Executive Summary

Welcome to the July 2025 issue of the Latest News in Financial #AdvisorTech – where we look at the big news, announcements, and underlying trends and developments that are emerging in the world of technology solutions for financial advisors!

This month's edition kicks off with the news that CRM provider Wealthbox has sold a majority stake in itself to PE firm Sixth Street, marking a new phase in its growth from having a customer base primarily concentrated among small and midsize RIA firms to an increasing focus on larger enterprise firms – which on the one hand is a necessary step in the growth cycle of a technology startup as its existing users grow larger and much of its untapped market lies among bigger enterprises; but which also raises the questions of what changes it will make to compete with platforms like Salesforce among enterprise firms (e.g., enhancing its customization or workflow capabilities), as well as whether focusing more on larger firms will cause it to lose some of the innovative spark that came from rapidly iterating based on the feedback from individual users (which was part of what helped it grow so popular to begin with)!

From there, the latest highlights also feature a number of other interesting advisor technology announcements, including:

- Envestnet has agreed to a deal to sell the data aggregation provider Yodlee, which Envestnet bought for $590 million in a much-scrutinized deal 10 years ago – which both encapsulates Envestnet's struggles to make its many technology acquisitions add up to more than the sum of their parts (which Envestnet is now starting to undo by divesting from those acquisitions under its new owner Bain Capital) as well as the broader failure of data aggregation to live up to its early promise

- Canadian financial planning software Conquest Planning has raised $80 million as it aims to make inroads into the U.S. market while differentiating on its AI-driven "Strategic Advice Manager" that automatically suggests (and even recommends) planning strategies based on client inputs – which could serve as an interesting test as to whether U.S. advisors will have any interest in AI-embedded financial planning software or whether they see it as encroaching on their own value proposition

- NerdWallet has purchased an RIA to serve clients who find NerdWallet via its trove of personal finance content, while also rolling out an "advisor matching" lead generation program to refer prospects out to other advisors, which both highlights the huge business opportunity in lead generation (in that a platform that can effectively bring in prospective clients can monetize them both by funneling them to its own RIA and by selling them to other advisors), but also raises questions about the conflicts of interest that occur when an advisor matching program matches clients with its own in-house advisors!

Read the analysis about these announcements in this month's column, and a discussion of more trends in advisor technology, including:

- As technology providers are increasingly building or acquiring AI notetaking tools to integrate into their own solutions (often for no extra cost beyond the base subscription for the underlying software), there is becoming less and less need to use a standalone AI notetaker – which means that the existing standalone providers will likely need to find more ways to enhance their value, or face struggles amid the increasing commoditization of AI notetaking

- The proliferation of new AdvisorTech solutions over the years has led many to speculate that the industry is overdue for consolidation or contraction – and yet the more likely scenario is that the pace of growth increases going forward as no-code developing tools lower the barriers to building and releasing software… which on the one hand will make it even more difficult to navigate the software options on the market, but on the other hand will help to better highlight the gaps where existing solutions are failing to serve advisors' needs and increase the overall quality of AdvisorTech going forward!

