Executive Summary

Even though clients seek out and hire a financial advisor to obtain recommendations they can implement to achieve their financial goals, in practice clients often get stuck and resist taking action or making a change when the time comes. Sometimes the resistance might be based on cognitive or emotional biases, and other times it can be due to a lack of understanding or education about why the change is actually necessary or appropriate. Though in practice, with the range of potential reasons for clients to be resistant – despite having hired the advisor for advice in the first place – it can be confusing and difficult for financial advisors to know what to do to actually help the client move forward.

To help clients get over their resistance, advisors can use methods such as nudges, smart heuristics, and behavioral coaching. These methods have been designed not only to help advisors understand the client’s resistance but also to give them options for addressing the many reasons for the resistance, in a manner that aligns with both the client’s needs (as not everyone may need – or even want – behavioral coaching) and the advisor’s own capacity (advisors may not feel comfortable engaging with all of the available methods, and the time it can take in client meetings to do so).

Nudges are used to help automate processes and tasks for clients (e.g., those that clients must implement on an ongoing basis, such as automating monthly savings with a “pay yourself first” approach). They work best with clients who agree that the action is important and necessary, but who may simply need or want reminders or other mechanisms to help ensure the tasks get done. For clients who aren’t yet sure how to assess whether an action is necessary or important, advisors can use strategies involving smart heuristics, which are less about completing tasks and more about helping clients understand the issue so that they have the ability to engage in meaningful discussions with their advisor. Smart heuristics rely on ‘just-in-time’ teaching, which offers education on topics that the client is currently considering, and thus may find more relevant and meaningful.

For clients who have issues with resistance that stem beyond motivation or understanding, such as emotional biases or personal feelings, advisors can consider using an approach that involves behavioral coaching. Behavioral coaching helps the advisor guide the client to examine how their own emotions and thought processes impact their decision-making. For instance, many clients may be afraid to take action on their financial plan for fear of making a mistake. Accordingly, it is normal for them to hesitate out of fear, anxiety, or ambivalence when making financial decisions. Behavioral coaching can help clients overcome these roadblocks by slowing down to discuss the client’s hopes, dreams, fears, and concerns to ensure their plans are well-rounded and suitable for them. Because while it is important for a plan to be based on technically sound recommendations, the client needs to feel good about the plan and be on board with the recommendations in order for it to matter in the first place.

