Executive Summary

Loss aversion—the idea that losses hurt more than gains feel good—is one of the most well-known insights of behavioral economics. Originally developed by Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky in the late 1970s as a component of “prospect theory”, loss aversion has since come to be seen as the driving force behind a wide range of phenomena such as the endowment effect, status quo bias, the disposition effect, and even the equity risk premium. However, a new article forthcoming in the Journal of Consumer Psychology makes the provocative claim that despite widespread belief to the contrary, losses are not actually more impactful than gains as a general psychological principle.

In this guest post, Dr. Derek Tharp – a Kitces.com Researcher, and a recent Ph.D. graduate from the financial planning program at Kansas State University – takes a deep dive into this provocative paper… examining the evidence on why losses may not truly loom larger than gains, and why it may be better to look at loss aversion as a concept that applies (only) in some specific circumstances.

In their forthcoming paper, researchers David Gal of the University of Illinois at Chicago and Derek Rucker of Northwestern University examine the history of loss aversion research, beginning with Kahneman and Tversky’s seminal paper and growing into one of the most widely accepted ideas in social science. Developed out of a need to address anomalies which could not be addressed by expected utility theory, Kahneman and Tversky provided a clever explanation for why loss aversion could result in people being risk averse when evaluating gains and risk seeking when evaluating losses. However, based on Gal and Rucker’s review of the research that has emerged since the development of prospect theory, as well as some of their own research which has attempted to isolate the effects of loss aversion relative to alternative explanations, the authors conclude that loss aversion has been greatly overgeneralized. Instead of being a general psychological principle, loss aversion appears to apply more or less based on the specific circumstances of a given situation, and it cannot be said that losses simply loom larger than gains.

As a result, financial planners should be careful not to assume that loss aversion applies in situations in which it may not. From career considerations to portfolio management strategies and even retirement income planning… clients may not actually be as loss-avoiding as we once believed, and the research suggests there really are situations where they may prefer to seek gains than to simply minimize risk of loss. Some more nuanced perspectives related to perceptions of losses and gains also provide potential insight for financial planners relevant to topics ranging from clients chasing gains to the ways in which financial planners sell and package their services. But ultimately, the key is to acknowledge that, despite conventional wisdom, losses may not truly loom larger than gains!

Loss Aversion and Prospect Theory

Of all of the insights from behavioral economics that have found their way into mainstream financial planning knowledge, perhaps none is more well-known than loss aversion—the idea that losses loom larger than gains (i.e., losses hurt more than equivalent gains feel good).

Though often confused with risk aversion, the two concepts are actually distinct. Whereas risk aversion is the preference for certainty over uncertainty (e.g., the preference to receive $20 over a 25% chance to win $100), loss aversion is the idea that losses result in more psychological dissatisfaction than equivalent gains result in satisfaction (e.g., the higher dissatisfaction associated with losing $20 relative to the satisfaction derived from gaining $20). As a result, loss averse individuals may be both risk averse when facing gains (i.e., willing to take a sure thing over a risky prospect) and risk seeking when facing losses (i.e., willing to take on extra risk to try and recoup losses relative to some mental reference point).

Loss aversion is an assumption originally embedded within a theoretical framework known as “prospect theory”. Developed by Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky in the late 1970s, prospect theory was proposed as a critique of expected utility theory.

Expected utility theory (EUT) was itself actually an enhancement over expected value theory. Under expected value theory, human beings are assumed to rationally evaluate the probabilities and expected ‘payouts’ of various outcomes – for instance, recognizing that it’s better to have a 25% chance to win $100 than just being given $20. However, because expected utility theory incorporates a utility function which can reflect an assumed level of risk aversion (i.e., to recognize that not all gains are equally positive), it is not necessarily a violation of EUT to choose $20 over a 25% chance of winning $100.

However, EUT still had issues which were widely acknowledged prior to Kahneman and Tversky developing prospect theory. Specifically, one such violation was what Kahneman and Tversky referred to as the “certainty effect”. Under the certainty effect, individuals demonstrate an irrational reversal of preferences when the probabilities of a certain and an uncertain outcome are proportionately reduced.

