Executive Summary

While the CFP certification for financial planning has been around since the early 1970s, it wasn’t until the 1980s and 1990s that it began to gain widespread adoption amongst financial advisors. And it’s only been over the past 20 years or so that the highly scalable AUM model gained enough traction and popularity that the typical advisory firm evolved from solo practices into larger ensemble firms with employee advisors and multiple partners.

As a result, while the essential set of skills needed to establish your own advisory firm are now relatively well known, the most effective path to become a partner in an existing advisory firm is still in its earliest stages, with no set industry norms, a wide variety of career paths from one firm to the next, and a number of firms that haven’t yet designed their formal career tracks at all. Which, to say the least, makes it very difficult for next-generation advisors to figure out where to focus and what to do in order to succeed.

Accordingly, practice management consultant and guru Philip Palaveev has published what should soon become the seminal handbook of next generation advisors pursuing partnership. Because in “G2: Building The Next Generation”, Palaveev – who himself joined a major accounting firm in his early 20s and rapidly ascended to partnership by his early 30s – sets forth exactly what so-called “G2” (second/next generation) advisors in large independent advisory firms should be doing to successfully manage their own career track to partnership, what kinds of expectations are (and are not) realistic, and why (and how) the requisite skills to develop will themselves change as the advisor achieves new levels of success.

Perhaps most notable, though, is the simple fact that at the most senior levels of leadership within an advisory firm, it’s really more about leadership and the ability to manage people, than the actual skill set of being a great advisor. And in turn, the path to leadership and partnership eventually entails growing beyond “just” being a great and expert advisor serving clients, but also learning how to manage and develop a team of subordinates. In addition to learning how to “manage up” to the expectations of founders and senior leadership, with respect to everything from projects and initiatives the advisor might champion, to the advisor’s own career and path to partnership.

Of course, the irony is that when it comes to advisory firms and making partner – like in most industries – success just begets more work and burdens, not to mention a substantial financial commitment to buy in to partnership. Yet at the same time, the good news is that for those who are effective at managing the career marathon, the long-term benefits of becoming a partner – both financial and psychological – can be incredibly rewarding.

G2: The Next Generation Of Financial Advisors

Although the CFP marks originated with the first graduating class of 1973, financial planning didn’t really begin to shift into the consumer mainstream until the 1980s and 1990s. As a result, the majority of today’s most experienced financial advisors – and independent advisory firm owners – were amongst that first and founding generation of financial planners. Now in the advanced stages of their own careers, many have grown their firms to the point that they have hired employee advisors to carry on their client relationships – and the entire advisory business – beyond themselves.

The caveat of this second generation of financial advisors is that the world of financial planning they enter today is fundamentally different than in decades past. While the founding generation of financial planners were virtually all originally insurance or investment salespeople who later evolved their careers and practices to provide financial planning (and become responsible for managing the business they built), today’s “G2” (next generation) advisors are increasingly likely to join existing advisory firms as a support or service advisor, and only later (if ever) grow to the point of being responsible for business development and management, and participating in ownership.

Which means G2 financial advisors have a fundamentally different path to success in their own careers than the founding generation of advisors. Not only because they are more likely to start with financial planning and learn business development later (instead of founders who did it the other way around), but also because founders typically created and ran and grew their own firms, while G2 advisors are responsible for growing their careers within an existing firm, and navigating the dynamics of a growing firm of employees for which ownership – partnership – is often just a distant opportunity to hope for.

In fact, arguably one of the greatest challenges for G2 financial advisors is that because navigating the employee dynamics of a growing multi-partner independent advisory firm is so new, there are few established industry norms and no guide or handbook. At least, not until now.

In fact, arguably one of the greatest challenges for G2 financial advisors is that because navigating the employee dynamics of a growing multi-partner independent advisory firm is so new, there are few established industry norms and no guide or handbook. At least, not until now.

