Executive Summary

After years of anxiety over the scheduled sunset of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) at the end of 2025, the widely anticipated legislation extending and replacing TCJA – also known as the "One Big Beautiful Bill Act" (OBBBA) – was signed into law on July 4, 2025.

At its core, OBBBA makes permanent many of the provisions of the original TCJA, including TCJA's tax brackets, increased standard deduction, Section 199A deduction for Qualified Business Income (QBI), and increased Child Tax Credit. All of these receive minor tweaks but remain substantially the same as they were under TCJA. However, the $10,000 limitation on State And Local Tax (SALT) deductions is temporarily increased to $40,000 under the new law. Higher-income households may see this deduction phased back down to the $10,000 limit, and all households will again be subject to the $10,000 SALT cap beginning in 2030.

Additionally, OBBBA introduces several new below-the-line tax deductions while amending numerous others. The new law introduces a temporary $6,000 deduction for seniors age 65+, deductions of up to $25,000 of income from tips and overtime wages, and up to $10,000 of interest paid on qualifying auto loans. All of these provisions take effect from 2025 through 2028. Among several changes to itemized deductions, the new law most notably introduces a 0.5%-of-AGI 'floor' on charitable contributions, reducing the deductible value of amounts donated to charity. It also imposes a new limitation for taxpayers in the 37% tax bracket, capping the 'value' of itemized deductions to 35% of taxable income.

Also included are a host of other tax changes, including (but not limited to) reduced phaseout thresholds and a faster phaseout rate for the Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT) exemption, an expansion of eligible 529 plan expenses to cover K–12 materials and postsecondary credentials, and an extension of the Qualified Opportunity Zone program. The law also increases the gift and estate tax exclusion to $15 million per person and creates a new "Trump account", a type of IRA that can be funded at a young age (and without any earned income).

Ultimately, while many of the individual provisions under OBBBA are relatively minor changes from existing law, together they represent a substantial shift in tax policy – one that adds a significant amount of complexity to tax planning with the number of new deductions, phaseout rules, and effective dates governing OBBBA's provisions. Which will make it all the more valuable for advisors to understand how their clients stand to be impacted by the new rules, so they engage in proactive planning that takes all the new (and old) rules into account and translates them into actionable strategies for their clients!

Final text of the One Big Beautiful Bill Act as enacted

On July 4, 2025, after a nearly two-month legislative sprint following the release of the House Ways and Means Committee's first draft of their long-awaited tax legislation, the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA) was signed into law. The final version of the law ultimately reflects the Senate's version of the legislation, which differs from the House version in some significant ways despite keeping many of its core provisions.

The new law effectively serves as an extension (or replacement) of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017, which was set to largely expire at the end of 2025. As such, OBBBA's enactment finally puts to rest nearly eight years of speculation over what the Internal Revenue Code – and the tax pictures of millions of Americans – will look like at the start of 2026.

The new law makes permanent many of the provisions that TCJA had introduced only temporarily (due to the Republican-controlled Senate's use of a controversial budgeting maneuver designed to lower the nominal 'cost' of the law, allowing the permanent changes to fit within the reconciliation framework that Republicans needed to pass the law with a simple majority in the Senate). The permanent extensions include TCJA's tax brackets, increased standard deduction, Section 199A deduction for Qualified Business Income (QBI), and the increased gift and estate tax exemption threshold.

Additionally, OBBBA introduces numerous tweaks to rules already in effect, new deductions for auto loan interest and income from tips and overtime wages, and a new type of IRA-like savings account to help children begin saving for retirement at a young age.

Notably, beyond OBBBA's extensions, modifications, and additions to tax rules, the new law also contains numerous other provisions, including some that could have significant consequences on Medicaid and student loan planning in the years ahead. However, the following sections cover 'just' the tax provisions for individuals, families, and small business owners (with other topics perhaps being covered in future articles to come!).

Tax Brackets Under OBBBA

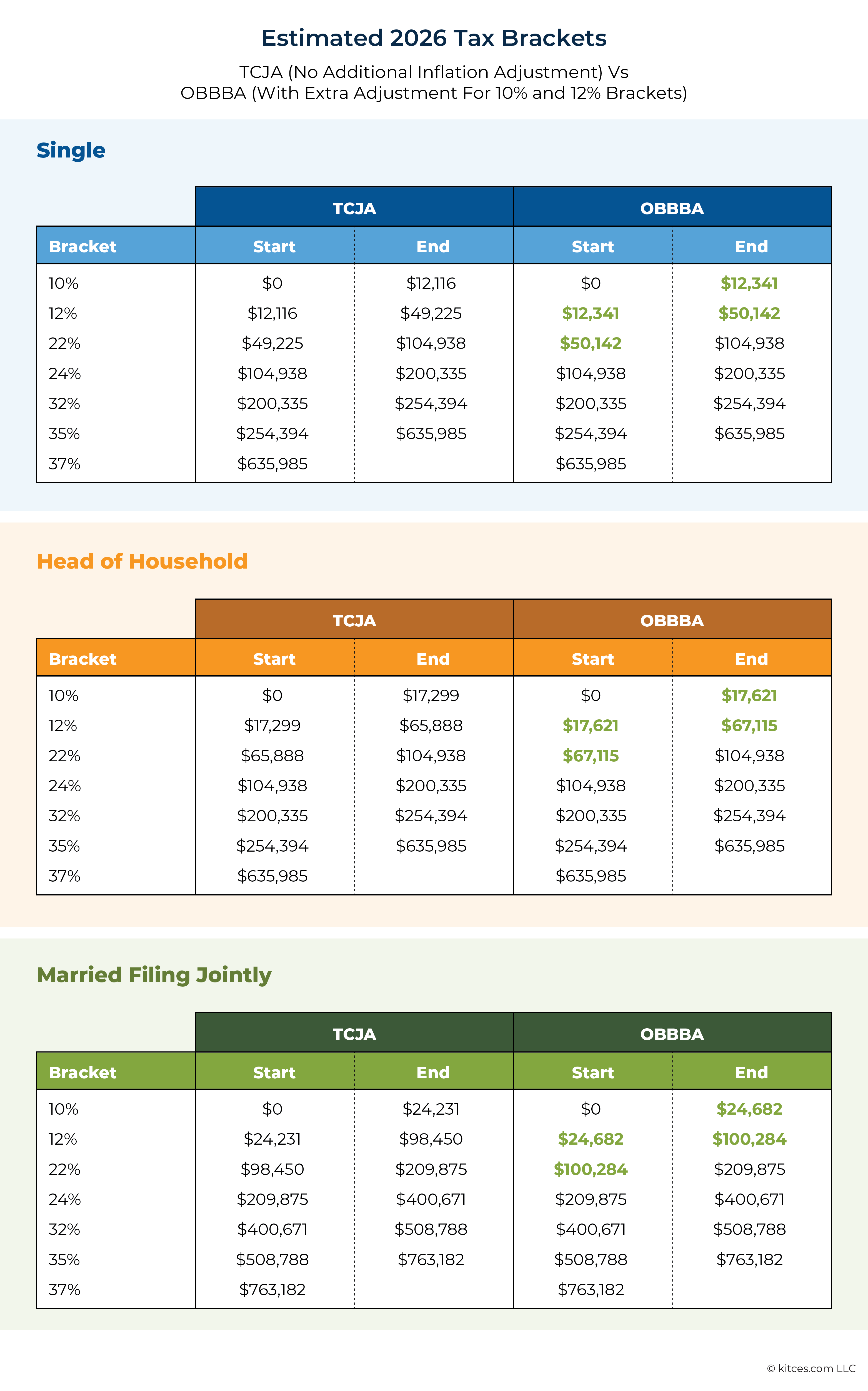

Section 70101 of the new law permanently extends the tax brackets of 10%, 12%, 22%, 24%, 32%, 35%, and 37% that have been in place since TCJA became effective in 2018.

The one minor change, which will begin in 2026, is to set the 'base' year for inflation adjustments back one year to 2016 – but only for the 10% and 12% tax brackets. Effectively, this means that the 10% and 12% brackets will receive an extra inflation adjustment bump in 2026, slightly increasing their income thresholds compared to what they would have been without the adjustment.

As shown below, these changes will amount to, depending on filing status, a few hundred extra dollars in the 10% bracket and one to two thousand extra dollars in the 12% bracket.

The end result of these adjustments will be to slightly reduce effective tax rates for most households by having more income taxed in the lowest two brackets. However, the change may not be large enough to make a noticeable difference in the total taxes paid.

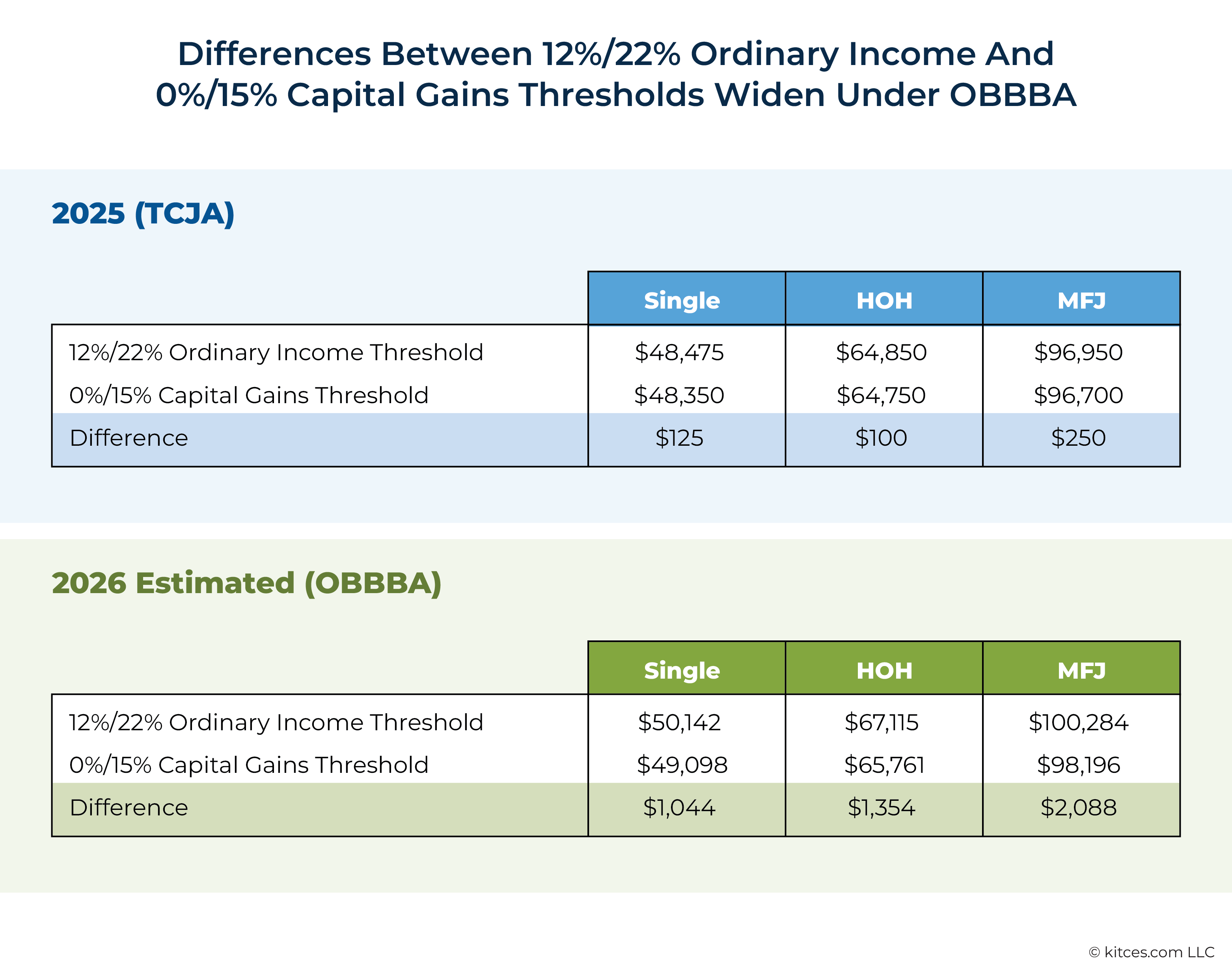

Another (possibly unintended) consequence is that the breakpoint between the 12% and 22% ordinary income tax brackets is now further away from the breakpoint between the 0% and 15% capital gains brackets. As shown below, while the current ordinary income thresholds are only $125–$250 higher than the respective capital gains thresholds, under OBBBA's new tax brackets, those numbers will be closer to $1,000–$2,000 apart.

It isn't a major change, but it will require some extra attention for individuals recognizing capital gains, particularly when harvesting capital gains in the 0% capital gains tax bracket. Under TCJA, the difference between the ordinary income and capital gains thresholds was small enough that it was generally safe to assume that someone in the 12% ordinary income bracket would also be in the 0% capital gains bracket. Now, there's a bit more space between those thresholds, creating a rare scenario where it would be possible to incur more tax by recognizing capital gains (at 15%) than ordinary income (at 12%)!

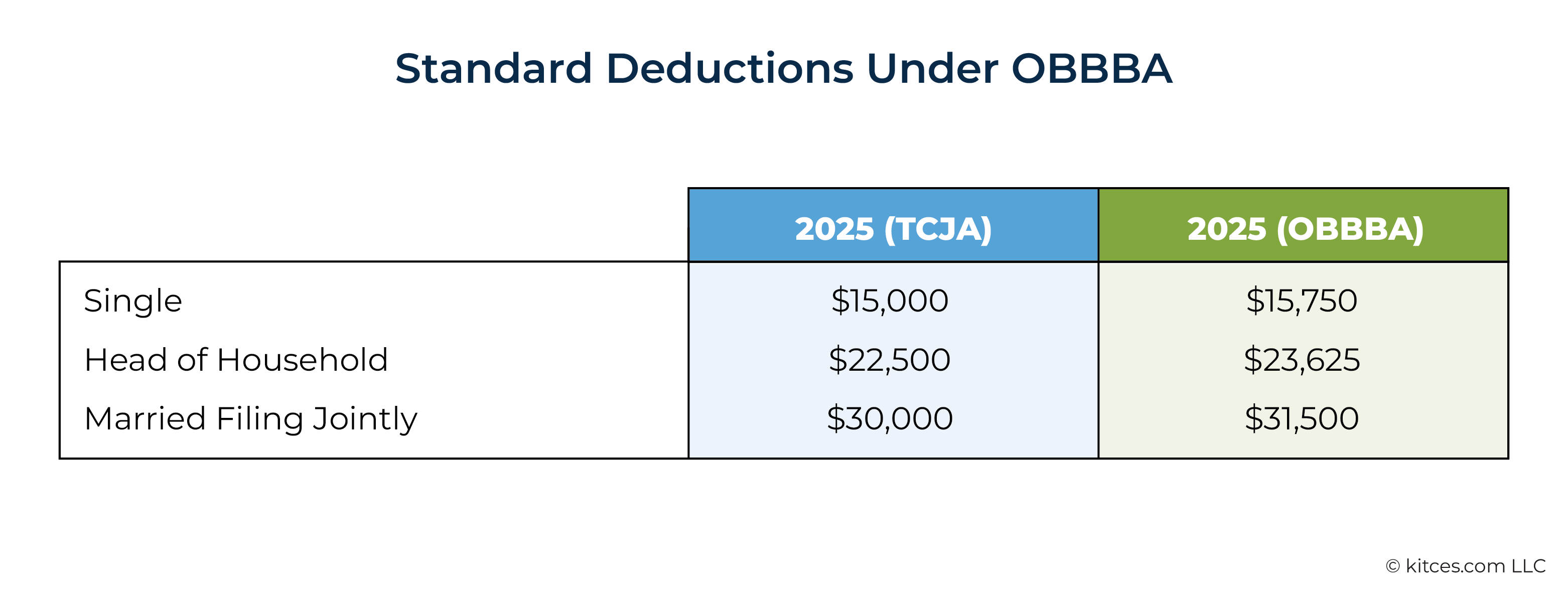

Standard Deduction Permanently Increased, With Temporary Additional Deductions For Seniors Age 65+

Under Section 70102 of the OBBBA, the standard deduction will receive a slight increase starting this year in 2025. The original 2025 levels under TCJA will rise from $15,000 to $15,750 for single filers; $22,500 to $23,625 for heads of household; and $30,000 to $31,500 for joint filers. These amounts, adjusted for inflation, will be permanent going forward.