Kahneman and Tversky demonstrate this with a survey asking individuals whether they would rather receive (a) an 80% chance to win $4,000 or (b) a 100% chance to win $3,000. According to expected value theory, the rational thing to do is take risky proposition (a), as the expected value of (a) is $3,200 versus the $3,000 expected value of (b). Not surprisingly, given that people generally are risk averse, 80% of respondents chose option (b) (i.e., the majority of people were willing to trade off some upside in order to gain a certain outcome). So far this is not a violation of EUT, though it does illustrate EUT’s improvement over expected value theory by incorporating risk aversion.

However, Kahneman and Tversky then ask individuals whether they would rather receive (c) a 20% chance to receive $4,000 or (d) a 25% chance to receive $3,000. Notably, options (c) and (d) are merely options (a) and (b) with their respective probabilities divided by four. However, when presented with these choices, individuals reverse their preferences, with 65% of respondents choosing option (c) over option (d). Interestingly, when Kahneman and Tversky conducted the same surveys but in the domain of losses instead of gains, preferences actually flipped such that certainty became less preferable to individuals, who were who were willing to take a lower expected value gamble in order to avoid certain losses. While these are not the only anomalies which EUT could not account for, they are examples of cases in which risk aversion alone could not sufficiently address the choices that people seem to make in the real world.

Thus, Kahneman and Tversky came up with a clever solution in prospect theory. At the heart of prospect theory is the idea that, rather than evaluate ultimate outcomes, people evaluate gains and losses relative to some reference point (i.e., prospects) differently. Particularly relevant to the concept of loss aversion was the idea that the pain associated with losses is assumed to be greater than the pleasure associated with a gain of equivalent magnitude. As a result, the certainty effect could be explained by a preference to avoid losses relative to a reference point of a guaranteed $3,000, whereas risk seeking behavior in the domain of losses could be explained by a strong desire to avoid losses.

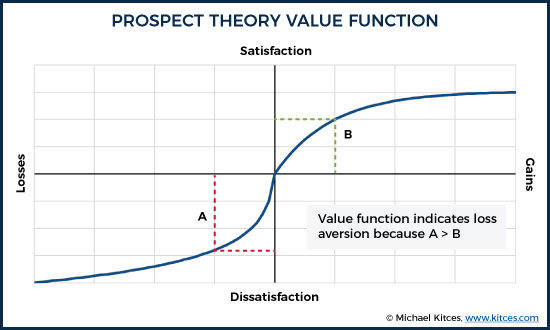

As you can see in the graphic above, the portion of the “value function” which represents losses (i.e., the portion of the function to the left of the y-axis) is steeper than the portion of the value function which represents gains (i.e., the portion of the function to the right of the y-axis). Which would mean that each “unit” of loss to the left of the center line produces greater dissatisfaction (the line falls more quickly) than each unit of gain to the right of center increases satisfaction. This is how prospect theory accounts for loss aversion, allowing the value function to differ between losses and gains, and particularly the steeper slope amongst losses which represents losses hurting more than gains feel good. Notably, whereas it’s the respective slopes among gains and losses that account for loss aversion, it is the different curvatures of the value function within the domains of gains and losses which represent the tendency for individuals to be risk averse among gains (concave down) and risk seeking among losses (convex up).

While there is more to prospect theory than just loss aversion, it is perhaps the most well-known finding of all of behavioral economics, and has found its way into many of the social sciences as well as pop culture. And loss aversion has generally been assumed to be a rather large effect which is highly persistent in many different areas of human behavior. In his book Misbehaving, Richard Thaler presents a rough approximation of just how much larger losses loom relative to gains, describing existing research by noting that “losses hurt about twice as much as gains make us feel good.” More generally, the concept is even captured in the wisdom of old adages such as “a bird in the band is worth two in the bush”.

