Executive Summary

Welcome to the May 2025 issue of the Latest News in Financial #AdvisorTech – where we look at the big news, announcements, and underlying trends and developments that are emerging in the world of technology solutions for financial advisors!

This month's edition kicks off with the news that Altruist has announced a $152 million fundraising round, the latest in a steadily increasing series of capital raises as it has built out new technology features to compete with the "Big Two" custodians of Schwab and Fidelity – leaving the big question of what it intends to do with this fresh round of capital, whether it's implementing (even more) new features, improving its existing product, or acquiring competitors in the ever-competitive race for custodial market share?

From there, the latest highlights also feature a number of other interesting advisor technology announcements, including:

- Charles Schwab has taken a minority stake in estate planning platform Wealth.com as it seeks to offer estate document preparation to its retail investor clients – which on the one hand gives Schwab a value-add that could keep its retail clients from switching to advisors for longer, but on the other hand may not be that much of a value add to begin with since most clients only update their estate documents every 10–15 years

- Flourish has acquired Sora, which helped advisors in aiding their clients in comparing and securing debt from mortgages to student loans to business loans, in the latest sign that the idea of "Liability-Management-as-a-Service", while appealing in theory since most clients hold debt of some kind or another, falls flat in practice since most advisors would rather refer out clients to a third-party loan broker than have in-depth debt planning conversations themselves

- A new startup called Wing is launching a consumer-facing "robo planning" app that provides automated personalized financial planning recommendations based on the user's inputs – but as the original crop of "robo advisors" realized nearly a decade ago, it's hard to profitably serve financial planning clients on a mass-market scale if there's not an efficient way to market to and acquire those clients

Read the analysis about these announcements in this month's column, and a discussion of more trends in advisor technology, including:

- The financial planning platform Libretto has announced a new feature enabling advisors to create "one-click" personalized client letters based on the client's data in the software, representing a potentially valuable use of AI technology that doesn't require the user to master prompting a chat box but instead simply gives them the output they need out of the box

- Amid talk about "agentic AI" tools being the next big AI evolution on the horizon, it's worth reflecting whether agentic AI is really something that advisory firms need, or whether – given the highly process-driven nature of most financial planning business – it's really just better automation and integration features are needed to help make advisors and their teams more efficient

