Executive Summary

Given the inevitability of market downturns over the course of an advisor–client relationship, a key topic for advisors when meeting with new clients is understanding how those clients view risk. Many advisors rely on risk tolerance questionnaires to guide these discussions and inform portfolio construction. However, risk tolerance questionnaires don't necessarily capture the full range of risk dimensions and can sometimes create a false sense of accuracy – which may erode trust if a client reacts differently during a future market decline than their score would suggest.

In this guest post, Meghaan Lurtz, a leading expert on the psychology of financial planning and Professor of Practice at Kansas State University, explores seven dimensions of risk and offers practical questions advisors can use to better understand their clients' perspectives while building stronger relationships that can help those clients weather the next market downturn.

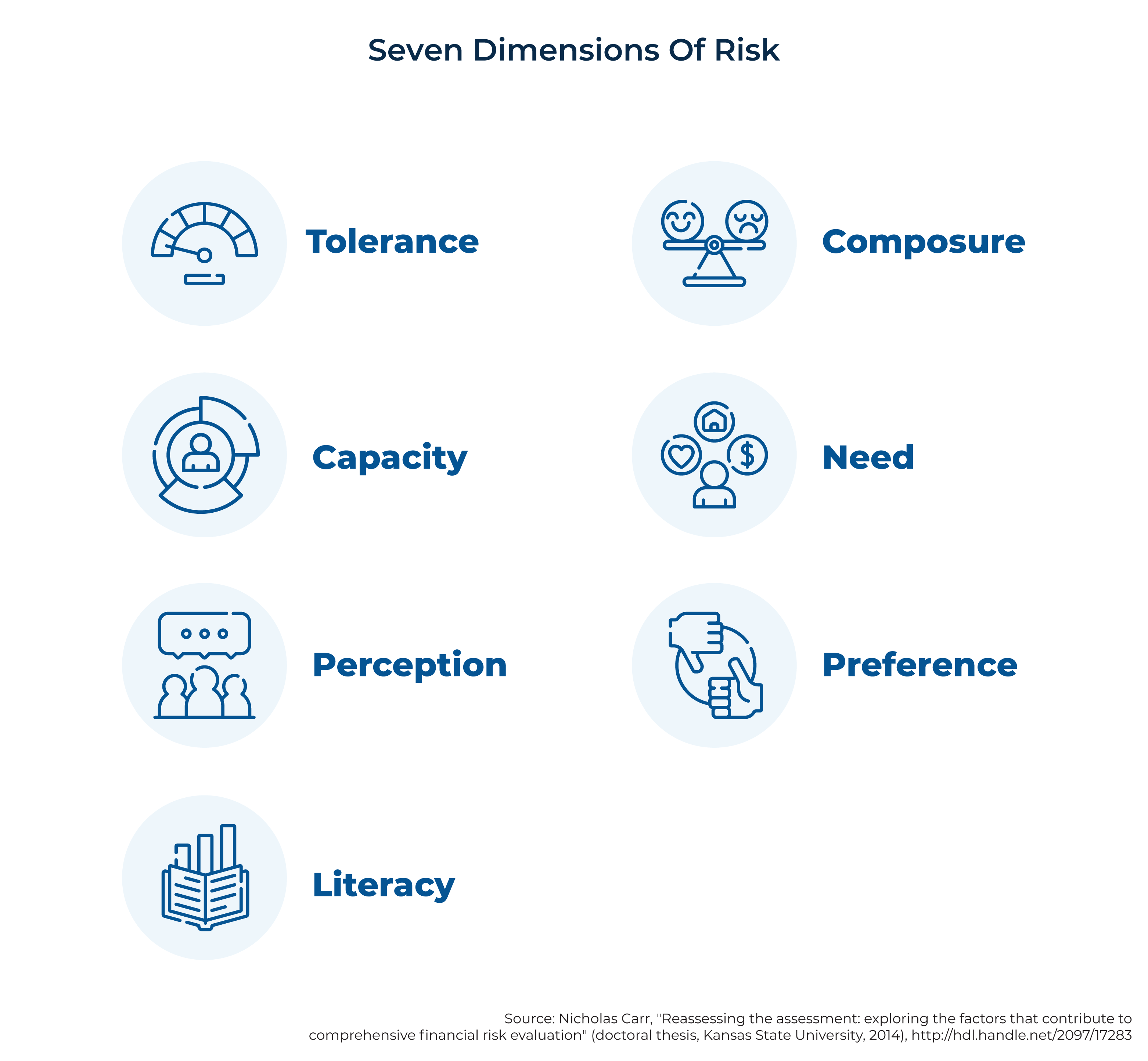

Risk is not necessarily defined in a single dimension. Instead, according to research from Nick Carr, a financial advisor and graduate of Kansas State University's doctoral program in Personal Financial Planning, risk is composed of at least seven interrelated dimensions: tolerance (what an individual thinks they can withstand), capacity (what they can actually afford to lose), perception (how risky something feels right now), literacy (whether they truly understand the nature of the risk being taken), composure (how they behave under stress), need (how much risk is necessary to reach their goals), and preference (the types of risks they are drawn to or avoid). These dimensions often interact in complex ways. For example, a client with a high risk capacity but low composure might agree to a portfolio in calm markets but panic-sell during a downturn.

In addition to understanding where clients might fall along these seven dimensions of risk, meaningful client conversations can help reveal how clients have responded to market volatility in the past – which can be more revealing than a forward-looking questionnaire that asks clients about how they might respond in the future. These structured discussions also help normalize fear, giving clients a framework to recognize and manage emotional reactions when uncertainty strikes.

To help clients articulate their own 'risk story', advisors can ask open-ended questions that reframe the conversation from diagnostic to collaborative. For example, asking "How can I best serve you when things get scary or exciting?" can uncover preferences for communication (such as whether a client prefers an email or phone call), while asking "What feels most uncertain to you right now?" can surface how clients perceive current risks. Notably, these questions can also cover areas beyond market downturns: asking "What's a risk you regret not taking?" can help clients see that avoiding risk can have its own costs.

