Executive Summary

A reverse mortgage allows homeowners to borrow against their primary residence, without making any ongoing payments; instead, interest simply accrues on top of the principal, and most commonly is not repaid until the homeowner either moves and sells the home, or when it is sold by heirs after the original owner passes away.

The caveat, however, is that if reverse mortgage interest accrues annually instead of being paid, it cannot be deducted each year under the “normal” rules for deducting mortgage interest. And a similar caveat applies to mortgage insurance premiums, which might be deducted (at least, if Congress reinstates and extends the rules that lapsed at the end of 2017), but only if they’re actually paid – which, again, typically isn’t the case with a no-payment reverse mortgage.

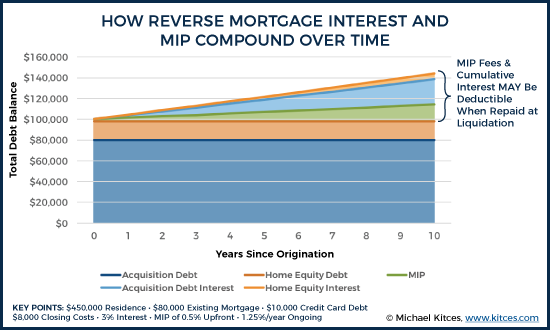

Of course, the reality is that when the loan is ultimately repaid in full – even if all at once – the accrued mortgage interest and mortgage insurance premiums do become deductible at that time when actually paid. The problem, though, is that if compounded for enough years, the size of the deduction may be too large to use… or at least, the liquidating homeowner (or heir) may need to plan to create income in the year the reverse mortgage is paid off, just to ensure there’s enough income to be offset by the deductions.

Furthermore, reverse mortgages can also complicate the tax deductibility of real estate taxes. To the extent real estate taxes are paid directly – even as a cash payment with proceeds from a reverse mortgage – they remain deductible. However, with the HECM reverse mortgage’s new Life Expectancy Set Aside (LESA) rules, it’s not entirely clear whether real estate taxes paid directly from the set aside are fully deductible in the same manner, or whether they might have to be accrued and claimed at liquidation, similar to the reverse mortgage interest deduction and mortgage insurance premium deduction!

Taxability Of HECM Reverse Mortgage Loans And “Income”

One of the most popular selling points of a HECM reverse mortgage is that the money received is “tax-free”.

In reality, cash paid out from a reverse mortgage, whether as a lump sum or ongoing “income” payments, is tax-free simply because it’s ultimately nothing more than a loan against an existing asset. In other words, no income or wealth is created in the first place; the borrower is simply taking out a personal loan and using his/her primary residence as the collateral, which isn’t any more taxable than getting a loan to buy a car or pay for college, or taking out a home equity line of credit or borrowing against a life insurance policy.

The fact that the borrower may use periodic cash flows received from the loan as an “income” substitute to pay his/her bills, fortunately, doesn’t cause the loan to become taxable. It’s still a loan, and as a result, the cash payments remain a non-taxable receipt of loan proceeds against an existing asset, just like other types of (secured or unsecured) loans. Regardless of whether the reverse mortgage is an upfront lump sum, a line of credit that’s drawn against periodically, or tenure payments for life.

Notably, the fact that a reverse mortgage loan isn’t income for tax purposes, also means it doesn’t impact other tax-related issues for retirees, like the taxability of Social Security payments or income-related premium surcharges for Medicare Parts B and D. Because, again, while it might be colloquially called “income” for household cash flow purposes, in practice it’s simply a loan (subject to certain reverse mortgage terms and borrowing requirements).

Deductibility Of HECM Reverse Mortgage Interest

While the tax treatment of the proceeds from a HECM reverse mortgage loan is rather straightforward (it's nontaxable), there is far more tax complexity when it comes to the deductibility of reverse mortgage interest. This is due both to the limitations of the general rules for deducting mortgage interest in the context of how reverse mortgages are typically used, and also because of the way that reverse mortgage interest is usually paid (not on an ongoing basis as occurs with traditional mortgages).

Standard Tax Rules For Deducting Mortgage Interest

The standard rules under IRC Section 163(h) is that “personal” interest is not tax deductible. But there is an exception under IRC Section 163(h)(3) that allows a deduction for payments of “qualified residence interest” – i.e., mortgage interest that is classified as either “acquisition indebtedness” or “home equity indebtedness”.

Acquisition indebtedness is a mortgage debt incurred to acquire, build, or substantially improve either a primary residence or a designed second home. Home equity indebtedness is any type of primary residence or second home mortgage debt that doesn’t qualify as acquisition indebtedness.

