Executive Summary

Executives and small business owners often struggle to figure out how to diversify a concentrated investment in company stock, due to the adverse tax ramifications of liquidating a highly appreciated investment. Which leads to strategies including variable prepaid forward contractors, exchange funds or stock protection funds to facilitate diversification, or leveraging available tax laws like Net Unrealized Appreciation to mitigate the tax consequences.

But after nearly 9 years of a bull market since the bottom in March 2009, “most” long-term investors now have substantial capital gains. Not because they held a concentrated stock investment that grew, but simply because even a diversified portfolio of mutual funds and/or ETFs may be up 100%, 200%, or even 300% since the bottom. And ironically, the more tax-efficient and “tax-managed” the fund or advisor has been all along, the less turnover there’s been, and the more likely it is to have very substantial embedded capital gains now!

And unfortunately, such large embedded capital gains create real tax complications for engaging in even routine investment adjustments like periodic rebalancing, and especially in situations where the advisor might want to switch strategies (or the investor might want to switch advisors), but “cannot” do so because of the adverse tax consequences.

On the plus side, the reality is that the tax benefits of deferring capital gains are often smaller than most investors realize, as they confuse “tax avoidance” (not recognizing the capital gains) with what really is just tax deferral (the capital gains will ultimately have to be paid if the investor is ever going to use the money).

In addition, relatively straightforward tax strategies can further help investors to get comfortable with unwinding investments with large capital gains, from establishing a “capital gains budget” for the amount of capital gains to be triggered each year (perhaps targeted to stay under the threshold for the next capital gains tax bracket), setting targets for staged sales at progressively higher (or lower) prices to help investors pre-commit to making a change, or simply engaging in a “donate-and-replace” strategy that leverages the tax preferences of contributing appreciated securities for a tax deduction (and eliminating the capital gains altogether) and then replacing the investment (as a new higher cost basis) with the cash that would have been donated in the first place!

The Value (Or Lack Thereof) Of Deferring Capital Gains

First and foremost, it’s important to recognize that “avoiding” capital gains in practice is worth less than most people realize.

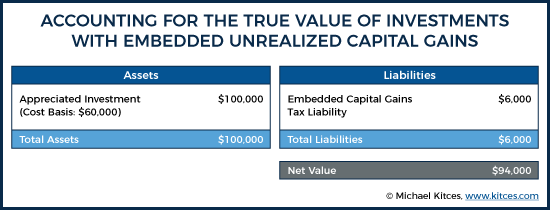

The conventional view is that if an investor has an investment purchased for $60k, that’s now up to $100k with a great bull market, that there’s a 15% long-term capital gain that will “cost” the investor $6,000 in lost taxes. Thus, the longer the investor holds on, the longer he/she can keep the $6,000 (invested)!

But the truth is that unless there’s a plan to die with or donate the asset, the investor will pay $6,000 in taxes. It’s already a tax liability established on the personal balance sheet, albeit a deferred one.

In other words, the investor’s net worth is already actually “just” $94,000. Because the tax obligation is there, even if it hasn’t come due yet!

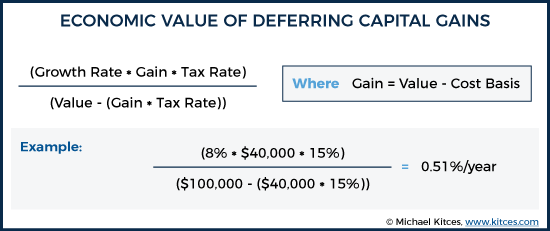

Of course, as long as the investment hasn’t been sold, that $6,000 tax liability isn’t due, which means the entire $100,000 remains invested and “working” for the investor.

Nonetheless, that means avoiding or deferring capital gains doesn’t actually save the investor the $6k in taxes. It just defers the $6,000 of taxes, allowing it to grow in the meantime. Which means the real value of managing capital gains is just the growth on that $6,000 in taxes. Which, at an 8% growth rate, is only $480 of value, or a 0.51% return kicker on the net $94,000 that would have otherwise been available to (re-)invest.

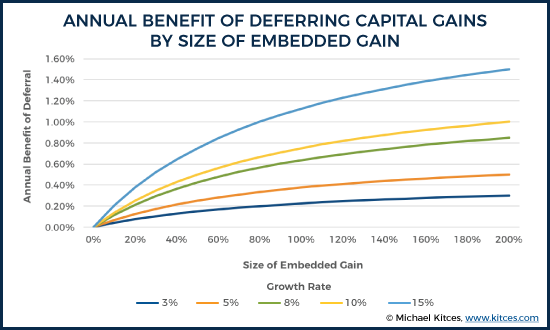

Obviously, an extra 0.51%/year of return certainly is better than nothing. But it’s still rather modest compared to the overall investment risk of a portfolio that can lose 20% or more in a bear market. And this is for an investment that rose from $60,000 to $100,000, which is a 66% gain. For larger gains it is more valuable; on the other hand, for the typical gain that is more moderate (e.g., “just” up 15% or 30%), the (annual) value of tax deferral is even less, as shown in the chart below (for various levels of embedded capital gains and various growth rate assumptions).

