Executive Summary

The IRA aggregation rule was created to limit the ability of taxpayers to take advantage of ‘abusive’ IRA tax strategies, by requiring that all IRAs are aggregated together to determine the tax consequences of a distribution from any of them.

The primary impact of the IRA aggregation rule is to determine how much of an IRA’s non-deductible contributions are treated as an after-tax return of principal when a taxable distribution occurs, whether as a withdrawal or a Roth conversion. And by forcing all accounts to be aggregated together, the rule severely limits many individuals from taking advantage of the so-called “backdoor Roth contribution” strategy.

However, the IRA aggregation rule reaches much further than just the taxability of after-tax contributions in existing IRAs. Thanks to the recent Bobrow case, it now also applies to the limitation of no more than one 60-day rollover in any 12-month period. Though on the plus side, the IRA aggregation rules apply to required minimum distribution (RMD) obligations as well, allowing a distribution from any IRA to satisfy the RMD rules for all IRA accounts!

Fortunately, though, the IRA aggregation rules do not apply when calculating substantially equal periodic payments (SEPP) under Section 72(t), reducing the danger that a withdrawal from one IRA could constitute a “modification” of the ongoing 72(t) distributions from another that would trigger a retroactive penalty. However, even in the case of SEPPs, the IRA aggregation rules will still apply in determining how much of a 72(t) payment constitutes a tax-free return of non-deductible contributions!

What Is The IRA Aggregation Rule?

The IRA Aggregation Rule, under IRC Section 408(d)(2), stipulates that when determining the tax consequences of an IRA distribution – particularly the “pro-rata” rule under IRC Section 72(e)(8) and also the early withdrawal penalty under IRC Section 72(t)(1) – the value of all IRA accounts will be aggregated together for the purpose of any tax calculations. And notably, per IRC Section 408(d)(2)(C), the calculations are done based on the close of the taxable year, which means new contributions or rollovers at the end of the year can impact the tax treatment of withdrawals or Roth conversions that occurred earlier in the year!

Notably, this IRA aggregation rule under IRC Section 408(d)(2) is explicitly only for IRA accounts; employer retirement plans, like a 401(k), 403(b), or profit-sharing plan, are not included in applying these IRA aggregation rules. In addition, under Treasury Regulation 1.408-8, Q&A-9, an inherited IRA is not aggregated together with an individual’s own IRAs, nor is a Roth IRA. And since the IRA rules are applied individually (even as a married couple, the tax consequences are determined individually before being reported on a joint tax return), an individual’s IRA is never aggregated with a spouse’s own IRA accounts.

Given that the treatment of a traditional IRA is that any distributions are pre-tax funds and 100% fully taxable anyway, the IRA aggregation rule is often a moot point. As when a distribution is already 100% taxable, there’s no pro-rata formula to apply, and if applicable at all the 10% early withdrawal penalty would apply to the entire account anyway.

However, as soon as an IRA has any non-deductible (i.e., after-tax) contributions included, the IRA aggregation rule is immediately relevant.

The IRA Aggregation Rule And Pro-Rata Distributions Of Non-Deductible (After-Tax) IRA Contributions

When an IRA has received any non-deductible contributions, the distribution of those dollars is received tax-free as a return of (after-tax) contributions. The amount of any non-deductible contributions that have been made over time is tracked on IRS Form 8606.

The caveat, as noted earlier, is that when a distribution occurs from an IRA that includes non-deductible contributions, the calculation to determine how much of the distribution will be a return of principal must be done on a pro-rata basis under IRC Section 72(e)(8). (Unlike a Roth IRA, where under IRC Section 408A(d)(4)(B) distributions are presumed to come explicitly from after-tax contributions first.)

