Executive Summary

The traditional view of financial advisors is that they are highly motivated by the income potential and upside opportunity of being a financial advisor… and thus why the compensation system for most advisory firms is still predicated on an “Eat What You Kill” performance-based approach. For those who have the business development skill set, and a motivating desire to be rewarded for it, an advisory career can be incredibly lucrative.

However, when evaluated in our recent Kitces Research study of “What Financial Advisors Really Do,” it turns out that the financial rewards of being a financial advisor are actually not the primary motivator after all. Instead, the primary drivers for doing comprehensive financial planning are an intrinsic desire to help and serve others and to apply one’s talents and interest in personal finance. Which happens to also be financially rewarding… though even then, the income potential of being a financial advisor is more about work/life balance and lifestyle flexibility than just the extrinsic motivation of the income potential itself.

Which is significant, because it suggests that the financial services industry at large may not actually be communicating the right messages to make financial planning an appealing career choice in the first place. Simply put, in an industry dominated by money, it turns out that the mentality of a financial planner truly is about helping others with their money, more so than simply being financially rewarded for the advice and getting clients in the first place.

On the other hand, the data suggests that over time, financial advisors who have spent some time in the industry have largely managed to find the pathway that best fits their natural style. Advisors who are more interested in upside income potential do tend to either build their own advisory firms (hiring the staff and support infrastructure around themselves to grow larger) or join large firms where they can pursue a path to partnership. While those most interested in work/life balance are more inclined towards being – and remaining – solo advisors, where they can have ultimate control. And those who really are the most extrinsically motivated by the income potential itself – and not necessarily the desire to serve – are more likely to stay in commission-based channels where such motivators are best rewarded.

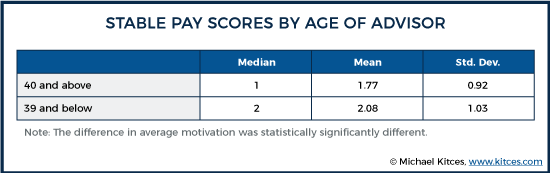

The key point, though, is simply that it’s important to understand the true motivators for financial advisors, both for the industry to attract more next-generation talent to close the talent gap, and also for individual advisory firms that want to attract and retain talent. Because when the primary drivers of motivation are intrinsic – a desire to apply one’s own personal interest in personal finance, combined with a desire to help and serve others – offering too much extrinsic motivation, in the form of variable compensation and bonuses, can actually demotivate financial advisors from doing their best work for clients! Especially as a growing number of next-generation advisors are increasingly showing a motivational preference for stable pay over upside income potential anyway!

It is an understatement to say that financial planning is a tough industry for hiring – questions continually circulate about having enough new talent. Further, the first hires (and the following) are crucial for so many things: growth, spreading responsibilities around, and, one day, succession planning.

What is more, we already know that hiring based on “skill” is certainly not the only and arguably not the most important metric to consider. Caleb Brown, the founder of New Planner Recruiting, suggests hiring for attitude. As a consultant myself with a background in industrial/organizational psychology, I absolutely agree. When making hires, you want to strike a balance between skill and other personal attributes.

The starting point, though, is simply to understand what motivates a prospective financial advisor in the first place. Because if you can’t appeal to their fundamental motivators, it will be more difficult to attract – and almost impossible to retain – that talent anyway.

Understanding Intrinsic Vs. Extrinsic Motivation

Research in the field of psychology has found that there are two fundamental types of motivation: extrinsic and intrinsic.

Extrinsic motivators are a means to an end, such as taking action in an effort to earn money, power, or other externally-granted outcomes. Intrinsic motivators are goods unto themselves, that we draw upon internally, and are recognized as coming in three flavors: experiential (e.g., playing music for the personal joy of playing music), values (a motivation to take an action for a belief in fairness and “doing what’s right”), and personal goals/achievement (feeling motivated to run out of a desire to achieve the goal of running a marathon).