Ultimately, the key point is that misalignments and illusions of clarity around risk are often best addressed through conversation. And by reframing risk as multidimensional, advisors can move beyond the limitations of a single risk 'score' to gain a more complete understanding of what motivates their clients and how they approach risk – setting the stage for more effective communication and building stronger trust with clients in the long term!

Talking with clients about risk and its troubles is hardly a new challenge for financial advisors. One of the most enduring issues is the misalignment between what clients believe they can handle and what they can actually afford to lose. This often stems from two distinct but related ideas: tolerance and capacity.

Tolerance is subjective (although measurable). It's shaped by a client's emotional response to uncertainty, past experiences, and personality. When a client says, "I can stomach volatility", they are describing tolerance. On the other hand, capacity is objective. It reflects the financial reality of how much risk they can sustain without jeopardizing their goals. A portfolio withdrawal rate, income stability, or insurance coverage all feed into capacity.

Challenges can arise when tolerance and capacity don't match. One client may have ample financial capacity to take on risk but little tolerance. Conversely, a different client with more limited means may have high tolerance, but low capacity to absorb losses without damaging their long-term plan.

Advisors understand these misalignments. They can be frustrating, confusing, and emotional; they make for difficult work when a client's risk score suggests one portfolio, but their behavior in real markets suggests another. Clients may be upset about too much risk that they thought they could handle or upset about not enough risk when they feel they should have been able to beat the market.

For many advisors, risk tolerance questionnaires can seem like useful tools to help make sense of these contradictions. They offer a structured way to start the conversation about risk, but they also imply a level of precision where none truly exists. By producing a neat score or category, they create what some might call an illusion of clarity: the belief that because we have a number, we must also have certainty about what that number means and how to use it. Unfortunately, that's rarely the case.

In practice, markets wobble, and clients often behave in ways that don't match their scores. The mismatch doesn't just frustrate advisors or prompt portfolio changes – it can also damage trust. When clients take action in ways that are inconsistent with their risk tolerance profile, they may begin to question the entire process. They may think, "If my score said I could handle this, why do I feel so uncomfortable?" or "If this is where my advisor said I needed to be, why does this feel so wrong?"

That sense of misdiagnosis can erode clients' confidence – both in their advisor and in themselves. And when trust is shaken, even small market corrections can become major relational ruptures.

