Executive Summary

While qualified plan participants are generally required to begin taking distributions April 1 of the year following the year the plan participant turns 70 ½, the "still-working" exception delays the RBD to April 1 of the year following the year the employee retires. The motivations behind the still-working exception are simple enough (Congress anticipated that some workers would continue working beyond age 70 ½ and did not want to force these participants to begin taking distributions), however the reality is that the provision itself is surprisingly complex, containing many layers of rules that influence one another and make the determination of whether an individual is "still-working" more difficult than many would expect.

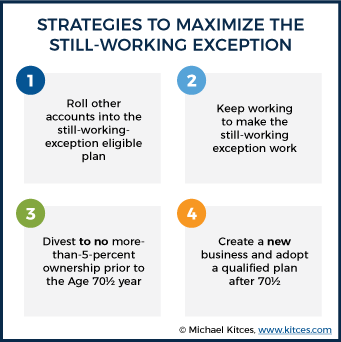

In this guest post, Jeffrey Levine of BluePrint Wealth Alliance, and our Director of Advisor Education for Kitces.com, takes a deep dive into the still-working exception, examining how an individual is (or is not) determined to be "still-working", as well as the planning strategies that arise from the exception, such as rolling qualified assets into a still-working exception eligible plan, divesting more than 5% ownership of a company prior to age 70 ½, creating a new business after age 70 ½, and even just making sure the requirements are met to qualify for the still-working exception!

To the surprise of many, defining precisely what it means to be "still working" (e.g., 1 hour per week, 10 hours, 20 hours?) is not something that the IRS has done. However, the general interpretation based on a plain reading of the law is that, as long as the employer still considers an individual employed, that person is “still employed” for the purpose of the still-working exception (even if the ongoing work is of a relatively limited nature). However, this determination is further complicated by the fact that an employee must be employed throughout the entire year to qualify for the exception and delay RMDs past their 70 ½ year, which is defined as not having retired at any point during the year, including December 31st! So, if an individual worked every day of the year (including a full work day on December 31st), but retired on December 31st (i.e., did not come back to work at any time in the next year), then the individual would be deemed retired in that year and would not be eligible for the still-working exception during that year.

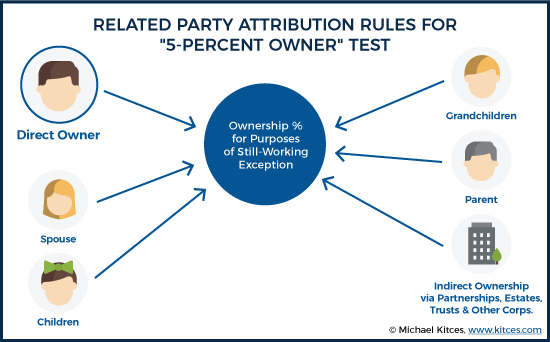

Another complication with determining whether an individual is "still working" is the exclusion of the rule for 5% owners of a business. One point of confusion is that 5% owners are not considered "5% owners" for the sake of this rule. Instead, owners must own more than 5% in order to be considered a 5% owner. A second point of confusion is that ownership according to the 5% ownership rule includes indirect ownership of stock owned by a spouse, children, grandchildren, and parents (though not siblings, cousins, aunts/uncles, and nieces/nephews). Further, the still-working exception is based on a one-time test of ownership in the plan year ending in the year an employee turns 70 ½, which actually means that those who own an increasing amount of a company after reaching age 70 ½ can own more than 5% and be considered less than 5% owners (or may own less but still are considered more than 5% owners).

Fortunately, this complexity does create planning opportunities which individuals can use to reduce (or at least delay) their tax bill. In particular, individuals may want to consider rolling other qualified into still-working exception eligible plans (as only an account through an eligible employer receives an exception from taking a distribution), divesting more than 5% ownership prior to age 70 ½ (as the test is only applied at this age), creating a new business and adopting a qualified plan after age ½ (as the new business would not have been around when an individual reached age 70 ½), or just making sure that the requirements to receive the still-working exception are met (as despite the popularity of retiring on December 31st, it may be beneficial to work at least one day into a new year).

