Executive Summary

Retirement is often framed as one's "golden years", a time to enjoy the fruits of several decades of hard work. And for many retirees who have planned accordingly, this transition is not a problem as they might spend generously on travel, hobbies, or other pursuits. Nevertheless, some retirees can find it emotionally challenging to bring themselves to go beyond the basics in retirement spending (e.g., because they have a hard time switching from 'savings' mode to 'spending' mode) and can be hesitant to spend on the full range of activities that would bring them the most happiness and meaning in retirement (even though they have the resources to do so).

For instance, after a lifetime of 'maximizing' their finances (likely seeing their net worth increase steadily over time), some clients might find it difficult to see their portfolio balances decline in retirement as they draw down their assets to support their lifestyles. This could lead some to spend less than they otherwise might want to, as they prioritize maximizing their wealth (for its own sake) over enjoying their overall lifestyle. Some retired clients might feel a great deal of emotional distress when spending (and therefore could be reluctant to spend more on themselves in retirement), while still, others might be hesitant to spend due to concerns about an unpredictable future (e.g., market conditions or their own longevity).

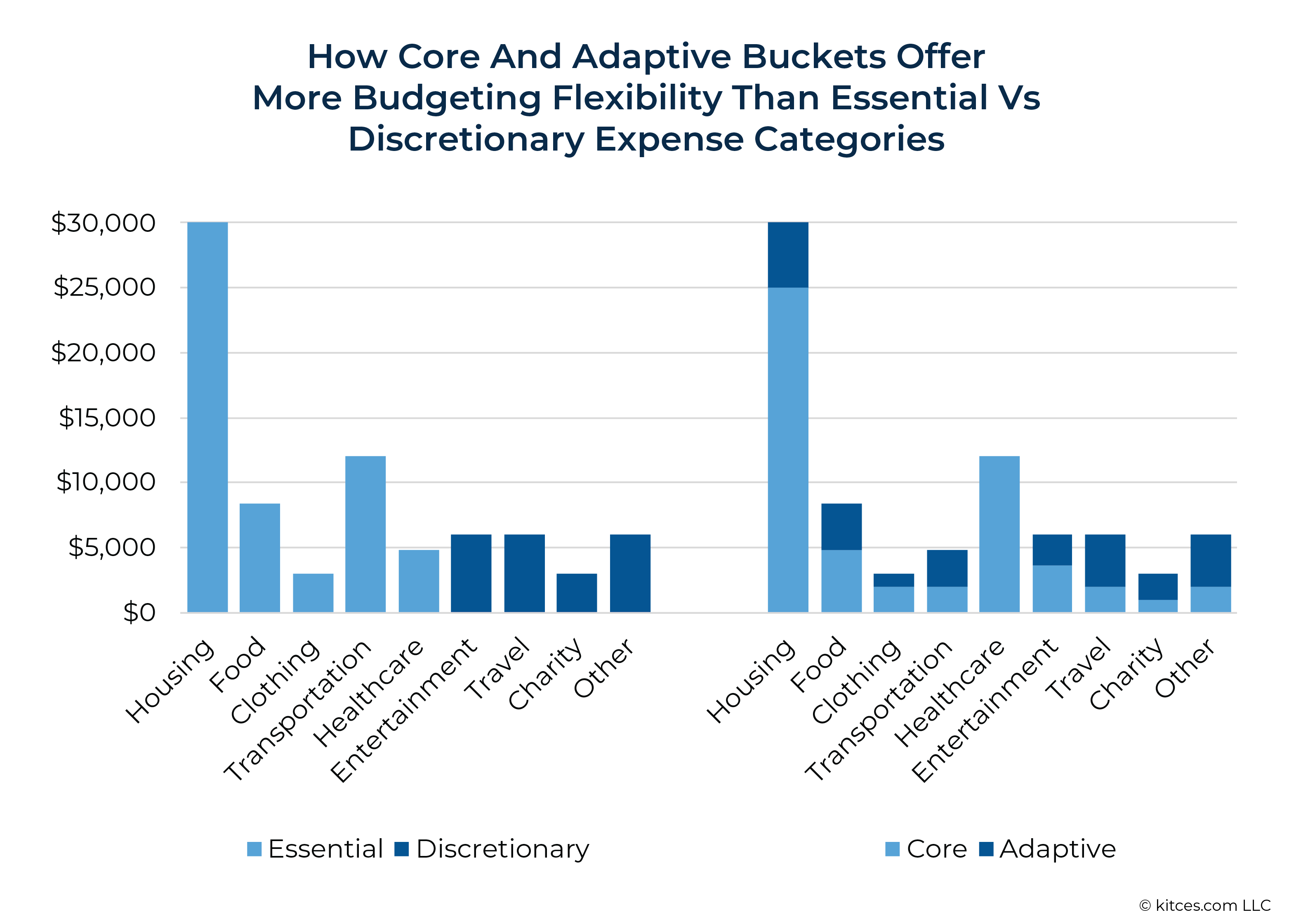

Nevertheless, advisors have an opportunity to add value through technical and behavioral-based strategies that can help hesitant clients increase their spending and have a more enjoyable retirement. For instance, framing the results of Monte Carlo analyses as a "probability of adjustment" rather than a "probability of success" can give clients more confidence that they are on a sustainable financial path. In addition, instead of grouping client expense categories as either essential (e.g., housing and food) or discretionary (e.g., entertainment, travel), advisors can group each category to have its own portion of "core" and "adaptive" expenses with 'core' buckets including spending that would otherwise be defined as "essential" spending and an amount of "discretionary" spending a client would have a hard time living without (e.g., housing – mortgage and weekly housecleaning service), leaving the "adaptive" bucket for the spending items that are truly discretionary for the client (e.g., housing – interior art). This encourages clients to 'splurge' on spending in the 'adaptive' bucket without guilt if the advisor can show that they can be confident about covering their "core" expenses. Also, given research suggesting that individuals are more likely to spend from 'guaranteed' income sources (e.g., Social Security or a defined-benefit pension), maximizing these pieces of the retirement income puzzle could give clients more confidence to spend.