Section 70103 of the new law also creates a temporary additional deduction for seniors age 65 or older from 2025 through 2028. The new deduction is set at $6,000, or $12,000 for joint filers where both spouses are age 65+. The deduction phases out, however, at a rate of 6% of the amount of the household's Modified Adjusted Gross Income (MAGI) over $75,000 (single) or $150,000 (joint). In effect, households with over $175,000 (single), $250,000 (joint) will be fully phased out of the additional senior deduction. Notably, for married couples who are both age 65+, both spouses' deductions are reduced simultaneously by the phaseout: For example, a couple with $200,000 of MAGI would have each of their deductions reduced by 6% × ($200,000 − $150,000) = $3,000, resulting in a total deduction of 2 × ($6,000 − $3,000) = $6,000.

Nerd Note:

In most of the new law's provisions, MAGI is defined as "the adjusted gross income of the taxpayer for the taxable year increased by any amount excluded from gross income under section 911, 931, or 933". Those IRC sections relate to income excluded under the Foreign Earned Income Exclusion and the exclusions for income earned while residing in U.S. territories or possessions like Puerto Rico, Guam, American Samoa, and the Northern Mariana Islands, which only factor in for a small minority of U.S. taxpayers.

For the vast majority of households, then, when MAGI is referenced relating to one of the OBBBA's provisions, it's simply interchangeable with Adjusted Gross Income (AGI).

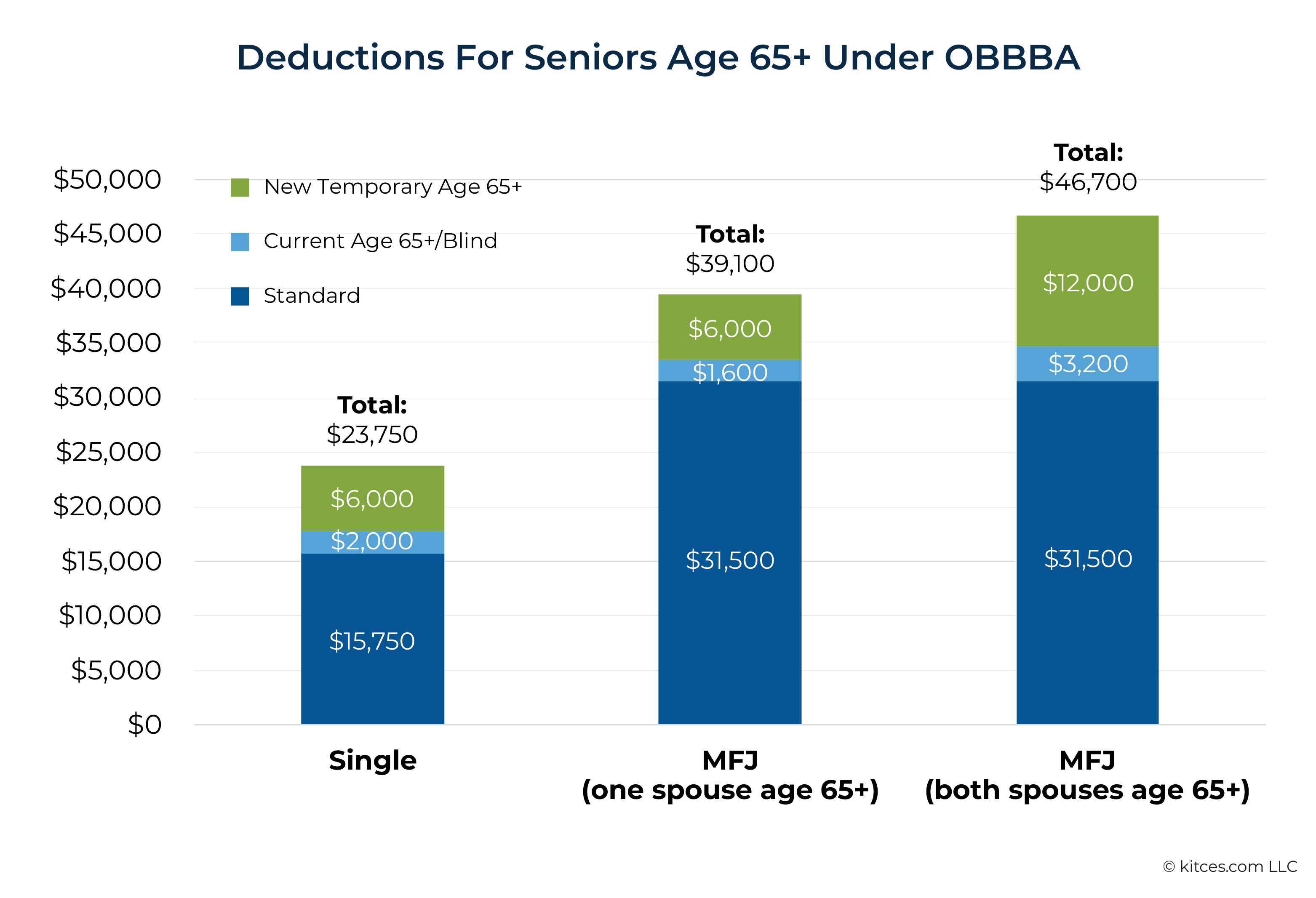

Notably, the temporary age 65+ deduction is on top of the additional standard deduction given to individuals who are either age 65+ or blind, which adds an extra $2,000 to the standard deduction for single filers or $1,600 for each eligible married filer. Which means that, as shown below, between the 'normal' standard deduction, the current age 65+ or blind deduction, and the new temporary age 65+ deduction, households with members age 65+ are eligible for up to $23,750 in deductions for single filers, $39,100 for joint filers with one spouse age 65+, and $46,700 for joint filers where both spouses are age 65+.

The age 65+ deduction, though available regardless of whether a household uses the standard deduction or itemizes their deductions, is a 'below-the-line' deduction that is taken after calculating Adjusted Gross Income (AGI). Which means that, while the deduction does reduce taxable income (and therefore the amount of tax owed), it doesn't have an impact on any tax provisions based on AGI, such as the taxability of Social Security benefits (discussed more in the section below), the deduction floor for medical expenses and charitable contributions (discussed further down), or the phaseout of the deduction for auto loan interest (also discussed below).

Social Security Income Still Subject To Tax

Notwithstanding the temporary additional age 65+ deduction, what the OBBBA does not do is exempt Social Security income from taxation. This was the source of some confusion in the wake of an email sent by the Social Security Administration shortly after OBBBA's enactment that claimed the new law would result in nearly 90% of Social Security beneficiaries owing no tax on their benefits.

That claim appears to be based on an analysis from the White House Council of Economic Advisors estimating that, under the new law, 88% of Social Security beneficiaries will have total deductions (including the standard deduction, current age 65+/blind deduction, and new temporary age 65+ deduction) that exceed their taxable Social Security benefits. However, the assumption in that analysis is that all of those deductions offset Social Security income first, rather than any of the taxpayer's other taxable income. In reality, the deductions are agnostic about the income they're offsetting – they would be available regardless of whether the individual was receiving Social Security benefits or not.

In practice, while the new temporary age 65+ deduction will offset some income for those who are eligible for it, the deduction doesn't directly tie to Social Security benefits in any way. A 65-year-old who hasn't filed for Social Security benefits yet will be eligible for the exact same deduction as one who has already begun receiving them.

This matters from a tax planning perspective because the way Social Security benefits are actually taxed depends greatly on what other income the taxpayer has. If a taxpayer's "provisional income" (essentially their AGI, plus any tax-exempt interest, plus 50% of their Social Security benefits) exceeds certain limits, their Social Security benefits are taxed at higher rates: 0% if below $25,000 (single) or $32,000 (joint), 50% if between those amounts and $34,000 (single) or $44,000 (joint), and 85% if above those amounts. In other words, the higher the taxpayer's AGI, the higher the percentage of their Social Security income that gets taxed, which can lead to extremely high marginal tax rates of 40% or more on income received in the zone of increasing taxation of Social Security benefits.

If an individual believes their Social Security benefits are no longer taxable, or that their age 65+ deductions directly reduce their taxable Social Security income, they might choose to recognize additional income (e.g., by converting pre-tax dollars to Roth). In reality, that additional income could increase the portion of their Social Security benefits subject to tax. So it's worth remembering – and emphasizing to clients – that the standard rules for the taxation of Social Security benefits still apply, and using the additional age 65+ deduction as an opportunity to recognize other income may result in that income being taxed at a much higher marginal rate if it causes more of their Social Security benefits to become taxable.

Changes To Itemized Deductions

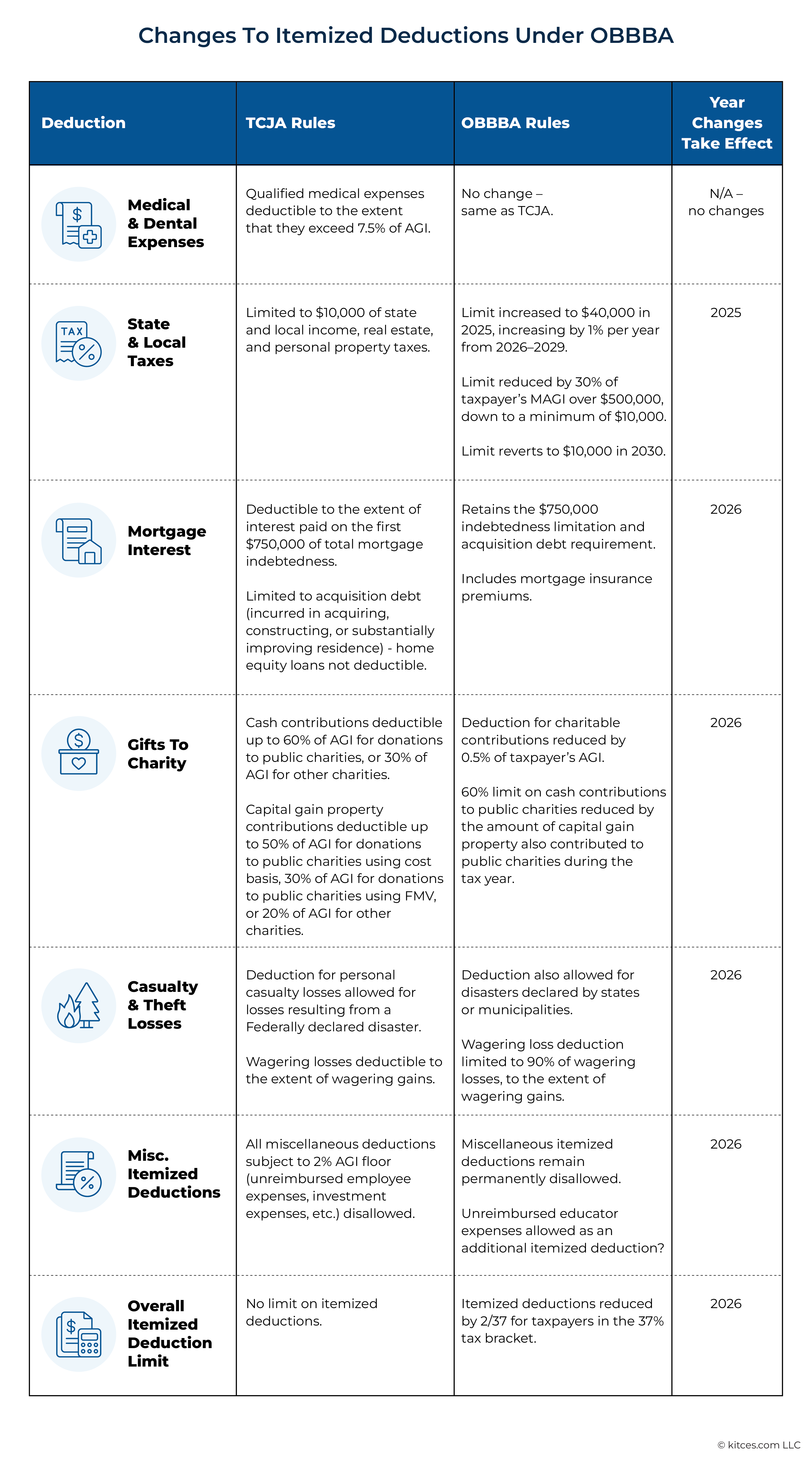

The final version of OBBBA makes a number of changes to itemized deductions, with varying degrees of impact. In fact, the only itemized deduction that appears to be completely untouched under OBBBA is the deduction for qualified medical and dental expenses exceeding 7.5% of AGI. Otherwise, every other category of itemized deduction listed on Schedule A has been changed in some way.

State And Local Tax (SALT) Deduction Temporarily Increased To $40,000

One of the biggest questions heading into the negotiations for this law was where the limitation on State And Local Taxes (SALT), which was fixed at $10,000 under TCJA, would end up in the final law. Numerous proposals were discussed, including increasing the deduction for married filers and indexing it to inflation, and Republicans from higher tax states like New York and New Jersey threatened to vote against the legislation if the $10,000 limit wasn't increased.

In the end, those holdouts got some, but not all, of what they wished for.

