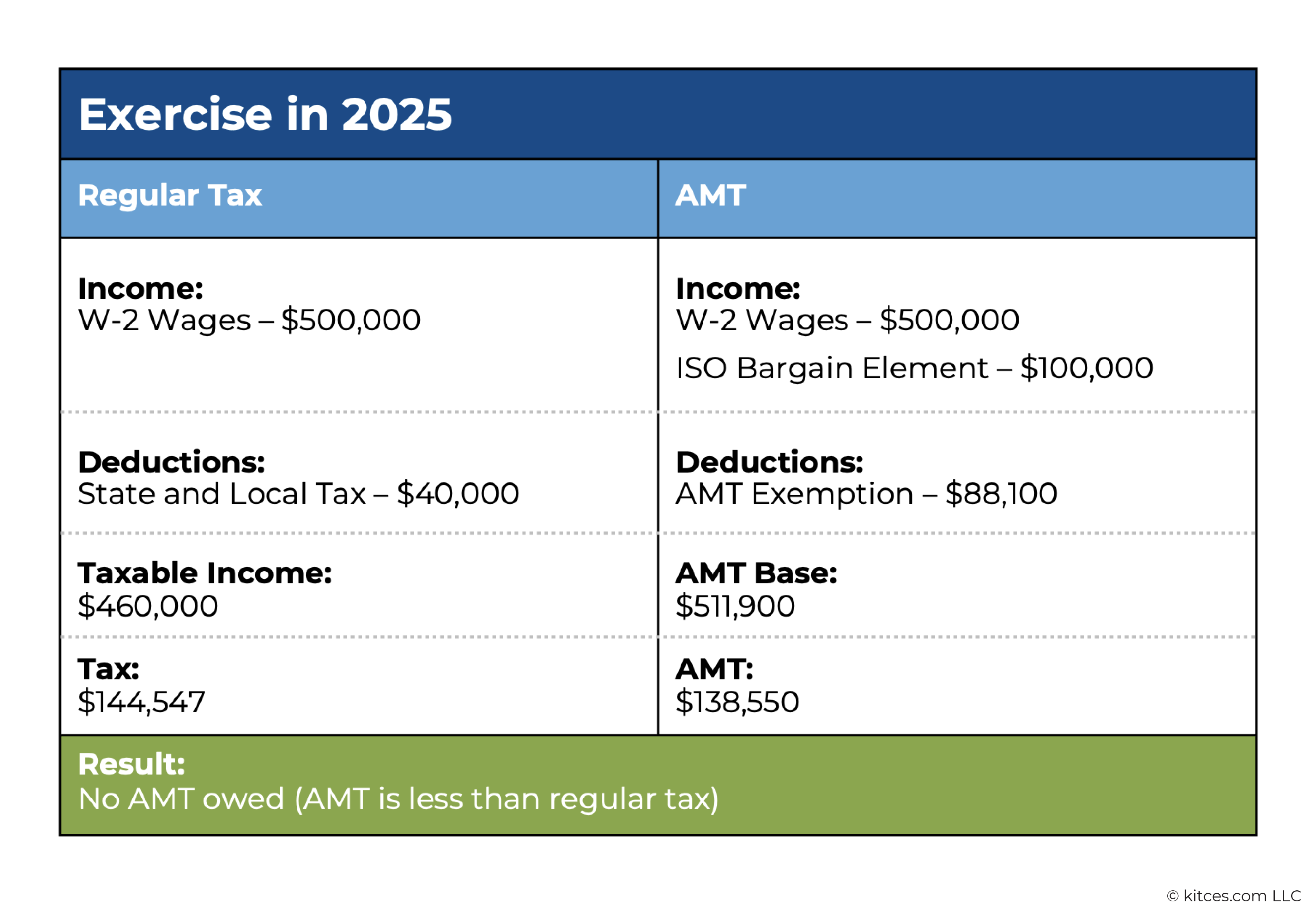

Example 3: Maia is a single tax filer living in California who works for a large tech startup. Her W-2 wages are $500,000 per year, and she pays more than $40,000 of state and local taxes each year.

Maia has unexercised Incentive Stock Options (ISOs) which, if exercised, would have a bargain element of $100,000.

If Maia exercises the ISOs in 2025, her regular taxable income would equal $500,000 (her W-2 wages) − $40,000 (her state and local tax deduction) = $460,000.

For AMT purposes, Maia's AMT income would be $460,000 (her regular taxable income) + $40,000 (the SALT deduction) + $100,000 (the bargain element on the ISOs) = $600,000. Because this is under the current AMT exemption phaseout threshold of $626,350, Maia can use the full $88,100 AMT exemption. As shown below, exercising the ISOs in 2025 would result in no AMT:

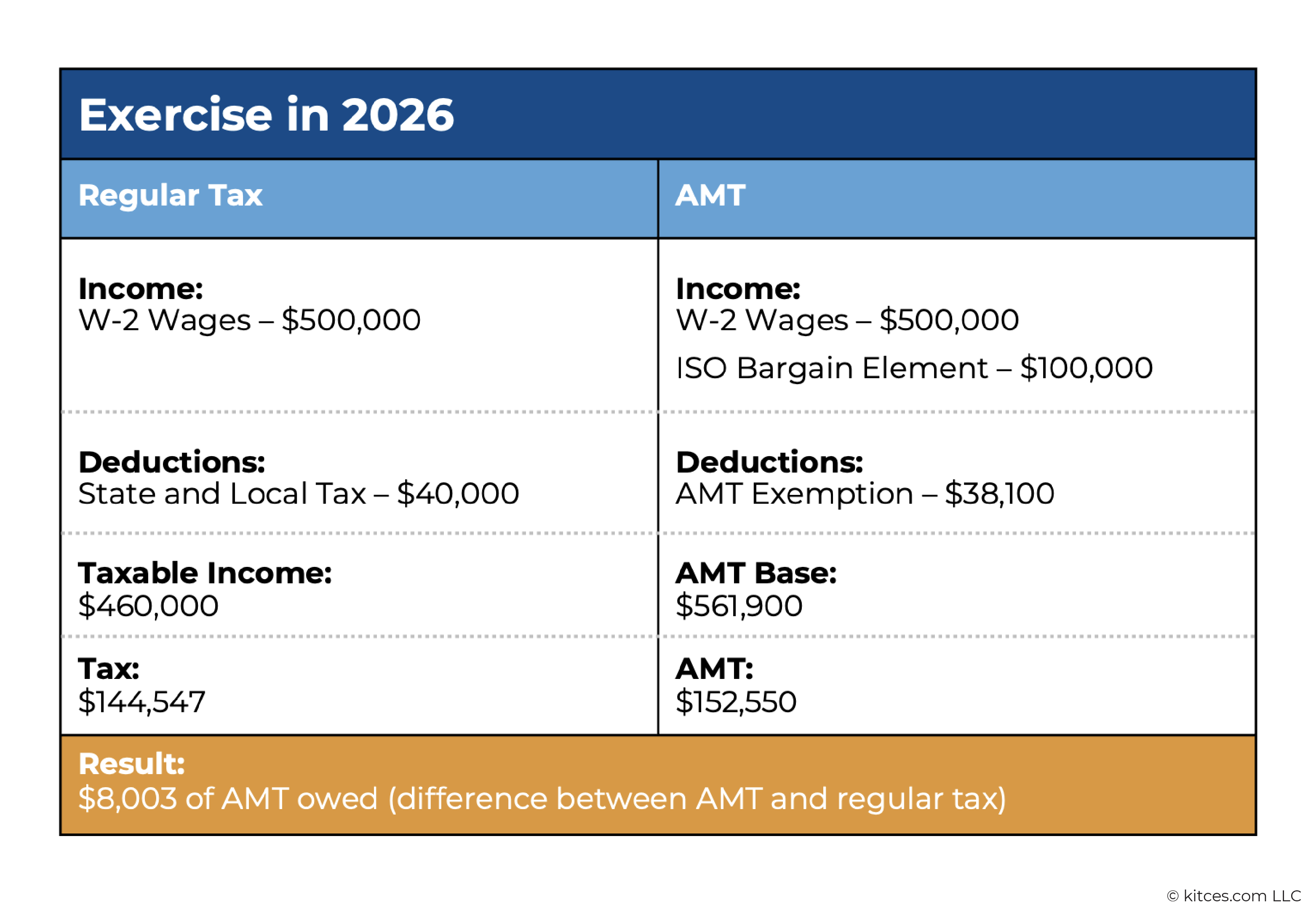

If Maia exercises her ISOs in 2026, her regular taxable income and AMT income will be the same. However, because the AMT exemption phaseout threshold is reduced to $500,000 in 2026, Maia's exemption will be reduced by 50% of the excess of her AMT income over the threshold. As a result, her AMT exemption would be $88,100 – (50% × ($600,000 − $500,000)) = $38,100. This results in owing $8,003 as AMT, as shown below:

In other words, exercising the ISOs in 2025 instead of 2026 would save Maia $8,003 in AMT, entirely on account of the lower AMT exemption threshold under OBBBA.

There are cases where it would make more sense to exercise ISOs in 2025 even if doing so results in paying AMT for 2025. If exercising the ISOs in 2026 would result in AMT income above the new 2026 AMT exemption phaseout thresholds of $500,000 (S) / $1,000,000 (MFJ), the employee would likely pay less AMT if they exercise the ISOs in 2025 instead. This is because of the ‘bump zone' in marginal tax rates created by the AMT exemption phaseout: once AMT income exceeds the phaseout threshold, the exemption is decreased by 50% of the excess, creating $1.50 of AMT exposure for every dollar earned above the threshold. Which means that income earned in the phaseout range is taxed at 150% of the nominal AMT rate of 28%, or 1.5 × 28% = 42%.

Employees may be able to avoid incurring AMT income in that ‘bump zone' by exercising their ISOs in 2025 rather than 2026.

Example 4: Evelyn is a single taxpayer with $400,000 of W-2 wages. She has no deductible state or local taxes and takes the standard deduction.

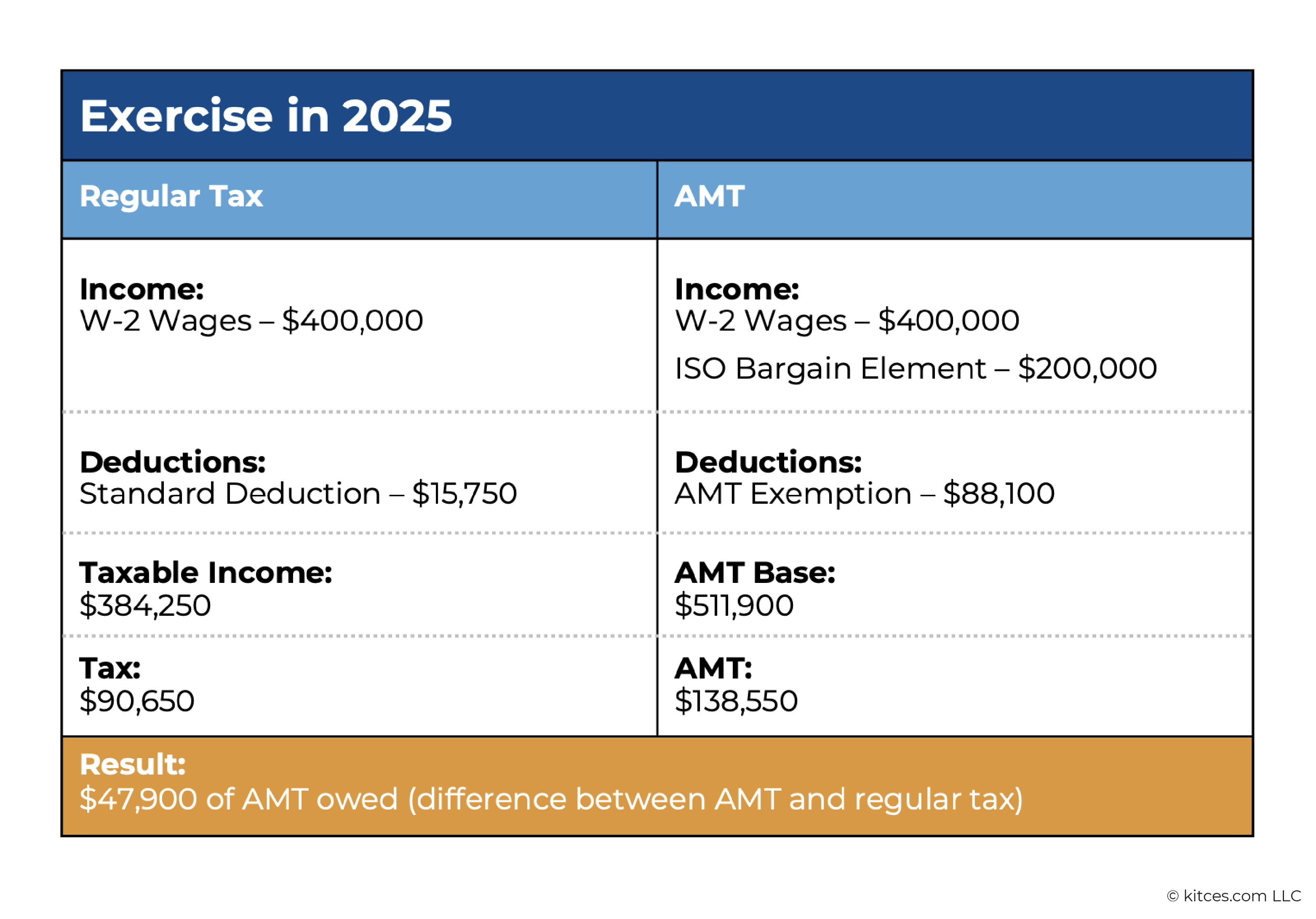

Evelyn has unexercised ISOs with a bargain element of $200,000. As shown below, If she exercises the options in 2025, she will have regular taxable income of $400,000 (her W-2 wages) − $15,750 (the standard deduction) = $384,250; and AMT income of $384,250 (her regular taxable income) + $15,750 (the standard deduction) + $200,000 (the bargain element of the ISOs) = $600,000. Her AMT income is below the phaseout threshold for the AMT exemption, so she will still have the entire $88,100 AMT exemption. However, because of the size of the AMT adjustment created by the ISO bargain element, Evelyn will owe $47,900 in AMT if she exercises the ISOs in 2025.