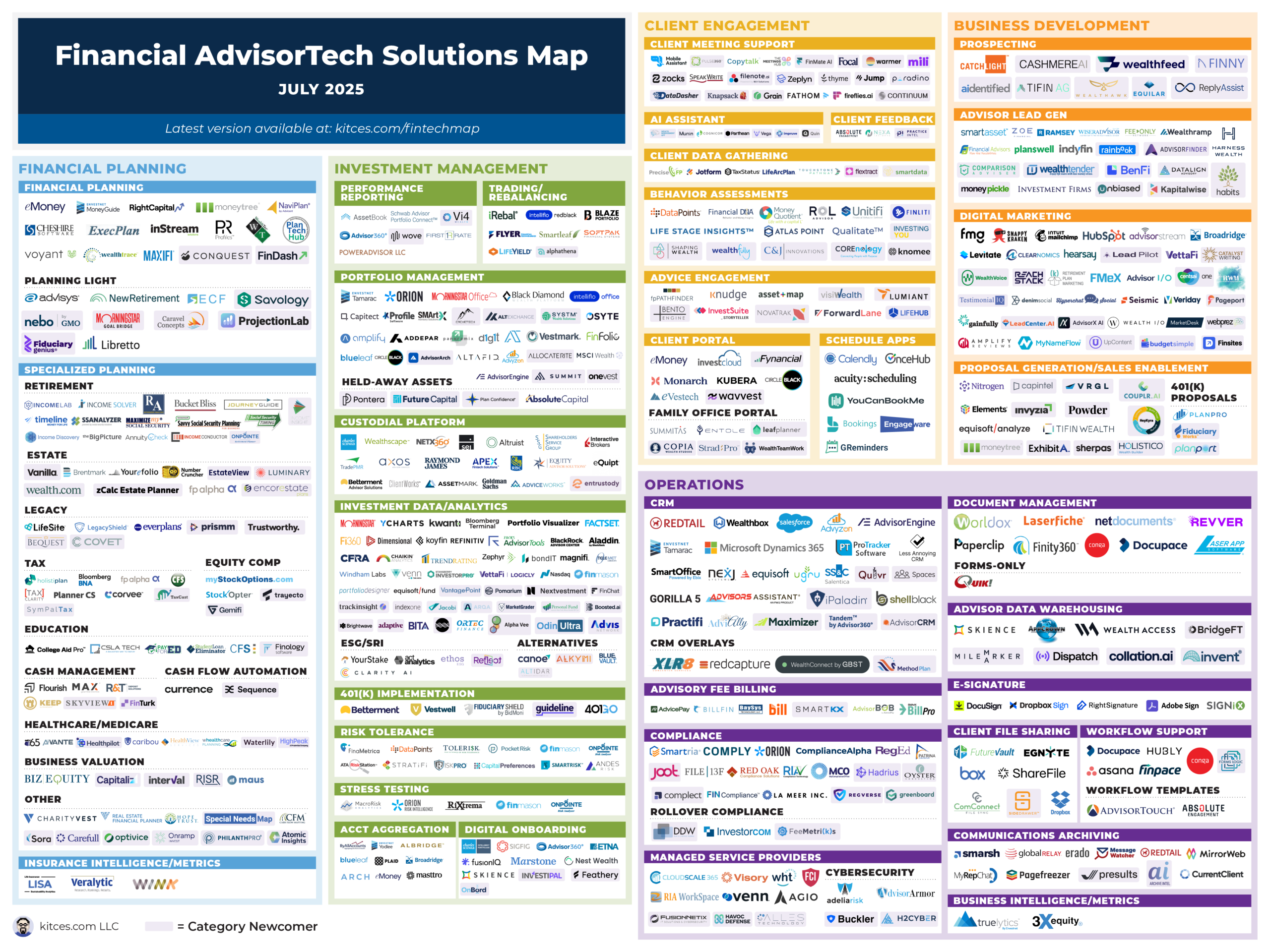

And be certain to read to the end, where we have provided an update to our popular "Financial AdvisorTech Solutions Map" (and also added the changes to our AdvisorTech Directory) as well!

*To submit a request for inclusion or updates on the Financial Advisor FinTech Solutions Map and AdvisorTech Directory, please share information on the solution at the AdvisorTech Map submission form.

Wealthbox Sells A $200M Majority Stake To PE Investors, Accelerating Its Plans To Move Upmarket

There are broadly two ways for a startup B2B technology firm to gain initial adoption. It can start by trying to sell itself to the biggest firms, where landing just a single contract could net it hundreds or thousands of user licenses – which is a slow and significantly risky process (since it often requires working up the chain of decision makers at each firm before receiving final approval), but can prove successful even if just one or two enterprise firms sign on.

Alternatively, the startup can focus on the other end of the spectrum, with the smallest firms in the marketplace. Which makes it easier to sell to each individual firm (since the firm owner, decision maker, and software user are often all the same person), but because each firm may only have one or at most a handful of users, it also often requires selling to many, many individual firms to grow into a sustainable business.

In the AdvisorTech space, two providers have had notable success in using the latter approach of starting with the smallest firms: Wealthbox (with CRM) and RightCapital (with financial planning). The two companies have had remarkably similar trajectories: Both were founded in the mid-2010s (Wealthbox in 2014 and RightCapital in 2015); both sold their software initially to smaller, startup RIAs as affordable solutions that worked well out of the box with a minimum amount of customization required; and both iterated rapidly in their early years to add features and make changes based on user feedback. And just over a decade later, RightCapital and Wealthbox are both among the leaders in their respective software categories in terms of both market share and user satisfaction: In preliminary data from our most recent (soon-to-be-published) 2025 Kitces Research on Advisor Technology, RightCapital ranks second in adoption rate (behind only eMoney) and first in user satisfaction, while Wealthbox rates first in adoption and second in satisfaction (behind only Advyzon), while both hold a dominant market share in their respective categories among the smallest advisory firms where they had made their initial headway into the market.

But at some point, platforms can become so concentrated among small firms that the only path to growth is upwards, to the bigger firms and enterprises that they hadn't previously focused on. And so the big question for providers like Wealthbox and RightCapital that have gained the most traction amid the small firm market is when – and how – to pivot upmarket? Expanding into larger firms requires not just adjustments in marketing tactics to reach a new segment of the market, but also shifts in product development and strategy to cater to the needs of bigger enterprises. Meaning that moving upmarket requires both fresh capital and a new strategic vision to execute on the changes needed to cater to enterprise firms.

Which is what makes it notable that this month Wealthbox announced that it has sold a majority stake in itself to PE firm Sixth Street for $200 million. The deal gives Wealthbox capital to deploy into deepening its enterprise capabilities as well as the ownership of an experienced technology investor that can theoretically guide it in navigating the shift upmarket.

Wealthbox hasn't stated exactly what updates it plans to roll out to better serve enterprise firms, but we can make some inferences by comparing it with Salesforce, which has long held the bulk of market share for CRM platforms among the biggest firms. Much of Wealthbox's early appeal was around its ease of setup and ability to work well out of the box. The tradeoff, however, was that Wealthbox has historically not offered much in the way of customization. In contrast, Salesforce is very customizable to the needs of the firms that use it (to the extent that it requires significant resources to set before firms can even use it for the first time). Likewise, while Wealthbox provides some workflow and reporting capabilities, Salesforce is more robust in both areas. So it stands to reason that at minimum, Wealthbox may be planning to enhance its customization, workflow, and reporting features if it plans to emerge as a viable competitor to Salesforce among enterprise firms.

However, the question going forward (particularly for the smaller advisory firms that make up much of Wealthbox's existing user base) is what might change for them as Wealthbox shifts its focus upstream. There may not be any big changes to the software in the immediate future, but over the long term it's worth wondering if the shift in focus to enterprise firms might make Wealthbox less responsive to the needs of smaller practices than it has been in the past – which by extension could cause it to lose some of the innovative spark that contributed to its current high satisfaction ratings (since in general there's less appetite – or demand – for rapid product iteration among bigger enterprises, where changes need to go through multiple layers of approval before moving forward).