Ultimately, the key point is to acknowledge that the still-working exception is not as straight-forward as is often believed. There is a lot of complexity in the rules surrounding the still-working exception, yet, at the same time, a lot of opportunity for tax planning as well (at least for those who have the luxury of not needing their retirement funds at age 70 ½ and who can continue to defer spending into the future)!

Planning With the “Still Working Exception”

IRAs, 401(k)s and other tax-deferred accounts have long been key tools in the planning arsenal, and offer a number of valuable tax benefits that can help investors build wealth overtime on a tax-efficient basis. The primary purpose of these accounts is to allow taxpayers to put aside funds during their working years on a tax-favored basis, to use later in retirement.

For a variety of reasons, many individuals end up “tapping into” their retirement accounts prior to retirement. Others wait until retirement to begin taking distributions from such accounts. Some people, however, are lucky enough to have pensions, other sources of income, or enough saved in other accounts not to need the money in their retirement accounts… ever. Nevertheless, the law generally doesn’t allow an individual’s retirement accounts to escape the wrath of taxation forever. Instead, there is generally a drop-dead date by when distributions must begin, with income taxes subsequently paid. That date is given the formal name “The Required Beginning Date”, or RBD for short, and the distributions that occur thereafter are called “Required Minimum Distributions” (or RMDs).

Under IRC Section 408, and more specifically Treasury Regulation 1.408-8, Q&A 3, the required beginning date for IRAs is April 1 of the calendar year after the calendar year in which the IRA owner turns 70 ½. This is the RBD for all IRAs (other than Roth IRAs, which have no RMDs during the owners lifetime), including SEP IRAs and SIMPLE IRAs. Thus, regardless of a SEP/SIMPLE IRA owner’s employment status as of April 1 of the year following the year they turn 70 ½, they must begin taking RMDs from those accounts… even if they are still making and/or receiving ongoing contributions to those accounts because they are still working!

Similarly, under IRC Section 401(a)(9)(C)(i)(I), the required beginning date for distributions from qualified plans is also generally April 1 of the year following the year the plan participant turns 70 ½.

An exception, however, is provided immediately afterwards in IRC Section 401(a)(9)(C)(i)(II), specifically for qualified plans (e.g., 401(k) plans, profit-sharing plans, etc.), which delays the RBD to April 1 of the year following the year the employee retires (if that date is later than the April-1-of-the-year-following-the-year-the-participant-turns-70 ½ default date). This provision is commonly known as the “still-working exception,” and is a common tool used by plan participants to delay the onset of RMDs in 401(k) and other employer qualified plans.

The origins of the still-working exception are simple to understand. Congress created qualified plans to help employees save for retirement during their working years, so that they would be able to enjoy a more comfortable retirement (and, perhaps, not need additional governmental assistance). Although most people are retired by 70 ½, Congress did contemplate that some individuals would continue working beyond that age, and thus, wanted to allow them to continue to benefit from the tax-deferral offered by their employer’s 401(k), or similar plan, throughout their ongoing employment years.

Yet while the origins of the still-working exception are simple to understand, the provision itself is surprisingly complex. Indeed, the still-working exception is much like the proverbial onion, where you pull back one layer, only to be met with another… and another… and another.

What is the Definition of “Still Working”?

Let’s start by examining what should be the simplest of all matters to decide: how to determine if someone is “still working” in the first place?

Obviously, to still be working, one must be employed… but what if that work is part-time? Is that good enough? What if someone only works 12 hours per week, per month, or even per year!?

Interestingly, this is one question that the IRS has never chosen to address in any meaningful manner. A plain reading of the law, however, seems to indicate that any level of continuous employment is good enough. Under IRC Section 401(a)(9)(C)(i)(II), the RBD is delayed until April 1 of the year after “the calendar year in which the employee retires.” There is no mention of any requirement related to full-time employment, nor is there any indication of a minimum-hours-worked or similar requirement. Thus, the general interpretation is that, as long as the employer still considers an individual employed, that person is “still employed” for the purpose of this provision (even if the ongoing work is of a relatively limited nature).

December 31st Measuring Date For Still-Working Exception

With respect to the “still working” requirement of the still-working exception, one issue that routinely surprises both advisors and clients, is the requirement that an employee be employed throughout the entire year to qualify for the exception and delay RMDs past their 70 ½ year. The confusion here, primarily revolves around a single day: December 31st.