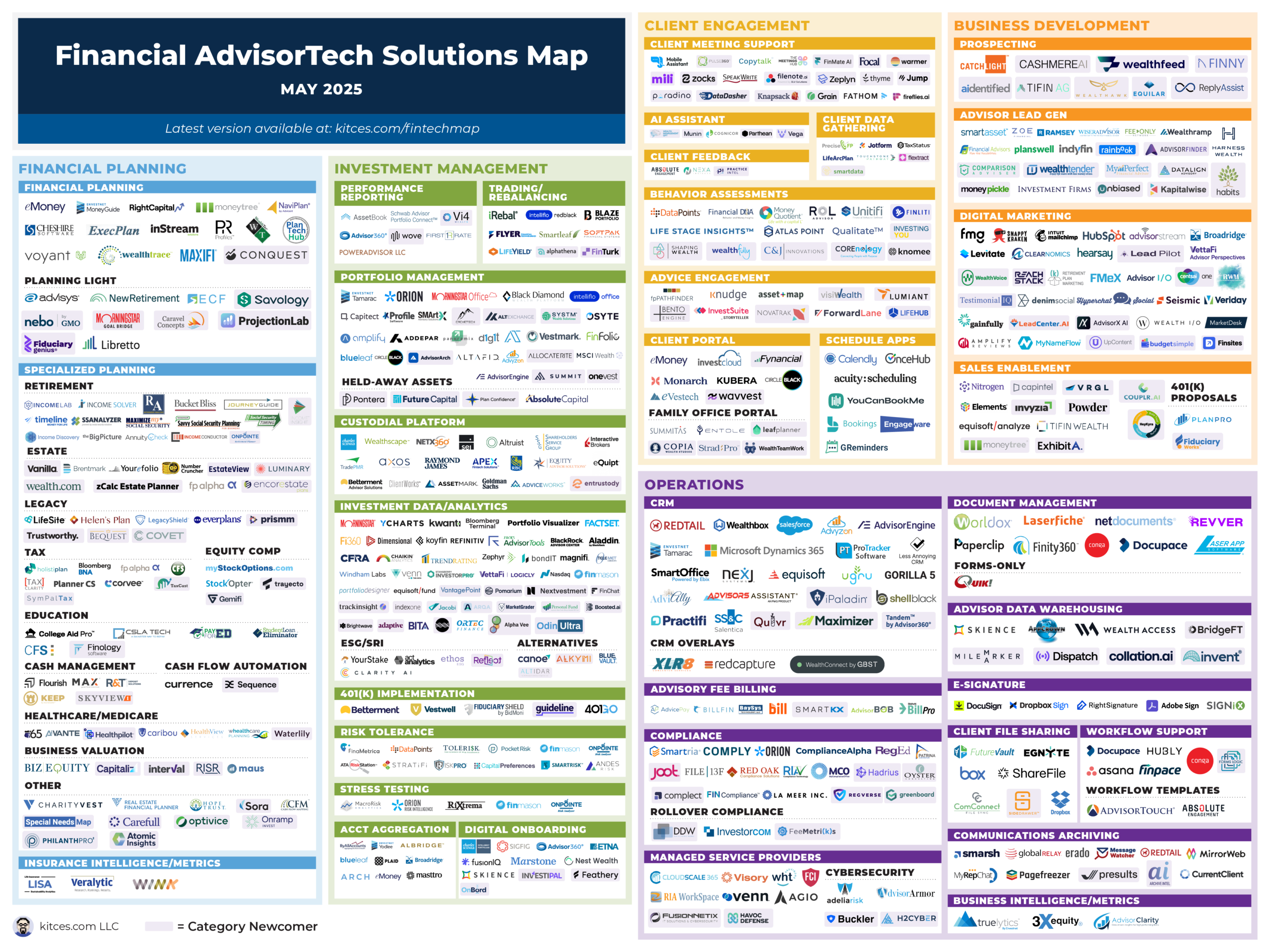

And be certain to read to the end, where we have provided an update to our popular "Financial AdvisorTech Solutions Map" (and also added the changes to our AdvisorTech Directory) as well!

*To submit a request for inclusion or updates on the Financial Advisor FinTech Solutions Map and AdvisorTech Directory, please share information on the solution at the AdvisorTech Map submission form.

Altruist Raises (Another) $152 Million To Compete With the "Big Two" RIA Custodians

For years, the "Big Four" RIA custodial platforms were Charles Schwab, TDAmeritrade, Fidelity, and Pershing. The notable similarity between all four platforms was that they had each arisen out of their respective firms' brokerage arms (retail brokerage in the case of Schwab, TDA, and Fidelity, and clearing for independent broker-dealers in the case of Pershing), and it probably wasn't a coincidence that those four firms in particular grew to dominate the RIA custodial landscape. Because it takes an immense amount of capital to build an RIA custody platform, from the core services of clearing and custody, to recordkeeping and compliance, customer service, building a functional user interface, and marketing to bring advisors onto the platform. But for an already-massive brokerage firm with an existing retail or independent broker-dealer customer base, many of those systems are already in place, meaning that it's just a matter of building out an advisor-facing side that meets the custodial requirements for managing assets on clients' behalf as an RIA. Which isn't nothing, but it certainly is easier than building the entire thing from scratch.

In 2019, a big shift occurred in the RIA custody landscape when Charles Schwab announced that it would be acquiring TDAmeritrade, turning the "Big Four" into the "Big Three". The majority of TDAmeritrade advisors ended up migrating to Schwab in the wake of the merger, but there were still a sizeable number who used the transition as an opportunity to explore alternative custodial options outside of the Big Three. Which opened the door for Altruist, a startup custodian that had only launched just a few months earlier, to start making inroads into the sizeable gap that TDAmeritrade had left in the RIA custodial market.

When Altruist launched, what set it apart was the technology that it offered on top of its custody and clearing functions, including digital account opening (at a time when custodians still often required physical paperwork and 'wet' signatures), robo-like automated rebalancing, and performance reporting functions – all of which had traditionally required spending thousands of dollars to license from third-party technology providers – seamlessly bundled into their custodial platform for 'free' (and able to manage and report on assets at other custodians as well, for a low fee of $1/month/account that was still far less than the cost of most third-party portfolio management technology). In the years since, Altruist has raised steadily increasing amounts of venture capital to fund its operations and invest into further improving the technology that differentiated Altruist from the likes of Schwab and Fidelity: A $50 million Series B round in May 2021; a $110 million Series C round in November 2021; a $112 million Series D round in April 2023; and a $169 million Series E round in May 2024. All of which allowed Altruist to go from starting from scratch in 2019 to being the clear #3 custodian behind Schwab and Fidelity (at least by advisor headcount) by its last fundraising round in 2024.

And now Altruist has kept the funding cycle moving once more, announcing a $152 million Series F round led by GIC, the manager of Singapore's sovereign wealth fund, the proceeds from which Altruist aims to further invest into hiring and product development.

