Executive Summary

Traditionally, the challenge in using a 529 plan to save for higher education expenses has been figuring out how much to save to cover the beneficiary's college costs without overshooting and saving more in the 529 plan than is actually needed. Because while 529 plans' combination of tax-deferred growth on invested funds and tax-free withdrawals for qualified education expenses (plus many state-level tax deductions or credits on 529 plan contributions) make it a powerful savings vehicle for college or graduate school expenses, the flip side is that any non-qualified distributions are subject to income tax plus a 10% penalty tax on the growth portion of the distribution. And so the conundrum of people with "too much" savings in their 529 plan – either because they overestimated how much they needed to save, or because they chose a different path entirely that didn't involve going to college – has been how to get funds out of the plan without sacrificing a large part of their value to taxes and penalties.

The Secure 2.0 Act passed in 2022 provided a new 'escape valve' for individuals who, for whatever reason, found themselves with more funds in their 529 plan than they could use on qualified higher education expenses. The new law created the ability for a 529 plan beneficiary to roll funds over tax-free from a 529 plan to a Roth IRA, subject to several key limitations: The 529 plan must have been maintained for at least 15 years, the amount of the rollover cannot exceed the IRA contribution limit for that year, the rollover must be made using funds that have been in the 529 plan for at least 5 years, and the maximum lifetime that a beneficiary can roll over in their lifetime is $35,000.

Because of the strict limitations on when and how the 529-to-Roth rollover can be done, it has limited usefulness as a planning tool beyond its intended purpose of giving individuals with overfunded 529 plans an opportunity to reallocate some of those funds tax-free towards their retirement savings. Similarly, the $35,000 lifetime rollover limit means that it can't be used by parents or grandparents to gift huge amounts of tax-free dollars to their heirs, since anything beyond that lifetime limit would still need to either be used on qualified educational expenses or be subject to taxes and penalties as a non-qualified distribution.

Even so, 529-to-Roth rollovers can still be worth incorporating into college and estate planning as a way to gift beneficiaries the "option" of putting up to $35,000 towards their retirement savings. In other words, families who want to give their kids a head start on their career and life path (but don't want to simply give no-strings-attached cash) can now consider 529 plans as a way to provide a boost not only to their education savings, but also to their retirement savings.

The key point is that while the new 529-to-Roth rollover rules may be limited in terms of how much wealth they can move into tax-free retirement funds, they can still provide real benefits – both in their intended purpose as an escape valve for people who can't or won't use all of the funds in their 529 plan for qualified education expense, and in the symbolic significance of contributing funds to a child or grandchild that can be used for education, retirement savings, or both!

For a generation of college students, 529 plans have represented one of the most, if not the most, effective methods of saving for higher education expenses. 529 plans allow funds to be contributed on behalf of a beneficiary and then invested so that those funds – along with any investment growth – can later be withdrawn tax-free to pay for qualified educational expenses (tuition, books and supplies, and room and board for at least half-time students at an eligible postsecondary school, up to $10,000 in tuition at a private elementary or secondary school, and/or up to $10,000 in eligible student loan repayments). Which means that a parent, grandparent, or other benefactor who establishes and contributes to a 529 plan immediately after a child is born can take advantage of 18 years (give or take) of tax-free growth until any of the funds are needed to pay for college costs.

Furthermore, although 529 plan contributions aren't tax-deductible at the Federal level, 37 states offer some form of state tax deduction or credit on 529 plan contributions, offering further tax benefits for residents of those states. The ability to get a tax-advantaged head start on college savings for the younger generation has meant that, as tuition and other costs of higher education have skyrocketed over the last 20 years, the benefits and importance of 529 plans have multiplied in kind.

The Dilemma Of 'Too Much' 529 Plan Savings

The major caveat to 529 plans is that there are restrictions on using plan funds for any purposes other than qualified educational expenses. Although the amount of the original contribution(s) can be withdrawn tax-free for Federal tax purposes (since it was not tax-deductible to begin with), the amount of any growth on those contributions is taxable when it is withdrawn for non-qualified purposes.

Furthermore, an additional 10% penalty tax applies to any non-qualified distribution from a 529 plan, with only a handful of exceptions (upon the death or disability of the account beneficiary, when the beneficiary received tax-free scholarships or grants from certain sources, when they attend a U.S. military academy, or when they also claim the American Opportunity or Lifetime Learning tax credits).