Extrinsic and intrinsic motivations often work hand-in-hand with one another, acting on different features of a relationship. For instance, in the workplace, employees are paid a salary for their work (a transactional contract that provides extrinsic financial motivation), and at the same time employees may also establish relational and personal contracts with their work (love making financial plans to help clients, love being a part of a company that helps people, want to attain the CFP certification to feel they have mastered their professional domain).

The Intrinsic Vs. Extrinsic Motivations of Financial Advisors

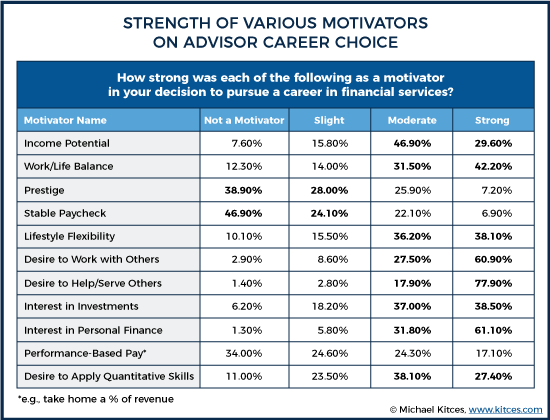

To get a handle on what motivates financial planners in particular, the Kitces Research team asked financial advisors, as part of our 2018 study on “What Financial Planners Actually Do,” the question: “How strong was each of the following as a motivator in your decision to pursue a career in financial services?” And provided a list of both intrinsic and extrinsic factors, from income potential and prestige, to a desire to work with others, a personal interest in personal finance, or to apply one’s own quantitative skills.

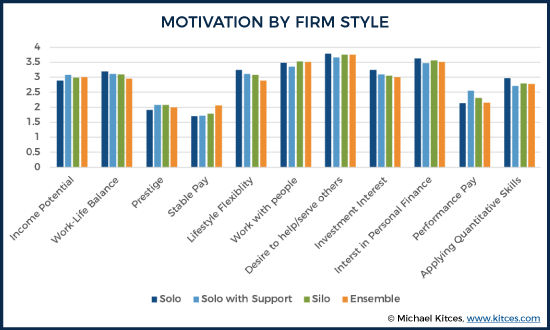

As indicated in the chart below, advisors have a wide range of motivations, including income potential, work/life balance, lifestyle flexibility, desire to work with others, an interest in investments, an interest in personal finance, and a desire to apply quantitative skills. Although notably, of the driving motivators, the highest was the desire to work with people, and an interest in personal finance but not necessarily regarding investments or applying quantitative skills in particular (i.e., the motivation of advisors seems to be more about “helping people with their money” in general). And even after that, the next tier of motivators was more about work/life balance and lifestyle flexibility, rather than “just” the income potential of being a financial advisor.

2

2

Perhaps not surprisingly, having a stable paycheck was not a motivator for financial advisors (given that few such jobs have existed historically, most who would have wanted a stable paycheck wouldn’t have chosen the advisor career in the first place), though advisors do seem torn on their feelings toward performance-based pay in general.

The key point, though, is that when it comes to the driving motivators of financial advisors, it’s actually helping people (and specifically helping them with their money) first, work/life balance and lifestyle flexibility second, and income third (though income was a material motivator nonetheless).

Financial Advisors See Money As Both The Means And The End

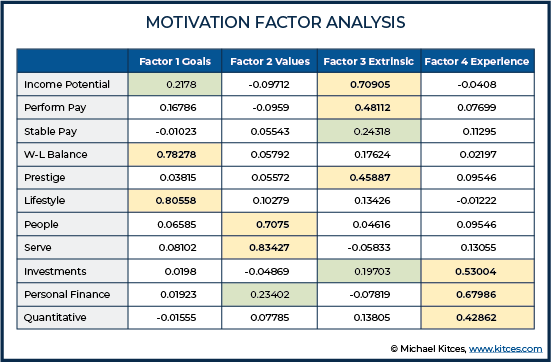

Traditional motivation research would suggest that financial advisors are primarily intrinsically motivated, as helping people (with their money) is a classic Values intrinsic motivator. Although at the same time, financial advisors did show extrinsic motivation as well – towards the income potential of being a financial advisor – though their extrinsic motivators do appear somewhat split (as advisors were motivated by income potential overall, but not necessarily performance pay as a means to get there). Accordingly, we decided to test and see whether the typical intrinsic and extrinsic motivation clusters hold true for financial advisors in particular.

