Executive Summary

Since the Tax Cuts & Jobs Act (TJCA) was passed in 2017, few households have been subject to the Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT), which TCJA restructured so that it applied mainly to a select number of upper-income households. But with the anticipated sunset of TCJA in 2026 and the reversion to the pre-2018 AMT rules, a large subset of households will find themselves owing AMT – many of whom will do so for the first time.

At a high level, the AMT calculation works by adding a number of 'adjustment items' to a taxpayer's taxable income, most commonly including the standard deductions, the deduction for state and local taxes, interest from tax-exempt 'private activity' bonds, and unrealized gains on the exercise of Incentive Stock Options (ISOs). Once these adjustment items have been added to the taxpayer's regular income sources to calculate their 'AMT income', a single large AMT exemption is subtracted from that amount to arrive at the tax base off of which AMT is calculated. The tax itself is calculated using 2 brackets of 26% and 28%, and the taxpayer owes AMT if their tax as calculated using the AMT method is higher than it is when using the 'regular' tax calculation.

The sunset of TCJA will add back several common adjustment items that will create potential AMT exposure for many households. For example, personal exemptions and miscellaneous itemized deductions such as investment advisory fees, both of which will be reinstated after TCJA's sunset. Additionally, the elimination of the $10,000 limit on state and local tax deductions will make that adjustment much higher for property owners and households in high-tax states.

Furthermore, TCJA's sunset is set to reduce the amount of the AMT exemption, as well as to drastically lower the income threshold at which the exemption begins to phase out. Which means AMT will be triggered more frequently in households with 'only' $100,000–$600,000 of income. Households subject to AMT may also face a 'bump zone' in the phaseout range of the AMT exemption where any additional income is effectively taxed at a marginal rate of 32.5% and 35%.

For financial advisors, understanding the upcoming rule changes around AMT can help with identifying which clients might be subject to AMT starting in 2026. Which, from a practical perspective, can help with understanding whether the client needs to boost tax withholding or estimated payments in anticipation of the AMT tax owed – but can also help with recognizing planning opportunities to either avoid AMT exposure or reduce its impact. For example, clients with unexercised ISOs could exercise those options prior to TCJA's sunset without AMT exposure. However, if they were to wait until 2026, they would owe AMT (and need to find or borrow funds to pay the AMT triggered by the exercise). Although for clients currently in the AMT 'bump zone', it may actually be better to delay recognizing the income instead!

The key point is that, while it won't always be possible to avoid AMT (since AMT itself is intended to prevent higher-income households from avoiding taxes via high deductions and tax-exempt income sources), planning for AMT's changes post-TCJA sunset can help to minimize the impact of AMT and at least avoid any 'surprise' tax bills for those who don't see it coming. And because TCJA's sunset is expected to overwhelmingly increase households' exposure to AMT, there's not much downside in being proactive to avoid or minimize future AMT – since the downside if TCJA is ultimately extended is that there would be little or no AMT exposure anyway!

Since the passage of the Tax Cuts & Jobs Act (TCJA) in 2017, very few households have needed to contend with the Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT). Before 2017, AMT exposure was relatively commonplace among households with 6-figure incomes; but TCJA – though it didn't completely eliminate AMT – made enough changes to the preexisting AMT calculation so that it now affected only a small segment of very high-income households: According to some estimates, the number of taxpayers subject to AMT decreased by more than 96% after TCJA took effect, from over 5 million in 2017 (the last year under the pre-TCJA rules) to around 200,000 in 2018.

However, with the planned sunset of most TCJA provisions at the end of 2025, AMT is likely to become relevant again for a much broader group of taxpayers than it has been since 2018. Some households may encounter AMT for the first time, while others might be reacquainting themselves after an 8-year break. Either way, with the 1-year mark until TCJA's scheduled sunset approaching, now is a good time to review how the AMT system works, who might be subject to it if the provisions expire as planned in 2026, and what actions taxpayers can take if they expect to be affected by AMT in the near future.

How AMT Functions

At a high level, AMT is a separate method of calculating income tax that runs parallel to the 'regular' tax system, which functions by eliminating many common deductions and other tax benefits and calculating the tax on the resulting income using a simplified rate structure. And although it's called the “Alternative” Minimum Tax, it would be more accurate to describe AMT as a mandatory minimum tax, since taxpayers must use the method – regular or AMT – that results in the higher tax.

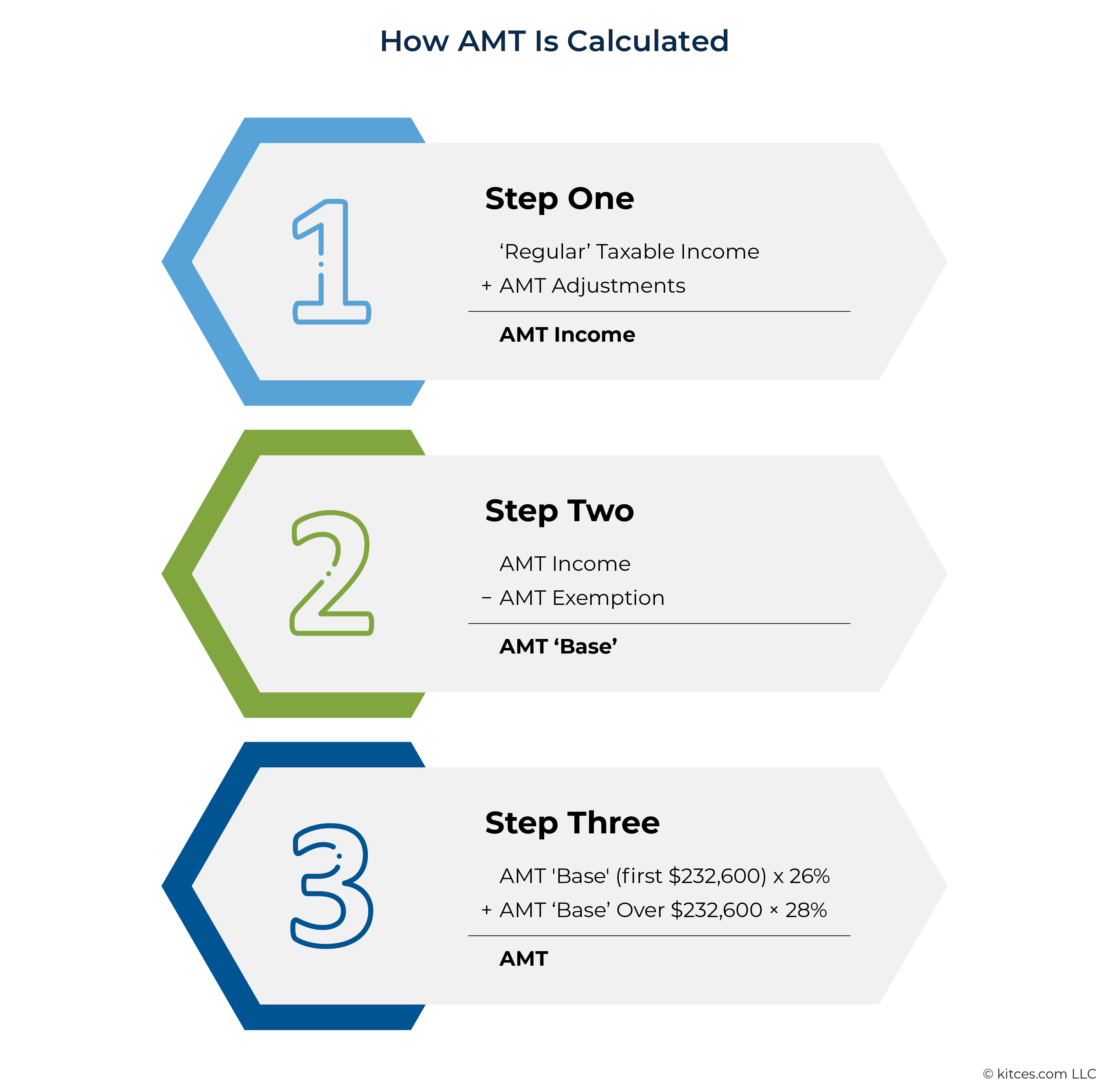

The calculation for AMT has 3 basic steps:

- Adjustments to 'regular' taxable income are made by adding back specific deductions that are reduced or eliminated by the AMT. These include some very common ones, such as the standard deduction and the itemized deduction for State And Local Taxes (SALT). Additionally, several types of income that are normally tax-free or tax-deferred – like the interest on 'private activity' state and local bonds and the difference between the exercise price of Incentive Stock Options (ISOs) and the share price upon exercise – are included in a person's AMT income.

- After adding back the required income and deductions, a single large AMT exemption is subtracted from AMT income (although the exemption is phased out at higher income levels) to come to the AMT income 'base' on which the tax is calculated. In 2024, the AMT exemption is $85,700 for single taxpayers and $133,300 for MFJ. The exemption begins phasing out at $609,350 (single) or $1,218,700 (MFJ) of AMT income.

- The resulting income is taxed using a simple 2-bracket structure of 26% on the first $232,600 (which is the same for both single and married filers) and 28% on any additional income.

After calculating tax using both the 'regular' and AMT methods, the taxpayer owes whichever method results in the highest tax.

Technically, the AMT reported on the tax return is the difference between the regular tax and the AMT tax, but the amount of tax owed in the end is the same as what's calculated using the steps above.

The net effect of AMT is to impose, as the name implies, a minimum level of tax on higher-earning taxpayers who claim significant deductions or certain kinds of tax-exempt income to reduce their taxable income. What has changed as the tax code has evolved is how high a household's (pre-deduction) income must be and how much in the way of deductions or tax-exempt income (i.e., AMT “adjustment items”) they must have in order for the AMT to exceed their regular tax. Ultimately, these 2 factors – overall income and the amount and types of adjustment items – drive a household's exposure to AMT.