Beyond Tolerance And Capacity: Examining Seven Dimensions Of Risk

Before exploring how to address these inevitable ruptures with better risk conversations, it helps to understand the multidimensionality of risk. Nick Carr, a graduate of Kansas State University's doctoral program, studied this concept in depth and found that risk is composed of at least seven interrelated dimensions:

- Tolerance – What an individual thinks they can withstand.

- Capacity – What they can actually afford to lose.

- Perception – How risky something feels right now, often influenced by headlines, peers, or mood.

- Literacy – Whether they truly understand the nature of the risk being taken.

- Composure – How they behave under stress, particularly in real market downturns.

- Need – The extent to which taking risk is necessary to reach the individual's goals.

- Preference – The kinds of risks they are drawn to or avoid.

Each of these dimensions shows up in practice, regardless of whether financial planning standards – or FINRA – require advisors to measure and document them for portfolio construction. For example:

- A client with high capacity but low composure may agree to a portfolio in calm times but panic-sell in a downturn.

- A client with a high preference for entrepreneurial risk (e.g., starting a business) may have a very low tolerance for market volatility – highlighting how some preferences can diverge from traditional investment risk categories.

- A client with low literacy may nod along in meetings without fully understanding downside scenarios, which can later lead to distrust when outcomes differ from expectations.

Carr's framework for the multidimensionality of risk underscores that risk isn't just mathematical – it's also emotional, cognitive, and behavioral. Discussing risk exclusively in terms of numbers – settling for an illusion of clarity – misses the broader human picture and experience of risk. Simplicity, at least when it comes to risk, can create a false sense of security or understanding. That lack of nuance often limits the conversation, the storytelling, and the personalization that are vital for building trust.

Given the complexity of risk, some degree of misalignment and misunderstanding is inevitable. Yet these challenges can be mitigated when risk conversations acknowledge and engage with that complexity. Doing so preserves the storytelling and personalization that help clients feel seen, understood, and supported, even when markets and emotions are anything but simple.

Better Risk Conversations Can Build Trust, Even In Moments Of Misalignment

It can be tempting for advisors to think that their job is to solve risk by eliminating fear. But fear is not a bug to 'cure'; fear is a feature of being human. Daniel Kahneman's research on loss aversion makes clear that the pain of losses is deeply ingrained in how we process uncertainty. Advisors cannot erase that pain with a well-constructed portfolio – and promising to do so with a simple risk tolerance questionnaire only creates false confidence.

Instead, the advisor's role is to normalize fear and prepare for it. By saying, "It's normal to feel anxious when the market falls. Here's how we'll handle that together," advisors validate the client's humanity while reinforcing the strength of the partnership. This reframing shifts the focus from fear avoidance to fear management.

In this sense, risk conversations are less about predicting exact behavior and more about building trust and readiness for the next market swing or life event. Furthermore, as communication experts like Dr. Alison Brooks ("Talk: The Science of Conversation and the Art of Being Ourselves") and Elizabeth Weingarten ("How to Fall in Love with Questions: A New Way to Thrive in Times of Uncertainty") both emphasize, people benefit from having conversations. Dialogue, perspective-taking, listening, and sharing aren't just social niceties we enjoy – they're also how humans help each other feel grounded during difficult times and hard decisions.

Clients who feel understood are more likely to stay the course – not because they have been perfectly typed or measured by some profiling quiz, but because they know they won't face volatility alone. And feeling a little uncomfortable some of the time is normal; it's not a sign of failure.

Risk Is Remembered, Not Reported

Another reason conversations about risk matter is that risk isn't only about imagining the future; it's also deeply rooted in emotionally charged memories. And exploring those memories can help clients understand risk with greater objectivity and confidence.

Yet, many questionnaires ask clients to do the opposite – they ask clients to imagine how they might respond to a 20% market decline. Behavioral research shows that such hypothetical reporting is a weak predictor of real behavior. Timothy Wilson and Daniel Gilbert's work on affective forecasting suggests that people often misjudge how they will feel in the future. Clients may believe they'll be able to 'stay the course', but when they see a six-figure drop in their portfolio value, the experience can feel entirely different. Research in financial planning finds this same nuance: behavior-based (psychometric) measures of risk outperform probability-based (econometric) measures when predicting behavior.