To delve deeper, we did a factor analysis (which lumps observed variables - i.e., the questions we asked - together based on how they actually clustered in practice) to see if financial advisors’ motivational patterns are different than the typical intrinsic and extrinsic motivational factors. Our expected motivational groupings were:

- Extrinsic: income potential, stable paycheck, performance pay, and prestige

- Intrinsic Experiential: interest in investments, personal finance, and the desire to apply quantitative skills

- Intrinsic Values: serving/helping individuals and working with people

- Intrinsic Personal Goals: work/life balance and lifestyle flexibility

And as it turns out, advisors’ motivations did largely align to the traditional way these motivators are categorized! But with a few notable nuances, which may help to further clarify what makes it appealing to be a financial advisor.

As the results show in the table below, there are strong clusters of motivators around Intrinsic Personal Goals (work-life balance and lifestyle flexibility), Intrinsic Values (a desire to serve others), Intrinsic Experiences (applying our interest in personal finance, investments, and quantitative skills), and a set of Extrinsic motivators (income potential, performance pay, and prestige).

Notably, though, the “Stable Pay” motivator doesn’t have a particularly strong relationship to any of the categories! Perhaps not surprisingly, it does connect most closely to the other Extrinsic (typically-compensation-related) motivators, but far less so. Though given the historical context of the industry, this may simply be explained by the fact that in the past, the only path to becoming a financial advisor was an “Eat What You Kill” environment of getting your own clients, from scratch, on Day 1. Which means those who highly valued Stable Pay – which financial advisor jobs of the past rarely offered – probably wouldn’t have stuck around to be financial advisors (and show up to take our research survey!). On the other hand, the rise of “employee advisor” roles that have less of a business development obligation may be slowly shifting this landscape; for instance, amongst advisors under age 40, Stable Pay was at least a slight motivator, compared to advisors over 40 it was very clearly not a motivator (because if it were, they probably wouldn’t have stuck around in the financial advisor career when they started 20+ years ago!).

On the other hand, it’s also striking to see how the motivator categories connect to each other. For instance, the extrinsic factor of Income Potential also loaded with a 0.2 weighting (which is modest but non-trivial) in the Personal Goals area, suggesting that for advisors, income potential is motivating not only for its own sake, but because it can help support/fund the Personal Goals of work/life balance and lifestyle flexibility. Similarly, while an interest in personal finance and investments were primarily Intrinsic Experiential motivators, the Personal Finance interest also tied to the Values motivator, and the Investment interest also tied to the Extrinsic motivators. Which suggests that financial advisors both find money personally interesting and enjoyable to work with others on. And an advisor’s interest in investments is not only for the intellectual experience but also the opportunity to apply the skills to their own growing wealth, too!

More generally, though, it’s also notable that as a whole, financial advisors are very intrinsically motivated. It’s not just (or even primarily) about the income potential. Which is important both because it’s difficult to succeed as a financial advisor and takes a lot of perseverance – for which intrinsic motivation helps. But also because from an employer perspective, intrinsic motivators are actually the secret sauce for keeping employees happy (as extrinsic motivators can become a slippery slope that loses motivational value over time).