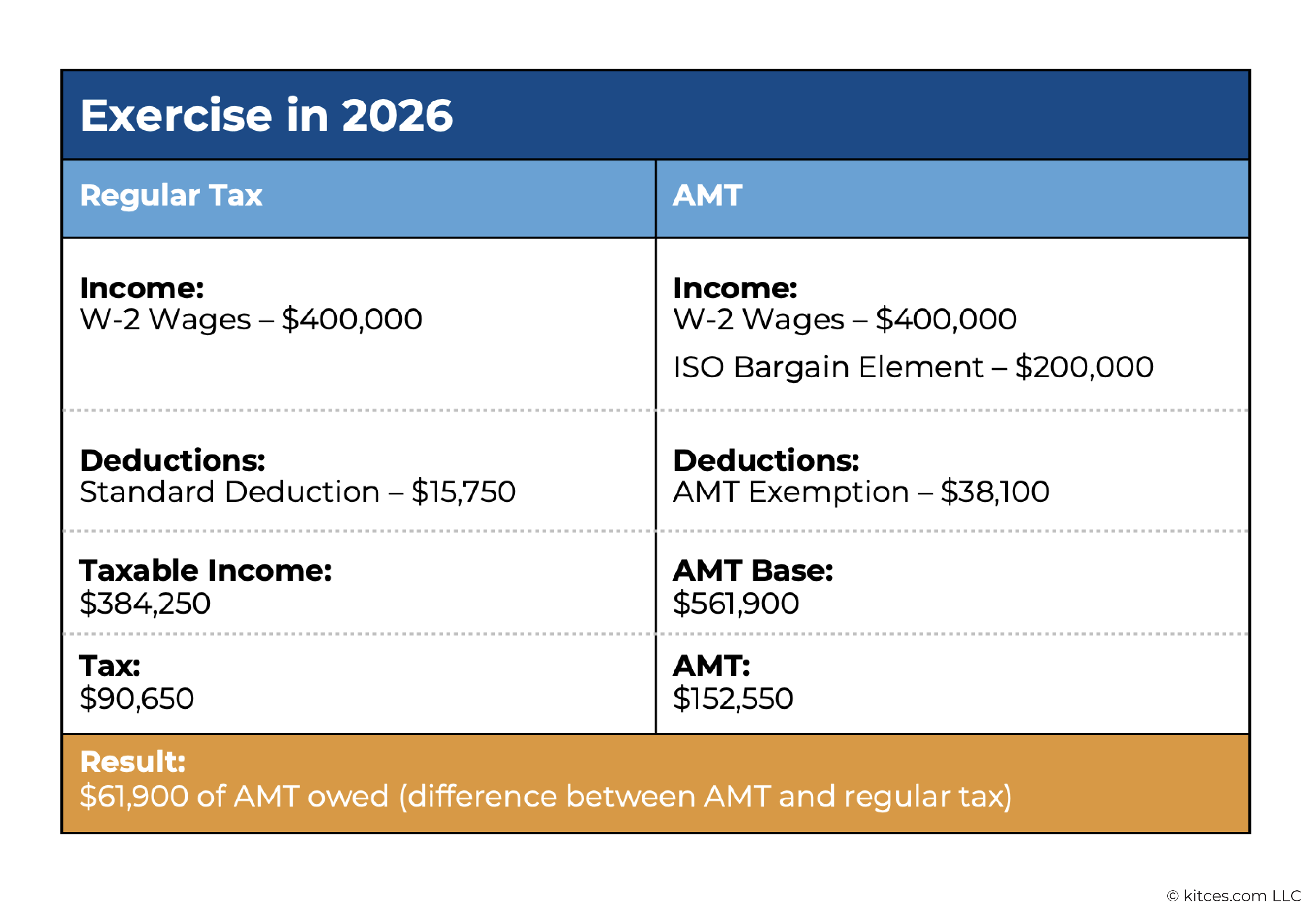

If Evelyn exercises the ISOs in 2026, her AMT income will still be $600,000, but that will be above the new 2026 AMT exemption phaseout threshold of $500,000. Evelyn's AMT exemption will be reduced by 50% of her AMT income above the threshold, to $88,100 – 50% × ($600,000 − $500,000) = $38,100. As a result, Evelyn will owe $152,550 in AMT if she exercises her ISOs in 2026.

In other words, even though Evelyn would owe AMT regardless of whether she exercises her ISOs in 2025 or 2026, the amount of AMT varies greatly depending on the timing of the exercise. If she exercises the ISOs in 2025, Evelyn would owe $47,900 in AMT, while if she exercises in 2026, she would owe $61,900 in AMT – a whopping $14,000 difference depending solely on whether she exercises her ISOs in 2025 or 2026!

For clients with unexercised ISOs, the key question is whether it's better to exercise those options in 2025 or wait until 2026 or later, after the new phaseout thresholds take effect.

For some clients, it may not matter whether their ISOs are exercised in 2025 or 2026. For example, if the total bargain element of the ISO isn't big enough to trigger AMT in either year, there's no difference from a tax standpoint between exercising in 2025 or 2026.

But for those whose ISO exercise wouldn't trigger AMT in 2025 but would in 2026 (especially when combined with the new higher SALT cap), exercising in 2025 could help avoid an AMT bill.

Perhaps even more crucial is determining whether exercising ISOs would cause the client's AMT income to rise above the AMT exemption phaseout threshold – and into the 42% marginal rate ‘bump zone' – if the options are exercised in 2026. In that case, it could be worth exercising the ISOs in 2025 even if doing so triggers AMT, to avoid owing even more AMT by exercising the options later.

It's worth remembering that paying AMT on an ISO exercise creates an AMT credit, which can offset regular tax in future years to the extent that the taxpayer's regular tax exceeds AMT. For clients who receive ISO grants only sporadically or on a one-time basis, paying AMT in one year isn't necessarily a problem if they'll eventually recover it through the AMT credit. However, they'll still need the funds to pay the AMT bill upfront, since it only applies to ISOs that are exercised and held rather than sold immediately. (Clients could consider selling some of the underlying shares after exercise to pay the AMT bill, but would need to remember that doing so creates a disqualifying disposition that negates the beneficial tax treatment of the ISOs.)

Reimburse Newly Eligible 529 Plan Expenses Incurred During 2025

OBBBA added two new categories of expenses that can be paid tax-free from 529 plans. The first allows up to $20,000 per year of K–12-related expenses, including tuition, curriculum materials, standardized testing fees, postsecondary enrollment, outside tutoring, and educational therapies – an expansion of the previous rule that permitted up to $10,000 of K-12 tuition only.

The second category covers expenses related to obtaining or maintaining a qualified postsecondary credential, including tuition and fees for classes, books and other materials, testing fees, and continuing education expenses. Eligible programs include any industry-recognized credential – including the CFP certification – as well as apprenticeship programs and required occupational licenses.

OBBBA provides that these new rules are effective for any 529 plan distributions made after the law's enactment date of July 4, 2025. And according to the rules of 529 plans, funds may be distributed to pay or reimburse any qualified expense incurred within the same tax year as the distribution.

Putting these rules together, it's apparent that distributions can be made from a 529 plan for any qualified expense incurred during 2025 – including those in the new expense categories created by OBBBA – even if the expense itself was incurred before the law's July 4 enactment date. Regardless of when the expense itself was incurred, the distribution to reimburse that expense must have been made on or after July 5, 2025.

Example 5: Brianna, an aspiring CFP certificant, enrolled in an educational program on March 1, 2025 to prepare for the CFP exam. On July 10, 2025, after OBBBA took effect, Brianna took a distribution from her 529 plan to reimburse herself for the cost of enrolling in the program.

Even though the educational program falls under the new category of postsecondary credentials created by OBBBA and was taken before OBBBA itself was enacted, the distribution presumably qualifies for tax-free treatment, because 1) the distribution to pay for the program was made in the same calendar year that the expense was incurred; and 2) the distribution was made after OBBBA's enactment date of July 4, 2025.

For clients with unused 529 plan funds who don't anticipate needing them for future education costs, it may be worth considering a distribution to reimburse qualified educational expenses incurred in 2025, including those newly allowed under OBBBA. The distribution would need to be made by the end of the year, however, in order to be a qualified distribution for any expenses incurred in 2025.

Other ways to benefit from the tax-free status of 529 plan assets include designating a new beneficiary who is more likely to use the funds, rolling the 529 plan funds into a Roth IRA (but only after the account has been open for at least 15 years), or rolling the funds into a 529A ABLE account (if the beneficiary qualifies based on disability). But if the goal is simply to free the money from the 529 plan's distribution restrictions, reimbursing qualified expenses may be the most straightforward approach.