That's why conversations rooted in memory and past behavior during real volatility serve as a far more reliable guide. Advisors who ask about experiences – like the COVID-19 pandemic market crash in March 2020, the Global Financial Crisis in 2008, or even personal events like losing a job – anchor at least part of a risk discussion in lived experience. Questions like, "How did you react the last time the market dropped?" or "What did you learn about yourself during that period?" are powerful because they surface not only behavior but also the emotions and context that shaped it.

Regret is another lens that questionnaires often miss but conversation reveals. A client may not remember a risk score from five years ago, but they will vividly recall the regret of selling too soon – or of missing an opportunity to invest. By asking, "What's a risk you regret not taking?", advisors open a door to understanding a client's motivational drivers. Regret, after all, is one of the most enduring emotions in financial decision-making. As researchers like Neal Roese have suggested, regret can be constructive when it helps people learn and recalibrate. But it can also paralyze. Helping clients reflect on regret through conversation allows them to carry its lessons forward without being defined by it.

Risk Stories Build Resilience

The stories clients tell about their past risk experiences can shape the way they see both the past and future. And remembering what happened – and how it felt – can bridge the gap between reflection and taking action. Conversations like these don't just provide insight; they also build resilience.

When clients talk through fears, missed opportunities, and 'what if' scenarios, they are rehearsing for the future. Think of this in terms of sports psychology and the benefits athletes gain from rehearsing the game, stroke, or routine in their heads. Imagining how one might respond to an event before it happens affects how one actually responds when it does. Advisors can guide clients through structured conversations that normalize fear and provide a playbook for what to do when uncertainty strikes.

Consider the difference between telling a client, "Don't worry, markets recover," versus saying, "Let's imagine a scenario where the market falls 25%. What would you most fear losing? How would you like me to support you in that moment?" The latter approach doesn't erase fear – it validates it. And in doing so, it transforms risk from an external threat into a shared challenge that advisor and client can face together.

This kind of preemptive conversation also helps reduce the sense of shame or failure that clients sometimes feel when they experience fear. A client who has already discussed their likely reactions and agreed on how the advisor will provide support will view anxiety not as a weakness but as an anticipated part of the process. That normalization is critical for maintaining trust during stressful times.

Stories also endure in ways that numbers can't. Once shared, they become our anchors, shaping future behavior more reliably than a score ever could. For clients, these stories become part of their planning narrative; for advisors, they become tools to help normalize fear and maintain trust during stressful times.

When advisors approach risk conversations through storytelling and reflection, the process naturally shifts from categorizing clients to exploring their experiences. That shift has a few key implications for how effective risk discussions are conducted:

- Don't stop at the score. Questionnaire results should serve as a starting point, not a final answer. The more important work happens in the conversation that follows.

- Probe all seven dimensions. Even if Carr's framework isn't formally measured, keeping the categories in mind can help advisors ask questions that reveal perception, composure, or literacy – not just tolerance.

- Name the illusion. Simply telling clients, "This score is a guide, not a crystal ball. What matters more is how we use it as a conversation starter," can reframe expectations.

- Anticipate misalignment. Setting expectations that tolerance and capacity may diverge helps normalize that tension as part of the planning process.

Better Risk Conversations Begin With Better Questions

Understanding risk's complexity is only the first step; the real work happens in the conversations that give that understanding shape, bridging the technical measures of risk and the trust required to act on them. Tools can provide a starting point, but it is dialogue – rich with memory, meaning, and shared preparation – that carries clients through uncertainty.

When advisors lean into conversation, they can shift risk discussions from diagnostic to relational, from hypothetical to remembered, from fear to resilience. That shift not only produces better financial outcomes but also strengthens the advisor–client bond in ways no questionnaire can replicate.