While there is more to prospect theory than just loss aversion, it is perhaps the most well-known finding of all of behavioral economics, and has found its way into many of the social sciences as well as pop culture. And loss aversion has generally been assumed to be a rather large effect which is highly persistent in many different areas of human behavior. In his book Misbehaving, Richard Thaler presents a rough approximation of just how much larger losses loom relative to gains, describing existing research by noting that “losses hurt about twice as much as gains make us feel good.” More generally, the concept is even captured in the wisdom of old adages such as “a bird in the band is worth two in the bush”.

But is it possible that we’ve assumed that loss aversion applies more broadly than it truly does?

Do Losses Really Loom Larger Than Gains?

According to a paper by David Gal and Derek Rucker forthcoming in the Journal of Consumer Psychology, the weight of current psychological research does not suggest that loss aversion truly exists as a general psychological principle. In other words, while loss aversion may exist in some situations, there are too many situations in which the evidence does not suggest that losses actually loom larger than gains. For instance, as noted by Ert and Erev (2013), even if we’re loss averse when assessing certain financial wagers, it doesn’t mean we’re loss averse for all financial wagers, and other real-world behavioral phenomena—such as overtrading and a lack of diversification—can be seen as evidence against loss aversion. Therefore, we should not treat loss aversion as a psychological principle that can be relied on in all circumstances.

Gal and Rucker note that this is in stark contrast to prior research (and the pop culture view) which has described loss aversion as something that is present in all areas of life. In fact, the authors present an anecdotal example of a question posed at a 2016 conference on judgment and decision making, where attendees were polled and asked which of the following they believed:

- Losses loom larger than gains

- Gains loom larger than losses

- Losses and gains have similar psychological impact

The authors report that of the approximately 80 people in attendance, roughly 77 selected A, 0 selected B, and 3 selected C.

Why Losses May Not Loom Larger Than Gains

In their paper, Gal and Rucker consider two broad ways in which loss aversion could be defined: a strong form of loss aversion and a weak form.

According to Gal and Rucker, the strong form of loss aversion implies that “losses inherently loom larger than gains”. As a result, in order to accept the strong form of loss aversion as true, we should always observe that losses loom larger than gains when individuals are making decisions. Similarly, we should never encounter circumstances in which in gains loom larger than losses, or in which gains and losses are given equal weight. Gal and Rucker do add a caveat to this that measurement error or other factors could obscure our ability to see loss aversion in the real world (i.e., mistaken beliefs and perceptions about potential gains and losses could result in behavior that doesn’t appear to be loss averse even if the person is loss averse), but the strong form of loss aversion as a psychological principle would demand that people behave in a loss averse manner so long as they do properly understand the relevant gains and losses available to them.

Of course, this is a demanding conception of loss aversion, and it is often the case that psychological principles aren’t universally true. As a result, Gal and Rucker also consider a weak form of loss aversion, in which “losses, on balance, loom larger than gains”. The key distinction here is that rather than needing to be universally true, the weak form of loss aversion as a psychological principle only demands that losses would more commonly loom larger than gains. Therefore, the weak form of loss aversion allows the possibility that people may be gain seeking in some situations, but demands that the losses should still have a greater impact than gains more generally.

Ultimately, after reviewing the many strands of loss aversion research that have emerged since Kahneman and Tversky’s seminal article, Gal and Rucker conclude that neither the strong form nor the weak form of loss aversion is supported based on the research we have available. Instead, according to Gal and Rucker, loss aversion appears to be best understood as a psychological phenomenon that is dependent on contextual factors. In other words, in some cases we do see that people behave in loss averse ways, but how people evaluate the trade-off between gains and losses depends on their circumstances and other contextual considerations, rather than being a universal influence on all decision making.