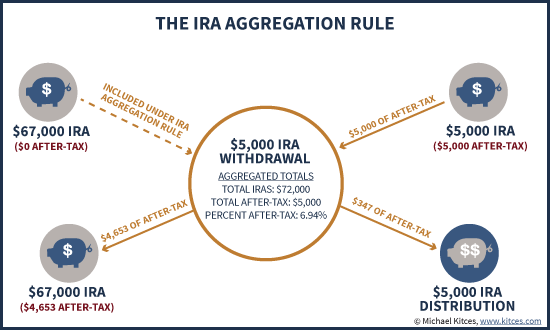

Example 1a. Charlie has a $72,000 IRA that includes $5,000 of non-deductible contributions made years ago, and tracked as such on Form 8606. If Charlie decides to take a $5,000 withdrawal, though, he can’t just take out the $5,000 of after-tax contributions on a tax-free basis (the way he could receive back his after-tax contributions from a Roth IRA); instead, the pro-rata rule applies. Since Charlie’s account is $5,000 / $72,000 = 6.94% after-tax, his $5,000 withdrawal is deemed to be only $347 of after-tax funds (6.9% of the $5,000) and the other $4,653 is taxable. In turn, the remaining $4,653 of after-tax funds remains behind as part of the $67,000 that is still in his IRA account.

Example 1b. Continuing the prior example, assume instead that Charlie had an existing $67,000 IRA that was all pre-tax funds, and had more recently made a $5,000 non-deductible contribution to a brand new IRA #2. But Charlie has decided that he needs to use some of the money, so he now wants to distribute the $5,000 non-deductible IRA, hoping to recover the funds tax-free.

Unfortunately though, even if Charlie withdraws just $5,000 from just IRA #2 that had just after-tax funds in it, the tax consequences are still the same as the preceding example – Charlie’s total IRA accounts are $72,000, his total after-tax funds are $5,000, which means the $5,000 withdrawal will be 6.94% return of after-tax funds with the remainder taxable. Thus, Charlie will end out reporting $4,653 of his withdrawal as taxable, even though he solely converted IRA #2 that originally had only after-tax contributions!

Ultimately, example 1b and the associated chart above show how the IRA aggregation rule plays out when multiple IRAs are involved. Even a distribution comes from an account that was otherwise 100% funded with non-deductible after-tax funds, it still ends out being partially taxable if/when any other IRAs are aggregated into the calculation! And notably, the end result of this strategy in the example above is that the remaining $4,653 of after-tax funds not treated as being part of the withdrawal from IRA #2 have effectively be transmuted into after-tax contributions associated with IRA #1 (even though the contributions were never made to that account in the first place!)!

The IRA Aggregation Rule And Roth Conversion Strategies

Notably, the IRA aggregation rule doesn’t just apply to taxable withdrawals from an IRA. The aggregation rule applies to any taxable distribution/event from the IRA, and under IRC Section 408A(d)(3)(C) a Roth conversion is treated as a taxable distribution. Thus, if in Example 2 if Charlie’s goal had been to convert the $5,000 non-deductible IRA contribution, rather than just withdraw it, the same tax consequences would apply – even if Charlie just converted the $5,000 IRA #2 that contained only after-tax contributions, the conversion would have been treated as $4,653 taxable, only $347 of after-tax funds, and the remaining after-tax money that had originally gone to IRA #2 would now be treated as being associated with the other IRA instead!

This caveat of applying the IRA aggregation rules to Roth conversions can be especially problematic in situations where someone is trying to engage in the so-called “backdoor Roth contribution” strategy, where a high-income saver contributes to a non-deductible IRA with the intention of converting it shortly thereafter, effectively making a Roth contribution while circumventing the income limits that normally apply to a Roth contribution. The problem is that if the saver already has other existing IRAs (ostensibly with pre-tax dollars), those IRAs will be aggregated together with any new non-deductible contributions when the conversion occurs, effectively limiting the strategy.

Example 2a. Jenny is a high-income earner with over $300,000/year in wages, rendering her ineligible to make a Roth IRA contribution. However, Jenny can still make a contribution to her IRA, and while her income combined with her active participation in an employer 401(k) plan limits the ability to deduct the IRA contribution, she can always make a non-deductible contribution as long as she has any earned income. Accordingly, she decides to contribute $5,500 to her (non-deductible) IRA, and then after waiting an appropriate period of time to avoid the step transaction doctrine, she converts the IRA to a Roth IRA. And since the IRA was funded entirely with non-deductible contributions, there is no tax due for the Roth conversion (except to the extent of any gain between the time of contribution and subsequent conversion). The end result – Jenny put $5,500 into her Roth IRA for the year, and while she didn’t get a tax deduction (that she couldn’t have gotten anyway), she didn’t owe any more in taxes either and got the maximum contribution into a Roth!