Calculating AMT Under TCJA

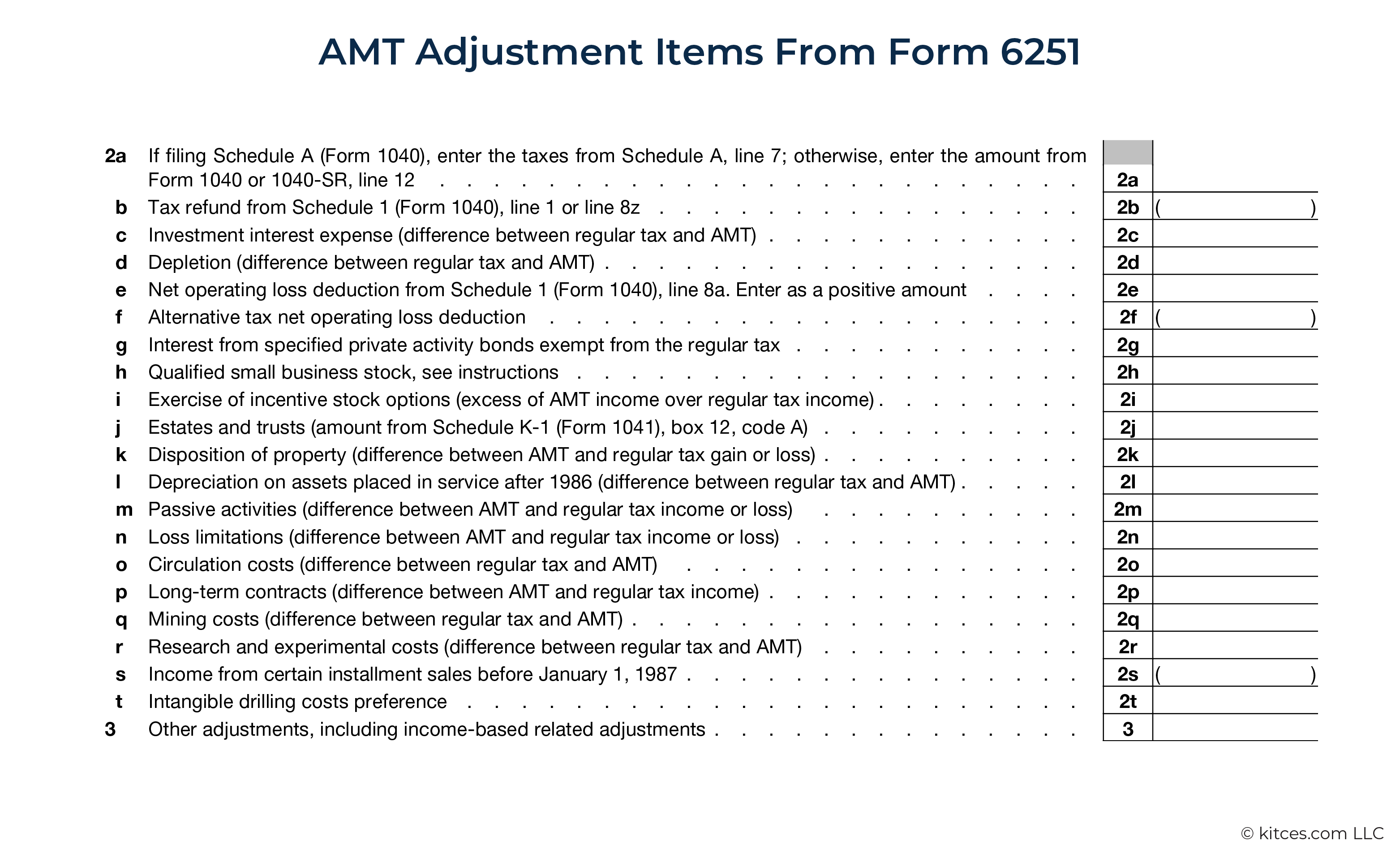

Many factors can affect a taxpayer's AMT exposure. As shown in the excerpt below from the 2023 Form 6251 (used for calculating AMT on the tax return), there are 20 different AMT adjustment items, which either increase or decrease a household's taxable income for AMT purposes.

In practice, however, under TCJA, AMT exposure most commonly comes from just 4 types of adjustment items:

- The standard deduction;

- The deduction for State And Local Taxes (SALT) paid;

- Interest from 'private activity' bonds, which are commonly held in municipal bond funds and are generally Federally tax-exempt, but are included in income for AMT purposes; and

- For employees receiving Incentive Stock Option (ISO) compensation, the difference between the option's exercise price and the stock's price on the exercise date (which is generally deferred as income until the stock is sold, but is added to income for AMT purposes in the year the option is exercised).

Although most of the above items increase a household's income for AMT purposes, the AMT exemption decreases the amount of income subject to AMT. Given that the AMT exemption is so large ($85,700 for single and $133,300 for married filers in 2024), and the fact that it doesn't start to phase out until incomes reach $609,350 for single and $1,218,700 for married filers, most taxpayers aren't subject to AMT unless they have a substantial amount of AMT adjustments.