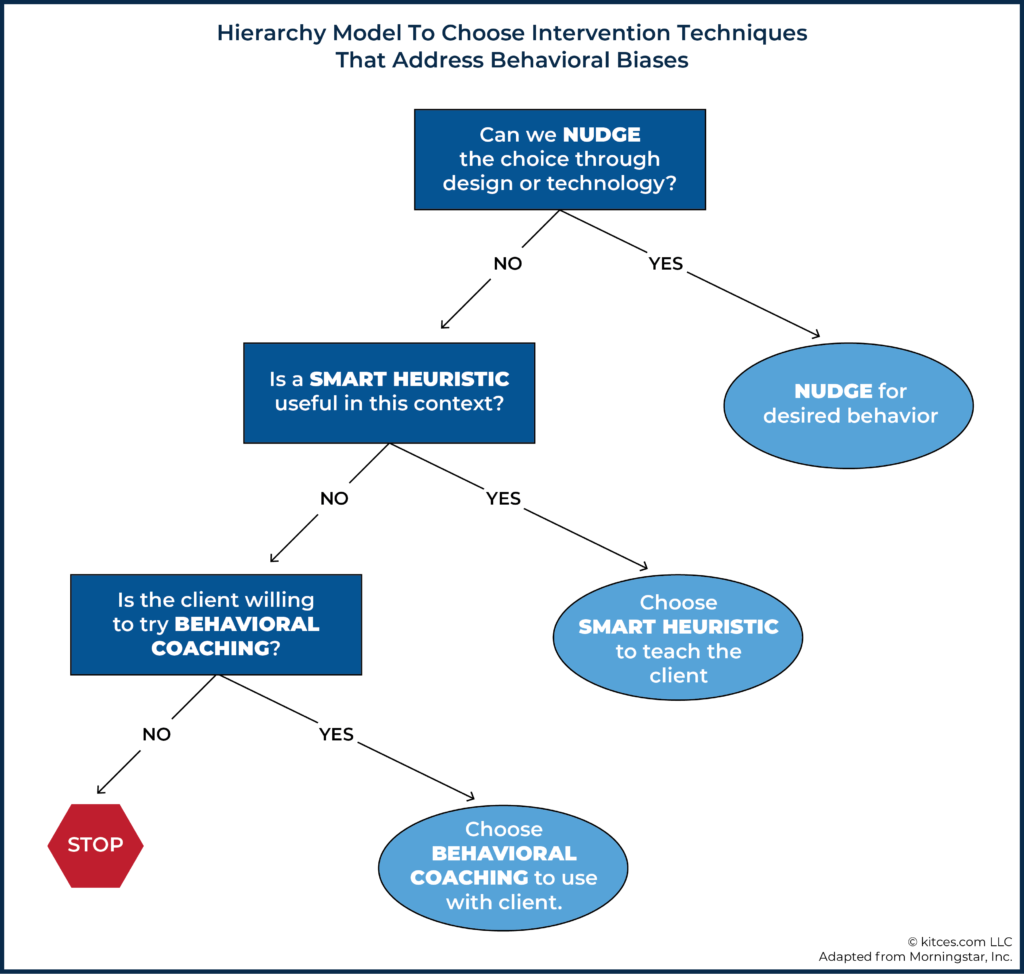

In order for advisors to choose which strategy to use with clients and when each strategy would be most effective, advisors can turn to a ‘decision tree’ model developed by Sarah Newcomb and Richard Cummings. The decision tree organizes nudges, smart heuristics, and behavioral coaching into a hierarchy that can be applied to each client’s circumstances, and sheds light on when to use one strategy over another. While nudges are helpful to simply remind clients that something needs to be done, smart heuristics can help clients understand an issue so that they can decide for themselves whether they want to take action. If neither a nudge nor a smart heuristic is sufficient to address the client’s resistance, behavioral coaching can help the client understand and work through deeper personal roadblocks.

Ultimately, the key point is that advisors have an arsenal of tools to help them work with clients who are struggling with resistance – stemming from a range of sources – that impede their progress in achieving their financial goals. By developing a plan of action implementing these tools with their clients, advisors can shed light on interesting and insightful details that can potentially result not only in the advisor creating an outstanding financial plan suitable for the client, but also in the client taking ownership over their plan and achieving their financial goals!

Financial advisors often find themselves helping clients who are resistant to making the changes needed to follow their financial plans and clients who find it difficult figuring out how to take action in the first place. And while teaching clients about the planning process can help clients understand their financial plans, education on financial planning principles alone may not always be enough to motivate clients to follow their plans.

Enter the book Financial Counseling (edited by Dorothy B. Durband, Ryan H. Law, and Angela K. Mazzolini), which provides a useful overview of three types of interventions in the chapter by Sarah Newcomb and Benjamin Cummings – nudges, smart heuristics, and behavioral coaching – that advisors can use to help clients who are resistant to change and/or finding themselves stuck. Because these clients will often be the ones who need the most encouragement and motivating support to stay on track with their plans when the going gets tough.

Nudges Can Only Do So Much To Overcome Client Biases

Research in behavioral finance has identified numerous biases that reveal interesting insights into why clients do what they do. Yet, identifying those biases is usually where the research tends to stop, as studies tend to be most concerned with trying to answer the question, “What processes does a person use to actually make a decision?”

And because the research has generally focused more on identifying biases that interfere with good decision-making, there hasn’t been much support for advisors seeking tools they can use to deal with these roadblocks to good client decision-making. This tends to be problematic because while advisors may be able to identify the bias, identification of the bias alone isn’t helpful for clients with behavioral biases that impede progress toward their financial goals.

An advisor who simply tells their client to stop behaving a certain way (with no explanation why the behavior may be detrimental), or that they are suffering from some particular behavioral bias (e.g., telling the client that their overconfidence is caused by the behavioral bias of being too trusting of a company just because they’re familiar with it), can come across as highly patronizing and will be more likely to offend (instead of help) the client. And even runs the risk of getting fired!

Understanding how to deal with clients who are stuck is important, as the problem is very common. In fact, research from therapy has suggested that close to 80% of therapy patients are not ready for change. Similar statistics can be found in behavioral economics research; for example, Daniel Kahneman wrote an entire book based on the many, many studies that he conducted with Amos Tversky over their careers, demonstrating that humans commonly make decisions based on biased decision-making systems that may lead to resistance to change.

For instance, if the client thinks their portfolio is fine because they know and trust the companies they are invested in (status quo bias/over-confidence bias/familiarity bias), they may be very resistant to the idea of selling those investments and making changes to diversify.

