Executive Summary

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), passed in 2017, was one of the most extensive pieces of tax legislation to be passed in the last 30 years, touching many aspects of individual, corporate, and estate tax. However, most of TCJA's provisions are set to 'sunset' at the end of 2025 – an event that would have at least as much impact as TCJA's initial passage.

From an advisor's perspective, TCJA's impending expiration raises the importance of planning for clients who will potentially be impacted, which, given the law's broad scope, could be nearly every client. And yet, the timing of the sunset provision at the end of 2025 means that the actual fate of TCJA will largely hinge on the uncertain outcome of the 2024 U.S. elections. In reality, any law that extends or replaces TCJA would likely not pass until well into 2025, creating a very limited window (potentially only days long) in which to implement any planning strategies. And so even though there's uncertainty today about whether or not TCJA will sunset as scheduled, it's still not too early to start making plans for either contingency so they can be triggered quickly once there is more certainty.

For many clients, one of the biggest questions is whether they'll have a higher or lower marginal income tax rate after TCJA expires than they do today, and whether it is therefore reasonable to accelerate income – i.e., to recognize it before the end of 2025, such as by converting pre-tax retirement funds to Roth – or to defer income to be recognized in 2026 or beyond. And although TCJA's reputation as a broad tax cut might give the impression that everyone's tax rates would increase after its expiration, comparing the current Federal tax brackets with their estimated post-TCJA equivalents shows that a fair number of households will actually see their tax rates decrease.

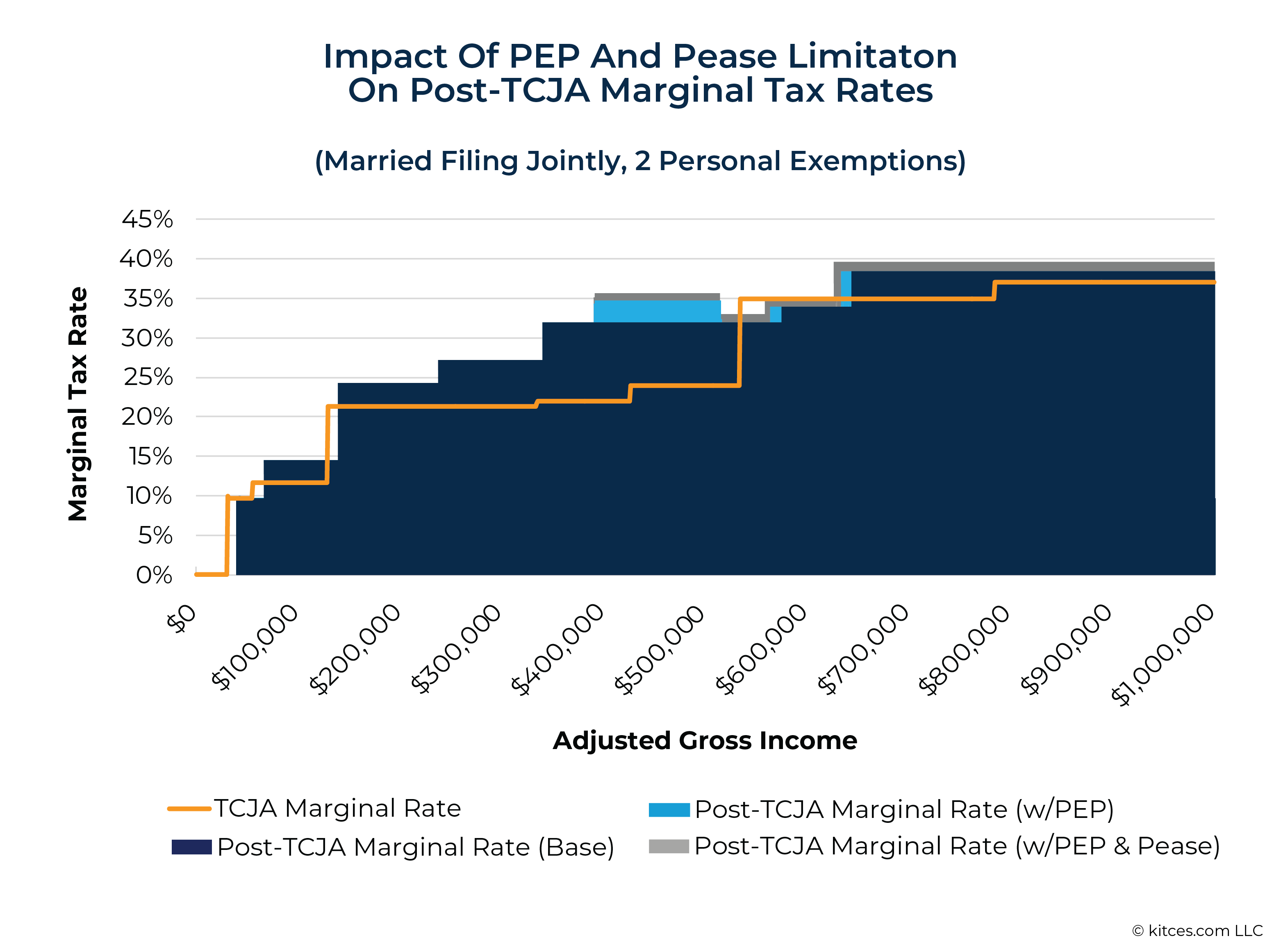

Beyond the tax brackets themselves, however, households will also see significant changes to how their taxable income is calculated post-TCJA. First, the combination of a lower standard deduction and the elimination of the $10,000 cap on deductible state and local tax payments means that many more people will be taking itemized deductions instead of using the standard deduction. Second, the reinstatement of personal exemptions means that households will be able to take an estimated $5,010 exemption per taxpayer or dependent, meaning that larger households could see a large reduction in their taxable income. With the caveat that the expiration of TCJA will also bring back the Personal Exemption Phaseout (PEP) and "Pease limitation" on itemized deductions above a specific income threshold, both of which effectively create a surtax on income within the threshold range, increasing the household's marginal tax rate above their nominal tax rate based on the tax brackets alone.

