Executive Summary

Regulators around the world require financial advisors to assess their clients’ risk tolerance to determine if an investment is suitable for them before recommending it. For the obvious reason that taking more risk than one can tolerate will potentially lead to untenable losses. And even if the investment bounces back, an investor who loses more money than he/she can tolerate in the near term may sell in a panic at the market bottom, and miss out on that subsequent recovery.

Yet the reality is that many investors end up owning portfolios that are inconsistent with their risk tolerance, and it’s only in bear markets that they seem to “realize” the problem (which unfortunately leads to problem-selling). Which raises the question: why is it that investors don’t mind owning mis-aligned and overly risky portfolios until the moment of market decline?

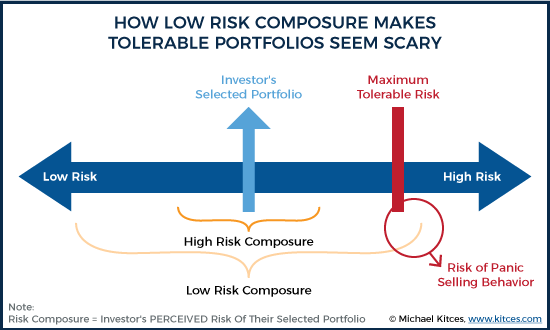

The key is to recognize that investors do not always properly perceive the risks of their own investments. And it’s not until the investor’s perceived risk exceeds his/her risk tolerance that there’s a compulsion to make a (potentially ill-timed) investment change.

Yet the fact that investors may dissociate their perceptions of risk from the portfolio’s actual risk also means there’s a danger than the investor will misperceive the portfolio risk and want to sell (or buy more) even if the portfolio is appropriately aligned to his/her risk tolerance. In other words, it’s not enough to just ensure that the investors have portfolios consistent with their risk tolerance (and risk capacity); it’s also necessary to determine whether they’re properly perceiving the amount of risk they’re taking.

And as any experienced advisor has likely noticed, not all investors are equally good at understanding and properly perceiving the risks they’re taking. Some are quite good at perceiving risk and maintaining their composure through market ups and downs. But others have poor “risk composure”, and are highly prone to misperceiving risks (and thus tend to make frequently-ill-timed portfolio changes!).

Which means in the end, it’s necessary to not only assess a client’s risk tolerance, but also to determine their risk composure. Unfortunately, at this point no tools exist to measure risk composure – beyond recognizing that clients whose risk perceptions vary wildly over time will likely experience challenges staying the course in the future. But perhaps it’s time to broaden our understanding – and assessment – of risk composure, as in the end it’s the investor’s ability to maintain their composure that really determines whether they are able to effectively stay the course!

Risk Perception And Portfolio Changes

It is a requirement of financial advisors around the world to assess a client’s risk tolerance before investing their assets, based on the fundamental recognition that not everyone wants to take the same level of risk with their investments. Which is important, because a mismatch – where the investor takes more risk than he/she is willing to take – creates the danger that the investor will lose more money than they are willing to lose in the event of a bear market. And even if the market recovers, there’s a risk that the investor will sell at the market bottom in a panic along the way.

Of course, if all investors were always astutely aware of their own risk tolerance, and the amount of risk being taken in the portfolio, the need to assess risk tolerance would be a moot point, as investors could simply “self-regulate” their own portfolio and behaviors. The caveat, though, is that not all investors are necessarily cognizant of their own risk tolerance comfort level, and/or face the risk that they will misjudge the amount of risk in their portfolio, and not realize the problem until it is too late.

Thus why the key problem is that investors often sell at the market bottom. Because it’s the moment the investor realizes that they were taking more risk than they were comfortable with, and decides to bail out. Not during the bull market that may have preceded it, because when markets are going up, investors don’t necessarily perceive the risks along the way. In other words, it often takes a bear market (or at least a severe “market correction”) to align perception with reality (as until that moment, ignorance is bliss).

The reason why this matters is that it really means it’s not the mere fact that an investor is allocated “too aggressively” that creates behavioral problems like selling out at the market bottom. Instead, the problem occurs at the moment the investor perceives that reality – e.g., during a bear market decline – and then feels compelled to act. Which is unfortunate, because in practice that’s usually the worst time to do something.