Fortunately, though, while the volume of research in behavioral finance, financial psychology, financial therapy, and behavioral economics provide ample support that financial advisors face real challenges when it comes to working with clients who are resistant to change (whether those challenges involve helping clients get past their behavioral biases or supporting them with the difficulty of implementing the change itself), there are solutions that advisors can use to help their clients overcome personal roadblocks and achieve success.

Why Nudges Have Limited Utility In Helping Clients Deal With Biases

For readers who may be thinking, “Well, one thing we can do for sure to help clients struggling with behavioral biases is in the name of this very section; we can use nudges!” ... you may be right, but only to a certain extent.

Behavioral finance and behavioral economics research has demonstrated that nudges can be a useful tool for advisors to help clients ‘sidestep’ biased thinking. Yet, while some nudges can be valuable to help clients in some instances (e.g., automating simple, routine tasks that the client does not need to think about), there is less utility in nudges for advisors who want to educate their clients as a means to develop their financial self-efficacy.

For instance, consider the Type 1 nudge. These nudges involve automated processes and subconscious decision-making; they rely on classic choice architecture, which means that there is no teaching involved. Instead, Type 1 nudges simply take the cognitive load off clients by eliminating their need to make any tough decisions in the first place.

An example of a Type 1 nudge is setting up automatic transfers into a client’s savings account (a “pay yourself first” approach to saving). While automatic transfers can truly be effective to help the client meet savings goals (as clients generally don’t need to exert any effort or struggle with willpower, brainpower, knowledge, or ability to actually ensure those transfers are made – the automated process does everything for them), there are few (if any) lessons that the client learns from these Type 1 nudges about how to better manage their financial behaviors in the future (instead, they’re simply bypassing the problem, with an out-of-sight-out-of-mind approach).

On the other hand, Type 2 nudges are different from Type 1 nudges because they require the client to engage in more deliberative action and conscious thought. For example, useful Type 2 nudges in financial planning are commonly found in what are known as “pre-commitment strategies” (where clients determine and commit in advance to certain actions that will be taken in the future, which makes it easier to stick with them and follow through when the time comes if only to not be seen as flip-flopping on their prior commitment), such as rebalancing guardrails and the guidelines outlined in Investment Policy Statements.

Type 2 nudges often require the client to contemplate their actions and different scenarios they may face, and to actively engage with their planner upfront (to determine what to pre-commit to in the first place) but are generally used when stakes are low or when action isn’t needed just yet. It is much harder for clients (and humans, in general) to take action when they feel emotionally flooded. Accordingly, the strategy for using Type 2 nudges involves talking to clients and getting commitment early, when they are not feeling emotionally overwhelmed.

For instance, it’s ideal for an advisor to discuss issues such as rebalancing rules or 10% guardrails long before the portfolio ever needs to be adjusted. Having the discussion beforehand, when there’s less potential for stress and emotional upset over an unbalanced portfolio, versus bringing up these important rules only after the portfolio needs adjustment, precludes the client from being pressured into taking action and agreeing to a rebalance in the moment when their portfolio crashes.

Type 2 nudges, therefore, can be a useful tool to provide time and space for more balanced conversations where emotions may still run high (money can be a stressful topic for clients, and their stress levels can rise even further when their portfolio has had a loss), but not to the point of clients shutting down altogether and ‘freezing’. Moreover, in the example of Investment Policy Statements, Type 2 nudges encourage clients to commit to an investing strategy before the need for rebalancing ever comes up. Then, when the portfolio does need to be rebalanced, having the pre-committed agreement already in place can make the ‘when’, ‘how’, and even ‘why’ of the rebalance a lot smoother. Although it probably won’t eliminate all questions or objections.

So how can advisors use nudges as potential solutions when working with resistant clients? While both Type 1 and Type 2 nudges primarily focus on getting the client to take action, they do it in slightly different ways. While Type 1 nudges are useful for helping clients to take immediate action on their plan with a minimal investment of time and effort, Type 2 nudges are used when advisors want to educate clients and when action is not needed right away, in order to ensure clients can take action in the future.

Furthermore, given that the objective of nudges is generally for the client to take action – and not so much to educate the client – nudges are best suited for those clients who are actually ready for action. For instance, Type 1 nudges may help clients with a savings goal by setting up automatic transfers. While they may help the client stay on track with their plan by successfully saving up money, nudges don’t actually teach clients about establishing new habits. And while Type 2 nudges may serve to educate the client so that they can think deliberatively about their actions, the focus is still on taking action to stick to the plan. And, of course, clients who listen to their advisors and do what they need to do to stick to their plans are great clients. If this is the objective, use nudges.