The restrictions on 529 plan withdrawals can cause a dilemma, particularly for those who want to get started on college savings for their children at a very young age in order to get as many years of tax-free growth as possible: What if it turns out that they don't need all of the funds in the 529 plan? Few people are worried about saving too much for college, particularly when advanced degrees are in play as well. But it can happen nonetheless, and in an era when young people are increasingly exploring alternatives to college, such as going into trades that can be highly lucrative without the need for a college degree, it's very possible that a young adult whose relatives have been saving for their college education since they were in diapers may simply decide to forego college altogether – leaving behind a pot of funds that can only be withdrawn at a steep penalty.

Historically, 529 account owners have had a few options to work with in these scenarios, most of which revolve around 529 plan rules that allow account owners to change the plan's beneficiary to any family member of the existing beneficiary. Meaning that, for instance, if one child is the beneficiary of a 529 plan owned by their parents and opts to begin working after high school instead of going to college, but there is a younger sibling who does plan to get a degree, the parents can designate the younger sibling as the new beneficiary of the 529 plan, allowing those funds to be used for their own education.

The account owner could even decide to wait until the next generation comes along; for instance, a parent whose own children don't use up all of their 529 plan funds can simply let those funds stay put until grandchildren arrive, who can potentially use them up. Some parents might even use the change-of-beneficiary rules (and similarly the flexible change-of-account-ownership rules) to create a "Dynasty 529 Plan" to intentionally overfund their children's college savings so they can be passed on to future generations.

And yet, relying on the change-of-beneficiary rules to create an escape valve for an overfunded 529 plan assumes that 1) there even is another beneficiary, either now or in the future, to transfer the funds to (which is no guarantee, since there aren't always going to be siblings or future grandchildren to designate as the 529 plan's new beneficiary); and 2) the 529 account owner is OK with effectively taking away what may be a significant chunk of savings from the original beneficiary and handing it to the new beneficiary, which can conceivably cause family conflict over the perceived fairness of withholding a large gift of funds simply because the intended recipient decided that college wasn't the best option for them (or received a scholarship, chose a less expensive school, pursued an associate's degree, or any number of equally reasonable scenarios that might result in leftover 529 plan funds).

So when planning for their children's or grandchildren's education, 529 plan savers have often taken care not to overfund the accounts to avoid the dilemma of deciding what to do with funds that are left over. Often, they plan on funding less than 100% of the child's education costs via 529 plan funds while making up the remainder from other sources like taxable account funds or student loans. But still, in order to save enough to cover even a moderate portion of the cost of a 4-year degree, it's practically a requirement to start saving for a child's education before they're even capable of having a conversation about what type of education or career path they want to pursue. Which means there's still plenty of anxiety about the specter of unused – and ultimately taxed and penalized – 529 funds.

The SECURE 2.0 Act's New 529-To-Roth Rollover Rules

Recognizing the dilemma faced by families over the penalties for withdrawing leftover 529 plan funds, Congress included a provision in the SECURE 2.0 Act, passed within the Consolidated Appropriations Act in the final days of 2022, that created an additional safety valve for 529 plan funds to be transferred out, tax-free, without requiring them to be used on qualified educational expenses. Namely, Sec. 126 of SECURE 2.0 created the ability for a beneficiary of a 529 plan account to roll over funds, tax- and penalty-free, into a Roth IRA in their name, effectively allowing them to convert at least a portion of their tax-advantaged educational savings into tax-advantaged retirement savings.

When creating the 529-to-Roth rollover provision, however, Congress included some restrictions significantly limiting the benefits that any one person can realize from rolling over their 529 plan into a Roth IRA, presumably to avoid turning 529 plans into a massive backdoor Roth opportunity for high-income earners who would otherwise be forbidden from making Roth IRA contributions.

Specifically, these limitations are:

- The 529 plan must have been maintained for a period of at least 15 years before the date of the rollover;

- The amount of each rollover cannot exceed the aggregate amount of contributions (and earnings attributable thereto) made earlier than the 5-year period before the date of the rollover;

- The amount of each rollover also cannot exceed the IRA contribution limit for that year, minus any amounts that the taxpayer contributed directly to the IRA that year; and

- The maximum amount of funds that a 529 plan beneficiary can roll into a Roth IRA over their lifetime is $35,000.

The first date when individuals could make a qualifying 529-to-Roth rollover was on January 1, 2024.

It's worth digging further into these provisions to clarify potential areas of confusion about executing a 529-to-Roth rollover, as well as highlighting areas that the initial SECURE 2.0 legislation left unclear and, as of this writing, haven't been cleared up by further guidance from Congress or the IRS.