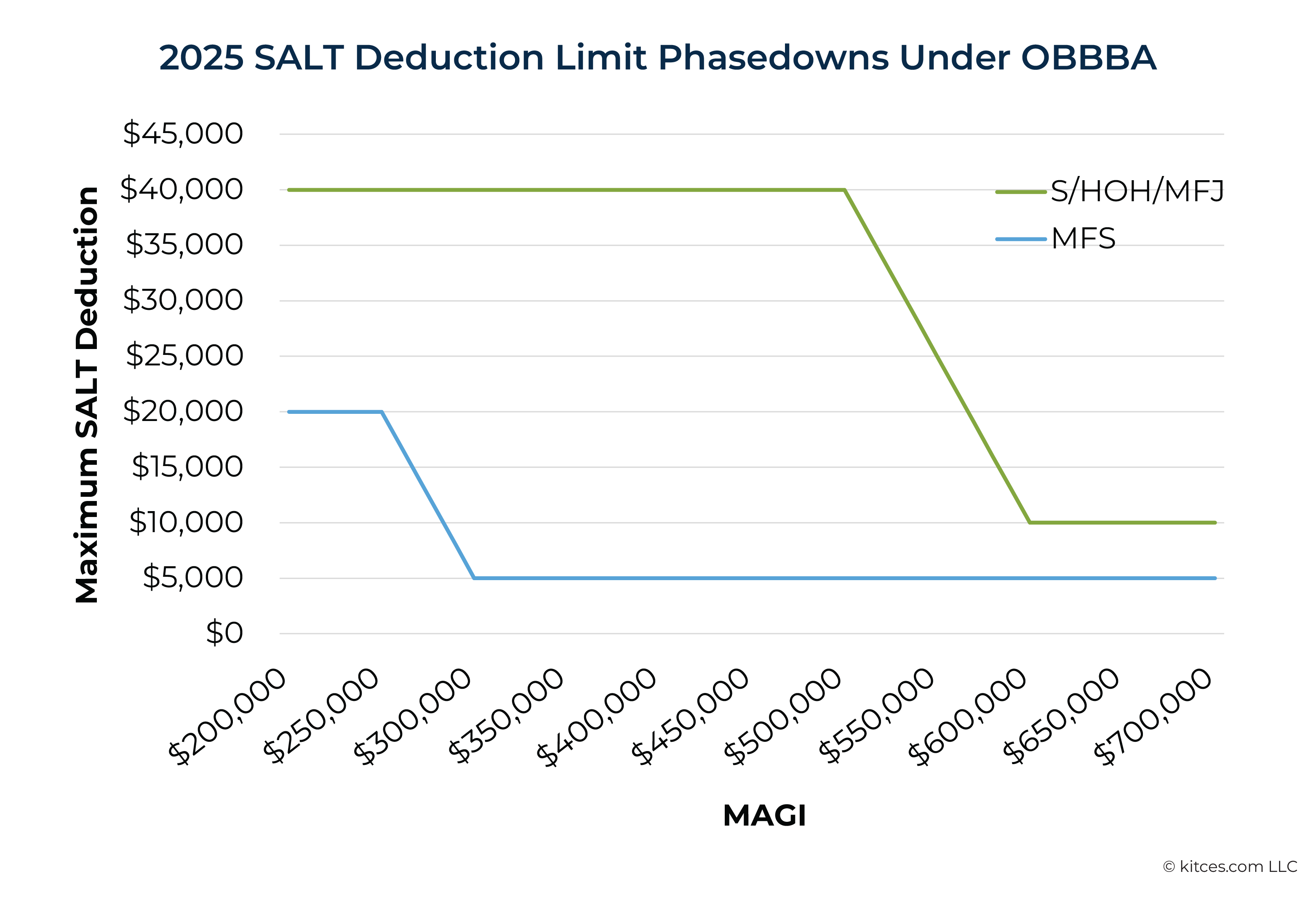

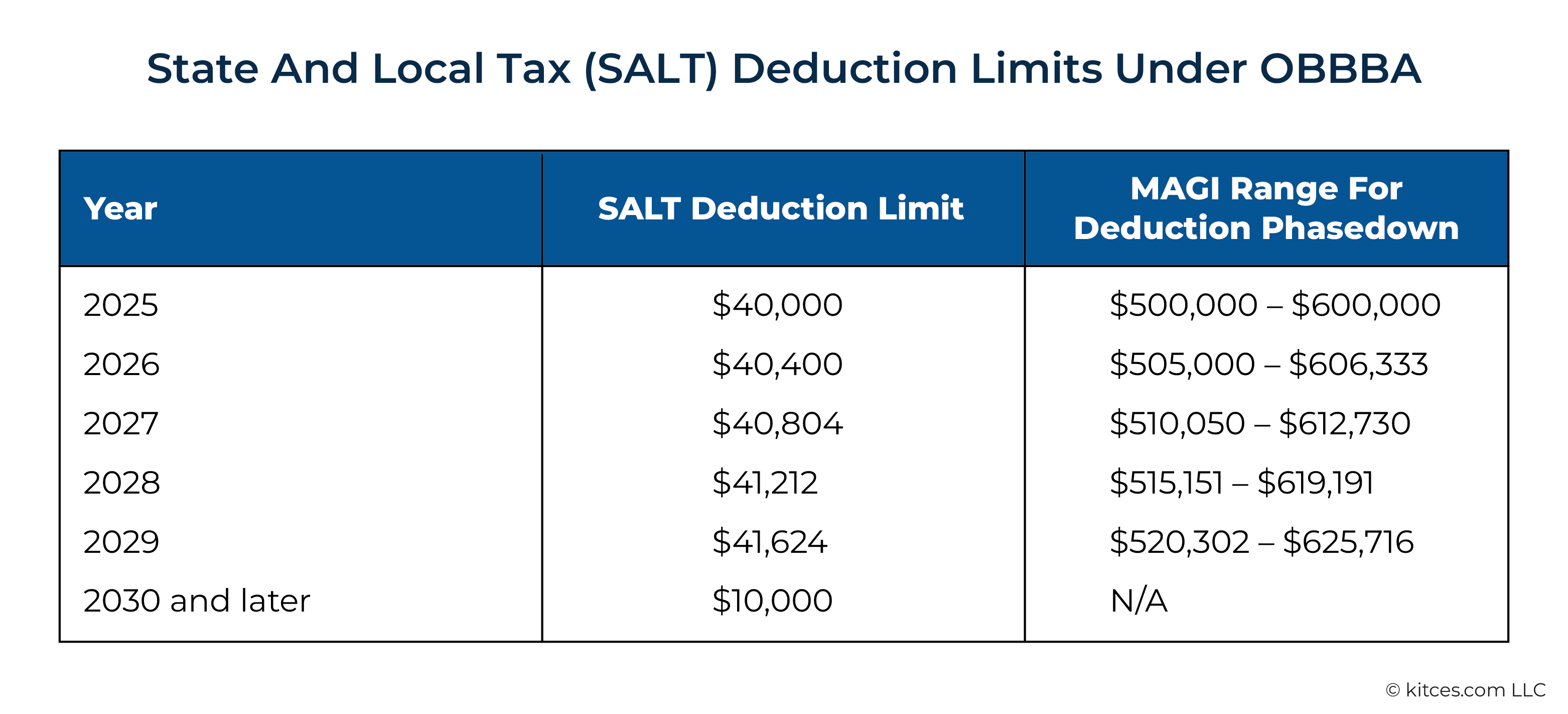

Under Section 70120 of OBBBA, the SALT deduction limit will be increased to $40,000 starting in 2025. From 2026 to 2029, that limit will increase by a fixed 1% each year, with the cap reverting to $10,000 in 2030. The higher limit is the same for all filing statuses except married filing separately, whose limit is 50% of the other limits (for example, then, the married filing separately limit in 2025 will be $20,000).

Not all households will be eligible for the higher SALT deduction limit under OBBBA, however. The new law includes a phasedown provision reducing the deduction limit by 30% of the amount by which the taxpayer's MAGI exceeds $500,000 (with the phasedown threshold, like the maximum deduction, also increasing by 1% per year through 2029).

The SALT deduction limit is phased down to a minimum of $10,000 after MAGI reaches the upper limit of the phasedown range ($600,000 in 2025). Like the deduction limit, the phasedown thresholds for married filing separately are 50% of those for other filing statuses.

As the graphic above shows, the new phasedown thresholds create a steep drop-off in the amount of SALT deduction allowed as the taxpayer's income moves through the phasedown range. Which means that taxpayers within that range – to the extent that they have state and local taxes to deduct – could have significant marginal tax rates on any income recognized or deferred.

Example 1: Janna is a single filer with $500,000 of MAGI. Her deductions include $40,000 of state and local taxes, $20,000 of mortgage interest, and $10,000 of deductible charitable contributions.

Because Janna's AGI is at the bottom of the new SALT deduction phasedown range, every dollar of income that she receives simultaneously reduces her SALT deduction by 30%. In other words, each dollar she earns adds $1.30 to her taxable income.

Because her taxable income puts her in the 35% tax bracket, then, her effective marginal rate on income earned within the phaseout range is 1.3 × 35% = 45.5%.

As the example above shows, taxpayers with MAGI between $500,000 and $600,000 who also pay significant amounts in state and local taxes – and have enough other itemized deductions to exceed the standard deduction even if their SALT deduction is phased down – can face higher effective marginal tax rates within this phaseout range.

They may be best served by planning carefully to avoid incurring additional income while in this phaseout range, since each new dollar earned would effectively be taxed at a higher rate than their nominal Federal tax bracket. Conversely, they could find ways to take additional 'above-the-line' deductions – those that reduce AGI – because doing so lowers taxable income and magnifies the increase in the allowable SALT deduction. Or they might consider bunching deductions together into a single year to reduce their income under the phaseout threshold, in order to take the standard deduction in other years where their income would phase them out of the higher SALT deduction.

As noted above, the SALT deduction limit is scheduled to revert to $10,000 starting in 2030, meaning that, in all likelihood, there will be another congressional battle over the future of the SALT deduction in the coming years. Until then, however, the fixed 1% increases in both the overall limit and the phasedown threshold allow us to know what to plan for in the coming years (assuming a future Congress doesn't step in and change things again before then).

One thing of note for owners of pass-through businesses (e.g., partnerships and S corporations) is that the final version of OBBBA does not include any restrictions on state-level Pass-Through Entity Taxes (PTETs), which allow the owners of such businesses to effectively circumvent the SALT deduction cap by structuring their state tax payments as a business expense (which is still fully deductible) rather than a personal expense (which is subject to the SALT deduction cap). The original House of Representatives version of OBBBA included new rules to effectively eliminate the benefits of PTETs, but they were left out of the Senate version of the bill. Although the higher deduction cap makes it less likely that even many affluent business owners will need to rely on PTETs to fully deduct their state tax payments, higher-earning partners and owners will still have that as an option going forward.

Mortgage Insurance Premiums Includable In Deductible Mortgage Interest

Under TCJA, taxpayers can deduct their interest payments on their first $750,000 of mortgage indebtedness. The deduction is restricted to interest paid on "acquisition indebtedness" – that is, loans that were used to buy, build, or improve the taxpayer's residence (and not home equity loans or lines of credit used to draw cash from home equity for other purposes).

Additionally, since 2022, it has not been possible to deduct mortgage insurance premiums, which are generally paid by homeowners who owe more than 80% of their home's value in mortgage debt and can add a few hundred dollars to homeowners' monthly mortgage payments.

Section 70108 of OBBBA retains the $750,000 indebtedness limit and acquisition indebtedness requirements from TCJA. However, it also restores the deductibility of mortgage insurance premiums permanently starting in 2026 (which is significant since the deduction had previously been kept in place by a series of short-term extensions, which allowed it to lapse in 2022 when Congress declined to renew it).

So while the new law won't change the mortgage interest deduction for most taxpayers (including those who took mortgages before December 15, 2017, who are grandfathered into the pre-TCJA indebtedness limit of $1 million), it will provide a bigger deduction for some homeowners with FHA or VA loans, or others who paid a less-than-20% down payment on their home.

Charitable Contributions Subject To A New 0.5%-of-AGI Floor

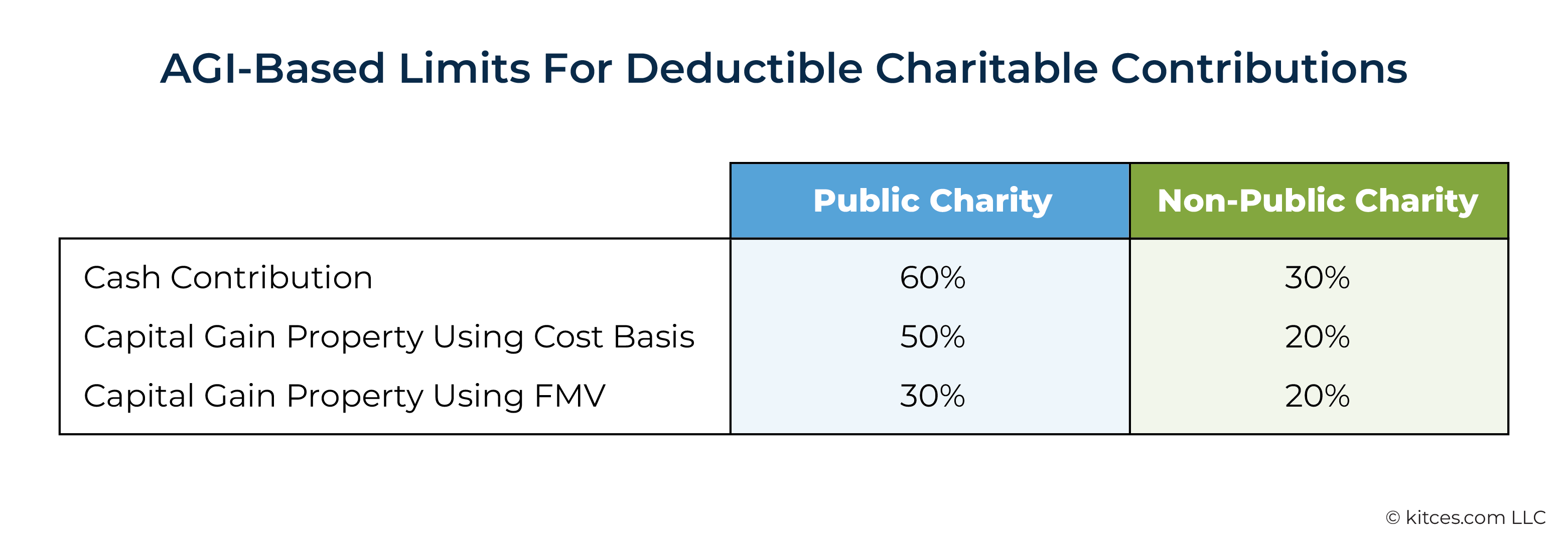

Charitable contributions have long been subject to AGI-based limitations on their deductibility, depending on the type of property donated and the type of organization donated to. For public charities, cash contributions are deductible up to 60% of AGI, and noncash contributions are deductible up to 50% (when using cost basis to figure the deduction) or 30% (when using fair market value).