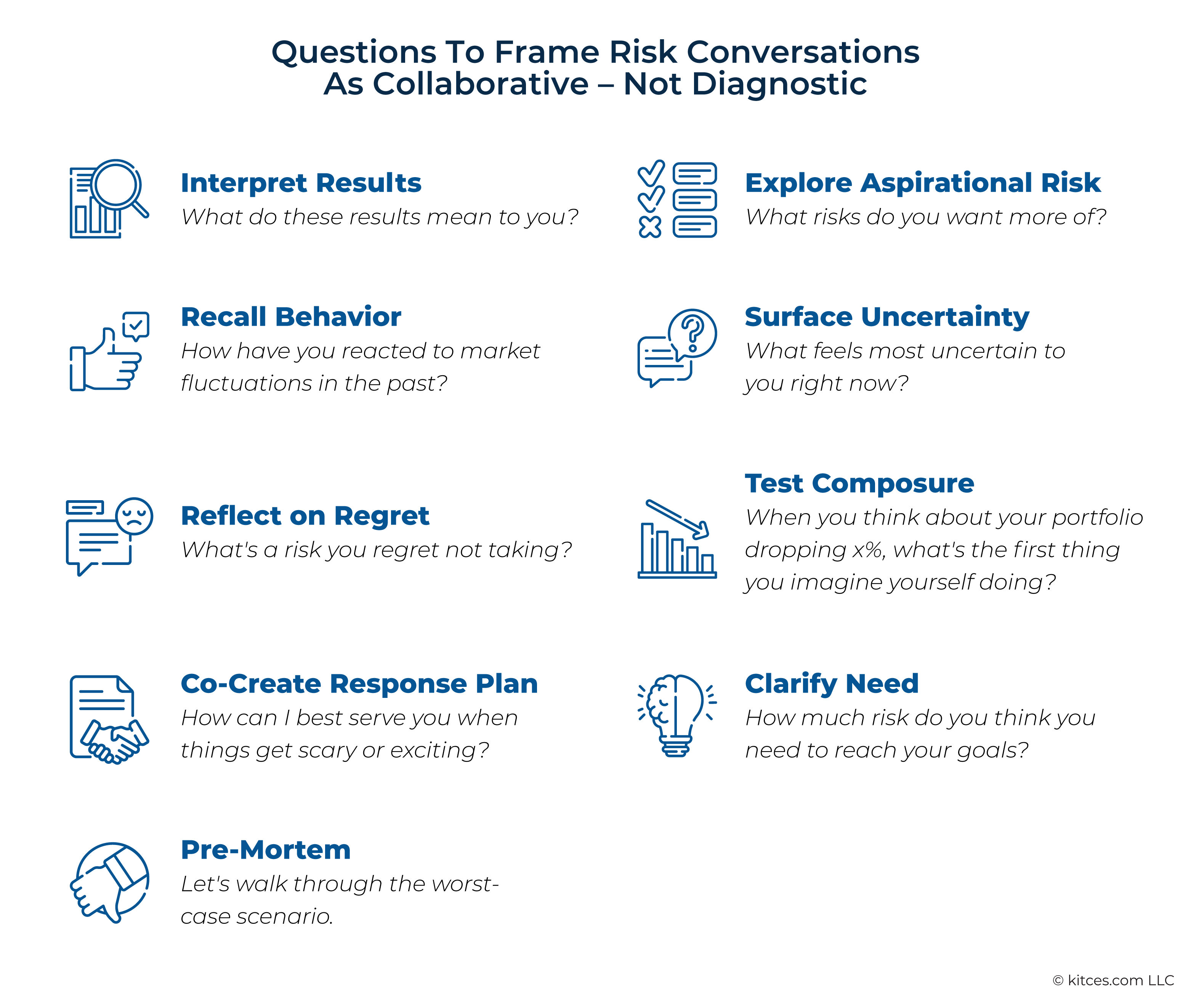

And if risk is a story, not just a score, then advisors need tools to help clients tell that story. The best tools aren't models or charts but questions – invitations for clients to reflect, remember, and plan. Below are practical questions, grounded in research and practice, that can help advisors reframe risk conversations from diagnostic to collaborative.

Question 1. Ask: "What Do These Results Mean To You?"

Most advisors start with a questionnaire, so it's tempting to present the results as definitive. But clients rarely experience it that way. This question flips the script: instead of the advisor explaining what the results mean, the client explains how they interpret – and relate to – them.

Why it matters: This question surfaces context, prior knowledge, and emotions. Some clients may agree with the score; others may resist it. Either response is useful data.

Advisor tip: Listen for language that reveals whether the client is framing risk in terms of fear, opportunity, or obligation. That framing often matters more than the score itself. For example, if the discussion reveals that the client feels high levels of fear and anxiety, make a note in the CRM that this person might need a phone call during the next market turn. If the client is speaking in terms of opportunity, they may need to be occasionally reminded about downside risks.

