Executive Summary

The traditional approach to saving for retirement is all about starting early, saving consistently, and letting compounding growth do most of the heavy lifting over time.

Yet the reality is that for those who are still early in their careers, there really may not be enough income coming in to save in the first place. It’s only as income rises that savings behaviors really start to matter. And for those who have saved long enough, eventually the impact of savings is muted by the sheer size of the portfolio, as compounding growth becomes the driving factor in reaching retirement success. Until the retirement date actually looms close, and then preserving the portfolio for the retirement transition is more important than just trying to maximize growth.

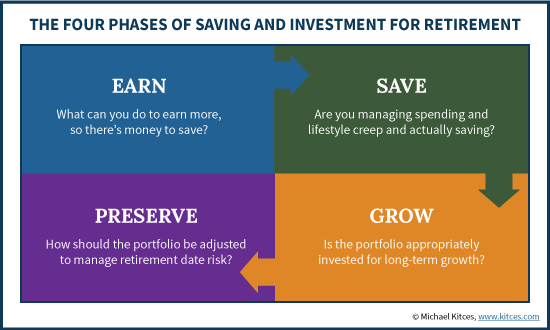

In fact, this framework of Earn, Save, Grow, and Preserve can be a helpful way to think about the progression of accumulating for retirement. Each phase has its own unique issues to be navigated, and success in one phase leads to the challenges of the next.

Most importantly, though, considering the four phases of saving and investing for retirement is crucial to ensuring that the retirement advice being delivered is relevant in the first place. After all, focusing on strategies to maximize portfolio growth are irrelevant for those who can’t afford to save yet, and for those with a large retirement portfolio, ongoing contributions become irrelevant and the focus must be on growing and preserving the nest egg instead!

Conventional View Of Saving And Investing For Retirement

The conventional view of saving and investing for retirement holds a consistent series of core tenets:

- Spend less than you make

- Automate your savings strategy (“pay yourself first”)

- Maintain a healthy exposure to equities for long-term growth

- Maintain a diversified portfolio to manage your risk

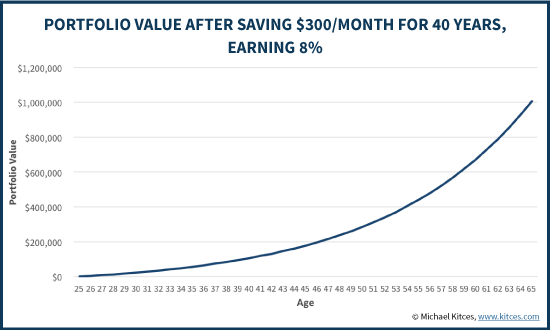

In turn, this leads to a relatively straightforward retirement savings strategies of “start early, save consistently, and let compounding growth work for you over time.” After all, it takes just $300/month of savings from age 25 to 65 to accumulate a $1,000,000 nest egg (assuming an 8% growth rate over time).

The 4 Phases Of Saving And Investing For Retirement

The caveat to the traditional view on accumulating for retirement is that in reality, an individual’s income, spending, and ability to save vary greatly throughout life. From the impact of raises and promotions (especially significant in the early years of a career), to starting a family (and then moving on to the empty nest phase later), steady saving for retirement is not necessarily as feasible as the conventional view would suggest.

Similarly, the reality is that the importance of investment returns and risk management vary over time as well. Those still in the early years of accumulation have such a long time horizon, they still have the capacity to take significant risk in the portfolio, while in the later years an adverse market event could drastically derail a retirement plan and the planned retirement date. And the simple truth is that in the early years, the actual dollar amount of growth is so small, it’s often dwarfed by ongoing contributions; it’s only in the later years that growth becomes the real engine driving the portfolio to the retirement finish line.

In other words, accumulators progressing towards retirement will actually go through phases that have distinct challenges. After all, focusing on whether you Save isn’t relevant until you’re Earning enough to save. And success in the Saving behavior itself eventually creates a portfolio large enough that the Growth is what matters the most. And years of compounding Growth is what closes the gap on retirement, bringing the retirement date closer but also accentuating the need to Preserve the portfolio and manage the retirement date risk.

