Executive Summary

For many financial advisors, one of the most frustrating bottlenecks in the planning process is the data-gathering phase, where client procrastination frequently stalls progress before it even begins. Onboarding requires effort from clients themselves: locating documents, completing forms, and granting account access. This work is often tedious, emotionally charged, and unglamorous, which can cause even highly motivated clients to get stuck. However, these delays don't necessarily reflect a lack of interest or commitment; clients can deeply value financial planning and still struggle to act on it.

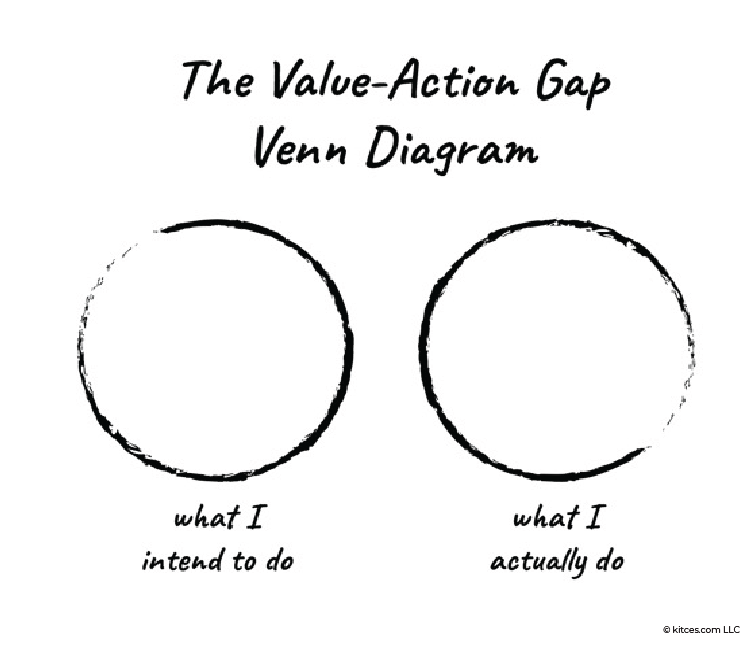

The core challenge stems from what behavioral psychologists call the "value-action gap": the disconnect between what people say they want and what they actually do. Clients often defer onboarding tasks not because they doubt the advisor's value, but because the tasks feel overwhelming or uncomfortable. This behavior isn't unique to financial planning; people procrastinate things they care about all the time, from exercise to decluttering. At the heart of this struggle is a concept called "momentary distress tolerance" – the ability to endure short-term discomfort in service of a longer-term goal. While some advisors aim to work around this with synchronous "Get Organized" meetings or similar solutions, it's difficult to eliminate client 'homework' entirely. And when motivation falters, discomfort often wins out, leading to stagnation.

Traditional motivation strategies – like emphasizing the benefits of completing onboarding – often fall flat because clients are already convinced of financial planning's value. In many cases, the barrier is more often an issue of bandwidth, not desire. Gabriele Oettingen's WOOP framework (Wish, Outcome, Obstacle, Plan) offers a practical, research-backed strategy to bridge the gap between intention and action. WOOP encourages clients to articulate not only their goals but also the internal and external obstacles likely to impede them – and to create if/then plans for overcoming those obstacles. For example: "If I get bored looking for paperwork, then I'll set a 20-minute timer to stay focused."

The real power of WOOP lies in its simplicity and adaptability: it doesn't require worksheets or a rigid script – just a natural conversation about the client's goal, why they want it, what might stand in their way, and how to get around it. Advisors can guide clients through this mental exercise informally in meetings, particularly when assigning tedious or low-reward tasks like gathering account statements or completing estate planning documents. By helping clients visualize potential friction points and prepare responses in advance, advisors make it more likely that clients will follow through and avoid the limbo of incomplete onboarding. Over time, this practice builds more client self-awareness while reinforcing the advisor's role as a thinking partner – not just a taskmaster.