Nonetheless, the key point remains that it’s not actually “investing too risky” that creates the problem for the conservative client. It’s the moment of perceiving and realizing that the portfolio is too risky that actually causes a behavioral response (to sell at a potentially-ill-timed moment).

The Risk Of Misperceiving Risk

The fact that conservative investors don’t sell risky portfolios until they actually perceive the risk they’re taking to be beyond their comfort level is important for two reasons.

The first is that it reveals the key issue isn’t actually gaps between the investor’s portfolio and his/her risk tolerance, per se, but the gap between the perceived risk of the investor’s portfolio and his/her risk tolerance. Again, it’s not merely “investing too aggressively” that’s the problem, but the moment of realizing that you’re invested too aggressively that triggers a behavioral (and often problematic) response.

The second is that it also implies investors could make bad investment decisions even with appropriate portfolios, if they misperceive the risk they’re taking!

For instance, imagine a client who is very, very conservative, and doesn’t like to take much investment risk at all. But it’s 1999, and he’s just seen tech stocks go up, and up, and up. Every year, tech stocks beat cash and bonds like clockwork, to a very large degree. And it’s happened so many months and years in a row, that the client is convinced there’s “no risk” to investing in tech stocks – since as he’s seen, they only ever go up, and never go down!

In this context, if you were a very conservative (bond) investor, and became convinced that tech stocks were going to beat cash every year and it was a “sure bet”, what would you do as a very conservative investor? You’d put all your money in tech stocks!

Of course, once tech stocks finally crash the following year, and it becomes clear they’re not a superior-guaranteed-return-alternative to cash, the conservative investor will likely sell, and potentially for a substantial loss.

But the key point is that the investor didn’t suddenly become more tolerant of risk in 1999, and intolerant a year later when the tech crash began. It’s because the investor misperceived the risk in 1999 (causing him to buy), and then adjusted his perceptions to reality when the bear market showed up in 2000 (causing him to sell). It’s the same pattern that played out with housing in 2006, and tulips in 1636. In other words, it’s not risk tolerance that’s unstable, but risk (mis)perceptions.

Similarly, imagine a client who is extremely tolerant of risk. She’s a successful serial entrepreneur, who has repeatedly taken calculated high risks, and profited from them. Her portfolio is (appropriate to her tolerance) invested 90% in equities.

But suddenly, a major market event occurs, akin to the 2008 financial crisis, and she becomes convinced that the whole financial system is going to collapse.

As a highly risk-tolerant investor, what would the appropriate action be if you were very tolerant of risk, but convinced the market was going to zero in a financial collapse? You’d sell all your stocks. Even as a highly risk tolerant investor.

Not because you aren’t comfortable with the risk of all those stocks. But because even if you’re tolerant of risk, no risk-tolerant investor wants to own an investment they’re convinced is going to zero!

But the key point again is that the investor’s risk tolerance isn’t changing in bull and bear markets. She remains highly tolerant of risk. The problem is that her perceptions are changing… and that it’s her mis-perception that a bear market decline means stocks are going to zero (not just declining before a recovery) that actually causes the “problem behavior”. Because it leads the client to want to sell out of a portfolio that was actually appropriately aligned to her risk tolerance in the first place!

Risk Composure – The Stability Of Risk Perception

Every experienced advisor is aware of a small subset of his/her clients who are especially prone to making rash investment decisions. They’re the ones who send emails asking whether they should be buying more stocks every time the market has a multi-month bull market streak. And they’re the ones who call and want to sell stocks whenever there’s a market pullback and the scary headlines hit CNBC and the newspapers.

In other words, some clients have especially unstable perceptions of risk. The cycles of fear and greed mean that most investors swing back and forth in their views of risk at least to some degree. But while the risk perception of some clients swings like a slow metronome, for others it’s more like a seismograph.