Conversely, if your client isn’t quite ready to jump in and take action (e.g., if they hesitate even with the support of a Type 1 nudge, or they won’t agree to the Investment Policy Statement and prefer to see what happens before they commit) then a nudge is not going to do much good. Your client clearly wants more time to think… and that isn’t a bad thing! Because thinking clients – thoughtful clients – present opportunities to deepen the client-advisor relationship, foster personal financial self-efficacy, and learn.

Smart Heuristics And Behavioral Coaching To Address Clients’ Biases

So if nudges (especially Type 1 nudges) are not always the way to go – at least when the financial advisor wants to focus on education and the client isn’t ready for action – then what can the advisor do to help clients work through behavioral biases preventing them from staying on track with their financial plan?

Two techniques presented by researchers Sarah Newcomb and Benjamin Cummings, and highlighted in the book Financial Counseling, include 1) Gerd Gigerenzer’s concept of ‘smart heuristics’ and 2) behavioral coaching. Both can offer the benefits of nudges (helping clients comply with the advisor’s recommendation) but actually engage clients along the way more by focusing on the role of the client’s behavior, which is a bit different from the up-front engagement and agreement (pre-commitment) present in the Type 2 nudge, which focuses more simply on the action to be taken.

For instance, a Type 2 nudge is designed to engage the client to work through and think about the choice or action to be made in the future, in areas in which they are already (ideally) knowledgeable (most likely because their advisor has explained the concepts and the process that they will take in the future when X happens). The objective of the Type 2 nudge is not specifically on educating the client (although there may be an educational component involved), but instead it is on preparing them and encouraging them to take action on their plan in the future when the time comes.

Smart heuristics, on the other hand, are more about educating the client. They employ just-in-time education strategies to make the education being offered more relevant, since they involve topics that the client is already currently considering (but may not be quite ready to take action on). Smart heuristics give the client information they can use to actually engage and take part in discussions about topics they need to act on in the near future.

Behavioral coaching also engages, but with more than just education. Behavioral coaching is largely about taking the time to carefully listen and understand the client’s needs, perspectives, questions, and concerns. This often happens even before any action is required, at least initially, and helps the client understand and work through the emotional issues and thought processes that may be impeding their progress.

It’s important to recognize that while smart heuristics and behavioral coaching both involve giving advice to clients, the primary objective of these techniques is not on the advice being given. Instead, the primary objective is to address the client’s behavior and motivation. Accordingly, the advice given when using these techniques may be greatly effective in helping the client take action, but may not necessarily encourage the best course of action in terms of the client’s financial situation.

Advisors must ultimately assess when motivating the client with potentially “suboptimal” advice is still more valuable to the situation (because they make some progress and get away from an even worse situation) than giving what the advisor believes is really the “best” advice for the plan (but may be a moot point if the client is not motivated enough to actually follow it!).

Smart Heuristics Offer Clients A Frame Of Reference For Meaningful Engagement

Smart heuristics are simple guidelines intended to be used as easy-to-remember rules, similar to mnemonic learning devices, and sometimes simply referred to as “rules of thumb”. For example, “save 20% of your income”, “rent should not exceed 30% of your gross income”, and “subtract your age from 100 to derive your portfolio’s stock allocation” are all considered smart heuristics.

They are often intended as reminders or easy ways to make estimates; accordingly, as most advisors recognize with rules of thumb, they will not always be perfect for a particular client situation. However, they can still be very useful, especially when they give novices some frame of reference about something they don’t yet understand, which can help them feel more comfortable about joining conversations about topics that are unfamiliar to them.

For instance, a client may feel ashamed to say that not only have they not saved enough for retirement, but they also don’t even know how much they should be saving. By offering the smart heuristic that recommends clients should save 20% of their income, the advisor gives the client a starting place to be able to actually engage in the savings discussion.

This can lead to a very different (and much more productive) conversation than the client simply saying, “I don’t know how much I should save.” Because with a smart heuristic, the advisor can facilitate a much more productive conversation that might go something like, “We commonly see successfully retiring clients typically having saved at least 20% of their income during their working years. What do you think about using a similar approach in your situation?”

When it comes to encouraging clients to take action on their financial plans, smart heuristics can be used to help clients understand the issue at hand so that they can feel more confident about making an informed decision based on what they now know. Smart heuristics can be especially effective here, as the teaching is very focused and offered at the precise moment when it is actually needed (versus earlier on, such as when trying to encourage proactive intervention). This is referred to as just-in-time teaching.