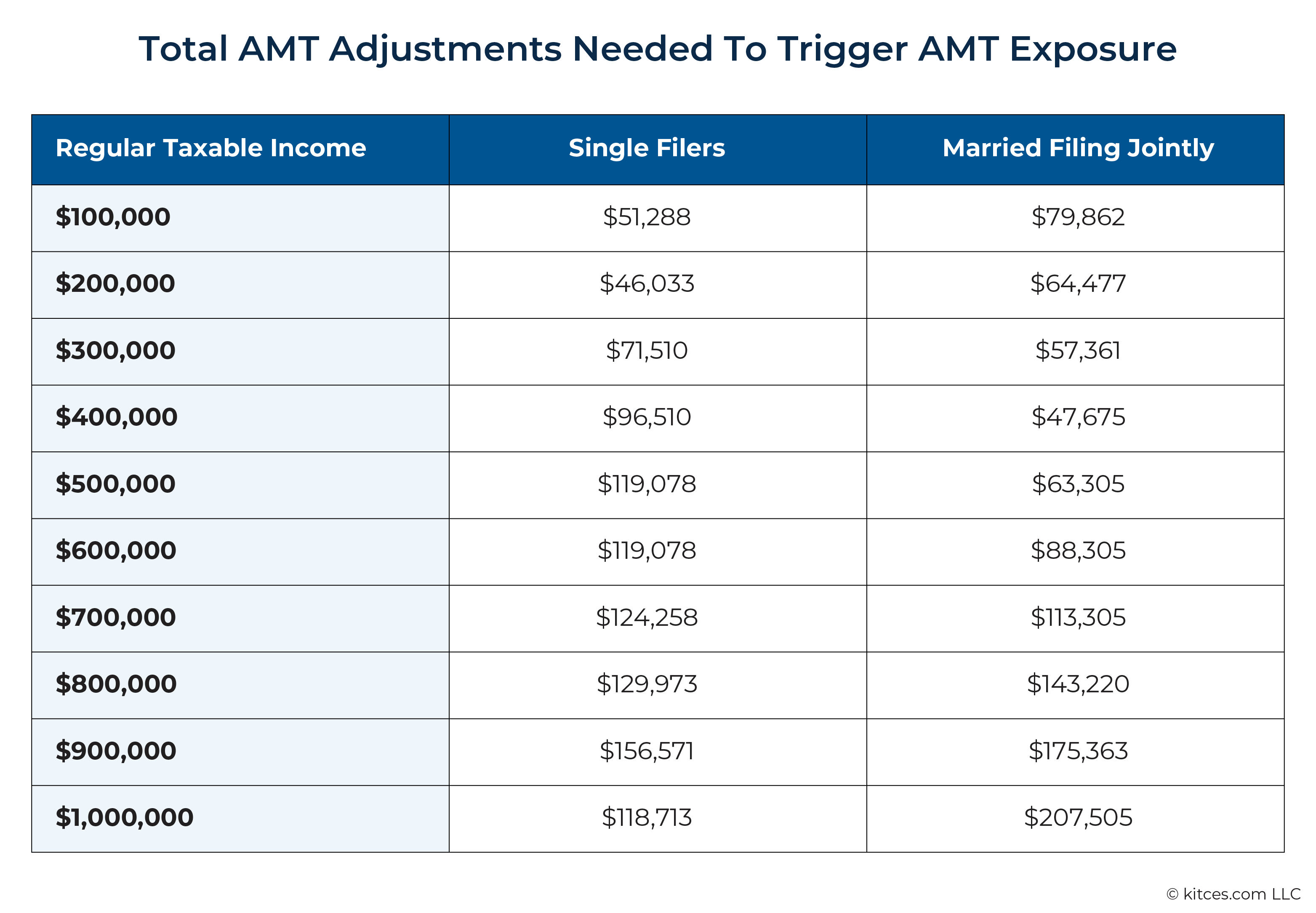

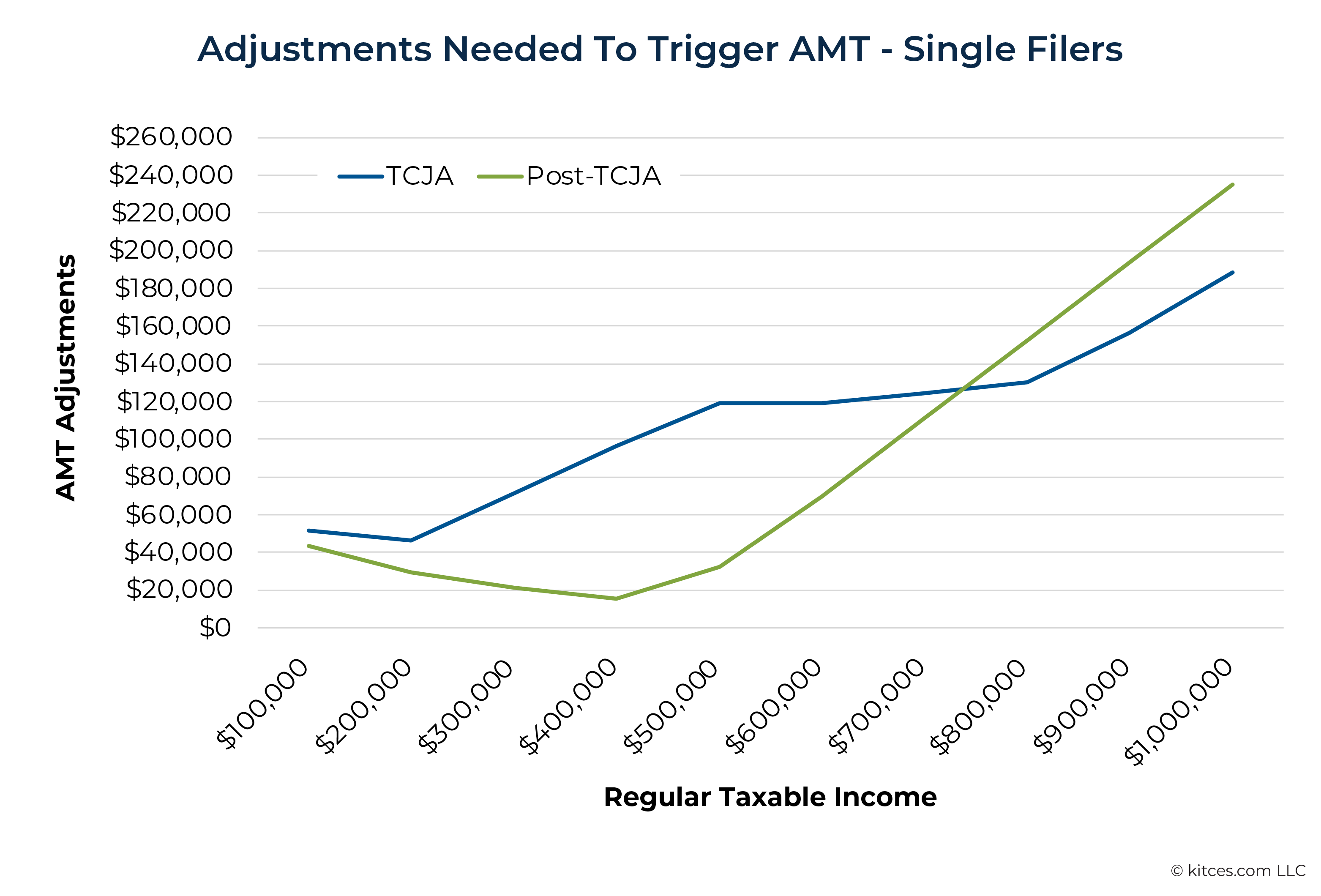

As shown below, the amount of AMT adjustments needed to trigger AMT – that is, the net total of all the AMT adjustment items above that are added to income for AMT purposes – varies based on income level, but is never less than $40,000 (and for many income levels is substantially more than that):

Notably, because the standard deduction – which counts as an AMT adjustment item – is currently 'only' $14,600 for single filers and $29,200 for married couples filing jointly, no one taking the standard deduction is subject to AMT unless they have additional adjustment items that, when added with the standard deduction, push them into AMT. Additionally, with the TCJA limiting the deduction for state and local taxes to $10,000, that alone is also insufficient to trigger AMT exposure under the current law.

In other words, whether a taxpayer takes the standard deduction or itemizes deductions under the regular tax system, the only way to trigger AMT exposure under the current TCJA law is through a combination of multiple adjustment items.

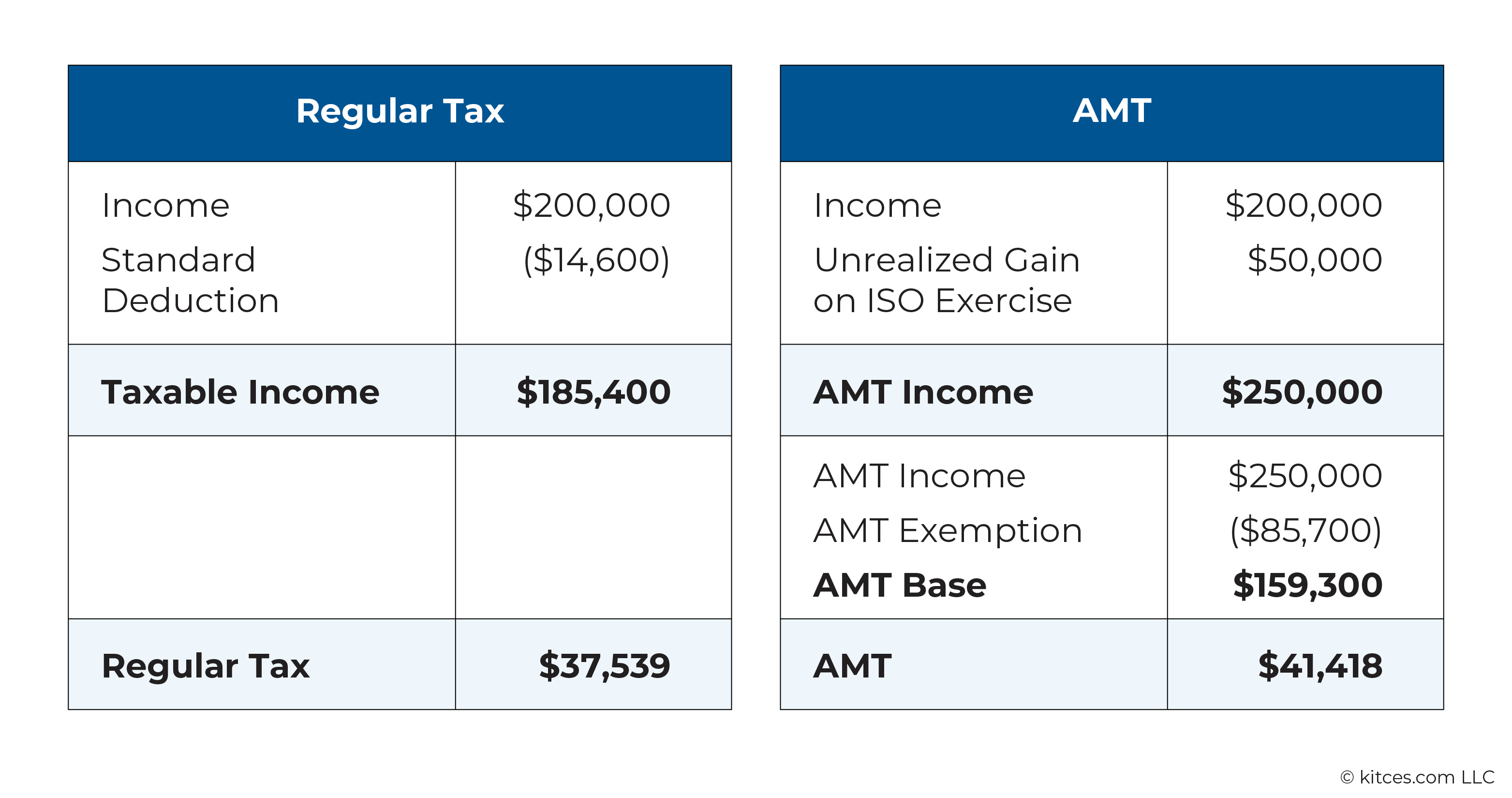

Example 1: Royal, a single filer taking the standard deduction, earned $200,000 working for a startup in 2024. Additionally, Royal exercised 100 of his employer's Incentive Stock Options (ISOs) at $50 each when the stock was valued at $100 per share, resulting in 100 × ($100 − $50) = $50,000 in unrealized gains. Although these gains are deferred for regular tax purposes, they are added to income for AMT.

Both the standard deduction and the ISO income are added to Royal's income for AMT purposes, resulting in $14,600 + $50,000 = $64,600 in total adjustments.

The calculations for Royal's regular tax and AMT are as follows:

Because the AMT is the higher of the 2 calculations, Royal will be subject to AMT rather than regular tax as a result of the exercise of his ISOs.

AMT Exemption Phaseouts At Upper Incomes

The large AMT exemption, subtracted from AMT income to calculate the 'base' to which the 26%/28% AMT rates are applied, ensures that households with lower income levels won't be subject to AMT. However, as both the taxpayer's overall amount of income and the amount of their AMT adjustments increase, the AMT becomes larger compared to the regular tax calculation, making it more likely that the taxpayer will be subject to AMT. And at a certain level of income, the AMT exemption begins to phase out at a rate of 25% of the amount over the phaseout threshold.

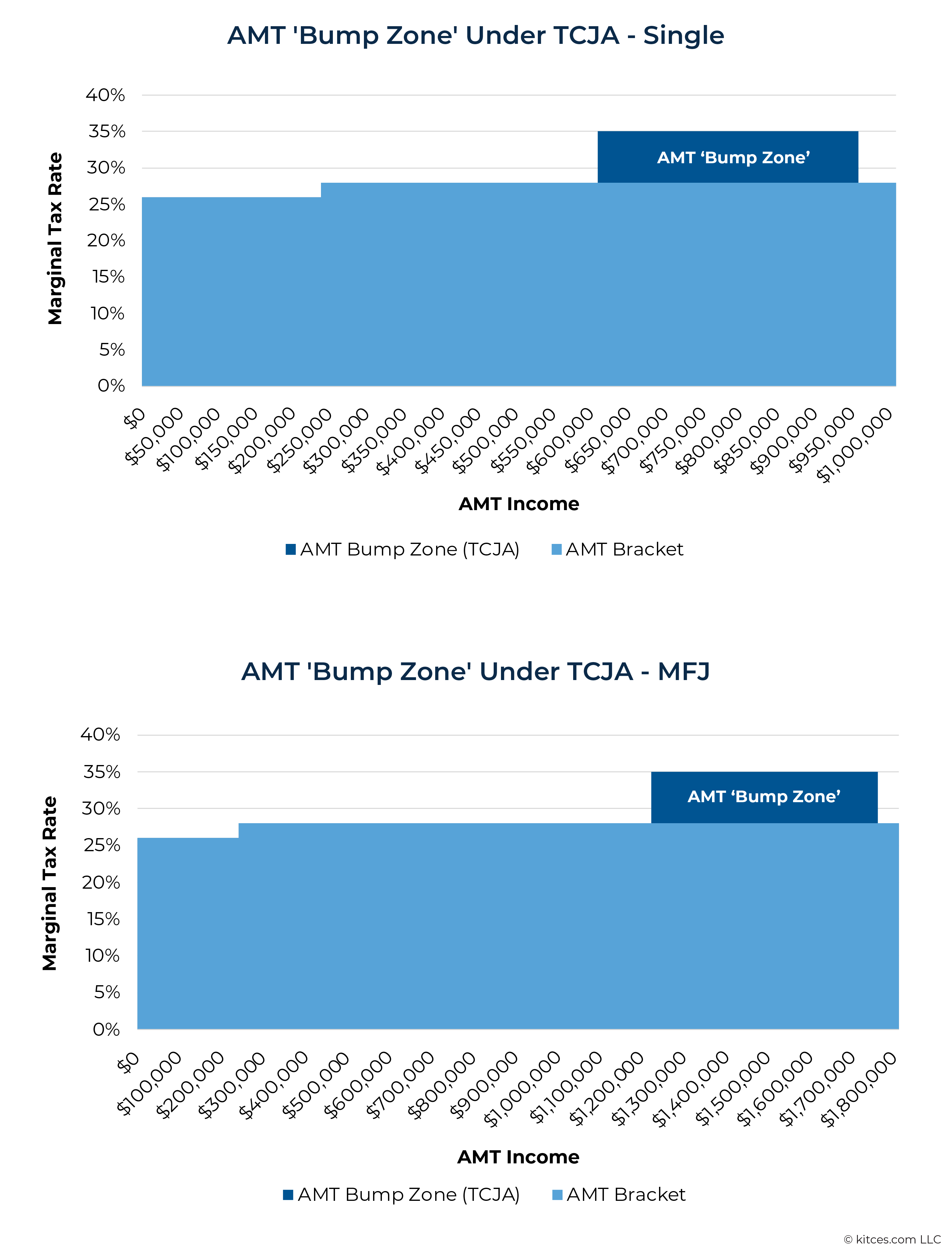

The effect of the AMT exemption phaseout, as shown below, is to essentially create a third AMT 'bracket' of 35% - i.e., a 'bump zone' – within the income phaseout range, before falling back to 28% once the AMT exemption is fully phased out.