On the behavioral side, clients could 'practice' retirement (e.g., through an extended sabbatical or series of mini-retirements) to experience what it would be like to spend their assets while not receiving wages. Advisors also could work with clients to explore different types of spending that have been shown to boost happiness, from 'buying' time (e.g., by hiring someone to clean their house) to spending on experiences, to philanthropic giving while they are alive (rather than waiting until their death to do so). Finally, advisors could help their clients step back and look at the 'big picture' by creating a Financial Purpose Statement or going through the Life Planning process.

Ultimately, the key point is that while some clients have no problem finding ways to spend down their nest egg in retirement (in which case an advisor can add value by ensuring they do so in a sustainable manner), the transition from saving to spending mode in retirement can be tricky for others, who might struggle to bring themselves to spend as much as they would like (even if they could afford to). For these clients, advisors can potentially add value by framing financial planning and retirement income conversations in a way that encourages these clients to explore their goals and the spending options that might fit their unique interests!

Retirement is a major transition in a client's life, both personally and financially. On the personal side, clients have to decide how to spend their time (and money) now that they are no longer working full-time. And on the financial side, retirees have to make the mental shift of moving from accumulating assets (in retirement accounts or otherwise) to decumulation, where they start to draw down their assets to support their lifestyle in retirement.

Many clients do not have a problem making the transition from accumulation to decumulation, and some might even be tempted to spend from their portfolios in an unsustainable manner. In this case, working with an advisor could be extremely valuable, as the advisor can use a variety of techniques (e.g., retirement income guardrails) to determine how much the client can sustainably spend throughout their retirement.

But for other retired clients, making the transition from saving throughout their career to spending down their assets in retirement can be a challenge, and they might pass up the opportunity to spend on experiences and other opportunities that they enjoy (even though their portfolio could support this level of spending). For these clients, advisors have an opportunity to add value through technical and behavioral-based strategies that can help hesitant clients increase their spending and have a more enjoyable retirement.