Thus, over time an accumulator will need to navigate each of these four distinct phases in turn: Earn, Save, Grow, and Preserve.

Earn: CAN YOU Save For Retirement?

In the first stage of saving for retirement, the driving issue is simply whether you earn enough that you can afford to save or not. In other words, does your income exceed your expenses, such that there is something left over to save in the first place?

Of course, the reality is that at virtually any income level, there will be a group of people who spend more than they make, and can’t seem to find any available dollars to save. But for prospective savers in their early working years, who may still only be earning minimum wage, they really may not be earning enough yet to have any material dollars left over to save, after covering just the basic household essentials (food, shelter, and clothing). Or perhaps they are earning slightly more than minimum wage, but are burdened by student loan or other debt payments that leave little cash flow available for saving.

For people facing this situation, the ‘traditional’ advice to spend less and save more isn’t very effective, because there really isn’t much of any spending to cut in order to spend less. Instead, the real path to financial success from here is not to spend less and save more, but to earn more to save more.

In other words, the key issue for those in Earn stage of saving for retirement is to figure out how to increase their income earnings so they can save in the first place. That could be figuring out a side hustle for some extra income, or reinvesting any available dollars (if there are any!?) into a course or training to improve the career trajectory, or even just coaching on how to ask for a raise.

But again, the fundamental point is that early on, the best advice to save more for retirement is to earn more so you can save in the first place!

Save: ARE YOU Saving For Retirement?

As income begins to rise during the early working career, suddenly a prospective saver may reach the point where there’s enough income to cover the bills (and outstanding debts) with something left over. So what do you do with the extra income? At this stage, it’s no longer a question of the sheer capacity to save, but instead about taking action to save, or whether that extra income is spent instead.

Certainly, one of the great ‘joys’ of generating additional income is the opportunity to spend it on the pleasures of life, but allowing the lifestyle to creep higher every time there’s a raise means no saving will ever actually get done. At some point, it’s necessary to actually commit that not all of the next raise will be consumed, and instead that some of it will be saved, instead.

Of course, the temptation to spend more is everpresent, and lifestyle creep is called that precisely because it tends to “creep up” slowly and steadily without realizing it… until the realization comes that income has significantly risen and there’s still no money left over to save at the end of the month!

Accordingly, success in this stage of retirement savings is all about managing spending and saving behavior to actually facilitate saving. Whether it’s automating savings behaviors, or finding other ways to “pay yourself first”, or committing to “Save More Tomorrow”, or trying to actually cut spending to free up more money to save, the outcomes will be driven not by the financial capacity to save, but the behavioral ability to reign in lifestyle choices and direct free cash flow to savings instead.

Grow: How Much Is Your Retirement Nest Egg GROWING?

As savings behaviors are cemented into place, and fuel a rising balance for the retirement nest egg, eventually the portfolio becomes so large that each incremental contribution no longer has a significant impact.

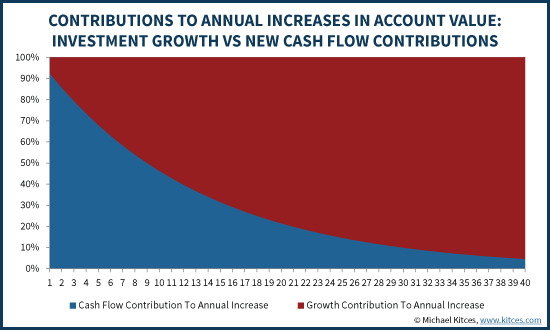

For instance, saving $300/month allows an account balance to grow to $3,600 by the end of the first year. In the second year, the account may grow slightly, but the increase in the account balance will again be driven primarily by the contributions (as a year’s worth of growth may still be less than a single month’s worth of contributions). After 10 years of the same behavior, though, suddenly only half of the annual increase in the account balance is driven by new contributions, while the remainder is driven by growth on the existing balance. After 20 years, growth will drive 75% of the annual increases in the account balance. After 30 years, it’s almost 90%.