Adjust Pre-Tax Withdrawals And Roth Conversions To Preserve Deductions In 2026-2028

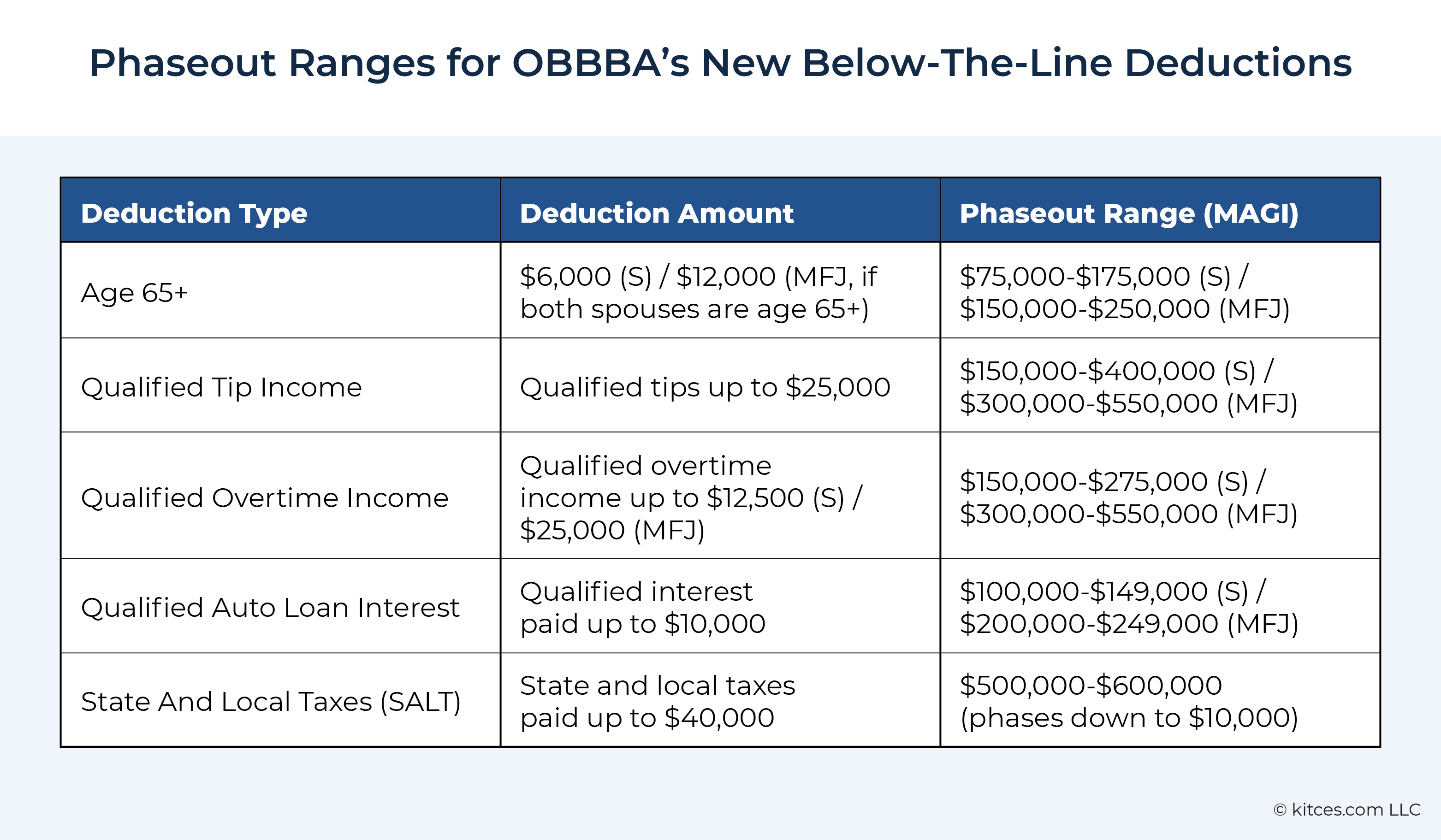

One of the most high profile changes under OBBBA was the creation of several new below-the-line deductions: up to $6,000 for single taxpayers ($12,000 for married couples) age 65 or older, up to $25,000 (for all filing statuses) of qualified tip income, up to $12,500 ($25,000 for couples) of qualified overtime income; and up to $10,000 (for all filing statuses) of qualified auto loan interest. All the new deductions are temporary, effective from 2025 through 2028. OBBBA also raised the amount of State And Local Taxes (SALT) that can be taken as an itemized deduction from $10,000 to $40,000 (increasing 1% until 2029, after which the SALT deduction reverts to $10,000 in 2030).

A household could theoretically qualify for all of OBBBA's new deductions at once – provided they meet each deduction's eligibility requirements – allowing them to significantly reduce their taxable income. However, as shown below, the deductions all phase out at varying levels of Modified Adjusted Gross Income (MAGI) (which in most cases is simply the taxpayer's AGI):

In theory, it's preferable for taxpayers eligible for these deductions to keep their income under the phaseout thresholds to preserve their eligibility. In reality, though, most people don't have much control over when they receive and are taxed on their income (e.g., employees don't usually get to ask their employers to pay them in one year or another solely for tax planning purposes).

However, one group of people do have some flexibility on the timing of their income: Those making distributions (or Roth conversions) from pre-tax retirement accounts. Individuals over age 59 1/2 have full control over how much they distribute from, and therefore are taxed on, their pre-tax accounts after satisfying their own living expenses and any Required Minimum Distributions (RMDs). To the extent that someone has flexibility over the amount they distribute from their pre-tax accounts, it may make sense to adjust those distributions to maximize the value of their OBBBA-related deductions from 2025 through 2028.

For example, if an individual has both pre-tax and Roth funds available to withdraw, they can reduce pre-tax withdrawals (which are included in gross income) and increase Roth withdrawals (which are exempted from gross income) to keep their income below the thresholds for any deductions they may be eligible for.

Example: Kristen and James are a retired couple who are both age 65. They currently have $3 million in pre-tax retirement accounts and $2 million in Roth accounts. Their living expenses (including taxes) are $200,000 per year.

Currently, Kristen and James fund their living expenses solely from their pre-tax retirement accounts. Assuming they have no other income, this gives them an AGI of $200,000.

Under OBBBA, they're eligible for the Age 65+ deduction of up to $12,000 (since they are both age 65). However, their $200,000 of AGI puts them halfway through the deduction's phaseout range of $150,000–$200,000, meaning that they're only eligible for a deduction of 50% × $12,000 = $6,000.

If Kristen and James instead reduced their pre-tax retirement distributions to $150,000 from 2025–2028, and took the remaining $50,000 from their Roth account, their AGI would only be $150,000 – putting them at the bottom of the phaseout range and making them eligible for the full $12,000 deduction.