Altruist has deployed its steady stream of venture funds in a variety of ways over the years, from moving from Apex Clearing to its own self-clearing custodial platform to acquiring the competing custodian SSG to building out a cash management account for clients, automated tax-loss harvesting, and a digital bond trading platform. And so it seems likely that new features and/or acquisitions will follow this round of fundraising as well.

To that end, the main question going forward is: What features are left to add that Altruist hasn't introduced already? If you made a list of all the features an advisor would want from their portfolio management technology, trading and rebalancing would probably be at the top, followed in some order by performance reporting, account opening, billing, and possibly a platform for outsourcing model portfolio creation. Altruist already has all of these functions, plus more niche features like cash management and bond trading.

However, Altruist's growth thus far has been driven heavily by its ability to attract newer RIA firms (either starting from scratch, or breaking away from an independent broker-dealer and needing to hang a new shingle), a space where it has been highly competitive (thanks to its tech and ability to save new advisors on third-party tech costs) and benefitted by the fact that many of its competitors have asset minimums for firms to join. Yet the bulk of RIA assets is still concentrated in larger firms, where Altruist does not yet appear to have gained as much traction (and where it's much harder to convince firms with existing clientele at other custodians to move and repaper accounts).

As a result, it seems likely that Altruist's capital focus from here will go towards expanding beyond its core portfolio management functions, and into directions that would increase its appeal to larger RIAs in particular. This might include delving deeper into CRM systems (either by building an in-house CRM, a category that has started to see more disruption over the last year, or building more deeply to Salesforce as the CRM that currently dominates amongst large RIAs), or to further improve on its workflow automation capabilities to help advisors improve the way they use the various parts of the platform (a domain that is especially conducive to leveraging emerging AI capabilities). Or alternatively, Altruist could use the funds to acquire another competitor as it did with SSG in 2023, giving it a boost in market share to leave it better positioned to compete with Schwab and Fidelity, though arguably there are few ‘independent' custodians for independent RIAs remaining that would have a synergistic fit for Altruist.

In the end, while it remains to be seen what exactly Altruist will do to deploy its fresh round of capital, what's clear is that the strategy remains what it was in the beginning: to outcompete other RIA custodians by investing more into technology improvements and creating a more seamless custody-plus-portfolio management experience for advisors. Which is likely what it takes for a firm that hopes to contend with the likes of Schwab and Fidelity (and their incumbent advantages of size and scale), especially as Altruist seeks to continue moving beyond ‘just' smaller RIAs and into the hyper-competitive domain of mega-RIAs where industry consolidation has increasingly concentrated RIA assets.

Schwab Takes A Minority Stake In Wealth.Com To Scale Estate Planning For Its Mass-Affluent Retail Clients

Estate planning can entail different things when going up and down the spectrum of assets and net worth. For high-net-worth and ultra-high-net-worth clients, estate plans often intertwine the twin goals of distributing assets the way that the client wants to and minimizing Federal and/or state estate taxes, which often entails complex trust-based plans to not only remove assets from the client's taxable estate but also set rules for when and how assets can be distributed to various beneficiaries – many of which can get rather complicated when the client wants to avoid having their entire estate distributed to their beneficiaries at once.

Going lower on the net worth spectrum, there's still a need for estate planning, but the degree of complexity needed for "mass affluent" and lower net-worth clients' estate plans is usually less than it is for HNW and UHNW clients. For many of those cases, the client's estate doesn't reach the level that exceeds their state's estate tax threshold (which ranges from $1 million to over $13 million in states that have estate taxes), much less the Federal estate tax threshold (which currently sits at $13.99 million per individual), which removes estate tax minimization as an estate planning consideration. However, those clients do still need to have some estate documents to, at a minimum, ensure that their assets pass according to their wishes and not via state intestacy laws, and sometimes to achieve other goals like designating a guardian for minor children, providing a health care directive to appoint an agent to make medical decisions on the client's behalf if they become incapacitated, or provide for beneficiaries who are disabled.

For the more complex needs of HNW and UHNW clients, estate planning is still often a high-touch service, with financial advisors and estate attorneys often working in tandem to ensure that the client's documents are properly drafted to align with their goals. However, when the client 'only' needs a simple will and health care directive, or a revocable trust to avoid probate, hiring an attorney to draft the documents can feel like overkill, and can often be cost-prohibitive enough to keep the client from taking action to get the estate documents that they need.