Deductible contributions to other types of organizations are limited to 30% (for cash contributions) or 20% (for all noncash contributions) of AGI. If a contribution exceeds these limits, the excess contribution is not deductible in that year, but can be carried forward to be deducted in a future year for up to five years.

For the first time, Section 70425 of OBBBA also sets a floor on the deductibility of charitable contributions equal to 0.5% of AGI, starting in 2026. This means that deductions are only allowed to the extent an individual's otherwise-deductible contributions exceed 0.5% of their AGI, with the floor being applied before the upper AGI percentage limits described above.

For the first time, Section 70425 of OBBBA also sets a floor on the deductibility of charitable contributions equal to 0.5% of AGI, starting in 2026. This means that deductions are only allowed to the extent an individual's otherwise-deductible contributions exceed 0.5% of their AGI, with the floor being applied before the upper AGI percentage limits described above.

The new law sets an ordering rule specifying which types of charitable contributions are reduced first by the 0.5%-of-AGI floor, as follows:

- Capital gain property contributed to non-public charities;

- Capital gain property contributed to public charities using fair market value;

- Cash contributions to non-public charities;

- Qualified conservation contributions (a specific type of contribution of land or real estate for conservation purposes);

- Capital gain property contributed to public charities using cost basis; and

- Cash contributions to public charities.

If a charitable contribution exceeds the upper AGI limits for that contribution type and part of the deduction is carried over to the following year, then any of the 0.5%-of-AGI floor attributable to that contribution type is also carried over.

Example 2: Sheila is a single taxpayer with $200,000 of AGI. After receiving a substantial inheritance, she decides to make several large charitable contributions. Sheila contributes $50,000 in cash to various public charities and an additional $50,000 in appreciated securities to a private foundation (which is considered a non-public charity for the purposes of the ordering rules).

Sheila's $200,000 AGI means that her deductible contributions will be subject to a floor of $200,000 × 0.5% = $1,000. Per the ordering rules above, that $1,000 reduction will first be subtracted from the appreciated securities contributed to the private foundation before figuring the upper deduction limits for both types of contribution.

For the appreciated securities contributed to the private foundation, then, the net deductible amount of $49,000 (i.e., after the $1,000 floor is subtracted from the $50,000 total contribution) is subject to the 20% AGI limit. Meaning that only $200,000 × 20% = $40,000 is allowable as a deductible contribution this year, with the remaining $9,000 being carried over to next year.

The cash contributions to public charities are subject to an aggregate limit of 60% of AGI, or $200,000 × 60% = $120,000, meaning that all $50,000 of those contributions is deductible.

Sheila's total charitable deduction for the year is $40,000 (appreciated stock contribution to private foundation) + $50,000 (cash contribution to public charity) = $90,000.

The $9,000 of appreciated securities contributed to the private foundation that exceeded the 20% AGI limit is carried over to next year.

Additionally, because the contribution of appreciated securities was reduced by $1,000 by the 0.5% AGI floor, that $1,000 is added to the amount that can be carried over, adding up to $10,000 in carryover contributions for next year.

The new floor on deductibility of charitable organizations means that, for high-income taxpayers who plan to make charitable contributions, it may be best to do so in 2025 before the 0.5%-of-AGI floor takes effect in 2026. Notably, the 0.5% reduction is carried forward to the following year only if the contribution exceeds the AGI limit and is deferred to a future year. As a result, it can sometimes make sense to contribute more than the annual AGI limit, since doing so allows the 0.5%-of-AGI reduction to be "used" later instead of otherwise being simply lost.

Changes To Limitations On Casualty And Wagering Loss Deductions

The Internal Revenue Code allows for deductions for a limited variety of personal losses, including losses from wagering and from "personal casualty losses" stemming from disasters like fires, floods, and earthquakes.

Under TCJA, individuals who partake in wagering transactions (i.e., gambling) have been allowed to deduct their wagering losses, but only to the extent of their wagering gains. In other words, if a gambler has more losses than gains in a year, they can only deduct losses up to the amount of gains, resulting in $0 net income from wagering for the year.

Under Section 70114 of OBBA, however, only 90% of wagering losses will be deductible starting in 2026, while the overall deductible wagering loss remains limited to the amount of wagering gains. So for instance, if a gambler has $100,000 in wagering losses and $100,000 in wagering gains in a year, they'll only be able to deduct $100,000 × 90% = $90,000 in losses, resulting in $10,000 of net taxable income from wagering despite having $0 in actual net income from wagering.

Under TCJA, taxpayers could only deduct personal casualty losses if the loss resulted from a Federally declared disaster. Section 70109 OBBBA slightly loosens this rule by also allowing deductions for losses from state-declared disasters beginning in 2026. In either case, the casualty loss deduction remains limited to losses not compensated by insurance and only to the extent the losses exceed 10% of the taxpayer's AGI.

Miscellaneous Itemized Deductions Permanently Eliminated, But Educator Expenses To Be Added As A New Itemized Deduction?

Prior to TCJA, taxpayers could deduct a slew of "miscellaneous" itemized deductions on Schedule A, including investment expenses (e.g., financial advisory fees paid from taxable investment accounts) and unreimbursed employee expenses. These deductions were allowed in aggregate to the extent they exceeded 2% of the taxpayer's AGI. TCJA suspended the miscellaneous expense deduction, and Section 70110 of OBBBA makes that suspension permanent (despite lobbying by CFP Board and other financial industry groups to restore at least the investment fee deduction and expand it to other types of non-investment-related financial planning fees).

However, OBBBA makes one change that could be significant for teachers, coaches, and other educators who spend personal funds on educational materials for their students. The text of the bill adds "educator expenses" to the list of itemized deductions in IRC Section 67 that are not considered miscellaneous deductions. Which effectively means that educator expenses would become their own (non-miscellaneous) itemized deduction starting when the provision takes effect in 2026.

Currently, there is a deduction for educator expenses allowed on Schedule 1 (available to taxpayers who don't itemize deductions), but it's limited to $300 (or $600 for married spouses who are both educators) and excludes some expenses for health or physical education teachers. Under the Schedule A version of the deduction, these limitation would be lifted, allowing educators to potentially deduct more of their out-of-pocket costs for educational materials and supplies. However, they would need to itemize deductions to claim this benefit, which may still exclude many educators from being able to use it.

Itemized Deduction Limitations For The 37% Tax Bracket

Up until 2017, higher-income taxpayers who itemized deductions were subject to the Pease limitation, which reduced the total allowable amount of a taxpayer's itemized deductions by 3% of the amount by which their AGI exceeded a threshold: $261,500 for single filers, $287,650 for head of household filers, and $313,800 for joint filers in 2017. The effect was roughly equivalent to a 1% surtax on income for itemizers above those thresholds.

However, TCJA temporarily suspended the Pease limitation, removing any income-based limitation on the amount of itemized deductions any taxpayer could claim.

Section 70111 of OBBBA permanently repeals the Pease limitation, but also replaces it with a different limitation on itemized deductions starting in 2026. This new rule applies only to higher-income taxpayers in the top 37% Federal tax bracket (those with taxable income above $626,350 for single and head of household filers, or $751,600 for joint filers).

The new limitation reduces allowable itemized deductions by 2/37 of the lesser of:

- The taxpayer's total itemized deductions; or

- The amount by which their taxable income plus total itemized deductions exceeds the 37% bracket threshold (before applying the limitation).

Why 2/37? The goal of the limitation is to reduce the tax value of itemized deductions for those in the top tax bracket who, by the math of how deductions from taxable income translate into hard-dollar tax savings, stand to benefit more from their deductions than those in lower brackets. For example, under current law, a taxpayer in the 37% bracket receives a 37-cent reduction in tax for every $1 of deductions claimed. By reducing allowable deductions by 2/37, the effective tax benefit of those deductions would drop from 37% to 35% – a way to preserve some of the deduction's value while narrowing the benefit for the highest earners.

Example 3: Anna and Bennett are a married couple with $1 million in AGI and $200,000 of itemized deductions, resulting in $800,000 of taxable income. This puts them in the 37% marginal tax bracket.

Under current law, Anna and Bennett can fully deduct their itemized deductions, saving $200,000 × 37% = $74,000 in tax.

Under the new law, however, their itemized deductions would be reduced by 2/37 of the lesser of:

- Their total itemized deductions ($200,000); or

- The amount by which their taxable income ($800,000) plus itemized deductions ($200,000) exceeds the 37% bracket threshold ($751,600), or ($800,000 + $200,000) − $751,600 = $248,400.

Because $200,000 is the lesser amount, their allowable deductions are reduced by 2/37 × $200,000 = $10,811. Which means their total allowable itemized deductions would equal $200,000 – $10,811 = $189,189.

The tax savings from these deductions under the new law would be $189,189 × 37% = $70,000, equivalent to 35% of their total itemized deductions.

Notably, OBBBA specifies that the new itemized deduction limitation will be ignored for purposes of calculating the Section 199A deduction for Qualified Business Income (QBI). This matters because taxable income is used both in the calculation of QBI (which phases down above certain levels of taxable income) and the calculation of the deduction itself (which is limited to 20% of the household's taxable income).

As shown below, while most of the changes to itemized deductions under OBBBA are relatively minor – with the exception of notable provisions like the increased SALT deduction cap and the new 0.5%-of-AGI floor on charitable contributions – they are broad enough in scope to cover nearly all deduction categories on Schedule A. Also notable is the fact that the SALT deduction cap is the only change taking effect in 2025, with the remainder scheduled to begin in 2026.

Section 199A Deduction Extended, With Only Minor Adjustments

TCJA created a major new tax deduction for pass-through business owners (i.e., sole proprietorships, partnerships, and S corporations) with the Section 199A deduction for Qualified Business Income (QBI). In short, Section 199A allows eligible business owners to deduct up to 20% of the lesser of their QBI from qualifying pass-through businesses or their total taxable income (minus net capital gains).