Why Some Clients Find It Difficult To Spend In Retirement

Retirement is often framed as one's 'golden years', a time to enjoy the fruits of several decades of hard work. And for many retirees, this transition is not a problem as they might spend generously on travel, hobbies, or other pursuits. Nevertheless, some retirees can find it emotionally challenging to bring themselves to spend beyond the basics in retirement (e.g., because they have a hard time switching from 'savings' mode to 'spending' mode) and can be hesitant to spend on the full range of activities that would bring them happiness and meaning in retirement (even though they have the resources to do so).

Maximizers Vs. Satisficers

According to Professor Barry Schwartz, author of "The Paradox of Choice: Why Less is More, there are two types of people in the world: "Satisficers" and "Maximizers". "Satisficers" are those who are more likely to feel content with 'good enough' and generally don't feel compelled to go for something better. "Maximizers", on the other hand, are only able to accept 'the best' or 'the most'; they can never settle for less and always push for the next level.

According to Professor Barry Schwartz, author of "The Paradox of Choice: Why Less is More, there are two types of people in the world: "Satisficers" and "Maximizers". "Satisficers" are those who are more likely to feel content with 'good enough' and generally don't feel compelled to go for something better. "Maximizers", on the other hand, are only able to accept 'the best' or 'the most'; they can never settle for less and always push for the next level.

However, after a lifetime of 'maximizing' their finances (likely seeing their net worth increase steadily over time), these clients might find it difficult to see their portfolio balances decline in retirement as they draw down their assets to support their lifestyles. This could lead some to spend less than they otherwise might want to, as they prioritize maximizing their wealth (for its own sake) over enjoying their overall lifestyle.

Tightwads Vs. Spendthrifts

Clients can also be differentiated based on how much 'pain' (typically in the form of psychological distress) they feel when spending money. In their 2008 Journal of Consumer Research paper, "Tightwads and Spendthrifts", researchers Scott Rick, Cynthia Cryder, and George Loewenstein identified 2 groups based on this idea: "Tightwads" are those who experience a significant amount of 'pain' when spending money and who end up spending less than they would ideally like to, while "Spendthrifts" experience too little 'pain' and end up spending more than they would ideally like to (notably, this can be thought of as a spectrum, as there are likely very few individuals who are purely "tightwads" or "spendthrifts").

Nerd Note:

According to a separate paper from Ricks, it is unclear whether "Tightwads" or "Spendthrifts" are more likely to work with a financial advisor. "Tightwads" have been found to be more likely to plan for their financial future, which could lead them to enlist the help of an advisor; however, the pain they experience from spending could prevent them from seeking out professional advice (even if the value of that advice might outweigh the fee they pay).

While having a client with overspending challenges might seem to be a more serious situation for an advisor (as the client might run out of assets and severely inhibit their lifestyle if they spend in an unsustainable manner), advisors could also add value by helping clients who are reluctant to spend by encouraging them to enjoy their wealth – responsibly – by spending on the things for which they really do want to use their money (if it weren't for the 'pain' of doing so).

Concern About An Unpredictable Future

While the 2 previous frameworks of "Maximizers"/" Satisficers" and "Tightwads"/" Spendthrifts" are primarily based on personality characteristics, some clients might have other reasons for keeping their spending well below sustainable levels. For instance, the rising cost of healthcare is on the minds of many clients, as potential expenses could add up over time. Others who are concerned about future market returns or the solvency of the Social Security system might also deliberately spend below their means to prepare for potential lost income from these sources. Even if advisors try to assuage some of these concerns by modeling hypothetical outcomes in financial planning software (or providing context regarding the status of the Social Security system), the potential for a worst-case scenario (e.g., market performance worse than historical returns) can be enough for some clients to still be resistant to spending if they think it threatens their ability to weather one of these hypothetical storms.

Notably, all 3 of the tendencies discussed above (maximizing wealth, feeling pain when spending, and a desire to save for future contingencies) could be identified by an advisor before the client reaches retirement (e.g., by considering their pre-retirement spending patterns or attitudes). Which means that they can take steps not only to help clients who are already retired, but also pre-retirees who are approaching the financial transition to retirement by helping them 'practice' for retirement and by creating a retirement income plan that increases their confidence to spend on the activities they prioritize.