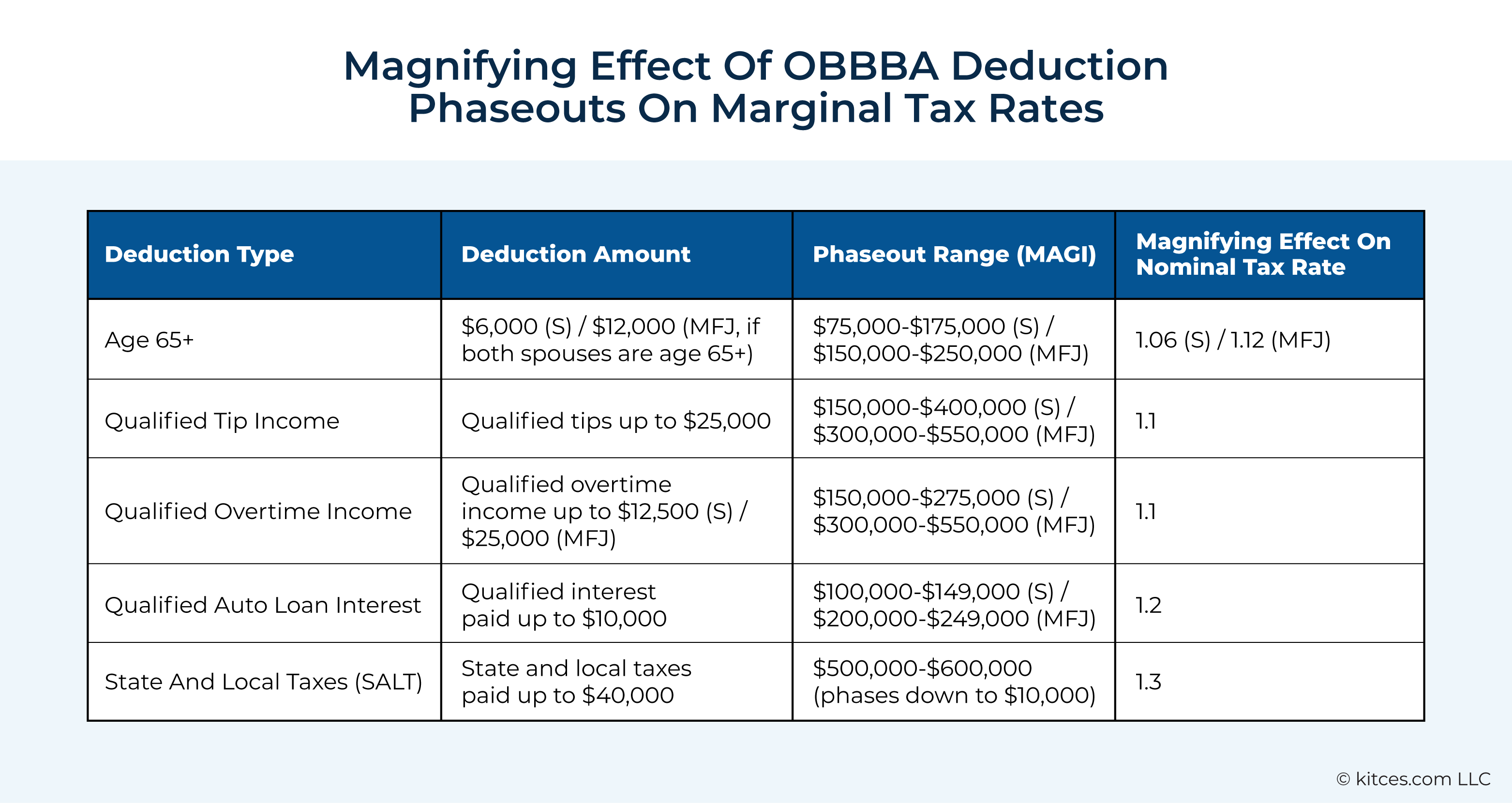

For households making annual Roth conversions, it's also worth considering how additional income may interact with deduction phaseouts. Any Roth conversions that push income into those ranges will have a higher ‘effective' marginal tax rate than the taxpayer's nominal tax bracket, since each dollar of additional gross income (in the form of the Roth conversion) adds more than a dollar of taxable income (because of the lost deductions).

For example, a married couple age 65+ with $150,000 of gross income who adds an extra $100,000 of income would completely phase out the $12,000 age 65+ deduction – in other words, the $100,000 Roth conversion would result in $112,000 of additional taxable income. For a couple in the 22% nominal tax bracket, dollars earned within that phaseout range would have an effective marginal rate of 22% × ($112,000 ÷ $100,000) = 24.64%.

Another way of putting it is that adding income within the phaseout range for each deduction ‘magnifies' the marginal tax rate for that income beyond the taxpayer's nominal bracket. As shown below, the magnifying effect varies by the type of deduction, with the age 65+ deduction for single filers having the lowest impact at 1.06x and the SALT deduction phasedown having the greatest at 1.3x:

Notably, when an individual is eligible for multiple deductions with overlapping phaseout ranges, the effective marginal rate where the ranges overlap will be even higher. For instance, for a married filer who is both age 65+ and has qualified auto loan interest, the phaseout ranges for both deductions overlap between $200,000 and $249,000 of MAGI. In this range, any additional income has an effective marginal rate of 1 + (0.12 + 0.2) = 1.32x the taxpayer's nominal tax bracket. That is, if their nominal bracket is 22%, their effective marginal rate would be 22% × 1.32 = 29.04%.

Similarly, for a married filer with both qualified tip or overtime wages and state and local tax payments, those deduction phaseouts overlap between $500,000 and $550,000 of AGI, meaning that the nominal tax bracket in that range is magnified by up to 1 + (0.1 + 0.3) = 1.4x. So, for a married filer in the 35% tax bracket with $40,000 of SALT payments and $25,000 of qualified tips or overtime, their effective marginal rate in that range would be 35% × 1.4 = 49%.

Ultimately, the point of Roth conversions is to pay tax at a lower rate on the conversion than would be paid if the same dollars were converted or distributed in a later year. To that end, it could still make sense to proceed with conversions – even if doing so would sacrifice some eligibility for new deductions under OBBBA – if the taxpayer's marginal tax rate is expected to be higher in the future.

However, the more a person's current nominal tax rate is ‘magnified' by the loss of deductions today, the higher the bar is set for their future tax rate to surpass in order for the conversion to make economic sense. Therefore, for clients with pre-OBBBA plans to make Roth conversions, it makes sense to re-run the numbers, either through a tax planning program like Holistiplan or FP Alpha or with the assistance of the client's tax professional. If the conversion results in an outsize amount of tax owed relative to the amount converted, it may be prudent to re-evaluate the amount of the conversion – or even pause conversions altogether – for as long as the new deductions remain in effect.

Defer (Or Possibly Accelerate?) Income For Higher-Income SSTB Owners In The QBI Phaseout Range

One provision of OBBBA that came as a relief to owners of pass-through businesses – including sole proprietorships, partnerships, and S-corporations – was the permanent extension of the Section 199A deduction for up to 20% of Qualified Business Income (QBI). The downside, however, was that the new law also preserved the complete phaseout of the Section 199A deduction for higher-income owners of Specified Service Trades or Businesses (SSTBs) like doctors, accountants, attorneys, consultants, and financial advisors.

The one silver lining is that beginning in 2026, OBBBA slightly widens the income range over which the deduction phases out. Which means that for business owners with income within or just above the current phaseout range, deferring that income until 2026 could allow it to be taxed at a lower rate than if it were earned and taxed in 2025.

Under the previous law, SSTB owners begin to lose their Section 199A deduction once their taxable income (before applying the deduction) crosses the ‘applicable threshold' of $197,300 for single filers or $394,600 for joint filers. The deduction phases out over a range of $50,000 (Single)or $100,000 (MFJ) of taxable income above the applicable threshold. For SSTB owners with income above $247,300 (Single) or $494,600 (MFJ), the deduction is eliminated entirely.