For instance, imagine working with a client that has expressed interest in buying their first home. The client has already started saving up for their goal; accordingly, they are primed to learn about how mortgages work, and what interest rates mean, in the context of their financial plan.

Clients in this frame of mind will be most receptive to education about mortgages (education they might have ignored in the past, even if they had access to a financial literacy program, because it simply wasn’t relevant to them at the time), which presents an opportunity for the advisor to use just-in-time teaching. After all, financial knowledge is not usually retained when it is given too early in the process, anyway; thus, again, the client would have been more likely to forget, or simply to disregard, any information they tried to learn before they were seriously considering the purchase of a new home and needed to know how it all works.

So why do simple heuristics work so well? Basically, they work because they are offered at the precise moment when the information is most relevant to the client. They are designed to be easy to digest and remember and, therefore, are very effective for getting clients engaged in relevant financial topics.

Again, people generally don’t like to talk about money; one reason for this is because they believe it is too complicated. Using simple terms, simple math, or simple rules allows clients to better understand the various outcomes associated with a decision, making it easier to engage in the conversation than poring over a more-technically-accurate-but-also-more-difficult-to-comprehend detailed financial planning projection.

Even if the advisor doesn’t like to offer smart heuristics to clients who need more personalized approaches, discussing the heuristic itself can be a great place to start the conversation. If both the client and the advisor know that 20% of income is a good savings goal, then having a discussion about whether 15% is enough, or if 30% would be better, takes the simple opportunity to educate further – but starting with the smart heuristic can lay the groundwork to get things started.

How Financial Advisors Can Use Smart Heuristics To Involve Their Clients In The Decision-Making Process

While smart heuristics might not be the appropriate approach to use all the time, they can offer the advisor an opportunity to help the resistant or ambivalent client by increasing that client’s financial knowledge and ability so that they can further engage in a meaningful discussion.

For example, a conversation applying traditional advice, without using a smart heuristic to help engage the client in the discussion, might look something like this:

Example 1: Bill is a financial advisor and is meeting with his client, Ted. Ted is considering a mortgage to purchase his first home.

Bill: Thank you for coming in today, Ted. I looked over the three mortgage options that you sent over, and based on our spreadsheet analysis, I think you should go with number 2.

Ted: Great, thank you for taking a look. I really appreciate your advice.

By contrast, the goal of a smart heuristic, by using just-in-time teaching, is not to tell the client what to do, but to bolster their ability to understand finances and make their own decision.

Example 2: Frank is a financial advisor and is meeting with his clients Chloe and Clayton. The couple is considering a mortgage to purchase their first home together.

Frank wants to engage Chloe and Clayton in a discussion to make sure he fully understands their situation and concerns, and also to help them better understand how a mortgage would impact their financial situation.

Frank: Thank you for coming in today, I looked over the three mortgage options that you sent over, and I am ready to discuss them.

I have two guidelines for you to consider, simply to give you a frame of reference about how your mortgage will fit in with other household expenses and liabilities:

- Maximum household expenses shouldn’t exceed 28% of your gross monthly income; and

- Household debt shouldn’t exceed more than 36% of your gross monthly income.

These guidelines are just something to consider as we take a closer look at these three options alongside your income statement.

Chloe: Great, we can remember those guidelines! But our situation is a little different from the average couple. We might need to adjust them further.

These are simple examples, but the point is that the smart heuristic dialogue in Example 2 offers the client some general guidelines to establish a frame of reference to help them understand the topic and to give them a starting point to engage in the conversation (though it may not be the endpoint as the clients adapt the rule of thumb to their individual situation).

And by encouraging the client to engage in the conversation, the advisor also involves the client in the decision-making process. In the end, this serves to facilitate a more meaningful discussion of the issues around the specific advice for the client and allows the advisor to encourage clients to implement what they’ve learned, trusting that the client has a good grasp on why they need to take action.

Ultimately, the question for advisors to consider when choosing which tool to use really depends on where their clients are in the decision-making process. If clients are struggling to make a decision because they lack knowledge around a certain issue, a smart heuristic will help the client overcome that bottleneck by giving them the tools they need to engage in discussions to better understand the issue.

On the other hand, if clients are on board to proceed with taking action but need help remembering to do so (or desire a systematic way to ensure the action takes place when the time for action does arrive), a Type 2 nudge can ensure that action will be taken with the client understanding the issue and why they are taking action.