Ultimately, though, the reality is that Wealthbox was never going to stay focused on small firms forever. Even if it wasn't seeking out new enterprise firms to sell to, many of its early existing users, which may have been small when they first started using Wealthbox, have likely grown and matured into medium or larger sized firms by now, meaning that Wealthbox was always going to need to develop its product to meet the needs of bigger firms to keep serving its existing users (while also maintaining its small-firm-friendly innovation to keep bringing in new firms as they enter the market). The challenge for Wealthbox – and similarly positioned technology providers like RightCapital – will be in catering to the needs of an increasingly diverse client base, all while continuing the pace of product improvement that got it to this position to begin with.

Envestnet Sells Yodlee After 10 Years Of Struggling To Capitalize On The Promise Of Account Aggregation And Big Data

About 15 years ago, one of the hottest new innovations in advisor technology was account aggregation, which allows financial data from multiple sources (e.g., client account balances, holdings, and transaction data from multiple custodians, banks, and other financial institutions) to flow into a single, centralized hub in real time. Previously, advisors (and clients or consumers themselves) had needed to log into each individual system to view any client data that was stored in that system, and then aggregate it together themselves in a spreadsheet or financial planning software, but as technology moved from local servers into cloud-based storage, it became increasingly possible for different systems to talk to each other and for account aggregation solutions to use that communication ability to pull client data together into one place.

The promise of account aggregation, and what made it such an exciting development at the time, was twofold. First and most immediately, data aggregation could at least in theory significantly boost advisor efficiency and productivity by eliminating the need to log into multiple systems and manually consolidate client data on a spreadsheet or financial planning software – it could instead be pulled automatically into a centralized dashboard to be viewed all at once (alternatively, data from one source such as the advisor's portfolio management system could be ported over to another source such as their CRM software, eliminating the need to enter data into two separate systems).

But the other tantalizing promise in data aggregation, which seemed to lay just over the horizon, was in making use of the data itself to drive business development. For advisors, this could mean "discovering" clients' held-away assets, which the advisor could then make the case for bringing under their management. For other third-party businesses like portfolio managers and annuity providers, it could mean analyzing client behaviors on the aggregate level, using big data to predict when a particular investment product might be most appealing for a specific type of investor. And so for whoever owned that data, it was possible to monetize it both directly by licensing it to technology providers and financial institutions to make personal financial management tools that made use of the data, and indirectly by selling anonymized data (or insights based on the data) to third parties to use for their own purposes, or even to prompt advisors to find their own ‘next best action' opportunity with their clients based on the data's insights.

Which is why, back in 2015, Envestnet decided to spend $590 million to acquire the data aggregation provider Yodlee. At one level, the acquisition was about tying together the many technology solutions that Envestnet had acquired over the years, including the portfolio reporting/rebalancing/CRM solution Tamarac (acquired in 2012), the robo advisor Upside and the financial planning software FinanceLogix (both acquired in 2015), and later the financial planning software MoneyGuide (acquired in 2019). However, the real angle behind the deal – and the reason Envestnet opted to acquire Yodlee outright rather than simply licensing its data as a Yodlee customer – was about owning the entire trove of data flowing through Yodlee, which in theory could yield insights that could either allow Envestnet to better position its own products or make strategic moves, sell that data to third-party investment managers and other third parties, or use it to help advisors on their platform leverage "big data" to grow their own businesses (and their use of Envestnet's managed money solutions), which would hopefully more than make up for the acquisition cost.

But the deal quickly encountered intense scrutiny from Envestnet shareholders, Wall Street analysts, and industry commentators, to whom Envestnet struggled to coherently justify the immense price it paid for Yodlee. And in subsequent years, that scrutiny proved unfortunately well founded, as Envestnet's big plans to monetize Yodlee's data streams ran into the reality that effectively turning raw data into insights that can be useful for strategic decision making or packaged and sold to third parties is difficult for any technology company (and particularly for a company like Envestnet which had its roots not as a pure technology company but as a marketplace of portfolio management solutions). At the same time, Yodlee's user numbers fell as its technology was leapfrogged by other aggregators like Plaid which could provide more stable data connections with its financial institution sources. The value of its aggregation capabilities also declined as many custodians and technology providers moved away from data aggregation providers altogether in favor of direct API connections with the data sources themselves as regulators increasingly cracked down on the "screen-scraping" practices employed by many aggregators (including Yodlee).

Against this backdrop, then, it's not altogether surprising that Envestnet has announced it will be selling Yodlee to private equity firm STG. The terms of the sale weren't announced, though it is notable that Envestnet had disclosed offers from two prospective buyers in 2024 – neither of which were finalized – which valued Yodlee and Envestnet's broader data analytics unit at just $100 million to $220 million, a far cry from Envestnet's original $590 million purchase price for Yodlee (or the $1.5B+ valuation it would have had if it had merely grown at the overall stock market's rate of return over the past decade).

