Executive Summary

As gender dynamics in the home and workforce have continued to change (e.g., girls now outperform boys at every level of school and breadwinner mothers are increasingly becoming the norm), parents are no longer burdened with as strong of stereotypes influencing which parent (or both) should work. Which means parents have more opportunity than ever to be strategic in deciding how to structure their household, but with that increased flexibility also comes greater financial stakes – particularly for affluent households who are generally presumed to have both the most income potential as a dual-income household and the most opportunity to live off of one spouse's earnings.

In this guest post, Dr. Derek Tharp – a Kitces.com Researcher, and a recent Ph.D. graduate from the financial planning program at Kansas State University – examines why having two household incomes is not necessarily better than one, particularly given the ways in which real-world households tend to structure their expenses, and the potential to leverage the "non-linearity premium" to boost lifetime earnings for households with one earner instead of two.

Households with two incomes are generally considered to be more financially secure than households with one. However, research from Elizabeth Warren and Amelia Warren Tyagi indicates that despite the dramatic rise in total household income as families moved from a single-earner to a dual-earner structure (from the 1970s to the early-2000s), total discretionary income actually declined over that same time period. Which means total fixed expenses also rose dramatically (primarily due to the need to purchase a second vehicle and housing inflation as parents engaged in bidding wars to get their children into the best school districts), at the same time that families were losing an important financial safeguard: the ability for a non-working spouse to enter the labor force during a financial shock. Ultimately, this leads to the counterintuitive insight that dual-income households may actually be more fragile when facing a sudden loss of one spouse's income... but also an important corollary, that dual-income households can be most secure when they live off one spouse's income instead of two!

Additionally, while it would seem that dual-income households have an obvious advantage in total earning potential, this isn't necessarily the case. In some fields – particularly business, finance, and law – earnings potential exhibits what Harvard economist Claudia Goldin calls a "non-linearity premium", which means that someone who works half-time is generally going to receive less than half-time pay, whereas someone who works double the normal hours has the potential to receive more than double the compensation. In other words, a lawyer working 80 hours per week will generally outearn two lawyers each working 40 hours per week, and this is particularly true considering that a lawyer working 80 hours per week can expect to "peak" much higher in their career (e.g., making partner at a prestigious firm) than two lawyers each working 40 hours per week and sharing household responsibilities.

Ultimately, there are many financial considerations for households contemplating a dual-income versus a single-income approach... from emergency fund savings and disability insurance, to maintaining the earning capacity of a non-working spouse and considerations for divorce... and there are certainly many other non-financial considerations as well, but the reality is that it's not necessarily true that two incomes are always best. In terms of increasing financial stability and lifetime earnings potential, sometimes two incomes are not better than one!

The Financial Dynamics Of Dual-Income Households

As social and economic changes continue to redefine the division of labor within households, much has been said about the financial benefits of dual-income households. Of course, dual-income households may come with other lifestyle advantages and disadvantages as well, but the financial superiority of the two-earner approach is rarely questioned.

The math needed to reach such conclusions is fairly straightforward: So long as each spouse can earn more after-tax than it would cost hire out household tasks (e.g., nannies, cleaning services, dining out, etc.), dual-income households are assumed to come out ahead financially. Yet while this may be intuitively appealing, the financial realities of dual-income households are actually more complex, and important financial considerations can be overlooked by solely focusing on income at a single point in time.

Financial Stability With Two Incomes Instead Of One?

One of the assumed benefits of dual-income households is the stability that comes from having two incomes instead of one.

After all, one of the biggest financial disruptions a household can face is the sudden loss of all household income. Yet while there may be a risk that one spouse loses their income, the odds that both lose their income simultaneously are much lower. And thus, dual-income households are assumed to be more financially stable, as there’s generally at least one income stream to rely on.

It’s Harder To Replace Lost Income When Both Spouses Are Already Working

The counterintuitive insight that dual-income households may not actually be more financially stable is driven by the ability to replace lost income during a financial shock.