Or viewed another way, it’s those latter clients who seem to be especially prone to the kinds of behavioral biases that cause us to misperceive risk. They are especially impacted by the recency bias, where we tend to extrapolate the near-term past into the indefinite future (i.e., what went up recently will go up forever, and what went down recently is going all the way to zero!). They may also be prone to confirmation bias, which leads us to selectively “see” and focus on information that reaffirms our existing (recency) bias. And for many, there’s also an overconfidence bias that leads us to think we will know what the outcome will be, and therefore want to take action in the portfolio to “control” the result.

In essence, some clients appear to be far more likely to be influenced by various behavioral biases. Others are better at maintaining their “risk composure”, and not having their perceptions constantly fluctuate with the latest news nor becoming flustered by external events and stimuli.

Which is important, because means that it’s the clients with low risk composure who are actually most prone to exhibit problem behaviors… regardless of whether they’re conservative or aggressive investors!

After all, an aggressive client with good risk composure may see a market decline as just a temporary setback likely to recover (given market history), while an aggressive client with bad risk composure may see a market decline and suddenly expect it’s just going to keep declining all the way to zero.

In this case, both are aggressive. For both, the “right” portfolio is an aggressive one, given their risk tolerance (and presuming it aligns with their risk capacity). But the client with bad risk composure will need extra hand-holding to stay the course, because he/she is especially prone to misperceiving risk based on recent events, and thinking the portfolio is no longer appropriate (even if it is).

Similarly, if two clients are very conservative but have different risk composures, the one with high risk composure should be able to easily stay the course with a conservative portfolio and not chase returns, recognizing that even if the market is going up now, it may well experience market declines and volatility later. While the conservative client with bad risk composure is the one most likely to misperceive risk, leading to rapid buying and selling behavior, as he/she becomes convinced that a bull market in stocks must be a “permanent” phenomenon of guaranteed-higher-returns and overinvests in risk… only to come crashing back to reality (and selling) when the market declines.

The key point here is that both conservative and aggressive clients can have challenges staying the course in bull and bear markets. Even if their risk tolerance remains stable. Because some people have more of an ability to maintain their risk composure through market cycles, while others do not. And it’s those low risk composure investors, who are more likely to misperceive risks – to the upside or the downside – that tend to trigger potentially ill-timed buying and selling activity. As they’re the ones most like to perceive that their portfolio is misaligned with what they can comfortably tolerate (due to that tendency to rapidly misperceive risk in either direction!).

Can We Measure Risk Perception And Risk Composure?

From the proactive perspective, the reason that all of this matters is that if we can figure out how to accurately measure risk perception and risk composure, we can identify which investors are most likely to experience challenges in sticking to their investment plan in the future.

Recognizing that it’s not merely about the investor’s risk tolerance and whether he/she is conservative or aggressive with a properly aligned portfolio in the first place… but how likely he/she is to recognize the risks in the portfolio, and that that portfolio is the properly aligned one! And the potential that the investor will misperceive the risk in their portfolio and think they need to buy more or sell out, even if the portfolio is the right one, because the investor has low risk composure and is constantly misperceiving the risk in the portfolio!

Notably, this is also why it’s so crucial to start out by using a psychometrically validated risk tolerance assessment tools in the first place (though unfortunately, few of today’s risk tolerance questionnaires are even suited for the task!).

For instance, imagine two prospective clients come into your office. Both have aggressive portfolios, and say they’re very comfortable with the risk they’re taking. How do you know if the investors are truly risk tolerant, or if they’re actually conservative investors who have misjudged the risk in their portfolios?

The answer: give them both a high-quality risk tolerance questionnaire, and see if their portfolios actually do align with their risk tolerance.

The key here is not to just ask them about what kinds of investment risks they want to take. Because we already know that if they’re misperceiving investment risk, their answers will be biased towards taking more risk, not because they want to, but because they’ve become blind to it!

In this context, the more “pure” the risk tolerance questionnaire (RTQ), and not connected to investment decisions and market trade-offs, the easier it will be to identify who is actually tolerant of risk, and who might simply be misperceiving (and underestimating) investment risks.

Thus, if the RTQ process is completed, and investor A scores very aggressive, and investor B scores very conservative, it becomes clear that investor A is accurately assessing risk and has the appropriate portfolio, while investor B has become risk-blind and needs a different portfolio (and an education on how much risk he/she is actually taking!)