Framing Strategies To Help Clients Spend More

When it comes to communicating the results of financial planning analyses, how outcomes are framed can influence the way a client will receive the message and decide to act. Framing is particularly important for conversations about retirement income, a topic that can potentially create significant anxiety in clients, as, without regular income from work, they might be especially concerned about whether they will be able to maintain their lifestyle throughout retirement. And for advisors with clients who are afraid (yet able) to increase their spending, framing financial planning results and how retirement income is generated in such a way that gives these clients more confidence can help them accept that spending strategies for their retirement priorities can be part of a sustainable financial plan.

Communicating Monte Carlo Results

Monte Carlo simulations are a popular method for conducting financial planning analyses for clients and are a feature of most comprehensive financial planning software programs. By distilling hundreds of pieces of information into a single number, advisors provide a data point that purports to show the percentage chance that a portfolio will not be depleted over the course of a client's life, often focusing on this probability of success as the centerpiece when presenting a financial plan. However, a Monte Carlo simulation entails major statistical and philosophical nuances, many of which might be confusing and hard to understand for clients.

For instance, the raw 'percentage chance of success' does not tell the full story of a client's potential financial future, as this result only considers a binary system of either 'failure' or 'success' (i.e., fully depleting the portfolio or not) and, when the plan 'failed', the magnitude of those hypothetical failures (i.e., when and by how much the plan 'failed') are never examined. Which means that clients might, in reality, be better (or worse) off for a given percentage chance of success.

For example, a client is likely to be more comfortable with a plan if the first year a 'failure' could occur according to the Monte Carlo simulation is at age 90 compared to a plan where failure might occur at age 80, even if both plans have the same 'percentage chance of success'. In addition, there is an important difference between performing Monte Carlo analysis for a one-time plan and on an ongoing basis with long-term clients, as ongoing clients will have the option of making spending adjustments to course correct for unanticipated conditions that impact their plan over time.

Retired clients who have ample assets to spend but are spending less than they would like because they are afraid of plan failure could be particularly sensitive to their plan's Monte Carlo results. For instance, these clients might want to curb their spending now to maximize the probability of success or to preclude the potential for dramatic reductions to their income in the future, even though the need for such major spending reductions in the future might be highly unlikely.

With this in mind, advisors can help clients develop confidence in their ability to spend in a sustainable manner by helping them better understand the dynamic nature of Monte Carlo projections and how slight spending adjustments along the way – when they are needed – can favorably impact the plan's outcome. For example, instead of communicating the 'probability of success' (which some clients might invert to 'probability of failure'), advisors can focus on the probability and magnitude of adjustment (both upward and downward) using retirement income guardrails. This approach could give clients a more realistic idea of the actual changes that would be required to keep their plan on track (and how likely they are to occur), giving them a sense of 'permission' to spend up to the amount recommended by their advisor. This could be particularly reassuring to clients concerned about worst-case scenarios, as seeing an analysis that shows exactly how much they might need to reduce their spending and when in the future they would need to do so can give them the confidence to spend more today.

Segmenting "Core" Vs. "Adaptive" Spending

A popular way to frame spending categories is to differentiate between 'essential' (e.g., housing and food) and 'discretionary' (e.g., travel and hobbies) spending. Except, in practice, 'discretionary' expenses often support an individual's psychological needs (e.g., activities that empower social and emotional well-being), so while they can survive if their 'essential' expenses are covered, they might not be able to fully thrive. Further, this framing could tempt some retirees to minimize spending on 'discretionary' items (which, by definition, are optional) in order to ensure that their 'essential' spending will be covered (even when their advisor suggests that they have sufficient assets and income sources to support not only their essential needs but also a certain amount of 'discretionary' spending).

An alternative approach to categorizing spending is to segment expenses into 'core' and 'adaptive' buckets. 'Core' spending is not only for 'essential' expenses but also for the types of spending that a retiree would have a hard time living without (e.g., a retiree might prioritize being able to stay in their current house or be able to travel to see family each year). This leaves the 'adaptive' bucket for the spending items that are truly discretionary for the client (e.g., a retiree might enjoy eating at high-end restaurants or want to buy a luxury car but would be fine without them). Notably, individual spending categories could include both 'core' and 'adaptive' spending (e.g., travel could consist of both 'core' travel to see family and 'adaptive' travel to more exotic locations).