The "15-Year" Rule For The 529 Plan Itself

The SECURE 2.0 legislation is clear that a 529 plan needs to have been "maintained for the 15-year period" prior to rolling funds into a Roth IRA – that is, the 529 plan itself needs to have been in existence for at least 15 years before a 529-to-Roth rollover can be made. However, what isn't clear is whether the person rolling the funds over needs to have also been the beneficiary for all 15 of those years. Which would seem to be an important piece of clarification, given that whether a change of beneficiary restarts the 15-year 'clock' for a 529-to-Roth rollover makes a big difference for 529 plans that have been in existence for more than 15 years but have changed beneficiaries more recently. And yet, neither Congress nor the Treasury Department has issued any guidance to clear up the sparse language of the bill.

For now, then, it's likely safest to only execute rollovers from 529 plans where both the plan and the beneficiary have been in place for at least 15 years. For the rest, it may be best to wait either until those 15-year periods have been satisfied or until more guidance is released. Because while it's possible that the IRS will later create a retroactive safe harbor for individuals who did the rollover before any clarification was issued, it's by no means a guarantee, and a 529-to-Roth rollover that is later deemed impermissible would be subject to taxes and penalties as a non-qualified distribution of 529 plan funds.

The "5-Year" Rule For Contributions To The 529 Plan

This provision has some of the most confusing language in the 529-to-Roth legislation, which stipulates that a rollover cannot "exceed the aggregate amount contributed to the program (and earnings attributable thereto) before the 5-year period ending on the date of the distribution". What it essentially means, however, is that funds contributed to a 529 plan in the last 5 years, and any earnings on those funds, cannot be rolled over to a Roth IRA.

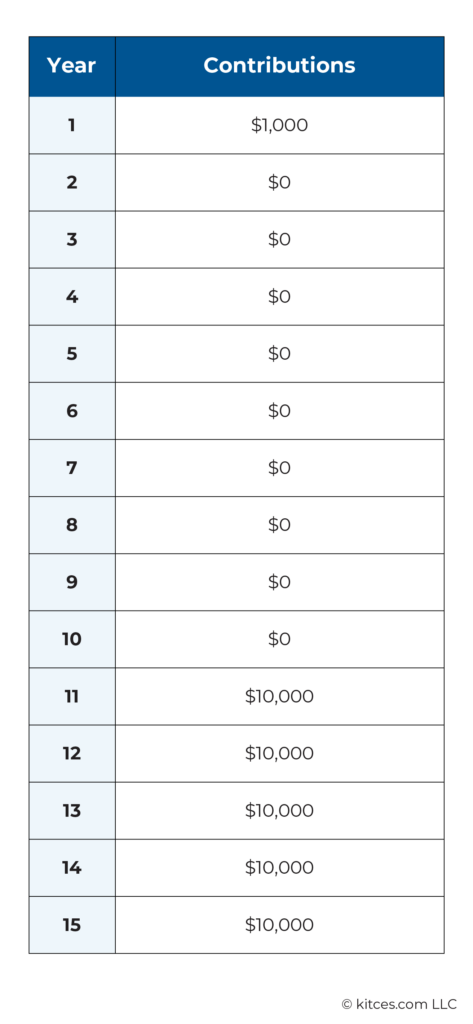

Example 1: Mina is the beneficiary of a 529 plan that has been maintained in her name for the last 15 years. In Year 1 of her plan, Mina's parents contributed $1,000 on her behalf. In Years 11–15, they contributed $10,000/year on her behalf, resulting in the following contribution schedule:

If Mina wanted to make a 529-to-Roth rollover this year (i.e., in Year 15), assuming she meets all the other qualification criteria, she would only be eligible to roll over $1,000 (plus any earnings attributable to that contribution) – that is, the amount of contributions plus earnings that were made earlier than 5 years (i.e., before Year 11) prior to the rollover.

If she wanted to do another rollover next year, however, she would be eligible for a higher amount, because her $10,000 contribution in Year 11 would now be more than 5 years prior to the rollover, and would thus count toward the annual contribution limit.

Notably, what's still uncertain is whether doing a 529-to-Roth rollover in one year would reduce the amount of contributions from earlier than 5 years ago that are available for the rollover. For example, if someone has a total of $1,000 of contributions and earnings from prior to 5 years ago and subsequently rolls over $1,000 into their Roth IRA, would their aggregate amount of contributions made prior to 5 years ago be reduced by $1,000, or would they continue to be able to use that amount next year for the purposes of meeting the 5-year rule (even if all of the remaining funds in the account were contributed less than 5 years ago)?