Ultimately, when clients are supported in identifying their own motivational roadblocks and equipped with strategies to overcome them, they're more likely to stay engaged, follow through, and experience the true benefits of financial planning. This allows advisors to spend less time chasing paperwork and more time delivering meaningful, high-impact advice to their new clients!

A fundamental value proposition of financial planning is that the client can delegate the mental load of managing their money – whether its keeping track of their accounts, making investment allocation decisions, or managing portfolio withdrawals – so their lives feel easier. This peace of mind is often a cornerstone of the value a financial advisor provides.

At the same time, delegation requires the client to do a lot of work: digging up otherwise-abandoned 401(k) plan statements, filling out financial forms, signing contracts, and ensuring that their investable assets are in the right places and that the advisor has access to them. While advisors may want to help, much of the work still needs to be done by the client. And data-gathering isn't especially fun. Dredging up old documents is often tedious (even if the client is excited to begin their financial planning journey!) and may bring up feelings of shame or anxiety about disorganization, past financial mistakes, overspending and under-saving, or investment decisions they meant to 'fix' but never did – especially when having to share this all with someone that the client doesn't even know that well.

In an ideal world, the advisor helps clients understand exactly what they need to gather, the client powers through the to-do list (even if they have to grit their teeth a little while doing so), and the relationship quickly moves forward, allowing the advisor to dive into solving problems and demonstrating their value.

In reality, this data-gathering phase often hits delays and roadblocks. Advisors may need specific information or access to certain accounts, while clients procrastinate or delay the process for one reason or another.

It's Not That Clients Don't Value Financial Planning…

Client procrastination in data-gathering is not uncommon. Sometimes, it might be tempting to assume that procrastinators don't take the relationship (or the advisor's time) seriously or buy into the value of financial advice; however, this isn't necessarily true. People procrastinate things they value all the time, from exercise to housework to applying for jobs. They may want the rewards (greater health, a cleaner living space, a healthier work/life balance) and even know exactly what it takes to get there. But while many enjoy having a clean house, few enjoy the process of cleaning itself (though there are some exceptions).

Financial planning words the same way. Clients likely hired the advisor, in some part, because working through the details needed to build a robust financial plan isn't satisfying to them. They still value the end result and the relationship, but not the tasks it takes to get there.

There are a myriad of terms for this phenomenon; it's most commonly called the value-action gap, belief-behavior gap, or the KAP-gap (KAP standing for Knowledge-Attitudes-Practice). But, whatever it's called, the distance between intention and action is strikingly clear. As Shakespeare might remind us, a procrastination behavior called by any name would smell just as sweet.

As Oliver Schnusenberg summarized in his Financial Planning Magazine article, "Navigating Client Engagement: Considering Client Knowledge and Willingness":

Unfortunately, clients often do not implement planner recommendations (Klontz, Horwitz, and Klontz 2015). The best recommendation is useless if it is not utilized by the client (Somers 2018)…

The willingness of the client to implement a planner's recommendation can be considered in the context of the distress caused by implementation.

In this case, "distress" is broadly defined as stress and anxiety – very understandable feelings to come out of sorting through and preparing one's financial history and accounts for them to be scrutinized by a near-stranger.

The ability to 'power through' these feelings of discomfort is called momentary distress tolerance, a term coined by psychologist Jennifer Veilleux (and discussed in Schnusenberg article). While some people may have a higher distress tolerance than others, it's most accurate to assume that everyone is great at momentary distress tolerance, even though we may not be equally great at momentary distress tolerance across all areas of our lives.

A useful example of this is exercise, an activity that people often avoid due to momentary distress tolerance (and other obstacles). If a group of people have figured out how to exercise consistently, each of them has probably landed on a different solution: one person may run while their friend bikes; someone may join a fitness class while another lifts weights by themselves. Ultimately, people will gravitate to what they find most tolerable and that minimizes the distress associated with the activity. This life design principle applies in many areas of life – people switch career fields to find more fulfilling work and outsource work they don't enjoy (including financial management work to their financial advisor!).