The caveat, however, is that under the current TCJA law, the exemption phaseout thresholds are set at very high income levels: $609,350 of AMT income for single filers, and $1,218,700 for married taxpayers filing jointly. Which means that anyone within the phaseout range would also likely be in the highest (35% and 37%) regular tax brackets, making it harder for the household's AMT to be higher than their regular income and therefore making them unlikely to be subject to AMT, unless they had a very high amount of AMT adjustments.

For instance, at the phaseout threshold of $609,350 for single filers, a taxpayer would need at least $119,078 in AMT adjustments to be subject to AMT. This would result in a regular taxable income of $609,350 − $119,078 = $490,272, placing them in the 35% regular tax bracket. Similarly, for a married filer at the MFJ phaseout threshold of $1,218,700, the household would need at least $210,229 in adjustments, resulting in a regular taxable income of $1,008,471 and placing them in the 37% regular tax bracket.

AMT Credit Allows Taxpayers To Recoup AMT Paid In Prior Years

As mentioned earlier, the AMT as reported on the tax return is technically the difference between the individual's regular tax and the tax calculated by the AMT method. This is important because AMT owed on certain types of income in 1 year can be paid back to the taxpayer in future years in the form of an “AMT Credit” for up to the full amount of the original AMT paid on that income – but only to the extent that the taxpayer doesn't owe AMT in future years.

When a person owes AMT in 1 year, it generates a credit carryforward that is applied to the next year's tax return as an available AMT credit. Notably, only AMT from certain types of income sources can generate a future AMT credit. If there were AMT adjustments for the standard deduction, state and local taxes, and tax-exempt interest, then the AMT attributable to those adjustments would be subtracted from the amount that could be used as a future credit. However, for other types of adjustments – such as unrealized capital gains from an ISO exercise – any AMT owed does generate a carryforward for a future tax credit.

The AMT credit carryforward can then be used to offset taxes owed in future years. However, the AMT credit for any given year can only be claimed if the regular tax for that year exceeds the tax calculated by the AMT method. Any unused AMT credit is then carried forward again to future years and never expires, meaning that it can continue to be carried forward until fully used.

Example 2: Richie owed AMT last year after exercising his employer's ISOs, which generated an AMT credit carryforward of $40,000.

This year, Richie doesn't owe any AMT, and his tax calculated by the regular method is $10,000 higher than his tax calculated by the AMT method. He can therefore take a $10,000 AMT credit this year. The remaining $30,000 of available AMT credit is then carried forward to next year, and so on, until the entire AMT credit is fully used.

For households that regularly owe AMT, then, it can be hard to benefit from accumulated AMT credits, which can only be used when the taxpayer doesn't owe AMT. However, because the credits never expire, changes in income – whether due to retirement, a change in compensation structure (e.g., cash compensation rather than ISOs), or even an overall increase in income that results in owing regular tax over AMT – can eventually break the logjam and allow the accumulated AMT credits to finally be used.

AMT Changes After The TCJA Sunset

After 2025, the Tax Cuts & Jobs Act is scheduled to expire, bringing major changes to the AMT. In 2026, the AMT system will revert to the pre-2018 rules, which may feel like new rules for those encountering them for the first time (and for those who had grown accustomed to the current TCJA rules).

What isn't changing about AMT is the basic AMT calculation: Regular taxable income, plus any AMT adjustments, minus the AMT exemption (which is phased out at higher income levels), equals the base on which the tax is calculated. The 2-bracket structure and the 26% and 28% rates will also remain the same. And the calculation for the AMT credit will remain basically unchanged.

The major changes instead involve the underlying numbers that drive the AMT calculation: the amounts and types of AMT adjustment items, the amount of the AMT exemption, and the income thresholds at which the AMT exemption phases out.

Changes To Deductions And Exemptions Will Complicate AMT Planning Post-TCJA

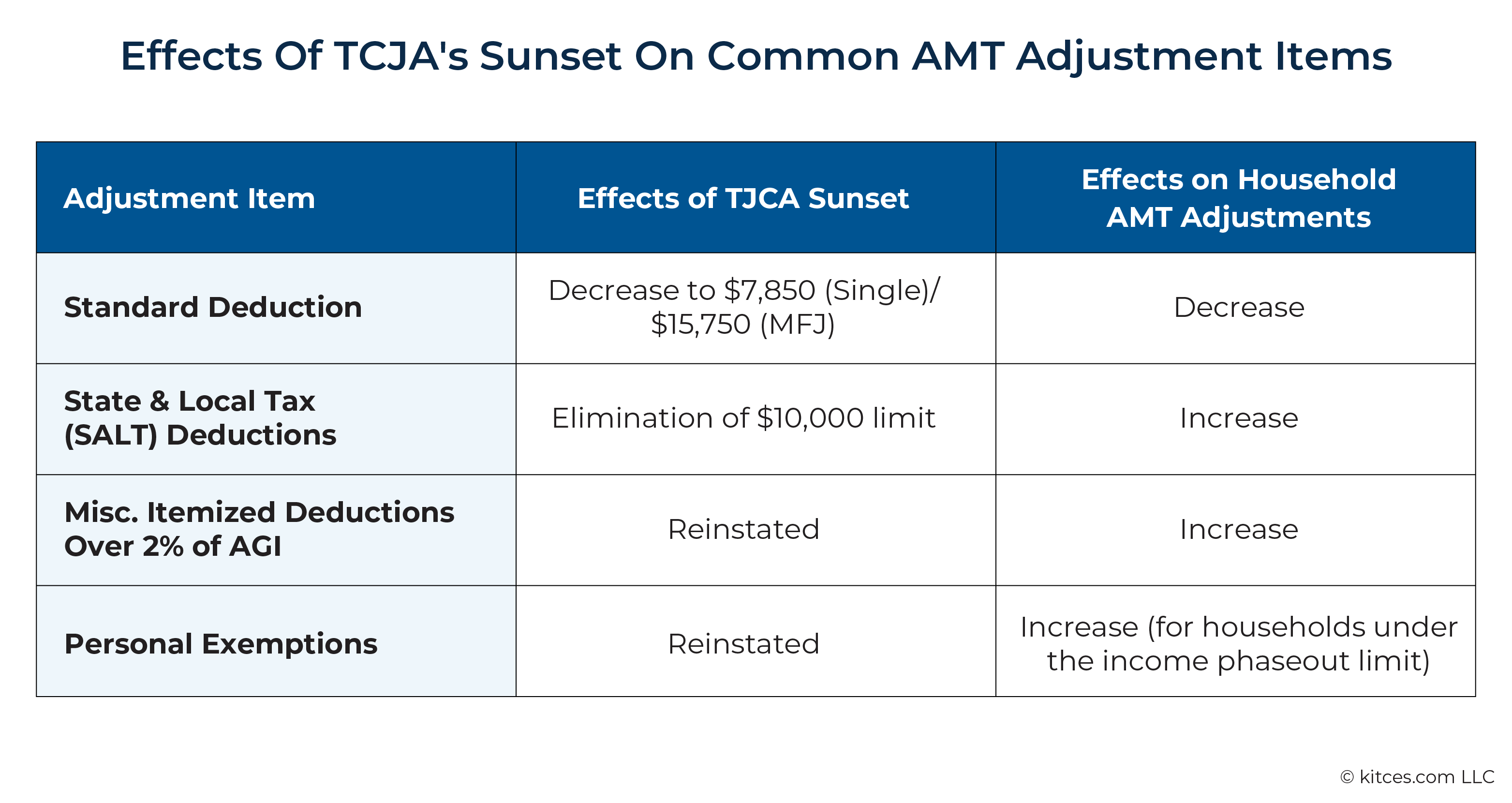

To start, the AMT adjustments that are added to regular taxable income for AMT purposes will change in complex ways with TCJA's expiration. Some adjustments will increase, some will decrease, and some will effectively cancel each other out.

For example, after the TCJA sunset, the standard deduction will decrease by almost 50%, from the current $14,600 for single filers and $29,200 for MFJ to approximately $7,850 for single filers and $15,750 for MFJ. At the same time, the $10,000 limit on itemized deductions for state and local taxes is set to expire, and miscellaneous itemized deductions (like investment management fees and unreimbursed employee expenses) exceeding 2% of gross income – which were eliminated by TCJA – will be reinstated.

As a result, many more taxpayers, with a lower standard deduction and more potential itemized deductions, will likely begin itemizing after TCJA's expiration. However, both state and local taxes and miscellaneous itemized deductions will be added back to income for AMT purposes, meaning there will be more AMT adjustments post-TCJA for taxpayers who, for example, pay higher state taxes or use advisors to manage their investments.

On the other hand, TCJA's expiration will also reinstate the so-called Pease limitation, which phases out itemized deductions at higher income levels (starting at approximately $324,300 in Adjusted Gross Income for single filers and $389,150 for joint filers). So those with incomes above the Pease threshold may actually have less exposure to AMT than those with lower incomes, since the phaseout reduces the amount of itemized deductions to add back to income for AMT purposes.