Question 2. Reflect: "How Have You Reacted In The Past To Market Fluctuation?"

Hypotheticals are unreliable. Memories are less so. Asking clients to recall their behavior during past volatility grounds the risk conversation in lived experience.

Why it matters: Past behavior is a stronger predictor of future behavior than hypothetical scenarios. A client who panic-sold in March 2020 is likely to struggle again unless the advisor builds guardrails.

Advisor tip: Ask follow-up questions about not just what the client did, but how it felt. Did they lose sleep? Did they regret acting (or not acting)? These emotional cues reveal relationships between tolerance and composure. And again, this information can be noted in a CRM, tagging clients who "lost sleep" or "couldn't turn off the news" as those who might need a little extra support.

Question 3. Balance: "What's A Risk You Regret Not Taking?"

Clients often think of risk only in terms of losses. This question reframes it in terms of missed opportunities, helping clients recognize that avoiding risk also carries a cost.

Why it matters: This question surfaces regret aversion, a powerful but often hidden driver of decision-making. Some clients may regret not investing more aggressively early in their careers; others may regret not starting a business or buying a home. By exploring the risks clients wish they'd taken, advisors can uncover how emotion and hindsight influence their current attitudes toward risk. It also helps reveal whether clients tend to overestimate the pain of loss or underestimate the cost of inaction.

Advisor tip: Use this reflection to explore growth opportunities. The point isn't to undo past regret but to learn from it and adjust future behavior. Questions like this can also surface other risk dimensions like perception and preference. For example, a client may not view buying a home as risky even in a difficult market, which is a perception worth exploring. Likewise, some clients may see social risks, such as investing in their friend's business, as more meaningful than purely financial ones. These insights provide valuable context for aligning investment decisions with personal values and life experiences.

Question 4. Prepare: "How Can I Best Serve You When Things Get Scary Or Exciting?"

Volatility isn't only about fear. Markets can also rise quickly, and clients may be tempted to chase returns. This question helps co-create a shared plan for both extremes, anchoring the relationship in proactive communication rather than reactive emotion.

Why it matters: By asking in advance, the advisor builds trust and creates psychological safety. The client feels supported, not judged, when emotions run high. This approach transforms the traditional investment policy statement into something more human – anchored not only in portfolio construction and rebalancing, but in an understanding of how the client wants to be supported when markets move.

Advisor tip: Document each client's preferences. Some may want a call before they reach out; others may prefer a simple email check-in. Revisit these preferences over time, especially after major life events, such as the loss of a spouse or retirement, when emotional needs and communication styles may change.

Question 5. Pre-Mortem Planning: "Let's Walk Through The Worst-Case Scenario."

A pre-mortem is a strategy from behavioral decision-making that asks clients to imagine failure before it happens, then work backward to prevent it.

Why it matters: Anticipating adversity builds resilience. Clients who rehearse how they might respond to a downturn strengthen their ability to stay composed under pressure and are less likely to panic when a downturn does arrive. The process helps them recognize that uncertainty is not a surprise to be feared, but a scenario they've already prepared for. The goal is to make emotional responses feel predictable – and therefore manageable – when volatility arrives.

Advisor tip: Balance realism with reassurance. The aim isn't to scare clients but to prepare them. After outlining the worst-case scenario, emphasize how the plan is built to withstand it. Encourage clients to talk through alternative scenarios – plans B and C – and use reassuring language such as "Life is about pivots… planning is about pivots, my promise to you is to meet and plan with you at each pivot, never hesitate to reach out if something changes or you see a change on the horizon."

Question 6. Reframe: "What Risk Do You Want More Of?"

Most risk conversations focus on reduction: how much loss a client can avoid. This question flips the perspective to explore aspirational risk: the kind that expands possibilities instead of restricting them.

Why it matters: This shift moves the tone from fear to freedom. It invites clients to consider risk not as something to minimize, but as a tool for pursuing what gives life meaning. For some, taking 'more risk' might mean investing in a startup or changing careers; for others, it could mean traveling more or retiring earlier. Exploring positive risk reframes uncertainty as an expression of agency and growth rather than danger.