Example 2b. Continuing the prior example, assume that Jenny also had $200,000 of existing (pre-tax) IRA funds in place. Now, when Jenny makes a $5,500 non-deductible contribution and then attempts to convert it, she cannot convert just the $5,500 IRA (when she contributed to the existing $200,000 IRA or funded a new separate account); instead, her conversion is subject to the IRA aggregation rule, and the tax consequences are determined on a pro-rata basis across all the accounts. The end result: since Jenny’s total $5,500 non-deductible contributions are only 2.68% of her $205,500 total IRA accounts, the conversion of the new IRA will be treated as only $147 of after-tax, and $5,353 of pre-tax funds that are taxable at conversion! The existence of the other IRA, due to the IRA aggregation rule, has eliminated Jenny’s ability to engage in the backdoor Roth strategy!

Notably, though, since the IRA aggregation rule only applies to IRA accounts, Jenny does have a potential workaround – she can roll over the existing pre-tax IRA funds into an employer retirement plan, which separates them from the IRA-only aggregation rule. Once rolled over, she can now convert the remaining now-just-non-deductible funds in the IRA, to complete the Roth transaction. And in point of fact, the rules under IRC Section 408(d)(3)(A)(ii) explicitly state that when a rollover occurs from an IRA to an employer retirement plan, the pro-rata rule does not apply and the pre-tax funds are rolled over first. Which means, ironically, the rules operate perfectly to allow any ‘unwanted’ pre-tax dollars to be “siphoned off” from the IRA to a 401(k) or other employer retirement plan, so the after-tax remainder can be converted! The caveat, of course, is that the strategy is only feasible if the saver has an employer retirement plan that accepts roll-ins in the first place!

Example 2c. Continuing the prior example, Jenny has just made her $5,500 non-deductible contribution to her existing $200,000 IRA, and now realizes the problem that the IRA aggregation rule presents. To resolve this, she contacts her employer and confirms that she is able to make a rollover contribution from her IRA to her current employer’s 401(k), and proceeds to do so for the entire $200,000 of pre-tax dollars in her IRA. Once the roll-in is completed, Jenny is left with a $5,500 IRA, which now includes only the after-tax dollars (because the roll-in to the 401(k) siphoned off all the pre-tax dollars!). Jenny can now convert the $5,500 IRA to a Roth, and because it still contains only after-tax contributions, there is no tax liability on the conversion!

Bobrow v. Commissioner, The Once-Per-Year IRA Rollover Rule, And The IRA Aggregation Rule

In the past, the IRA aggregation rules were applied primarily for the purpose of determining the tax consequences of a distribution (or Roth conversion) that included after-tax contributions. But thanks to the recent court case of Bobrow v. Commissioner, the IRA aggregation rule is now used in the context of the once-per-year IRA rollover rule, too.

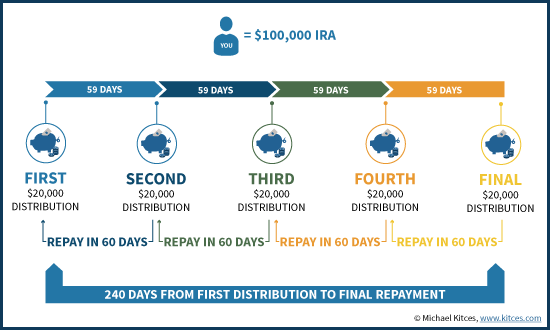

The once-per-year IRA rollover rule states that when a distribution occurs from an IRA and it is rolled over within 60 days (under the normal rollover rules), another rollover cannot occur for the next 12 month period (measured from the day the distribution occurred). In the original interpretation of these rules – and as previously explained in IRS Publication 590 – the Service had interpreted this rule to mean that no additional rollovers could occur from either the IRA that the distribution came from, or the IRA that the new funds went to. However, if the taxpayer had another entirely separate and unrelated IRA, that IRA could still engage in another rollover. And some people had actually used this rule to chain together multiple IRA rollovers (where IRA #2 repays IRA #1, then IRA #3 repays IRA #2, then IRA #4 repays IRA #3, etc.), effectively extending themselves a long-term “temporary” loan.