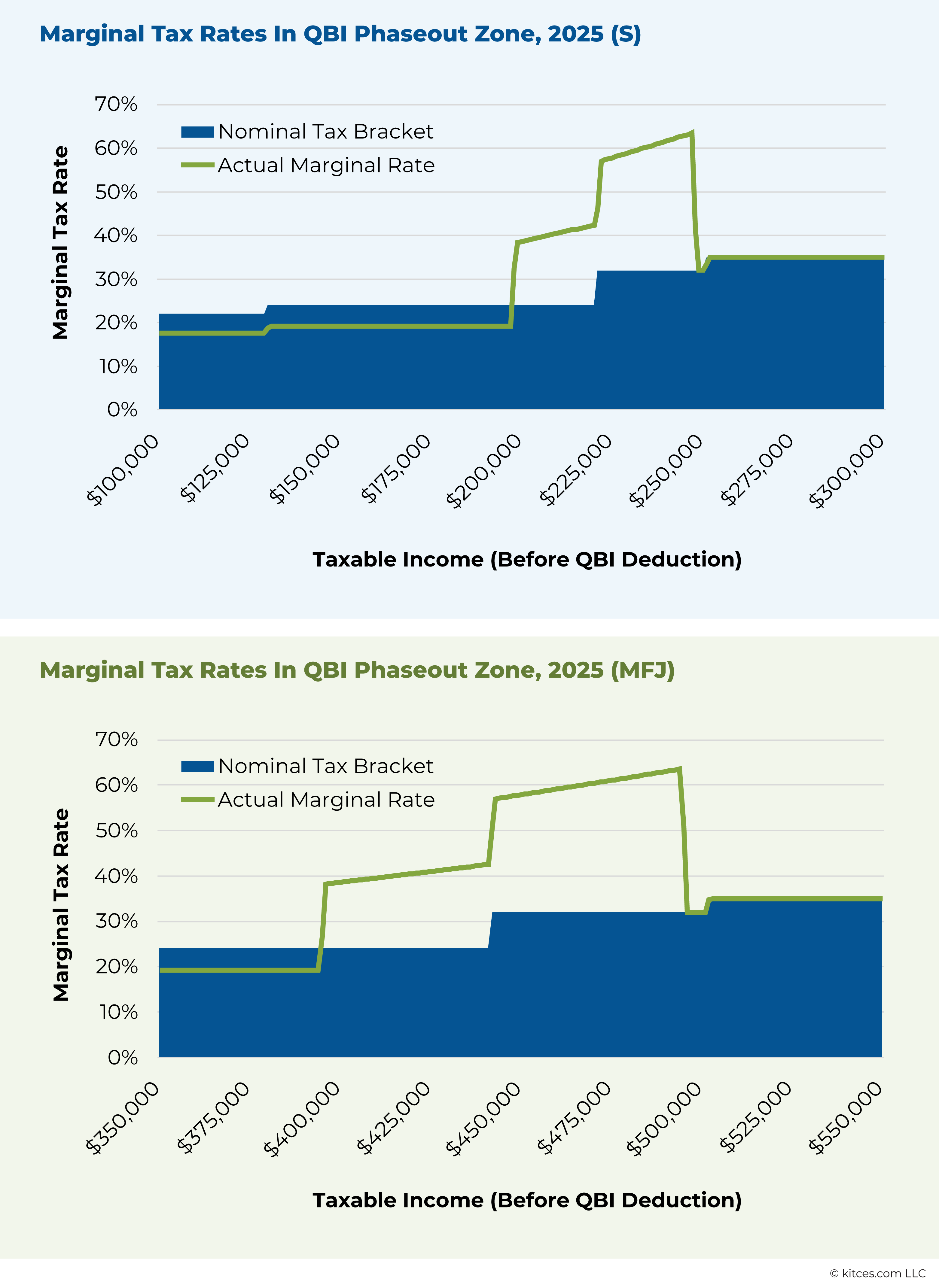

From a tax planning perspective, it's crucial to be aware of the Section 199A phaseout ranges. For SSTB owners whose income falls within them, the marginal tax rate on any additional dollars earned is significantly higher than the owner's nominal Federal tax bracket. As shown below, for those within the threshold range of $197,300–$247,300 for single filers and $394,600–$494,600 for joint filers, the actual marginal tax rate on dollars earned at the bottom of the phaseout range is close to 40% and increases from there, up to more than 60% for dollars earned at the top of the range.

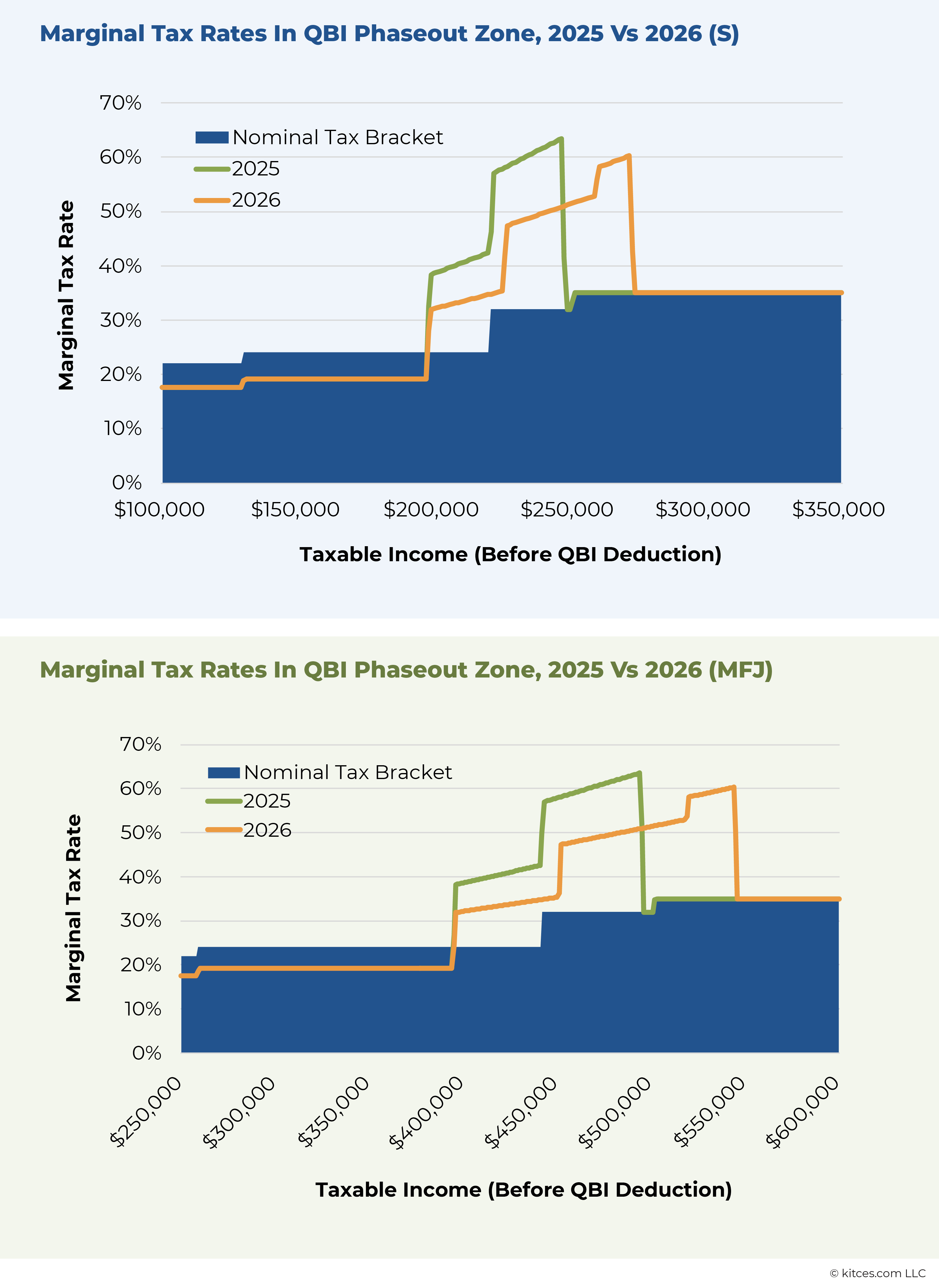

Under OBBBA, some higher-income SSTB owners may get relief from the extreme marginal tax rates in the Section 199A deduction phaseout range. The new law keeps the applicable thresholds of $197,300 (Single) and $394,600 (MFJ) of taxable income (adjusted for inflation each year), above which the deduction begins to phase out for SSTB owners.