This shifting dynamic means that after a decade or two of ongoing contributions, the greatest driver of the outcome isn’t the spending behavior and ongoing contributions anymore; now it’s the ability to grow the portfolio, and the returns being generated.

In turn, this means that as the portfolio grows, paying attention to how it’s invested begins to matter, a lot. In the early years, improving returns by 1%/year still has a trivial impact compared to saving another $100/month. In the later years, adding 1%/year to returns is highly material.

Accordingly, in the Grow phase, it becomes necessary to really look at the portfolio itself. Is it properly invested for growth? Is there a reasonable asset allocation? If investment/fund managers are being used, are they really providing value for their cost? And are the portfolio costs being managed overall, given the dramatic impact they have on long-term returns?

The bottom line: in the Grow phase, paying attention to the finer point details of how the portfolio is invested can really begin to pay off (for the first time).

Preserve: Are You MANAGING THE RISK As Retirement Approaches?

As the planned date of retirement draws near, the dynamics shift once again, as the shortening time horizon becomes highly relevant. Suddenly, as the portfolio reaches its largest value, contributions are dwarfed by the portfolio volatility, and the risk of a severe bear market in the final years (and the time it would take to recover) can substantially derail the planned retirement date. In other words, Preserving the portfolio and managing the risk becomes the dominating factor for success.

Of course, the reality is that retirement itself can entail a multi-decade time horizon, so it’s not feasible to eliminate all portfolio risk. Nonetheless, as the retirement date approaches, preserving the portfolio and managing “retirement date risk” is increasingly relevant, as if a market decline occurs, savings alone can no longer make up the difference.

In point of fact, target date funds already engage in this strategy, with an “equity glidepath” that decreases in the final years to preserve the portfolio as retirement approaches. And many variable annuities with “living benefit” riders (e.g., GMWB or GMIB riders) are used for a similar purpose in the final accumulation years. In theory, even a simple strategy of buying out-of-the-money puts to preserve the portfolio by hedging the magnitude of any downside risk in the final years could be effective (akin to how many structured notes are put together).

Nonetheless, by whatever means, the key issue for a prospective retiree in the final years leading up to retirement is less about generating growth, or making ongoing contributions, and is more about sustaining moderate growth while also Preserving the portfolio to manage the looming retirement date risk exposure.

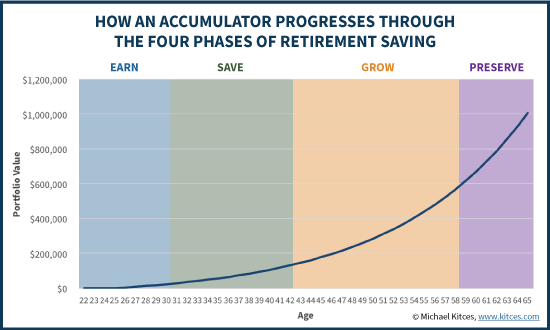

Progressing Through The Four Phases Of Retirement Accumulation

A successful accumulator who is “on track” for retirement from their early 20s through their mid 60s might spend most of their 20s just trying to improve their earnings enough to save, would focus on sustaining their savings (and avoiding lifestyle creep) in their 30s and early 40s, allow compounding growth to work for them through the rest of their 40s and 50s, and start considering the risk management issues as they approach their 60s and the retirement transition looms. In other words, the Earn, Save, Grow, and Preserve phases will come sequentially over time, as success in each leads to the next.

Of course, for an accumulator who is not on track for retirement, their progression through the phases may not align with the ages noted above. Nonetheless, from the perspective of achieving retirement success, the fundamental point is that the “right” advice for an accumulator depends on which phase they’re in. Giving advice focused on the later stages of growth and preservation is largely irrelevant to someone still in the Earn or Save phases, just as focusing on earning more or saving more is not very relevant for someone in the preserve stage leading up to the retirement transition (where the portfolio is so large that incremental earnings and savings won’t have much impact anyway).