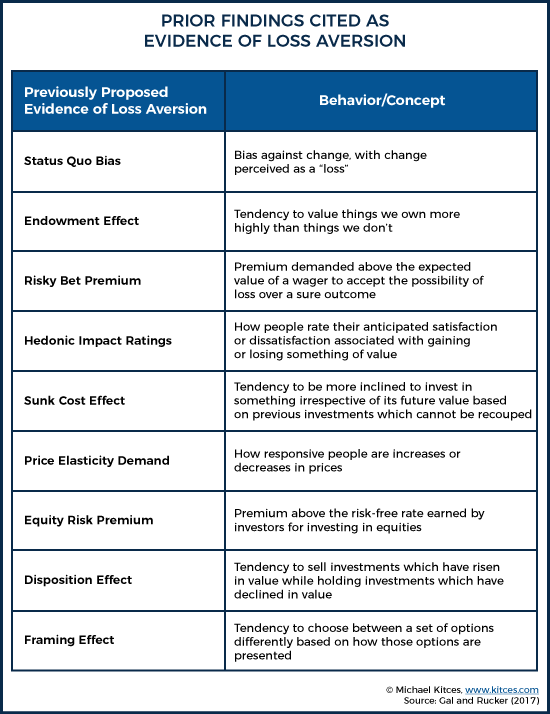

To reach this conclusion, Gal and Rucker review many different biases that have previously been attributed to loss aversion. Specifically, they review results from well-known studies that have typically been presented as evidence of loss aversion, including status quo bias, the endowment effect, the risky bet premium, hedonic impact ratings, the sunk cost effect, price elasticity, the equity risk premium, the disposition effect, and framing.

In each case, the authors present reasons to be concerned that the effects commonly cited are actually evidence of loss aversion. For instance, both the status quo bias (i.e., our bias against change) and the endowment effect (i.e., our bias to value things we own more highly than things we don’t) are both commonly presented as evidence of loss aversion.

Perhaps the most famous study on the endowment effect comes from Kahneman, Knetsch, and Thaler (1990), in which individuals demanded an average of about $7 to give up a mug they had been given (and thus they already owned), whereas individuals given an opportunity to buy the same mug were only willing to pay about $3. This has commonly been claimed to be evidence of loss aversion because, as Gal and Rucker put it, “the loss of the status quo option looms larger than the gain of the alternative (change) option”.

However, Gal and Rucker contend that in each case losses and gains are being confounded with action and inaction. Specifically, they present the following concerns for treating status quo bias and the endowment effect as evidence of loss aversion:

Loss and gain are confounded with inaction and action; when losses and gains are decoupled from inaction and action in the retention paradigm, no evidence for loss aversion is present (Gal & Rucker, 2017a). In addition, the status quo bias occurs even when the status quo and change options are otherwise equivalent and thus not coded in terms of losses and gains (Gal, 2006; replicated in this article).

In other words, prior research has not adequately distinguished between loss/gain and inaction/action. Or stated more simply, the findings of past studies may not be the result of fearing losses over gains, but simply the fact that people don’t like to change at all (regardless of the anticipated gain or loss outcome!). Gal and Rucker argue that these are actually distinct phenomena which must be examined independently… and once they are, the evidence supports “change aversion” but not necessarily any real loss aversion.

Accordingly, in a different (though currently unpublished) Gal and Rucker study, the authors attempt to better isolate change aversion by keeping end states constant across scenarios. The authors do so by comparing one’s willingness to pay to retain an item they already own (but will be lost if they don’t pay to retain it) versus willingness to pay to obtain an item they do not own. Thus, whereas the proposed end states in the classic endowment effect study are inconsistent (e.g., give up a mug and receive cash vs. give up cash and receive a mug), the end states are the same in the retain versus obtain comparison (e.g., give up cash and receive a mug vs. give up cash and receive a mug). This design forces individuals in the study to take action if they want to end up with the mug, and therefore provides a better assessment of true loss aversion.

If losses loomed larger than gains, we should expect that individuals are willing to pay more to retain an item that they will lose than they are willing to pay in order to obtain the same item.

Gal and Rucker note that there is a potential problem of perceived “fairness” in setting up an experiment this way. For instance, if people felt something was being stolen from them, then this too could interfere with assessing the concept of risk aversion. As a result, in the actual study, the authors use a series of different experiments evaluating scenarios such as the willingness to pay to fix a broken phone versus willingness to pay to obtain that same phone; willingness to pay to retain current internet service versus willingness to pay to obtain that same service; and willingness to pay (in time) to drive and retrieve a misplaced notebook versus willingness to pay (in time) to drive and receive the same notebook for free. In a slightly different experimental setup, Gal and Rucker even replicated the original mug experiment findings from Kahneman and Tversky before running a variation of the mug experiment which did not confound loss/gain with action/inaction.