However, starting in 2026, OBBBA increases the phaseout range above the threshold to $75,000 for single filers and $150,000 for joint filers – a 50% increase for both ranges. With a wider range of income over which the deduction phases out, the spikes in marginal tax rates are less extreme and increase more gradually than under the previous law.

As shown below, while the marginal rate at the top of the new phaseout range does touch 60% (largely because the new phaseout range now overlaps with the jump to the 35% nominal Federal tax bracket), marginal tax rates will be significantly lower – by 10 percentage points or more – in 2026 for households with taxable income within the current 2025 phaseout threshold range.

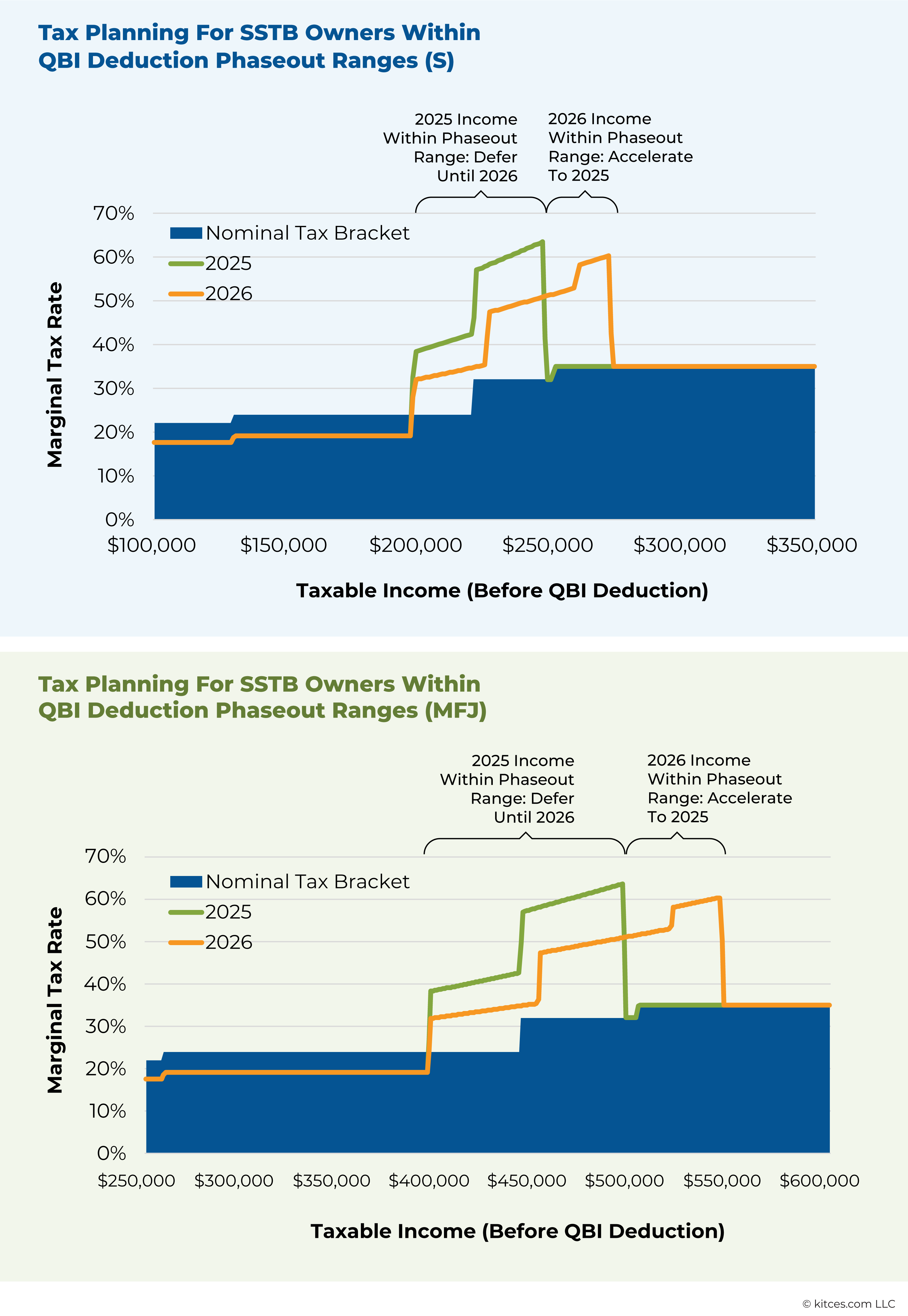

There are two key planning strategies for higher-income SSTB owners, depending on where their taxable income for 2025 and their expected taxable income for 2026 lie relative to the current Section 199A deduction phaseout range.

For those whose 2025 taxable income is expected to be within the 2025 phaseout range, it makes sense to defer as much income as possible – to the extent that it exceeds the applicable threshold – until 2026. This could mean delaying some income-producing projects until after the new year so that income is taxed in 2026 rather than 2025. Even if the owner's income is expected to fall within the phaseout threshold range again in 2026, they will likely pay a much lower marginal tax rate on that income in 2026 than they would in 2025.

SSTB owners might also accelerate deductible expenses into 2025 (e.g., purchasing new business property and electing bonus depreciation to deduct its full cost). Additionally, they could contribute to pre-tax retirement accounts or make deductible charitable contributions – anything to cause their income to be taxed in a year other than 2025. Because, for SSTB owners in the Section 199A deduction phaseout range, marginal tax rates in 2025 are likely to be the highest they'll see in the foreseeable future.

However, for those whose 2025 income is already expected to be above the phaseout range – but who could conceivably fall within the wider 2026 phaseout range – it might be better to take the opposite approach and accelerate income into 2025. Once the Section 199A deduction is fully phased out, the marginal tax rate on any additional income drops back down to the taxpayer's existing marginal rate – in most cases (but not always) their Federal tax bracket. For example, while a married SSTB owner with $490,000 of taxable income in 2025 will pay a 63% marginal tax rate on their next $1,000 of income, one with $495,000 of taxable income would pay ‘only' 32% on their next $1,000 of income.

The expansion of the phaseout range in 2026, however, means that some households with taxable income just above the 2025 range will be within the phaseout range in 2026. Meaning that the same income that would be taxed at 32% or 35% in 2025 could potentially be taxed at the much higher phaseout range rates in 2026. So for SSTB owners who already expect their Section 199A deduction to be fully phased out in 2025 (i.e., their taxable income will be higher than $247,300 for single filers or $494,600 for joint filers), but who expect their 2026 income to be within the top end of the 2026 phaseout range (i.e., less than $275,000 for a single filer and $550,000 for a married filer), it makes sense to accelerate income into 2025 – by wrapping projects up by the end of the year, pushing planned expenditures back to 2026, electing a slower depreciation schedule on business equipment, etc. – to allow that income to be taxed at their lower 2025 marginal tax rate rather than their higher expected 2026 phaseout rate.

