Executive Summary

Most taxpayers are eager to claim any and all tax deductions that they can, yet the reality is that with the newly expanded Standard Deduction under the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) of 2017, as many as 90% of households will no longer itemized deductions at all… which effectively means many tax deductions that were recently popular, from state and local income and property taxes, to mortgage interest, and even charitable contributions, may actually be worthless in the future.

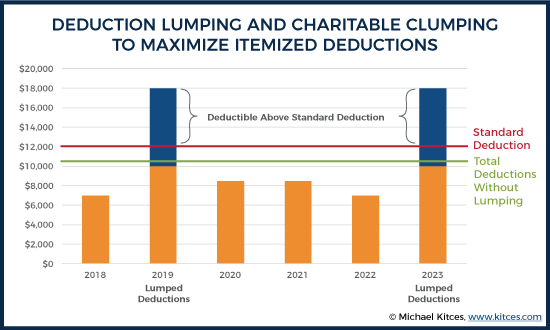

For those who are at least close to the threshold where itemized deductions exceed the Standard Deduction, though, it may be appealing to deliberately time and “lump together” available itemized deductions (e.g., shifting the timing of state estimated tax payments, and property taxes where permitted), or even clump charitable contributions into a donor-advised fund, such that the combined lumped-and-clumped deductions do exceed the Standard Deduction… at least every few years.

Ironically, those who already have substantial itemized tax deductions – especially including the mortgage interest deduction – may already have more than enough deductions to pursue such strategies. And with the new $10,000 cap on SALT (State And Local Tax) deductions, many households will struggle to itemize at all (especially married couples). Nonetheless, for some, the opportunity to lump and clump deductions together – especially for those that have other (appreciated) assets available to front-load charitable contributions into a donor-advised fund (and save on capital gains taxes in the process) – can produce a material tax savings in the future!

Clearing The Hurdle Of The Standard Deduction

Congress allows taxpayers to claim various tax deductions that will reduce their taxable income. In some cases, the deductions are intended as tax incentives to encourage certain behaviors (e.g., deductions for charitable giving); in other cases, they’re tax subsidies to mitigate the net after-tax cost (such as the deduction for mortgage interest or various miscellaneous itemized deductions).

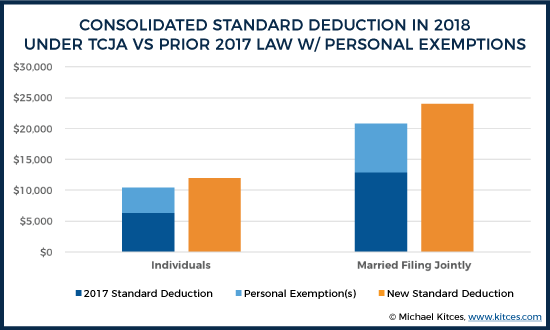

To simplify the tax filing process, all taxpayers have the option to simply claim a “Standard Deduction” – literally, a standardized dollar amount, depending on your tax filing status, that is available to virtually everyone. In 2017, these thresholds were $6,350 for individuals, and $12,700 for married couples (plus an additional standard deduction for those who are blind, or age 65 or older).

To the extent that a household has more individually itemized deductions than “just” the standard deduction, it’s permitted to claim the total of those itemized deductions on Schedule A. Otherwise, the household simply claims the Standard Deduction. In practice, IRS data shows that approximately 70% of all households just use the Standard Deduction, because their itemized deductions aren’t enough in the aggregate to clear the hurdle of being more than the Standard Deduction in the first place.

However, under the recent Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) of 2017, the Standard Deduction was substantially increased for 2018 and beyond, as a part of consolidating together the $4,050-per-individual Personal Exemption and the Standard Deduction. Going forward, the new Standard Deduction amounts are $12,000 for individuals, and $24,000 for married couples.

In addition, TCJA also curtailed a number of previously-popular itemized deductions. Starting in 2018, the maximum deduction for all state and local taxes paid (including state and local income taxes, and property taxes) is capped at a maximum of $10,000. In addition, the mortgage interest is deductible on only the first $750,000 of acquisition indebtedness (down from $1M of debt principal) and interest on home equity indebtedness is removed entirely. And the entire category of “miscellaneous itemized deductions subject to the 2%-of-AGI floor” under IRC Section 67, which includes everything from tax preparation expenses, unreimbursed employee business expenses, and even the deduction for investment advisory fees (when paid from otherwise taxable accounts).