Contrary to conventional wisdom, single-earner households may actually have more ability to replace their income in the event of a higher-earning spouse’s job loss. This ability to replace household income stems from an often-overlooked economic benefit that non-income earning spouses have historically provided to household financial security: the ability of a non-income-earning spouse to enter the labor force during hard times.

Example 1. Spouse A earns $70k and Spouse B is a homemaker. However, if needed, Spouse B could realistically pick up a job at $40k. As a result, rather than a job loss resulting in the loss of 100% of household income, the net effect of Spouse A losing their job would be a 43% reduction in household income. By contrast, if both Spouse A and Spouse B both worked (bringing in a household income of $110k), then the same loss of Spouse A’s job would actually result in a 64% reduction in household income.

As the example above illustrates, if we assume both spouses do have earning potential, then the percentage reduction in household income that results from a higher-earning spouse losing their job is always going to be less when a non-working spouse can enter the labor market at the time of job loss, rather than having been in the labor market all along. Or, in other words, the percentage reduction in household income will always be less when a non-working spouse’s income can at least partially offset this loss.

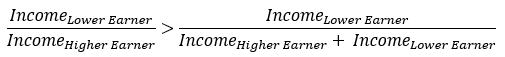

Mathematically, so long as each spouse has positive earning potential, the following is always true:

Thus, it’s simply a mathematical fact that a higher percentage of total household income can be replaced by a lower-earning spouse when that lower-earning spouse wasn’t working to begin with.

Dual-Income Couples Tend To Take On Higher Fixed Costs

Of course, the single-earner approach does have disadvantages. In particular, as is commonly acknowledged, the lack of a second income means the household has less income to put towards savings and other financial goals.

Yet, indirectly, that’s actually the point. Single-income households typically have no choice but to constrain their spending to that single earner’s income and live accordingly. Which means the non-working spouse’s ability to enter the workforce creates a safety buffer of human capital to sustain the household’s single-income spending level.

Of course, the obvious solution to the problem of a dual-income household having less potential to replace lost income is simply for the dual-income household to live like they’re a single-earner household. Yet a second key insight from Warren and Tyagi’s research is that, in practice, dual-income and single-income households structure their expenses in different ways.

In particular, a household’s fixed expenses—mortgage, auto payments, etc.—are typically driven by total household income. The more income the household has, the more it tends to actually spend on fixed expenses because it can "afford" to spend more on two incomes. For instance, a dual-income household can use both spouses’ incomes when applying for financing to purchase a home or a car, and therefore dual-income households may buy larger homes and more expensive cars. In contrast, a single-income household is forced to restrict their budget to only what they can afford based on the primary earner’s income.

In other words, while a dual-income household could live on one income and save the rest, that's rarely what such households do. Instead, dual-income households typically end up taking on higher fixed costs, which in turn makes them even more prone to financial hardship in the event of an income shock.

Example 2. Continuing the prior example, if we assume that both Spouse A ($70k) and Spouse B ($40k) are employed, the 28/36 financing rule would allow their household with $110k in income to borrow up to a monthly mortgage payment of up to $2,567. However, if only Spouse A is employed, the same household would only be eligible for a monthly mortgage payment of $1,633.

As a result, if Spouse A loses their job in the dual-income household, the $2,567 mortgage payment would consume $30,800 (77%) of the household’s remaining $40k in income. By contrast, the mortgage payment for the single-earner household would only consume a challenging-but-potentially-manageable $19,600 (49%) of the household’s annual income after Spouse B enters the labor market.

In almost any case where families lose access to a primary breadwinner, they will be under significant financial strain – perhaps enough to bankrupt families rather quickly (or at least force a move or other adjustment to reduce fixed expenses, if their emergency fund isn’t sufficient to bridge the gap until the primary breadwinner can find a new job). But, perhaps counterintuitively, the strain is substantially higher for the dual-income household, because the “virtue” of the single income household is that it tends to more effectively limit how much the household will actually spend the first place.