For a variety of reasons, some psychological, and others financial, December 31st is a popular day to retire. Unfortunately though, retiring on December 31st, even after working a “regular” shift for the day, is not enough to allow someone to qualify for the still-working exception! The IRS’s position is that if someone retires at any point before the stroke of midnight on New Year’s Eve, they have retired on December 31st, and thus, will have to take their first RMD for that (retirement) year.

Example 1. Bob is 75 years old and works for ABC Builders, Inc. He meets all the criteria of the still-working exception, and has avoided taking RMDs from his ABC Builders, Inc. 401(k) plan since turning 70 ½. Bob, however, has recently decided that it’s time to hang up the hard hat, and is planning to retire at the end of the year.

Now imagine that, as the year comes to an end, Bob decides to make it a “clean break” at the end of the 2018 (this year). On December 31, 2018, Bob heads in for his last day of work and puts in his typical 9-to-5 shift. As he finishes up his very last day of work, Bob shakes hands with his now-former colleagues, exchanges pleasantries… and ensures himself of the need to take an RMD for 2018!

Despite the fact that Bob worked a full shift on December 31st and, if he had remained employed, would not have needed to return to work until the following calendar year (the next day of work being January 1, 2019), Bob is still treated as having retired in 2018, and not being employed throughout the full year. Thus, the still-working exception does not apply to Bob for 2018. Which means he’ll only have 3 more months (until April 1st of 2019) to complete that first RMD (and he’ll have a second RMD due for 2019 as well!).

If, on the other hand, Bob’s employer had asked him to come in on January 1, 2019 for a few hours in order to help finish dealing with a few loose ends, Bob’s retirement would now occur in 2019. Thus, by working the single extra day, Bob would have availed himself of the use of the still working exception for 2018, and would be able to delay RMDs for the entire additional year.

The Still-Working Exception is Employer (And Employer-Plan) Specific

It’s important for advisors to understand that, while the still-working exception can allow a working 70 ½ (or older)-year-old to delay required minimum distributions until the year he/she separates from service, the exception only applies to the plan of the company they are still working for at that time.

Thus, if the employee has assets held in other plans of other (former) employers from which they have already separated from service, RMDs must still be taken from those plans, and the still-working exception does not apply to/for them.

Example 2. Sally is a 73-year-old engineer who is currently employed with Aerospace Consultants, Inc. She has built up a sizable balance in the Aerospace Consultants, Inc. plan, but also has two other 401(k) accounts from previous employers with significant balances.

Assuming Sally meets all the other rules for taking advantage of the still-working exception, she can delay taking RMDs from her Aerospace Consultants, Inc. plan only. She must, however, take required minimum distributions from both of her other 401(k)s (each of which must be drawn from the respective 401(k) plans, because RMDs from qualified plans cannot be aggregated across the plans).

It’s also important to note that, while the still-working exception is generally available in most plans, plan specific language can render it irrelevant. For instance, while not many plans do, there is nothing in the law to prevent a plan for stating that all participants must begin distributions by the year they turn 70 ½, regardless of their current employment status. Therefore, advisors should always double check a client’s plan document, or summary plan description, to ensure availability of the still-working exception, if it is intended to be used.

Prohibition Of Still-Working Exception for 5-Percent Owners

Occasionally, the language of the tax code is straightforward, understandable, and logical. More often than not, however, the tax code is a complex mess that results in a wild goose chase when trying to make heads or tails of a particular provision, because of how tax code provisions get layered on top of each other as Congress adds more rules over time. And nowhere may the wild-goose-chase-esque nature of the tax code be on greater display than when it comes to the still-working exception.

When Congress originally wrote this provision in the law, they were mindful of the fact that, as an owner of a business, it would be relatively easy to keep yourself employed, even if at only a minimal level, in order to potentially delay required minimum distributions indefinitely. As such, Congress took steps to minimize this potential abuse by restricting the availability of the exception “in the case of an employee who is a 5-percent owner.” Let the wild goose chase begin…

5% Owners of Companies are NOT “5-Percent Owners”!