Because advisory firm consultant Philip Palaveev, in his new book G2: Building The Next Generation, has effectively written the Handbook for G2 Financial Advisors (who want to someday become partners), explaining everything that it takes to succeed in an established and growing independent advisory firm, from the necessary stages of personal skills development, to the best way to ensure that your desired career track actually happens in a world where most advisory firms are still figuring out how to create that career track as they go.

The Skills To Develop As A G2 Financial Advisor

One of the most striking aspects of Palaveev’s book for G2 advisors is that it’s a path he’s lived for himself, having joined the national accounting and consulting firm Moss Adams as a young 20-something, made partner by his early 30s, and then ultimately moved into leadership positions at other firms.

Accordingly, Palaveev suggests that the starting point for today’s financial planners trying to navigate their career path in a large firm is to establish some kind of specialization or expertise. Because the reality is that it will be decades before you have enough age and “gray hairs” to command credibility from your experience alone; instead, the best way to overcome the common age bias against you as a younger advisor is to become so expert in a particular topic that – at least as long as you get to talk about that area of expertise – you can command clear credibility, despite your age. Or as Palaveev puts it, “You don’t have to start a relationship by trying to golf with your clients. Start it by being an absolute expert in what matters to them. (Golfing will come to you later!)”

Notably, a key value of establishing a focused area of expertise early in your career within a large advisory firm is not merely to be more credible to the client. It’s that, if you ever want to rise to the position of being a “lead” advisor responsible for client relationships, the client must accept you as an authority. And as long as you are simply a generalist, it’s virtually impossible to be accepted as more of an authority that the founding advisor who originated the client – which effectively limits your ability to move up. Or viewed another way, it will be hard for the client to ever see you as a better generalist advisor than one who is older and more experienced, but if they’re a business owner/executive/retiree and you’re the company’s leading expert for business owners/executives/retirees, you actually can establish yourself as an even better authority on the issues that actually matter to the client.

In the long run, though, success as a financial advisor in a large advisory firm entails more than “just” being an expert able to provide financial planning advice to clients. Those who want to become partners and participate in the ownership of the firm, will generally only have an opportunity to get a slice of the pie if they can help to make the pie bigger. Which means learning to develop new business.

Fortunately, the reality is that establishing a recognized expertise or specialization – which is effectively a form of niching – can help support a younger advisor’s business development efforts. Because while it may take 10-15 years of experience to become established enough in the community to bring in new clients – especially affluent clients – the path to becoming an established expert in your niche is relatively short by comparison. Or as Palaveev puts it, you may not be able to say “I’ve been doing this for 15 years” but you can focus on a niche expertise that allows you to demonstrate you do have something valuable to say (even for clients who are much older).

Ultimately, though, the real path to the most senior levels of the financial advisor career ladder – and making partner – isn’t just about knowledge and expertise, or business development. It’s about management and leadership.

In fact, as Palaveev notes, while the first half of his own career was all about clients and expertise, success in the second half is all about working with others: your team, the (other) partners, and the rest of the firm. At Moss Adams, making partner actually meant spending less time with clients, so that the partner could spend at least 50% of their time on business development, managing the team, and firmwide leadership.

Which is a challenge, because learning to become a good manager – and a good leader – is an entirely different and new skillset than “just” being a good advisor. For many, it’s especially challenging within a larger advisory firm, because co-workers who were formerly friends and peers may suddenly become subordinates to whom the advisor must deliver sometimes candid and critical feedback not as their friend but as their manager and coach. (For which Palaveev recommends Douglas Stone’s Difficult Conversations book to learn how to have difficult conversations effectively.) Though as Palaveev notes, delivering critical feedback – which is essential to avoid undermining the entire team – shouldn’t be viewed as mean or negative (when done appropriately); instead, he suggests it’s a form of respect: “It means that you believe in their professionalism and ability to take feedback constructively and not overreact or ignore it.” Or viewed another way, the most common regret of managers in retrospect is not letting people go, but not letting them go sooner.