The sale of Yodlee has seemed almost inevitable since Envestnet's acquisition by Bain Capital last year. In the wake of its 2010s acquisition spree, Envestnet struggled to find a way to make all of its accumulated parts work together – something which the Yodlee acquisition was in part meant to help solve, but which ultimately only contributed to the sense of the whole failing to add up to the sum of its parts. Bain has signaled its intentions to pare back some of Envestnet's "non-core" (i.e., software) divisions to refocus on its core (i.e., asset management marketplace) business, having already shuttered Envestnet's Advisor Credit Exchange earlier this year. And now that the next domino has fallen in Yodlee, it's very conceivable that other technology divisions such as MoneyGuide or Tamarac or more niche products like BillFin could also be on the market sooner or later.

But even if Envestnet's sale of Yodlee wasn't surprising, it's still notable in that it represents just how much the promise of account aggregation has faded in the decade since Yodlee's initial acquisition. From an advisor standpoint, the hassle of frequently broken connections and incomplete data has offset much of the value in time savings that data aggregation had theoretically promised (such that in our upcoming Kitces Research on Advisor Technology, account aggregation tools have the lowest advisor satisfaction rate of any widely-adopted software category). And although account aggregation could occasionally be of use in discovery of clients' held-away assets, the reality is that most advisors who do comprehensive planning are already generally pretty effective at gathering client data and getting a comprehensive view of the client's assets (and clients who don't want their advisor to know about, or manage, certain assets usually won't link those assets to the aggregation platform to begin with). And while many advisors still view account aggregation as having an important role in their business, particularly in areas like portfolio management and fee billing where it's extremely useful to have a real-time feed of the client's account balances and positions wherever they're held, their overall dissatisfaction with the category shows that the aggregation providers that do exist have by and large failed to live up to advisors' high expectations for reliability and accuracy.

More broadly, however, Envestnet's experience with Yodlee goes to show how difficult it is to build "big data" insights that really resonate with financial advisors. For all the cross-selling possibilities that Envestnet's various technology components theoretically enable, the reality is that advisors for the most part just want their technology to do the thing it does, and do it well – not to steer them or their client to another product or solution. And as advisors increasingly focus on comprehensive financial planning, they're already finding those opportunities for themselves using the "small data" of their own client practices and engaging in client conversations, without the need for "big data" insights to guide them there. Yet arguably, Envestnet's woes may actually be simpler: when the core of the business is built around earning basis points on assets, it's hard for SaaS fees to compete, such that Envestnet (or its new owners) may have finally recognized that selling software at SaaS fees on top of an already lucrative basis point-based marketplace business might simply be more trouble than it's worth. Which may actually be good news for users of MoneyGuide and Tamarac, both of which have seen declines in adoption and satisfaction in recent years according to Kitces Research on Advisor Technology – because if they're eventually sold to a new owner that will focus on them (and fully invest resources) as standalone software (rather than as a cross-selling extension of a product marketplace), they may actually see improvements in functionality that can help them better compete with the now-more-popular standalone solutions on the marketplace.

Conquest Planning Raises $80M To Scale Its U.S. Distribution, But Will AI-Enhanced Planning Be Enough To Crack The U.S. Market?

Financial advisors have long sought ways to become more efficient, but not all tools aimed at increasing advisor efficiency have been successful. On the one hand, software that can help reduce time spent on repetitive manual tasks like data entry and creating or updating spreadsheets has proliferated rapidly and become embedded in advisors' tech stacks – think rebalancing tools like iRebal, financial planning platforms like eMoney and RightCapital, or tax planning solutions like Holistiplan. What ties these tools together is that they enable advisors to leverage more of their time for in-depth planning and client conversations, allowing them to do better (if not necessarily faster) planning to enhance their value proposition.

On the other hand, however, tools that have sought to reduce time spent on the planning itself have struggled to gain significant traction among advisors. "Planning lite" tools like Advysis and Boldin (and fuller featured but still "streamlined" financial planning tools like Orion Planning) with the goal of enabling advisors to quickly produce financial plans have historically had low adoption rates. Likewise, the field of robo-advisors-for-advisors, which saw huge inflows of investment dollars in the 2010s on the promise of democratizing financial advice by fully automating the portfolio management process, has mostly collapsed down to a handful of "digital onboarding" tools. In both cases, the selling point of enabling advisors to serve high volumes of clients by cutting down on the time required to serve each client was undermined by the reality that advisors' pain point was never about the amount of time needed to serve each client – it's that the time and cost of acquiring clients is so high that advisors are better off trying to serve a smaller number of clients for a higher fee per client. So instead of solutions to serve more clients cheaply, advisors really want solutions to help them go deeper into planning for the clients they already have (or want to have), which gives tools that free up more time for planning by eliminating manual tasks a higher value proposition than those with the goal of spending less time on planning itself.

All this is one reason that, while AI tools have proliferated within and among the technology that advisors use, AI has so far mostly stayed out of the financial planning software category. Although this is in some part due to fiduciary and liability concerns – since entrusting planning recommendations to a black box AI engine that can't necessarily explain its own methodology introduces serious questions about how advisors can justify or be accountable for AI-generated advice – it also comes down to the reality that many advisors view the process of analyzing the client's financial situation, brainstorming planning ideas, and developing recommendations as part of the value that they bring as (human) financial advisors. If a piece of software came along where advisors could plug in their clients' financial data which the software would process and then spit out a recommendation, advisors might be skeptical that it would really work as a substitute for applying their own expertise to the client's financial situation. Just as they've had little appetite for other tools that sacrifice in-depth planning for the sake of efficiency, they may be disinclined to use a tool that automates what they view as a significant part of the value that they add in the planning process.