At first glance, you would think it would be pretty easy to determine who is a 5% owner of a business, and who is not. IRC Section 401(a)(9)(C)(ii)(I) of the tax code tells us that a “5-percent owner” of a business is not eligible to use the still working exception, but then directs us to IRC Section 416, the Internal Revenue Code section covering the special rules for top-heavy plans, to define a “5-percent owner”.

And wouldn’t you know it, under IRC Section 416, a person who owns exactly five percent of a business is not considered a “5-percent owner” for purposes of the still-working exception. Instead, a “5-percent owner” is defined as someone who owns more than 5% of a business.

That may seem like a matter of semantics, but it’s not. You would be surprised at how many people happen to own exactly 5% of a business. Think about it for a moment… suppose you been working somewhere for many years, and your employer comes to you and tells you that they want to make you a part-owner of the business with them. What if they told you they were going to give you 4% of the business? There’s certainly nothing wrong with that number, but for whatever reason, if you ask many people, it just doesn’t feel “right.” On the other hand, if that same employer came to you and told you that they were going to give you 5% of the business, aside from what that 1% is actually worth, it sounds much better, doesn’t it? And so with that in mind, it’s important not to discount the number of people who actually do qualify for the still-working exception as exactly five percent owners, despite the provisions prohibition on “5-percent owners”!

Of course, in other situations, such as when someone owns 25% of a company, it’s quite clear that they are a “5-percent owner”. Similarly, sole proprietors with Schedule C businesses are always considered “5-percent owners” because, by definition, they always own 100% of the business!

Family and Related Business Attribution Rules Apply

We just saw that an exactly 5% owner of a business is not a “5-percent owner” for purposes of the still-working exception, so surely someone who owns only two percent of the same business cannot be considered a “5-percent owner”, right? Wrong! Because the wild goose chase continues!

IRC Section 416 refers us to IRC Section 318 in order to determine an individual’s ownership percentage for purposes of the still-working exception. And IRC Section 318 covers constructive ownership of stock, requiring that a person’s actual, direct ownership of a corporation be added together with the indirect ownership of stock owned by a spouse, children, grandchildren, and parents (though siblings, cousins, aunts/uncles, and nieces/nephews, are not included), as well as stock owned indirectly via partnerships, estates, trusts, and other corporations. As such, even if an employee owns 5% or less of a company themselves, they may fail to be eligible for the still-working exception when the ownership percentages of related persons and/or entities are added together.

Example 3. Roger is 69 years old and owns 100% of Local Hardware Store, Inc., which sponsors a 401(k) plan for its employees (including Roger). After nearly 50 years of blood, sweat, and tears, Roger has decided to step back from the business to spend more time traveling with his wife, and enjoying their grandchildren. Roger intends to transfer his shares equally to his two daughters, Eve and Ann, who work with him in the store.

Now suppose that Roger completes the transfer of his ownership of Local Hardware Store, Inc., as planned, prior to the year in which he turns 70 ½. Roger, however, is not willing to step away from the store completely, and still plans to come in 10 to 15 hours a week to help see his daughter through a successful transition.

Fast forward a few years… Roger has just turned 70 ½ and is still working his 10 to 15 hours per week. Roger enjoys his semi-retirement so much, that he can’t see himself ever fully retiring. So, since Roger is still employed, and owns 0% of the company for which he works, can Roger avoid taking a required minimum distribution from his Local Hardware Store, Inc. 401(k) plan account?

No!!! Roger must take a required minimum distribution from his Local Hardware Store, Inc. 401(k) (or face the draconian failure-to-take-an-RMD penalty) because his daughters’ ownership percentages must be added back to that of his own to determine whether he’s at or below the 5% ownership threshold. Thus, for purposes of the still-working exception, Roger is treated as though he still owns 100% of Local Hardware Store Inc. (because 100% is owned by his daughters), and is thus considered a (more than) ”5-percent owner”.

Notably, the same result above would apply if, for instance, a husband and wife each own 3% of a business (as their combined ownership with family attribution would be 6%), as it would for a person who owns four percent of a business directly, but who owns another two percent of the business indirectly via a trust. In both situations, no single person actually owns more than 5% of the business, but in each case, they would be considered a “5-percent owner” when it comes to the still-working exception thanks to the family attribution rules.