Ultimately, though, the point is simply that effective advice for retirement accumulators will vary over time. In the Earn phase, it’s all about increasing your income so that you can save. The Save phase focuses on savings (and spending) behavior. The Grow phase is where the portfolio’s investment strategies matter. And the Preserve phase is about managing the upcoming retirement transition. For retirement advice to be effective, it must be paired to the appropriate phase.

So what do you think? Does the “Earn, Save, Grow, Preserve” framework seem like a relevant way to discuss accumulating for retirement, to focus in on the right issues for the retirement accumulator? Are there any gaps in this approach? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!

Mr Kitces, I like this way of thinking about how to prioritize your efforts. I am not sure I’d use it as my primary framework, but I absolutely plan to use it as a framework for talks with my kids, thank you! I think all 4 elements are important in one form or another for most of your pre-retirement life, but looking at it this way drives thinking about a range of important issues and forces you to build a complete plan…. One can easily dive into many many additional (more focused) discussions off of these charts. I do think your comments about life events are particularly important. We have a special needs child that definitely strained our resources at times, and have had to adjust, & that’s a very long discussion, but legacy/wealth preservation is a key issue.

My other child just got his first summer job. Half of his earnings will go into a Roth IRA. We don’t have the cash flow yet (but very soon!) to ‘match’ it in real time, but we think of the funding of his 529 account as our ‘match’. My hope is to give him guidance such that he can be paycheck independent by age 40, and can choose the work he wants to do, remunerative or not. Doing so also means if he runs into life issues, he’ll likely still have a solid retirement, regardless of conditions (as long as he leaves that IRA alone!)

I think this is SPOT ON. It’s very similar to a model that I describe in my seminars, in which, “At every phase in your financial life putting your plan together is like putting together a puzzle. There are five pieces. Four of them are saving for tomorrow, managing debt, investing for the long term and protecting your assets. The size and shape of these pieces changes throughout your life, but these are ALWAYS the fundamental pieces, and they should fit together nicely–neither leaving gaps between them nor overlapping. The fifth piece is you, and each of the other four pieces should also fit you. Both the left side of your brain and your right.”

The model you describe here for transitioning retirement from a pure investment piece, to investing and saving, and finally to investing, saving AND protecting. Fits very nicely with what I teach clients and prospective clients. I’d be very interested in speaking/corresponding with you in more depth about this if you’re amenable to it.

I like the idea, though even for those that are just starting out and would be in the “Earn” phase, I always suggest that they try to set aside even $25 or $50 a month. For a couple of reasons. (1) It gets them into the habit of saving so that over time, they are used to it, and only have to increase the amounts, and (2) the sheer compounding that can occur from 25 through 65+ is so powerful (using the Rule of 72, the money early on could double 4 or more times with a roughly 7% return) that they really need to try to take advantage of it, even if at low levels of savings.

As you state, earning more is obviously vital long term, but starting the habit of saving, in my opinion, is also extremely important early on.

I certainly agree. I started a Roth IRA in college with $50/month. I wanted to started saving, but also start seeing the ups and downs of the market.

I LOVE the chart showing the effect of cash flow contributions vs. portfolio appreciation. I have young friends that stress out about what exact investments to make while they are only saving such a small portion of their income. As your post explains, young people should concern themselves more with making additional income and/or saving more of their income first.

I really like this. Spend less than you earn, invest the difference, eliminate & avoid debt has always been the financial drumbeat to which I march. It’s what I teach my kids, but it (1) assumes there is money to save and (2) doesn’t deal with preservation specifically. By looking at finances in these four phases you’ve covered the gaps.

My father gave me a retirement plan when i got my first summer job.

Save…

As much as you can.

As soon as you can.

As long as you can.

That was 48 years ago…he was right…!

Nope.

I agree that for a minority of Americans, successful retirement preparation is possible using the traditional approach: “… starting early, saving consistently, and letting compounding growth do most of the heavy lifting over time. …” And, I agree that for a different minority of Americans, successful retirement preparation is possible even following your four phases approach: Earn (find ways to increase income), Save (once you have discretionary monies), Grow, and Preserve.