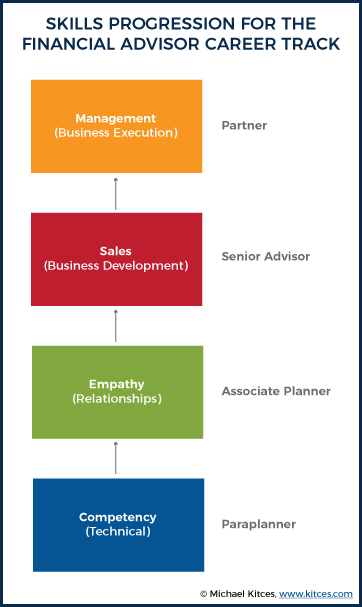

In essence, what all this means is that navigating the career the upward career track in a large advisory firm is about developing an evolving series of skills as the advisor themselves grows from paraplanner (technical competency) to associate planner (relationship management) to a senior/lead advisor (business development), and ultimately towards becoming a partner (management and leadership) in the firm!

Pursuing A Partnership Track Requires Managing Down And Managing Up

In an ideal world, when a new financial advisor joins an existing advisory firm as an employee, there’s a clear roadmap about what it takes to progress up the career ladder and achieve partnership. Yet unfortunately, while this often is the case in large accounting and law firms, the phenomenon of “large” advisory firms is new enough that relatively few have formalized their career track and what it takes to become a partner. In fact, for many firms that are still “small” or even mid-sized (up to $1B of AUM or even more), the firm may have never yet introduced an employee advisor to a partnership opportunity, nor even had the depth of career opportunities to have a “track”… and as a result, the firm is figuring it out as they go, as much as the financial advisor themselves!

Which means in the real world, a key skill that employee financial advisors must learn to reach the pinnacle of their career track is not just the ability to “manage down” – training and developing a team, and various subordinates of the firm – but also in how to “manage up”, which Palaveev defines as “steering information, expectations, and suggested actions to those who are above you on the org chart”.

In other words, it’s not enough to just try to be a “good” advisor and wait and hope for the firm to recognize your contributions to the firm. Especially in a world where the firm owners and founders may not really be certain how to recognize your contributions, or even be in a position to recognize them (as the larger the firm gets, the more distant the founders/partners get from daily interactions with all of the advisory firm’s employees, including new and upwardly mobile advisors!).

Accordingly, Palaveev emphasizes a number of potential tactics for “managing up” in your firm, from the fact that you need to speak up in public forums of the firm and contribute (but it’s important to be recognized as a contributor, and not just someone that constantly argues and plays Devil’s Advocate, which just makes the leadership not want to include you in conversations!), get involved internally with the firm’s committees (an opportunity to show your contributions directly to the leadership that manage those committees), and if you feel “stuck” in your role it’s up to you to broach the conversation with your manager (respectfully) to ask what it is you need to do to grow and move up further. Don’t wait for the firm to manage you into new opportunities; manage up to drive your own career forward by asking what you can do to better grow and succeed!

On the other hand, Palaveev notes that a key aspect of managing up for new opportunities is that they will entail risks, and ones that won’t always work out. In fact, Palaveev defines leadership itself as “The process of making difficult decisions, accepting responsibility for them, and convincing others to follow through.” Which is challenging both because of the outright risks and fear of failure that may ensue, but also because advisory firm owners and founders are often reluctant to give “risky” opportunities to younger advisors – because a failure of the advisor is also a failure with consequences for the firm. Even though the reality is that the only way to really learn effective leadership is to practice making risky decisions that have consequences… and learning from them. For which the starting point is to Manage Up to get those opportunities (and, ideally, to manage expectations about the potential outcome!).

Of course, it’s also important to remember that your own career is much more of a marathon than a sprint. For those who are talented, it’s somewhat “natural” to be impatient with progress – as if you’ve had early success already, you’re probably accustomed to climbing the ladder more rapidly than others around you. Nonetheless, when you look back as a partner who’s been with the firm for 15+ years – or at the tail end of a 40+ year career – you won’t likely remember (or care) whether your big breakout year was your 5th or 7th year in the firm. So even though you may feel that, after 5 (or some other number) of years that “this year must be the year…” it probably doesn’t really need to be. Have patience, and manage up to figure out what it takes to open the next door.