Defining "Ownership" for Purposes of the Still-Working Exception

Of course, even if we know whose ownership percentages must be aggregated together when considering whether an employee is a "5-percent owner", we still need to know what, precisely, defines ownership for any of those persons and/or entities to begin with! And unfortunately, the term “ownership” is somewhat fungible and can mean different things in different situations. Thankfully, IRC Section 416 does not leave us guessing.

Under IRC Section 416, if the entity in question is a corporation, then a “5-percent owner” is deemed to be anyone who owns either 5% of the outstanding stock of the corporation, or who possesses enough stock to give them more than 5% of the total combined voting power of the corporation.

On the other hand, if the entity in question is a partnership, or other business that is not a corporation, then ownership is determined based on ownership of profit, as well as ownership of capital of the business. Thus, if a partner in a partnership is entitled to more than 5% of the partnerships profit, or more than 5% of the partnerships capital (i.e., it is the greater of the two), they are considered a “5-percent owner” for purposes of the still-working exception.

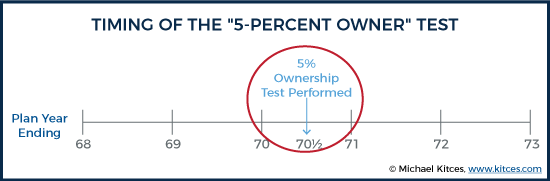

Satisfying The Still-Working Exception Is A One-Time Test

A common fallacy among both advisors, and their clients, is that the still-working exception’s five-percent-ownership test is re-evaluated every year to determine if an RMD will be due for that year. That is not the case, however.

Rather, the 5% ownership test is performed only a single time, at the plan year ending in the calendar year in which the employee reaches 70 ½. If an employee is considered a “5-percent owner” at that time, they will always be considered a “5-percent owner” of that business and will never be able to use the still-working exception for plan sponsored by the company. And if the employee is not a 5-percent owner in that year, then even a subsequent increase in ownership will not taint the ability to rely on the still-working exception to avoid subsequent RMDs.

Example 4. Sharon is 72 years old, and is the 100% owner of Awesome Planners, Inc. Recently, Sharon decided to sell her practice to an unrelated buyer to have more time to enjoy the fruits of her labor. As part of the terms of the sale of her business, Sharon will sell 100% of her business to the buyer, but will remain a part-time employee for three years to ensure a successful transition of her client base. For the past two years, Sharon has needed to take required minimum distributions from her Awesome Planners Inc. 401(k) due to her 100% ownership of the firm. However, she is looking forward to delaying RMD after the sale, since she will be receiving both a salary and additional income due to the sale of the business, but will no longer be an owner of the business.

Unfortunately, despite the fact that Sharon will not own any of the business during her last three years of employment (the transition period after the sale), nor will any related family members, trusts, partnerships, or other entities that could be attributed back to her, Sharon will not get her wish to delay her RMDs. She will not be able to utilize the still-working exception since she was a “5-percent owner” as of the plan year end in the year she turned 70 ½. The fact that she will no longer owns any of the business in subsequent years (starting at and then beyond age 72) is irrelevant.

Strategies to Maximize the Still-Working Exception

While most people are retired by the time they turn 70 ½, some (whether by their own choice or not) may continue to work beyond that time. That trend is likely to continue, with a recent survey showing that some 37% of US workers expect to work beyond age 70. And some will continue to work well beyond that point, as there are currently more than a quarter of a million Americans age 85 or older who are still working!

Which raises the question, for those who know (or at least anticipate) that they will be working beyond age 70 ½ - what can be done to further maximize the value and opportunity of the still-working exception?

Roll Other Accounts Into the Still-Working-Exception-Eligible Plan

As noted earlier, the still-working exception applies only to the plan of the employer the person is actually still working for after 70 ½. Many people who potentially fit this bill will have other retirement accounts though, including both traditional IRAs (contributory or rollovers of prior plans), and potentially some old 401(k)s and similar plans of former employers as well.

In such situations, should a client desire, there may be the potential to delay RMDs on all retirement assets by rolling those assets into the plan of the employer for which the client still works!