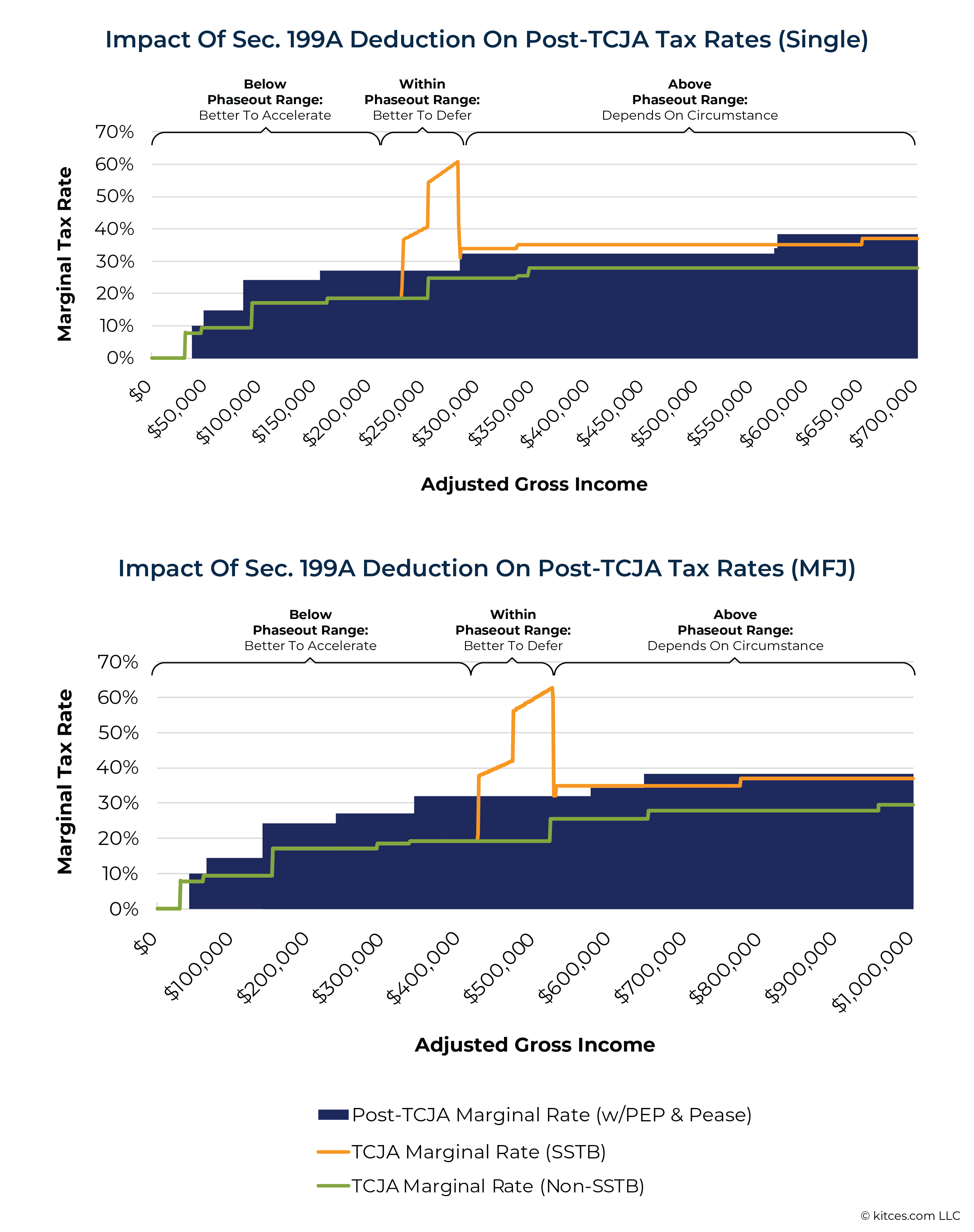

For owners of pass-through businesses like partnerships, S corporations, and sole proprietorships, the biggest concern around TCJA's sunset is the elimination of the Section 199A deduction on Qualified Business Income (QBI), which allowed for a deduction equal to 20% of the lesser of the taxpayer's QBI or their taxable income. For most pass-through business owners, the end of the QBI deduction will result in much higher marginal tax rates in 2026 or later, with one exception: Owners of Specified Service Trades or Businesses (SSTBs) like lawyers, consultants, and financial advisors, whose QBI deduction phases out above certain income thresholds, will have a much higher marginal tax rate on any income earned within the threshold range – meaning that while it might make sense for most business owners to accelerate income in 2024 and 2025 while the QBI deduction is still in effect, SSTB owners within the phaseout threshold range would be better off doing the opposite and deferring income until after TCJA expires.

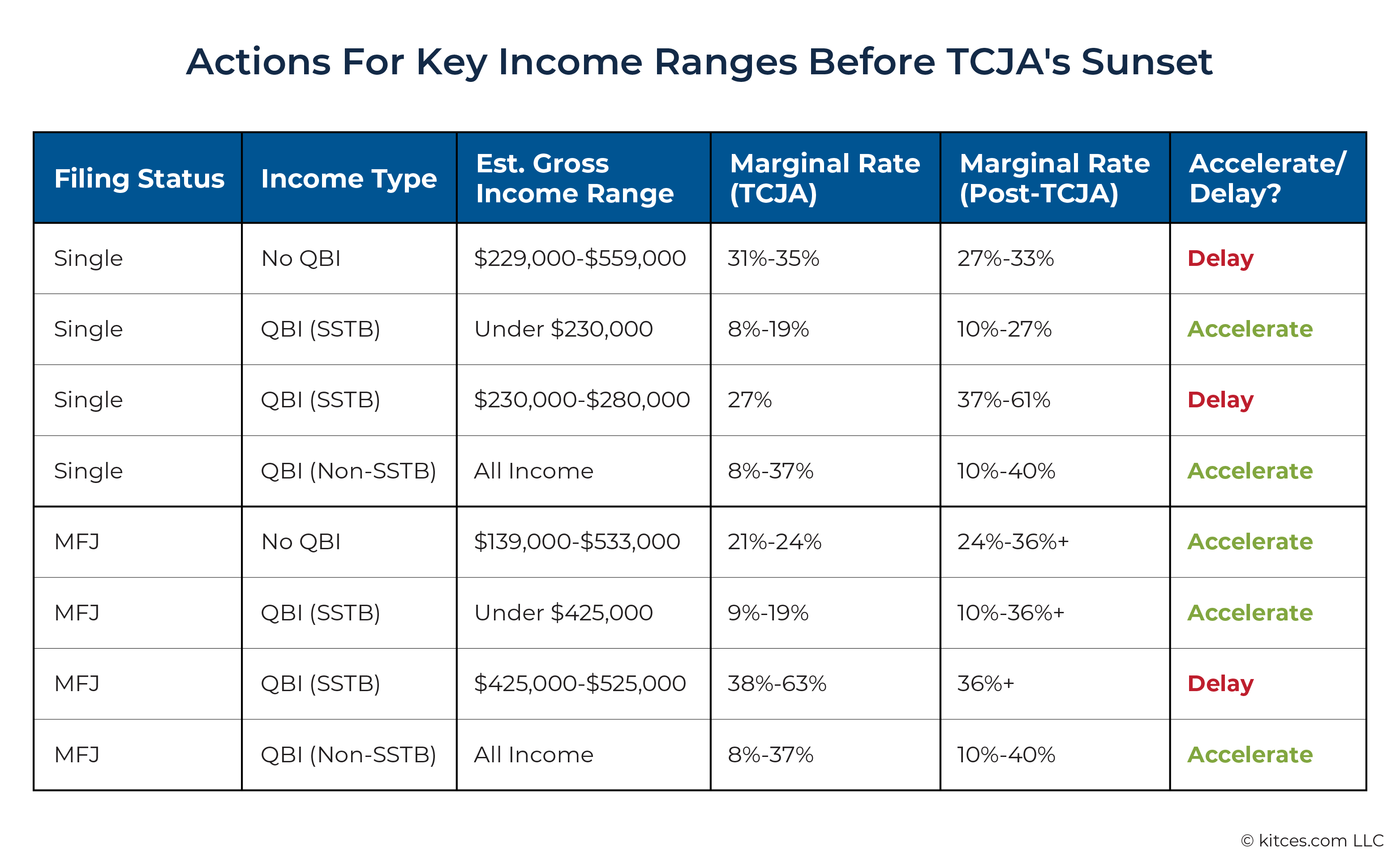

The key point is that different households will experience the end of TCJA in a wide variety of ways, with income level, filing status, number of dependents, and QBI all factoring heavily into the impact that the TCJA sunset will have. And although TCJA's ultimate fate may still be undecided, for at least some clients the potential benefit of taking action today (e.g., to recognize income at a lower marginal tax rate today versus after TCJA expires) may be worth taking the risk that TCJA is ultimately extended – since in that case the client would have simply recognized income at the same marginal rate that they would have later on, merely 'costing' them the value of a few years of tax deferral. So by understanding how each client stands to be affected, advisors can narrow their focus on the planning strategies that will have the biggest benefit for their clients.