The question matters because if a person is able to 're-use' old 529 plan contributions to qualify for the 529-to-Roth rollover, they could effectively use the 529 plan as a vehicle for making backdoor Roth contributions by contributing to the 529 plan each year and then subsequently rolling the amount over into a Roth IRA. Except unlike a 'normal' backdoor Roth contribution, there would be no issue with having pre-tax IRA assets making the Roth conversion taxable, which would make the "529 backdoor Roth" strategy useful for individuals with large amounts of pre-tax IRA assets (who happened to also have a 529 plan that had been maintained for at least 15 years and had contributions from prior to 5 years before – so not exactly a wide-ranging planning opportunity, but useful to know for those who met those criteria). And, in any case, the 'door' on this particular backdoor Roth strategy would close after rolling over the lifetime maximum of $35,000, limiting its usefulness as a long-term planning strategy.

How Earned Income Impacts Annual Rollover Limits

At a high level, the amount that someone can roll from a 529 plan into a Roth IRA in a year is limited to the IRA contribution limit for that year (e.g., $7,000 for those under 50 in 2024), plus catch-up contributions ($1,000 for individuals age 50 and over, although SECURE 2.0 indexed that amount to inflation and increased the catch-up contribution to at least $10,000 for individuals aged 60–63 beginning in 2025). However, there are 2 important caveats that apply, both having to do with the income of the person doing the rollover.

The first is that, as when making a normal IRA contribution, an individual needs to have earned income in order to roll assets from a 529 plan into a Roth IRA. The amount they can roll over, effectively, is the lesser of 1) their earned income, or 2) the annual IRA contribution limit (reduced by any other IRA contributions made that year), assuming they meet all other requirements for the rollover.

The second caveat is that, unlike making a normal Roth IRA contribution, where the ability to contribute to a Roth phases out for individuals with higher incomes, there are no income-based phaseouts for a 529-to-Roth rollover.

In other words, while there is a floor on (earned) income that's needed to roll 529 plan funds into a Roth IRA, there is no income cap.

$35,000 Per Beneficiary Lifetime Maximum

The aggregate lifetime limit on 529-to-Roth rollovers is $35,000 per beneficiary, but again, the language of the law leaves some uncertainty on how that limit is applied and will require further guidance from Congress or the IRS. For instance, if an individual is the beneficiary of 2 529 plans – one owned by their parents and another by their grandparents – can they roll over $35,000 from each of them or only $35,000 in total? It's hard to imagine that Congress intended for the limit to apply to any more than once per person, but rather than make that simple clarification in the text, the law's writers left it ambiguous.

It also doesn't appear that the $35,000 lifetime maximum will be indexed to inflation, although Congress or the IRS could decide to do so later on.

Thankfully, there's some time for the IRS to resolve these questions, since the annual limits on rollovers means that it will take several years for anyone to get close to the $35,000 maximum. Still, it's likely best to assume a more conservative position – that each person can roll over no more than $35,000 in their lifetime, full stop, no matter how many plans they are the beneficiary of – until disproven by further guidance.

529-To-Roth Rollovers And Roth IRA Withdrawal Rules

When contributing to or rolling money over into a Roth IRA, individuals need to follow certain rules to avoid being taxed or penalized on subsequent withdrawals from the account. Namely, for a Roth IRA distribution to be considered "qualified" and, therefore, tax-free, it needs to meet 2 separate requirements:

- The distribution occurs on or after the date the IRA owner turns 59 1/2 (or occurs after the death or disability of the owner, or is made for up to $10,000 of first-time homebuyer expenses); and

- The distribution needs to be made at least 5 tax years after the owner makes their first contribution to any Roth IRA.

Notably, while there is a second "5-year rule" that applies to amounts converted to Roth (rather than contributed directly), a 529-to-Roth rollover appears to fall under the rules applying only to contributions. Which means that, if the taxpayer has made any Roth IRA contributions beginning at least 5 tax years before the 529-to-Roth rollover (and is also age 59 1/2 or older), they can immediately withdraw the rolled-over funds as a tax-free qualified distribution.

What isn't clear, however, is what happens if an individual has never contributed to a Roth IRA before rolling funds over from their 529 plan, or if they made their first Roth IRA contributions within 5 tax years of the 529-to-Roth rollover. Does the 5-year 'clock' start when the funds were initially contributed to the 529 plan? Or would they need to wait another 5 years after the rollover (or after their initial Roth IRA contribution) to make a qualified distribution? The IRS will need to weigh in to make it clear when someone over age 59 1/2 can withdraw their rolled-over funds without penalty.