In recent years, as the ranks of mass-affluent have grown following a long bull market in U.S. equities, a number of technology startups have arisen to serve the needs of those clients who need estate planning documents, but who don't necessarily need to go to the trouble and expense of hiring an attorney to draft them. Services like Trust & Will, Wealth.com, Vanilla, and EncorEstate Plans have all come about with the goal of helping financial advisors scale the process of providing estate documents to their clients, backed by tens of millions of dollars in venture capital betting that advisors will see estate document preparation as an attractive value-add and flock to implement it for their clients.

In that context, it's notable that Charles Schwab has announced a deal to take a minority stake in Wealth.com, with the explicit goal of building out Schwab's own trust and estate planning services for its retail clients. Specifically, Schwab's intention appears to be to give retail clients the ability to create their own self-directed estate documents, powered by Wealth.com's technology.

The deal has the possibility to rankle some advisors who see Schwab's planned offering as further evidence of Schwab's retail brokerage arm competing against the many advisors who use its RIA custody arm for the same clients. "Mass-affluent" is a segment of clients targeted by many financial advisors, and estate planning is an example of a type of service offered by financial advisors that may convince a retail brokerage client to switch over once their financial complexity reaches the level where they don't want to handle it on their own anymore, and so when a retail brokerage starts offering estate planning services to its mass-affluent customers, that gives them one less reason and pushes out the timeline to when they might want to hire an advisor. And although there's little evidence of Schwab actively trying to break clients away from RIAs on its brokerage platform, there is at least some evidence that retail brokerages like Schwab are eating into independent RIAs' organic growth rates as they seek to offer more of the same services to retail investors that advisors offer to their clients.

But the question is whether or not estate document preparation really provides enough of a value-add to draw clients to Schwab who might have otherwise hired an advisor. The value of estate document preparation has long been a question as it relates to how financial advisors themselves use platforms like Wealth.com – because while all clients clearly need estate documents at some point, the reality is that they usually only need to be updated once every 10-15 years, meaning that at most only 5%-10% of an advisor's clients might actually make use of the service in any given year, making it hard to justify paying for a tool that will only be used for a small segment of the advisor's clients at any time. The fact that Wealth.com has signed on to offer estate document preparation for Schwab's retail clients (as Vanilla similarly did for Vanguard last year) may indeed reflect that it has struggled to gain widespread adoption among independent advisors, who don't see the value added as justifying the cost of another technology tool – and by that logic, Schwab's intention to deploy Wealth.com for its own retail clients doesn't really entail a significant threat to financial advisors, given that advisors themselves largely have opted not to offer that service themselves.

Still, Schwab's investment in Wealth.com is an indicator that there really must be a large number of mass-affluent investors on the Schwab retail platform, to the extent that Schwab is investing significantly in technology to offer them estate planning services at scale in the hopes of keeping them on the platform. The question for advisors is how many of those clients are DIY customers who aren't likely to ever hire a financial advisor, and how many could be convinced to switch over once their finances hit a certain level of complexity – and whether using a tool like Wealth.com to provide estate documents would even make sense at this point as a value add to convince those clients to sign up, given that they'll be able to use it themselves on Schwab's platform anyway?

Flourish Acquires Sora As "Liability-Management-As-A-Service" Falls Flat With Advisors

One of the common themes that comes up in financial advisory industry research that the amount of time advisors spend on a particular activity tends to be closely correlated with how directly that activity impacts the advisor's bottom line. For example, in the most recent Kitces Research on the Financial Planning Process, the three topics that were most commonly covered in clients' financial plans were retirement, investments, and tax planning. In a business model where most advisors are paid based on assets under management, it makes sense that they would be highly focused on investments, while retirement and tax planning represent two of the top concerns of the type of high-net worth clients who tend to hire financial advisors, making those topics nearly as central to advisors' business model as the investments themselves.

This theme also extends to the technology that advisors use. In the most recent Kitces Research on Advisor Technology, the most used technology solutions by far (aside from operational tools like CRMs, website platforms, and scheduling tools) were comprehensive financial planning software (which is usually centered around retirement planning projections) and portfolio management-related tools. Meanwhile, more specialized planning tools, which are designed to go deeper into individual topics that aren't normally covered by standard comprehensive financial planning software (e.g., estate planning, education and student loan planning, equity compensation planning, and healthcare planning), often find much more limited adoption. Which isn't necessarily because most advisors don't do any planning in those topics – they just don't usually impact a significant enough amount of most advisors' clientele (and therefore aren't central enough to the advisors' business model) to justify buying a technology solution to facilitate deeper planning in those areas.