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), enacted in 2017, was the most far-reaching piece of tax legislation to be passed in over 30 years since the Reagan-era Tax Reform Act of 1986. It touched many aspects of individual income tax, corporate tax, and estate tax and introduced entirely new planning strategies to make full use of its many components (e.g., business structure and income planning to maximize TCJA's Sec. 199A deduction on Qualified Business Income, deferring or even eliminating capital gains through the use of Qualified Opportunity Funds, and electing state-level Pass-Through Entity Taxes to preserve the deductibility of state and local taxes on pass-through business income).

But despite their wide-ranging impact, TCJA's tax changes were not written to be permanent. In order for the bill's tax cuts to be passed with a simple majority of votes (since the Republican majority at the time lacked the 60 votes needed to overcome a potential filibuster), they needed to lapse within 10 years of taking effect. As a result, the vast majority of TCJA's provisions are scheduled to 'sunset' at the end of 2025.

TCJA's sunsetting at the end of 2025 means that the national elections in November 2024 will decide who will be in Congress and the White House when TCJA is scheduled to sunset, which ultimately will dictate whether some or all of the law is extended beyond 2025 or if it will be allowed to lapse as scheduled. The problem from a tax planning perspective, however, is that no one is certain of what the outcome of this year's election is going to be, or exactly what impact different outcomes will have on the fate of TCJA.

On one end of the spectrum, there could be a trifecta of Republican control over the White House, the Senate, and the House of Representatives, which would likely result in much of TCJA being extended. On the other end, there could be a Democratic trifecta, which would more likely end up with most of TCJA expiring (although President Biden has pledged to extend TCJA's tax cuts for taxpayers earning less than $400,000). And if neither party gains a trifecta – which is arguably the most likely outcome – then the parties will either need to somehow negotiate a deal that's agreeable enough to both sides to garner enough votes for passage, or risk gridlock that results in the entire TCJA sunsetting at the end of 2025.

Ultimately, then, it's useless to try to predict what exactly U.S. tax law will be at the beginning of 2026 since the outcome hinges both on elections that will take place in late 2024 and legislative negotiations that will likely extend deep into 2025. But does the political uncertainty surrounding the TCJA sunset provisions make it impossible to do any tax planning before the situation is resolved in one way or another?

It may be tougher to plan in an uncertain legislative environment, but it isn't impossible altogether. In fact, one of the worst approaches to take would be to simply wait until there's 100% certainty about what the law will be because, at that point, it could be too late to take meaningful action; consider that TCJA itself was signed into law on December 22, 2017, just 10 days before most of its provisions were set to take effect. If Congress takes until that late in the year to pass whatever legislation either extends or replaces TCJA, there may need to be a plan of action in place that can be triggered in the remaining few days, which requires laying the groundwork well in advance and making decisions about what will be done in the event of Plan A, B, or C.

And so while there are, at the time of this writing, about 4 months until the election that will decide who is in power when TCJA expires, and nearly 18 months until the actual sunset date itself, advisors can help their clients by considering tax planning moves that could make sense in the event of TCJA's expiration, with ample flexibility to account for the possibility that some – or all – of the law could be extended.

One of these potential strategies involves deciding when to recognize – or defer – certain kinds of income or deductions. Most of the time, taxpayers don't have a choice about what year they can include income on their tax return: Wage and salary income, Social Security payments, and dividends or interest from taxable investments (just to name a few) are usually out of the taxpayer's control in terms of when they can be received and recognized as taxable income.

However, there are some exceptions where a person can control the timing of their income. For example, someone who makes regular retirement account contributions can decide whether to contribute to a traditional account (where they'll receive a tax deduction this year, and pay tax on the contributed funds plus any accumulated growth when they eventually withdraw them) or a Roth account (where they will receive no deduction this year, but will be able to withdraw the funds tax-free later on), which effectively gives them the choice to recognize the income on those funds today or in the future when the funds are withdrawn.

Similarly, they can decide whether to convert funds that are already in a tax-deferred traditional account to Roth, requiring them to recognize and pay tax on the amount of the conversion but allowing them tax-free growth on the funds going forward. In either case, the economically best option would be the one that results in paying the lowest tax on the income that's recognized, so when an individual expects their tax rate to be lower in the future than it is today, it's better to defer the income (e.g., by making a traditional contribution) in order to recognize it at a lower future rate; whereas if they expect their tax rate to be higher, it's better to recognize the income at the lower rate today (e.g., by contributing or converting to Roth) to in order to avoid paying the higher rate in the future.

And so with the potential for TCJA's sunset to affect the amount of tax paid by nearly everyone, it can be helpful from a planning perspective to start by understanding which clients would potentially see their taxes increase – or in some cases, decrease – to start making decisions around accelerating or deferring income that can be quickly acted on when there's more clarity on whether Congress will extend, alter, or allow the law to expire as planned.

Why TCJA's Expiration Won't Raise Everyone's Taxes

The potent branding of TCJA as a tax cut – it's right in the name! – and the fact that it introduced more tax reductions, deductions, and credits than tax increases gave it a reputation as an across-the-board tax cut – and conversely, created the expectation that everyone's taxes would go up once the law's provisions sunset at the end of 2025. And yet, there are a fair number of situations in which a person's tax rate would go down as a result of TCJA expiring.