As the chart reveals, for investments with a relatively “modest” gain of 20% to 30% - which could still be several years’ worth of growth – the additional annual value of tax deferral amounts to literally not much more than a single day of potential investment volatility! And even with “huge” gains of 100% or more, the annual value of tax deferral is still barely 1%/year, when equities have a 15%+ standard deviation!

The key point: the actual value of waiting to recognize a long-term capital gain, even when it’s a sizable gain, is easily trumped by even a moderate level of additional investment risk by holding the investment if it was otherwise desirable to make a change! (The same is true with respect to the limited value of tax-loss harvesting, as well!)

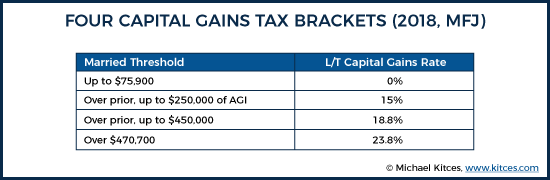

Establishing A Capital Gains Budget To Harvest Capital Gains

One important caveat to the general principle of “deferring capital gains has at least some tax-deferral value” is that it can cause capital gains to cumulatively grow to the point that there’s no way to liquidate without bumping the investor into a higher capital gains tax bracket, which can actually reduce wealth (despite the value of tax deferral). For instance, five years of a $50,000 capital gain at 15% tax rates may result in more wealth than one year with $250,000 of capital gains at the end (some of which will fall into the 18.8% capital gains tax bracket, thanks to the 3.8% Medicare surtax).

As a result, one strategy for managing highly appreciated investments is to set a “capital gains budget” – the maximum amount of capital gains the investor is either willing to absorb and pay the taxes on, and/or the amount of capital gains that can be triggered and absorbed in the current capital gains tax bracket without increasing them above the next threshold (e.g., from the 15% rate into the 3.8% Medicare surtax, or from the combined 18.8% rate into the 23.8% bracket once the underlying capital gains rate lifts up to 20%).

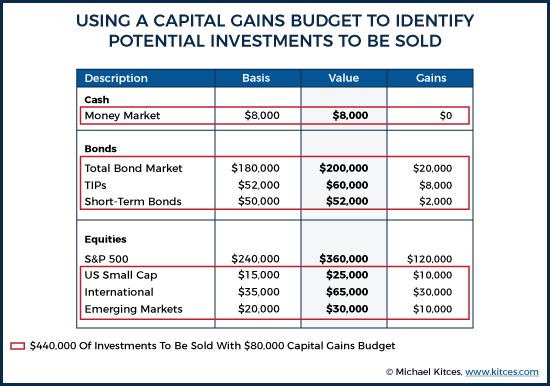

Example 1. Jeff and Susan are a married couple with a combined AGI of $170,000. They are looking to switch to a new advisor with their $800,000 portfolio, but are afraid to make the switch because of the nearly $200,000 of capital gains embedded in the portfolio, due to the market’s recent run-up.

Given that they have another $80,000 of “room” before hitting the $250,000 AGI threshold where the 3.8% Medicare surtax kicks in, the couple sets an $80,000 “capital gains budget” to work with. Accordingly, the advisor can then go through the portfolio and try to identify investments to be sold and transitioned into the new model, that total up to $80,000 of capital gains.

Notably, this will allow the advisor to transition far more than just $80,000 in total value, as a portion of the portfolio may not even have gains, and even highly appreciated investments still have some cost basis as well.

Thus, in the example above, Jeff and Susan’s portfolio might need to hold its larger “core” position in the S&P 500, but the capital gains budget would be sufficient to liquidate and transition everything else. Which means even “just” an $80,000 capital gains budget still made it feasible to transition approximately $440,000 of total assets.

The essence of the capital gains budget strategy is to set a target that is palatable in the first place. Either because it fits within a capital gains harvesting strategy (e.g., to fill a current tax bracket but avoid falling into a higher one), or simply because it’s a total capital gains bill that the client is comfortable with and willing to pay (and lose the small slice of future tax deferral). Harvesting any available capital losses to further offset gains can help, too. (Although ironically, for long-term investors in a strong bull market, there simply may not be any losses left to harvest!)