However, in the Bobrow case, the Tax Court reviewed the strategy (after Bobrow made a mistake in executing it, raising the attention of the IRS in the first place), and declared that the IRA aggregation rule under IRC Section 408(d)(3) should apply for the purposes of the once-per-year rollover rule, not just in the context of calculating the pro-rata tax consequences of an IRA distribution.

As a result of the court’s ruling, the IRS declared in IRS Announcement 2014-15 that starting in this current year of 2015, any IRA distribution-and-60-day-rollover from any IRA will render all of the taxpayer’s IRAs ineligible for another 60-day rollover in the next 12 months! Notably, since the IRA aggregation rule only applies to IRAs and not employer retirement plans, a distribution-and-60-day-rollover from an employer retirement plan does not trigger this rule, but any other IRA distribution-and-rollover does. In addition, it’s important to remember that a trustee-to-trustee transfer is not treated as a 60-day rollover, and consequently there is still no limit on the number of trustee-to-trustee “rollover” transfers that can occur within a year. But for any situation where the taxpayer actually takes possession of the money as a distribution, and then rolls the funds over within 60 days, the IRA aggregation rule applies to render all IRA accounts ineligible for another 60-day rollover for the next 12 months!

The IRA Aggregation Rule And Satisfying Required Minimum Distribution (RMD) Obligations

While in most contexts the IRA aggregation rule “complicates” situations by limiting proactive tax strategies (e.g., eliminating the sequential-60-day-rollovers-as-loans strategy, or the backdoor Roth contribution strategy), when it comes to required minimum distributions (RMDs) the IRA aggregation rule is actually helpful.

The reason is that under Treasury Regulation 1.408-8, Q&A-9, an IRA owner can satisfy the required minimum distribution obligations for all of his/her accounts by taking those RMDs from any of the accounts. In other words, thanks to the IRA aggregation rule, a distribution from any IRA can be applied towards satisfying the required minimum distribution from all IRAs!

Example 3. Harriet just turned 75-year-old this year, and has two IRA accounts; the first, with a value of $175,000, is invested into a variable annuity with a guaranteed minimum income benefit rider, and the second is held in a $40,000 CD. Under the Uniform Life Table in Appendix B of IRS Publication 590, Harriet’s RMDs this year will be $175,000 / 22.9 = $7,642 from her IRA annuity, and $1,747 from her IRA CD, for a total RMD of $9,389. However, thanks to the IRA aggregation rule, Harriet can actually withdraw $9,389 from any of her IRA accounts to satisfy this RMD obligation. As a result, if she wants to not withdraw from the IRA annuity – although often unfavorable, perhaps she prefers to wait on the annuity income distributions and allow the GMIB rider to continue to accrue its guaranteed income floor – she could choose to take all of the $9,389 RMD from just the IRA CD, and still satisfy her RMD obligation.

This flexibility to satisfy the RMD of all accounts by taking an RMD from any one of them can be highly valuable in situations where there are multiple IRAs but one holds assets that are less liquid, whether it’s an annuity with various guarantees that would be adversely impacted by a withdrawal, or a piece of illiquid real estate. The retiree can use the IRAs that are liquid to satisfy the RMD obligations for all the accounts, without touching the particular IRA assets that would be better to just hold in place.

Notably, though, since the IRA aggregation rule only applies to an individual’s own IRAs – whether for the purposes of calculating pro-rata distributions of after-tax dollars, or for RMD purposes – an RMD taken from one IRA may not satisfy the RMD requirements of any inherited IRAs, a spouse’s IRA, or any employer retirement plans (e.g., a 401(k), 403(b), profit-sharing plan, etc.). In the case of those other accounts, each of those accounts must still take its own RMDs attributable to the value of that account directly from that account.

When The IRA Aggregation Rule Does Not Apply – 72(t) Substantially Equal Periodic Payments (SEPP)

Notwithstanding the wide scope of where the IRA aggregation rules apply, one notable situation where aggregation does not have to be considered is when an early retiree is taking early withdrawals from an IRA under the substantially equal periodic payment (SEPP) rules of IRC Section 72(t)(2)(A)(iv).