What the text of SECURE 2.0 does make clear is that, in the event of a non-qualified distribution, the principal and earnings of funds rolled from a 529 plan into a Roth IRA are treated in the same way as if they had been rolled over from another Roth IRA, which is to say that the principal of the rolled-over 529 funds (which is the pro rata portion of contributions to the percentage of the total account value of the entire 529 plan) is added to the principal of the existing Roth IRA (if any), and the earnings of the 529 funds are added to the earnings of the Roth IRA.

Any non-qualified distributions from a Roth IRA are made on a first-in, first-out basis, meaning that withdrawals will be treated as tax-free returns of principal first and taxable (and penalized) earnings only after the principal has been fully depleted.

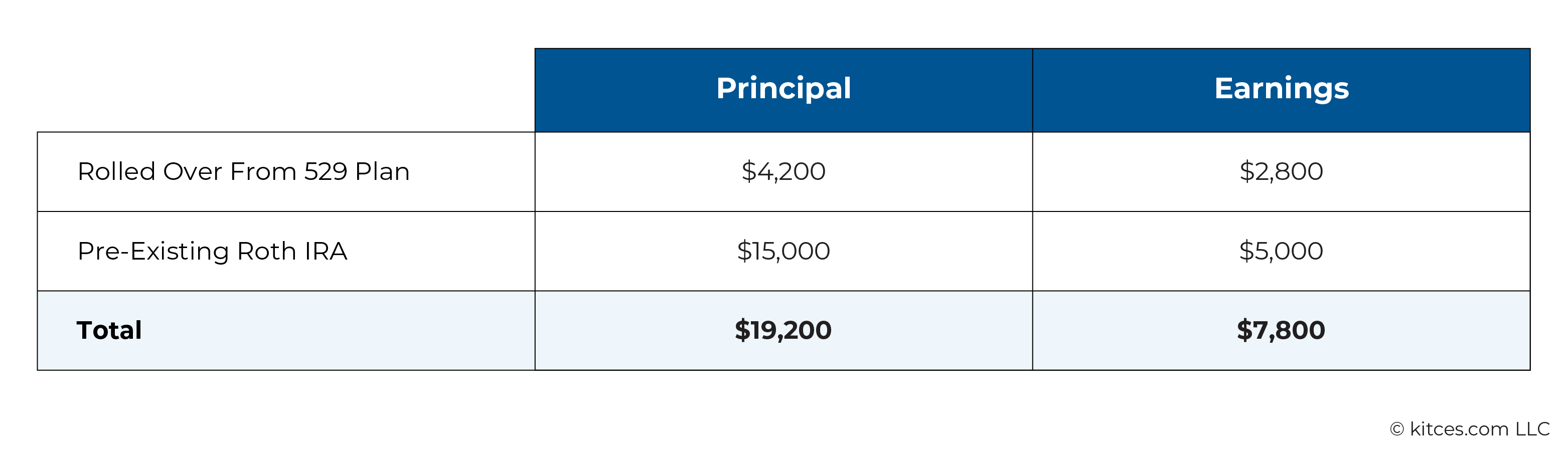

Example 2: Pablo is the 30-year-old beneficiary of a 529 plan with a total value of $10,000, consisting of an initial contribution of $6,000 and earnings of $4,000. After finding out that he meets the qualifications to make a 529-to-Roth rollover, he rolls $7,000 from his 529 plan into his existing Roth IRA, which has a total value of $20,000 consisting of $15,000 in contributions and $5,000 in earnings.

Because his total 529 assets include 60% principal and 40% earnings, 60% × $7,000 = $4,200 of his 529-to-Roth rollover is treated as principal, and 40% × $7,000 = $2,800 is treated as earnings.

These amounts are added to the principal and earnings in his Roth IRA, with the new totals as follows:

Unfortunately, Pablo needs to undergo an expensive medical procedure, for which he needs to withdraw $20,000 from his Roth IRA. Because he is under age 59 1/2, the withdrawal will be treated as a non-qualified distribution, with the principal being withdrawn first and the earnings second.

Because his Roth IRA's principal is now $19,200, all but $800 of his $20,000 withdrawal will be treated as a tax-free return of principal, with the remainder being included in taxable income and subject to a 10% penalty tax.

The bottom line is that, for individuals under age 59 1/2, any amount rolled over from a 529 to a Roth IRA that is subsequently treated as principal within the Roth IRA can be immediately withdrawn tax-free – which makes sense, given that the main purpose of creating the 529-to-Roth rollover in the first place was to 'unlock' unused 529 funds that would have otherwise been penalized on withdrawal. Now, at least the principal amounts can be tapped before retirement, although the earnings will still have to wait until age 59 1/2 to avoid tax and penalties.