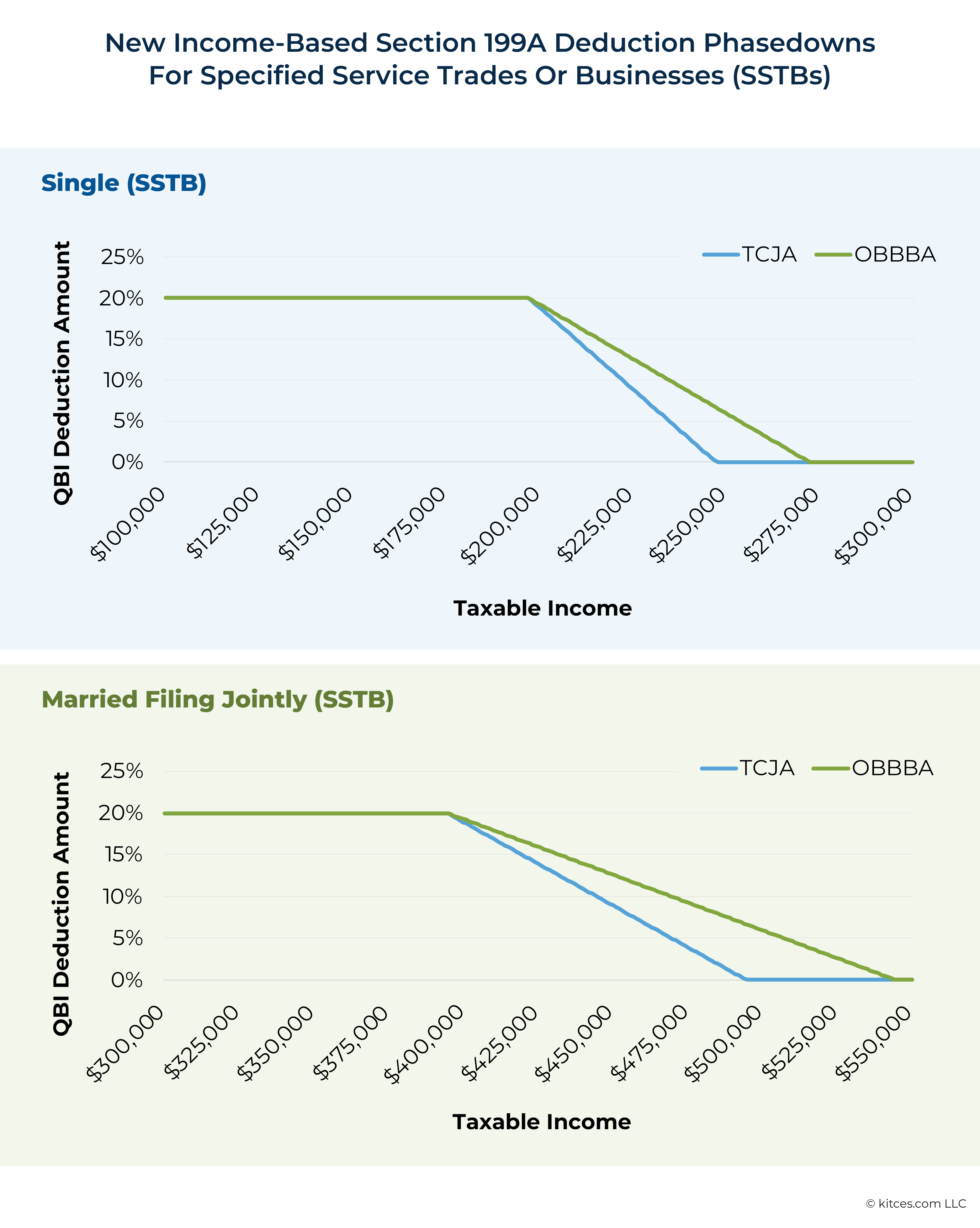

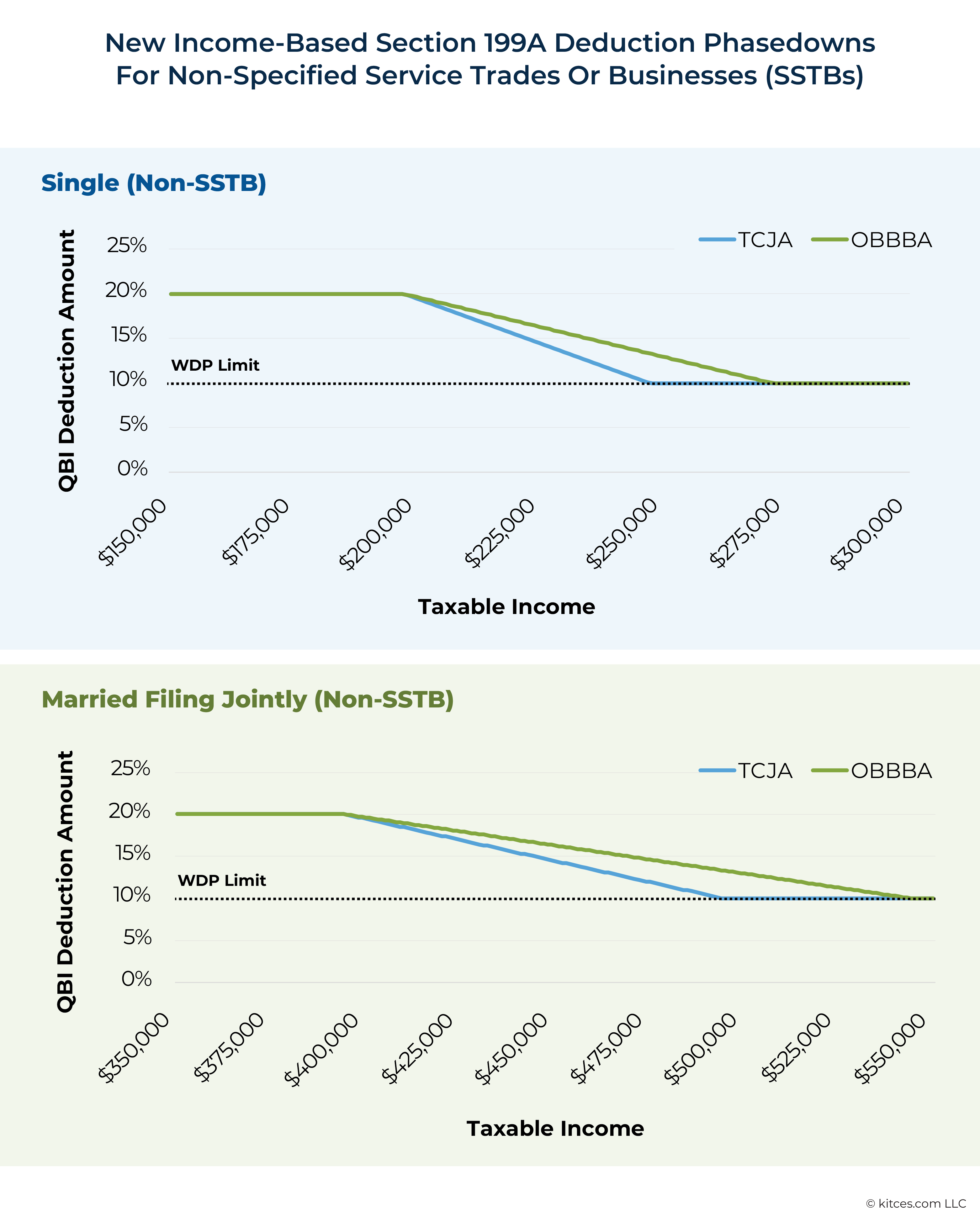

The original House of Representatives version of OBBBA included some significant changes to the Section 199A deduction, including an increase in the deduction amount from 20% to 23% of QBI and a new method of phasing out the deduction for higher-income households, which could have significantly benefited owners of high-income Specified Service Trade or Businesses (SSTBs).

However, the final version of OBBBA stripped out most of those changes, resulting in a continuation of the deduction largely as it has existed since it took effect in 2018. Section 70105 of OBBBA includes two notable, though relatively minor, changes compared to the original bill.

Increased Phaseout Ranges For Higher-Income Business Owners

First, the law amends the Section 199A deduction's phaseout rules so that the deduction will be completely phased out at slightly higher income levels than under the current rule.

Under current law, business owners with taxable income over the applicable threshold – $197,300 for single filers and $394,600 for joint – are subject to a phaseout range of $50,000 (single) or $100,000 (joint).

For owners of a Specified Service Trade or Business (SSTB) – such as doctors, lawyers, consultants, accountants, financial advisors, athletes, or artists – the deduction phases out entirely over their applicable income range. The reduction is calculated as the ratio of the amount by which taxable income exceeds the threshold to the full phaseout range.

For instance, a married SSTB owner with $80,000 of income above the threshold would lose $80,000 ÷ $100,000 (the total phaseout range for married filers) = 80% of their deduction. Once taxable income exceeds the threshold by $100,000 or more, the deduction is fully eliminated.

For non-SSTB owners, the deduction also phases out over the same income ranges ($50,000 for single filers and $100,000 for joint), but not to $0. Instead, it phases down to the Wage and Depreciable Property (WDP) limit, defined as the greater of:

- 50% of the business's W-2 wages; or

- 25% of W-2 wages plus 2.5% of the unadjusted basis of depreciable property owned by the business.

For example, a married non-SSTB owner with $80,000 of income above the threshold would lose $80,000 ÷ $100,000 = 80% of the difference between their full 20% QBI deduction and the applicable WDP limit.

The final version of OBBBA keeps the general structure of these phaseout rules, as well as the applicable thresholds of taxable income above which the deduction begins to phase out. However, the new law increases the phaseout range from $50,000 (single) and $100,000 (joint) to $75,000 and $150,000, respectively, beginning in 2026. As a result, the deduction will be completely phased down – either to $0 for SSTB owners or to the WDP limit for non-SSTB owners – at $272,300 of taxable income for single filers and $544,600 for joint filers.

Minimum Deduction For Active Qualified Business Income

The final law also creates a new minimum deduction of $400 for taxpayers with at least $1,000 of "active qualified business income" starting in 2026. Since the Section 199A deduction is generally equal to 20% of QBI, a taxpayer would normally need $2,000 of QBI to result in a $400 deduction. This change essentially guarantees a baseline level of deduction for taxpayers with some amount of active business activity.

In defining "active qualified business income", the law adopts the IRC Section 469(h) definition of "material participation". This standard is typically used to distinguish between active and passive business activity. It requires regular, continuous, and substantial involvement in business operations, and generally excludes interests in passive investment vehicles like limited partnerships.

Both the $400 minimum deduction and the $1,000 active QBI requirement will be indexed to inflation, beginning in 2027.

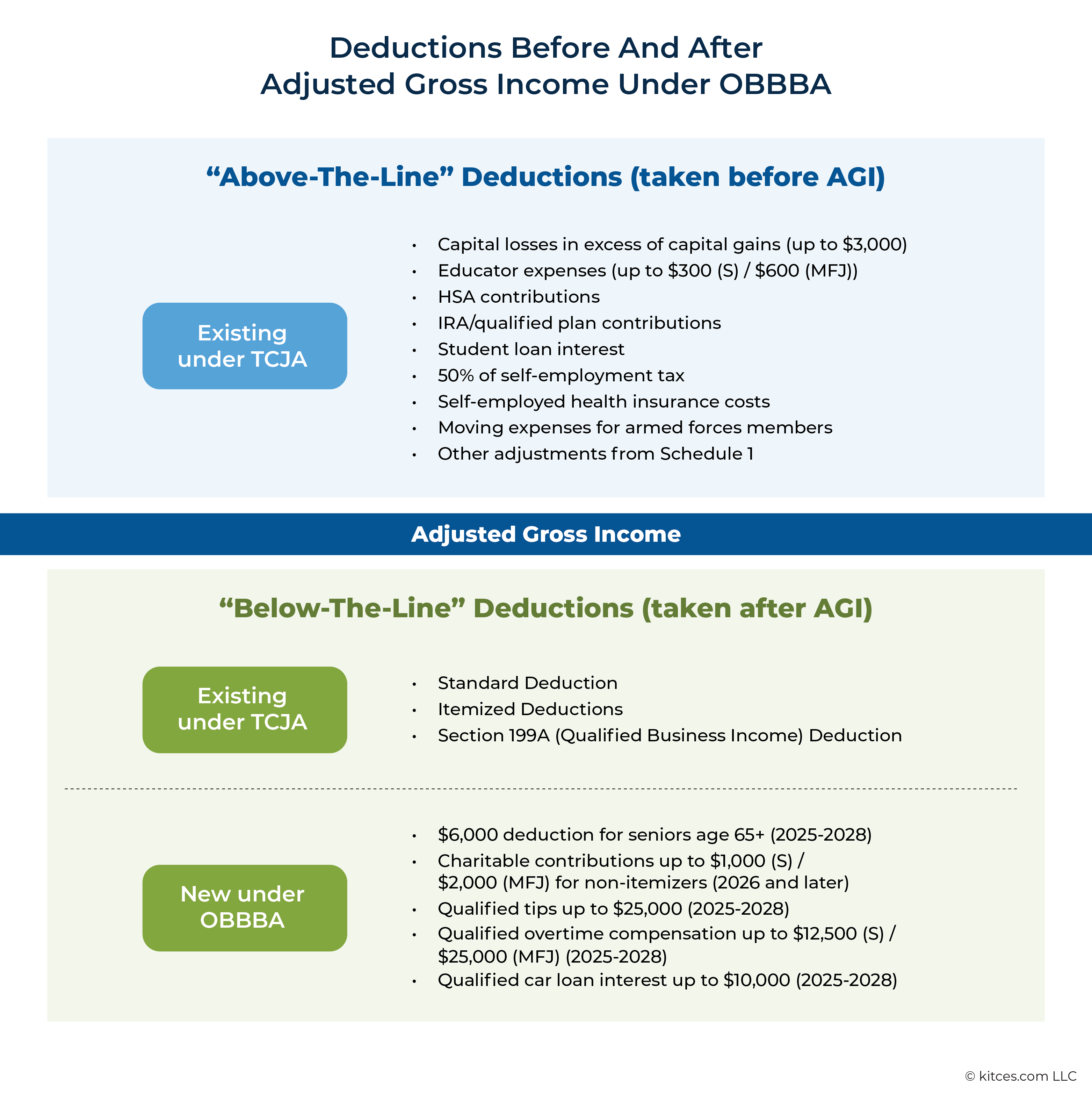

New Below-The-Line Deductions

Tax deductions can broadly be thought of as either 'above-the-line' or 'below-the-line', with the 'line' referring to Adjusted Gross Income (AGI). Above-the-line deductions are deducted from income before AGI, which means that they reduce a taxpayer's AGI and are therefore can be helpful for many phaseouts and other calculations that are based on AGI (e.g., the taxation of Social Security benefits, the new 0.5% floor on charitable contributions, or the phaseout of the Child Tax Credit).

Below-the-line deductions, on the other hand, are subtracted from income after AGI is calculated. As a result, they don't reduce AGI itself. While they do reduce taxable income and therefore still provide some tax benefit, they don't help with phaseouts or thresholds that are based on AGI rather than taxable income – unlike above-the-line deductions, which can affect those calculations.

While all above-the-line deductions are available to any taxpayers who are eligible for them, most below-the-line deductions are consolidated into the group of itemized deductions listed on Schedule A. These only provide a tax benefit if the taxpayer's itemized deductions exceed the standard deduction. The notable exception to this since 2018 has been the Section 199A deduction for Qualified Business Income (QBI): Even though this is a below-the-line deduction, it's available whether a taxpayer itemizes deductions or takes the standard deduction.

OBBBA introduces several new below-the-line deductions that, like Section 199A, are available to both itemizers and non-itemizers. One of these is the new temporary $6,000 deduction for seniors age 65+, discussed earlier. In addition, OBBBA creates four more below-the-line deductions:

- A deduction for charitable contributions for taxpayers who take the standard deduction;

- A deduction for workers who earn income through tips;

- A deduction for workers who earn overtime wages; and

- A deduction for qualified auto loan interest.

Charitable Contribution Deduction For Non-Itemizers

Generally speaking, in order to receive a deduction for amounts contributed to charitable organizations, a taxpayer needs to itemize their deductions. As the standard deduction has steadily increased over the years – and was nearly doubled by the enactment of TCJA in 2018 – it has become increasingly rare for households to itemize deductions unless they pay significant amounts of mortgage interest and/or state and local taxes, which are more common among higher-income households.

As a result, for many lower- and middle-income households, there hasn't been much incentive from a tax perspective to make charitable donations in recent years. The CARES Act of 2020, passed during the COVID-19 pandemic, temporarily created a new charitable deduction of up to $300 for single filers and $600 for joint filers who claimed the standard deduction – but that provision only lasted two years and expired after 2021.

Section 70424 of OBBBA permanently restores the charitable deduction for non-itemizers starting in 2026 and increases the maximum deduction to $1,000 for single filers and $2,000 for joint filers. Unlike the Schedule A version of the charitable deduction, this deduction is not subject to the 0.5% floor on the deductibility of charitable contributions. Which means that taxpayers can take the new deduction regardless of income or other deductions.

Notably, as with the original CARES Act version of the non-itemizer charitable deduction, qualifying charitable contributions must be in cash (i.e., no other types of property like household goods or securities). Additionally, contributions cannot be made to Section 509(a)(3) "supporting organizations" or used to establish or maintain a donor-advised fund.