Example 5. Fran is 68 years old and works for Hogan’s Heroes and Sandwiches, Inc. She is not an owner, but enjoys her work and plans to continue working for the foreseeable future. Hogan’s Heroes and Sandwiches Inc., maintains a 401(k) plan, in which Fran participates. She also has two 401(k)s from former employers, and an IRA she’s made contributions to over the years.

Assuming the Hogan’s Heroes and Sandwiches, Inc. 401(k) allows her to do so, Fran can roll in the balances from her to “old” 401(k)s, as well as her IRA. By doing so, Fran can avoid required minimum distributions on her entire retirement account balance until the year she separates from service with Hogan’s Heroes and Sandwiches, Inc.

Older employees (i.e., those approaching or at age 70 ½) interested in this strategy should make sure to consider the following:

- Accepting roll-ins of outside assets is not a mandatory requirement of qualified plans. While some plans will allow for such roll-ins, many will not. As such, it’s important to check the plan document or summary plan description to determine the viability of this strategy.

- Employer plans can generally only accept pre-tax funds from IRAs. Therefore, if an IRA contains both pre-tax and post-tax dollars, the post-tax dollars must be “left behind” in the IRA. There will still be RMDs on the post-tax dollars, but the RMD will be tax-free (assuming no gains since the roll-out of the pre-tax funds). Alternatively, the IRA owner might simply wish to distribute the entire remaining after-tax IRA balance tax-free. And rolling in the pre-tax portion to do a (tax-free) Roth conversion on the remainder is actually a popular Roth conversion strategy anyway!

- If the goal is to eliminate all Required Minimum Distributions until the employee separates from service in the future, it’s best to complete the roll-ins into the still-working-exception-eligible plan prior to the year the participant turns 70 ½. By doing so, the full, pre-tax balances of other plans and IRAs can be rolled into the still-working-exception-eligible plan and RMDs can be delayed on all pre-tax retirement savings until the year the employee separates from service.

- If this strategy is used in the year the employee turn 70 ½ or older, the still-working exception will allow an employee to delay RMDs on the funds that were in their still-working-exception-eligible plan account as of the beginning of the year. By contrast, any RMDs for IRAs or “old” employer plans must be taken for that year prior to rolling over any remaining balance into the still-working-exception-eligible plan (and RMD cannot be rolled over, and must be taken prior to any other distributions). In future years, however, RMDs will be able to be delayed on the now-larger (by virtue of the roll-ins) plan balance until the employee separates from service.

Keep Working to Make the Still Working Exception Work

As noted earlier, there is no hard and fast rule as to how many hours a person must work each year, month, or week in order to satisfy the “still working” aspect of the still-working exception. As such, some older employees, who otherwise meet the requirements of the still-working exception, and who wish to delay RMDs, may benefit from going part-time (even very part-time), instead of retiring completely.

This can be a win-win for both the older employee and the employer. Think about it… we’re talking about someone who is approaching the age of 70 ½, or is older. They may have been working in their particular field for 30, 40, or even 50 years or more. As such, they may have a wealth of knowledge that their employer can benefit from by keeping them around, even if on just a limited basis. At the same time, a typically-high-income (or else why be so concerned about continuing to defer distributions) older worker can continue to avoid RMDs.

Example 6. Jerry is 72 years old and works for Skyscraper Architects, Inc. For nearly five decades, Jerry has been honing his craft as a high-end architect, and has been an integral part of Skyscraper Architects, Inc.’s biggest projects. But Jerry has had enough of the daily grind, and wants to take a step back.

Jerry has amassed what would be a small fortune to many inside his 401(k) plan, and at the same time, he, along with his wife, has accumulated enough assets outside of his plan to never need any of the 401(k) money. In situations like this, we may be able to create a perfect win-win scenario. Instead of completely calling it quits and fully retiring from Skyscraper Architects, Inc., Jerry can try to remain on in a part-time consulting role, creating value for both Jerry and the firm.