In this context, it's notable that this month financial planning software provider Conquest announced an $80 million Series B fundraising round. Although Conquest has had significant adoption in the Canadian market and has been available in the U.S. since 2022 (most notably via a partnership through Pershing X's Wove platform), it so far has yet to gain a significant share in the U.S. market (which is dominated by the three major players of eMoney, RightCapital, and MoneyGuide). This current fundraising round can likely be seen as the start of a new attempt to gain inroads in the U.S. through expanded marketing and distribution efforts.

What's different about Conquest is that it has embraced the application of AI to financial planning rather than shying away from it. Conquest uses an embedded "expert engine" which it brands as its Strategic Advice Manager (SAM), which analyzes a client's financial situation, goals, and preferences, and outputs a list of potential strategies that the advisor can choose to model. It also includes an "auto-planning" feature in which the SAM engine automatically selects the strategies that, by its calculations, would be the best for fulfilling the client's planning goals. In other words, Conquest is actually developing the type of tool that can input client data and output AI-generated planning strategies – which forces the question of how essential advisors see their role in the process of analyzing and developing recommendations.

As previously noted, advisors have historically balked at tools that cut down on time spent planning or conversing with clients, while embracing those that eliminate repetitive manual tasks. And to that end, it's worth asking which side of the divide the process of brainstorming and analyzing potential planning strategies actually sits on. Is it a personalized process that requires a high amount of creativity and applied planning expertise – that is, the kind of task that humans have so far proven far better at AI than carrying out? Or can it really be distilled down to a series of "if-then" statements that, when all the relevant client information is fed into it, will produce a strategy that's at least as good as what the advisor would have come up with themselves? Opinions doubtless vary among advisors, but as the recent history of advisor technology shows, whether Conquest resonates among advisors in the U.S. may come down to whether it positions itself as a way for advisors to "democratize" planning and serve more clients – which has historically struggled to resonate with advisors – or as a way to go deeper into planning by getting manual tasks out of the way of discovering more planning ideas or enabling further analysis and conversational jumping-off points

Regardless of its product and marketing strategy, Conquest will have a hard road ahead in disrupting its deeply entrenched competition, particularly eMoney and RightCapital, which according to Kitces Research on Advisor Technology have maintained both high adoption and high satisfaction among advisors. However, there could be an opening for Conquest to market itself against MoneyGuide, which has been declining in both adoption rate and satisfaction in recent years, and whose user base of predominantly mid- to large-sized RIAs meshes with Conquest's roots in working with Canadian banks and broker-dealers (which employ the vast majority of financial advisors in Canada).

Ultimately, then, it will be interesting to see how Conquest positions itself as it deploys its fresh capital to increase its exposure in the U.S.. If it does turn out that an AI-enhanced version of financial planning software can gain traction among advisors, it wouldn't be surprising to see other providers like eMoney and RightCapital start to roll out their own SAM-like planning engines. If it struggles to find adoption, however, it will most likely be because it strays too close to where advisors see themselves fitting in the planning process, and ultimately detracts (rather than adding to) their value proposition.

NerdWallet Launches A Subscription-Based RIA To Monetize Its Own Non-AUM Advisor Referrals?

One of the biggest challenges of building an advisory firm is not necessarily serving and advising existing clients well, but efficiently acquiring new clients. Many advisors are experts at the former but struggle with (and frankly have limited interest in) the latter, so much so that our Kitces Research on Advisor Marketing finds that client acquisition costs of $3,000–$5,000 per client are very typical. And so rather than try to build a marketing machine on their own, many advisors simply pay lead generation services to do it for them (where at least the relatively high costs are more fixed and known, and can still be cost-effective for the 'right' long-term client). In these cases, the lead generation service does the work of bringing in prospects (e.g., through content generation like SmartAsset or Ramsey's SmartVestor Pro, or advisor matching and rating services like Wealthtender and WiserAdvisor), and delivers those prospects to the advisor for a fee.

Advisor lead generation services can be a very lucrative business, as the lifetime value of an advisory client itself is incredibly high (where a $1M AUM client paying $10,000/year for the next 20+ years is a six-figure lifetime client value!), which means advisors are often willing to pay large amounts – up to and exceeding 25% of the client's lifetime revenue – for prospects whom they can convert to ongoing clients. At the same time, however, it is still a fairly inefficient business: The lead generation services often cast a very wide net to draw in as many prospects as possible, which means that there are a large number of prospects who aren't a good fit for any of the advisors in the service's network (most often because they don't meet the advisors' minimum asset or fee levels). Historically, those ill-fitting prospects were simply a sunk cost for the service – that is, consumers whom the service reached but couldn't monetize in any way. Which still was acceptable to the lead generation services because even if only a small percentage of prospects actually converted to become clients of advisors in the network, those few clients were lucrative enough to make the whole venture profitable. But it still left an opportunity in all those unmatched clients if they could be monetized in some other way.

Recently we saw one version of a lead generation service solving for this issue with Zoe Financial, which debuted a robo-TAMP platform in 2023 designed as a low-cost way for advisory firms to still take on and "serve" lower-AUM clients who otherwise would not have qualified for advisors in Zoe's network (where Zoe's TAMP onboards the clients into the advisory firm's models and AUM fees are split between the two, allowing the advisory firm to earn asset management fees for a marginal cost that is only incurred when revenue has already shown up). It was a clever method of monetizing some portion of the smaller prospects that had found their way to Zoe but would have otherwise been a sunk cost to the platform if they hadn't found an advisor to work with, and it led to an investment of nearly $30 million from several of Zoe's own clients to further bolster its marketing and growth efforts so it could bring in more prospects to monetize either by signing on directly as a "full" client of the advisor or by being served indirectly by Zoe via the TAMP (though still technically being a client of one of the advisory firms on Zoe's network, to whom the TAMP serves as a subadvisor).