Why Dual-Income Couples Should Live On One Income Anyway

A dual-income household is certainly not obligated to borrow based on the maximum available through both spouses' incomes. To the extent that dual-income households can live off of the same expenses as a single-income household, they can achieve the same level of security as a single-income household, and perhaps even more, given the dual-income household’s ability to save more as long as both spouses are earning.

But again, the reality is that often households struggle to actually apply that level of constraint. For many households, budgets get stretched as lifestyle creeps higher, which means expenses add up as we find ways to justify spending more than we intended (e.g., mental accounting). That’s just what happens when we aren’t literally forced to live off of one spouse’s income. In economic terms, our Marginal Propensity to Consume additional income is almost always greater than zero.

In fact, Warren and Tyagi’s research finds that despite the dramatic increase in total household income as dual-income households became more prevalent, on average, households were becoming more financially fragile as they shifted from one earner to two.

To illustrate, Warren and Tyagi compared a single-income household in the 1970s to a dual-income household in the early 2000s. They found that while household income rose from roughly $39,000 for a typical single-income household in the early 1970s to roughly $68,000 for a typical dual-income household in the early 2000s (all numbers adjusted for inflation), discretionary expenses (assumed to cover items like clothing and utilities but not fixed expenses such as mortgage, child care, health insurance, car payments, and taxes) actually declined from about $17,800 in the early 1970s to about $17,000 in the early 2000s. Which means fixed expenses increased rather dramatically for the typical family transitioning from a one-earner to a two-earner arrangement over this time period (up 143% based on Warren and Tyagi’s estimates) while total income for the typical household rose only 76%. Warren and Tyagi point to the rise of fixed expenses as a percentage of total income as one factor that’s driving increasing financial fragility for dual-income households.

And though some may assume this means that households are spending money on frivolous things, a closer look at typical household budgets suggests that is not the case. The authors find that typical budgets are not full of luxuries and that most spending categories have only seen minor shifts (e.g., a little more on airfare and a little less on dry cleaning, but a similar net result). One notable increase is a $4,000 increase in annual auto expenses, but this is not surprising given that many families now need two cars instead of one (as a result of both commuting to two jobs, and perhaps the nature of suburban sprawl in many metropolitan areas as well).

Ultimately, the real culprit, according to their analysis, has been housing. Notably, though, this is not because families are buying lavish houses (the median home only rose from 5.7 to 6.1 rooms), but because of a premium being paid for housing as parents bid up prices in order to and get their children into the best public schools—a problem that Warren and Tyagi suggest will continue until parents are given the ability to choose which schools their children attend through a publicly-funded voucher or similar program, rather than needing to buy their way into schools based on real estate purchased in the right zip code. Additionally, the authors note the rising cost of college as a growing burden for families.

Nonetheless, the point remains: if dual-income couples want to actually be more stable than single-income households, it’s vital to manage their spending as though they were living on a single earner’s income. Even if they could “afford” to spend much more.

Non-Linearity In Earnings Potential For High-Income Individuals

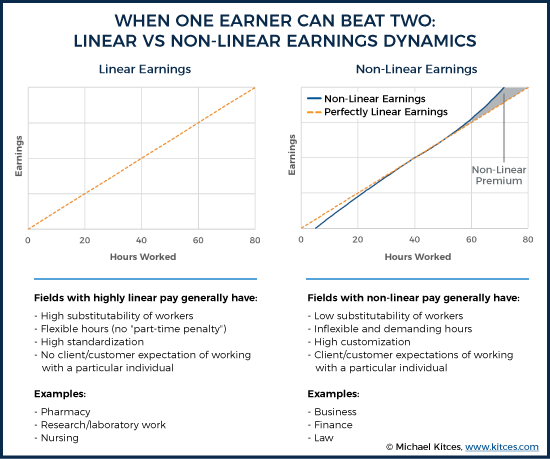

While many couples may see two incomes simply as a means to save more (especially if the lower-earning spouse’s income is higher than the costs of child care and other household expenses), the reality is that, in some careers, earnings exhibit what Harvard economist Claudia Goldin calls a “non-linearity” premium, which can actually result in less earning potential for dual-income households.