The significance of these changes is that going forward, it will be even less common for households to have enough itemized deductions to exceed the standard deduction in the first place, thanks to both the much-higher threshold (from consolidating personal exemptions into the standard deduction), and the more limited availability of itemized deductions in the first place (given the cap on state and local taxes paid, and the elimination of the IRC Section 67 miscellaneous itemized deductions). In fact, the Tax Policy Center estimates that barely 10% of households will itemize deductions at all in the future.

From the individual tax planning perspective, this is important because those who claim the standard deduction will find that their previously-itemized deductions are literally “worthless” from a tax planning perspective, and provide no tax benefit. Even if the deduction itself, such as the one for charitable giving, was retained without any changes.

Example 1. Jim is a salesman for a local paper manufacturer, and earns $70,000/year. His deductible expenditures include about 6% in state income taxes (approximately $4,200), plus $2,500/year in property taxes on a small $175,000 house he inherited from his grandmother, and $1,000/year that he donates to his church and other local charities. Under prior law, Jim’s total deductions for income and property taxes alone were $6,700/year, which was enough to surpass the $6,350 threshold for the Standard Deduction, which meant he received the full value of his $1,000 charitable contributions deduction.

In 2018, though, Jim’s Standard Deduction will be $12,000. Which means he will claim the same $12,000 Standard Deduction regardless of whether he makes any charitable contributions or not (because he won’t be claiming itemized deductions at all).

The end result of the above example is that while Jim’s total deductions will increase – reducing his 2018 tax liability – at the margin in 2018, he will no longer receive any tax benefit for his charitable giving! (A phenomenon that is anticipated to hit nearly 21 million households that make charitable contributions in 2018!) Because charitable contributions – and other itemized deduction strategies – are only relevant for those who have enough in total deductions to exceed the Standard Deduction threshold in the first place!

The Rise Of Deduction Lumping

Given the challenge of just having enough in itemized deductions in order to exceed the Standard Deduction in the first place, “deduction lumping” is a strategy of trying to shift the timing of deductions so they are lumped together within the same year, in an effort to clear the Standard Deduction hurdle.

Example 2. Steve is single and makes $80,000 year as a freelance programmer, and owns a $220,000 townhouse with a $180,000 mortgage. His standard deduction (and the hurdle he must exceed to itemize) is $12,000 as an individual taxpayer.

Steve’s state income taxes are $4,000/year (at a 5% state income tax rate), his property taxes are another $2,500 (at a 1.2% property tax rate), and his mortgage interest is approximately $6,750/year (at a 3.75% interest rate). Given that his total itemized deductions are $13,250/year, Steve will be able to itemize, and get an extra $1,250 of deductions over what the Standard Deduction alone would have provided.

However, if instead Steve deliberately underpays his state estimated taxes this year and pays them all next year (on top of the state income taxes he’ll already have to pay for next year) , he’ll still get a $12,000 standard deduction this year, but a total of $4,000 (2018 state income taxes) + $4,000 (2019 state income taxes) + $2,500 (2019 property taxes) + $6,750 (2019 mortgage interest) next year, for a total of $16,750 in deductions (as the SALT cap would limit the income and property taxes to $10,000 instead of their actual total of $10,500). Which means across two years, Steve’s total deductions are $12,000 + $16,750 = $28,750 instead of just $13,250 + $13,250 = $26,500. Which gives him an extra $2,250 in deductions, or about $495 in tax savings at his 22% tax rate.

The improvement comes from the fact that Steve didn’t have to worry about the first $1,250 of his state taxes falling below the Standard Deduction line in 2018, when he lumped all of them into the second (2019) tax year! While he still got the full benefit of the Standard Deduction in 2018 itself.

Notably, in this case, Steve may have an underpayment interest penalty to the state for failing to pay his state estimated taxes in 2018 in a timely manner. However, the Federal government only assesses this penalty at a rate of 2.66% (via Form 2210), and many states have a similar interest penalty. Which on $4,000 of late payments, is “just” a penalty of about $100, which means the deduction lumping strategy still allows Steve to finish ahead.

Unfortunately, the biggest caveat of the deduction lumping strategy is simply that not a lot of deductions can be shifted from one tax year to the next, in order to be lumped together in the first place! For instance, mortgage payments – and their associated interest payments – are generally due when they’re due, without much flexibility to pay the interest any faster or slower (although it is at least possible to control the timing of interest payments, and their deductibility, on a reverse mortgage).