Instead, under PLR 200309028, the IRS explicitly stated that IRAs are handled on an account-by-account basis when doing substantially equal periodic payments. This is important for situations where an individual is doing 72(t) payments from one IRA, and then wants to take additional distributions, or begin new 72(t) payments from an additional IRA; if the accounts were aggregated, changes to the second account could be construed as a modification to the first, triggering retroactive penalties as the substantially equal periodic payments are disqualified. Instead though, because the IRA aggregation rule does not apply, each account is treated separately to determine the appropriate amount of distributions under 72(t), and changes to distributions from another account do not impact (or constitute a modification to) ongoing withdrawals from a current account engaged in SEPPs.

On the other hand, it’s worth noting that while IRA accounts are not aggregated together in determining the required amount for substantially equal periodic payments, or whether withdrawals from other accounts constitute a modification to the original 72(t) payments, the IRA aggregation rule would still apply in determining the tax consequences of those distributions. In other words, if any of the IRAs have after-tax contributions, even the ongoing 72(t) substantially equal periodic payments will be subject to the pro-rata rule on an aggregated basis, even though the calculation of the 72(t) payments continues to be done on an account-by-account basis!

Example 4. Gerald is a 56-year-old with two IRAs, the first worth $400,000 (all pre-tax), and the second worth $11,500 that includes $10,000 of non-deductible IRA contributions made in recent years. Gerald is currently taking $15,000/year of distributions from his first ($400,000) IRA, using the 72(t) substantially equal periodic payments exception to avoid an early withdrawal penalty (which would otherwise apply, since he is under the age of 59 ½). While for the purposes of the 72(t) the $400,000 IRA is handled separately from the second $11,500 IRA, the tax consequences of the $15,000/year distribution is still subject to the IRA aggregation rule in calculating the pro-rata allocation of after-tax funds. Thus, since $10,000 / $411,500 = 2.43% of the total accounts are after-tax, each $15,000 withdrawal will be treated as $365 of after-tax and $14,635 of pre-tax funds, even though all the 72(t) distributions are being taxed from an account that was originally funded exclusively with pre-tax dollars!

So what do you think? Have you had situations where the IRA aggregation rule created a challenge? Did you come up with a workaround? What questions do you have about the IRA aggregation rule? Leave your questions/comments below!

Michael, one word but important typo in first sentence:

but requiring that all IRAs

You mean “by requiring”

Ack, indeed! Thanks – fixed now!

– Michael

I’m so glad that since tomorrow is 10/15 that my current 8606 will be one year older and more mature since I have settled on my converted IRA tax due and recharacterized the load that reduced in value during the last few months of this 25 month cycle. Another personal tax victory for myself and primary clients. Unfortunately the tax code is seemingly to me far too complicated. NICE work Michael you help us stay on our toes. See you in Jan 16. No needs.

I believe the total IRA value is determined as of December 31 – not as of the time the withdrawal or Roth conversion is made. This is a key timing point that needs to be understood as part of any of the stragegies discussed.

Michael, can you confirm that IRA dollars need to be rolled to qualified retirement plan by 12/31 of a current year in order to do a ND to Roth IRA even out to 4/15 on the next year for the previous year?

Has anyone seen a definitive answer for this question? If an IRA balance is rolled into an employer plan in 2020, is a Roth conversion of a ND contribution tax free based on IRA balances of $0 as of 12/31/2020? I just want to make sure that the rollover to the employer plan during the same tax year won’t cause tax to be incurred on the conversion.

Another great lesson, Michael. Thanks!

Michael,

In example #4 at the end of the article, how is it possible that Gerald would be able to withdraw $15,000 of all pretax dollars yet only be taxed on $14,635 ? If the example was $400,000 pretax account and $400,000 after tax account, and he took out $15,000 from the pretax account only, he would be taxed as if he had only taken out $7,500 pretax ? It sounds like Gerald has found a way to never pay taxes on the pretax contributions. Am I missing something ?

Eric

Eric,

Because the whole point here is that Eric did NOT withdraw $15,000 of all pre-tax dollars. He can’t. That option doesn’t exist.