Financial Advisors Are Self-Selecting Into The Industry Paths That Fit Their Own Motivators

While the data suggests that financial advisors are not motivated primarily by earning potential alone, this does not mean that money is not important. And in fact, when evaluating advisors’ extrinsic financial motivators by the types of advisory firms they build or join, it turns out that some advisors appear to be very keen to climb the “corporate ladder” of opportunity… while others quite deliberately choose the financial rewards and opportunities of small firms, instead.

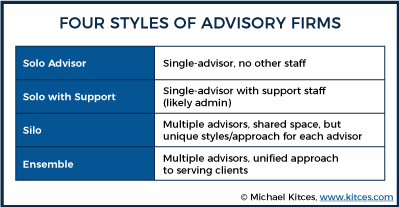

At a high level, we can segment advisory firms into four different types of firm styles – those who join large Ensemble firms (with multiple advisors and a unified approach to serving clients), a Silo approach where advisors join a platform that provides shared space and resources, but each advisor serves his/her own clients his/her own way, standalone solo advisors (who operate purely as solos in their own firms), and solo advisors who hire their own support infrastructure (e.g., leveraging themselves with their own administrative or paraplanner staff).

And the reason these distinctions in firm styles matter is that advisors in different firm structures exhibit materially different motivators (and the financial/income results that follow).

For instance, solo advisors appear to be less motivated by performance pay, when compared to advisors in ensemble firms. Which suggests that solo advisors tend to choose to be solo because they want the flexibility to live a certain lifestyle (and have control over their own work/life balance). Whereas advisors who were motivated by performance pay sought out a larger (ensemble) firm which could offer that upside potential (and had formalized the "rules" to climb the corporate ladder and achieve those outcomes).

However, that’s not to say that advisors who start solo firms are solely motivated by their work/life balance and income flexibility. In fact, as it turns out, the advisors most motivated by performance pay also chose the solo firm route – but then built up a staff infrastructure around themselves, and shifted into the “solo with support” model where they could better leverage themselves. Or stated more simply, advisors who don’t care as much about making a lot more money simply stay solo and enjoy their flexibility and work/life balance. Those who do want to make more money hire staff and deal with managing people in order to leverage themselves and grow further financially.

Notwithstanding the desire of more financially-motivated solo advisors to hire staff and leverage themselves, though, the data still showed that advisors in smaller firms (both standalone solos, and those with support) place a statistically significantly higher motivation on work-life balance when compared to advisors in ensemble firms. Or stated more simply, advisors who want more pay either grow the firm themselves or move to a bigger firm, while those who have a stronger preference for work-life balance will tend to do so in their own firm (rather than a larger firm they don’t control). On the other hand, it’s notable that none of the primary motivators drove advisors towards the “Silo” model, most common in the independent broker-dealer environment… which perhaps helps to explain why advisors have slowly but steadily left the broker-dealer channel as their success grows.

On the other hand, the advisors who do self-select into ensemble firms don’t only appear to place a premium on their income potential. A material subset of them also placed a higher emphasis on stable pay (far more so than any/all the other work environments: solo, solo-support, and silos). This may seem contradictory – that ensemble advisors are placing premiums on stable pay and performance pay – but it may simply be a proxy for the way that larger firms tend to have more structured incentives. In other words, larger firms tend to have more stable pay options, and more formal upside growth paths, as a part of the formalized career paths that emerge in larger firms. To that point specifically, we also found that associate advisors placed a statistically significantly higher premium on stable pay when compared to lead advisors and executives of advisory firms. Advisors who are attracted to that kind of career-advancement structure – whether for the stability or the upside – appear to be attracted first and foremost to the structure itself.

From a competitive perspective for talent, recognizing these motivators is also important, especially for large firms looking to hire talent. As it suggests that for large firms to compete for top talent, it may be especially important to actually have formalized career track opportunities. As the very structure of the career tracks themselves appears to be their greatest appeal (from a motivators perspective), even as different advisors may differently choose the firm for its structured stability, or its structured upside potential (e.g., a path to partnership).