Of course, the caveat is that a gap between a new client’s risk tolerance and their current portfolio provides an indicator of a current misperception, and helps to determine whether the new client should actually have that aggressive portfolio, or not. And the client who so significantly misperceived risk in the first place ostensibly has poor risk composure – after all, if he/she could misperceive risk so much the first time, there’s clearly an elevated risk it may happen again.

But that doesn’t necessarily provide any indicator of who is most likely to be prone to risk misperceptions and have poor risk composure in the future, if they weren’t already exhibiting those problems.

Accordingly, perhaps it’s time for not only a tool to measure risk tolerance, but also one that either measures risk composure, or at least provides an ongoing measure of risk perception. (As a client where the measured risk perception varies wildly over time is by definition one with poor risk composure, and most likely to need hand-holding in future bull and bear markets to keep their portfolio on target.)

For instance, clients might be regularly asked what their expectations are for market returns. The expected return itself (and especially an inappropriately high or low return) is an express sign of risk misperception, and those whose expected returns for stocks and bonds fluctuate wildly over time would be scored as having low risk composure as well.

Alternatively, perhaps there is a way to ask clients more generally questions that assess ongoing risk perceptions, or simply assess risk composure up front. This might include a biodata approach of asking them whether historically they’ve tended to make portfolio adjustments in bull and bear markets (which at least would work for experienced investors), or whether they like to take in current news and information to make portfolio changes, or other similar behavior patterns that suggest they are more actively changing risk perceptions with new information and therefore have low composure.

The bottom line, though, is simply to recognize and understand that in times of market volatility, what’s fluctuating is not risk tolerance itself but risk perception, and moreover that risk tolerance alone may actually be a poor indicator of who will likely need hand-holding in times of market volatility. After all, if it was “just” about risk tolerance, then any investor whose portfolio was in fact aligned with their tolerance should be “fine” in staying the course. But in reality many clients aren’t, not because their portfolio is inappropriate for their tolerance, but because they misperceive the risk they’re taking, causing them to either want to buy more (in a bull market that seems like a sure bet), or sell in a bear market (because who wants to own an investment you believe is going to zero, regardless of your risk tolerance).

Of course, a portfolio that is not aligned to the investor’s risk tolerance will clearly be a problem. But the missing link is that even for those with proper allocations, those with low risk composure will still struggle with their investment decisions and behaviors! And to the extent we can figure out how to identify clients who risk perceptions are misaligned with reality, and who have low risk composure and are prone to such misperceptions, the better we can identify who will actually be most likely to need help (via a financial advisor, or other interventions) to stay the course!

So what do you think? Is the real problem that some investors are risk tolerant and others are not? Or that some investors are better at maintaining their risk composure, while others are more likely to have their risk perceptions swing wildly with the volatility of the markets? Would it be helpful to have a tool that measures not just risk tolerance, but risk composure? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!

You’ve definitely managed to put a name to something that I’ve battled with clients about for years. A client tells me– and their RTQ tells me– that they are rational, level-headed, willing and able to maintain a “Moderately Aggressive” portfolio. Yet within the first year of investment performance results this same client exposes both an inability to understand or perceive the actual risks of his or her portfolio as well as glaringly obvious reasons why they had “bad experiences” during the Dot-com, Housing, and Financial Panic eras. They can’t stop talking about “beating the market” regardless of how many times we have discussed their actual objectives and the rationale for the portfolio, yet at the first sign of volatility– normal volatility of the kind many seem to have forgotten existed prior to the current market’s characteristics– they are thrown into a panic and either pressure me or wonder out loud whether “now is the time to ‘take some profits'”. One thing is clear: they have no grip on their emotions when it comes to their money. Unfortunately, I’ve found many of these people (who lack Risk Composure) to be utterly immune to any attempts to advise or educate them with an eye towards improving their investing outcomes. In a sense, they are doomed to fail (or can only succeed due to luck). It’s sad to see, but it is also nearly impossible to keep these people as clients. In most cases I’ve found that I can only bang my head against the wall they represent for just so long before it becomes clear to me that they are more of a liability than anything else. Some of them might even recognize their emotional, psychological, and behavioral shortcomings/biases when it comes to investing, yet insist on always retaining an adviser to play the role of paid scapegoat. It’s a blame-shifting dance for them and a tremendous waste of time and resources for the adviser. So, at least for those hard cases– those I have tried to rehabilitate time and time again only to wind up back at square one– the only solution is no solution at all… for them, at least: they have to go.