Additionally, TCJA's sunset will also reinstate personal exemptions, which allow taxpayers to subtract a specified amount from their taxable income for each taxpayer and dependent listed on the tax return ($4,050 in 2017, when exemptions were last allowed; estimated to be around $5,050 in 2024 dollars). These, too, are considered adjustment items for AMT purposes, meaning that a household with multiple dependents, and thus more personal exemptions, will have more AMT adjustments after TCJA expires. Except, like itemized deductions, personal exemptions will also phase out at higher incomes, using the same AGI thresholds of an estimated $324,300 for single taxpayers and $389,150 for MFJ, which will reduce their impact on AMT exposure for those above the threshold.

At first glance, the overall effect of the post-TCJA changes to the most common AMT adjustment items, as shown below, may seem like it would increase the potential AMT exposure for many households – particularly for those who have high state and property taxes, multiple dependents, and investment management fees from taxable accounts. However, the impact will be much smaller for households above the Pease limitation and personal exemption phaseout thresholds, where many of those deductions are already reduced or eliminated.

AMT Exemption And Phaseout Levels Decrease After TCJA's Sunset

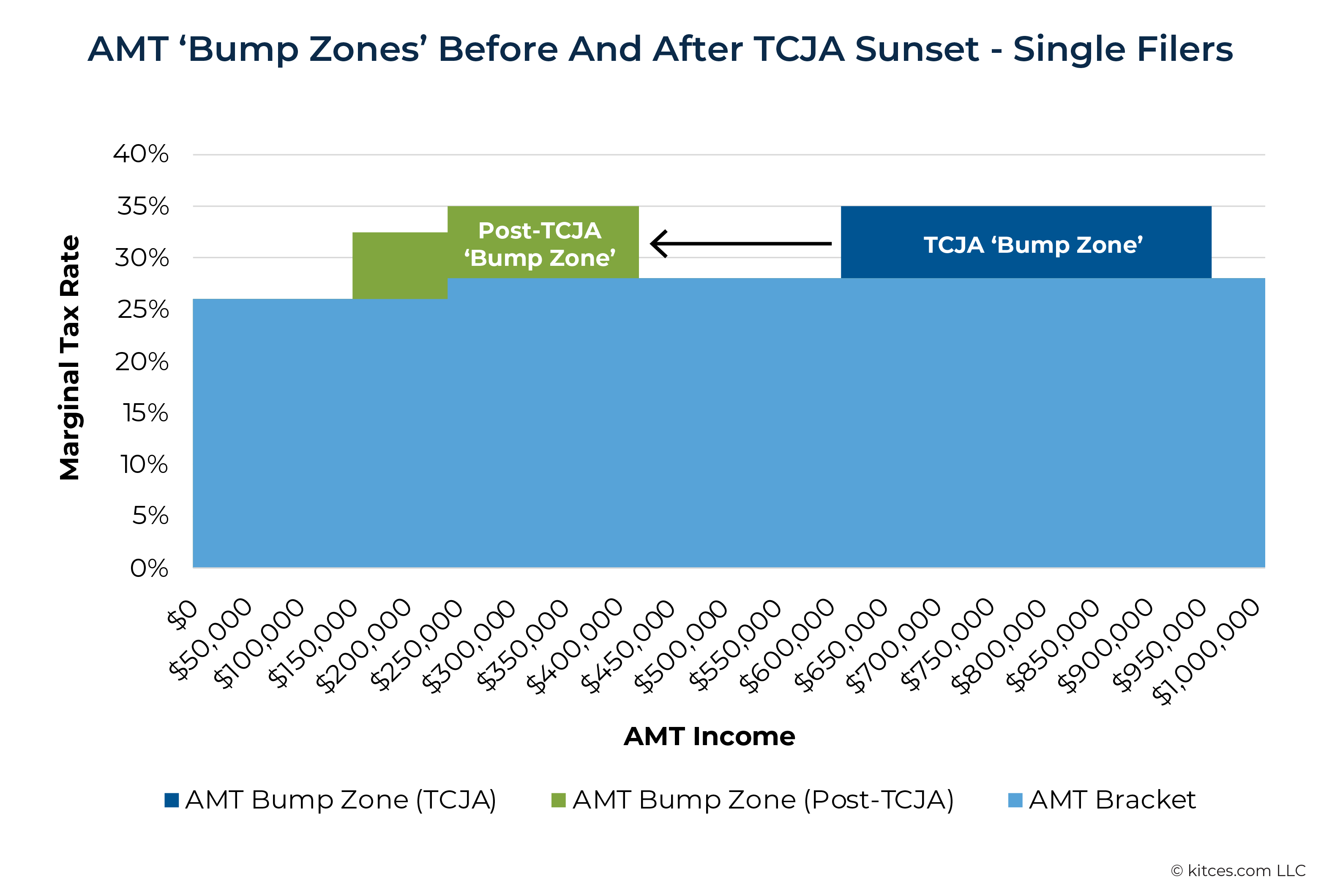

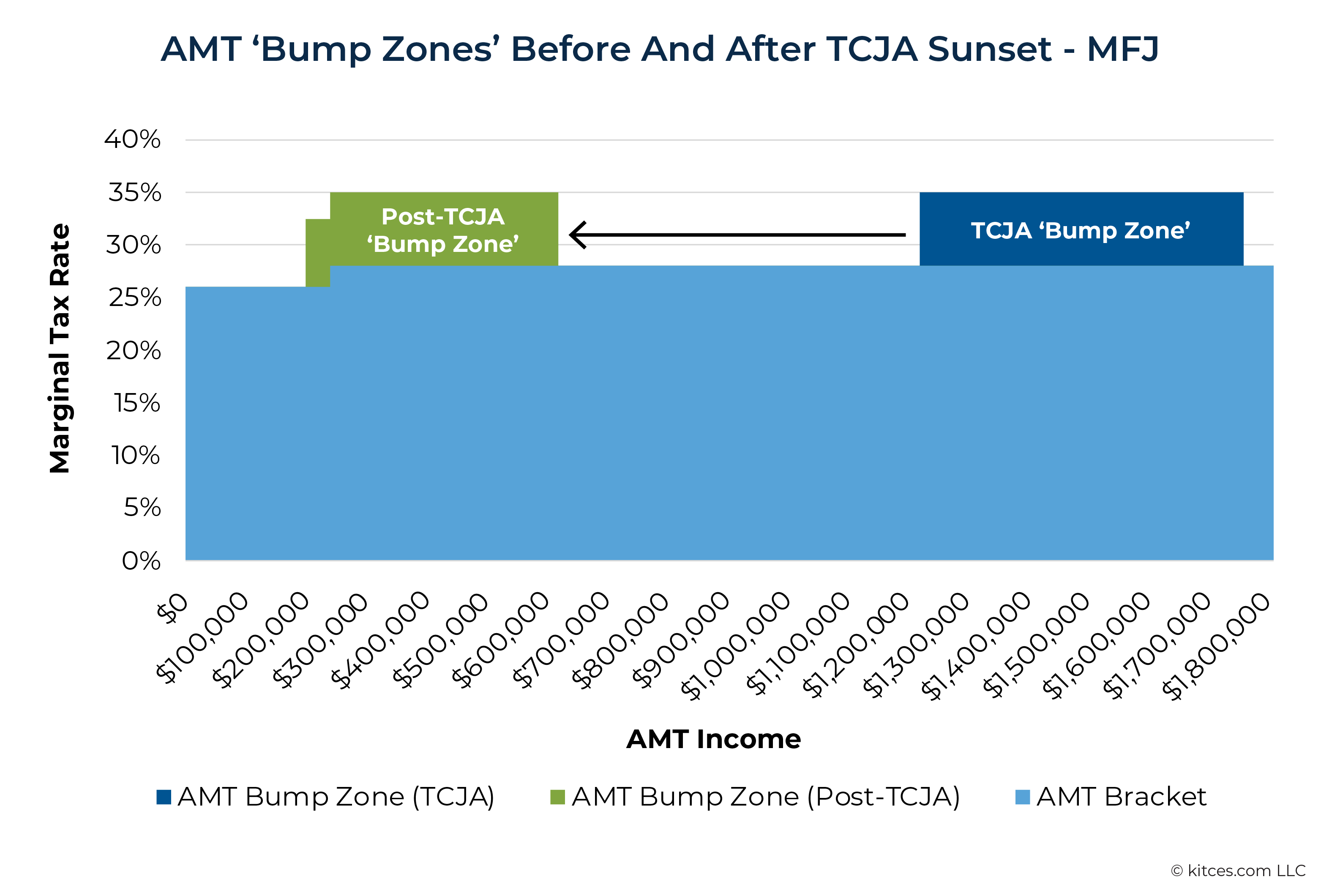

TCJA's expiration will lower the AMT exemption from $85,700 to (an estimated) $67,300 for single filers and from $133,300 to $104,800 for joint filers. Additionally, the income level where the AMT exemption begins to phase out will be markedly lower post-TCJA, decreasing from $609,350 to approximately $149,700 for single filers and from $1,218,700 all the way down to $199,500 for joint filers.