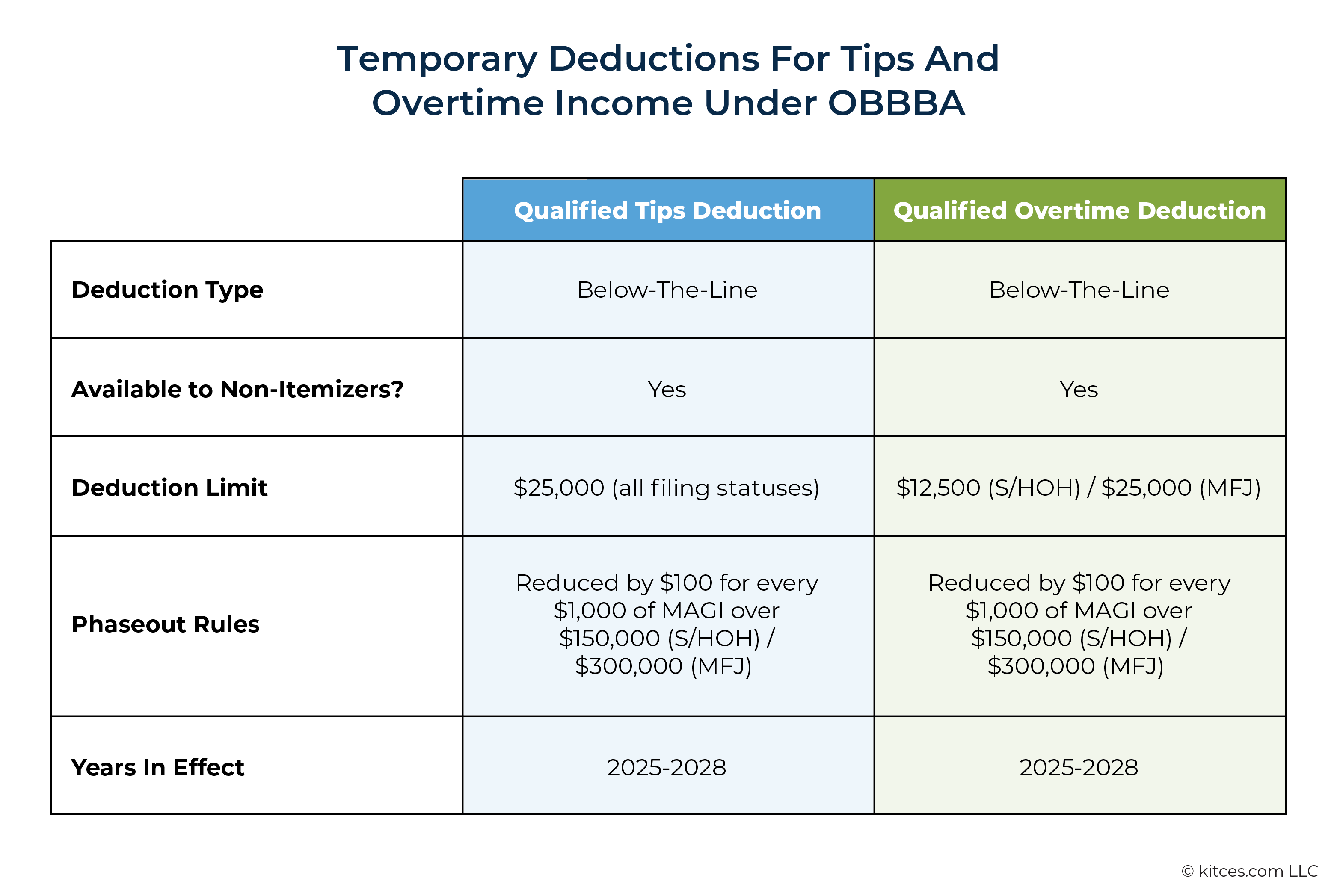

Qualified Tips Deduction

As one of three tax proposals heavily promoted by Donald Trump on the campaign trail in 2024 (the other two being the elimination of taxes on overtime wages and auto loan interest, both of which are discussed below), some version of "No Tax on Tips" was almost certain to make it into the final tax law.

The "No Tax on Tips" provision in Section 70201 of OBBBA doesn't actually eliminate taxes on tips – income from tips is still subject to payroll tax, included in Adjusted Gross Income (AGI), and may also be subject to state income tax. But it does create a deduction under a newly created IRC Section 224 for up to $25,000 of "qualified tip" income (with no difference in the deduction limit for single versus joint filers), which will be in effect from 2025–2028.

To qualify for the No Tax on Tips deduction, tip income must meet the following conditions:

- The taxpayer must work in an occupation that "traditionally and customarily" received tips prior to 2025 (with the IRS being directed to provide a list of such occupations within 90 days of OBBBA's passage, which works out to October 2, 2025);

- The tips must be voluntary and not mandated as part of the service provided, with the amount determined solely by the payor; and

- The tips must not be earned through an SSTB as defined in IRC Section 199A (e.g., lawyers, accountants, and financial advisors are excluded, though musicians, artists, and entertainers – who often do receive tips – are also excluded).

The deduction is phased out starting at a MAGI of $150,000 for single or head of household filers, and $300,000 for joint filers, with the phaseout occurring at a rate of $100 per $1,000 of income over the threshold. Notably, the deduction itself – and not just the maximum allowable deduction – appears to be phased out once the threshold is reached.

Example 4: Ash is a single taxpayer with $200,000 of MAGI who earned $20,000 in tip income for the year.

Since her MAGI is $50,000 more than the threshold for her filing status ($150,000), Ash's tip deduction will be reduced by $100 × ($50,000 ÷ $1,000) = $5,000, giving her a total deduction of $20,000 − $5,000 = $15,000.

If an individual earns tips as part of a trade or business they own, their qualified tip deduction is limited to their net business income (i.e., gross business income minus other business-related deductions).

As noted above, the qualified tips deduction is a below-the-line deduction taken after AGI, but it is available regardless of whether the household itemizes or takes the standard deduction.

Qualified Overtime Compensation Deduction

Section 70202 of OBBBA's "No Tax On Overtime" provision, like "No Tax on Tips", doesn't exempt overtime compensation from income but instead creates a deduction under newly created IRC Section 225 for the amount of qualified overtime compensation received, effective from 2025–2028.

Unlike the qualified tips deduction, the deduction limit for qualified overtime does differ by filing status, with a $25,000 deduction for joint filers and a $12,500 deduction for all other filers. However, the phaseout rules for the overtime deduction are the same as for the tip deduction: The phaseout begins at a MAGI of $150,000 for single and head of household filers and $300,000 for joint filers, reducing the deduction by $100 for every $1,000 of MAGI above those levels.

The deduction would apply to the amount of overtime compensation paid above an employee's normal rate. For example, if an employee earns $20 per hour in base wages and $30 per hour for overtime, only the extra $10 per hour for overtime wages would qualify, not the $20 hourly base rate.

Example 5: Dorothy is an administrative assistant who earns $20 per hour in base wages and $30 per hour for overtime.

This year, she worked 20 hours of overtime, earning $30 × 20 = $600 total for these hours.

Of this amount, the portion corresponding to her base wage rate ($20 × 20 = $400) would be included in her taxable income, while the portion corresponding to her additional overtime pay ($10 × 20 = $200) would be eligible for the overtime deduction.

Like the tip deduction, the overtime deduction is a below-the-line deduction taken after AGI is calculated. It is available regardless of whether the taxpayer itemizes or takes the standard deduction.

As shown below, the two deductions for qualified tips and qualified overtime are structured nearly identically. The main difference is that the maximum deduction for qualified tips is the same for all taxpayers regardless of filing status, while the qualified overtime deduction differs between joint and other filers.

New Auto Loan Interest Deduction

The third major tax proposal that arose during the 2024 campaign – alongside the elimination of taxes on overtime wages and tips – was to make interest on auto loans tax-deductible. Consequently, Section 70203 of OBBBA includes a new deduction for "qualified passenger vehicle loan interest" that will be in effect from 2025 through 2028.

The deduction would apply to interest on loans used to purchase certain vehicles for personal use (i.e., not for business or resale). Specifically, eligible vehicles include new cars, vans, SUVs, pickup trucks, and motorcycles manufactured for operating on public roads and having a gross vehicle weight of less than 14,000 pounds. This means that RVs, ATVs, trailers, and any pre-owned vehicles are excluded in the final version of the law (even though they would have qualified under the original House proposal). Additionally, the vehicle must be assembled in the U.S. to be eligible for the deduction. While this rule includes a relatively broad range of makes and models, it could still create confusion for people who are unsure where their vehicle was assembled. (This can be verified by checking the vehicle's Vehicle Identification Number (VIN).)

Notably, the deduction applies only to interest on new loans taken after December 31, 2024. Interest on loans taken earlier would not be deductible. However, if an existing loan is refinanced in 2025 or later – without increasing the balance of the original loan – the interest on the refinanced loan qualifies. By contrast, taking out a new loan on a car that's already paid off would not qualify.

The rule doesn't restrict the number of loans eligible for the deduction, but it does cap the total amount of deductible interest at $10,000 per year (not indexed to inflation). Additionally, the deduction would phase out by $200 for every $1,000 (or portion thereof) of MAGI over the thresholds of $100,000 for single filers and $200,000 for joint filers. This means the deduction would be completely phased out for single filers with over $149,000 of MAGI and joint filers with over $249,000 of MAGI.

As with the qualified tip and qualified overtime deductions, OBBBA's new auto loan interest deduction is a below-the-line deduction that can be taken whether the taxpayer itemizes deductions or takes the standard deduction. If you're counting, that makes five new below-the-line (non-itemized) deductions introduced by OBBBA.

The plus side is that these deductions are available to taxpayers who don't itemize their deductions. With over 90% of taxpayers now taking the standard deduction rather than itemizing, it makes sense to structure these deductions primarily for middle-class taxpayers in a way that allows them to benefit.

The plus side is that these deductions are available to taxpayers who don't itemize their deductions. With over 90% of taxpayers now taking the standard deduction rather than itemizing, it makes sense to structure these deductions primarily for middle-class taxpayers in a way that allows them to benefit.

The irony, however, is that the standard deduction was originally created to offer an alternative to tracking and reporting a slew of individual below-the-line deductions on Schedule A. But as the standard deduction grew to cover nearly all households, the only way to create new deductions that people could actually benefit from was to put them outside of Schedule A. Which just restarts the cycle of adding more deductions for individuals to track and report, until eventually there's a renewed push to "simplify" the tax code.

The takeaway, regardless of one's opinion on tax policy, is that the host of new deductions (and alterations to existing deductions on Schedule A) adds significant complexity to many households' tax pictures. Even though software can easily calculate the taxes owed each year, actually planning – particularly for future years – becomes exponentially harder as more deductions, qualifications, and phaseouts come into play. There's also significant uncertainty around how long many of these rules will be in effect and whether the provisions scheduled to sunset in 2028 will be extended further. All of which is good for the advisors who familiarize themselves with the rules and help clients take advantage of them, but less helpful for individuals who simply want a clear idea of how their financial decisions will factor into their tax picture.

Child Tax Credit Increased And Indexed To Inflation

The Child Tax Credit had been set to decrease from the current $2,000 per qualifying child down to $1,000 with the sunset of TCJA. Instead Section 70104 of OBBBA permanently increases the credit to $2,200 beginning in 2025. Additionally, the credit will be indexed to inflation beginning in 2026, marking the first time in the Child Tax Credit's nearly three-decade history that it will automatically increase with the cost of living.

The Additional Child Tax Credit – the refundable portion of the Child Tax Credit, which, unlike the standard Child Tax Credit, can generate a refund even if the taxpayer owes no tax for the year – is not increased by the OBBBA. While the standard credit rises from $2,000 to $2,200, the Additional Child Tax Credit remains at $1,700 for 2025. Unlike the standard credit, however, the refundable credit was already indexed to inflation, so it will increase in line with the standard credit going forward.

OBBBA also maintains TCJA's income-based phaseout rules. Households with MAGI over $200,000 (single and head-of-household) or $400,000 (joint) will have the credit phase out by $50 for every $1,000 of AGI above those limits. These thresholds are not indexed to inflation, however, and would remain fixed at those levels unless changed by future legislation.

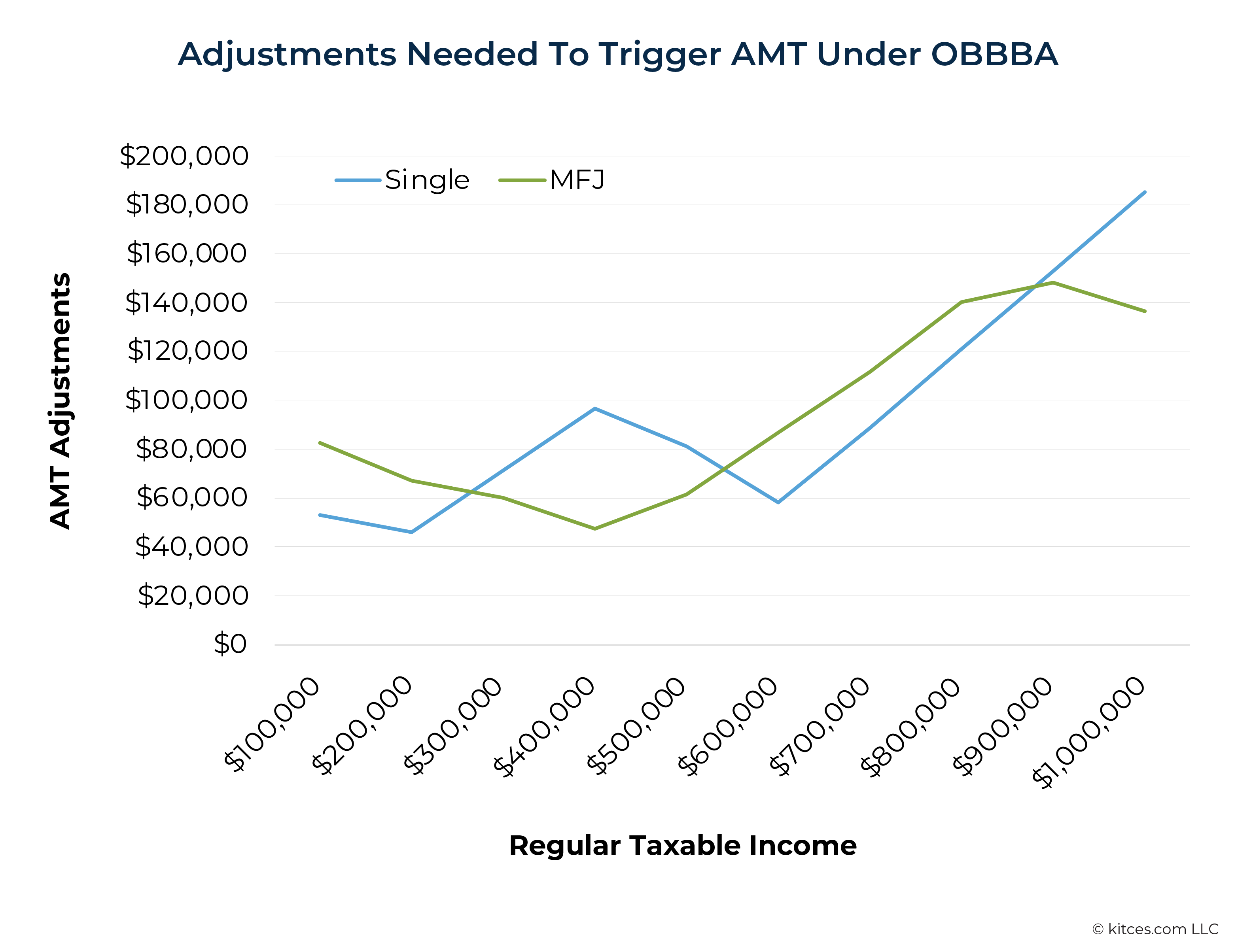

Alternative Minimum Tax Exemption Phaseout Thresholds Reduced

One of the less well-known impacts of TCJA was that it greatly reduced the number of households subject to the Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT). This was partly because TCJA eliminated personal exemptions and limited the SALT deduction to $10,000. Under prior law, both of these deductions were allowed under the regular tax system but disallowed under AMT, which created a bigger gap between regular taxable income and AMT income. Narrowing the gap meant fewer taxpayers were pushed into AMT liability.