However, if the client is struggling to take action because of emotional roadblocks, then behavioral coaching, discussed next, may be the best solution.

Behavioral Coaching Can Help Clients Understand How Their Feelings Align With Their Financial Goals

Behavioral coaching is another technique that advisors can use in lieu of (or in addition to) nudges and smart heuristics and involves taking the time to more carefully explore the emotions and thoughts that influence a client’s judgment and decision-making behavior.

Behavioral coaching can be developed into a structured program, or it could be carried out more informally simply by devoting a few extra minutes during the meeting with the client specifically to discuss the client’s feelings and thoughts about their plan. With this approach, advisors aim to facilitate change by helping the client find their own way forward, by encouraging them to tune into their own feelings and thoughts about their situation, not just by simply encouraging the client to follow what they have been told to do.

This does not necessarily mean the client will act in opposition of their advisor; rather, the goal is to help the client develop insight into what they really want and why they want it. Perhaps this means the client will realize there are more important reasons behind their goals that they (or the advisor) hadn’t considered before, or that there may be a different path to achieve the goal that the client is more excited about or more comfortable with.

As such, behavioral coaching offers the advisor a tool to guide clients by helping them to explore their own genuine ideas, not just providing them with pragmatic instructions or the advisor’s expert suggestions that may not actually align with the client’s own point of view.

Understandably, behavioral coaching will take more time than using smart heuristics or nudges, as it can take a lot of patience to temporarily set aside financial plan action items to slow down and have a conversation with the client about their feelings. However, behavioral coaching can be an extremely powerful tool to help clients who want to take action but still need to identify the best way forward. And while this approach does take more time and may cause things to move much slower, the results of behavioral coaching can be quite impactful for the client, with longer-lasting effects.

In essence, behavioral coaching empowers clients to become the heroes in the story of conquering their own challenges by helping them understand and overcome the emotional and mental barriers that may otherwise keep them from achieving the goals set out in their financial plans.

For instance, imagine that the client couple from Example 2 above, who were considering a new home purchase, chose a mortgage lender but then froze before signing the agreement and backed out of buying the home. The couple decided that they just couldn’t bear handing over such a huge down payment that they worked so hard to build when the housing market and economy felt so uncertain.

In this example, the client is scared and, most notably, they are stuck. They are not moving forward, and they are afraid to take action… in fact, they are on the verge of back-pedaling. An advisor could use behavioral coaching by placing more emphasis on the personal trust established with the client to explore the client’s feelings and emotions about the home buying process, in contrast to introducing timely information and educating the clients about how mortgages work (e.g., smart heuristics, such as just-in-time teaching to convince the client they are making a good decision) or using default options to simplify the mortgage lending process (e.g., Type 1 nudges that automate processes with minimal effort from the client).

As advisors know, some clients consider owning property as an important aspect of building wealth and thus may think that buying a home is simply the right thing to do. They may not necessarily need to – and some clients may not even really want to – buy a home! Homeownership is not the golden rule and it may not be for everyone.

And by helping the client sort through their own beliefs about homeownership and why (or whether!) the need for a home is important to the client, the advisor not only helps the client make the right financial decision, the advisor can even help to protect the client’s mental health! Because choosing to buy a home and taking out a large mortgage to finance it, regardless of how good the mortgage terms may be, will likely just end up in a lot of emotional distress if the client’s heart is not genuinely vested in being a homeowner.

Using Behavioral Coaching To Help Clients Design Meaningful And Sensible Financial Plans They Will Follow

The goal of behavioral coaching is to work with the client, ultimately guiding them to identify their own next steps that make the most sense for them… and not just giving them instructions to follow. However, the advisor can (and should!) still give advice in these situations to ensure they are steering the client in the right direction.

Consider this example of an advisor offering ‘traditional’ advice to a fearful client:

Example 3: Scott is a financial advisor meeting with his client Jean, who is thinking of purchasing a new home but needs guidance about which mortgage she should choose.

Scott: Thank you for calling and letting me know what is going on; I know you are really stressed about buying a new home and that these are crazy times for you. I want to reassure you that we went over the numbers very carefully and have determined that you can afford to buy the house, and this is the right mortgage for you.

Jean: Great, thank you for taking a look. I appreciate your advice, and I will get in touch with the mortgage lender.

Several weeks pass, and nothing happens. When Scott calls Jean to follow up, she tells him that she hasn’t gotten around to calling the lender yet, but that she will eventually.

In truth, Jean feels ambivalent about taking action, even though she trusts Scott and feels he has done his best to give her the right answer.