It's also worth noting that some taxpayers in this income range may also be contending with the phaseout of the State And Local Taxes (SALT) deduction, which phases down from $40,000 to $10,000 between $500,000 to $600,000 of AGI. This can cause marginal tax rates to spike up to 45.5% in the SALT deduction phaseout range. However, an SSTB owner whose income falls within the 2026 Section 199A deduction phaseout range could potentially pay an even higher marginal tax rate on that same income next year. In other words, even if accelerating income to 2025 adds enough to the household's AGI to phase down their SALT deduction, doing so may still be beneficial to avoid an even higher rate next year. Either way, it's crucial to run the numbers through software or with a tax professional to understand what the cumulative impact will be from recognizing income in 2025 versus 2026.To sum up, for SSTB owners who expect their 2025 income to be within the 2025 Section. 199A deduction phaseout range of $197,300 (S) / $394,600 of taxable income (before accounting for the deduction), it's likely best to defer income to 2026 or later to the extent it's possible. And for SSTB owners whose 2025 income already falls above the 2025 upper phaseout threshold, but whose 2026 income is expected to be within the 2026 phaseout ranges of (approximately) $200,000-$275,000 (S) / $400,000-$550,000 (MFJ), it could make sense to accelerate income to 2025.

Complete Home Energy Projects Before December 31

Finally, OBBBA accelerated the sunset date of several tax credits created by the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 aimed at incentivizing home energy efficiency improvements and expanding the use of clean energy for homes and cars. One of these deadlines has already passed: The Clean Vehicle Credits for new and used electric or fuel cell vehicles, which expired on September 30 2025.

For some of the home energy-related credits, however, taxpayers still have until December 31, 2025, to meet the eligibility requirements – which gives them some time (albeit not much) to qualify for the credits.

The credit that most households would realistically qualify for is the Energy Efficient Home Improvement Credit (EEHIC) under IRC Section 25C. This credit covers a wide range of home projects that can improve energy efficiency, including windows, doors, insulation and sealing materials, and home energy audits to identify the most cost-effective improvements for energy and cost savings.

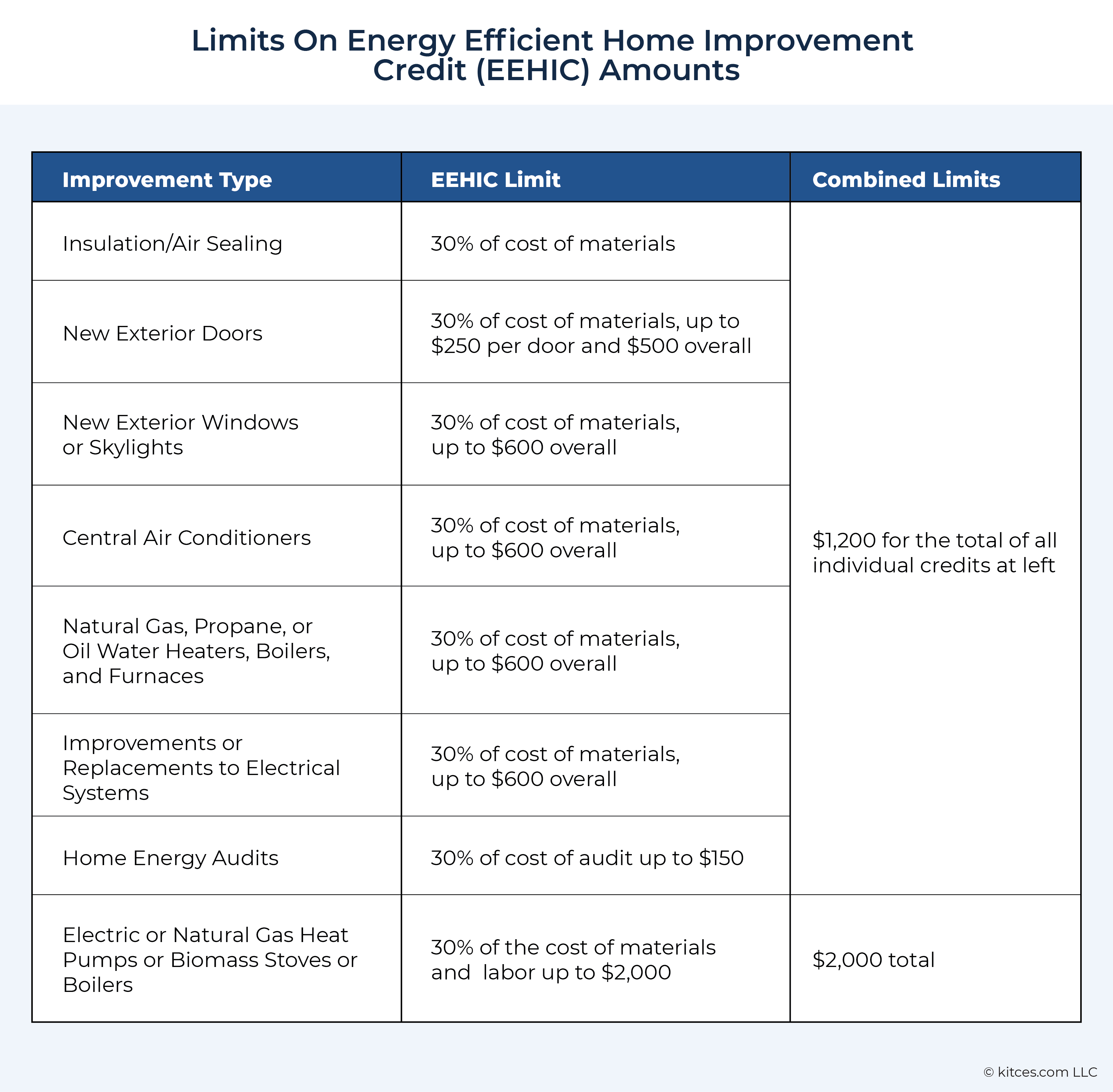

At a high level, the EEHIC equals 30% of the amount of qualified expenses paid during the year, subject to certain underlying limits on specific property types:

As shown above, the combined EEHIC limit for all the eligible costs except heat pumps, biomass stoves, or biomass boilers is $1,200, while heat pumps and biomass stoves or boilers are subject to their own individual limit of $2,000. The maximum EEHIC that can be taken in 2025, then, is $3,200. The improvements must be made to the taxpayer's primary residence – the credit isn't available for improvements made to additional homes or rental properties.

Another incentive is the Residential Clean Energy Credit (RCEC), which equals 30% of the cost of qualified expenses. This credit applies to materials and labor costs for installing solar panels, solar water heaters, wind turbines, geothermal heat pumps, fuel cells, and home battery storage systems.

To qualify for the credit, all projects must be installed or placed in service by December 31, 2025. At this point, the tight timeline may be unrealistic for many of the bigger-scale projects – e.g., it could be difficult to get a heat pump or solar panels installed in the amount of time left to claim the credit. However, smaller improvements, like doors or windows, might still be feasible. And, at the least, scheduling a home energy audit – which can often include free improvements like replacing old incandescent light bulbs with LEDs, installing weatherstripping on doors, and swapping out old power strips – can qualify for a $150 credit (though some cities and states provide home energy audits for free to their residents).

Even if there's not enough time to qualify for the Federal clean-energy tax credits, many states and cities offer their own credits, rebates, and financing subsidy programs to incentivize such projects. So homeowners may still find meaningful savings for energy efficiency improvements to their homes.

The end of the tax year is often a good time for financial advisors to show their value, as clients' income and deduction pictures come into clearer view and tax planning opportunities rise to the surface. Advisors who can spot those opportunities, year-end deadline can provide concrete value that, in many cases, shows up literally right on the client's tax return.

OBBBA, with its plethora of new provisions taking effect in either 2025 or 2026, provides some unique one-time planning opportunities for clients ranging from charitable givers to 529 plan owners to employees with Incentive Stock Option (ISO) compensation to pass-through business owners. And so, while tax planning might be an annual process, advisors can use these strategies to find even more ways to add value above and beyond the "usual" year-end planning.

Leave a Reply