However, the biggest drivers of this reduction in households subject to AMT were TCJA's substantial increase in the AMT exemption – up to $88,100 for single filers and $137,000 for joint filers for 2025 – and the much higher income levels of AMT income where those exemptions began phase out. Currently, the phaseout thresholds are $626,350 for single filers and $1,252,700 for joint filers. As a result of these changes, only about 0.1% of households currently owe AMT.

Under Section 70107 of OBBBA, the AMT exemptions from TCJA are permanently extended. However, starting in 2026, the AMT exemption phaseout thresholds will be reduced to $500,000 for single filers and $1 million for joint filers – effectively resetting those amounts to where they were when TCJA was first enacted in 2018.

Additionally, once a taxpayer's AMT income reaches the exemption threshold, the new law increases the AMT exemption phaseout rate to 50% of the dollar amount above the threshold, compared to the current 25%.

The result will be to moderately increase the likelihood of AMT exposure for certain taxpayers. As shown below, single filers with between $100,000 and $200,000 of regular taxable income will need between $40,000 and $60,000 of AMT adjustments – most commonly including the standard deduction, state and local taxes, and the difference between exercise price and fair market value on exercised Incentive Stock Options (ISOs) – to trigger AMT liability. That amount dips back down to about $60,000 of adjustments at around $600,000 of taxable income as the new exemption phaseout kicks in.

For married couples, the greatest risk of AMT exposure is between $300,000 and $500,000 of taxable income. And with the OBBBA increasing both the standard deduction and the SALT deduction limit, it will be easier for some households to reach these adjustment levels – and therefore be exposed to AMT – in the years to come.

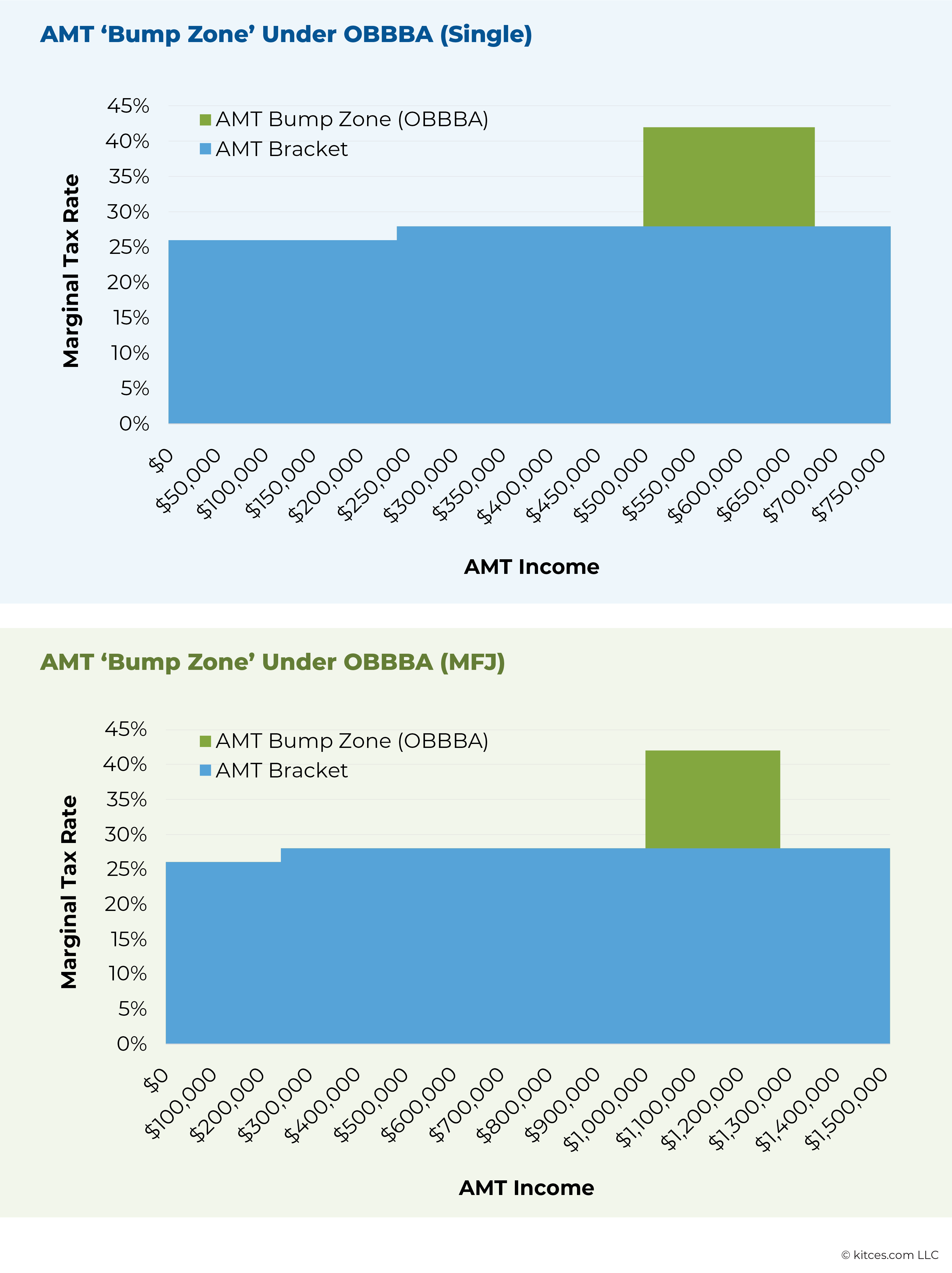

Additionally, the increased rate at which the AMT exemption phases out under OBBBA will create a narrower, but more pronounced, "bump zone" of higher effective marginal tax rates for households with AMT income within the exemption phaseout range. In essence, because every additional dollar of AMT income now reduces the exemption by 50 cents for taxpayers who will be by definition in the 26% AMT bracket, the effective marginal tax rate of income within the phaseout range is 26% × 1.5 = 42%!

As shown below, this "bump zone" will apply to single filers with AMT income between $500,000 and $676,200, and to joint filers with income between $1 million and $1,274,000.

Individuals who could be exposed to these bump zones after the new rules go into effect in 2026 will want to plan carefully to defer or avoid incurring additional AMT income. In particular, workers with unexercised ISOs may need to seriously consider exercising them before the end of 2025 to take advantage of the current, higher AMT exemption thresholds and the more gradual phaseout calculation. Even if exercising now exposes them to AMT this year, the impact of waiting until 2026 or later could be significantly worse.

Estate Tax Exemption Raised To $15M Per Person

One of the most significant provisions of TCJA from an estate planning perspective was its doubling of the gift and estate tax exemption in 2018, from $5.6 million to $11.2 million per person. The exemption has since grown to $13.99 million in 2025, meaning that a couple with up to $27.98 million of assets between them could pass away without being subject to estate tax. But with TCJA's sunset, the gift and estate tax exemption was set to decrease again by 50% at the end of 2025, creating rising concern among affected families and a flurry of estate planning moves to transfer assets out of their estates and use the higher exemption while it remained available.

Section 70106 of OBBBA, however, prevents the scheduled reduction and instead slightly increases the exemption to $15 million per person (or $30 million per couple) starting in 2026, with further inflation adjustments thereafter. This change will come as a relief to families with estates of over $15 million, who otherwise would have faced estate tax rates of up to 40% on the excess.

However, families who already made large gifts in anticipation of a lower exemption may start exploring ways to unwind those gifts – for example, by exercising decanting provisions to move funds into a trust better suited to the new legislative reality. It's worth noting that any actions taken today should also account for the possibility that a future Congress could again reduce the exemption.

New Eligible Expenses For 529 Plans

The new law expands the types of expenses eligible for tax-free distributions from 529 plans by broadening the definition of "qualified higher education expenses". In addition to the current allowance for K–12 tuition, the measure adds several new K–12-related costs and also introduces a new category of qualified expenses for certain postsecondary credentialing programs.

Expanded List Of K–12 Expenses

Section 70413 of OBBBA expands the list of K–12 expenses eligible for tax-free 529 plan distributions. Currently, the only K–12-related expense eligible for 529 plan purposes is up to $10,000 per year of tuition paid to a primary or secondary school.

As of OBBBA's enactment on July 4, 2025, however, the new law adds the following additional expenses for students enrolled in public, private, or religious schools:

- Expenses for curriculum materials, textbooks, instructional materials, and online education materials;

- Costs for tutoring provided outside the home, if the tutor is unrelated to the student and meets specific qualifications;

- Fees for standardized tests, AP exams, and college admission exams;

- Dual enrollment fees for postsecondary programs (e.g., college courses taken in high school); and

- Educational therapy costs for students with disabilities, including occupational, behavioral, physical, and speech-language therapies.

Additionally, OBBBA increases the annual limit for these types of expenses from $10,000 to $20,000 per year beginning in 2026.

The new rules would apply to any distributions taken after the bill's enactment – meaning that any of the above expenses incurred this year, regardless of whether they were incurred before or after the bill's enactment, may be reimbursed through 529 plan funds as long as the distribution also happens this year.

Postsecondary Credential Expenses

Along with the expanded list of K–12 expenses, Section 70414 of OBBBA allows 529 funds to be used for qualified postsecondary credentialing expenses. The new law includes three types of eligible costs:

- Tuition, fees, books, and any other expenses required for enrolling in a postsecondary credential program;

- Fees for exams required to obtain or maintain the credential; and

- Fees for continuing education necessary to maintain the credential.

Eligible credentials include those that are industry-recognized and accredited by major credentialing organizations, apprenticeships registered with the Department of Labor, occupational licenses issued or recognized by a state or the Federal government, and other postsecondary credentials as defined under Section 3 of the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act.

Notably for current or aspiring CFP certificants, the CFP marks appear to meet the definition of a recognized postsecondary credential, according to a CFP Board announcement. This means the costs of education and examination for attaining CFP certification, as well as the costs of continuing education for ongoing maintenance of the certification, could be paid with 529 plan funds under the new rules. It's less clear whether CFP Board's annual dues would also qualify, since the legislation doesn't explicitly name ongoing membership or administrative fees for maintaining a credential as eligible expenses.

(Slightly) Expanded Eligibility For HSA Contributions

The original House version of OBBBA included sweeping reforms to Health Savings Accounts (HSAs). Among other changes, it would have doubled annual contribution limits, ended common HSA eligibility 'traps' by allowing contributions to an HSA while covered by Medicare Part A or when a spouse participates in a health Flexible Spending Account (FSA), and expanded eligible expenses to include certain health club membership and fitness class fees.

However, the Senate removed most of these provisions, leaving only two significant HSA-related measures in the final law.

First, Section 71307 of OBBBA expands the definition of a High Deductible Health Plan (HDHP), which an individual must have to contribute to an HSA. Under the new rule, all "Bronze" and "Catastrophic" plans offered on Federal or state Affordable Care Act exchanges now qualify as HDHPs. Previously, not all of these plans met the official HDHP definition because they did not all satisfy both the minimum deductible and maximum out-of-pocket limit required for HSA eligibility.

Additionally, Section 71308 allows individuals to maintain HSA eligibility while covered by a direct primary care arrangement. Under these arrangements, individuals pay a flat monthly or annual fee to a primary care practitioner – capped at $150 per month or $300 per month if the arrangement covers more than one person – for their primary care services. The new provision clarifies that these arrangements will not be treated as disqualifying coverage, resolving previous uncertainty about whether they would make someone ineligible to contribute to an HSA.

"Trump Accounts" To Jumpstart Retirement Savings For Kids?

It's not uncommon for parents to want to help their children get a head start on their retirement savings, particularly given the potential for compounding tax-deferred (or tax-free, in the case of a Roth account) growth over many decades between childhood and retirement.

The challenge, however, is that existing options for parents to save on their children's behalf all have drawbacks of one kind or another. Retirement-focused accounts like traditional and Roth IRAs require the contributor to have earned income, meaning a child can't contribute to them (or have funds contributed on their behalf) until they have a job. Taxable custodial accounts like UTMAs or UGMAs are transferred in full to the child at the age of majority, with no way to ensure the funds are actually used for retirement as intended. And 529 plan funds are limited to qualified educational expenses (though up to $35,000 of 529 plan funds can now be rolled over to a Roth IRA if the 529 plan is open for at least 15 years, making this route more attractive).

Section 70204 of OBBBA creates a new alternative for starting retirement savings at an early age with a type of IRA dubbed a "Trump account", which can be opened and funded on behalf of any individual with a Social Security number from birth up until the year before the year in which they turn 18.

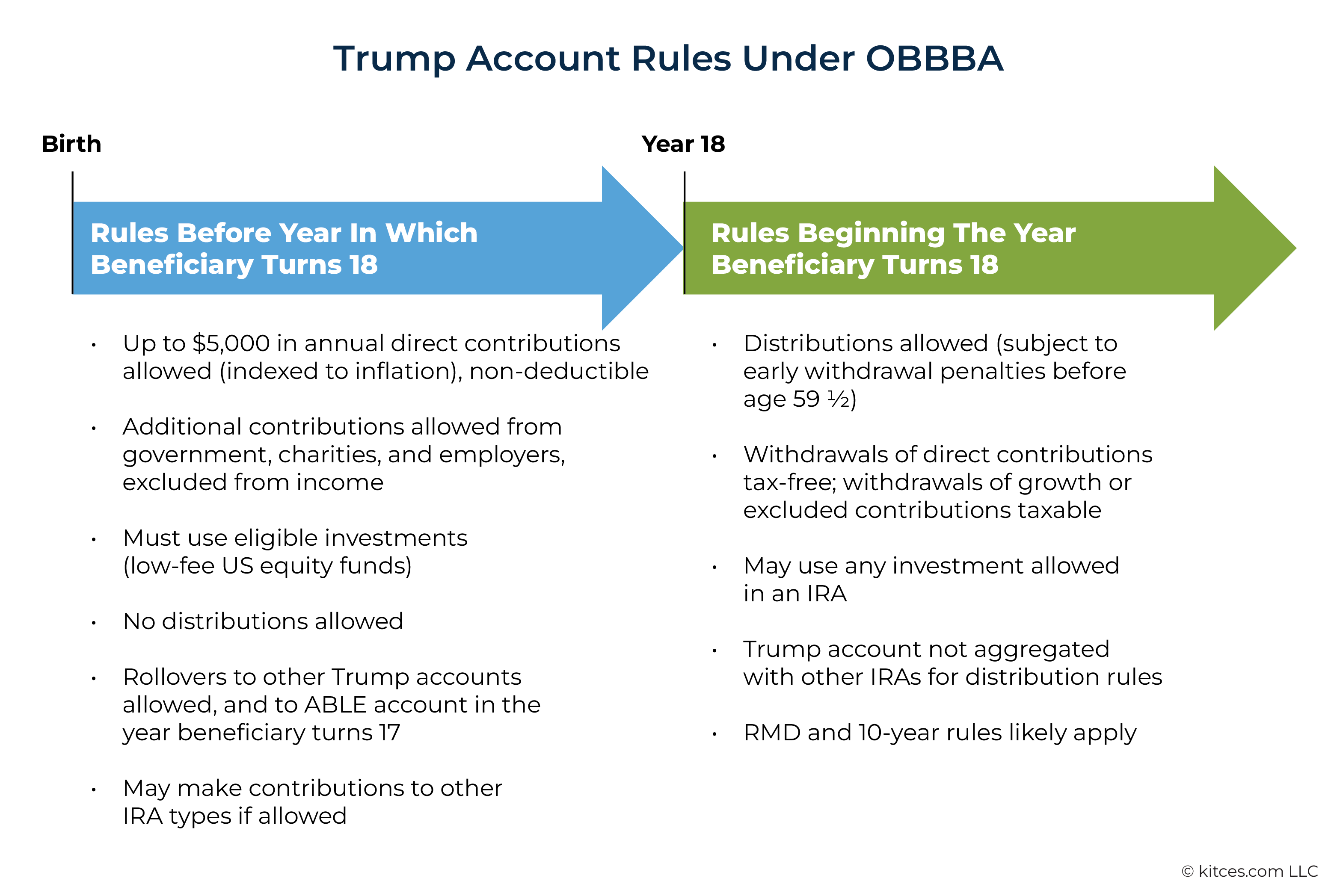

It's helpful to break down the rules for these accounts into two phases: prior to the year the beneficiary turns 18, and after.