The end result: once losses and gains are separated from action and inaction, Gal and Rucker find that the effects which are generally assumed to be evidence of loss aversion disappear. As a result, the researchers conclude that better designed experiments which don’t confound gains/losses with action/inaction challenges the standard conclusion that status quo bias and the endowment effect are evidence of loss aversion.

The authors similarly examine a wide range of research (far too much to cover here, but Table 1 of their paper provides a nice summary) that undermines the notion that risk aversion—in either the strong form or the weak form—is a general psychological principle. Instead, the authors conclude that loss aversion is a more nuanced topic that needs to be applied within the proper context.

How Loss Aversion Became Overgeneralized

Another interesting aspect of Gal and Rucker’s paper is their examination of the “sociology of loss aversion”. Specifically, the authors examine how loss aversion became so widely accepted despite lacking the actual evidence that would be needed to support that widespread belief (and even considerable evidence that should have resulted in questioning that belief).

First, the authors note the genuinely important contributions of early research on loss aversion. The concept of loss aversion did account for anomalies that existing theoretical models could not address. But based on a theory of scientific progress presented in Thomas Kuhn’s 1962 book, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, the authors note that the ascent of loss aversion (and potentially looming descent?) aligns with patterns of scientific progress that would be predicted by Kuhn’s theory.

First, the authors note the genuinely important contributions of early research on loss aversion. The concept of loss aversion did account for anomalies that existing theoretical models could not address. But based on a theory of scientific progress presented in Thomas Kuhn’s 1962 book, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, the authors note that the ascent of loss aversion (and potentially looming descent?) aligns with patterns of scientific progress that would be predicted by Kuhn’s theory.

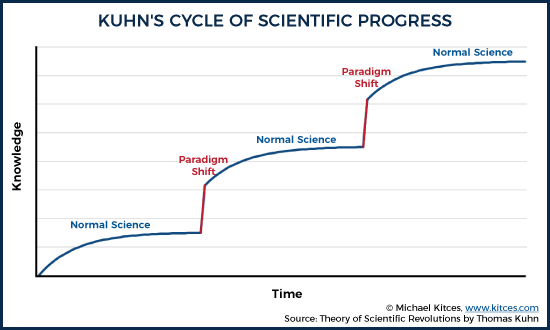

Specifically, Kuhn argues that rather than progress via a slowly accumulating base of scientific knowledge, much of the progress in science comes from “scientific revolutions” or “paradigm shifts”—i.e., leaps in knowledge which often arise out of “crisis” environments in which existing paradigms cannot adequately address anomalies.

This seems to map onto the rise of prospect theory (and thereby loss aversion) rather well. The flaws with expected utility theory (EUT) were well known, but researchers just weren’t sure what to do with them. Without a good sense of what to do about the anomalies, researchers just continued going about “normal science” (which Kuhn contends is general research work within an existing paradigm) within the dominant EUT framework. Yet, once Kahneman and Tversky provided a clever theoretical explanation for these well-known anomalies, a paradigm shift occurred, and prospect theory began to settle in as a new dominant paradigm.

Yet, a problem that can occur while fields are entrenched in the “normal science” of a given paradigm is that research can become somewhat self-reinforcing (e.g., researchers seek studies which easily fit within the paradigm or are consistent with the predictions of the new paradigm) while criticisms of the new paradigm can also be overlooked or hard to publish, at least in the short-run and until the newly dominant paradigm itself accumulates enough well-known anomalies to face the risk of being upended.

Gal and Rucker also note that loss aversion has a lot of intuitive appeal and is therefore particularly susceptible to overgeneralization. Gal and Rucker note that “loss aversion” as a concept even has some great branding, as its name can almost give the impression that it is obviously true (e.g., no one likes losses), but the more nuanced claims actually embedded in the concept of loss aversion (i.e., that losses loom larger than gains) can easily be missed.