Both savings strategies work for maybe half of all Americans. According to John Maynard Keynes the saving propensity of families is linked to one or more of the following purposes:

1. Precaution – To build up a reserve against unforeseen contingencies.

2. Foresight – To provide for an anticipated future relation between the income and the needs of the individual or his family different from that which exists in the present.

3. Calculation – To enjoy interest and appreciation.

4. Improvement – to enjoy a gradually increasing expenditure, (as a proxy for an improved standard of living even though the capacity to enjoy such spending may be diminishing).

5. Independence – To enjoy a sense of independence without definite intention of specific action.

6. Enterprise – To secure a mass of capital to carry out speculative or business projects.

7. Pride – To bequeath a fortune.

8. Avarice – To satisfy pure miserliness.

OK. Works for me and half of all Americans.

But, what about the other half – those who engage in economic activity that is short-sighted, those who are generous to a fault, those who miscalculate, those who make financial mistakes, those who suffer from innumeracy, those who engage in conspicuous consumption and extravagance. I would argue that, for that other half of Americans, neither of those two savings models – traditional or the four phases – will result in retirement preparation success.

Simply, more than half of all Millenials and Gen X’ers (even Baby Boomers) can’t wait for their incomes to rise – as, data show, we are at 1970’s levels of median household income. Oh, what to do! What to do?

For those Americans, I favor a third model, what I call “The 401(k) As A Lifetime Financial Instrument”. The concept is simple – at early ages (your Earn phase), develop a saving habit not specifically purposed for or limited to retirement. Get rid of “mental accounting”, or specific savings, specific-purposed accounts. Instead, save for all future financial needs. Focus those Americans on wealth accumulation, financial independence – not retirement. In fact, never mention “retirement” – strike that word from your marketing and communication materials used to communicate your 401(k) plan (I did that in launching new materials in 1996).

Then incorporate sensible pre-retirement liquidity features. Get rid of hardship withdrawals. Adopt line-of-credit, 21st Century loan functionality (the ability to pay bills electronically, to continue loan repayment after separation via ACH, and the ability to initiate a loan after separation). Remember, if retirement savings are limited solely to funding post-employment income, then, people will only save what they believe they can afford to earmark for retirement. For a 25 year old, we’re talking about money that she believes she will not need over the next 40 years. That is a very, very high bar to set, a commitment no 25 year old can reasonably make. If that is the trigger to start saving for retirement, no one will pull it until retirement approaches.

Many argue that “easy” access to retirement assets will simply increase consumption, and trigger greater debt not greater savings. However, studies show that 401(k) liquidity provisions tend to increase participation and contribution rates. Certainly, some stumble. But, most would have stumbled whether or not they saved in the first place – and without saving, they would have probably fallen into a deeper financial hole. However, to paraphrase Tennyson, it is better to have saved and lost, than to never have saved at all.

In the 1950’s, Nobel prize winner Franco Modigliani theorized a life-cycle theory of consumption or spending based on the observation that people make consumption decisions based both on resources available to them over their lifetime and on their current life stage. He argued that people build up assets at the initial stages of their working lives. Later on during retirement, they make use of their stock of assets. Important to his theory was that people tailor their consumption to match their needs at different ages, INDEPENDENTLY OF THEIR INCOMES AT EACH AGE. I believe this is the retirement preparation challenge for the other half of Americans. What you describe as: “The caveat to the traditional view on accumulating for retirement is that in reality, an individual’s income, spending, and ability to save vary greatly throughout life.”

Finally, I agree that “the best advice to save more for retirement is to earn more so you can save in the first place!” But, where that is not possible, and it is not likely possible for half of today’s American population under the “new normal” of <2% GDP growth and lagging productivity, a third solution is needed – what I would call the “Bank of Mike”:

1. Earn

2. Save in your 401(k)

3. Get the employer match (if any)

4. Invest, accumulate a balance

5. Borrow to meet immediate need

6. Continue to contribute while repaying the loan

7. Rebuild the account, for a future, greater need

8. Repeat as needed up to and through retirement

So, if you can, use the traditional method. And, where the traditional method doesn’t work, use the phased approach. But, where neither works for you, try the “Bank of _____”, use your 401(k) Plan As A Lifetime Financial Instrument, as an aggregator or consolidator of all personal wealth – while working, during retirement, ending only at death.