Rules Prior To The Year The Beneficiary Turns 18

Starting in July 2026, one year after OBBBA's enactment, contributions of up to $5,000 per year (indexed to inflation in subsequent years) can be made to a Trump account on behalf of a beneficiary who has not yet reached the year in which they turn 18. Unlike a traditional or Roth IRA, there's no earned income requirement. Contributions made directly by a parent or other individual are not tax-deductible.

However, other entities – including Federal, state, and local governments and 501(c)(3) charitable organizations – can also contribute on a beneficiary's behalf, and those contributions do not count toward the $5,000 annual limit. Additionally, employers can contribute to a Trump account on behalf of an employee or any of the employee's dependents, subject to a $2,500 annual cap, also adjusted for inflation, which does appear to count against the $5,000 limit. Contributions from any of these sources, however, are excluded from the beneficiary's income.

If an individual is eligible to contribute to both a Trump account and a traditional or Roth IRA (i.e., they are under the age limit for Trump account contributions and meet the earned income requirements for IRA contributions), contributions to one do not reduce the amount that can be contributed to the other.

Investments in a Trump account are limited only to funds that track a qualified index, defined as the S&P 500 or any index composed primarily of U.S. equities. Market-cap based indexes (e.g., U.S. small cap) are allowed, but sector- or industry-weighted indexes (e.g., tech stock funds) are not. The funds must also be unleveraged and have annual fees no higher than 0.1%.

No distributions can be made from a Trump account until the year in which the beneficiary turns 18, except to roll over the entire account balance into a 529A ABLE account in the year the beneficiary turns 17, assuming the beneficiary qualifies due to disability. Trump accounts may be rolled over into other Trump accounts at any time, provided they are rolled over in their entirety, but they cannot be rolled into other types of IRAs.

If the beneficiary dies prior to the year in which they turn 18, the account loses its tax-deferred status. The entire balance (minus any direct contributions) becomes taxable to the designated beneficiary, or to the account beneficiary's final tax return if no beneficiary is named.

Rules Starting In The Year The Beneficiary Turns 18

Once the beneficiary of a Trump account reaches the year in which they turn 18, the account starts to look much more like a standard traditional IRA, though it contains a mix of after-tax dollars (direct contributions) and pre-tax dollars (contributions from other sources that were excluded from gross income plus all growth). Most notably, the IRA distribution rules requiring owners to wait until they reach age 59 1/2 to make penalty-free withdrawals would presumably still be in effect. The "eligible investment" rules no longer apply and the beneficiary can invest the funds in any way allowed within an IRA.

It's still unclear whether a Trump account could be rolled into a standard IRA or converted to a Roth IRA once the beneficiary turns 18. Notably, Trump accounts will not be subject to the IRA aggregation rules under IRC Section 408(d)(2), which means there may be advantages to keeping them separate from other IRAs – for example, to avoid taxable conversion under the IRA pro-rata rules when making backdoor Roth contributions. But for a young adult in a relatively low tax bracket, there also could be significant benefits to converting the whole account to a Roth IRA at age 18, making any future growth tax-free. More guidance will be needed to clear up the questions around how Trump accounts will interact with standard traditional and Roth IRAs.

The law is also unclear on whether other IRA rules – including Required Minimum Distributions (RMDs) or the 10-year post-death distribution rule under the SECURE Act – will apply after the year the beneficiary turns 18. The assumption is that they will, since the law states that Trump accounts are generally treated as IRAs under Section 408(a) unless otherwise specified. However, since there are many years until the first beneficiaries reach RMD age, additional clarification may emerge over time.

'Pilot Program' $1,000 Contributions

To jumpstart the use of Trump accounts, the new law institutes a pilot program in which parents can elect to have a $1,000 credit paid by the U.S. government into a Trump account on behalf of an eligible child (defined as any U.S. citizen born in 2025, 2026, or 2027).

It's still unclear how the mechanics of this will work. For example:

- Will the government open new Trump accounts on behalf of eligible individuals who don't yet have an account on their behalf?

- Will the election be made on the parents' tax return, or will a separate form be required to claim the credit?

- How will parents of children born in 2025 elect the credit if no contributions can be made before July of 2026?

Presumably, additional guidance will clarify how parents can claim the credit for children eligible under the pilot program.

From a planning perspective, while it's good in theory to have an account designed to address the limitations of existing options for helping kids start retirement savings, in practice it's worth questioning whether another account type – complete with its own unique rules and restrictions – is really necessary. Congress could have simply relaxed the income requirements for IRA contributions for children under age 18 rather than creating and funding a brand-new structure.

Could the new Trump accounts instead be a first step in a broader plan, such as privatizing Social Security benefits? If the program to create privately owned, government-funded retirement accounts beginning in childhood proves successful, a future step could involve directing Social Security payroll taxes into the same accounts to be invested and distributed at the individual's discretion. This would effectively shift the responsibility for providing a baseline level of retirement income from the government to individuals.

This has long been a priority for some conservative policy makers. For example, 20 years ago, then-president George W. Bush proposed a similar plan to fund personal retirement accounts in his 2005 State of the Union speech. Although his proposal was unpopular and never taken up by Congress due to public backlash around the idea of 'privatizing' Social Security, it's possible that the new Trump accounts represent a quieter approach toward a similar strategy. Time will tell, but the fact that these accounts closely resemble Bush's proposed personal retirement accounts suggests that they could have similar intent.

Qualified Opportunity Zones Extended

The original TCJA created a new type of investment known as a Qualified Opportunity Fund (QOF). These funds allowed investors to pool capital into Qualified Opportunity Zones (QOZs), which are low-income geographic areas designated by state governments.

QOFs offered the potential for significant tax benefits, particularly for high-income investors. Individuals could sell appreciated investment property (e.g., stocks, funds, or real estate) and reinvest the gains into a QOF. That gain would then be deferred until the earlier of December 31, 2026, or the date the QOF was sold or exchanged. This effectively allowed for up to eight years of gain deferral for QOFs created in 2018.

Additional incentives were available for investors with longer holding periods:

- A 10% basis step-up on deferred gain after five years;

- An additional 5% step-up for those who held their QOF for more than seven years, allowing up to 15% of the deferred gain on the original investment to be permanently excluded from taxation; and

- Complete exclusion of post-investment appreciation if the QOF was held for more than 10 years.

Section 70421 of OBBBA creates a more permanent version of the QOF program, but with a narrower scope and updated rules.

Under the new measure, states will be allowed to designate a new round of QOZs every 10 years starting in 2026. The definition of low-income areas will be slightly more restrictive: qualifying communities must have a median income below 70% of the median income for the state or metropolitan area where they're located, rather than 80% under the original law).

Starting in 2027, investors can defer capital gains by reinvesting them into a QOF, with deferral lasting until the earlier of when the property is sold or exchanged or five years after the original investment.

As with the original program, investors who hold a QOF for at least five years will receive a 10% basis step-up on the deferred gain. However, investments in a QOF that invests at least 90% of its assets in rural QOZ property would receive a 30% step-up. In contrast to the original QOZ program, there is no additional 5% step-up for QOFs held for more than seven years. As before, any gains attributable to the original deferred gain will be excluded from taxation if the QOF is held for more than 10 years – though any further gains after 30 years would become taxable.

Notably, all of these proposed changes apply only to new QOF investments made starting in 2027. For existing investors whose deferred gains are scheduled to be recognized in 2026, there's no way to extend that deferral further; those gains would still become taxable as planned.

Repeal Of Clean Energy Credits

One of the few provisions in the House Republican proposal aimed at increasing taxes on individuals is the rollback of several 'clean energy' tax credits originally introduced under the Inflation Reduction Act in 2022. These credits were originally scheduled to sunset between 2032 and 2035. These credits include:

- The Clean Vehicle Up to $7,500 for a new electric vehicle and $4,000 for a used one. Sections 70501 and 70502 of OBBBA, respectively, terminate these credits for vehicles acquired after September 30, 2025.

- Alternative Fuel Vehicle Refueling Property Credit. Up to $1,000 for electric vehicle charging equipment installed at a taxpayer's personal residence. Section 70504 terminates this credit for property placed in service after June 30, 2026.

- Energy Efficient Home Improvement Credit. Up to $1,200 toward the cost of energy-efficiency improvements (e.g., windows, doors, insulation, or heating and cooling equipment, and home energy audits). Section 70505 terminates this credit for property placed in service after December 31, 2025.

- Residential Clean Energy Credit. Up to 30% of the cost of purchasing or installing solar panels, wind power, geothermal heat pumps, or fuel cell equipment. Section 70506 terminates this credit for expenditures made after December 31, 2025, regardless of when the property is placed in service.

To the extent that clients have plans to buy an electric vehicle or undertake any of the above home energy improvements, it will be important to make sure the purchases or work are complete by the new deadlines to remain eligible for the credits.

Other Provisions

There are a host of other provisions in the final legislation that are worth noting:

- Qualified Small Business Stock (QSBS) – Section 70431: Increases the maximum 1202 capital gain exclusion from $10 million to $15 million for QSBS acquired after July 4, 2025. This section also partially excludes gain from QSBS acquired after July 4, 2025:

- 50% exclusion if held between 3 and 4 years

- 75% if held between 4 and 5 years

- 100% if held for 5 years or more

QSBS acquired prior to July 4, 2025, must be held at least 5 years to exclude any gain.

- Student Loan Debt Discharged Due To Death Or Disability – Section 70119: Permanently extends TCJA's exclusion from income for student loan debt discharged due to death or disability (but only for students with a valid Social Security number).

- Student Loan Payments Under Employer-Provided Borrower Assistance – Section 70412: Permanently extends TCJA's exclusion from income of up to $5,250 annually for student loan payments made under an employer's borrower assistance program, with annual inflation adjustment beginning in 2027.

- Adoption Tax Credits – Section 70402: Makes up to $5,000 of the adoption tax credit refundable, indexed to inflation, beginning in 2025.

- Charitable Contributions Funding K–12 State Scholarships – Section 70411: Creates a tax credit of up to $1,700 for contributions to charitable organizations that fund K–12 scholarships within their state, beginning in 2027.

- Bonus Depreciation of Business Property – Section 70301: Permanently restores 100% bonus depreciation for business property placed in service after January 19, 2025.

- Section 179 Deduction Limits – Section 70306: Increases Section 179 deduction limits to:

- $2.5 million in aggregate total cost (from $1 million)

- $4 million in total Section 179 property (from $2.5 million)

These increases are adjusted for inflation starting in 2025.

- U.S. Research Expenses – Section 70302: Permanently allows 100% expensing of research and experimental costs incurred for research in the U.S.. Taxpayers can retroactively elect this treatment for expenditures from 2021–2024, or deduct unamortized expenditures in 2025 or over 2025–2026.

- Excess Business Loss Limitation – Section 70601: Makes the excess business loss limitation permanent, resetting the amount to $250,000 (single) or $500,000 (joint) starting in 2026, with inflation adjustments thereafter.

- 529A ABLE Account Contributions – Section 70115: Permanently extends the 529A ABLE account rules allowing contributions up to the current gift exclusion limit plus the beneficiary's compensation up to the Federal poverty line.

- Saver's Credit for ABLE Account Contributions – Section 70116: Extends the Saver's Credit to ABLE account contributions starting in 2026 and limits the Saver's Credit exclusively to ABLE account contributions starting in 2027. The credit amount increases to $2,100 beginning in 2027, with inflation adjustments thereafter.

- Rollovers From 529 To 529A ABLE Accounts – Section 70117: Permanently extends TCJA's provision allowing tax-free rollovers from 529 plans to 529A ABLE accounts.

- Child and Dependent Care Credit – Section 70405: Increases the applicable percentage of care expenses used to calculate the Child and Dependent Care Credit starting in 2026 to:

- Households with AGI under $15,000: 50%

- Households with AGI between $15,000 and $75,000 (single and head-of-household) or $150,000 (joint): Reduced from 50% by 1% for each $2,000 of AGI over $15,000, down to a minimum of 35%

- Households with AGI over $75,000 (single) or $150,000 (joint): Reduced from 35% by 1%, for each $2,000 (single) or $4,000 (joint) over those thresholds, down to a minimum of 20%

- Reporting Limits for 1099-K Third-Party Payment Processors – Section 70432: Repeals the Section 6050W(e) de minimis threshold of $600 for 1099-K information reporting (enacted in the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 but never implemented) and restores the prior limit of $20,000 and 200 transactions starting in 2025.

- Reporting Limits For Business Payments – Section 70433: Increases the Section 6041 threshold of $600 for information reporting of business payments (1099-NEC, 1099-MISC, etc.) to $2,000, adjusted for inflation, starting in 2026.

- Gains On Qualified Farmland Sale – Section 70437: Allows gain from sale of qualified farmland to be spread over four annual installments if it is sold to a "qualified farmer" (i.e., not a developer).

- Overseas Remittances – Section 70604: Imposes a 1% tax on all remittances sent overseas, affecting U.S. taxpayers who send funds to family members and other individuals overseas.

- Employee Retention Tax Credit (ERTC) Penalties – Section 70605: Imposes a $1000 fine per occurrence for ERTC promoters who fail to comply with due diligence requirements imposed under Section 6695(g). Also extends the statute of limitations on ERTC refund claims to six years after the later of the return filing date or credit claim date.