Of course, for those who are eligible for 0% capital gains rates, the capital gains budget strategy is even more appealing, because the gains are effectively tax-free (at least for Federal tax purposes; state income taxes may still apply!). And some families may be able to further accelerate the process by shifting capital gains via gifting to other family members at their more favorable tax rates. Nonetheless, even those who are subject to higher capital gains tax rates may eventually be able to work through their cumulative gains in 2-3+ years of a capital gains budgeting strategy.

Upside And Downside Targets For Staged Selling

Another approach to working through the need to diversify out of (or simply rebalance) highly appreciated investments is simply to set upside (or downside) targets to sell in stages over time.

This kind of “staged selling” strategy is already popular in the context of concentrated positions in particular, but more basically the idea is that by agreeing in advance to the decision to sell at certain thresholds, and getting a “pre-commitment” from the investor to do so, that it will be easier to sell at those stages when the time actually comes. Because you’re no longer making a real-time investment decision about whether to sell or hold… you’re simply executing a pre-determine plan to sell.

This strategy can be especially helpful for clients who feel like they may be missing out on additional upside by “selling too soon” (as the targets allow for more upside to play out before the sale occurs), or as a means of more disciplined risk management to help them make a transition if the market moves the other way (so the investor doesn’t hold and ride a bear market all the way down). And of course, it’s important to remember that a sale from one investment into another one (particularly of a similar asset class) means the investor will still participate if the overall market continues to rise (albeit minus the haircut of the capital gains tax).

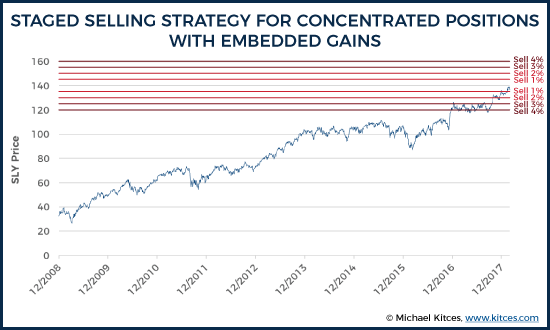

Example 2. In March of 2009, a rebalancing trade after the market crash (re-)allocated 10% of David’s portfolio into small cap stocks. Now, almost 8 years later, his small cap ETF is up nearly 300%, and David is reluctant to sell or even rebalance, even though his small-cap allocation is now up to 14%, which is higher than his originally intended allocation for a conservative growth portfolio.

Accordingly, David’s advisor sets a series of targets for sales. With a current price of 140 for his small-cap ETF, David and his advisor agree that they will sell 1% for every 5 points that the fund moves up or down from here. Thus, if/when it moves to 145 he will sell 1%, at 150 he will sell 2%, etc., up until a maximum target of 160, where he will sell all 4% to return to his originally intended 10% allocation. And the same will apply to the downside, if small-cap stocks have a pullback.

Thus, David doesn’t necessarily have to sell everything (and trigger all the capital gains) immediately, but at least agrees that if/when/as small caps continue to rise, that he can begin to reduce his exposure, while not immediately absorbing the entire shock of the capital gains. At the same time, if small caps (or the overall market) begin to turn around and decline, David has a strategy to diversify out of his overweighting, and take some of his risk off the table.

Of course, a tolerance-band threshold approach to rebalancing can implicitly help to set similar upside and downside sale targets – by agreeing to “automatically” rebalance any time investments are outside of a certain range (such as when a 10% allocation falls below 8% or above 12%). Thus, systematic rebalancing strategies can actually help to prevent embedded gains from ever becoming so sizable in the first place (though not always, especially not if all asset classes rise together!).

For those who didn’t already have rebalancing thresholds in place, though, or otherwise find themselves with an overly concentrated investment allocation with big embedded capital gains, establishing sell targets (to the upside or downside) as a form of pre-commitment device to get buy-in to a future decision to sell (which is usually less painful than just selling today and incurring capital gains immediately).

Notably, though, an important caveat to the strategy is that it still requires clients to actually follow-through and sell when the time comes. And that the market doesn’t move too abruptly – particularly to the downside – such that the investor really doesn’t want to sell after the crash because “now it’s already too late”. One alternative to handle this challenge is to implement a (cashless) collar, by selling a call option at the upside sell targets, and buying a put option to cover the downside risk. Which can trigger the sale simply by virtue of the options following their natural course (to exercise the put option to sell, or have the call option exercised against the investor).

Example 2b. Continuing the prior example, to help ensure that David follows through on the strategy, David’s advisor helps him to sell a call option on the small cap ETF at a strike price of 160, and buys a put option with a strike price of 120, in an amount equal to approximately 4% of the current allocation. Thus, if the price actually does rise above 160, the call option will likely be exercised and the shares will be triggered for sale. While if the price falls below 120, David can (still) exercise the put option to have the sell locked in at the 120 price.