In fields that highly compensate non-linearity (such as finance, law, and corporate professions), someone who works half-time is generally going to receive less than half-time pay, whereas someone who works double the normal hours has the potential to receive more than double the compensation.

On the one hand, these dynamics coupled with the very large earnings growth seen throughout one’s career (and the tendency for those earning more to experience higher growth) can mean that even missing 5 to 10 years of experience early in one’s career can have large and lasting financial implications. Which, as Goldin notes, actually helps to explain the income gap between men and women in many careers. But it also means that, in many fields, focusing solely on one earner’s career (with the substantial overtime and reduced flexibility that will often entail) really can generate more income for the couple than each working a separate 40-hour-per-week job and then trying to share household responsibilities.

In other words, households which concentrate earning responsibility to a spouse in a field with high levels of non-linearity (e.g., business, finance, and law) may be able to actually capitalize on these non-linear dynamics. Additionally, the long-term earnings consequences of being on a higher career trajectory can further advantage a single-earner household over a dual-earner household, from a purely financial perspective.

Example 3. John and Jane are equally talented attorneys, but have decided that they are interested in having one parent stay home with their children. Of the two, John is more interested in staying home. Because law tends to be a non-linear field, Jane can work 70 hours per week and earn roughly the same as what John and Jane would earn each working 40 hours per week (or work 80 hours per week and make more than double).

Additionally, because of the limitations on the hours per week both Jane and John can realistically work while still managing their household, each would separately “peak” at earnings levels lower than what is achievable by delegating earning responsibility solely to Jane (e.g., Jane may make partner at a top-tier law firm working 80 hours per week, whereas neither would make partner at the same tier law firm working 40 hours per week) – which means that, on top of the non-linear dynamics available in the present, Jane’s career trajectory as the sole-earner may peak even higher than their joint earning potential.

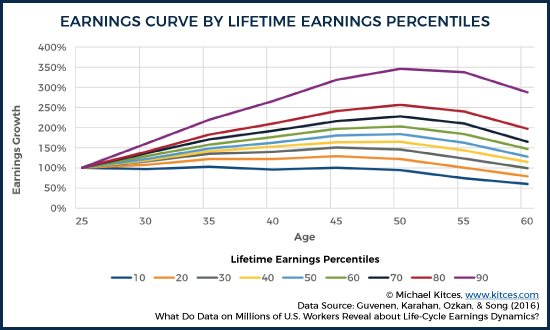

To further illustrate this point, real-world earnings curves calculated by Guvenen, Karahan, Ozkan, & Song (2016) show how higher-earning individuals experience higher levels of real income growth over the course of their career.

Example 4. Suppose that with both John and Jane working, they each expect to experience an earnings curve consistent with approximately the 80th percentile. Based on the chart above, we might expect each of their real earnings to increase about 100% from age 25 to age 50. However, due to the non-linearity of Jane’s field and their willingness to have Jane work substantial hours, suppose this boosts Jane’s earnings up to the 90th percentile. While this is almost certainly an understatement (as it is assumed here that Jane is at least doubling her prior 80th percentile earnings), even just stepping Jane up to the 90th percentile puts her on the “average” track to see nearly 200% real earnings growth by age 50 versus the 100% that each was assumed to accomplish individually. In other words, not only is it possible to more than double Jane’s earnings by working double the hours in the present, but this higher level of earnings could very likely place Jane on a path that ultimately leads to more income growth than either would achieve while needing to share other household responsibilities.