I have been fortunate and smart in life, and now have accumulated quite a nest egg. Although still in the “grow” stage of my life, I see already where additional savings make very little impact on my portfolio. It’s all about letting the portfolio earn money on money. That’s where my net worth is jumping. I sometimes experience single days in my portfolio that I earn (or lose) more money than I made my first year out of college.

As always, a good article that’s simple yet effective.

Couple of additional items I’d add for younger clients in the “earn phase”:

1) Get a budget: cash is king and expenses drive everything; no matter what phase of life your in. I have a lot of friends who are amazed at how much money they actually have available for saving after creating a budget. Personally I use a simple bucket strategy of 60/20/10/10 that’s allocated towards expenses, retirement savings, emergency fund, and discretionary spending, respectively. The beauty is that you can tailor the percentages to your individual needs and adjust overtime. My budget is also fully automated so I don’t have to worry about paying bills on time or transferring money. Lastly, I use online banks Schwab & Ally because of their ATM fee reimbursement, free checks & money transfers, and no monthly minimums.

2) Save and invest early: the importance of compounding growth in your early 20’s can’t be overstated and by far your most important asset at this stage of life is time. Even just $50/mo can have a huge impact overtime because the longer you delay, the longer/higher your contributions need to be in order to catch up; assuming your investment strategy is the same. And on that note, investing in low-cost and broadly diversified market cap passive ETFs and index funds is your best option (yes, that’s my bias). Resources such as Vanguard, Bogleheads, Rick Ferri, Mark Hebner, etc. are all great resources to learn more about investing.

3) Diversify your cash flow: one of the best lessons I ever learned came from Mark Branham, CFP(r). The lesson was simple, “develop multiple streams of cash flow (i.e. side hustles) that way you have more money to save/spend, as well as protection in case you lose one of your primary streams of cash flow (ex. your day job). For example, I played college lacrosse and became a referee as a summer job. I still officiate to this day and make about $8-10k/yr doing it. When I was laid off about 9 months ago, I barely had to tap into my emergency funds thanks to this side hustle in conjunction to my severance and unemployment benefits. Eventually I got back on my feet within a couple months and now all the money goes towards its original purpose of either additional savings, replenishing my emergency funds if needed, paying off high interested rated debt (if any), or more recently paying for my Master’s degree.

Overall, we’ve heard this advice a 100x over, yet we still have a tendency to overlook and take it for granted because it’s plain-vanilla. However, sometimes simplicity is the ultimate form of sophistication because becoming wealthy is not a fast, complex, and exciting event like Hollywood makes it out to be. In fact, more often than not it’s a long, slow, diligent, and sometimes boring process that’s easy to lose focus on. That said, nothing is promised, but following this and the aforementioned advice will really put you in a strong position to succeed because it’s the little things that add up to great things.

DJ

I am 32 and just started my true retirement savings last fall. It’s a small amount so far, but it is getting me used to volatility and practicing investing. I’ve been focused on expanding my earning potential and want to make sure I’m comfortable investing in practice before I see big gains in my earned income. I like your framework since it does not demand that we all need the same advice at the same time.

A good article about retirement investment plans hope to take some good help for investment with the help of your post.Thanks for sharing.

Kyle Rolek

Absolutely love this, especially the graphic “Contributions to annual increases in account value_investment growth vs cash flow contributions”. Would you be willing to share how you came up with this? I can’t tell if this assumes a certain fixed yearly ROI (APY) or if that somehow cancels out.

I have an excel sheet that looks at this from numbers as a function of yearly contributions (fixed) and a static rate of return (APY) – and it will flag you when your interest earnings exceed your contributions (and 2x, 3x, 4x your contributions). So a basic stab at the same idea and not nearly as aesthetically pleasing.

Very good article but I have to disagree that earning more is easier than cut spending. That’s a big fallacy usually spread by those who don’t work a w-2 job!