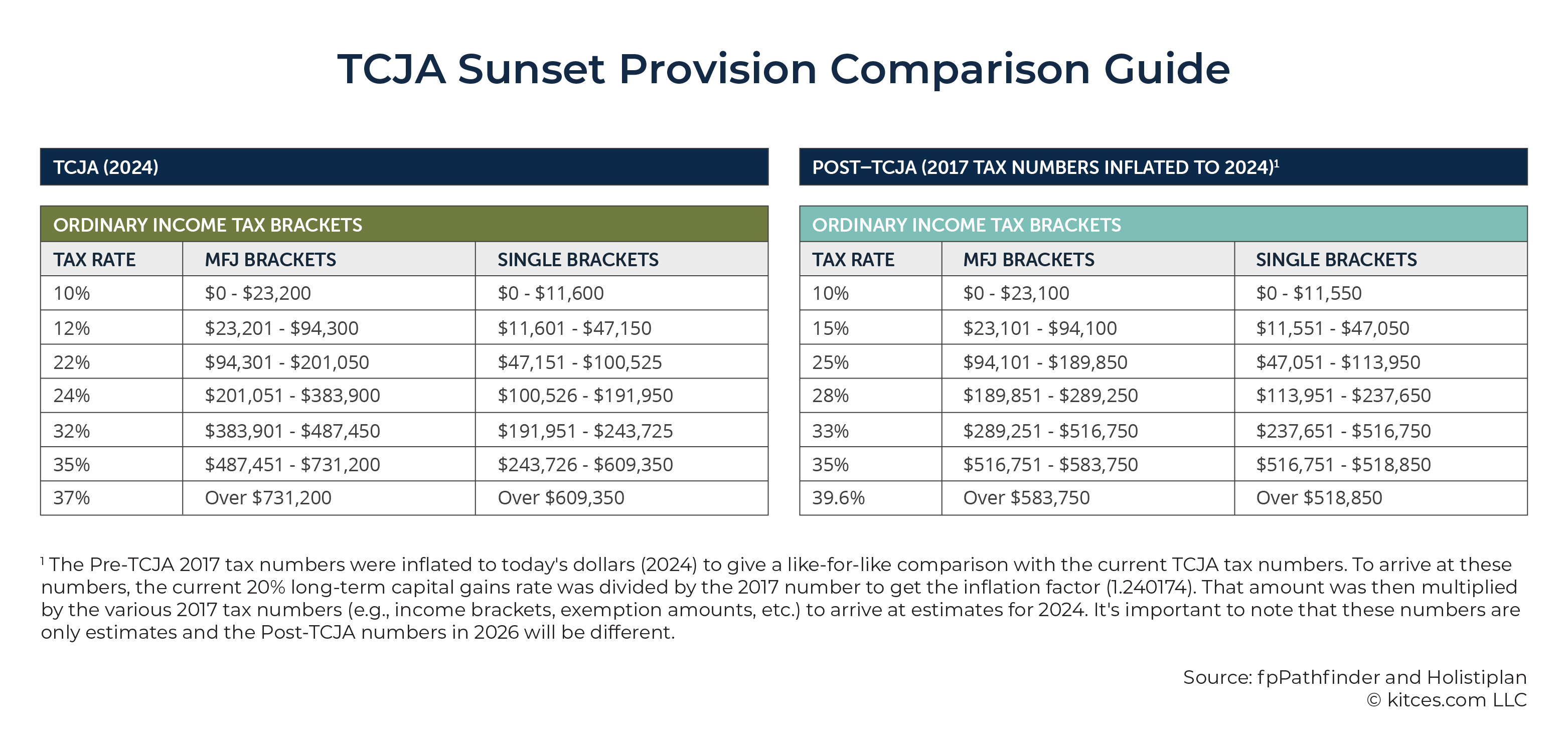

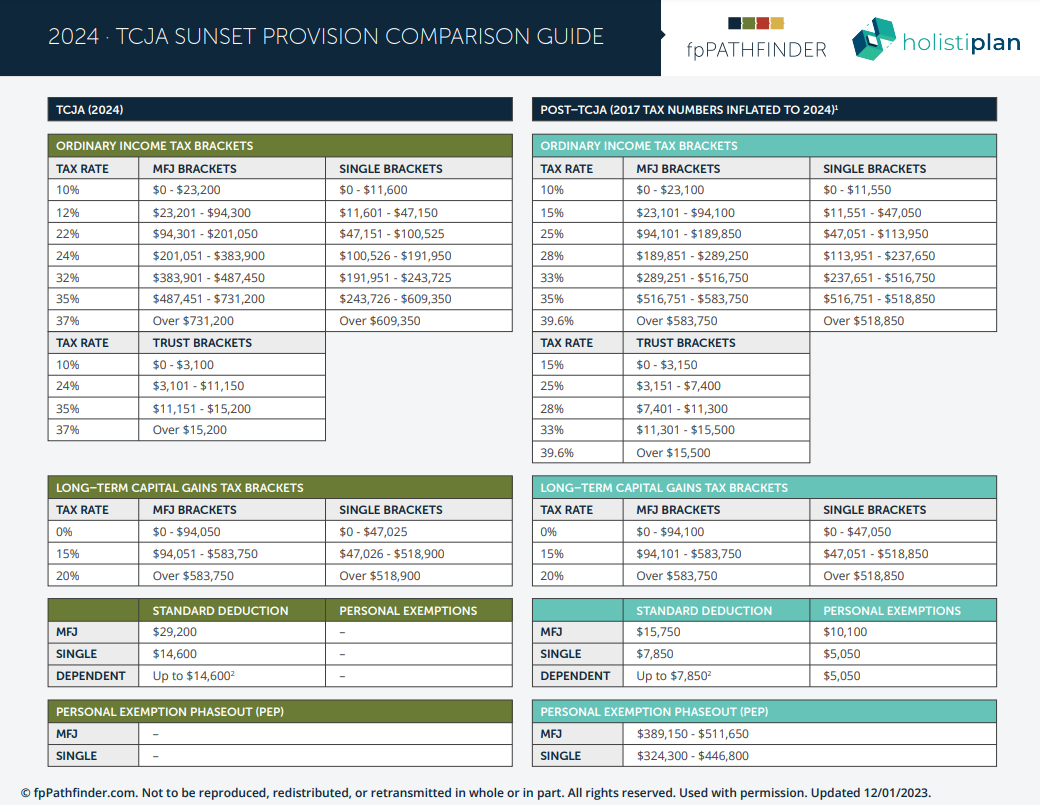

First, it makes sense to look at the change in the tax brackets themselves when TCJA sunsets at the end of 2025. We don't know the exact dollar amounts where each bracket will land in 2026, but by inflating the numbers from 2017 (the last time the pre-TCJA brackets were in effect) to today, it's possible to get an idea of how the post-TCJA bracket structure will compare with today's.