When I started this business, I thought that the RTQ was a

placeholder for compliance reasons … that at best it measured recency bias. But

it was required and expected. Then I thought behavioral surveys might do

better. Financial DNA seemed to do the best job at this. But taking the survey

was a little bit of a chore for clients … it required two different 20 minute

surveys, if I remember right. And then of course the questions about money and

financial experiences. And then Riskalyze, where an investor can see based on

their selection of options how their money would perform over a six month

period. That is our journey … our current tool. It is simple. But the real “Quan”

is something that helps understand behavior like Financial DNA but has the

simplicity of Riskalyze.

Any progress toward that?

I’d be interested to hear about the BD/RIAs adoption of

defending tools like Riskalyze, and FINRA’s policy on these as adequate risk

assessment tools.

Thanks for the article. Took a while to circle around the

point. But it certainly speaks to something I have thought about for the past

12 years.

Mr. Iced Tea,

I am in the same boat as you. Went to Riskalyze (and also use the Rixtrema Fiduciary tool which can model several different market scenarios on the portfolio) and clients love the ease of how this works versus the virtually worthless RTQ’s. Riskalyze lays it out so simply for people in not only showing the percentage gain and loss, but also the dollar amount, which is what hits home with my clients. It is also interesting to show them how the portfolio would do in bull and bear markets and how you can change the assumptions to show them what a spike in interest rates and low stock returns can do as well. I have had a number of clients tell me they are so glad they don’t need to do the RTQ the old way, and that they understand where they stand much better using these new tools. Sure, they are not perfect and are only as good as the “models”, but it is a heck of a lot easier for my clients & me to understand than Finametrica ever was.

The risk composure concept seems to have a lot of merit. I fielded a phone call from an “Aggressive” client that had a recent purchase (about three weeks prior) that was down 3%. His question was if he should make some adjustments (ie. sell) the position.

For anyone who claims to be aggressive, a 3% move should not rattle you to that level.

As a new client of financial planning, I’ve had to understand how risk is being evaluated as my portfolio was being set up. I believe the standard approach – an almost maniacal focus on market volatility and simplistic risk vs. return trade-offs – is very unsophisticated, and unnecessarily tough on clients.

I need my advisor to explain how my portfolio is structured to protect the ability of my portfolio to continue being able to fund my retirement DESPITE market volatility, even in the face of “black swan” events like 2008/9. The key to preserving the ability to fund retirement long-term is to avoid having to sell portfolio equities into down or even decimated markets, thereby sacrificing their future returns we will need (interest rates being sooo low)! If this ability is in place and fully explained to us, then my wife and I won’t have to worry about the “normal” market ups and downs related in these comments! Without this protection AND explanation, people are not going to see the big picture of their plan’s built-in strength in the face of adversity – with all the fear issues mentioned in these posts rearing their ugly heads whenever markets wiggle!

Not mentioned in this piece (but mentioned in prior pieces you’ve written) is the amount of risk the client needs to achieve their goals. And the iterative process good planning utilizes to match the client’s portfolio to their goals, based, in part, on educating the client on how much risk and projected return is contained in a variety of portfolio sets. (And yes, as you’ve also pointed out before, the fraught process of estimating returns is required to do this.) But being able to go back into the software and show the client that they chose a 65/35 portfolio over a 50/50 portfolio because they rated funding their grandchildren’s education as a need rather than a want can go a long way toward managing the client’s behavior.

Reading this today as linked to from a Fina Metrica email. This topic gets even more interesting if we consider the fact that the market gets more and less risky (as valuations rise and fall) and that the average investor perceives the least risk when in fact the market is rising on the risk (valuation) scale and perceives more risk when the market is lower on the risk (valuation) scale!

Kay