The classifications of mortgage debt are important because of the limitations. Interest on the first $1,000,000 of acquisition debt principal is deductible, but taxpayers can only deduct the interest on the first $100,000 of home equity indebtedness. In addition, interest on home equity indebtedness is an AMT adjustment (which means the deduction is lost entirely for those already paying AMT).

Notably, the rules classifying mortgage debt are based not on what the mortgage is called by the lender, but how the loan proceeds are actually used. Thus, a home equity line of credit to build an expansion on the home is “acquisition debt”, but a cash-out refinance of a 30-year mortgage used to consolidate and repay credit card debt is home equity indebtedness (at least for the additional cash-out portion of the loan). And a mortgage against a primary residence taken out when it’s purchased is acquisition debt (as the loan was used to buy the property), but if the owner buys the property with cash and later does a cash-out refinance for the exact same mortgage amount and terms will have the interest treated as home equity indebtedness (because the loan proceeds weren’t used to acquire the residence, since it had already been acquired at that point).

It’s also important to note that mortgage interest deductibility is further limited to a debt balance that does not exceed the original purchase price of the home (adjusted for reinvestments for home improvements) under Treasury Regulation 1.163-10T(c)(1). Thus, for instance, if the original purchase price was $300,000 and a home expansion increased the adjusted purchase price to $350,000, the owner can never deduct mortgage interest on more than $350,000 of mortgage debt. In most typical traditional mortgage situations, this is a non-issue, as the mortgage would typically start at $300,000 or less, and amortize down over time. However, the issue can arise if the house appreciates in value and a subsequent cash-out refinance increases the mortgage balance above the original purchase price (plus improvements). And it can also be a limiting factor for negative amortization loans (where the interest compounds against the loan balance over time), which as discussed below, includes reverse mortgages.

In addition to the rules to deduct primary residence mortgage interest, there are also rules to deduct interest for investment real estate or to claim interest as a deduction against rental real estate, but those rules are a moot point for a reverse mortgage since a reverse mortgage must be against your primary residence.

Deducting Reverse Mortgage Interest Payments

In the case of a reverse mortgage, it is still indebtedness against a primary residence, which means the same rules apply to deduct reverse mortgage interest, including the determination of whether the loan balance will be classified as acquisition debt or home equity indebtedness depends on how the money is used. Thus, if the borrower takes out an upfront lump-sum reverse mortgage to refinance other debt, it’s home equity indebtedness; if the reverse mortgage is used to buy a new retirement home, or to make home modifications on your existing home for your retirement, it can be acquisition debt.

Fortunately, a new mortgage that is simply refinancing of existing acquisition debt continues to count as acquisition debt as well, which means a reverse mortgage used to refinance a traditional mortgage can also be acquisition debt (if the original mortgage was in the first place). Though notably, even if the reverse mortgage is acquisition debt and its interest is deductible as such, technically the interest on the interest that may accrue in a negatively amortizing reverse mortgage should be treated as home equity indebtedness (although the calculation of it would be complex, and it would be difficult for the IRS to track as well since there is no automatic reporting process to the IRS about the type of mortgage debt).

However, the important caveat to the reverse mortgage interest deduction is that under IRC Section 163(h), the interest is only deductible when it is actually paid. Which is a big deal for a reverse mortgage, because the borrower is typically not making interest (or any payments) on an ongoing basis! He/she may choose to make ongoing payments - which are applied to the aggregated accumulated Mortgage Insurance Premiums, then cumulative servicing fees that have accrued, and then finally accrued interest that may be deductible (per the Model Loan terms for a HECM reverse mortgage). But most commonly, interest (and the other expenses) simply accrues on top of the reverse mortgage principal over time (since the whole point of the reverse mortgage is often to relieve the cash flow obligation of making ongoing payments). Yet if the reverse mortgage just accrues and compounds, there is no mortgage interest deduction on a year-by-year basis, because it’s not actually being paid.

Instead, the cumulative loan interest is often repaid when the reverse mortgage finally “terminates” – either because the borrower ceased to use his/her the property as his/her primary residence, decided to repay the loan, or in many cases because he/she passed away and the property is being liquidated by the estate or heirs in order to repay the loan.

Recovering A Lost Deduction For Reverse Mortgage Interest?

The problem with the typical lump sum repayment of a reverse mortgage is that when the cumulative loan interest is all repaid all at once – and thus would be claimed as a deduction all at once when paid – then there is a realistic risk that the accrued debt could exceed the adjusted purchase price (which limits the deductibility). Furthermore, there’s a risk that a large portion of the mortgage interest deduction could be lost entirely, because the taxpayer may not have enough income to be offset by the deduction!