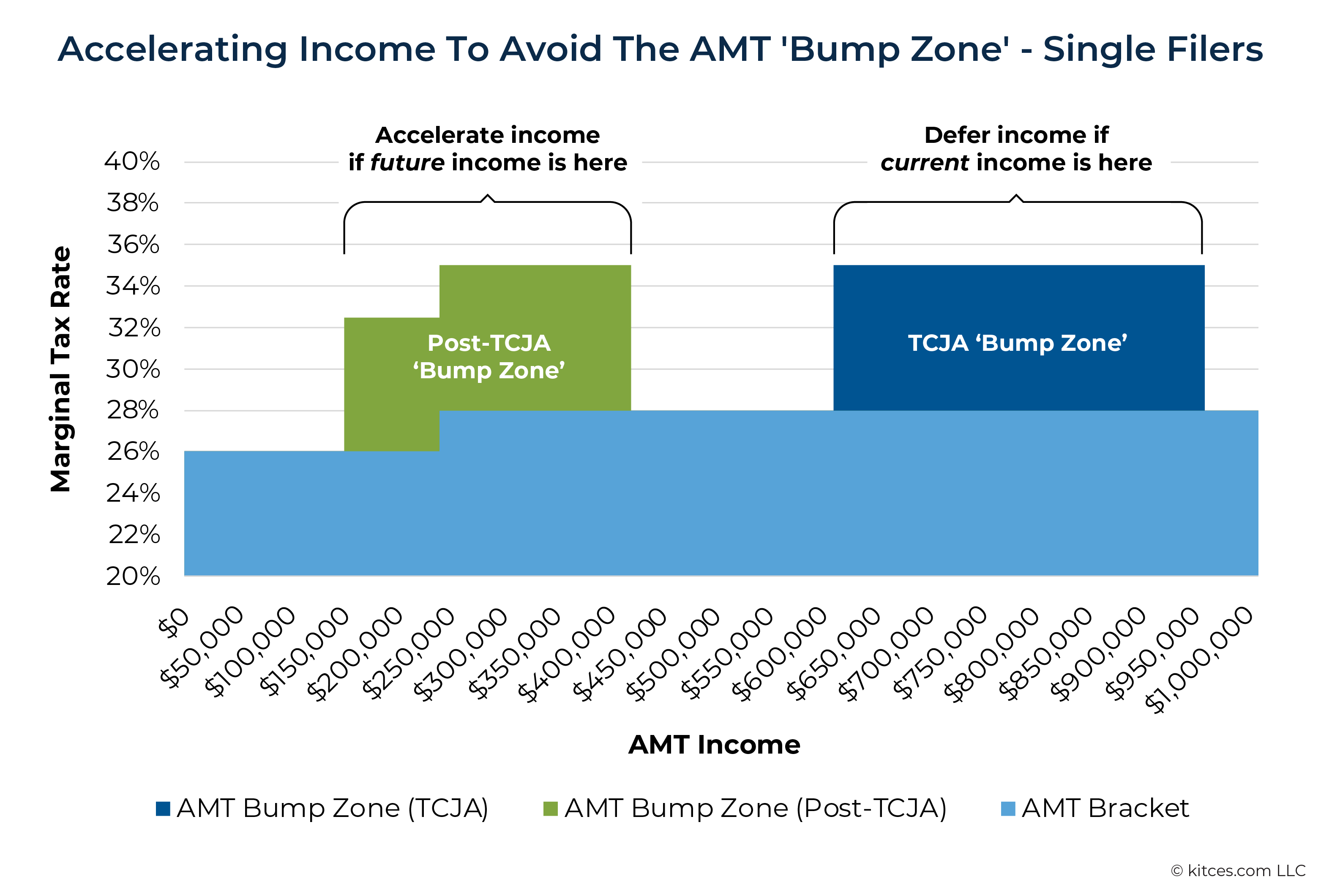

The effect of these changes, as shown in the 2 graphics below, is that the 'bump zone' – where taxpayers subject to AMT pay an effective 32%/25% marginal rate on any additional income – shifts significantly downward on the income spectrum. For single filers, the bump zone will move from $609,350–$952,150 of AMT income under TCJA to $149,700–$418,900 of AMT income post-TCJA.

For joint filers, the difference between pre- and post-TCJA sunset AMT bump zones is even more drastic. Currently, under TCJA, the bump zone doesn't even begin until the household reaches $1,218,700 in AMT income and stretches out to $1,751,900. However, after TCJA expires, the bump zone will start at approximately $199,500 and go up to $618,700, affecting a much greater number of households than the current system.

The other upshot of the changes to the AMT exemption after TCJA's sunset is that, for most households, it will take much less in AMT adjustments to trigger AMT exposure after the sunset than it does under current TCJA rules. As the chart below shows, for single filers under TCJA (represented by the blue line in the chart below), the amount of adjustments needed to make AMT higher than regular tax bottoms out at around $40,000 for those with $200,000 in regular taxable income, then grows to almost $120,000 by the time taxable income reaches $500,000, and continues to increase from there.

After TCJA's expiration (represented by the green line), the bar for AMT exposure stays lower for longer. Single filers with between $200,000 and $500,000 of regular taxable income will need far less in AMT adjustments, making them more likely to owe AMT with 'only' $20,000–$40,000 in adjustments. However, for those with over $700,000 in regular taxable income, more adjustments will be required to trigger AMT exposure after the TCJA sunset. This is due to the increase in the highest regular tax bracket from 37% to 39.6%, which will make it harder in general for AMT to exceed regular tax for those in the top bracket.

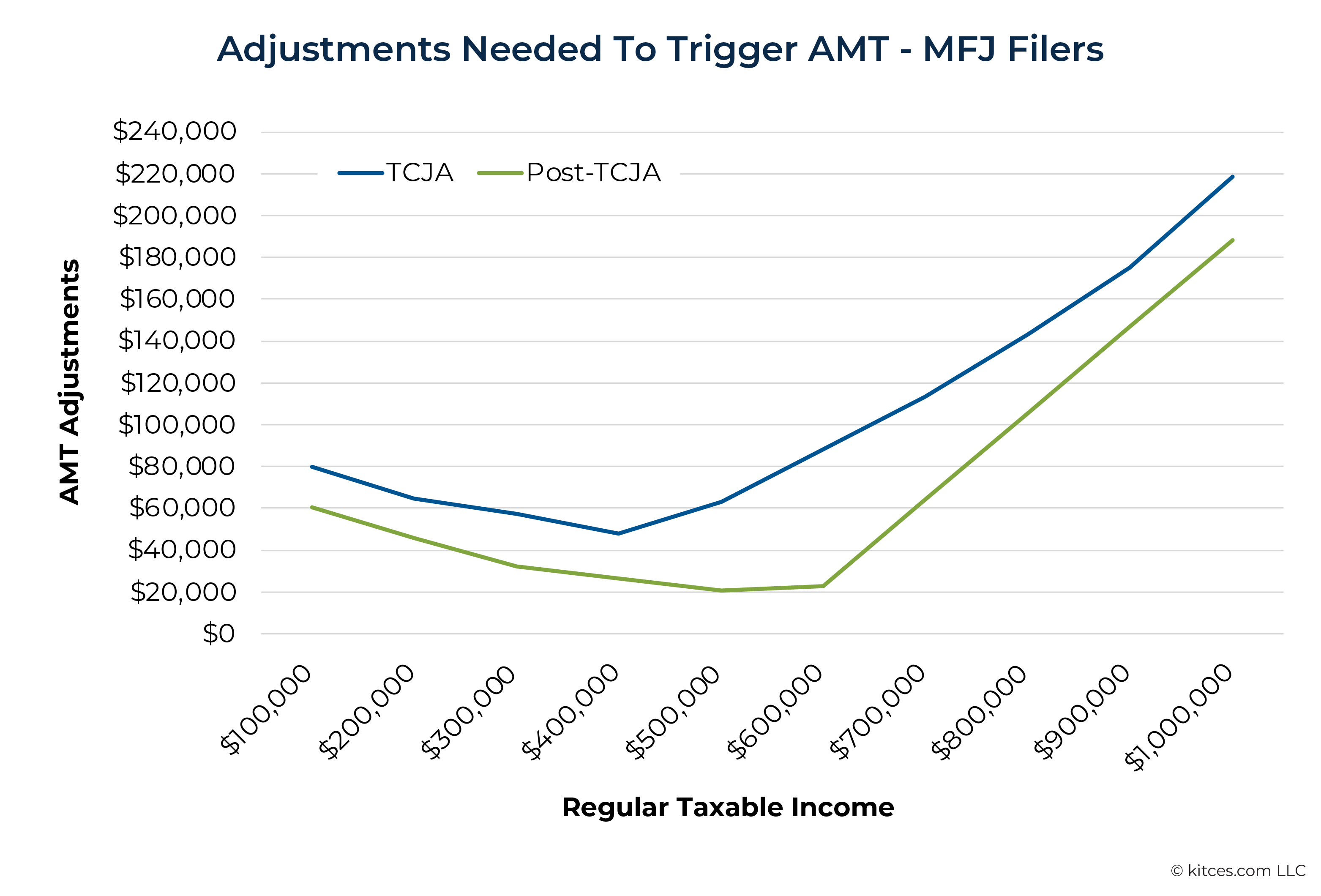

Similarly, for married filers, the amount of AMT adjustments needed to trigger AMT exposure will be lower after TCJA's expiration, particularly for those earning $400,000–$600,000 in regular taxable income. While couples in that range would have needed between $50,000 and $100,000 in AMT adjustments to exceed their regular tax liability under TCJA (the blue line), they will only need $15,000–$20,000 in adjustments after TCJA's sunset (the green line).

Planning For TCJA Sunset Changes

Putting it all together, the following seems to be true about how taxpayers will be impacted by AMT after TCJA's planned expiration in 2025:

- Single filers with $100,000–$500,000 of regular taxable income, combined with more than $40,000 (on the lower end of the income range) to $20,000 (on the higher end of the range) of AMT adjustments like state and local tax payments, personal exemptions, and miscellaneous itemized deductions, will most likely need to pay AMT after TCJA sunsets in 2026.

- Married families with $200,000–$600,000 of regular taxable income, combined with more than $40,000 (on the lower end of the income range) to $20,000 (on the higher end) of AMT adjustments, will also be likely to owe AMT after TCJA sunsets.

- Households in high-tax states and/or with high property taxes, as well as those with multiple dependents (i.e., more personal exemptions), will be much more likely to pay AMT starting in 2026.

- For households that do owe AMT, the 'bump zone' of income where the AMT exemption phases out moves much lower after TCJA expires, meaning that single filers with about $150,000–$420,000 in AMT income, and married filers with $200,000–$620,000 in AMT income, will effectively have a 32% or 35% marginal tax rate on all of their income in that range.

- Households with over $600,000 in regular taxable income will be less likely to owe AMT (though still likelier than they are today), since the reinstated 39.6% top marginal rate will increase the odds that their regular tax will be higher than AMT.

- Those with unused AMT credit carryovers will find it harder to use them after TCJA sunsets, since it's more likely that they will either owe AMT (and not be able to use any of the carryover) or have a smaller difference between regular tax and AMT, reducing the amount of credit they can apply each year.

Of course, the caveat in all these cases is that it's possible that TCJA won't expire as scheduled, but will be extended or amended by Congress between now and the end of 2025 – which leaves some uncertainty around planning for the AMT implications of TCJA's sunset.

However, as the above points make clear, it's vastly more likely that taxpayers will owe more AMT after 2025 – or, at the very least, the same amount of AMT if TCJA is extended – than it is that they'll owe less AMT. Which makes sense, since very few people owe AMT under TCJA in the first place. This narrows the range of planning opportunities to strategies that can help clients either avoid becoming subject to AMT in the future or minimize the impact of AMT if they're already likely to be subject to it.