Eric has $411,500 of TOTAL dollars, of which $11,500 are after-tax. That is true regardless of any account from which he withdraws.

So he’s taking a $15,000 withdrawal from $411,500 of TOTAL dollars that include $11,500 of after-tax. Under the pro-rata rules, that means $14,635 is pre-tax, $365 is after-tax, and once the withdrawal is completed, his IRAs have a remaining value of $411,500 – $15,000 = $396,500, and his remaining after-tax allocation is $11,500 – $365 = $11,135.

I hope that helps a little?

– Michael

Michael,

Thank you for the clarification and your patience. I am not a financial professional, just an investor trying to stay on top of the tax implications of handling multiple accounts of pretax, after-tax, and Roth. They have made it so complicated I will have to utilize a pro when I retire, but I want to have a basic understanding when that day comes. I enjoy your articles.

Eric

Good stuff Michael. I am learning a bit more about my IRA because of my growing pension. Not touching it of course and I am not changing my strategy, but it always helps to get the facts. Appreciate it.

Ryan

Michael – can you comment on an example of the “back door” Roth contribution given this rule?

– Individual is an active participant qualified retirement plan (i.e. their company’s 401k)

– Has pre-tax Traditional IRA assets

– Cannot make deductible IRA contribution or contribute to Roth because of income

– Rolls over all his IRA to the QRP as long as the plan accepts the assets

– He/she now has zero pre-tax IRA dollars and can convert non-deductible IRA contribution to a Roth with very little or no tax impact

Is there any timing issue between the rollover of the IRA to the plan and the contribution/conversion to/from the IRA? Or anything else to consider?

thanks

I believe the 60-day rule doesn’t apply for rollovers of an IRA to QRP. It only applies to IRA-to-IRA rollovers. A contribution/conversion is not a rollover, so that wouldn’t apply either.

I agree..

ddd

Got a special case. Doing a backdoor Roth conversion correctly (all money previously rolled into an employer plan). Turns out, the value of the assets being converted exceeds the basis. So… No profit on the Roth conversion and no tax. The loss has no value as a tax write off. (Subject to 2% misc deduction limit)

But can’t I take a rollover a small portion of my employer plan (equal to the amount of my negative basis) and then convert that to a Roth, also? Since the employer plan is pretax, and has a tax basis of zero, in theory I’d have to pay tax on the value. But since I had negative basis from the previous backdoor Roth conversion, don’t the two offset?

when is the taxable determine at time of conversion jor at the end of the year? I had a 6,500 balance in my IRA all Post tax from 2014 contribution. I converted it to my Roth IRA in March 2015. I then rolled 21,000 pre tax money to my IRA from my 401k in August 2015. Since my IRA was 100% post tax at the time of the conversion what amount of the conversion to the Roth is taxable?

Does anyone know if an IRA Annuity is also included in the total IRA when calculating the pro-rata conversion? thanks,

An IRA annuity is an IRA like any other IRA when calculating the pro-rata taxable amount for a distribution or a conversion. The fact that the IRA happens to own an annuity (and not a stock, or a bond, or a CD) is irrelevant in this context.

– Michael

I have a roth withdrawal question. I have 2 separate roth accounts. Contributed upto the limit ($5500) to each in separate years. One account has grown and the second account is down from the original $5500. Can I take a tax free/penalty free withdrawal upto my total contribution of $11000 out of the account that’s sitting with a gain?

It doesn’t matter; it’s all aggregated.

This line needs more clarification “IRA aggregation rule only applies to IRA accounts”. Instead I believe it applies to only all traditional and simple ira’s not Roth IRA so it should be like this “IRA aggregation rule only applies to all Traditional and Simple IRA accounts”

Another special case concerning substantially equal payments. I understand that the aggregation rules don’t apply for substantial equal payment purposes. However, is it optional for an individual to aggregate two or more IRAs for purposes of calculating substantially equal payments? That is, can he calculate the payments based on the sum of two balances and take the distribution from just one of the IRAs?