In their Journal of Taxation article “Recovering A Lost Deduction”, Sacks et al. explore the dynamics of how to avoid losing (or recover) the tax benefits of the reverse mortgage interest deduction, when loan interest is accrued and repayment in a single year could cause negative taxable income (where deductions exceed income, and the excess deductions are unable to be used and cannot be carried forward).

The most straightforward way to resolve this issue is simply to plan that, in the tax year the reverse mortgage is (going to be) repaid, the owner will create taxable income if necessary, to ensure that there is income that can then be absorbed by the mortgage interest deduction. This might be accomplished with an IRA distribution, a partial Roth conversion, or simply by ensuring that the owner’s total income from other sources is sufficient to fully offset the available deduction. If the primary residence had appreciated enough – such that there’s a capital gain even after the up-to-$500,000 capital gain exclusion for the sale of a primary residence – the excess capital gains are also “income” that can be offset by the mortgage interest deduction (and while the deduction is less valuable when applied against a capital gain instead of ordinary income, it’s still better than being lost altogether because there isn’t enough income at all!).

In many cases, though, the situation is further complicated by the fact that in reverse mortgage payoff scenarios, there’s often a question of who gets to claim the interest, since the reverse mortgage may be repaid because/after the original homeowner dies. Which means it’s a tax issue for the estate or the heirs, not the original borrower/homeowner!

Fortunately, Treasury Regulation 1.691(b)-1 does allow a decedent’s prospective deductible items that hadn’t been paid at death to be deducted subsequently when paid by beneficiaries. However, in many cases, the beneficiaries don’t have enough income either, especially when the estate inherits the house to liquidate but doesn’t inherit pre-tax retirement accounts that might have created taxable income (as the retirement accounts typically go directly to beneficiaries by beneficiary designation).

Accordingly, consideration should be given to who will inherit a property subject to a reverse mortgage that might be repaid after death, and whether he/she will have sufficient income to offset/absorb the available deduction. This might mean ensuring the house passes directly to heirs that receive other assets (e.g., with a Transfer on Death rule) rather than just bequesting it under the will, or at least give the executor the flexibility to distribute the residence and mortgage in-kind for beneficiaries to subsequently liquidate (to claim the deduction on their own tax returns, where they have more assets that might create income that can be offset by the deduction, including recently inherited IRAs!).

Alternatively, the borrower can avoid the potential clustering of the reverse mortgage’s interest deduction payment at death by voluntarily paying the interest annually along the way. However, this would require truly paying the interest – not merely having it accrue against the reverse mortgage, or paying it and then immediately repaying yourself from the reverse mortgage – and may or may not be manageable for the retiree’s cash flow (especially since payments aren't applied against interest until the accrued MIP and servicing fees are repaid, first!).

In addition, it’s notable that paying the mortgage interest on an ongoing basis is only deductible if the borrower actually itemizes deductions in the first place, which isn’t always the case for retirees, especially in the future if the standard deduction is increased in 2017 and beyond under the President Trump or House GOP tax reform proposals. If the standard deduction ends up being higher and itemized deductions are indirectly curtailed for many retirees, it might actually become more desirable to simply allow the mortgage interest to accrue and be “bunched together” to repay at the end – though, again, it’s still necessary to ensure there’s at least enough income in that liquidation/repayment year to actually absorb the full deduction at that time.

Deducting The Mortgage Insurance Premium Of A HECM Reverse Mortgage

In addition to the potential deduction for a reverse mortgage’s mortgage interest payments, taxpayers can also potentially deduct mortgage insurance premiums as mortgage (“qualified personal residence”) interest, under IRC Section 163(h)(3)(E). However, to claim the MIP deduction, it’s necessary that the mortgage itself have been issued since January 1st of 2007, and that the reverse mortgage debt itself be classified as acquisition indebtedness and not home equity indebtedness. As a result, the deductibility of the MIP will be contingent on how the proceeds of the reverse mortgage are actually being used (to determine whether it qualifies as acquisition indebtedness in the first place).

The deductibility of a mortgage insurance premium (MIP) is highly relevant for reverse mortgages, given that they have both an upfront MIP of 0.50% to 2.50% and an ongoing MIP of 1.25%.