One area of advisor technology where this story has played out in recent years has been liability planning. Debt is no doubt an important area of clients' financial lives, with most clients of financial advisors likely having at least a mortgage, and perhaps other types of debt such as student loans, auto loans, Home Equity Lines of Credit (HELOCs), business loans, and securities-backed loans. That insight led to the launch of solutions like Advisor Credit Exchange (backed by Envestnet) and Sora Finance, both of which aimed to help advisors "manage" client debt by helping clients compare lenders to find the best rate on new or refinanced debt and facilitating the process of applying for and procuring loans.

The issue that both platforms ran into, however, was that while many advisors may be willing to discuss liability planning with clients at a high level, and can often refer clients to a broker who can work with the client to go into the specifics and secure the loan they need, advisors' willingness to step into the process of applying for and procuring loans for their clients themselves is often much more limited. Because for most advisors, loan planning isn't central enough to their business model (because they aren't compensated directly for the loans themselves – which would be a conflict of interest – and there generally aren't enough clients needing new or refinanced debt at any given time to make it a significant part of the advisor's value proposition) to justify using a tool that allows advisors to have deeper conversations about liability planning that they aren't ultimately being compensated for. In January 2025, Advisor Credit Exchange announced that it was shutting down, being in part a casualty of Envestnet's acquisition by Bain Capital but also a reflection of the reality that simply too few advisors were making use of its lending solutions.

And now this month Sora, another of the prominent providers of "Liability-Management-as-a-Service", has announced that it is being acquired by Flourish. Sora will eventually be integrated into Flourish's platform to sit alongside Flourish's cash and annuities products as Flourish continues to build out options for advisors to manage the non-portfolio areas of clients' balance sheets.

It's an interesting acquisition for Flourish, which has found previous success in building an advisor-specific cash management product with competitive interest rates and higher FDIC coverage than standard high-yield bank accounts, and later built out an annuity platform for fee-based advisors. What's allowed Flourish to succeed in those areas has been its ability to offer good rates on cash and annuities through its partnerships with banks and insurance companies. Similarly, the key to this deal would seem to be whether Flourish could actually offer better rates on loans procured through its platform than what clients would be able to find from retail lenders. Because while most advisors may not be willing to get very involved in loan planning for their clients, they might be more inclined to do so when they can demonstrate their value to their clients by getting better rates on debt than the client can find elsewhere. In other words, if Flourish can further leverage its banking relationships to offer better rates on loans through Sora's platform, it could potentially gain some of the traction that Sora wasn't able to achieve on its own.

For Sora, however, the reason for the deal may have been that it simply had difficulty gaining a critical mass of advisor users as a standalone liability planning solution. Because at the end of the day, few advisors see liability planning as central to their business model (aside from some who go deep into student loan planning, for which other specialized tools like Student Loan Eliminator and Finology are available). And for advisors who do get involved with their clients' loan planning, trying to procure and implement the loans opens the door to questions from the client about specific loan products that the advisor might not be able to answer themselves. All of which makes it usually more preferable for advisors to refer both loan planning and implementation out to a third-party broker rather than handling it themselves, even with the help of a technology platform.

And so the question for Flourish going forward as it integrates Sora into its platform will be whether it can get good enough rates on its debt products to make it worth the trouble for advisors to get involved in liability planning. Because while advisors may be eager for tools that can help them demonstrate their value, it's much more enticing when they can flat-out get a better deal on a loan for their clients than it is when the software merely opens the door to a deeper conversation on a topic that the advisor doesn't want to (and doesn't get paid to) go deeper into.

Wing Launches A "Robo-Planning" App For Automated Financial Advice, But Is It Doomed To Re-Learn The Lessons Of The Original Robo Advisors?

The early 2010s saw the launch in rapid succession of a crop of so-called "robo advisors" like Betterment and Wealthfront that employed algorithmically driven investment management technology to automatically invest and rebalance clients' portfolios. The sales pitch for robo advisors at the time was that they would disrupt the financial advice industry by giving anyone access to a professionally-managed portfolio for an annual fee of around 0.25% of AUM, i.e., only about a quarter of the 1% AUM fee charged by most human financial advisors. The early days of the robo advisor era caused some initial concern about human advisors being under threat from the new robo upstarts, but as it turned out, robos were never truly a threat to human financial advisors because clients hire human advisors for more than just managing their portfolios: They hire advisors for the personalized, individual advice they give, and the relationship they build with an advisor who deeply understands their needs and circumstances, which robo advisors were never prepared (and simply never built) to provide.