For example, perhaps Jerry and his employer can come to an agreement where Jerry commits to coming into the office every other Friday for a half day to help mentor some of the younger architects on staff in thinking through how to solve some of the firm’s biggest problems. This could provide tremendous value to Skyscraper Architects. Inc., by helping them to retain and transition as much of Jerry’s immense intellectual capital as possible. At the same time, Jerry benefits from not only whatever payments he continues to receive, as well as maintaining some contact with his colleagues for social purposes, but also from getting to delay required minimum distributions from his Skyscraper Architects, Inc. 401(k) until such time as he fully separates from service.

If Jerry is of sound mind and body, and chooses to do so, this could easily help him delay required to distributions for an additional five or 10 years, or even longer.

Of course, while there are no hard and fast rules on how many hours a person must work in order to be considered “still working”, the IRS would certainly have the ability to attack sham employment engagements that are clearly only for the purposes of tax avoidance using such tools under the “doctrine of substance over form”. That said, the fact that the employment arrangement would generally be between an employee and an unrelated third-party does make it harder to challenge on those grounds, since presumably the unrelated third-party has no reason to create the agreement if it does not also benefit them (and not just the employee).

Divest More-Than-5-Percent Ownership Prior to the Age 70 ½ Year

Another way to potentially take advantage of the still-working exception is for a “5-percent owner” to divest of enough ownership prior to the ownership-testing date (make sure they own no more than 5%) so that they are eligible to make use of the provision as of the measuring date (December 31st of the year they turn age 70 ½).

Obviously, there are a lot of other factors to consider here. For instance:

- Does the owner/employee really want to sell their business right now? Their desire to hold ownership of a valuable (and appreciating business) may transcend any tax benefits associated with delaying RMDs.

- Does the owner want to transition the business to family members or other related parties, which won’t actually help reduce owner’s percentage ownership for purposes of the still-working exception anyway due to the family attribution rules? If so, they won’t be able to take advantage of the still working exception, regardless of when their divestiture takes place.

- How big of a planning benefit is there from delaying RMDs in the first place (as the account is still pre-tax and taxes will be due, and the still-working exception merely delays the tax bill)? If the net long-term benefit is nominal, placing an arbitrary deadline on the timing of a sale or ownership transition may be detrimental.

- Does the owner want to continue working after the transition of ownership? If the owner doesn’t plan on working after transitioning ownership, the still-working exception won’t provide any benefit in the first place!

Clearly, divesting ownership prior to 70 ½ won’t be practical, necessary, or even beneficial for all clients. Nevertheless, since a timely divestiture can allow a person to potentially continue to delay RMDs past 70 ½, it’s a strategy that must be considered. Especially if that owner is already close to the line (e.g., a 6% owner) where a relatively modest divestiture may be sufficient to get under the 5-percent owner threshold.

Create A New Business and Adopt a Qualified Plan After 70 ½

Here’s an idea that’s a little more aggressive from a tax perspective, but based on a plain reading of IRC Section 401(a)(9)(C)(ii)(I), would appear to work.

If a person creates a new business after the year in which they turn 70 ½, and then creates a 401(k) or other similar qualified plan for that business that allows roll-ins, it would appear that they would not have any required minimum distributions from that plan until they separate from service with that new employer… regardless of whether they own more than 5% of the business!

This is because the precise language of IRC Section 401(a)(9)(C)(i)(I) states “…in the case of an employee who is a 5-percent owner (as defined in section 416) with respect to the plan year ending in the calendar year in which the employee attains age 70½…” (emphasis added). As noted earlier, this wording does not call for an ownership test every year. And the Code is silent as to how a plan not in existence on the testing date should be treated. It’s reasonable to think that if Congress wanted to have such an ownership test performed more than once, they would have avoided using such narrow language in the drafting of the still-working exception provision.

With that in mind, some individuals looking to have late second careers or to work for themselves after their 70 ½ year may have a planning opportunity.

Example #7: Paula is 72 years old and is an information technology specialist with a large firm. While Paula loves her job and wants to continue working in the IT field, she wants more control over her time, and has decided to create her own S corporation, through which she will conduct IT consulting.

Suppose now that Paula establishes her consulting company, subsequently establishes a 401(k) for the company, and rolls in all of her existing pre-tax dollars from old employer plans and IRAs. It would seem that Paula can potentially take advantage of the still working exception since she was not a “5-percent owner” of her business – it didn’t even exist! – as of the plan year ending in the year she attained 70 ½. Because she only became a 5-percent owner later after having already turned age 70 ½!