State Tax Implications Of 529-To-Roth Rollovers

Although rolling funds from a 529 plan to a Roth IRA can be tax-free for Federal tax purposes as long as the requirements are met as described above, the same isn't always true when it comes to state income tax. While many states do appear to conform to the Federal law treating 529-to-Roth rollovers as a qualified, tax-free distribution, other states currently treat the rollover as a non-qualified distribution subject to state income tax.

A full breakdown of the state tax implications of 529-to-Roth rollovers is a topic for a later article, but for now, it's at least worth noting that states that offer tax deductions or credits for 529 plan contributions may recapture some of those tax breaks on funds rolled over to a Roth IRA.

According to one site that tracks state conformity to the Federal 529-to-Roth rollover rules, there are currently 32 states that treat rollovers to a Roth IRA as a qualified tax-free distribution (including the 9 states that have no state income tax), 11 states where rollovers to a Roth IRA is treated as a non-qualified expense subject to recapture of any tax deductions or credits previously taken and/or taxes on the earnings portion of the rollover (with California adding on an additional 2.5% penalty on earnings), and 7 states plus Washington D.C. that either have not made their stance clear yet or are still pending a final decision on their conformance to Federal tax law.

The key point is that while some 529-to-Roth rollovers may be tax-free at both the Federal and state level, individuals in some states – particularly in states where they received a tax deduction or credit for originally contributing to the 529 plan – will need to factor in the state tax implications of the rollover. Notably, this includes many of the higher-tax states like California, New York, and Massachusetts, so some of the individuals who already pay the most in state tax will have the biggest state tax implications of a 529-to-Roth rollover.

How Useful Are 529-To-Roth Rollovers As A Planning Tool?

Although Congress's intent in creating the 529-to-Roth rollover was clearly to create a safety valve for moving unneeded funds from a 529 plan without incurring taxes and penalties, as soon as the new rules were announced, tax planners began to explore opportunities to create tax savings in other ways. Could the 529-to-Roth rollover rules provide ways for clients to create significant tax-free wealth for their children – or even for themselves?

Right off the bat, it's clear that as a method of moving significant amounts of funds into a tax-free Roth account, the 529-to-Roth rollover pales in comparison to other strategies. Much of this is because of the comparatively small annual rollover limit (up to $7,000 in 2024, or $8,000 for those eligible for catch-up contributions) and lifetime rollover limit ($35,000) on 529-to-Roth conversions.

By contrast, a "mega-backdoor Roth", for example, can move up to $69,000 into Roth savings in one year by taking advantage of the ability to make after-tax 401(k) plan contributions up to the annual qualified plan contribution limit and subsequently convert them to Roth. And for those without the ability to make after-tax 401(k) plan contributions, even a 'standard' backdoor Roth strategy involving making nondeductible IRA contributions and subsequently converting them to Roth usually makes more sense than rolling over funds from a 529 plan despite also being subject to the annual contribution limits on IRAs, since 1) it doesn't require maintaining the account for 15 years before the rollover, and 2) it doesn't have any lifetime limit on the amount of rollovers one can make.

So, what planning opportunities are there?

The Mega-Delayed Backdoor Roth

Some people have considered the possibility of using the 529-to-Roth rollover rules as a way to effectively pre-fund a series of future Roth contributions – that is, to make a lump-sum contribution into a 529 plan in one's own benefit today with the sole purpose of converting the funds to Roth after hitting the 15-year requirement, with the idea that letting the funds grow tax-free in the 529 plan (rather than in a taxable brokerage account, where taxable interest, dividends, and realized capital gains are taxed annually) can give the savings a greater boost. It could also make some sense for individuals with high amounts of pre-tax IRA assets but who don't currently have a 529 plan that meets the "15-year" and "5-year" rules.

While this makes sense in theory, running the numbers shows that there's simply not that much of a benefit to the 'mega-delayed backdoor Roth', given the $35,000 lifetime maximum rollover limit.

Let's say that a person wanted to accumulate $35,000 in a 529 plan 15 years from now in order to roll the maximum amount over to a Roth IRA. Using a TVM calculation and assuming an 8% net rate of return, they'd need to contribute $11,033 to the 529 plan today to reach $35,000 in 15 years.

If they saved the money in a taxable account instead of a 529 plan, they would need to pay tax on the gains realized. Assuming a 25% combined Federal and state tax rate on capital gains, they would need to save $13,312 today in order to have $35,000 in after-tax savings in 15 years.