Similarly, it’s not actually feasible to shift the timing of state income tax payments for those who are employees and automatically have state income taxes withheld as a part of the payroll process (as it’s only self-employed individuals and business owners who have the responsibility, and therefore the flexibility, of making their own state estimated tax payments). And under IRS guidance, the timing of property taxes can only be shifted forward to an earlier year if they’re actually assessed in the preceding year (e.g., if 2019 property taxes are assessed in late 2018), although notably if property taxes are assessed late in the year it may be possible to delay them to double up in a subsequent year (e.g., if 2018 property taxes aren’t assessed until late in 2018, waiting to pay them in 2019, in the same year that 2019 property taxes are also paid and can therefore be lumped together). And of course, to the extent that the total of state income and property taxes exceed the $10,000 cap on all State And Local Taxes (SALT), deduction lumping is a moot point, because additional payments above that $10,000 SALT cap aren’t considered, anyway.

And with the elimination of most other miscellaneous itemized deductions (all the ones previously subject to the 2%-of-AGI floor), many deductions with timing flexibility are gone altogether. Although some that remain, such as medical expenses, might have at least some flexibility to impact timing (e.g., paying late-year medical expenses after the new year to lump them into the next tax year).

All of which means that while deduction lumping may be appealing, for many households there simply aren’t many (or any) deductions that are flexible enough to shift and lump together. With the exception of one of the most flexible – and often sizable – deductions of all: charitable contributions.

Charitable Clumping And The Use Of Donor-Advised Funds

The good news of charitable giving strategies, from a tax perspective, is that taxpayers have a lot of control over the timing of the deduction.

Not just because charitable contributions are voluntary – which means you can choose to donate, or not, in whatever years you wish in order to maximize the tax benefits – but also because there’s no cap on the dollar amount of the donation as there is with SALT deductions (beyond the overall charitable contribution limits as a percentage of AGI, though those caps are now as high as a generous 60%-of-AGI for cash contributions to public charities, and 30%-of-AGI for donating appreciated securities to a public charity).

In addition, it’s possible to further control the timing of the charitable contribution deduction by “front-loading” it with vehicles like Charitable Remainder Trusts or a Donor-Advised Fund, which make it even more feasible to clump together a sizable charitable contribution deduction in a single year in order to exceed the Standard Deduction (even if there isn’t a goal or desire for the charity to actually get the money yet).

Example 3. William and Melissa are married, earn $150,000/year in the state of Texas, own a $350,000 single family home with a $275,000 mortgage balance, and give about $3,000/year to local charities. As a result, their deductions include $7,000 of property taxes (at a 2% property tax rate), about $10,000 in mortgage interest (amortizing at a 3.75% interest rate), and $3,000 in charitable contributions. Notably, this total of “just” $20,000 in itemized deductions is not actually enough for them to itemize, given the Standard Deduction for married couples is $24,000 in 2018. Consequently, they receive no tax benefit for their charitable contributions (or any of their other expenditures).

To improve the situation, William and Melissa decide to establish an account with a Donor-Advised Fund, and contribute $15,000 of their S&P 500 index fund (that was bought years ago with a cost basis of only $8,000. This boosts their itemized deductions up to $32,000, allowing them to get $8,000 of additional charitable contribution deductions that are “over the line” (above the Standard Deduction), for a tax savings of $1,920 at their 24% marginal tax rate. In addition, they eliminate a $7,000 capital gain, on which they would have paid another $1,050 in taxes at a 15% capital gains rate.

Over the next 5 years, they will continue to contribute $3,000/year to their charities of choice, but simply make the distributions from their Donor-Advised Fund instead. In the meantime, the cash for the $3,000/year that they would have donated will instead be used to re-purchase the investment in their S&P 500 index fund. Such that by the end of the 5-year time horizon, they will once again have a $15,000 investment back into the fund, but with a new current cost basis from their new purchases (making the old capital gain vanish forever).

The end result of this “charitable clumping” strategy is that by doing 5 years’ worth of charitable contributions at once, the couple gets at least part of the value of the deduction for a charitable contribution, while also saving additional taxes by donating appreciated securities and “replacing” them (at a new, higher cost basis) with the money that would have been donated. Which means the net cash flows into the household and out to the charity are the same… but by engaging in the charitable clumping strategy, the couple obtains both a partial charitable deduction and avoids capital gains. (Or alternatively, the strategy could be executed by simply contributing cash to the donor-advised fund, which doesn’t produce any capital gains tax savings but still results in additional charitable deductions through clumping.)

And of course, the donor-advised fund also can remain invested – which, under the standard rules for donor-advised funds, is all tax-free growth – and if returns are favorable, what was originally 5 years’ worth of charitable contributions could actually last for 6 or 7 years (allowing even more cash flows to be reinvested into a replacement S&P 500 index fund with a new higher cost basis).

The key tax planning benefit, though, is simply that by clumping the charitable contributions together, donations that otherwise would have been itemized deductions falling below the threshold for the Standard Deduction are at least partially above the threshold, producing an immediate tax benefit that simply would not have been received at all if the contributions had been made annually over the years. With the opportunity to use existing appreciated securities – and permanently avoid future capital gains taxes – as an added benefit.