And so as the 2010s went on, robo advisors not only didn't replace human advisors, but they in fact struggled to gain adoption as high client acquisition costs (that advisory firms have struggled with since long before robo-advisors), coupled with fierce competition between a host of robo advisor platforms led to plummeting growth rates, resulted in a wave of contraction as platforms like Jemstep, FutureAdvisor, and Vanare were either acquired or simply shut down in the face of soaring client acquisition costs. Because as many advisors had learned before, it's extremely difficult to profitably serve clients at a mass-market scale – not necessarily because of the ongoing operational cost of servicing mass-market clients (which was what robo advisors specialized in), but because the cost of marketing to and acquiring those clients (which according to Kitces Research on Advisor Marketing is typically $3,000+ per client household, and higher for high-dollar clients) often breaks the business model before the robo advisor can gain enough users to break even.

Which means that ironically, the technology that initially promised to disrupt financial advisors now largely serves to assist them, as many advisors have adopted various forms of automated portfolio rebalancing in their own portfolio management technology, which in turn allows them to reduce their time spent on investment management tasks and spend more time going deeper into financial advice to provide more value for their clients. In other words, the technology that was supposed to disrupt financial advisors ended up being the technology that advisors used to enrich their own value propositions to clients.

All of which makes it interesting to see the recent news about the launch of Wing, a direct-to-consumer platform which could probably be best described as a "robo planning" app. After asking clients a series of questions about their goals and financial situation, Wing uses its AI engine to generate a "micro plan", along with a portfolio recommendation designed to achieve those goals. The subscription-based app updates the plan continually to adjust for the client's changing circumstances over time.

It's hard to read about Wing and not be reminded of the early promises of the first wave of robo advisors to disrupt the financial advisor model by bringing portfolio management to the masses. Except instead of leading with portfolio management, Wing is leading with financial planning while criticizing the "status quo" of 65-page static financial plans with one-size-fits-all recommendations (although it's worth noting that the "status quo" has already been on the decline for several years, with the most recent 2024 Kitces Research on the Financial Planning Process showing that far more advisors now use a "collaborative" approach to planning that takes the clients' concerns and feedback into account and only a minority of advisors even still use the traditional printed-out comprehensive plan).

But just as the original robo advisors didn't disrupt the human advice model because they lacked the personal advice element that is the real reason that clients hire financial advisors, there's a critical element of conversation and human-to-human relationship missing with Wing compared with the experience of a human advisor. In other words, Wing's ability to take client-entered data and convert it into financial planning insights means that it has simply replicated the role of financial planning software. But even the best financial planning software requires an advisor to interpret and contextualize its output for the client, and a conversation about what the results mean to the client and what (if any) strategy it makes sense to implement going forward. So while the financial planning software can help with the financial planning, the actual financial advice is what takes place outside of the software, and is what separates the experience of a human advisor from an app like Wing that simply takes in client inputs and spits out a list of recommendations.

And just as robo advisors largely took an "if you build it, they will come" approach by assuming that clients would flock to an automated solution that "democratized" investment management with low fees and investment minimums, Wing also seems to assume that offering an automated, low-cost financial planning tool will open them up to a mass market of clients who can't currently afford a human financial advisor but would eagerly pay for a lower-cost solution. Except that offering what substantively amounts to financial planning software directly to consumers is effectively a solution targeted at Do-It-Yourself (DIY) consumers, who are notoriously stingy about spending money for either financial planning or portfolio management (as contrasted with the clients financial advisors serve, who are more commonly delegators and are willing to pay more precisely because they don't want to have to learn the information and manage technology tools themselves to find these answers).

Which means that Wing may soon find – just like the robo advisors before it – that it isn't ongoing operational costs that are keeping advisors from serving those clients, but marketing and client acquisition costs to convince DIY consumers to actually be willing to spend money on their services (despite being DIY). And if Wing can't find a way to efficiently distribute to DIY users who will sign up for an ongoing membership, it may find itself re-learning the all the lessons that robo advisors did (with largely disastrous results) over a decade ago?

Libretto Launches One-Click Personalized Client Letters To Help Advisors Use AI Without Becoming Prompting Experts

One of the earliest (and still among the best) uses for financial advisors of Large Language Models (LLMs) like ChatGPT was as a writing aid to help with client communication. For advisors with limited time or skills in writing emails or newsletters, it was all of a sudden possible to write a brief prompt (like "please write a 250-word explanation of backdoor Roth conversions) and instantly have a block of text that the advisor could then review for accuracy, edit to match their own personal style, and send to the client, all in a fraction of the time it would have taken to write the whole thing from scratch.