Proactively Avoiding AMT Exposure

It's not always possible to avoid AMT – for example, someone with moderately high income, high state and local taxes, and multiple dependents might only be able to avoid it by moving to a lower-tax state. However, certain factors driving AMT exposure are more controllable, the most common of which is the timing of exercising Incentive Stock Options (ISOs) granted by an employer. In these cases, it's possible to estimate the effect of exercising the ISOs before or after TCJA's expiration for AMT purposes.

For instance, because AMT exposure is so limited under TJCA, a person might be able to exercise some or all of their ISOs before 2026 without owing any AMT, which means they'd be able to purchase the underlying company shares without triggering additional (immediate) tax.

Example 3: Margot is a single filer who earns $500,000 in salary and pays $35,000 in state and local taxes.

Her employer granted her 20,000 ISOs with an exercise price of $5 per share and a fair market value of $10 per share. If she exercises the options, she would have an AMT adjustment for the unrealized gain of 20,000 × ($10 – $5) = $100,000.

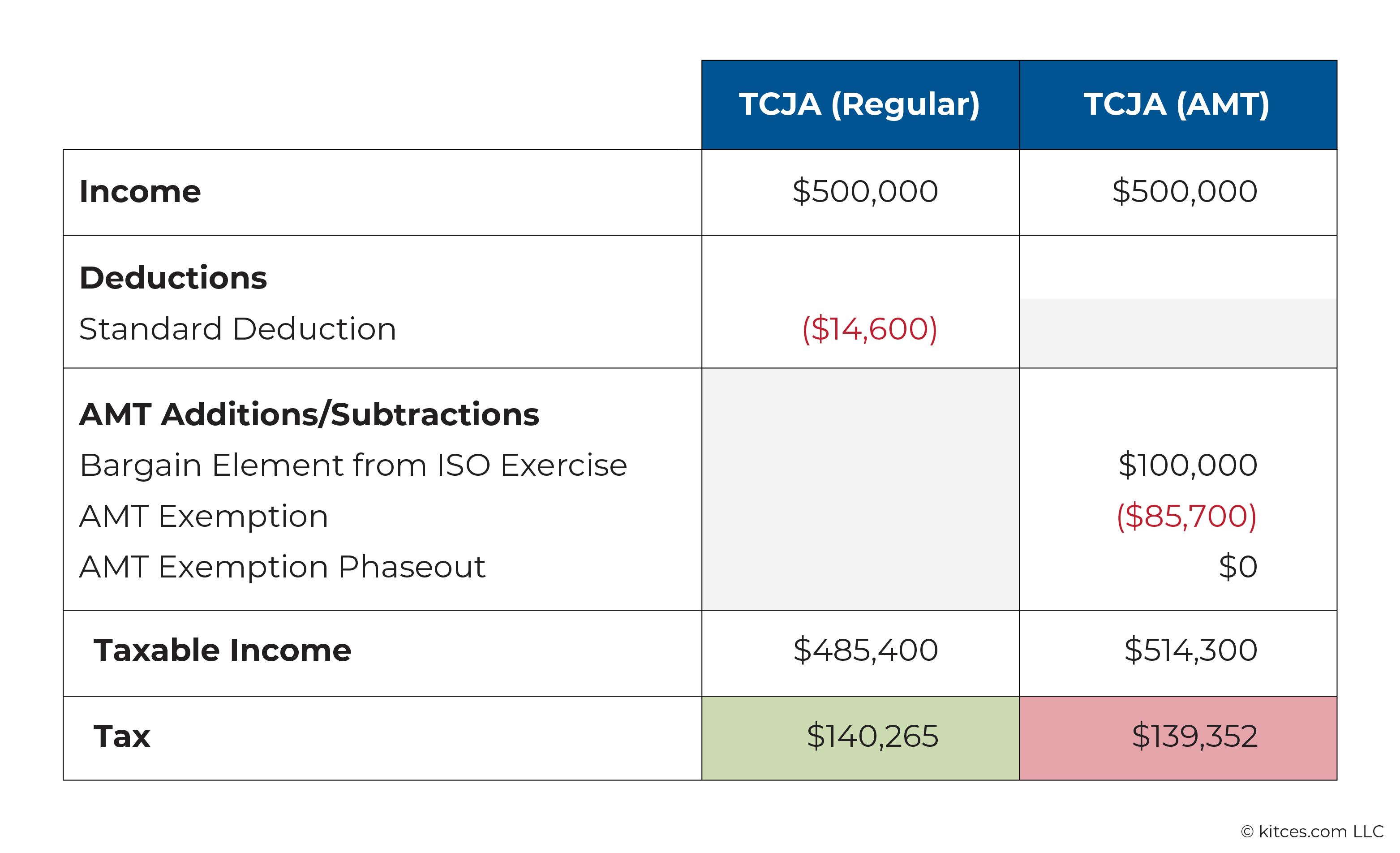

If Margot exercised her options this year under the TCJA rules, her tax calculations for regular tax and AMT would be as follows:

As the calculation shows, the regular tax calculation (which doesn't include income from the ISO exercise) is higher than the AMT (which does include the ISO income). So the entire ISO exercise can be done without incurring any AMT.

However, if a person with ISO compensation waited until after TCJA expires to exercise the options, they might be much more likely to owe AMT on the transaction – which means they'd need to have funds available (or be able to borrow funds) to pay the tax without selling the employer's shares themselves. If an individual's AMT exposure is likely to change after TCJA expires, they may want to accelerate any income or deductions that would be treated as AMT adjustments and result in more AMT exposure in the future.

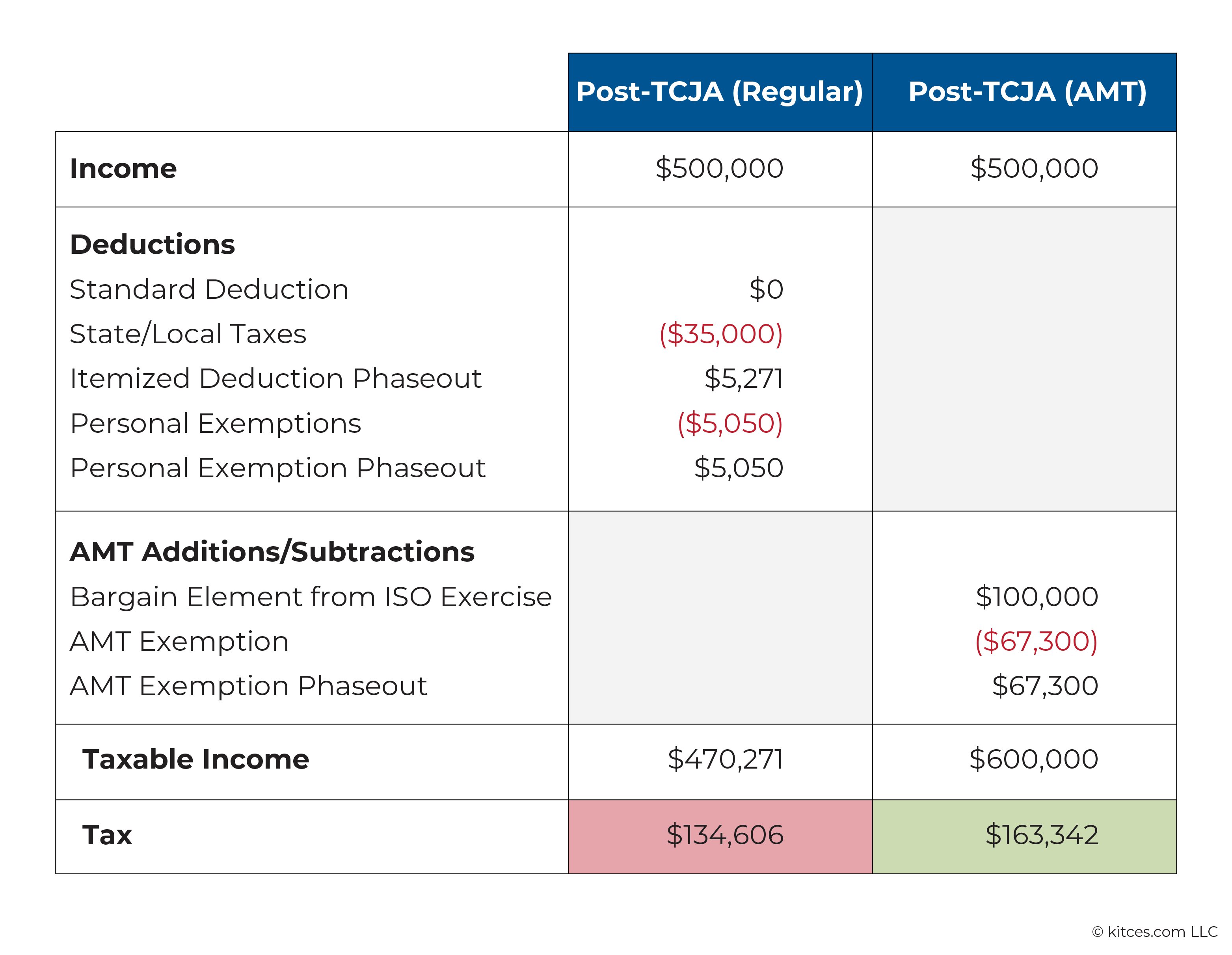

Example 4: If Margot, from the previous example, waited until after the TCJA sunset to exercise her shares, the tax calculations using post-TCJA tax brackets and deduction/exemption rules would be as follows:

The entire transaction would be subject to AMT at the top (28%) marginal rate, and Margot would be required to come up with $28,000 to pay the additional tax without liquidating the employer's shares, which triggered the AMT to begin with.

It's worthwhile, then, to look for opportunities to exercise ISOs without triggering AMT before TCJA sunsets, even if it's 'just' enough to push the AMT calculation up to the point where it's nearly equal to – but not more than – the regular tax, so the exercise won't create AMT exposure after TCJA expires.

Minimizing AMT For Those Expected To Be In The AMT 'Bump Zone'

The second planning opportunity, for those who are already subject to AMT, is using today's higher AMT exemption and lower phaseout thresholds to minimize the actual amount of AMT owed.

Recall that after TCJA's sunset, the AMT income thresholds at which the AMT exemption is phased out shift down dramatically, creating a 'bump zone' within the threshold range where any extra income is effectively taxed at 32.5% and 35%. For households that expect to be subject to AMT after TCJA expires, and whose income is projected to fall within the bump zone, it could make sense to accelerate income to be taxed now at their current marginal rate (as long as that rate is lower than 32.5%) rather than being taxed at the higher 'bump zone' rate after 2025.