Given that the call option being sold and put option being purchased are both (roughly) equally out of the money, their cost would likely be similar – which means the premium received by selling the call option can cover most/all of the cost of buying the put option, thus ensuring that David will get a price no worse than 120 and no better than 160 (which were the intended sell targets anyway), with little to no net out-of-pocket cost for the guarantee.

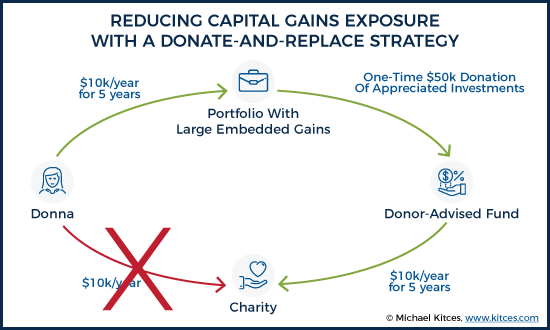

Donate And Replace Strategy With A Donor-Advised Fund

Another way to help investors work through highly appreciated investments is with a “donate and replace” strategy.

The basic idea, as the name implies, is to donate (appreciated) investments to a charity (or more commonly, a donor-advised fund), and then replace the investments by buying them back with “outside” dollars – most commonly, the dollars that would have been used for charitable giving anyway.

Example 3. Donna is very charitable inclined, and typically donates almost $10,000/year to various charities. She also holds a portfolio of investments with substantial capital gains, thanks to the recent years’ bull market run.

To help work through her cumulative capital gains, Donna makes a one-time $50,000 contribution to a donor-advised fund of her most appreciated investment (a small-cap fund that was originally purchased for just $20,000). By making the $50,000 charitable contribution, she receives a $50,000 tax deduction, and her $30,000 embedded capital gain disappears entirely.

Over the next 5 years, Donna then takes the $10,000/year that she would have contributed to charity, and instead adds it back to her portfolio to “replace” the small-cap fund in her portfolio that was donated to the donor-advised fund in the first place.

Notably, to the extent that the donor-advised fund grows – as the funds can remain invested (and even remain managed by the advisor) in a DAF – and can cover 6 or 7 years’ worth of Donna’s charitable giving, she can ultimately replace $60,000 or $70,000 of portfolio investments with new contributions. Each of which will have a new higher cost basis set at the time that Donna makes the investment (rather than with the much-lower cost basis and big capital gain from her original investment years ago!).

The biggest caveat to the donate-and-replace strategy is simply that it only “works” for those who are already charitable inclined and actually making contributions in the first place. As if there isn’t actually a charitable intend to begin with, it’s still better to keep the investment, sell it, and pay the capital gains taxes (keeping 85 cents on the dollar after a 15% capital gains tax rate), than to donate it for “just” a tax deduction but no longer have the money (donating 100 cents on the dollar and recovering only a fraction of it in tax savings). In addition, the strategy is generally only viable for those who are still accumulating and saving and can actually add dollars to the portfolio to replace the contribution in the first place. (Though obviously even retirees can simply donate appreciated investments to fund contributions they were making anyway, even without replacing it, which in some cases is preferable to Qualified Charitable Distributions from IRAs anyway.)

In addition, it’s important to note that the donate-and-replace strategy only produces a charitable benefit for those who contribute enough to exceed the Standard Deduction and actually itemize in the first place (which is important as with a new higher Standard Deduction, it’s harder for many taxpayers to itemize “small” ongoing charitable contributions at all). Though on the other hand, charitable clumping of multiple years’ worth of donations via a donor-advised fund can already be a superior strategy for this exact reason… which is only further enhanced by also whittling down exposure to the investments with the largest embedded capital gains as part of a donate-and-replace strategy as well!

Ultimately, the reality is that for anyone who wants to eventually use their investments (and not die with or donate them), capital gains taxes must be reckoned with. And the actual economic value of deferring “inevitable” taxes is actually far less than most investors realize, as deferral doesn’t actually save on taxes, it merely defers them. Which often adds up to just basis points of value each year at typical growth rates.

Nonetheless, it’s unappealing for most investors to pay taxes any sooner than they feel they have to. Both because tax deferral does have some value, and because the mental challenge – the pain of paying taxes – matters in some cases as much or more than the actual economic consequences.

Accordingly, better educating clients about the true (and more limited) value of tax deferral, combined with strategies like establishing a capital gains budget, setting targets to sell in stages, or a donate-and-replace strategy, can help both ameliorate the actual consequences of capital gains taxes by navigating tax brackets and itemized deductions, and also make it mentally easier to simply sell the investment, and accept the capital gains consequences, in the first place!

So what do you think? How do you talk investors through the decision of whether to make a sale or investment change when there are significant capital gains on the table? What (else) have you found that works? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!