Again, though, payments – whether for mortgage interest or mortgage insurance premiums – are only deductible when actually paid, which means that when the upfront MIP is rolled into the reverse mortgage balance and the annual MIP is accrued on top of the mortgage balance, the payments haven’t been made, and thus, the MIP cost can’t be deducted. Instead, as with mortgage interest, if the payments aren’t actually made until the property is liquidated and the reverse mortgage is paid off in full, then the MIP will solely be deductible at that time, all at once, and face the same issue regarding whether there’s enough income available to absorb the deduction. If ongoing payments to the reverse mortgage are made, the MIP may be deductible (if otherwise eligible), and notably repayments to a reverse mortgage are presumed to be allocated towards the (accrued upfront and ongoing) MIP first.

In the case of the MIP deduction, the situation is further complicated by the fact that the MIP deduction begins to phase out above $100,000 of AGI (for both individuals and married couples filing jointly), and fully phases out once AGI reaches $109,001. Thus, if the MIP deduction comes due all at once, it may create income against which the deduction will be offset can also push the taxpayer over the line where none of the MIP is deductible anyway.

In practice, though, these constraints may prove to be a moot point, as technically the deduction for mortgage insurance premiums was last extended under the PATH Act of 2015 through the end of 2016, and lapsed as of December 31 of 2016. Of course, it may ultimately be reinstated later in 2017 – and in point of fact, it has been retroactively reinstated after lapsing more than once in the past decade already. Or it could become a matter of permanent tax law under looming 2017 income tax reform. Nonetheless, as it stands now, MIP payments aren’t even deductible in 2017, much less in a distant future year when the property is finally sold and the reverse mortgage is liquidated in full.

Notably, even if the deduction for mortgage insurance premiums does get reinstated and stick around, the relative balances of mortgage insurance premiums, interest, and principal, are not directly tracked in the current Form 1098 reporting from the lender. Which means at best, the balances would have to be determined (or reconstructed retrospectively) from monthly reverse mortgage statements just to figure out how much of the MIP might be deductible.

How Reverse Mortgages Impact Real Estate Tax Deductions

One final point of tax complexity with a reverse mortgage is how to handle the tax treatment of real estate taxes that are paid via a reverse mortgage.

In general, the deductibility of paying real estate taxes follows the “normal” rules under IRC Section 164 – the taxes are deductible when actually paid. Thus, regular payments for real estate taxes through a mortgage servicer’s (as part of the full PITI monthly payment) are still deductible because they were actually paid (even if through the servicer’s escrow arrangement), and a direct payment of real estate taxes (e.g., to the county because the mortgage has already been paid off) are also deductible when paid.

For those who use a reverse mortgage to generate the cash to make the payment for real estate taxes – whether by drawing against the home equity line of credit, using the lump sum proceeds of a cash-out reverse mortgage, or paid via the ongoing tenure payments structure – the favorable tax treatment of real estate taxes is the same. From the tax code’s perspective, the fact that the taxpayer got the money to make the payment from a (reverse mortgage) loan is irrelevant; all that matters is that an actual payment was made, to satisfy the legal tax obligation.

The situation is somewhat more ambiguous in the case of real estate taxes that are paid directly from the HECM reverse mortgage, which can happen for taxpayers that fail to meet underwriting requirements and have a “Life Expectancy Set Aside” (LESA). The LESA rules are intended to ensure that reverse mortgage borrowers don’t unwittingly default on the reverse mortgage by failing to make property tax (and homeowner’s insurance) payments, by instead drawing those amounts directly from the reverse mortgage, holding them in escrow, and them remitting the payments for taxes and insurance as appropriate. In essence, the LESA rules ensure that the borrower doesn’t max out the reverse mortgage borrowing limit for other purposes, and then runs out money to pay taxes and insurance; instead, the reverse mortgage is carved out to pay the taxes and insurance, and the homeowner is left to be responsible for the rest of his/her bills (but without property taxes and homeowner’s insurance looming).

In the LESA scenario, the taxpayer doesn’t directly make a personal cash/check payment for property taxes, because the payment is drawn against the reverse mortgage balance and remitted directly to the county. Nonetheless, some argue that given that the legal tax obligation is satisfied and the taxpayer incurs an actual debt (an increase in the reverse mortgage balance) in the process, it should still be constructively treated as a “payment” for tax purposes at the time the property taxes are paid via the reverse mortgage, even if it wasn’t a personal cash outflow for the homeowner. Still, though, there is no definitive tax guidance to clarify the treatment, and more clearly distinguish why an increase in reverse mortgage debt balance for interest is not a deductible “payment” while a similar increase in the debt balance for a payment of real estate taxes is a deductible “payment”.

So what do you think? Have you had clients concerned about the tax rules for reverse mortgages? Will HECMs become more popular and increase the importance of reverse mortgage tax planning? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!