Work/Life Balance And The Risk Of A Partnership Buy-In

Perhaps the greatest irony of doing all the work in pursuing the path to partnership is that being successful virtually always involves… even more work. The good news is that the advisory industry in general, and being a partner in particular, does often provide far more flexibility than traditional employee jobs in most industries. But it’s certainly not easier, and it still takes time and hard work.

Accordingly, Palaveev cautions that G2 financial advisors who pursue a career track should be prepared for the reality that you’ll “feel the squeeze” in trying to balance work, career, family, and children. Especially given that the path to partnership tends to hit in your 30s and early 40s, right around the stress peak of getting married, buying a home, starting a family, and raising young children. For which Palaveev’s only advice is just to accept it. And try to survive as best you can. Or as he puts it, “You won’t always be the most ambitious professional in the office. Or the most dedicated parent at the soccer game. Just never stop trying to be both.” The good news at least is that if you schedule your personal appointments on your calendar, your colleagues will likely respect those commitments (because they’re in the same boat, too).

And of course, if it all goes well, it culminates in an even greater burden of actually buying into a partnership – which will typically involve at least a short-term step back in income (to cover any downpayment and begin making ongoing note payments to finance the purchase), and years of flat income until the loan is paid off, while taking on what may well be the largest debt you’ll ever have in your lifetime (which for larger advisory firms and senior partners, can be substantially larger than even the mortgage on your home). Because the personal career investment of focusing all your time and energy into the firm in the preceding years still wasn’t enough!

Nonetheless, the good news at the end of the journey is that for those who are willing to make the investment, and take the leap of faith, is that climbing to the pinnacle of partnership in a large advisory firm can be very rewarding. According to the latest industry benchmarking data, the typical practicing partner makes $200,000 to $250,000/year in total income, and standout firms have take-home pay per owner of $400,000/year and even higher. Even more substantively, partnership is an opportunity to be a part of a business that impacts hundreds or thousands of clients, the broader community, while creating jobs, opportunities, and careers for dozens or hundreds of employees along the way. Which means that while the first purchase of equity is incredibly difficult – a mixture of fear, anxiety, pride, and excitement – the subsequent purchases are often much easier. In addition, the responsibilities themselves do eventually stabilize, productivity increases, delegating gets easier, and personal efficiency (and work/life balance) do improve.

Again, though, perhaps the greatest real-world challenge in the path to partnership is simply that, unlike more established professions like law and accounting, the track and path to partnership in most advisory firms is not well defined. There are few established industry norms about how to pursue the partnership track, and firm owners themselves may not have a clear vision for the future of the firm (and their role in it). Which means it’s often incumbent on G2 financial advisors to begin the process of Managing Up to craft their own path and future. Both to ensure that they can pursue the opportunity they wish, and because learning to manage – both down and up – is an essential skill to be an effective leader as a successful partner, anyway!

Again, though, perhaps the greatest real-world challenge in the path to partnership is simply that, unlike more established professions like law and accounting, the track and path to partnership in most advisory firms is not well defined. There are few established industry norms about how to pursue the partnership track, and firm owners themselves may not have a clear vision for the future of the firm (and their role in it). Which means it’s often incumbent on G2 financial advisors to begin the process of Managing Up to craft their own path and future. Both to ensure that they can pursue the opportunity they wish, and because learning to manage – both down and up – is an essential skill to be an effective leader as a successful partner, anyway!

And for those who still aren’t certain how to proceed, and/or want additional practical advice, I can’t more highly recommend Philip Palaveev’s book G2: Building The Next Generation. Or as I call it: the handbook for the next generation of financial advisors.

So what do you think? What skills are needed to develop as a G2 financial advisor? Does pursuing a partnership track require the ability to both manage down and manage up? Does pursuing partnership inherently mean sacrificing some work/life balance? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!

Leave a Reply