Scott senses Jean’s hesitation to follow through and thinks about implementing some behavioral coaching in his next meeting with Jean.

In this example, the advisor did nothing wrong during the meeting with the client. He was kind, thanked her for sharing something that had taken quite an emotional toll on her, and reassured her that she was making a smart decision. He did the proper analysis and came up with the technically correct recommendation. However, the advisor also recognized that simply giving his client the ‘right answer’ wasn’t helpful in getting the client to take action on his advice.

Behavioral coaching facilitates space for the client to explore their emotional motivation behind their financial goals, using introspection to guide them forward.

Example 4: Scott, from Example 3 above, decides to invite Jean in for a follow-up meeting and wants to implement some behavioral coaching techniques to better understand Jean’s hesitation. Their conversation goes like this:

Scott: Thank you for coming in again to review your mortgage options. I know you’ve been busy and haven’t gotten around to contacting the lender, and I just wanted to take a bit of time to make sure we’ve really identified the best choice for you. I’d like to hear more about your feelings around the process so far.

Jean: Great, thank you. To be honest, I just couldn’t follow through with making the down payment for the mortgage. It was just too large of an amount to be comfortable with. It freaked me out just to think about parting with that much money.

Scott: So I hear you saying that it was the idea of parting with the down payment, to use your words, and that it would be painful not to see that money in your bank account. Is that right?

Jean: Yes, I mean…I know it is not really gone… since it would be invested in the house. But I just feel like that money is all that I really have, and to wrap it all up into a house really makes me worry… what if something goes wrong?

Scott: Correct me if I am mistaken, but it seems like some of this could be solved by perhaps finding a less expensive house, or maybe even opting for a mortgage with a smaller down payment, even though it would mean a larger ongoing monthly payment, so that you can maintain some of your savings. How do you feel about those suggestions?

Jean: Yes! I mean…I really like the house I found, but I just can’t seem to pull the trigger when it comes to letting go of the down payment. I know it would be a big pain to start the whole process over again, but I think that is what I might be leaning toward.

Scott: We could make that work if that’s what feels right for you – we can certainly adjust your financial plan to accommodate that. Another idea to consider would be to set up a savings plan to replenish your savings to a level with which you are comfortable and then to pull the trigger on the mortgage. Interest rates do vary, so we might not have this exact same option next time around, but we will certainly find something that you are truly comfortable with, and that is what really matters.

Jean: I really like both of those ideas. I feel better already, and will think about these options more carefully. Thank you.

Sometimes, effective behavioral coaching can even actually lead to a different – and better! – ‘right’ answer; as while there may be one solution that is feasible from a financial sustainability perspective, another solution that may seem less appealing to the financial advisor might actually be better for the client from a practical perspective simply because it resonates perfectly with the client’s wishes and underlying emotions!

The Hierarchy Of Helping Clients Overcome Their Behavioral Biases

Armed with these three strategies – nudges, smart heuristics, and behavioral coaching – how do financial advisors decide when to use them and which ones to use? Because certainly, there is an appropriate (and inappropriate!) time and place for each.

To address this question, Newcomb and Cummings created a hierarchical model for ‘layering’ these techniques, and how to think about when and how to use them. The model is very helpful as it aligns a useful tool/technique (e.g., nudge, smart heuristic, or behavioral coaching) with what clients are actually doing (or not doing). This can help guide financial advisors, firms, and clients through an organized process of taking action as the issues faced by advisors, firms, and clients evolve, grow, and change.

The hierarchy is essentially a decision tree that the advisor or firm can use to decide what form of intervention will work best by answering a series of quick questions about what the client is (or is not) open to. For instance, the situation may need no more than a simple nudge to help the client overcome barriers they don’t want to spend a lot of time on, or if a nudge isn’t appropriate, then a smart heuristic may be useful for clients who are considering action but still want and need a little information to feel invested. Alternatively, if the client needs more internal work (and if they are open to doing that work), then behavioral coaching might be the right approach.

A Framework For Advisors And Firms To Implement Intervention Strategies

By using this hierarchical framework of intervention techniques to help clients overcome their behavioral biases, advisors and their firms can systematically decide how far down the decision tree they even want to go. As the strategy might be to employ nudges and smart heuristics when they are appropriate tools to help the client but not to use behavioral coaching because the approach is simply beyond the reasonable scope of potential activities the advisor or firm is willing to take on, given the very time-intensive nature of the technique.