Ironically, though, the client's effort to delegate financial planning begins with detail-heavy data-gathering. Little wonder, then, that so many struggle to complete this first step of financial planning engagement on time.

Motivation

Advisors are often well aware of the data-gathering struggle and want to make this process less painful for new clients. Some advisors offer a "Get Organized" meeting – working alongside clients to gather and sort financial information in real time. This builds momentum and reduces the amount of work that a client must complete on their own terms (and with their own level of motivation).

Technology can also help. Many financial planning solutions have added gamification elements to their software design, adding small rewards for clients as they make progress. This might be something as simple as displaying a percentage-completed bar filling up as a client makes progress, but it can tap into dopamine release and be a powerful way to make the work feel more engaging.

However, while these strategies may make the process easier, they don't eliminate the reality that it's impossible to completely avoid client 'homework'. In these instances, momentary distress tolerance comes into play. Clients usually respond in one of two ways: either they use self-control to push through to completion, or avoidance wins and the work goes unfinished.

This is frustrating for both the advisor and the client. It often feels as though clients (and everyone else) ought to be able to simply push through, yet, in practice, this happens less often than most would like to admit. Negative feelings such as shame, confusion, overwhelm, or even boredom can derail progress and halt momentum in its tracks. However, the work must still be done. What are the advisor and client to do?

When Motivation Isn't Enough

Motivation advice often emphasizes focusing on the end result. And while it's important for clients to want the outcome, simply wanting the end result doesn't get them through the often difficult and unglamorous steps to get there.

In her book Grit, psychologist Angela Duckworth notes that people have a limited amount of grit to 'spend'. And grit matters here because clients need it to push through the tedious, often unpleasant steps of financial planning – like digging up old accounts or organizing paperwork. While some people naturally have more grit than others, many find their supply split across "competing goal hierarchies" – different sets of goals that don't all point toward the same top-level aim.

In her book Grit, psychologist Angela Duckworth notes that people have a limited amount of grit to 'spend'. And grit matters here because clients need it to push through the tedious, often unpleasant steps of financial planning – like digging up old accounts or organizing paperwork. While some people naturally have more grit than others, many find their supply split across "competing goal hierarchies" – different sets of goals that don't all point toward the same top-level aim.

For example, a client may have the top-level goal of engaging a financial advisor, but that competes with other top-level goals, like advancing in their career or caring for family. Each of those goals comes with its own cascade of mid-level and low-level tasks. The result is that, by the time clients sit down to act on financial planning, their grit reserves may already be drained.

Even the act of engaging an advisor creates its own mini-hierarchy: assessing the advisor for a personality/philosophical fit and suitable fee schedule, filling out screening forms, scheduling an initial call, and – if they decide to move forward – tracking down and organizing their financial data, signing the necessary paperwork, and completing the data-gathering step to move forward. And life doesn't stop because they're hiring a financial advisor. When these steps compete with the rest of life's demands, there's a good chance that they'll have very little grit to spend and that distress tolerance – and ability to push through the emotional discomfort and ennui – is greatly reduced. Which means clients are more likely to stall, creating that frustrating place of data-gathering limbo .

In short, even when clients want the end result, that vision alone may not be an effective motivator for action. Psychologist Gabriele Oettingen calls this "positive fantasizing", and her research suggests that it can actually be less motivating to think only of the positive end result. In one of her studies, participants asked to describe their ideal week showed lower energy levels and were less likely to act on those goals than participants who discussed a 'neutral' week.

As the study puts it:

These findings suggest that as positive fantasies allow people to mentally experience a desired future in the here and now, such fantasies may deter people from mobilizing the energy that is needed to bring about their desired future…. Needs energize people, and need satisfaction decreases energy expenditure.