Planning Implications Of Deduction Lumping And Charitable Clumping

Notably, the strategies of deduction lumping and charitable clumping don’t have to be mutually exclusive. In fact, some households may find it more beneficial to engage in both, and further stack their prospective itemized deductions on top of one another. For instance, some deductions might be lumped in alternating years, and charitable contributions might be clumped together 4+ years at a time.

Example 4. Jenny is a freelance consultant making $90,000/year, and lives in a $200,000 condo that she has fully paid off. She pays $6,000/year in income taxes, $2,500 in property taxes, and donates about $2,000/year to various charities.

With total itemized deductions of “just” $10,500, Jenny will end out simply taking the $12,000 standard deduction instead. Consequently, she decides to start lumping and clumping in 2019.

Accordingly, Jenny first and foremost delays paying her fourth quarter estimated taxes of $1,500 until after January 1st of 2019 (as the $10,000 SALT cap limits the value of pushing any more of her state income taxes into 2019).

In addition, in early 2019 she establishes an $8,000 donor-advised fund, to front-lead her next 4 years’ worth of charitable contributions.

The combination of the two makes Jenny’s 2019 deductions $1,500 (2018 state income taxes paid in 2019) + $6,000 (state income taxes in 2019) + $2,500 (property taxes in 2019) + $8,000 (charitable contributions) = $18,000.

In 2020, Jenny won’t have any charitable deductions, and as a result won’t be able to itemize at all (based on just her income and property taxes), but still gets the $12,000 Standard Deduction. In the meantime, the donor-advised fund makes a $2,000 distribution to Jenny’s various charities.

This process repeats itself in 2021 and 2022, but at the end of 2022 Jenny again waits on her 4th quarter estimated taxes for 2022, pushing them into 2023, which produces a greater amount of total itemized deductions when she re-clumps contributions into her donor-advised fund in 2023 as well, for another $18,000 of deductions that year.

The end result is that instead of cumulatively getting $12,000/year in standard deductions (or $60,000 cumulatively over 5 years), Jenny gets a total of $72,000 in deductions instead (thanks to the two years where she had $18,000 of itemized deductions instead of “just” $12,000 for the Standard Deduction). Notably, by just engaging in charitable clumping, Jenny would have only gotten an extra $4,500/year (or $9,000 total) by claiming $6,000/year in income taxes, $2,500 in property taxes, and $8,000 in donor-advised fund contributions; the remaining $1,500 of extra deductions came from adjusting the timing of her 4th quarter estimated taxes to bring her total deductions up to the $10,000 SALT cap in the same years she also clumped together her charitable contributions.

When it comes to proactive planning for deduction planning and charitable clumping strategies, though, it’s crucial to recognize they are only relevant for those who are don’t already have enough itemized deductions to exceed the threshold of the Standard Deduction. And it’s only relevant for those who can reach the threshold by actually pursuing lumping and clumping strategies (as otherwise, it’s a moot point and the Standard Deduction will always apply).

In practice, this means that such strategies will primarily be relevant for high-income single individuals who do not own a property (with a mortgage), and married couples who do own a property. The reason is that high-income single individuals who do not own a property can get close to the $12,000 standard deduction by getting up to the maximum $10,000 SALT cap, and then engaging in charitable clumping on top; those that have a mortgage of any material size will likely already have enough deductions (in the form of mortgage interest) to clear the Standard Deduction, making lumping and clumping a moot point. On the other hand, for married couples, the $10,000 SALT cap – combined with a $24,000 Standard Deduction – would make it almost impossible for deduction lumping alone to produce any tax benefit, and charitable clumping would require a substantial contribution to be relevant… unless the couple has a primary residence with a mortgage, in which case the mortgage interest deductions can bring them close enough where lumping and clumping are relevant again (although a large mortgage can itself produce enough mortgage interest to nearly or fully exceed the Standard Deduction).

Nonetheless, the point remains that for those who do not have enough itemized deductions to reach the standard deduction, but are close enough that they could… the opportunity for deduction lumping (especially for those below the SALT cap) and charitable clumping (especially if there are appreciated investments available to donate) remains appealing as a way to squeeze out a few additional dollars of tax savings. Which repeated systematically over time, can still add up to a material amount of cumulative tax deductions and tax savings!

So what do you think? Will you suggest deduction lumping as a strategy to clear the standard deduction hurdle? What do you think are the biggest opportunities for deduction lumping? How do you plan to communicate these strategies to clients? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!