Alternatively, some advisors and firms may agree that all three techniques can be implemented when appropriate, and might consider establishing a system of certain limits on how much time advisors should devote to behavioral coaching, depending on the client and circumstances.

While not all financial planners and firms, depending on career stage or practice style, may have a feasible way to include (and get paid for) a formalized behavioral coaching program as part of their services, behavioral coaching can still be offered in a more casual, impromptu manner as the need for it arises; the hierarchy can be used to work with a client’s mental blocks in ways that can serve the advisor, the client, and the practice.

For example, the decision tree can be used to set up new client-advisor relationships (e.g., standard nudges can help clients complete on-boarding paperwork), and during subsequent client meetings (e.g., having an established handful of smart heuristics on hand during client meetings can be used to help clients struggling with certain topics to understand enough to engage in the discussion). And perhaps separate follow-up meetings can be scheduled with clients when behavioral issues are identified during their routine meetings, so the advisor can give the client ample space and time to use behavioral coaching to help them through their roadblocks. Use of the decision tree can even be implemented as a firmwide protocol, so everyone is on the same page about the value-add that can be provided with the tools to address different types of client behaviors.

The hierarchy is flexible and can be organized around both the advisor’s and client’s comfort zones (and capacity). Accordingly, there is no reason why this process should be hidden from clients. It is a roadmap to use when working on all sorts of issues – good or bad – and helps to keep the advisor-client relationship fluid. The model can also serve as a reminder for advisors to stop if the client does not want behavioral coaching (because coaching should never be forced onto a client who does not want it).

Introducing the decision tree to clients to keep things transparent can also help clients understand the advisor’s intentions to help them through their behavioral biases. Advisors don’t need to bust out an image of the hierarchy to share with the client during a meeting (although possible… though it might be awkward). Instead, simply telling the client that the firm has established processes and tools for working with clients that include things like nudges, smart heuristics, and even behavioral coaching in an introductory meeting can be a great way to introduce these topics.

Clients may or may not be interested to discuss or hear more. The important point is that you mentioned it so that when it comes time to use one of these tools, the client will already be familiar with the strategy. Because a good way to help clients accept behavioral coaching or nudges is to tell them upfront that your firm employs them for all clients in the first place… before the nudges or coaching are ever needed.

Another way to make the introduction can involve offering a ‘behavioral contract’ for clients to sign, so they can acknowledge that they are aware of these strategies. As with an Investment Policy Statement or rebalancing agreement, the client does not have to go through with anything they do not want to. But by simply discussing and signing the ‘behavioral contract’ that describes different ways of working together and different behavioral tools, clients might be more willing to give it a go.

These methods for normalizing these processes and tools (talking about the fact that your firm works with clients in multiple ways as well as potentially using a behavioral contract) from using nudges to behavioral coaching – can be great ways to initiate the discussion during the tough days when internal issues such as difficult emotions and problematic biases need to be addressed.

Furthermore, the decision tree can even provide a convenient system that anyone in the firm can use to address and document work with clients over time, which can be a useful tool for compliance purposes.

Clients are going to struggle with implementing change to realize their financial planning goals; humans are simply wired to behave this way. Sometimes the struggle relates just to getting started and finding the willpower to do so, sometimes it relates to knowledge and confidence, and other times it involves emotional roadblocks.

Moreover, while the struggle is normal, when clients do struggle, the situation can be tough, and it can be difficult for the advisor to decide what to do and when to do it. Thankfully, for advisors, the Newcomb and Cummings hierarchy organizes what to do and when to do it in a simple, straightforward fashion that employs some of the best tools and techniques to work with struggling clients. Advisors can introduce the hierarchy early on to normalize the fact that change is hard and to show clients that solutions involving different approaches are available to help.

By helping clients get unstuck and work through their resistance, advisors can grow and deepen their relationships. While the process may require some time commitment, using the decision tree hierarchy can offer a simple approach for advisors to discuss options for behavior change with their clients, and finding the right solution for the client to ultimately realize their most difficult financial planning goals!

Awesome stuff Meghaan! Love the decision tree and how you’ve highlighted the differences between nudges, educating clients & behavioral coaching.

For those actions that clients need reminders on to avoid what Dr. Somers likes to call “unintentional non-adherence” we’ve built Knudge to help. We’d love to show you what we’ve built if you are interested in a demo let us know: https://knudge.com/#Demo

Your example of not following through on the mortgage process highlights one other benefit we’re seeing. Advisors have said that the insight into what tasks aren’t completed allows them to identify where other intervention (education or behavioral coaching) may be needed on a topic.