From the perspective of the financial planner—who in many respects serves as an intermediary between financial/economic experts and the laypeople who can apply such insights productively in their own lives—there may be even greater risk of getting caught up in the overgeneralization of concepts such as loss aversion in communicating with our clients. On one hand, few of us are experts in these fields ourselves (and even if we were, we likely do not have the time to evaluate and digest the nuances of these fields), which can make us prone to overgeneralize intuitive concepts. But even if we apply the proper nuance (and especially if we don’t), there’s still the risk that our clients may overgeneralize the concepts as they relate to their own situations.

How Can We Better Look At Loss Aversion Going Forward?

From a practical perspective, the biggest insight from Gal and Rucker’s article for financial planners is that we ought to give more attention to gain and loss trade-offs specific to particular situations, because whether we really try to avoid losses (or not) will vary depending on the situation.

Gal and Rucker provide some examples from existing research. For instance, the authors note that prior studies have found that gains may loom larger than losses in the context of mundane goods such as mugs or internet services (once losses/gains are not confounded with action/inaction), whereas losses may loom larger than gains for goods that are harder to replace, such as a town’s mountain view.

Additionally, emotional response to gains and losses may be different in different situations, and behavior may still not indicate relative preferences of gains relative to losses. For instance, Gal and Rucker note that prior studies have found that people complain more about losses than they praise gains, though this behavior does not necessarily indicate that losses actually loom larger than gains. Rather, it may just be that we like to complain when things don’t turn out as we had hoped, regardless of whether losses or gains loomed larger (and therefore it doesn’t necessarily make sense to change our behavior [i.e., act loss averse] just because we complain about losses).

Gal and Rucker also argue that “gain utility”—i.e., the satisfaction derived merely from the act of gaining a good or service—is an underappreciated concept. For instance, an individual may feel more happiness when receiving an item as a gift than they do when finding it on the ground (or vice-versa). A different Gal and Rucker study from 2017 also found that people may receive more satisfaction from finding a lost item (e.g., a lost flashlight) than they do from receiving a new item. And most financial advisors have experienced clients who are so interested in pursuing (i.e., chasing) gains that they will do so without any aversion to the potential losses that may result (despite our warnings!). More generally, the concept of gain utility may also prove to be highly relevant to the different ways in which financial planners package and sell their services in the first place.

Losses And Gains In A Retirement Income Planning Context

Of course, one difficulty of being a practicing financial planner is that we must give advice to clients even when no research exists to provide sufficient insight into specifically how we should apply that concept to a particular topic. We are forced to extrapolate beyond the existing research because our clients need advice now, rather than when researchers get around to investigating these questions!

Acknowledging all of those inherent difficulties, there probably are some insights from the nuance in existing research on loss aversion that we can use to provide better or worse guidance to our clients.

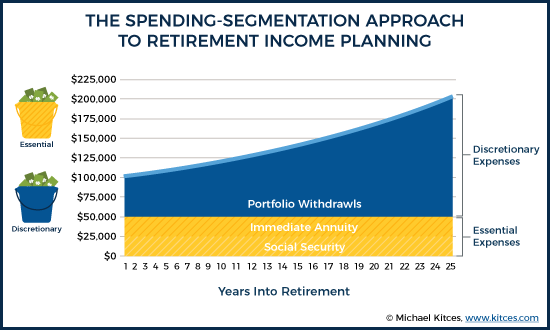

For instance, it is quite possible that the relative importance of retirement income gains and losses differ with respect to the retirement expenses clients mentally associate them with. For instance, with the spending-segmentation approach to retirement income planning (whereby “essential expenses” are covered through annuitization and Social Security while discretionary expenses are covered by portfolio withdrawals), it is quite possible that gains or losses will loom differently based on whether they are associated with essential or discretionary spending buckets.

Similar to how losses may loom larger than gains with respect to an irreplaceable mountain view, it seems reasonable to suspect that losses loom larger than gains when it comes to essential retirement expenses. A $1,000 loss in retirement income that covers essential expenses will almost certainly hurt more than a $1,000 gain towards those same expenses will feel good. It’s likely these most fundamental areas of retirement income where losses may loom larger than gains.