Given that the IRS has never formally blessed this planning technique, it would generally be advisable to get a tax advisor’s vote of confidence prior to its use. And, of course, even if the IRS were to take the most favorable view of this strategy as possible, it would still require that the owner/employee continue performing bona fide services for the business.

Final Thoughts

Most people will have retired by the time that they turn 70 ½, but a decent percentage of workers are likely to continue working past that point. Of those workers, some will have accumulated enough savings, or will be earning enough from their continued employment, to make delaying RMDs desirable.

True, the tax man will be coming for those accounts one day, but for the time being, some savvy planning using the still-working exception can keep the “the [tax] man” at bay for a little while longer… at least for 401(k) and other qualified plan accounts (and perhaps the IRAs that can be rolled into them!).

So what do you think? How do you advise clients to maximize the still-working exception? Will this strategy become more relevant as retirees begin working longer? What other ways do you think the still-working exception can be used? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!

The Fidelity website says that “If you continue to work beyond age 72,…you may be able to defer taking distributions….until April 1 of the calendar year after the year in which you retire.” This seems to contradict the above info and seems much easier to understand and deal with.

Very thorough piece.

Does the IRS require a form to be submitted with a tax return to “apply” for or to demonstrate that a person is still working beyond age 70 1/2 and doesn’t take his RMDs? How does the IRS know or is there a requirement to tell them? if so, what form is necessary?

Jim

If a new employee is over age 70 1/2 and eventually becomes a participant in the 401(k) plan, can they defer their starting date decision after the year in which they have a balance in the plan on 12/31?

Great piece! What about the spouse of the owner of the business (S-corp) who is on payroll through the business and participates in the 401(k) plan? She owns 0% of the business, husband owns 100%. If she stays on payroll, does she qualify for the “still-working” exception?

When exactly must a > 5% owner divest of their interest in order to qualify for the still working exception to delay 401(k) RMDs. The article suggested that the “measuring date” was 12/31 of the year they turn 70.5. But Section 416 refers to a 5% owner at any time during the plan year.

For example, suppose someone is a > 5% owner turning 70 in June of 2019 and plans to work for several more years. They will be 70.5 in December of 2019. If they divest of their ownership in July of 2019, can they take advantage of the still working exception? Or would they need to have divested of their ownership before the end of 2018?

I would also like an answer to this question. I have a client who sold his business in Q1 2022 and also turned age 72 in Q1 2022. He rolled his (now terminated) 401k from his own business into the new 401k for the new employer, as he is staying on as an employee for a few years. As of 12/31/2022 he will be age 72 but NOT a >5% owner in the new business, but he was an owner of the acquired business earlier in the year. Is he subject to RMD in 2022 or does he qualify under the “still working” exception?

I nor a family member will be the “owner” of her new employer.

this reads like a very narrow (and only) exception for requried RMD’s.

Is there any case law regarding this. Its gong to affect my wife. I’m looking to set up a entity specifically to enable her to work part-time. don’t want to avoid one problem by creating another.

We have a client who has an 82 year old employee. She has been receiving annual RMDs. The question has come up that since she is still employed, does she have to receive an RMD every year? Can she pick and choose what year she wishes to receive an RMD or once she has received an RMD, must she continue each year?

I think the blog might be a bit misleading. You start out musing about how many hours you have to work to qualify for the “still working” exception. But it seems that that the answer may be zero. I work part-time as needed and will turn 72 next year, my 401K fiduciary just informed me that the will not tell me to take RMDs as long as I am listed as “active”. Looks like I don’t need to work any hours in a year to remain active.

You say that the plain reading says that you qualify for the “still working” exception if your employer considers you employed. So if you status with your employer is “employed” and not “retired” then it seems that you qualify even if you work zero hours within a tax year.

Am I wrong?

I am past the age when you have to take a RMD but have been working at my present job and have not taken any RMDs on funds in my plan. I am going to a new firm and am able to roll over my funds to my new firm’s plan. There will also be no break in my employment Will I have to take a RMD for the funds I have rolled over to the new plan.