Here is a tricky scenario:

I have a client who is from Canada but hasn’t lived there in many years. He has all of his retirement / qualified savings held within his company 401(k) with no IRAs currently set up (we would set them up if he can fund backdoor contributions). We want to start funding a backdoor Roth IRA and don’t know if the roughly $18k he has in a Canadian RRSP account will be included in the calculation when converting the non-deductible contribution to his Roth IRA? We’ve checked with the clients CPA and after a week of research concluded they wouldn’t be able to give an opinion. Does anyone have experience with this specific scenario? Thanks.

Please help:

In 2016, I had $18k in traditional rollover IRA, and $12k in Roth IRA, from the days that I could still make Roth IRA contributions. In January 2017, I rolled-over my $18k trad IRA to my employer-sponsored 401k.

I got married in July 2016 and my wife has no IRA accounts.

Since I had traditional IRA assets as of Dec 31, 2016, can I still make a non-deductible IRA contribution for 2016 and convert to Roth in 2017?

Would I incur taxes on the Roth conversion due to IRA aggregation rules?

My wife makes minimal income. Can she make a direct Roth IRA contribution, or does she have to make a backdoor Roth IRA due to my income exceeding the Roth IRA contribution limit?

Thank you.

The only way that you were able to rollover the TIRA into a 401K is if that TIRA was actually a rollover TIRA (i.e., rolled over from a 401K). Your new employer would not have allowed this to happen if this had not been true.

It doesn’t matter that you have TIRA assets. The only restrictions that come into play is if your employer offers a 401K and of course, income level.

If one completes and IRA rollover in January of the year and all the existing IRA assets are non-deductible what happens if sometime later that year a pre-tax 401k is rolled into an IRA and assume on 12/31 there is a balance in the tax-deferred IRA (from the roll-over). Should I assume the pro rata rules not apply since at the time of the conversion the balance was $0 or would I just look at the balance on 12/31 to determine the pro rata amount?

By “IRA rollover”, if you mean back to the same type of IRA (i.e., TIRA or Roth) AND that you followed the rules for such rollovers, then it’s like nothing had happened, even if the rollover goes over the new year. (You would have to include a letter specifying this as your custodian would not report this situation.)

I have rollovered my 401k to annuities, do these annuities be included in IRA aggregation?

I rolled over my employer 401K into an IRA in 2004. The Total Distribution Statement for the 401K shows a total of $90,000 in After-tax matched and After-tax unmatched contributions. It also shows $30,000 in Return on After Tax. In 2004 I received a 1099R from Fidelity showing the full Gross Distribution and also showing $30,000 on LIne 5 “Employee contributions or insurance premiums”.

Now I would like to start moving $ from the IRA to a Roth IRA and I need to know the amount of after-tax money I have in the IRA. It seems to me it is $90,000.. Is that correct?

Looks like the $90K includes gains on the employee contributions. That explains it.

I have a $100k 401k from my previous employer of which $60k is non-taxable Roth Deferral contributions, $15k is employer contributions, and $25k is gains. I am planning on rolling over the $100k to my new employer 401k. Is there a way to distribute just the $60k contribution basis (and avoid taxes and penalties) either during the rollover process or direct from the new 401k? Or will this all be aggregated such that the $60k would get taxed on a pro rata basis with no way of getting around it?

Question my husband has a SEP IRA for his business which has no employees. I have a 401k at my employer and have traditionally contributed to a traditional IRA and immediately converted those funds to a ROTH IRA. My original investment firm had no problem with it but my new firm is saying that the aggregation rules apply and the entire amount of my conversion is taxable even though it is all contributed and converted immediately. My question is does the aggregation rule apply to couples who file MFJ even if the SEP IRA is in the husband’s name and the Traditional and ROTH IRAs are in the spouse’s name? Just trying to make sure i have been handling my taxes properly and if it is taxable regardless then the backdoor ROTH is really not doing me any good and I will stop doing it.

Felicia,

The IRA aggregation rule applies to all of YOUR IRAs, but not your husband’s IRAs. Individual tax rules are applied on an individual basis. There are no joint IRAs.

– Michael

Do the aggregation rules apply to Annuities? I have an old SEP IRA that only has a non qualified annuity in it, to which I have not contributed for over 15 years. I would like to do back door IRA contributions and plan to rollover all of my other IRA accounts into my employer plan but I can’t do that with the Annuities.