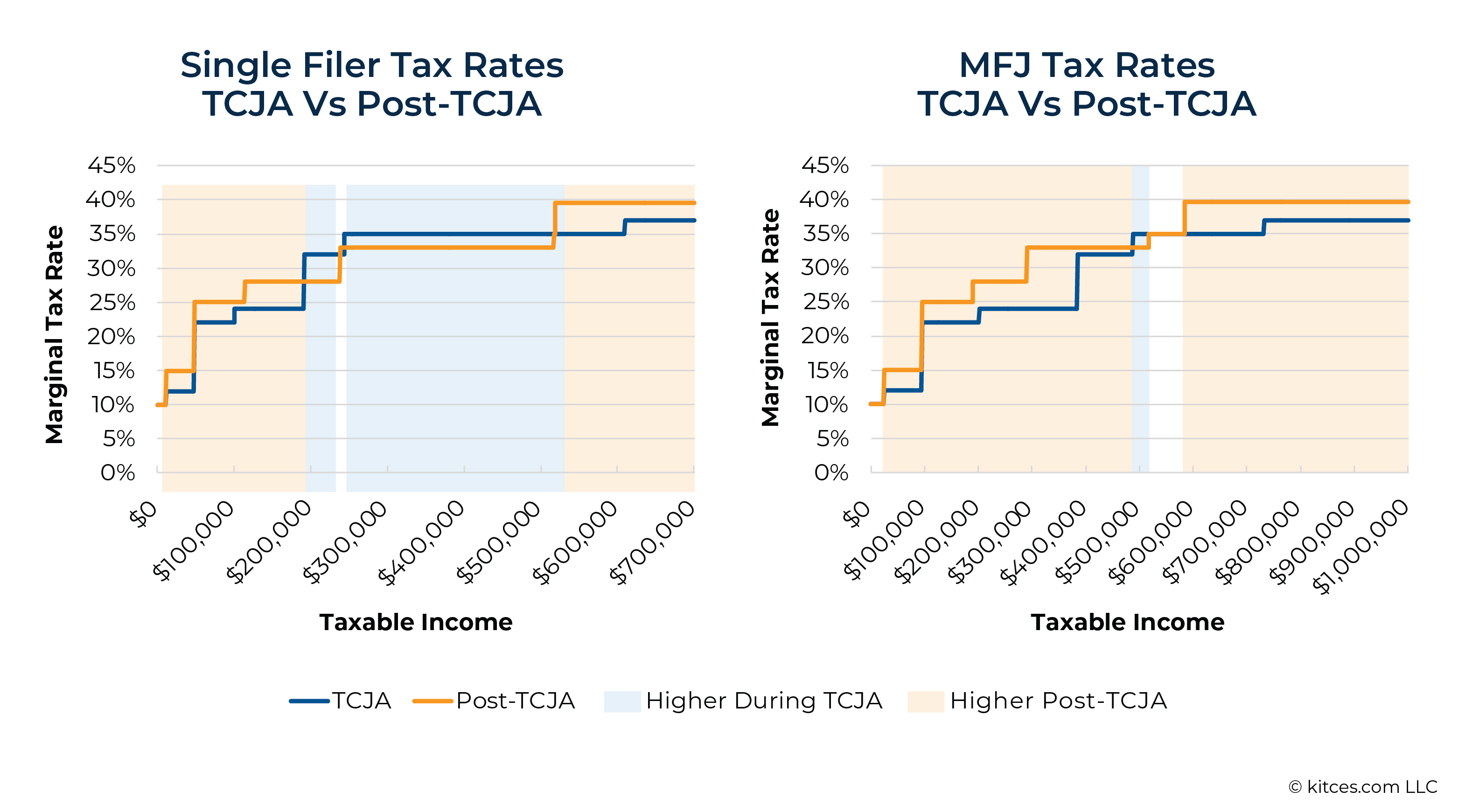

As shown above, today's 7 marginal tax brackets of 10%, 12%, 22%, 24%, 32%, 35%, and 37% will shift to 10%, 15%, 25%, 28%, 33%, 35%, and 39.6% - roughly 1 to 4 percentage points higher for each bracket (except the 10% and 35% brackets, which remain the same). Just as important as the rates themselves, though, are the ranges of income in which each bracket falls, which also differ between the TCJA and post-TCJA versions. As shown below, while the breakpoints between the 10% and 12%/15%, and the 12%/15% and 22%/25% brackets, are roughly the same during and post-TCJA, they begin to diverge significantly in the higher brackets.

What the shift in tax brackets ultimately means is that, for a given level of taxable income, an individual's marginal tax rate might change after TCJA sunsets not only because the tax rates within each bracket have shifted, but also because the brackets themselves have shifted up and down the income spectrum. And, as is clear from the above graphics, taxpayers at many income levels will be in a higher tax bracket post-TCJA, sometimes significantly so (e.g., between $290,250–$383,900 of income in 2024 dollars, where a married couple's tax bracket would rise from 24% to 33%). However, there are also income ranges – particularly for single filers – where the taxpayer will be in a lower bracket after TCJA's sunset. Which means that accelerating income, such as via a Roth conversion, to take advantage of today's 'lower' tax rates could, for many people whose tax rates will actually be lower after TCJA sunsets, result in paying a higher tax rate on that income today!

Accounting For Changes To The Standard Deduction, Itemized Deductions, And Personal Exemptions

The tax brackets shown above are for the marginal tax rate within a given range of taxable income, which is what's left after all adjustments and deductions have been made from the taxpayer's gross income. However, an individual with a given amount of gross income won't necessarily have the same amount of taxable income after TCJA's expiration as they do today, because TCJA made significant changes to what can be deducted from a taxpayer's gross income to calculate their taxable income. Those changes are also scheduled to revert back to their pre-TCJA status after 2025, meaning that an individual's marginal tax rate on a given dollar of gross income will change post-TCJA even beyond the difference in their nominal tax bracket.

There are 4 major changes that will affect how taxpayers' taxable income is calculated:

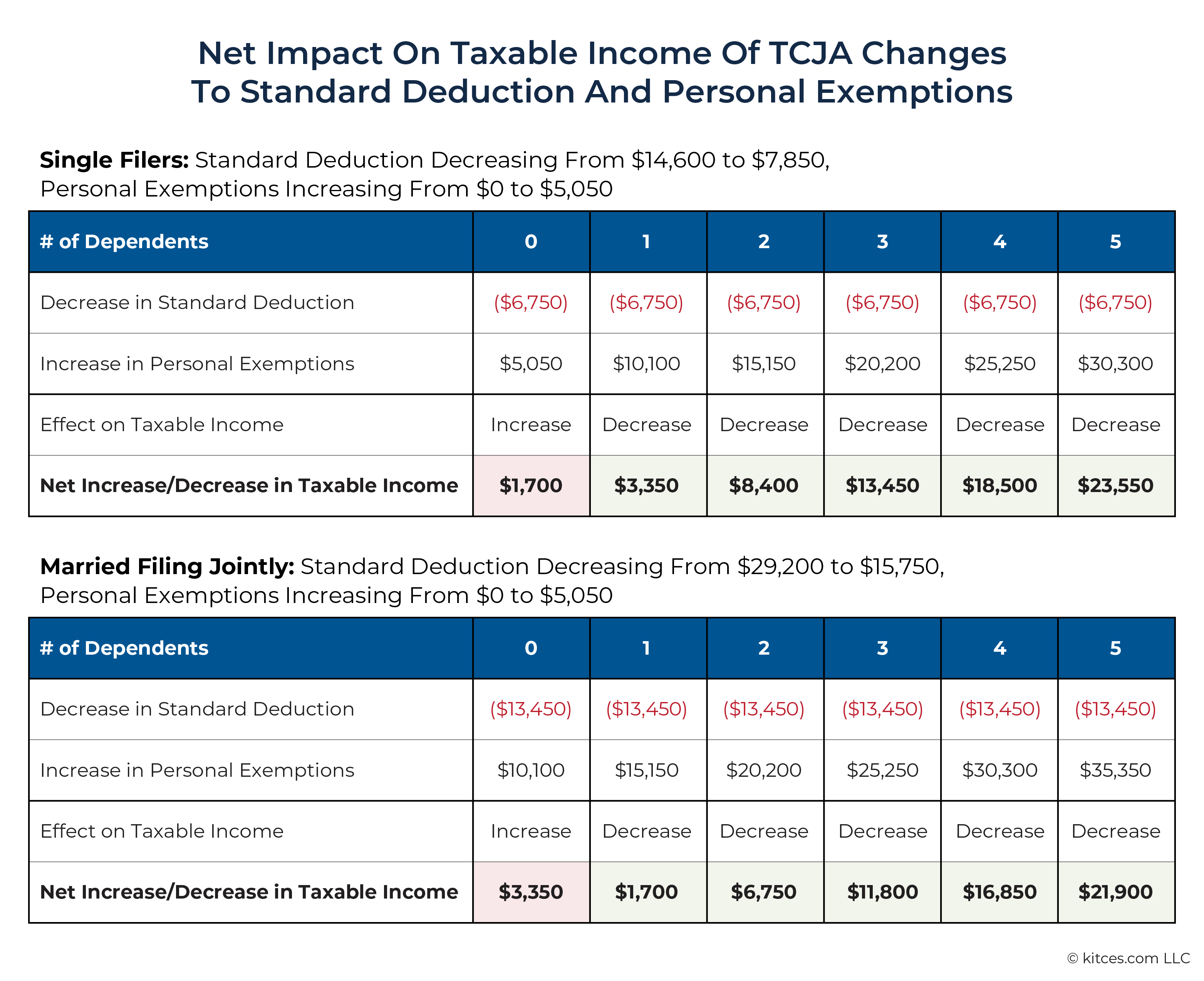

- The standard deduction, which, in 2024, is $14,600 for single filers and $29,200 for MFJ, will be reduced nearly by half, to $7,850 and $15,750, respectively, in 2024 dollars.

- For taxpayers making itemized deductions, 100% of a taxpayer's eligible State And Local Taxes (SALT) payments will be able to be deducted on Schedule A, rather than being limited to $10,000 as they are today, while miscellaneous deductions above 2% of the taxpayer's Adjusted Gross Income (AGI), including unreimbursed employee expenses and investment management expenses (including investment advisory fees deducted from clients' taxable accounts) will also be allowed after being suspended by TCJA. Additionally, TCJA's expiration will raise the cap on home mortgage interest deductibility to the interest on the first $1 million of debt principal (from the current $750,000) and restore the deductibility of home equity indebtedness which was eliminated entirely by TCJA.

- Personal exemptions – which allow a fixed amount of income to be exempted from taxable income per taxpayer or dependent listed on the tax return – will return after being eliminated by TCJA in favor of the higher standard deduction. Prior to TCJA, the personal exemption amount was $4,050 per person; in 2024 dollars, it would likely be around $5,050 (and would increase more by the time TCJA expires in 2026, depending on the inflation rate between now and then).