Having the end in mind didn't strengthen tenacity – it weakend it!

Start With Obstacles

If starting with the end in mind is counterproductive to ensuring action, then what does work? In Oettingen's study mentioned earlier, participants who described 'neutral' weeks – especially noting the obstacles they expected to meet along the way – ended up having more productive weeks. Anticipating obstacles had an energizing effect and made the subjects more likely to be proactive and follow through.

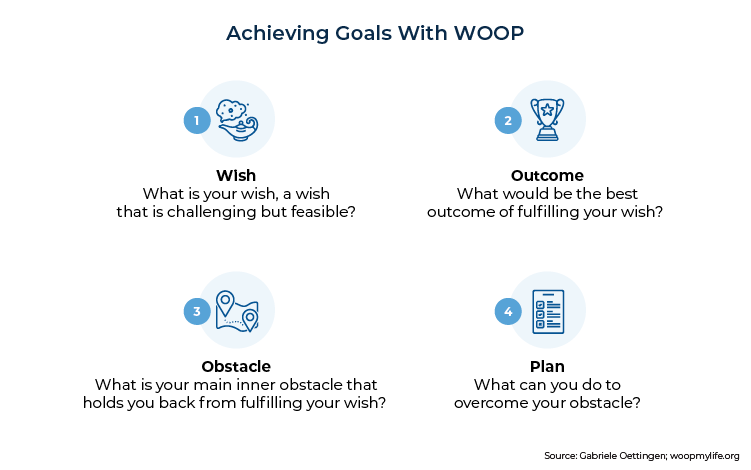

In social psychology, this practice is referred to as "Mental Contrasting with Implementation Intentions" (MCII). Perhaps the most user-friendly framework for applying MCII is Gabriele Oettingen's Wish – Outcome – Obstacle – Plan (WOOP) model. In her guide to practicing WOOP, she explains the questions tied to each step:

- Wish: What is your wish, a wish that is challenging, but feasible?

- Outcome: What would be the best outcome of fulfilling your wish?

- Obstacle: What is your main inner obstacle that holds you back from fulfilling your wish?

- Plan: What can you do to overcome your obstacle?

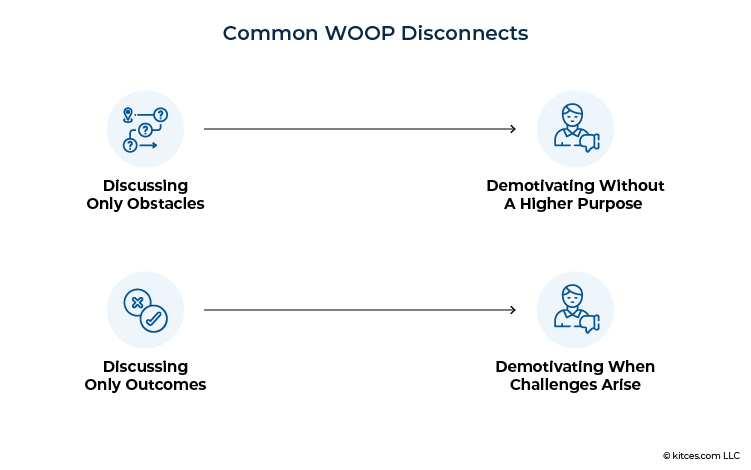

Read from top to bottom, WOOP starts with the Wish and Outcome steps, then moves into the more granular process of achieving those goals in the Obstacle and Plan steps. Both halves are essential and involve envisioning a concrete result and the potential obstacles – one is not as effective without the other.

Focusing solely on potential obstacles is deflating and can hinder momentum, while focusing only on outcomes can leave clients unprepared to handle the challenges that inevitably arise.