Overreliance On Extrinsic Motivators And Self-Fulfilling Prophecies

Financial advisor motivations matter not only because they impact what channels advisors choose to join, and what business models they join or build around themselves, but also because motivators are what employers must connect to in order to motivate their employees.

Though for employers, the message sent via the “rewards” being offered, and favoring one type of motivation over another, can and does lead to what is known as the “crowding-out” effect – attention given to X motivation crowds-out the attention that may have been given to Y motivation. Which means it’s especially important to consider what motivators are being appealed to. For example:

Sam is a relatively new and excellent financial planning hire. Sam loves the clients and gets a tremendous sense of achievement and pride from serving them well.

Sam’s firm has decided to introduce a bonus system that will provide more compensation for bringing in new assets. Sam interprets this new bonus system to mean that to impress the boss what matters most is assets, not necessarily relationships, as assets are what is being monitored.

The end result is that, over time, Sam becomes more interested in the client’s assets than the clients themselves, and the financial reward over customer satisfaction. Which means not only does Sam lose his client-centric focus… but Sam’s intrinsic motivation and the psychic rewards he enjoyed from serving his clients well has also been eroded.

Such outcomes are not as far-fetched as some might think. In fact, our research found that commission-based advisors do have a statistically significantly lower motivation to serve clients (where the financial rewards are greater for finding the next, new client instead), when compared to those advisors working in an AUM structure (where the recurring revenue nature of the model more directly favors ongoing service to clients). In other words, paying advisors on commission may be “crowding out” what may have been the advisors’ (perhaps) original goal of serving clients. On the other hand, this finding could also simply mean that more money-motivated financial advisors choose to stay in commission-based channels where their financial focus is more quickly rewarded, whereas more service-oriented advisors are moving to the RIA channel instead. Either way, though, the key point is that rewards matter and can either attract people with certain motivators – or even shift their motivators to align with the rewards available where they are.

Notably, the key point is not necessarily that financial bonuses and rewards should never be paid. But at a minimum, it’s crucial to recognize that motivation and its influences have a much, much more nuanced relationship. Bonuses do not mean always or necessarily mean an erosion of intrinsic motivation. Nonetheless, when everyone just starts to expect rewards, eventually it can reach an endpoint where they won’t be motivated to do anything until a (new) reward is offered.

Implications For Managing Motivators Of Advisory Firm Employees

Another way to think about the divides between types of motivators is to consider the outcomes the firm is trying to achieve in the first place. Is the advisory firm trying to be growth-centric, or customer-service centric? Don’t over-think it, as there is no “right” answer. And some firms try to be in a place where both growth and customer-service really matter. Still, though, one path tends to command the greater focus – and the rewards and incentives to drive those results.

A company may be more growth-centered for any number of reasons (and again, growth-centered does not mean that you do not care about customer service). The firm may be focused on growing because it is a new firm. It may be focused on growing because there’s a need to make up the revenue cost of a new hire. The firm may be focused on growing because there’s a new office (and more rent overhead). Any of these are acceptable and great. And extrinsic rewards can be an effective way to motivate for growth. In this case, the biggest thing that matters when it comes to your reward system is actually the timing of the reward.

Consider the outcomes of a recent study from Woolley and Fishback, who found that long-term future rewards are usually extrinsic (e.g., “I want to make more money”) and that many short-term, instant rewards along the path to an extrinsic goal are intrinsic (e.g., “I learned a new skill that is related to making more money in the future – but for now makes me feel good about myself right now”). As such, when it comes to committing to and sticking with a long-term goal, immediate intrinsic rewards do a better job at increasing and sustaining motivation for the future goal by strengthening the activity-goal association, over just using extrinsic rewards. Thus, if growth is the focus – and depending on how much growth we are talking about is a long-term, future goal, consider giving intrinsic bonuses more frequently, such as quarterly and/or even “spot” bonuses.