Advisor tip: Even if these aspirations fall outside traditional portfolio discussions, acknowledging them strengthens the plan's alignment with the client's values. Questions like this surface the why behind the risk; whether it's about protection and stability or creativity and freedom. Advisors who make space for both types of risk help clients connect financial decisions with personal fulfillment, creating plans that feel not only sound but deeply alive.

Question 7. Explore Perception: "What Feels Most Uncertain To You Right Now?"

Risk is not static. A client's perception of risk shifts constantly – with headlines, politics, and personal life changes.

Why it matters: Perception is one of Carr's seven dimensions and often drives short-term anxiety and behavior. A client may be fine financially yet still feel deeply unsettled by inflation, elections, or job security. Helping clients name their uncertainty gives those emotions shape – and gives the advisor something to work with, rather than against.

Advisor tip: Naming the source of uncertainty allows it to be contextualized. Separate the market noise from what truly impacts the plan and normalize how difficult it is to 'set it and forget it' in a world of nonstop news and information. There is so much power in having a simple conversation: research shows that even an eight-minute conversation can change the body's stress chemistry. When risk and anxiety feel like a heavy bucket a client is carrying, the act of talking is like offering to help carry it. The weight is still there, but it is now shared and therefore lighter.

Question 8. Test Composure: "When You Think About Your Portfolio Dropping 20%, What's The First Thing You Imagine Yourself Doing?"

Unlike abstract hypotheticals found in econometric measures of risk, this question pushes for a vivid, behavioral answer – what the client feels and does in that moment of imagined stress

Why it matters: This question surfaces composure, one of Carr's seven dimensions of risk. A client who immediately says, "I'd want to sell," reveals not only what they think they would do, but how they emotionally map their behavior under stress.

Advisor tip: Normalize whatever response the client gives, then work collaboratively to design safeguards – automatic rebalancing, communication check-ins, or agreed-upon 'do nothing' rules. It can be revealing to compare their response with how they behaved in the past. For instance, if they say now that they would sell but previously stayed invested through 2008, invite reflection with a follow-up question about the gap. For instance, "You mentioned you stayed invested before, but now you think you'd sell. What feels different between these moments?" Exploring that gap can uncover emotional triggers and help tailor strategies that anticipate – not just react to – future stress.

Question 9. Clarify Need: "How Much Risk Do You Think You Need To Reach Your Goals?"

Clients often confuse the amount of risk they want to take with the amount they need to take.

Why it matters: This question distinguishes risk need from tolerance. A client may tolerate high risk but need very little, while another may want to avoid risk but require more to meet their goals. Clarifying that distinction grounds the conversation in the plan's purpose, not just the client's comfort level.

- Advisor tip: Use this question to highlight the role of planning as a confidence builder. Advisors might say, "Based on your goals, you actually need less risk than you think", which can be a powerful moment of reassurance. This question can also support client engagement. Advisors don't want clients mentally 'checking out' during a risk conversation, and keeping them engaged helps prevent the illusion of clarity that comes from relying too heavily on a particular model. Real engagement – through conversation, pre-mortems, reflection, and storytelling – keeps the advisor and client connected, even when things get hard.

These questions transform risk from an abstract number into a lived story. Each dimension – tolerance, capacity, perception, literacy, composure, need, and preference — can be surfaced through thoughtful questioning. When advisors make these questions a recurring part of client conversations (and not a one-time exercise), risk becomes less about categorization and more about collaboration. And within that collaboration, trust grows not because clients are fearless, but because they know their fears have been anticipated, normalized, and planned for.