The caveat, though, is that LLM prompting is itself a skill that takes time to learn. A basic prompt may get 50% or more of the way to the finished product, but if an advisor wants to get much more efficient than that at creating LLM-generated communications, they need to know what combination of words to put into the platform to get the output that's closest to what the advisor wants. The more complicated the request, the more the advisor might need to hone their prompt to get what they need – and when the communication involves client-specific information, the advisor also needs to take care that they don't inadvertently include private information that gets ingested into the LLM's model (although some tools, like ChatGPT's Pro tier, allow users to specify that information entered into the tool won't be used to train the LLM).

In a way, a basic chatbot-style LLM tool is a little like an Excel spreadsheet: In theory, spreadsheets have almost unlimited capabilities and can save time in all kinds of ways. But in order to actually unlock those capabilities, users need to know the right formulas and commands to use to create the outputs they need, which can ultimately have a very steep learning curve as the complexity of the user's needs grows. Which is why there is all kinds of software on the market that essentially replicates various spreadsheet functions, from rebalancing to performance reporting to financial planning projections: Although the user can theoretically spend less money by setting up a spreadsheet to perform the task, it's much easier to buy a piece of software that does it all correctly right out of the box.

Similarly, what's often needed for LLM tools is an interface that will simply do what the user needs it to do without needing to learn which prompts will serve up specific types of communications. Which, for example, is effectively what most of the current crop of AI-powered meeting note tools do when they take the text of a meeting transcription and automatically convert it into a bullet-pointed summary and list of follow-up tasks: In theory, all that could be done more cheaply by transcribing a meeting recording and dumping it into ChatGPT, but it's much easier to pay for a tool that does it all for you.

In that vein, it's notable that the financial planning platform Libretto has announced a new feature where advisors can click a button to generate a personalized client letter based on the client information that's already embedded in the planning software. Advisors can choose between a number of templates and planning topics to discuss in the letters, such as whether the client is prepared for a market crash or recession or whether their portfolio is on target, and the letters come with charts and graphics to help the clients better visualize the material in the letter.

Libretto's letter feature is a good example of a type of tool that's sorely needed with the inundation of AI into everyday technology, which is something that works with a click of a button and doesn't require a user to iterate on different prompts until they get the output they need. Because again, while an advisor can theoretically create a similar letter directly in ChatGPT by entering the right combination of information and prompts, it's a lot easier when the software that already holds the client information can just do it without any prompting involved on the user's part.

It's worth noting that there's a limit to how far an advisor would want to go with this concept, since it's one thing to use an AI-generated letter to replace email communication (e.g., responding to a client's question about their portfolio positioning), and another thing to use it to replace what would normally be a conversation (e.g., discussing whether the client has enough assets saved for retirement). Likewise, even a "one-click" letter would still likely require a review and editing pass from the advisor to ensure that it's technically accurate and aligns with the advisor's own views on the topic.

Still, there's real value in a tool that can help to streamline the way advisors make use of LLM technology. Even though a chatbox-style LLM can be a powerful tool in the hands of someone who deeply understands the art and science of prompting, not everyone aspires to be that kind of power user. Which means that as advisors grow more comfortable and capable with AI, there will be a growing market for tools like Libretto's letter writer that give advisors access to the AI's capabilities without needing to become AI experts themselves.

Tech Providers Are Starting To Push Agentic AI, But Do We Really Just Need Better UX And Automation?

At times over the past two years it's felt like technology development has gone into hyperdrive mode, as AI tools first burst into the mainstream with chatbot-style Large Language Models (LLMs) such as ChatGPT, and now increasingly are becoming embedded into much of financial advisors' everyday technology. The most prominent example is in the client meeting notes category, which went from zero to (at last count) 12 different advisor-specific tools on the Kitces AdvisorTech Map in just two years, but AI has more quietly become embedded into other tools as well, from planning tools like FP Alpha's AI-powered NextGen Tax Insights to AI-embedded CRMs like Practifi to all-in-one platforms like Orion launching an AI-powered meeting prep tool.

With AI spreading through the industry so fast, it's been natural to occasionally take a step back and wonder whether it's all really necessary, and whether AI will really become a permanent feature of everyday technology, or whether it's just a hype bubble that will burst at some point and all of those AI tools will prove too expensive to maintain at a price that people will pay for them once the flood of venture capital funding that's kept them afloat starts to dry up. At this point, however, as advisors appear to be becoming more comfortable with the use of AI, and as AI becomes more embedded in the tools advisors use every day, it seems likely that even if there is a pullback at some point, AI will still have some kind of presence in the advisor technology landscape – even if, given the still-rapid pace of change, we don't know exactly what that presence will look like yet.