If a financial advisor can show that a retired client could pay for their 'core' expenses with a very high probability (e.g., if these expenses can be covered with guaranteed income sources), this could free the client to 'splurge' on spending in the 'adaptive' bucket (because even in a severe market downturn, their 'core' spending would likely be untouched).

Increasing Guaranteed Income

In addition to the uncertainties of future market performance and rising costs of living, retired clients might also be reluctant to spend as much as they otherwise would like because of the inherent uncertainty of their life expectancies. If a client knew how long they were going to live and how the market would perform, they could adjust their spending precisely. However, in the absence of this information, some clients might be tempted to minimize portfolio withdrawals today, just in case, to reduce the chances of depleting their assets (whether because of excessive future withdrawals, a poor sequence of returns, or a too-short life expectancy projection.

While portfolio returns can vary over time, retirees can also access sources of 'guaranteed' income, such as Social Security benefits, defined-benefit pensions (if available to the client), or income annuities that are not dependent on market performance. In their paper Guaranteed Income: A License to Spend, researchers David Blanchett and Michael Finke explored how retiree spending changed depending on whether their income was being sourced through portfolio withdrawals or through guaranteed income sources. They estimated that investment assets generate about half of the amount of additional spending as an equal amount of wealth held in guaranteed income. Which suggests that reluctant spenders might be more confident in increasing their spending if a larger portion of their income were generated from guaranteed sources (which can also help protect them from longevity risk and sequence of return risk) compared to seeing their portfolio balance decline every time they withdrawal funds (even if it is being done in a sustainable manner).

One way to generate additional guaranteed income in retirement could be for the client to delay taking Social Security benefits, thereby increasing their monthly benefit for the remainder of their life. This could be an appealing strategy for 'maximizers' (who naturally might seek to maximize the size of their Social Security benefit) as well as those retirees concerned about longevity or other future contingencies (as the increased benefit sets a higher 'floor' for their income). Another option is for the client to convert a portion of their portfolio into guaranteed income by purchasing an income annuity that will provide a stream of income for the remainder of their life. While doing so requires the upfront 'pain' of buying the annuity, the guaranteed income stream could reduce the mental burden of spending in the future as the client receives regular income payments. Those with access to a defined benefit pension also have a source of guaranteed income and, based on Blanchett and Finke's research, by electing to take their pension at retirement (instead of receiving a lump-sum payout), could be encouraged to spend more of their pension dollars.

In sum, a variety of options are available for advisors to frame financial planning analyses as well as retirement income and spending in a way that can encourage reluctant clients to make the most of their wealth in retirement (in a sustainable manner).

Behavioral Tactics To Boost Retirement Spending

In addition to spending and income strategies that can alleviate client anxiety over using their wealth during retirement, there is a range of behavioral-based tactics that can also help clients overcome mental hurdles that hold them back from spending more. As while a client's transition to retirement involves changes not only to the way they generate income but also to the type of expenses the retiree will have. Which means clients often need to make significant adjustments to their relationship with money in retirement.

For instance, the client's income source will no longer be dependent on a regular salary, but will now be based on portfolio income and Social Security benefits. And they might have reduced costs for work-related transportation and clothing, but increased expenses for travel and leisure. Amid this backdrop, advisors can help (potentially reluctant) clients both in advance of retirement and in retirement to adjust to this new dynamic and spend in a (sustainable) way that will support a more fulfilling retirement.

'Practicing' Retirement To Reduce The Pain Of Spending

Given the dramatic transition often associated with retirement, advisors could help clients experience what retirement will be like in advance by encouraging them to 'practice' before they actually retire. For instance, advisors could support working clients in taking an extended sabbatical or a series of 'mini-retirements' to get a glimpse of what retirement life might be like and how their spending would change. For example, by encouraging clients to pay for a large expense during their working years to see how it feels, advisors can help them acclimate to the 'pain' of making a big purchase (e.g., paying for a large trip) while working before they do it again in retirement, which could lessen the psychological challenge of doing it again in the future. This can be important, especially for individuals who may feel more psychological distress than others when spending and, as a result, avoid spending on things they might otherwise enjoy.