In other words, the difference between present-day contributions – $13,312 for the taxable account and $11,033 for the 529 – means there is a present-day savings of $2,279 by funding future Roth IRA contributions via 529 versus a taxable account. And that's in a best-case scenario with someone in a high capital gains tax bracket; for someone in the 15% or 0% bracket or in a tax-free state, the difference would be even smaller. While there's not zero value in pre-funding future Roth contributions via a 529 plan, it may not be exactly worth the extra hassle of opening and maintaining a 529 account for 15 years.

The Retirement Savings "Option" In An Educational Savings Account

One way to think about the new 529-to-Roth rollover rule is that it gives beneficiaries an option to convert a portion of their education savings into retirement savings. In other words, while a retirement account such as an IRA is only a retirement account (with the only exceptions being in certain extreme cases like death and disability), a 529 plan now has the ability to hold savings that are earmarked both for educational savings and retirement (or at least to be a parking spot for funds that can be converted into retirement savings, up to the $35,000 lifetime limit).

For families concerned about giving their kids a head start on their role in society – which, after all, is effectively what education savings are all about for many people – the emergence of the 529-to-Roth rollover option has significance beyond being simply a safety valve for unused educational savings. This option also offers a building block on top of those educational savings to also give their kids a boost on their future retirement savings with the added benefit that, rather than being completely unrestricted as gifts in cash or securities would be for a recipient over age 18, those funds would still have a forward-looking purpose as savings for the future.

A parent or grandparent may not want to simply give their children or grandchildren cash that they can do anything they want with. Instead, they might prefer to provide a solid foundation for them in the future – and perhaps, at the same time, make it possible to get an internship, start a business, or otherwise invest in their own careers without worrying about sacrificing their retirement stability to do so. In this case, the 529-to-Roth rollover could be worth considering (if not because the dollar amounts involved are huge, then because of the support for future wealth-building it symbolizes).