This is a great blog! I am “early retired” and actually used the Bobrow scheme in years X+3 & X+4 to defer the distribution of about $26K from my Roth until a big Roth conversion in year X attained the 5-year seasoning. I split my net IRA into 10 accounts with an average of 45 days between rollovers, so I gave myself plenty of time to spare; being “retired” I was able to be diligent in setting up a proper spreadsheet file and doing the actions at the proper time, and figure that the $2600 in 10% penalty that I had saved cost me about 100 hours in labor (fortunately my custodian had no-fees!) As one might imagine, I was extraordinarily interested in the Bobrow case, and as it turned out, I was barely able to use it through to its fruition. WHEW!

I am now considering purchasing a home with my (almost completely converted out) Roth IRA, and although I think that with my very low cash burn-rate I will have enough 5-year seasoned Roth conversion for me to make it to the golden age of 59-1/2, it might turn out that it would be in my best financial interest to do a 72(t) plan to get me over that hump, and the fact that I can consider a single Roth account as the 72(t) source while I completely do whatever I want with my other accounts is great news. That said, it seems that even though such distributions would be without penalty, they still would be considered as “non-qualified”, and therefore would be counted against the conversion basis. Oh well, at least Roth distributions don’t count against means-tested benefits like the ACA (i.e., ObamaRomneyHeritageCare), so by being totally in Roth, I get to get on the Medicai expansion for FREE.

Hi Michael,

Quick question regarding the rollover into 401(k) to avoid pro rate calculation for Roth conversions. I read somewhere that the portion that can be rolled over into your 401(k) from an IRA can only consist of money that was rolled over from a previous 401(k) plan. For example, if I have an IRA account with a balance of $100,000 and $60,000 consists of money that I rolled over from a previous 401(k) and the other $40,000 are from contributions then I am only able to roll over the $60,000 into my current 401(k)? Is this true? If so, do you know what are the repercussions if you roll over the full $100k from my example?

Hello, Michael! I have a client who is converting a SEP-IRA to a SOLO 401K. Once the rollover is completed she will no longer have any “IRA” accounts. The SOLO 401K I am setting up is NOT an ERISA plan. Does a non-ERISA 401K still count as a QRP for the purposes of NOT including its balances when doing Roth conversions? Once she only has a SOLO 401K my intentions are to fund non-deductible IRAs and then convert. I simply want to rule out any potential “tainting” of this strategy because the 401K of choice is not an ERISA plan. Thank you! Kraig R. Mickelsen

Hi,

The below still true?

the rules under IRC Section 408(d)(3)(A)(ii) explicitly state that when a rollover occurs from an IRA to an employer retirement plan, the pro-rata rule does not apply and the pre-tax funds are rolled over first. Which means, ironically, the rules operate perfectly to allow any ‘unwanted’ pre-tax dollars to be “siphoned off” from the IRA to a 401(k) or other employer retirement plan, so the after-tax remainder can be converted! The caveat, of course, is that the strategy is only feasible if the saver has an employer retirement plan that accepts roll-ins in the first place!

great blog, thanks

Is there a rule about doing a roth conversion when you own multiple IRAs? For example if I convert 5% of one of my traditional IRAs do I also have to convert 5% of the other traditional IRA if I have two? Thank you

Nice article Michael. Is Example 2b wrong?? If the $200K in separate traditional IRA is all pre-tax the aggregation rule should not apply.

How would the aggregation rule apply in the scenario of MEGA backdoor Roth conversion?

Suppose one contributes to the AFTER tax traditional 401k through their employer, and the employer's retirement savings plan allows these contributed funds to be rolled over to the Roth IRA, while still being employed with them. The same individual also has traditional IRA accounts with pretax funds in them.

If this individual is performing rollovers of their aftertax 401k contributions to Roth IRA, would aggregation rule apply, taking into account they have traditional IRAs with taxable funds?

On the one hand, the aggregation rules are always described as the rules applicable to the rollovers from/to IRA accounts, and your article mentions several times that the aggregation rule does not apply to 401k accounts. On the other hand, the provided examples illustrate the situation when the funds in 401k are excluded from the taxable funds total in the aggregation rule application. However, in the above situation, the 401k account is the account from which the rollover originates, but the taxable funds are still present in traditional IRA accounts.