Intrinsic-related bonuses can be time off of work, tickets to a concert, membership to the symphony… think “experiential.” Another important consideration when giving an intrinsic bonus is how it is given. You can certainly give the gift to them privately, with a nice note expressing your appreciation and acknowledging their hard work, but you might also consider giving the “bonus” in front of co-workers, publicly congratulating them on their success. The famous Vince Lombardi said, “Praise in public; criticize in private” - it feels good to be recognized in front of one’s peers, and praise like this can feel especially good for those advisors that are motivated by prestige!

On the flip-side, if your business goals are more customer-service centric, consider monetary and non-monetary rewards for activities outside of rainmaking. For example, if a client gives a referral – this is not only a traditional opportunity for new business but also an indication that this client loves their financial advisor. And firm owners can reward the advisor with a spot bonus for the implied client satisfaction. The spot bonus can be monetary, but again, it can also be an extra day off or some other personally relevant reward. The important thing is that firm owner must let the advisor know (ideally along with the rest of the team), that this “reward” is not because the firm may get a new client (i.e., new assets), but because the referral was made in the first place. Drive home the point that the firm cares and rewards those advisors who make their clients feel so good that they recommend others to the firm (regardless of the new referral panning out or not).

Other tactics to drive greater customer-service-centric culture might include instituting a firm-wide bonus structure based on customer service, and doing yearly customer service satisfaction surveys (e.g., at yearly-review meetings or via a short email survey). The firm may set a goal to have 90% customer satisfaction, and when that goal is reached (or the goal is consistently reached), all employees of the firm receive recognition and reward for a job well done.

Aligning Incentives To Advisor Motivators Requires Deeper Knowledge Of The Firm’s Advisors

An underlying theme that’s also important to recognize with this approach is that in order to give more personalized bonuses related more directly to an employee’s intrinsic experience, values, and personal achievement motivators – the firm must actually know what its employees want and need in the first place. Thus, almost regardless of motivation type and firm goals, it is vitally important that firm owners take the time to get to know their employees at an individual level and be willing to co-create a 5-year or a 10-year plan to get employee and the company’s goals in alignment.

As an example of why or how it can be important to know your employees, let’s consider some general, and interesting things we know about advisors’ personalities. Advisors are very conscientious people, and when we looked at the connection between conscientiousness and motivation, we find that motivation had a negative relationship with income potential, work-life balance, and lifestyle flexibility. In other words, the good news is that advisors are very conscientious of and mindful of their clients; the bad news is that they sometimes do so to the point of their own (not-happiness-inducing) self-sacrifice. And this “workaholic on behalf of clients” tendency can be a real challenge, given that over 70% of advisors indicate work-life balance and/or lifestyle flexibility as either a moderate motivator or a strong motivator for pursuing a career in financial planning in the first place!

Another important finding stems from advisors being rather agreeable individuals. Agreeableness in advisors was negatively correlated with income potential, performance pay, and prestige. In other words, even if they wanted more money (which most do, based on our analysis of advisor motivations), many don’t ask for it. Agreeable people do not like to “rock the boat” and, in turn, sometimes end up being too accommodating. In other words, an advisor who is unhappy with their pay may not tell the firm… but instead up and quit to go to work for another firm with better pay instead. Firms that want to retain employees will sometimes have to introduce the compensation conversation themselves.

There are also some differences in what male and female advisors are motivated by. Male advisors in our research were statistically significantly more motivated by income potential, performance pay, prestige, work-life balance, lifestyle flexibility, and interest in investments when compared to women. Males and females exhibited no differences across interest in serving or helping others, interest in personal finance, using quantitative skills, and stable pay. This could tell us that all advisors (male and female) like their jobs, but it also tells us that employees of different genders may have varied motivations for having entered into the field of financial planning.

The key point to these distinctions is that not all employees individually are motivated by the same factors. And in some cases, the personality style that makes them succeed as an advisor may actually make it harder for them to pursue their own motivators. Which makes it all the more important to open the conversation with employees about what really motivates them personally.