- The Section 199A deduction for Qualified Business Income (QBI) – which provides a deduction for owners of partnerships, S corporations, and sole proprietorships of up to 20% of the lesser of the taxpayer's QBI or their taxable income – will expire at the end of 2025.

These changes have a few key implications. The first is that many more people will be able to itemize deductions post-TCJA, since not only does the reduced standard deduction create a lower threshold in order to do so, but the removal of the SALT limitation and the revival of miscellaneous itemized deductions also means that many taxpayers – especially those in higher-tax states, who own homes and pay property taxes, and who have professional investment management that draws fees from their taxable portfolios – will simply have more expenses that they'll be able to deduct.

The second is that larger families with at least 2 children will benefit more from TCJA's expiration than smaller families. When TCJA was enacted, it nearly doubled the standard deduction, increasing it by (at the time) $5,500 for single filers and $11,000 for married filing jointly. But it also eliminated personal exemptions, which provided a $4,050 income exemption per taxpayer and dependent. So, for example, a married couple with 2 dependent children taking the standard deduction would have gotten $11,000 as an additional standard deduction in 2018 after the passage of TCJA, but they also would have lost $4,050 × 4 = $16,200 in personal exemptions, meaning that all else being equal, their total taxable income would have risen by $16,200 – $11,000 = $5,200 as a result of TCJA.

As TJCA expires, then, the effects will be reversed: A family with multiple dependent children may see their taxable income decline as a result of the increase in their personal exemptions, adding up to more than the decrease in their standard deduction. However, for filers with few or no dependents, who may have only 1 or 2 personal exemptions to offset the decrease in their standard deduction, the end of TCJA will likely mean greater taxable income. Though, as shown below with estimated numbers in 2024 dollars, taxpayers with 1 or more dependents – both single and married filing jointly – will have a net decrease in taxable income after accounting for the changes to the standard deduction and personal exemptions.

The third major takeaway is that most small business owners of partnerships, S corporations, and sole proprietorships will see a significant increase in taxable income due to the loss of the Sec. 199A deduction for QBI. For many other taxpayers, the net income tax effects of TCJA's sunset might be marginal due to offsetting increases and decreases in deductions, exemptions, and tax rates (like the reduced standard deduction being canceled out by the return of personal exemptions). But many owners of pass-through businesses who saw their Federal income tax go down during the TCJA years will need to prepare to pay higher taxes after the law expires – presuming, of course, it isn't extended. (Although the idea behind the Sec. 199A deduction was to create relative parity with TCJA's reduction of C corporation tax rates from 35% to 21%, which is one of the few provisions of TCJA that isn't set to expire after 2025 – meaning there's a somewhat legitimate argument for extending the Sec. 199A deduction for as long as C corporation tax rates remain where they are. But that doesn't mean it actually will be extended.)

Return Of Income-Based Phaseouts For Itemized Deductions And Personal Exemptions

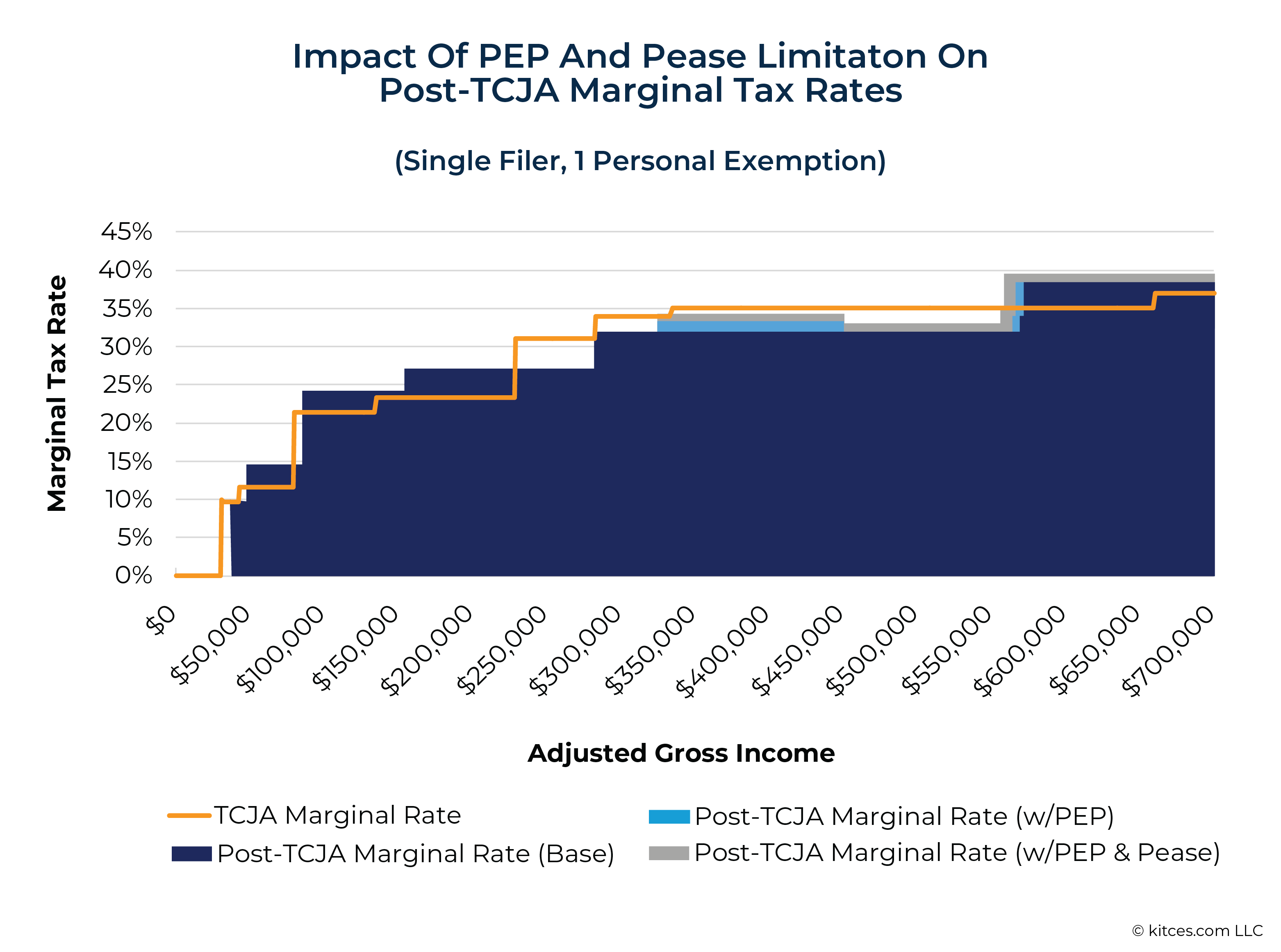

Prior to TCJA, taxpayers who exceeded certain AGI thresholds became subject to limitations on the amount of personal exemptions and/or itemized deductions they could claim. Obviously, since there haven't been personal exemptions under TCJA, taxpayers haven't had to worry about a personal exemption phaseout, but the law also did away with the so-called "Pease limitation", which reduced the amount of itemized deductions a taxpayer could claim if they crossed the threshold. When TCJA sunsets, those limitations will both return, effectively creating an additional surtax on income above the threshold (in estimated 2024 dollars) of $324,300 for single filers and $389,150 for MFJ.

As a refresher, the Personal Exemption Phaseout (PEP) reduces each personal exemption by 2% for every $2,500 of AGI above the threshold. By the math of the phaseout, then, all personal exemptions are completely phased out after reaching $122,501 in income over the threshold.