And now another advisor lead generation service is trying out another way to monetize prospects who might not be a fit for its advisor network. NerdWallet, which only recently began an advisor matching (i.e., lead generation) service in addition to its core business of matching consumers to credit cards and banking products, announced this month that it had purchased a New York-based RIA to form NerdWallet Wealth Partners. Which, similar to Zoe's strategy, appears to be aimed mainly at ensuring that prospects who search for an advisor on NerdWallet are able to find an advisor who will take them as a (paying) client, whether through an advisor on NerdWallet's network, or at their own in-house RIA that is being built with a subscription fee model to serve ‘HENRY'-style clients with little or no AUM (who wouldn't fit most other traditional advisors).

What's interesting is that, according to NerdWallet's disclosures, it actually provides its advisor matching services through Zoe. In other words, prospects who search for an advisor on NerdWallet are served matches from NerdWallet Wealth Partners (the in-house option) and additional matches via Zoe. If a client signs on with an advisor through Zoe, a portion of Zoe's referral fee (which itself is typically around 25% of the advisor's revenue from the client) is passed on to NerdWallet. So to put it another way, NerdWallet is serving not only as a lead generation service to its own advisory firm, but also to Zoe, with Zoe giving up a cut of its own revenue to outsource lead generation to NerdWallet's well developed content marketing machine.

All of which goes to show just how big the business opportunity is for firms that can actually do lead generation well, to the extent that lead generation services like Zoe are willing to outsource a portion of their own lead generation to providers like NerdWallet (or viewed another way, Zoe as a lead generation service must source its prospects somewhere, and sometimes that might be another media company that has its own goals to be an advisor matching service!). Which is why it makes sense for NerdWallet to also operate its own RIA, since if it's doing well enough at bringing in prospects that other lead generation services are outsourcing their own lead generation to it, then there's likely a business opportunity in owning its own RIA to serve some of those prospects itself (especially the lower-AUM higher-income clients that don't necessarily fit well with traditional AUM-based advisory firms).

The question going forward will be how NerdWallet can navigate its lead generation platform's obvious conflict of interest of having its own RIA being one of the advisors "matched" through the platform. If one company owns both an RIA and a lead generation service, it would naturally be incentivized to refer clients to its own RIA where it can keep 100% of the advisory fee rather than just the portion it receives for referring clients to a third party. Assuming NerdWallet Wealth Partners shows up in every search that a prospect makes, how transparent will NerdWallet be in disclosing how its own financial interests affect its advisor matching results? (The fact that NerdWallet is in the RIA's name at least reasonably ensures that prospects know that the conflict exists, though they won't necessarily know whether NerdWallet is really "best" for them.) Or will NerdWallet try to steer its internal RIA to "just" be the provider of choice for HENRY clients that it couldn't effectively refer out to Zoe advisors anyway?

Ultimately, it's possible that NerdWallet is still figuring out exactly which strategy gains the most traction, and that it won't maintain this conflicted arrangement indefinitely. But it serves to highlight how, once a platform proves successful at drawing in prospective clients, there are multiple ways of trying to monetize that attention, as the greatest cost for most advisory firms is not the operational cost to service clients but the acquisition costs to get them in the first place. In NerdWallet's case, having a media company that already can generate the leads, it now has choices about it will monetize by serving the clients themselves or referring them out to be served by others – though as this case shows, it's hard to do both without introducing conflicts that compromise the trust that's necessary for the lead generation service to gain traction among prospective clients.

AI Notetaker Tools Are Going Native Into Other AdvisorTech Software: Feature Or Standalone Product?

When a company first releases a new and groundbreaking piece of technology, it's easy to think that they'll always have the market for that technology all to themselves. One good example of this from consumer technology is Netflix, which became one of the first providers to offer on-demand streaming of movies and TV in the late 2000s. For a long time, Netflix had little competition in this space, to the extent that it became virtually synonymous with streaming (as evidenced by "Netflix and chill" becoming the go-to euphemism for a casual date night). And yet, the fact that Netflix was one of the first companies to successfully monetize streaming TV didn't mean it had the technology all to itself; gradually, studios and TV networks began introducing their own competing streaming services that served as the exclusive home for those companies' content, forcing Netflix to radically adjust its business model to adapt to the new environment and produce its own exclusive content to keep subscribers on its platform. Today, when consumers decide which of the now dozens of streaming platforms to pay a monthly subscription for, they do so not based on the fact that they offer streaming (because all of them do) – they decide based on the content available on each platform. Or in other words, there's little business opportunity today in "just" being a streaming platform, since streaming technology itself has been commoditized and now serves simply as the medium through which the actual product – the TV or movies living on the platform – is delivered.

A similar story is in the midst of playing out in the world of AI meeting note tools. After generative AI came into the mainstream with the release of ChatGPT in late 2022, one of the first use cases to come to market was tools that could transcribe a meeting recording and, after running the transcript through a Large Language Model (LLM), produce a summary of the meeting's main points and action items. A huge number of these tools subsequently cropped up, with 14 different advisor-specific AI meeting note tools appearing in the "Client Meeting Support" category of the Kitces AdvisorTech Map over the last two-plus years, as the sheer utility of AI notetaking – and the time savings of having an expedited production of meeting summaries, follow-up emails, and meeting-related tasks that only need light editing from the advisor, generated in a fraction of the time a human would need to do the same thing – made a seemingly obvious business case for providers offering that technology.