Notably, this doesn’t mean that John’s earning potential should be neglected. While he is going to miss out on career growth and advancement that would have been achieved had he been working as a lawyer, John may want to consider investing in his own continuing education and fulfilling requirements necessary to ensure he can still re-enter the labor force as an attorney later, if needed. This may even mean picking up some part-time or volunteer work, to the extent that decreases the reduction in his earning potential that is naturally going to come with time out of the labor force.

Maintaining Stability Of Single-Income Households

Given the continually evolving nature of family structures and increased focus among younger generations to find purpose in their work, households will likely continue to struggle in weighing the advantages and disadvantages of a dual- versus single-income approach. This may be particularly true for young, affluent clients, who would theoretically have the most income potential as dual-income households, but also the most opportunity to live off of one spouse’s earnings.

Additionally, as gender dynamics have continued to change (with girls now outperforming boys at every level of school and breadwinner mothers increasingly becoming the norm), parents are no longer burdened with as strong of stereotypes regarding which parent (or both) should work.

Yet with that increased freedom comes more opportunity to think strategically about whether two incomes truly are better than one in the first place… even if the couple is financially disciplined enough to manage their spending. And for couples who do choose to pursue the non-linearity and other financial benefits of focusing on just one spouse’s earnings, it’s still necessary to consider tactics to better improve the stability (and reduce the fragility) of a single-income household.

Emergency Fund Savings

One important consideration for maintaining the stability of a single-income household is the amount of an emergency fund that a household maintains.

Notably, the increased fragility of dual-income households (assuming they don’t live off just one spouse’s income, as most don’t) calls into question the common guideline that single-earner households should maintain six months’ worth of expenses in emergency fund savings, whereas dual-earner households should maintain three months’ worth of expenses.

Certainly, any individual household may need to save more or less depending on their particular circumstances, but there are a few general guidelines that can be followed. All else equal, less emergency fund savings will be needed the lower a household’s fixed expenses are relative to their total income, the easier it is for one or both spouses to re-enter the labor force or find new employment after losing a job, and the less likely it is for a spouse to lose their job unexpectedly (e.g., tenured professor versus a 100% commission salesperson).

But contrary to conventional wisdom, the ability for a non-working spouse to enter the labor force and the natural constraint that a single income imposes on fixed household expenses relative to earning capacity could actually suggest that emergency fund savings needs are higher for dual-income households.

Maintaining Human Capital For A Non-Working Spouse

When spouses have thought through the considerations and decided that a single-income approach is best, they may still want to consider making investments in the human capital of the stay-at-home spouse. As the second spouse’s “human capital” is effectively a reserve asset for them to access in the event that the primary earner loses their job, has an unexpected reduction of income, or simply cannot work any longer.

Arguably, some of the best fields for a stay-at-home spouse may be those such as health and science professions—e.g., lab research or working in pharmacy—which Goldin has identified as exhibiting no or low linearity premiums. Maintaining skills in non-location-dependent, high-demand service sector jobs may also present more financial security for households concerned about a spouse’s ability to enter the labor force quickly.

Additionally, given that workers are generally more “substitutable” in non-linear fields, scaling one’s hours up or down can be done with little to no penalty. Notably, many such fields (e.g., pharmacy) may have licensure, continuing education, and other such requirements.

Ultimately, though, when looking at a stay-at-home spouse’s earning capacity as a form of “emergency fund”, investing in keeping a spouse’s earning potential high may be more important than actually saving cash in an emergency fund (though ideally, households will have both!).

Life And Disability Insurance

Of course, concentrating earning responsibility on one spouse is a strategy which results in greater risk due to disruption of this earner’s income—making life and disability insurance even more important.

And notably, life and disability insurance become relevant for both spouses in such situations, especially when children are involved, because the disability of the primary earner can severely impair the household’s earning potential. And the disability of the stay-at-home spouse means a loss of human capital reserves for the couple, not to mention the potential need to spend more on household help (as presumably the primary earner won’t have the time/capacity to take on more household responsibilities if the couple has strategically focused on developing that spouse's earning potential in the workforce).