Example 1: Brittany is a single tax filer with $425,000 of adjusted gross income. Assume that TCJA expires as planned after 2025, meaning that the Personal Exemption Phaseout is back in effect in 2026, the personal exemption amount is $5,010, and the PEP threshold for single filers that year is $324,300.

Brittany's income of $425,000 puts her at $100,700 above the $324,300 PEP threshold, which equates to 41 units of $2,500 ($100,700 ÷ $2,500 = 40.28, rounded up to 41). That means that her personal exemption is reduced by (41 × 2%) × $5,010 = $4,108, to $5,010 − $4,108 = $902.

The Pease Limitation uses the same AGI threshold as the Personal Exemption Phaseout, reducing a taxpayer's allowable itemized deductions by 3% of the amount by which their AGI exceeds the threshold (with a maximum 80% reduction in itemized deductions).

Example 2: Brittany, from the example above, pays $20,000 in mortgage interest in 2026 and also itemizes her deductions. Because her income exceeds the Pease threshold by $100,700, her allowable itemized deduction for mortgage interest is reduced by $100,700 × 3% = $3,021, to $20,000 − $3,021 = $16,979.

The math works out so that the PEP equates to an approximately 1.3% surtax per exemption on any additional income within the phaseout range, while the Pease limitation adds an additional 1% surtax on all income above the threshold until the maximum 80% reduction in itemized deductions has been reached.

After TCJA's expiration, then, the net effect of the return of the PEP and Pease limitation will be to further increase marginal tax rates for households with income over the thresholds (and, in the case of the Pease limitation, for households that itemize deductions) – with the greatest impact being on higher-income families with multiple dependents, since the PEP surtax amounts to 1.3% for each exemption, on top of the additional surtax imposed by the Pease limitation.

As shown below, for a hypothetical case with a single filer paying a flat 3% state income tax rate with an additional $30,000 in other itemized deductions, adjusting for the PEP and Pease surtaxes narrows the gap between pre- and post-TCJA expiration marginal rates, such that between $334,000 and $449,000 of AGI (in 2024 dollars) the taxpayer would effectively pay a marginal rate of 34% after TCJA's expiration versus 35% before.

Still, however, even adjusting for the PEP and Pease limitation, the person in this scenario would pay a lower marginal rate after TCJA's expiration on all income between $229,000 and $558,000 of AGI (again in 2024 dollars) compared with what they would be paying today.

At the same time, as the next graphic shows, in the case of married couples filing jointly, adjusting for the PEP and Pease limitation increases the disparity between pre- and post-TCJA expiration tax rates (where the post-TCJA rates for couples within the PEP phaseout range rise even more as a result of PEP).

Again, using an example of a 3% state tax rate plus $30,000 of other itemized deductions, a married couple with 2 exemptions earning between around $390,000 and $514,000 in 2014 dollars will pay a 36% marginal tax rate on those dollars after TCJA's expiration, versus just 22%–24% today. If there were more exemptions (e.g., because of additional dependents), the effect would be magnified even further, with the marginal tax rate within the PEP phaseout range rising by another 1.3% for each additional personal exemption.

Impact Of Losing The Sec. 199A (QBI) Deduction

In addition to the changes affecting the standard deduction, itemized deductions, and personal exemptions, the end of TCJA will also have a significant impact on household tax rates with the phaseout of the Sec. 199A deduction on Qualified Business Income (QBI). Currently, owners of pass-through businesses such as partnerships, S corporations, and sole proprietorships can receive a deduction equal to 20% of the lesser of their total QBI or their taxable income (before taking the deduction into account).

However, for certain business owners – most notably, for owners of Specified Service Trade or Businesses (SSTBs) such as consulting firms, law offices, or investment advisory firms – that deduction phases out for households whose taxable income in 2024 (before accounting for the QBI deduction) exceeds $191,950 for single filers and $383,900 for MFJ, with the deduction being eliminated entirely for SSTB owners with taxable income over $241,950 for single filers and $484,900 for MFJ. Owners of non-SSTB businesses, by contrast, have no income-based phaseouts of the amount of Sec. 199A deduction they can take and are only limited to the greater of either 50% of the total W-2 wages of their business, or the sum of 25% of W-2 wages plus 2.5% of the unadjusted basis of all qualified property in the business.

Since the Sec. 199A deduction is set to expire with the rest of TCJA after 2025, many business owners currently benefitting from the QBI deduction will, in most cases, pay a higher tax on the same amount of income in 2026 and beyond, assuming the current law doesn't get extended. With the caveat that, for SSTB owners whose income exceeds the threshold above which the deduction is eliminated, the sunset of the Sec. 199A deduction won't have any impact in and of itself, since those SSTB owners aren't eligible for any deduction in the first place.

In most cases, when someone is expected to pay higher tax rates in the future, it can be beneficial for them to accelerate income by recognizing income today at lower tax rates in order to avoid recognizing and paying higher tax rates on it later on, or to defer deductions until future years when the deductions would have a greater impact. Business owners who currently take the Sec. 199A deduction might accelerate some income so it's recognized in 2024 and 2025 rather than waiting until 2026 when the 20% deduction for QBI is no longer available. And for those who are completely phased out of the deduction, it might still make sense to accelerate some income since their marginal tax rate may increase even without regard for the Sec. 199A deduction.

However, it's also worth noting that for households in or near the phaseout range for the Sec. 199A deduction for SSTBs, the math on accelerating income gets much less favorable. That's because any additional income earned within the phaseout range reduces the allowable deduction, such that each $1 earned within the phaseout range creates more than $1 of taxable income. Which means that the effective marginal tax rate on income earned within the SSTB phaseout range, particularly for taxpayers with large amounts of QBI, is much higher than the individual's nominal tax bracket.

At the extreme, imagine a business owner whose income consists solely of QBI from an SSTB. Below the phaseout range, their income is taxed at lower rates pre-TCJA sunset compared to post-TCJA sunset because they would be able to deduct 20% of their total taxable income due to the Sec. 199A deduction.

However, once an SSTB owner reaches the phaseout range, that 20% deduction begins to shrink towards zero – not just on income earned above the phaseout threshold, but on all QBI. Which means that additional dollars earned within the SSTB phaseout range are taxed at progressively higher marginal rates, ranging from 37% at the bottom of the phaseout range all the way up to 63% just before the deduction is phased out entirely. And so for an SSTB owner with income within that phaseout range, recognizing additional income today will result in those dollars being taxed at a much higher rate than they would be if they weren't recognized until TCJA's expiration.

Meanwhile, for an SSTB owner whose income is entirely above the phaseout range (and has no more deduction to be phased out of), their marginal tax rate on additional income is effectively the same as someone with no QBI at all. Which means that their marginal tax rate after the TCJA sunset would be slightly higher (for those in the post-TCJA 39.6% tax bracket), slightly lower (for those in the post-TCJA 33% bracket), or about the same (for those in the post-TJCA 35% bracket) than their pre-sunset rate.

For an owner of a non-SSTB pass-through business who isn't subject to the SSTB phaseout and can claim the full Sec. 199A deduction no matter their income level (so long as they meet the "wage and property" limitations as described earlier), they will almost assuredly have a higher marginal tax rate after TCJA sunsets in 2025, regardless of their actual level of income.

As shown below, then, there are effectively 3 income "zones" for SSTB owners that will dictate whether it makes sense to accelerate or defer income prior to TCJA's expiration. For those below the SSTB phaseout threshold who will have a higher marginal rate after the TCJA sunset, it might be better to accelerate income. For those within the phaseout zone whose marginal rate will be significantly higher before the sunset, it might be better to defer (or conversely, to accelerate any business-related deductions). And for those whose income has already phased them out of the Sec. 199A deduction, it could be either – the decision will likely come down to their income, filing status, and what other deductions they might have available. (For non-SSTB owners, however, they're more likely to be better off accelerating income wherever possible no matter their income level.)