Yet, when looking at one’s discretionary spending bucket, it is not immediately clear whether we should expect people to be loss averse, loss neutral, or even gain seeking. Context is critical here, and the determination will likely vary by individual based on their goals and preferences. In other words, some clients may prefer to take a risk in pursuit of gains and a bigger discretionary lifestyle, while others may not… simply based on their own lifestyle preferences.

For instance, for a retiree who has few hobbies, non-essential financial goals, or other ideas for what to do with extra money, gains in discretionary retirement income could actually induce some stress (though would still almost certainly positive overall). And for a retiree who simply receives little utility (i.e., perceives little benefit) from additional discretionary spending, stability and the perseveration of retirement income they do have may be more important (i.e., losses loom larger than gains).

Yet a retiree who receives more satisfaction from gains in retirement income may be more inclined to be gain seeking, and not be satisfied with simply relying on a guarantee of covering their essential expenses. And this may be true not only for those who already have a lot of wealth and want to upgrade their lifestyle, but may even be true for retirees with little discretionary retirement income to begin with… as the prospects for some meaningful discretionary income may make them gain seeking in this context, even if it means adopting more of a “boom or bust” type strategy that runs the genuine risk of eliminating their discretionary bucket entirely. These types of context-specific planning scenarios warrant even more loss aversion research in the future.

Ultimately, though, the fundamental point is just to acknowledge that there is some good evidence that we have gone too far in accepting the notion that losses always loom larger than gains, and that clients will always want to prioritize avoiding losses over the pursuit of gains. Of course, that does not undermine the importance of the concept of loss aversion itself, which in some situations will be a priority, but it is important to acknowledge the situation-specific dynamics that can help financial advisors give advice that better aligns with fulfilling a client’s goals.

So what do you think? Do you believe the concept of loss aversion has been overgeneralized? Do you see losses always looming larger than gains with your clients? In what areas might gains loom larger than losses? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!

“From a practical perspective, the biggest insight from Gal and Rucker’s article for financial planners is that we ought to give more attention to gain and loss trade-offs specific to particular situations, because whether we really try to avoid losses (or not) will vary depending on the situation”.

Michael, great topic. This paragraph from the article in my opinion sums it up. Generalizations are not effective, with each client comes a level of loss avoidance or potential gain desire.

I appreciate the study because it is important work, with the benefit of experience of multiple down markets I can say that clients fear loss far more than they appreciate gain. That’s a non scientific, 26 years of client experience opinion.

I normally agree with Michael’s well argued articles; however this loss aversion article leaves me far less than convinced.

Very thoughtful, Derek, thank you.

There is no reason to have an aversion to losses, in fact an investor should be prepared to take losses as part of his investment process.

I once head a story that an investment firm in NY that was presenting their process to some Japanese institutional investors. At some point in the presentation, the portfolio manager explained their plan for dealing with losses. The Japanese fellow exclaimed, “You have losses?”

For some, loss aversion is the #1 concern with respect to job security.

Interesting ‘Food for thought’.

My job involves me engaging with Financial Risk takers, traders and asset managers (investors), to discuss this risk processes, and to explore their emotions, sentiments and philosophies connected to their risk processes.

They discuss their view to losses and gains above all else. There is clearly a stronger reaction to losses than gains or higher fear of loss than joy of gain. But context also plays a part, and the balance does chance in different circumstances. – It may be too simplistic to always state loss as loss financial. There is Ego related loss, and social loss. Some people revel in large losses as an ego boost. This may seem counterintuitive, but it plays into their ego,and presenting themselves as ‘Big’ risk-takers. – You would think these people dissappear over time through some ‘darwininan process’. but strangely many keep resurfacing. – Also we see situations where people are comfortable losing, when others lose, and bizarrely can be uncomfortable winning when others lose, a social effect impact.

Clearly there is far more to ‘Loss aversion’ than meets the eye. I think its interesting that people are challening it. I’m still a fan of it, but conscious that a broader relational contect applies.