Unfortunately, in practice, it’s usually not feasible to obtain disability insurance for a non-working spouse. And/or to the extent that he/she is disabled, there will be no benefits payable, as there’s no way to substantiate an actual loss of income for a stay-at-home spouse.

At a minimum, though, it’s important to recognize the dynamics and risks of disability for both earners and obtain disability insurance where feasible. In addition, both spouses should have life insurance, as the death of either spouse represents a decrease in the financial stability of the household (either by losing the primary breadwinner, or the stay-at-home spouse’s human capital reserves).

Educating Children At A (Relatively) Lower Cost

As noted earlier, a key finding of Warren and Tyagi’s book is that a material portion of the increased housing costs for dual-income couples comes from their pursuit of more expensive neighborhoods they can “afford” to live in, in order to pursue better school districts.

In this context, it’s similarly notable that since the first edition of their book, there has been a rise in homeschooling rates among the affluent and well-educated. Some parents are staying home to do the education while other households are opting to hire professionals to educate children within their home, but one obvious implication of having a stay-at-home parent is the possibility to homeschool. And, if Warren and Tyagi are correct in concluding that a bidding war is going on to get students into the best schools, then homeschooling presents one way that parents can still provide a high-quality education without participating in the housing bidding war.

In other words, parents who plan on homeschooling with a stay-at-home spouse can opt for low-crime housing irrespective of the quality (and cost) of the school district, making it even more feasible to live on a single earner’s income.

Of course, Warren and Tyagi’s endorsement of a voucher system is specifically aimed at ending these dynamics, but so long as students are locked into school districts based on their address, single-earner households will have more flexibility to consider opting out of this bidding war.

Divorce And Failed Marriage

One inherently tricky consideration in the decision to be a dual- versus a single-income household are the risks associated with divorce, and this is particularly true for the stay-at-home spouse.

As noted previously, the earning potential of a working and stay-at-home spouse are going to increasingly diverge over time, particularly in careers that compound a non-linearity premium over time. This is one of the core reasons why alimony can promote an equitable split after a divorce. And, as a result, spouses contemplating the role of being a stay-at-home spouse may want to be wary of any prenuptial or postnuptial agreement which limits their ability to receive alimony.

Notably, that doesn’t mean that all prenuptial or postnuptial agreements addressing alimony are bad or unfair. Particularly in the case where there are huge disparities in income (e.g., professional athlete and a dental hygienist) the higher earning spouse may have legitimate reasons to protect their liability resulting from divorce. But stay-at-home spouses should be particularly concerned if a prenuptial or postnuptial agreement doesn’t compensate, at a minimum, for their lost earning potential due to time spent out of the labor market.

The bottom line, though, is simply to recognize that the assumption that a dual-earner approach is financially superior is not always correct. Two incomes are not necessarily the best route to maximizing household income (thanks to the potential of careers with a non-linearity premium, and higher earnings trajectories for higher-earners over time), nor even maximizing financial stability (to the extent that couples become more fragile due to not constraining their spending with higher joint income).

Instead, households which delegate earning responsibility to a single individual (particularly an individual in a field which exhibits non-linear dynamics) may experience higher lifetime earnings, and the inherent constraints that come from being forced to live off of one income instead of two can actually reduce the severity of one spouse losing their income once the ability of the other spouse to enter the labor force is properly thought of as the financial resource it is. Not to mention that households which spend less during their working years also may end up being better prepared for retirement, simply because the lower spending levels also reduce their retirement savings needs.

In the end, there are many factors beyond financial considerations that households will want to consider when evaluating whether a single-earner or a dual-earner approach is best, but households should not assume that two incomes are necessarily better than one!

So what do you think? Can dual-income households be more financially fragile than single income households? Does the non-linearity premium suggest that a single-earner approach can be the wealth-maximizing strategy for a household? What other financial considerations are relevant when contemplating a single-income versus dual-income approach? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!