Another way to mitigate anxiety associated with spending more during retirement is to explore different approaches to spending that may feel more acceptable to retirees (or even to those 'practicing' retirement). Scott Rick's review of the dynamics of "Tightwad" and "Spendthrift" spending suggests that those who feel significant pain when spending tend to spend more on 'luxury' purchases when using a credit card rather than cash (possibly because using a credit card allows an individual to delay actually paying for the good from cash or their bank account). Which means that reluctant spenders might also feel better spending if they use credit cards that earn rewards that can pay for their travel.

Exploring Different Types Of Spending

Some retired clients might conceptually understand that they can afford to spend more money but, even though they like the idea of using their wealth on things they will enjoy, they may have a hard time generating ideas for how to spend their money after a long career spent saving for retirement and focusing much of their time on working. An advisor could add value in this situation by offering ideas that the client might not have considered.

For instance, in the book "Happy Money: The Science of Happier Spending", authors Elizabeth Dunn and Michael Norton highlight the potential benefits of spending money to 'buy' time. As an example, a retired client could pay someone else to clean their house and mow their lawn instead of doing it themselves, saving them time that could be used for more enjoyable pursuits (though some clients might find housecleaning and gardening tasks fulfilling!).

For instance, in the book "Happy Money: The Science of Happier Spending", authors Elizabeth Dunn and Michael Norton highlight the potential benefits of spending money to 'buy' time. As an example, a retired client could pay someone else to clean their house and mow their lawn instead of doing it themselves, saving them time that could be used for more enjoyable pursuits (though some clients might find housecleaning and gardening tasks fulfilling!).

Some clients who were thrifty throughout their careers might be hesitant to spend money on 'things' like a bigger house or a luxury car. For these clients, spending money on 'experiences' (e.g., travel or arts events) might be more satisfying instead. In addition, an advisor might encourage these clients to consider material goods that can be used for experiences; a recent research study found that these purchases that are both 'material' and 'experiential' (e.g., a vacation house or a swimming pool) can generate similar happiness to many 'purely experiential' items (e.g., seeing a concert).

In addition to buying time and experiences, another way clients could boost spending is through giving to others. While clients frequently want to leave a bequest to family members or charities upon their deaths (when they know they will no longer need the money), many clients could make significant gifts during their lifetimes without threatening the success of their financial plans. Such giving not only offers the client the satisfaction of seeing recipients enjoy their gifts, but also provides for a more immediate gift to recipients, many of whom could benefit from receiving such resources sooner rather than later (e.g., funding the down payment for a child's home now, when they are getting started in their career, could be more valuable to them than receiving an inheritance many years later, when they are older and have accumulated significant assets of their own).

Further, those with charitable intent might additionally be incentivized by the tax benefits of giving to charities (e.g., by making Qualified Charitable Distributions [QCDs] from their IRA to minimize the tax bite of Required Minimum Distribution [RMD] obligations). This could be particularly appealing to certain "Maximizer" clients who want to minimize their tax bill as much as possible.

Looking At The Big Picture

More broadly, advisors could help clients explore their priorities in retirement, which could help them unlock spending opportunities they hadn't considered previously. For instance, George Kinder's 3 Life Planning Questions can allow an advisor to probe deeper into a client's hopes, dreams, and fears in order to develop more relevant and impactful financial plans. For clients who are having trouble getting themselves to spend, working through Kinder's 1st question, which asks clients to dream about their future and freedom if money were not an issue, could be a particularly useful exercise.

Another option could be to encourage clients to create a Financial Purpose Statement, which essentially consists of a simple statement that crystallizes the purpose of money in the client's life. Doing so can help them make mindful spending decisions that are more aligned with their goals and values.

Ultimately, the key point is that while some clients have no problem finding ways to spend down their nest egg in retirement (in which case an advisor can add value by ensuring they do so in a sustainable manner), the transition from 'saving' to 'spending' mode in retirement can be tricky for others, who might not be able to bring themselves to spend as much as they would like (even if they could afford to). For these clients, advisors can potentially add value by framing financial planning and retirement income conversations in a way that encourages these clients to spend and by helping these clients explore their goals and the spending options that might fit their unique interests!

Leave a Reply