For WOOP to work, a few components need to be in place. First, the client must be wholly bought into the Wish and Outcome. The Wish often reflects the concrete end goal (e.g., "Complete onboarding with my financial advisor"), while the Outcome captures the intrinsic reward, which can be a feeling or a longer-term result ("Peace of mind and a solid retirement plan").

When naming Obstacles, Oettingen's research – and MCII principles – often focuses on intrinsic barriers such as boredom or busyness. These are certainly powerful levers, but in advisor-client conversations, it can be just as valuable to address both intrinsic and extrinsic obstacles that can slow progress.

Finally, the Plan works best when framed an if/then statement, where the 'if' identifies the obstacle and the 'then' lays out the client's solution:

- If my attention starts to drift… Then I'll set a timer for 20 minutes and see what I can get done.

- If I'm having a hard time blocking out time to find all of my information… Then I'll order takeout to free up an evening for paperwork.

Discussing both the obstacles and plans pushes clients to turn their focus from the 'big picture' of success to rehearsing the granular steps it requires to get there. .

In a data-gathering framework, a WOOP exercise may look like this:

- Wish: Complete the client onboarding tasks and officially 'start' as a financial planning client.

- Outcome: Peace of mind; a clear retirement plan.

- Obstacle: Time management to find everything; boredom.

- Plan: If I feel myself getting bored, then I'll set a timer to keep working for 20 more minutes before allowing myself a break. If I do that a few times, I should be able to work through almost everything.

Using WOOP In A Client Meeting

Utilizing WOOP in a client conversation doesn't need to be formal. While Oettingen and others provide worksheets and handouts that can be used as meeting aids, it may feel more natural to simply lead a client through the steps conversationally.

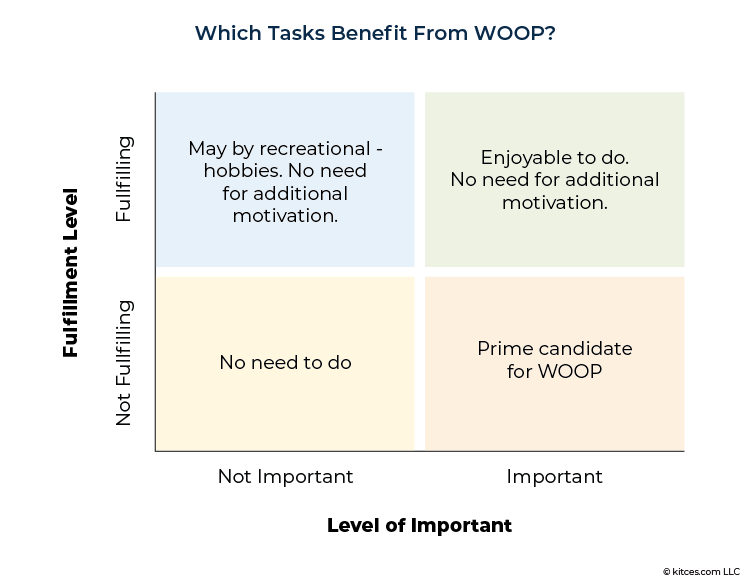

Many financial planning 'homework assignments' are good fits for a WOOP approach – simply because tasks like logging into financial accounts or tracking down old documents are not intrinsically exciting. Tasks that are naturally fulfilling are usually just a matter of finding time to do them. But tasks that are less fulfilling but still important often need more structure and strategy to ensure they actually get done.

Advisors can use their discretion for when WOOP is most useful. If the assignment is one where many clients stall (e.g., estate planning) or if a particular client consistently struggles with deadlines, starting with WOOP can help. Likewise, if a client has been procrastinating despite agreeing that the work is important, WOOP provides a chance to dig more deeply into the (potential and realized) blocking points.

When using the WOOP framework, it's usually helpful to move from the top down. That said, it's not necessary to ask all of the questions. Instead, pick one or two per category or adjust the phrasing to discover what feels most natural. The following sections explore each WOOP step with ideas for how advisors can bring each one into a client conversation.