And yet, the sheer number of different AI notetakers on the market is also evidence that no single provider has a sole claim to AI meeting note technology, as "anyone" can use available LLMs to feed in a meeting recording and generate the subsequent summaries and follow-up emails. Indeed, there are so many AI meeting note providers that new technology companies have sprung up just to serve them, e.g., Recall providing APIs to access all the common virtual meeting tools to generate recordings and transcripts – a quintessential example of the business adage of "selling shovels in a gold rush" (where the people who get rich aren't the ones mining for gold, or in this case selling AI-generated meeting summaries, it's the ones that sell the materials used by the gold miners, or in this case used by the AI startups that need meeting access to generate summaries).

The upshot is that today it's relatively cheap and easy to spin up a basic AI notetaker, leading to a wide range of tools for advisors to use… and to a rapid commoditization of AI meeting note technology. Which means that in addition to the proliferation of standalone AI notetakers, an increasing number of existing technology platforms are offering AI notetaking – not as a separate product, but instead as a feature that's integrated within the rest of their technology and can be offered at little or no additional cost. For instance, CRMs such as Wealthbox and Advisor CRM have each announced their own integrated AI meeting assistants, while the custodian and portfolio technology platform Altruist has acquired the standalone notetaker Thyme to integrate into its platform. In all of these cases, the AI notetakers would be bundled in with the platform's existing subscriptions at no additional cost. Meanwhile, Fireflies, which offers a low-cost general-purpose AI notetaker, has released an advisor-specific version which features integrations with Wealthbox, Redtail, and Salesforce and advisor-specific meeting summary templates at no additional cost beyond the $10–$20/month subscription for its general-purpose notetaker.

The commoditization of AI notetaking has heavy implications for the current crop of advisor-specific notetakers, most of which charge $100+ per month for a standard subscription. With AI notetakers popping up in an increasing number of other platforms, there's becoming less and less reason to buy the meeting summary capability on a standalone basis. Which is pushing some of those standalone providers to find new ways to provide value in ways that aren't as easily commoditized. For example, a number of AI meeting note providers have begun to expand their integration capabilities beyond CRM platforms and into data gathering tools like PreciseFP (which Finmate AI and Zocks have rolled out in recent months) and financial planning platforms like eMoney (announced by Zocks) and RightCapital (announced by Jump), helping advisors solve not just for meeting follow-up work from ongoing review meetings but capturing new client discovery meetings to extract the requisite data for client onboarding and aiming to solve financial planning data entry challenges.

In the end, what's becoming clear is that AI meeting note technology, like video streaming in the Netflix example above, has evolved from being the product being sold to becoming merely a feature that's integrated within the actual product. The open question is where advisors would prefer to see that feature live within their tech stack – while CRM still seems like the most obvious candidate (given its natural role in, literally, capturing the takeaways from meetings to support the ongoing client relationship), Altruist's acquisition of Thyme raises the possibility of AI notetakers existing within portfolio management tools as well. And the continued popularity (for the moment) of standalone tools like Jump, Zocks, and Finmate also raises the possibility that advisors do see room for a new standalone tool in their tech stack, albeit one that includes more productivity tools than just AI notetaking (e.g., the client onboarding and data entry automation made possible by integration with PreciseFP and financial planning tools). The good news for advisors is that it's no longer necessary to pay $100+ per month just for an AI meeting notes tool – the decision going forward will instead be about which platform allows advisors to get the most out of the technology, now that (seemingly) everyone can connect solutions like Recall.io to an LLM and generate meetings summaries in some way or another.

AdvisorTech Providers Will Proliferate, Not Consolidate, As AI-Code And No-Code Lowers The Barriers For Software Development

In the 7 years since we first launched the Kitces AdvisorTech Map, the number of technology providers serving advisors has proliferated (at last count, we're up to 574, from 188 in the first year). And as the Map has gotten more crowded every month, one of the comments that we often hear is the explosion in the number of AdvisorTech providers is itself a sign that the industry is ripe for a pullback – that is, that the total market of financial advisors isn't enough to sustain the number of providers competing for their business, and that we'll inevitably see a slowdown and even a decline in the number of Map entries as companies either consolidate or fold.

This prediction has certainly proven true in some individual Map categories. For example, the former B2B Robo Advisor category used to be full of competitors, but as that side of the industry collapsed amid soaring client acquisition costs and stagnant revenue growth the category dwindled to the point where today it's been consolidated down to a few companies in the Digital Onboarding category. Likewise, the Trading/Rebalancing category has also scaled back significantly as advisors increasingly look to more full-featured portfolio management tools that combine rebalancing, performance reporting, and billing functions rather than standalone rebalancers. But for every category that's in decline, there seem to be multiple others experiencing a surge in growth, with the result being that the overall number of companies on the Map increases nearly constantly from month to month.