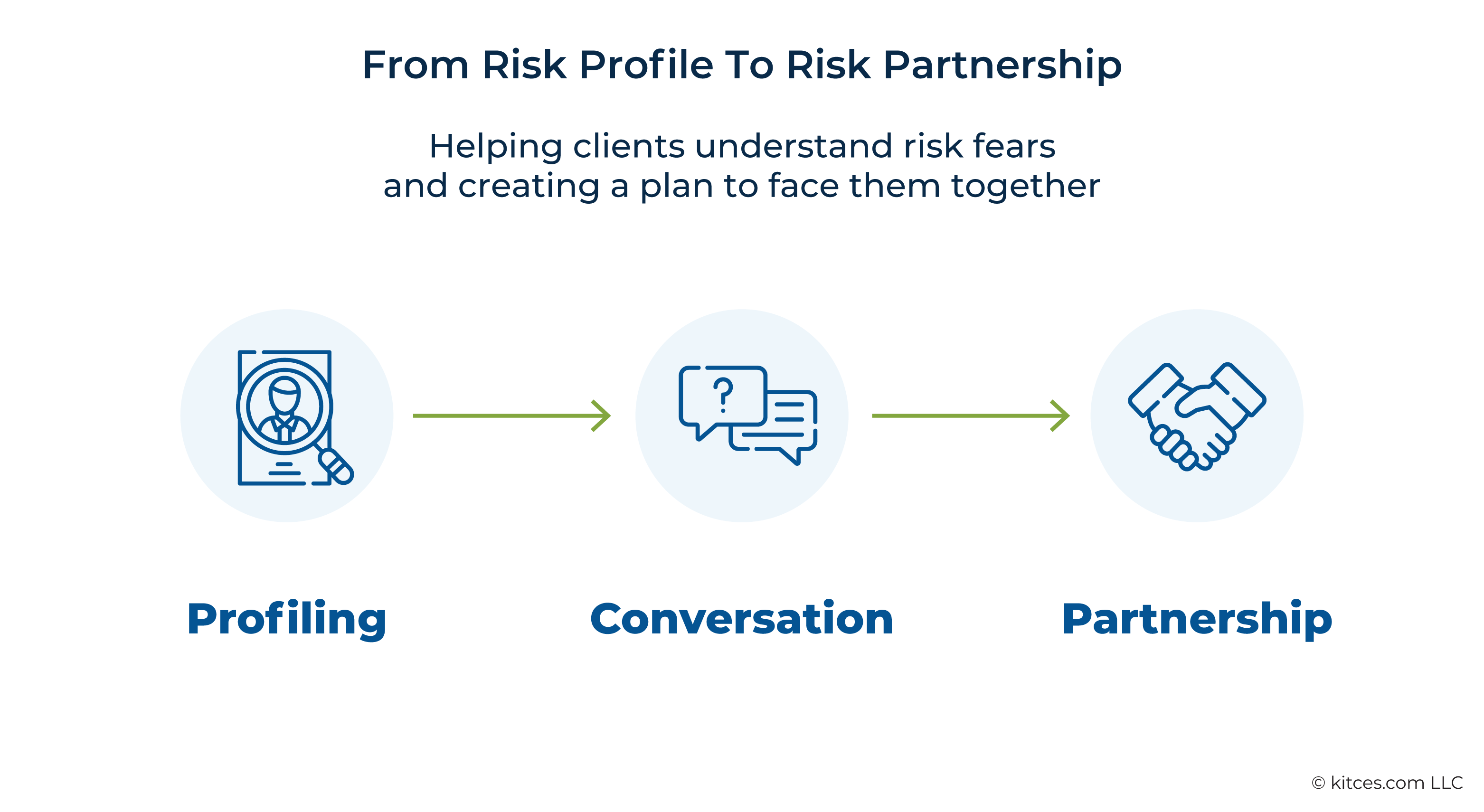

From Risk Profile To Risk Partnership

Risk's misalignments and illusions of clarity aren't solved by sharper questionnaires or more math – they're solved in conversation. By reframing risk as multidimensional, advisors can move beyond the illusion of clarity. Nick Carr's seven dimensions remind us that risk is not a single number but a constellation of tolerance, capacity, perception, literacy, composure, preference, and need. Traditional risk tolerance tools can still serve as useful starting points, but they fall short when treated as definitive. Clients don't live inside scores; they live inside stories – shaped by memories of past downturns, perceptions of present uncertainty, and aspirations for the future.

The practical takeaway is simple but powerful: ask better questions. When advisors invite clients to interpret their results, reflect on past behavior, anticipate future fears, and articulate the risks they want more of – not just less of – they transform risk from a technical exercise into a collaborative narrative. That narrative not only improves portfolio alignment; it also strengthens the advisor–client bond.

Ultimately, the advisor's role is not to make clients fearless, but to normalize fear, prepare for it, and face it together. Numbers may inform portfolio design, but it is stories – and the conversations that elicit them – that sustain trust through volatility. Advisors who move from profiling to partnering, from scoring to storytelling, don't just help clients manage risk. They help them live with it in a way that feels understood, supported, and resilient!