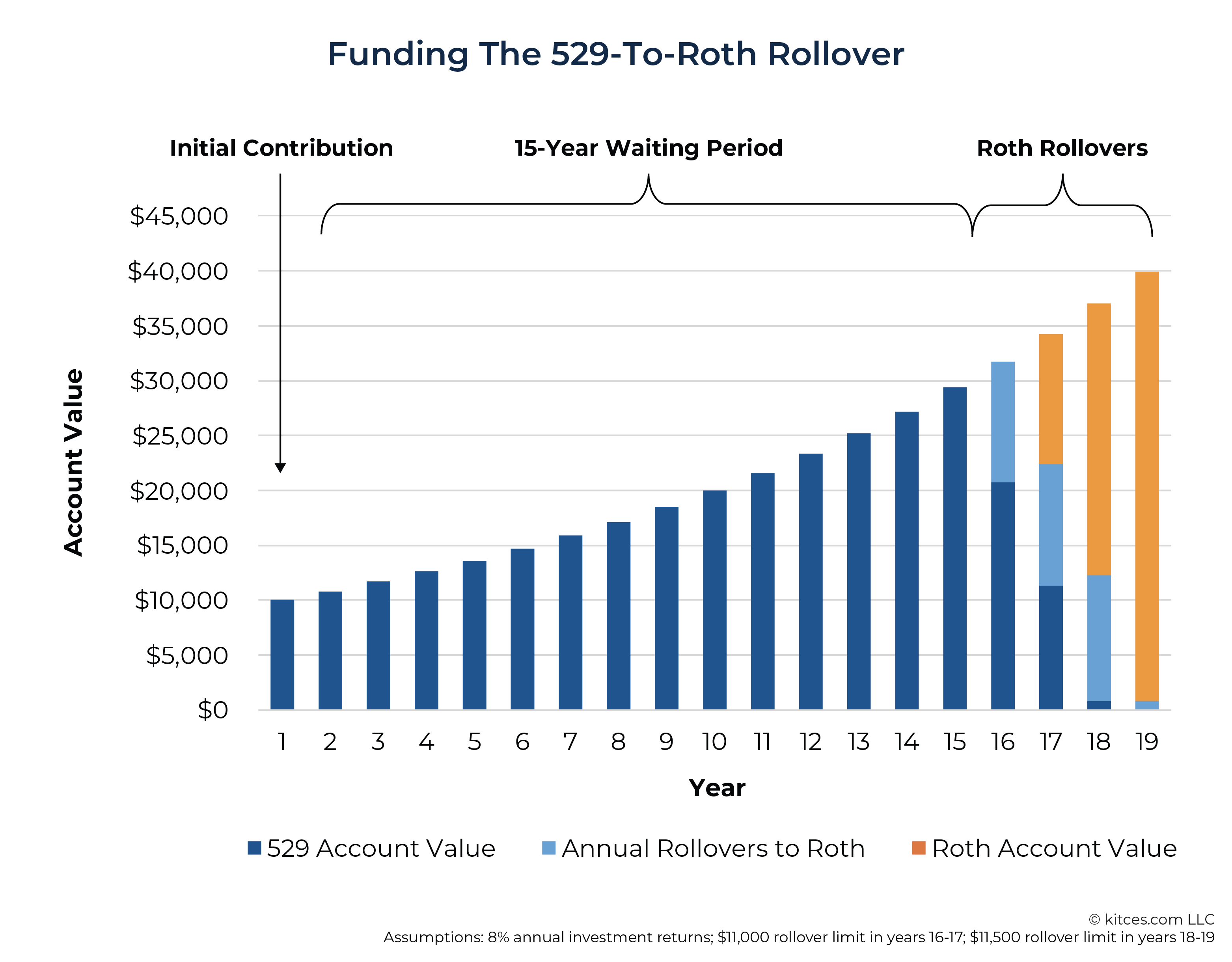

As shown below, it's possible to see how $10,000 contributed to a 529 plan today and achieving an 8% annual rate of return would be enough to fund a series of 529-to-Roth rollovers that would nearly reach the $35,000 lifetime limit. At the end of year 15 (i.e., the end of the "waiting period" during which the 529 plan needs to be maintained before any 529-to-Roth rollovers can be done), the initial $10,000 contribution has grown to $29,372. Assuming a 3% inflation rate during that period, the IRA contribution limit would be $11,000 in years 16–17, and $11,500 in years 18–19, representing the maximum amount of funds that can be rolled over during each year.

Since the funds in the 529 plan continue to grow, the total amount transferred to the beneficiary's Roth IRA ends up being $11,000 (year 16) + $11,000 (year 17) + $11,500 (year 18) + $853 (year 19 – the last remnant of funds left in the 529 plan) = $34,353. At the end of 19 years, the total savings – now fully within the Roth IRA – will have reached $39,960.

A parent or grandparent who wants to take full advantage of the 529-to-Roth "option", then, can contribute more on top of what they were already planning to put into the 529 plan for education expenses alone. At the earliest extreme, the parent or grandparent of a newborn can contribute around $10,000 to a 529 plan with the baby as the beneficiary, and by the time the child turns 16 (when the 529 plan has been maintained for over 15 years), the child would be able to start rolling funds into their own Roth IRA. However, the caveat is that if the child doesn't have any earned income once their 529 plan hits the 15-year mark, they still won't be able to make any rollovers until they start working. So it may make more sense to wait until a child is around 7 years old to start contributing for 529-to-Roth purposes, since they'll be more likely to be earning enough income to make a 529-to-Roth rollover at age 22 than they are at age 15.

The additional consideration, of course, is that overfunding the retirement savings part of the 529 plan beyond the $35,000 lifetime rollover limit results in the same issue as has always been the case with overfunded 529 plans, namely that there's no way to get those funds out of the plan other than to take a non-qualified distribution and incur the resulting taxes and penalties. Future versions of Congress may raise the lifetime cap on rollovers in the future, but for now, it's better to err on the side of slightly undershooting the $35,000 limit than going over – unless there's another relative who can be named a beneficiary to receive the excess funds, either for educational savings or as a recipient of their own 529-to-Roth rollover.

The main intent of the new 529-to-Roth rollover rules is to allow some leeway for people who, for any number of reasons, can't or won't use all the funds in their 529 plan for qualified education expenses to instead direct those funds towards their retirement savings while keeping their tax-free status. And while the restrictions on when and how rollovers can be done and the $35,000 lifetime cap on total rollovers put a limit on how financially impactful the planning opportunities around 529-to-Roth rollovers can be, there's a symbolic significance to being able to contribute funds that can be used for either education or retirement savings, which may make them worth considering for parents or grandparents fortunate enough to be able to make such contributions.

For financial advisors, then, it's worth discussing 529-to-Roth rollovers with clients not only in the context of education planning (e.g., as a consideration for deciding how much of a child's college expense to fund and what to do with any funds that might be unused), but also around planned gifts from one generation to the next. For parents or grandparents who want to use their wealth to increase opportunities for those that come after them, contributing to a 529 plan can help ensure that, if the funds aren't going towards the beneficiary's college education, they're at least going toward securing their financial future (where they may be able to pass it on to the generation after them)!

Leave a Reply