The takeaway, then, is that for business owners currently benefitting from the Sec. 199A deduction, it might make the most sense to recognize extra income while TCJA is in effect if the business owner either (1) doesn't own an SSTB subject to income-based phaseouts; or (2) is an SSTB owner, but isn't within the phaseout range of $191,950–$241,950 for single filers or $383,900–$483,900 for MFJ where accelerating income would drastically increase the tax rate paid on those dollars. For example, business owners can invoice clients before the end of 2025 where possible, defer expenses or opt for a longer depreciation period on business equipment, or make Roth retirement contributions rather than contribute to pre-tax retirement plans (which themselves effectively serve to reduce the amount of Sec. 199A deduction that a small business owner can take). Otherwise, it would make more sense not to accelerate any income, even when the household's nominal tax bracket is lower today than it will be after TCJA's expiration.

Planning For Tax Bracket Shifts After TCJA's Expiration

It bears repeating that all of the above numbers are in 2024 dollars, and we don't know yet exactly what the tax bracket breakpoints, personal exemptions, and PEP and Pease limitation thresholds will be in 2026 after TCJA expires. But even just using estimates is enough to at least give an idea of the income ranges of households that (depending on their filing status, amount of deductions or exemptions, and/or access to the Sec. 199A deduction on qualified business income) may be poised to see a significant increase – or in some cases, a decrease – in the tax rate on any additional dollars of income starting in 2026.

Based on the major personal income tax changes described above, advisors can focus on several key income ranges where accelerating (or delaying) income will have the most impact after TCJA expires. The graphic below doesn't include all of the income ranges where there will be a difference between a person's pre- and post-sunset marginal tax rates, but it does show where the biggest differences will occur that may be worth taking action on should the TCJA sunset go forward as scheduled.

Analyzing The Costs And Benefits Of Taking Action Amid Political Uncertainty

It's worth recalling here that there's no guarantee that TCJA will actually sunset and that any number of changes can happen before the end of 2025. And so it can be beneficial to consider not only the potential benefit of taking action today, assuming that the law expires as planned, but also the potential cost of doing so if the law is extended, either as it currently exists or in some altered state. In other words, how much is at risk in gambling that the law will expire, and what is the potential upside if that gamble pays off?

In the case of accelerating or delaying income, the downsides of taking action now are fairly limited. Because while there is plenty to be gained from taking action before the law expires, in the form of saving 5%–10% or more in taxes on the income being accelerated or delayed (and there may even be some benefit to taking action in 2024, e.g., taking advantage of 2 years of Roth conversions to recognize as much income as possible at lower rates), the most likely downside if TCJA is extended is that today's tax rates are simply extended indefinitely. In other words, the income recognized today would be taxed at the same rate in any year going forward, so while there may not have been much value gained in accelerating it, there wouldn't be much value lost either.

The key point, however, is that although using the income ranges above can help advisors broadly identify which clients may be good candidates to accelerate income, such as in the form of a Roth conversion, the fact remains that there are so many different factors at play around what someone's tax situation will look like before and after TCJA's sunset. Between the realignment of the tax brackets themselves, the changes to the standard deduction and itemized deductions, the reinstatement of personal exemptions (and of the Personal Exemption Phaseout and Pease Limitation), and the end of the Sec. 199A deduction for QBI, the actual value (or lack thereof) of accelerating income really comes down to each client's individual circumstances. Some clients may have remarkably similar tax situations before and after TCJA expires, with tax increases in some areas being largely offset by decreases in others, while for other clients, the law's sunset at the end of 2025 will mark a dramatic shift in planning for and paying taxes.

It may not be necessary to make a detailed before-and-after tax comparison for each and every client, but for clients in the income ranges above, it's very possible that running the numbers will reveal opportunities to save significant tax dollars by timing the recognition of new income to occur before or after the TCJA sunset date to the extent that it's possible. Which can be done either by having the client's CPA compare pre- and post-TCJA expiration scenarios on their own tax software or, in many cases, by the advisor themselves using tax projection tools like Holistiplan and FP Alpha that have already begun building TCJA sunset planning features into their software.

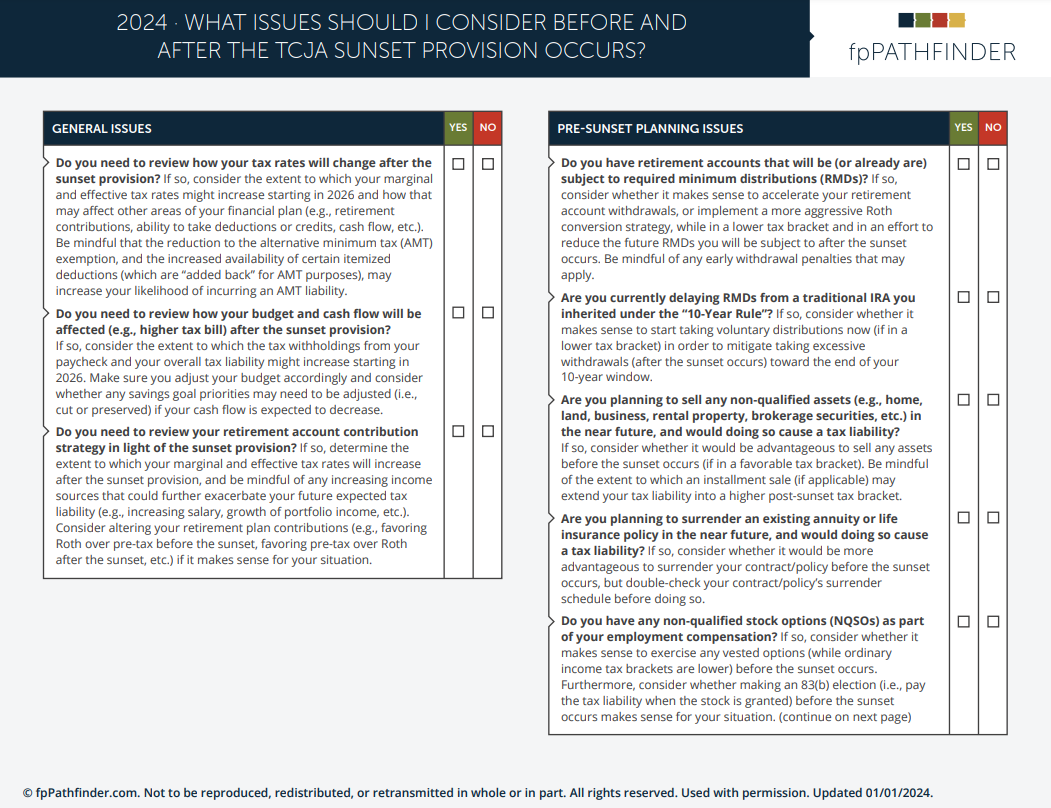

Ultimately, as the news and financial media increasingly pick up the TCJA sunset as a topic around the election and clients develop their own questions that they bring into meetings, it will become increasingly valuable for advisors to get familiar with the changes that the law's expiration will trigger and what they mean for clients in different circumstances. The TCJA Sunset Provision Comparison Guide, put together by fpPathfinder and Holistiplan, gives a high-level summary of the changes, with estimated post-TCJA numbers stated in 2024 dollars, which can help advisors give their clients a sense of what they can expect in the event that TCJA's sunset happens as planned.

Leave a Reply