Step 1: Start With The Small-Picture Wish

Early in the relationship, beginning with Wish and Outcome can reaffirm mutual excitement about getting started. In the WOOP framework, Wish is about understanding the immediate objective. For advisors, this is the moment to ensure that the client understands what's required to move forward (e.g., that the financial planning 'relationship' can't truly begin without this information).

Using the Wish step to ensure the client understands the outcome and why it matters is crucial. Emphasizing how the Wish applies to their Outcome (such as truly accurate retirement planning) as the discussion progresses can help reinforce motivation.

Wish Discussion Starters:

- Do you understand how [X] and [Y] tie together?

- Let's talk about how [X] impacts [pain point].

- Once we have [X], then we can begin on [pain point].

- Do you feel clear on what needs to be done, and what the result will be?

Step 2: Discuss The Long-Term Outcome

Outcome focuses on the bigger-picture results. This is an opportunity to reiterate both the advisor's excitement and to remind the client of why they engaged in the first place.

Revisiting Wish (and Outcome) can also be very powerful tools when procrastination sets in, especially for ongoing assignments. For example, if the client stalls on onboarding tasks, it may help to sit down and ask if they truly want to begin. If there is a misalignment between the stated Outcome and what they really want, then their odds of completing a task are low.

Outcome Discussion Starters:

- I'm really excited to get going to so that we can finally start on [pain point].

- What are you most looking forward to once we've worked through [X]?

- Once you've gotten everything uploaded, what are you most excited to start on?

Step 3: Identify Potential Obstacles

WOOP emphasizes naming intrinsic blockers, but advisors can also use the discussion of Obstacles to answer lingering questions on how to do various tasks and discuss common blocking points clients encounter.

Ideally, clients will name their own pain points, and advisors can mirror that language back to them. For example, if the client says the work is boring or complicated, then use those same adjectives. If clients hesitate – especially in the early days of the relationship – it can help to normalize the struggle (e.g., "Many of my clients struggle with the same issue of [X]") o share examples of common blocking points (e.g., "I know that this work isn't necessarily fun") to see what resonates or encourages the client to share more.

Obstacle Discussion Starters:

- What do you think the hardest part of completing this will be?

- What would get in your way, if anything, of completing this before [X]?

- Looking over this checklist/to-do list, what's your first reaction?

- What questions do you still have for me about the checklist?

Step 4: Develop – And Agree On – A Plan

If the client opens up about their blocking points, the advisor can then work with them to develop a strategy during the Plan stage of the WOOP framework. Extrinsic blocking points identified in the Obstacle discussion – such as uncertainty of where to find old accounts – can often be resolved with checklists or pointers. Intrinsic blocking points are where the if/then framework really shines.

Much as how clients benefit most from naming their own obstacles, it's also ideal if they propose their own solutions, though the advisor can offer suggestions as a sounding board.

Empathy – and even some light-hearted humor, if appropriate – can go a long way. It's okay to acknowledge that these steps are complex or boring! Something as simple, "Yeah, I hear you. This stuff can be really [X]" can validate the client's vulnerability and effort. Plan Discussion Starters:

- What have you tried in the past whenever [X] has come up?

- If [X] happens, then how do you think you'll move past it?

- Let's come up with a game plan on how to work through [X]. Any ideas?

To close the conversation, advisors can review the checklist one more time, acknowledge the Obstacles, and briefly reiterate the Plan before closing with a reminder of the ultimate Outcome. This reinforces progress and helps the client leave the meeting wit ha clear sense of direction.

Ultimately, the key point is that the WOOP framework can be a powerful way to help clients name their own blocking points – and identify solutions to work past them! When clients buy into the short-term Wish and long-term Outcome, while also anticipating Obstacles and creating a Plan , they're more likely to complete their assignments promptly. And that means advisors can spend less time waiting on paperwork and more time doing the high-value work clients hired them for!