Notably, though, the proliferation of companies on the Map is not only a function of how many new companies are being added each month, but the fact that remarkably few ever really go away; instead, most are simply small software companies that may stay small, but have no reason to shut down. Because ultimately, the overwhelming majority (and historically, nearly all) AdvisorTech software solutions are "homegrown" products built by advisors for themselves. Advisor has a problem, can't find software solution, builds own software solution, and then eventually begins selling their internal software solution to their friends and colleagues as a software company on the side was the early-stage growth path for many of today's industry stalwarts (including iRebal, Orion, and Redtail). And in those environments, it's often no more than one to two developers (usually employed directly by the advisory firm early on) to build the software, which is financially supported by the advisory firms' own profits. Once the decision is made to bring them to market for other advisors to use, there needs to be a user interface and ongoing process that works out of the box, which means hiring another developer. Which means there now needs to be more advisors using the software for it to break even, which meant putting some resources into sales and marketing. And then, once a certain number of advisors had started using the software, there needed to be support staff to answer questions.

All-in, it may add up to $500k–$1M of staffing costs… which is not a small amount, but when so much AdvisorTech software costs $49–$99/month, it 'only' takes about 500–1,000 users for the company to be cash flow breakeven. And if the advisor is still using it for themselves, they may even be content to run the company at a slight loss, because that's still less expensive than footing the entire developer bill solely within their own advisory firm. Which means the Kitces AdvisorTech Map is widely populated by a large number of software companies that are operating with a few hundred users but never need to shut down because they're cash flow positive and have particular need to grow further (since they were funded with advisor cash flow and not outside investors)… and then a handful (typically no more than one to three in each category) that evolve the software to enterprise-grade scale and grow to have dominant market share with thousands or tens of thousands of advisor users.

And what's really notable is that, for all the growth in the AdvisorTech space that's happened since we've been tracking it via the Kitces AdvisorTech Map (and accompanying Kitces AdvisorTech Directory), that growth appears poised to balloon even faster going forward.

Because in more recent years, the bar to developing software that not only functions correctly but also makes sense to use has lowered dramatically. Whereas it was once necessary at minimum to have a solid knowledge of Javascript, Python, Ruby, or other coding languages in order to put a working technology product on the web, the rise of "no-code" development platforms such as Bubble, Softr, and Bildr has made it possible for almost anyone to build clean-looking and usable web apps simply by dragging and dropping sections around. Which is now being amplified further by AI-coding tools like Claude Code, Cursor, and Replit, that can generate ‘real' code to build at least simple software apps for those who otherwise have no coding knowledge or experience at all (and can greatly expedite the output of a single experienced developer to build more, go further, and do it faster and thus cheaper).

The upshot, then, is that while in the past there were likely a lot of good homegrown technology solutions that didn't get a wider release because the advisor who created them didn't have the wherewithal to create a version for the marketplace, many more people today can, in the space of a weekend, take a rough idea for software and spin it into a minimum viable product (MVP) ready for beta testing.

And because the bar is lower in terms of resources needed to create and launch a software product, it's also lower for the amount of revenue that's needed to sustain the product. If an advisor decides to release a piece of technology, and their only costs in doing so are $1,000–$2,000/year for the developer platform and $10,000–$20,000 for some ongoing hours of developer time to build and maintain it, then 15–30 licenses at $50–$100/month per seat are really all that's needed to keep the whole thing going.

So to sum it up, more people being able to build and release technology, plus less revenue needed to sustain that technology, equals the potential for many new providers on the AdvisorTech Map, and ones that won't necessarily fold or be consolidated for as long as their creator/owner decides to keep them going (which is often, because most advisors who build software actually need and use it in their own ongoing practices)!

However, while it's arguably a good thing to have more technology choices for advisors to pick from, the downside is that there's a big difference between the type of "minimally viable" app that an advisor could work up in a weekend and the select few that are built to scale at an enterprise level. And a flood of new choices on the market means it becomes even harder for advisors to suss out which solutions can fulfill which functions (never mind which ones actually perform those functions well), especially if a high proportion of them were built quickly and not necessarily meant to support a big user base. Which makes it all the more important to have resources like the Kitces AdvisorTech Map and Directory, and our Kitces Research on Advisor Technology, to help understand which technology advisors actually use (and like), and the rise of more events to showcase emerging technology, such as FutureProof's Demo Drop stage or the XYPN LIVE AdviceTech Competition (which is now accepting applications from new startups through July 10th!).

Ultimately, it's always been the case that whenever there's a gap between what advisors need to better serve their clients and manage their practices and what the market has to offer, a tech-savvy subset will build their own tools to do it how they want it. And an entrepreneurial subset of those advisors will go on to recognize that if they had a pain point that existing software couldn't solve, other advisors must feel the same way, and so they'll build a version to put on the market. The difference going forward is that, with the lower barriers to building and releasing technology, we could see the number of advisors who build their own technology and then actually release their technology grow substantially… and be able to keep their software companies going with remarkably few users to be cash flow breakeven (and thus never need to sell or shut down). Which, while making for a more crowded Kitces AdvisorTech Map, will at least help to highlight where the actual gaps in functionality do exist among major technology providers, and hopefully raise the overall quality of AdvisorTech solutions going forward!

In the meantime, we've rolled out a beta version of our new AdvisorTech Directory, along with making updates to the latest version of our Financial AdvisorTech Solutions Map (produced in collaboration with Craig Iskowitz of Ezra Group)!

So what do you think? Will Wealthbox's planned shift upmarket make it less appealing for its current base of smaller RIAs? Is integrating AI into financial planning software (as Conquest has done) more likely to enhance advisors' ability to go deeper into planning, or diminish their value proposition? Is it worth using a standalone AI notetaker app now that other technology platforms are integrating notetaking tools into their solutions? Let us know your thoughts by sharing in the comments below!

Leave a Reply