According to many tech vendors and investors, the next frontier in AI is what's being referred to as "agentic AI". The definition of agentic AI seems to differ depending on who's being asked, but the way it's often described is as a tool that can take a single request from a user and perform, unprompted, a sequence of tasks that accomplish that request – for instance, booking a flight, responding to a customer service inquiry, or researching and emailing a prospective client. Also according to those same sources, agentic AI is either just a few months from widespread deployment or else it's already here, ready to drastically reduce staffing and overhead costs by eliminating the need for everything from administrative and customer service staff to researchers to software programmers to web designers.

In a financial advisory context, there are essentially two ways that agentic AI could theoretically be employed. But unfortunately, neither of them really seem to make sense for advisors and their businesses anytime soon.

For the first use, there are tasks that are already generally the job of the financial advisor: Finding and meeting with prospective clients, creating and analyzing financial plans for clients, and meeting with clients and giving recommendations. And it's hard to imagine any of those being fully replaced by agentic AI. There's conceivably a role for AI in prospect research (and several AI-powered prospecting tools like FINNY, AIdentified, and Wealthawk, have already emerged in recent years), but the advisor isn't going to outsource prospect meetings themselves to an AI agent; at some point, the advisor still has to show up, build a relationship, demonstrate their trustworthiness, and persuade a prospect to hire them. Likewise, few advisors are going to outsource client meetings with AI. That leaves financial plan creation and analysis, which is often time-consuming and inefficient, but in a fiduciary business where the advisor is professionally accountable (and financially liable) for any advice they give, it's hard to imagine many advisors outsourcing what is usually the primary source of data to back their recommendations to a technology tool that can't be held accountable for any inaccuracies in its output. Which means at best, perhaps the AI tools ‘just' gather the data, input it to the software, and come up with a list of "potential" recommendations for the advisor to consider… a non-trivial value, but likely saving no more than a few hours per new financial plan (when most advisors take on only 6–12 new clients per year).

The other use cases are in areas of the advisory business that are not generally handled by the advisor: Client service, trading operations, compliance, marketing, etc. And while there are places where AI can assist humans who work in all these areas, what that often comes down to is automating certain sets of tasks – e.g., workflows for opening client accounts or money movements, rebalancing client accounts, or going through a pre-meeting checklist. And given how process-based most advisory businesses are operationally, these are not the sorts of tasks that even actually require AI to automate, since they usually follow the same sequence of steps each and every time they're performed… making them more conducive to good 'old-fashioned' business process automation than agentic AI.

For example, imagine that after every client meeting an advisor follows the same sequence of steps: logging their client meeting notes into their CRM; kicking off follow-up tasks to members of their team for each action item; and sending a meeting recap email to the client. Although each of those steps can be individually helped by AI (e.g., meeting note software to convert the meeting transcript into a summary, a chatbot in the CRM to assign tasks without manually creating each one, and an AI writing aid to create the first draft of the email), the whole process doesn't need an agentic AI to complete it, because there's no decision-making involved: It can be achieved much more easily with a simple automation running between the advisor's AI notetaker and their CRM software that runs the exact same sequence for every client meeting. And if the advisor ever needs to change that workflow, it's much easier to do so in the context of an automation (where they can simply add, remove, or edit steps in the predefined sequence) than it is with an AI tool that must be re-trained with a series of prompts on how to do its job differently.

In other words, while it's easy for tech platforms and their users to be drawn in by the shiny new object of agentic AI, it's worth wondering for every function that AI purports to perform whether it's really necessary for an AI agent to do it – that is, does it involve real decision making on behalf of the technology and applying the wants and needs of the user to the circumstances at hand? – or if the AI is really just being used to patch over a lack of meaningful integrations or automation capabilities or poorly designed UX that makes it harder than it ‘should' be for an advisor to accomplish a task or workflow. Because as it stands in the advisory business, the actual functions that can or should be handled by an AI agent seem fairly limited – either because they're already core parts of what the advisor does, they shouldn't be done by AI because they're central to the advisor's fiduciary duty, or they're really just automations that could be done more easily with a better user interface in lieu of AI altogether?

In the meantime, we've rolled out a beta version of our new AdvisorTech Directory, along with making updates to the latest version of our Financial AdvisorTech Solutions Map (produced in collaboration with Craig Iskowitz of Ezra Group)!

So what do you think? What new features could Altruist implement that it hasn't introduced already? Is "robo planning" more likely to succeed than robo investment advisers, or will it have the same struggles with marketing and distribution? Do advisory firms need agentic AI, or just better automation? Let us know your thoughts by sharing in the comments below!

Leave a Reply