As a starting point, consider using our own Kitces Survey questions on advisor motivation to learn about your own advisors. Firm owners can then consider how this aligns with the firm’s own goals and then set meetings with employees and discuss how to connect the goals of the firm to the motivations of the team.

Bear in mind as well that employees’ motivations may vary depending on their personal financial situation. Those whose income isn’t high enough to satisfy their core financial needs and goals may show up as being more extrinsically motivated… at least until those needs are met, at which point they may shift to more intrinsic motivators. Fortunately, as a financial advisor, you should be a pro at soliciting this information because of all of the times you have probably had to have a similar conversation with clients about their needs versus wants in retirement… so don’t be afraid to ask questions and find out where this “line” between need and want resides for the employee!

A Few More Helpful Tips for Co-Creating 5- & 10-Year Plans

Whether you are reading this section as an advisor, employee, or an employer, you have to know your goals and be willing to communicate those goals.

For employers, likely what is important to you is a reflection of the business’ lifecycle. And no matter what the answer is, that answer is totally okay. What really matters is how you communicate the firm’s goals to your people. Ensure that the bonus structure you have in place fits the needs of the firm, while at the same time supports the intrinsic needs of the employees in order to avoid “crowding-out.”

If you are an employee, your goals matter too, and you also need to be able to effectively communicate those goals (and realize they are not going to happen overnight). Employees and employers should call meetings to discuss motivations and get to know each other. Don’t leave the meeting until you have an answer for all of the following.

- What are the firm’s goals?

- What is the employee’s life situation?

- What excites the employee about their work?

- What excites the employee about their life?

- Where does the firm want to be in 5 or 10 years?

- Where does the employee want to be in 5 or 10 years?

Once you have this information, employees and employers can work together to set up a reward system where everyone is getting what they want and need. Reward systems are great when the message behind the reward has been created mindfully and creatively. As such, we reiterate the following when it comes to designing the rewards system.

- Consider quarterly bonuses for financial reasons or for client service reasons.

- Consider bonuses for other things that both do and do not have a direct relationship with bringing in new clients.

- Consider bonuses that individually speak to an intrinsic motivation over just an extrinsic motivation, especially if the employee’s basic financial needs (and their associated extrinsic motivations) have been met.

It is simple to say, “Yes, motivation matters.” It does matter. But it matters in very nuanced ways, that may not always be so clear cut.

The biggest of these nuances being the difference between intrinsic and extrinsic motivations. Intrinsic motivators tend to be the most sustainably motivating, which for financial advisors means life-work balance, lifestyle flexibility, helping and serving clients, and a general interest in money and personal finance. Though clearly, extrinsic motivations have to be met as well (or at least, if not met, there needs to be a plan in place for how and when they will be met).

This is particularly important when we consider that the data in this study points to the fact that advisors can and do pursue large firm career tracks, grow and scale their own firms, or stay in commission-based channels, in order to climb the extrinsic motivation ladder. But employers should not just throw their hands up over this finding – you can still make a difference. For instance, taking the time to talk with employees may make them less likely to go or at least less likely to just up-and-go if they feel that their firm recognizes and supports their extrinsic motivations. The same can be true for intrinsic motivations – an advisor who is paid enough may move to a smaller firm for lifestyle flexibility and work-life balance. However, if a firm owner knows that life-work balance is key, the firm owner can implement programs and rewards to fit with this motivation.

Moreover, understanding the motivators of advisors isn’t just about advisor retention. It’s relevant for hiring in the first place as well. Recruiters, hiring managers, and firm owners need to be keenly aware of the fact that advisors are both intrinsically and extrinsically motivated, and speak to both aspects… not just the financial potential of the career as a financial advisor. Which means messages not just about money and earning potential, but also about work-life balance, lifestyle flexibility, and the relationships that advisors get to build and cultivate with clients as they serve them in the financial planning process. Financial planning is actually a career where advisors can get their cake, and eat it too!

Leave a Reply