Even if accelerating income incurred some AMT now, it still might be beneficial to do so if that income were to fall below the current bump zone and be taxed at 'only' 26%/28% instead of at 32.5%/35% after TCJA expires.

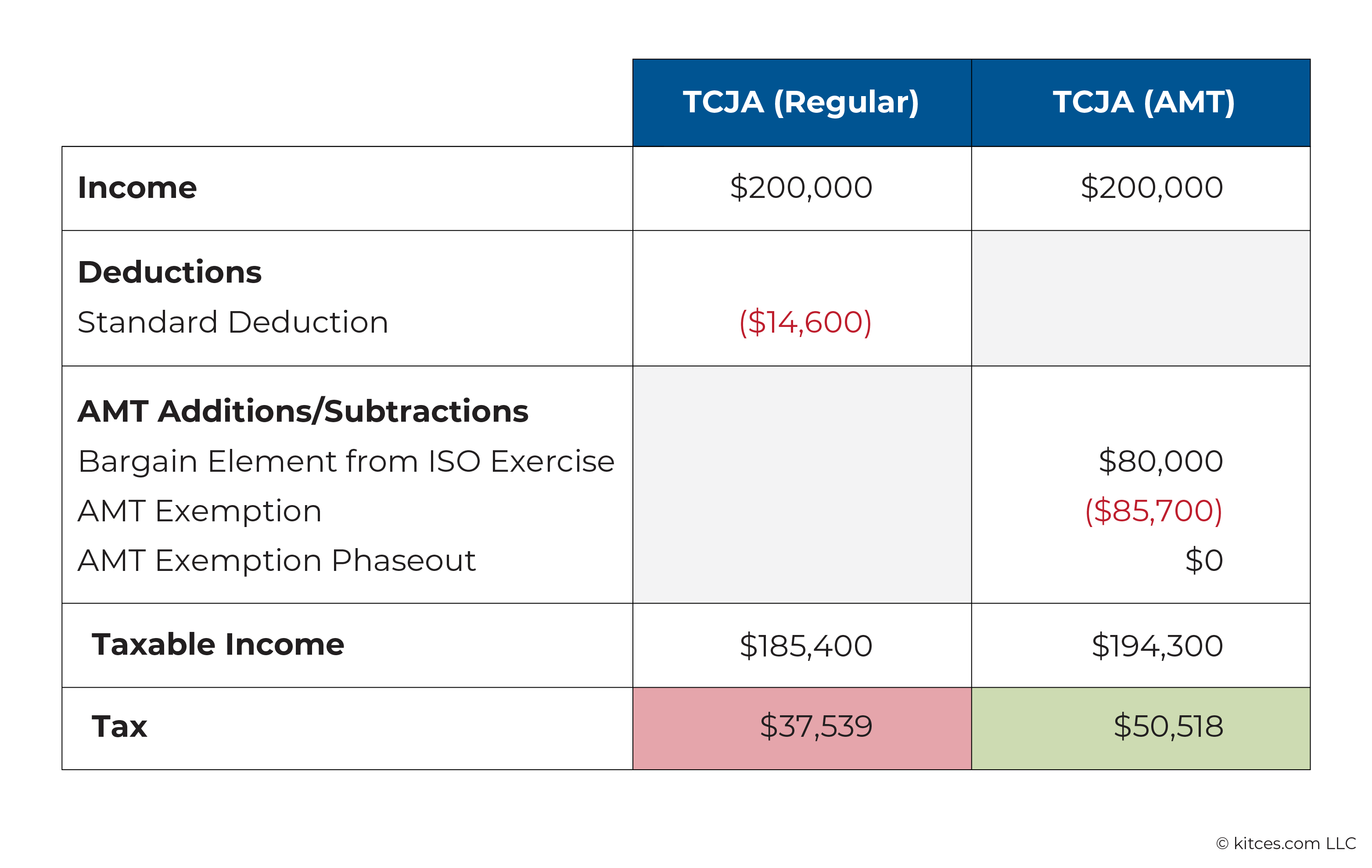

Example 5: Chas is a single filer who takes the standard deduction and earns $200,000 in salary. His employer grants him 100,000 ISOs with an exercise price of $2 and a fair market value of $10. If Chas exercises the options, he will have an AMT adjustment for the unrealized gain of 100,000 × ($10 − $2) = $80,000.

If Chas exercises the ISOs before TCJA expires, he will owe AMT this year in the amount of $50,518 − $37,539 = $12,979, as shown below.

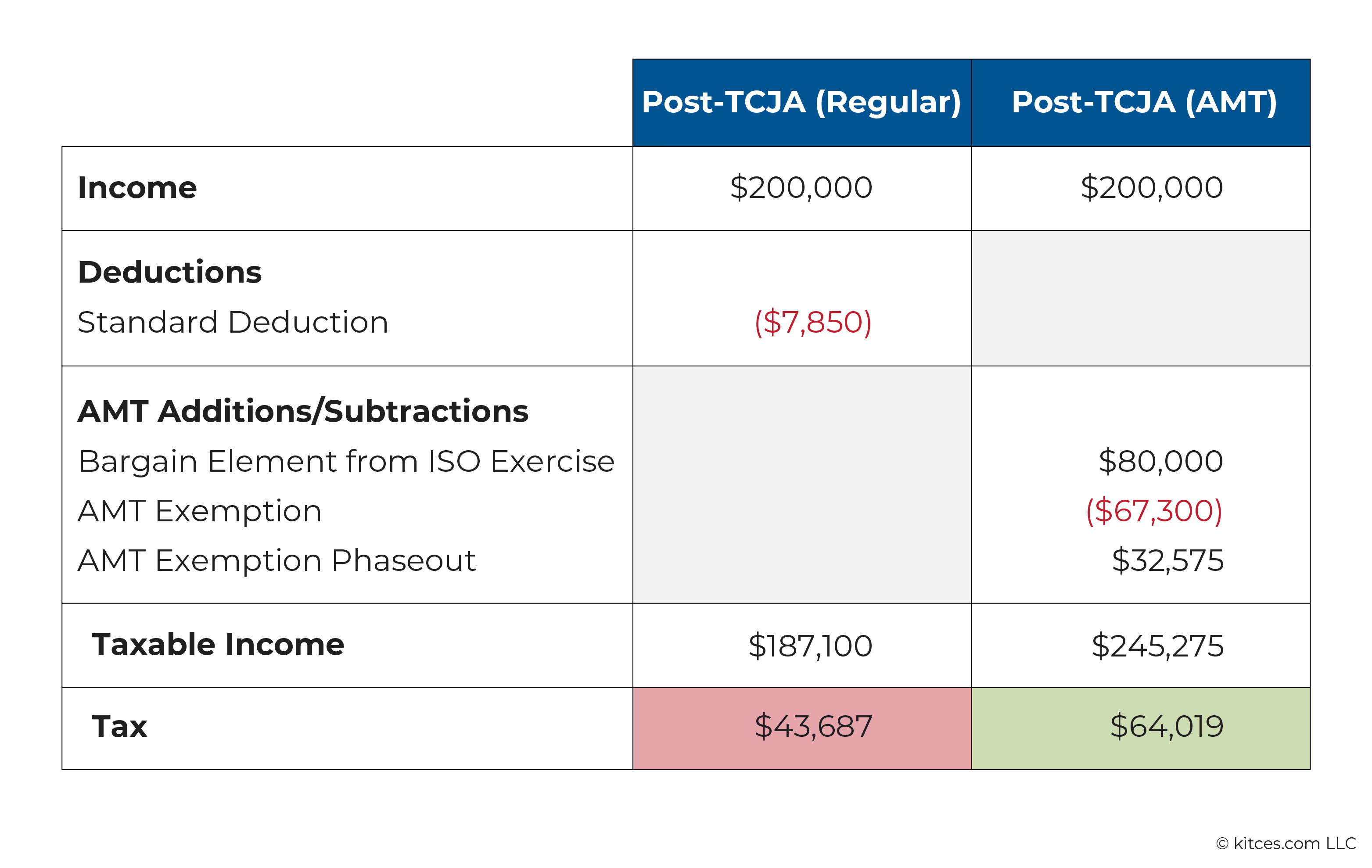

However, if Chas waits until TCJA expires, the income adjustment from exercising his shares would cross him into the new, lower AMT bump zone, causing $32,575 of his AMT exemption to phase out. Combined with the lower overall exemption post-TJCA, he would now owe $64,019 − $43,687 = $20,332 of AMT.

If Chas exercises the ISOs now, he'll need to find outside funds to pay the $12,979 of AMT he incurs – however, if he waits until after TCJA expires, he'll have to come up with even more to pay the higher tax. Overall, he'll save $20,332 – $12,979 = $7,353 in AMT by taking advantage of the more favorable AMT exemptions and phaseout thresholds under TCJA.

There are 2 groups of taxpayers who, conversely, may not want to accelerate AMT income.

The first includes those whose AMT income falls within the current AMT bump zone, which, as noted earlier, is at a higher income threshold than the post-TCJA bump zone. In that case, it might be better to delay income until after TCJA's sunset, since it's likely to fall above the post-TCJA bump zone. In other words, rather than being taxed at 35% today, it would only be taxed at the top nominal AMT bracket of 28% after TCJA's expiration.

Another group of individuals who may not want to accelerate AMT income includes those who may still have unused AMT credit carryovers. In this case, it might be best for them to keep AMT income to a minimum to use up as much or all of the credit as possible, since after TCJA expires, it may not be possible to use any credit if they become subject to AMT again!

Among the many (many) changes that TCJA's planned sunset would bring about, AMT's return to prominence has been one of the least-covered in the media, despite having some of the most widespread potential effects among clients of financial advisors. And because TCJA has been in effect since 2018, many clients who have reached various life milestones since then – like earning higher incomes, buying property, and having kids – might be surprised to find themselves owing AMT for the first time in 2026.

For financial advisors, then, there's value in planning to help clients avoid AMT when possible – but that might only be an option in certain instances (like when a client can decide whether to exercise ISOs pre- or post-TCJA sunset). In other cases where it might not be possible to avoid AMT, advisors can at least help clients understand when they might owe AMT after TCJA's expiration, so they can prepare (e.g., by adjusting withholdings or making estimated tax payments) and avoid any surprises when it's time to file the first post-TCJA return!

Leave a Reply