Executive Summary

As financial advisory firms grow and accumulate more and more clients over time, the increased client load creates a growing pressure to find ways to be more efficient to scale the business. Yet the challenge is that with an ever-growing client base, where each different client has different needs – and where advisory firms often differentiate themselves by providing individualized and customized services to the differing needs of every client – it becomes increasingly difficult to systematize the business, precisely because the level of variability from one client to the next makes it difficult or impossible to scale efficiently.

Rather than trying to figure out how to gain efficiency when serving an ever-widening range of clientele, though, an alternative approach is to actually try to tackle the issue of “client variability” itself, recognizing that having clients with a wide range of needs is itself a choice of the advisory firm… as is the firm’s decision of whether or how much to accommodate those varying needs (and/or whether or how to charge more for the service of greater individual customization).

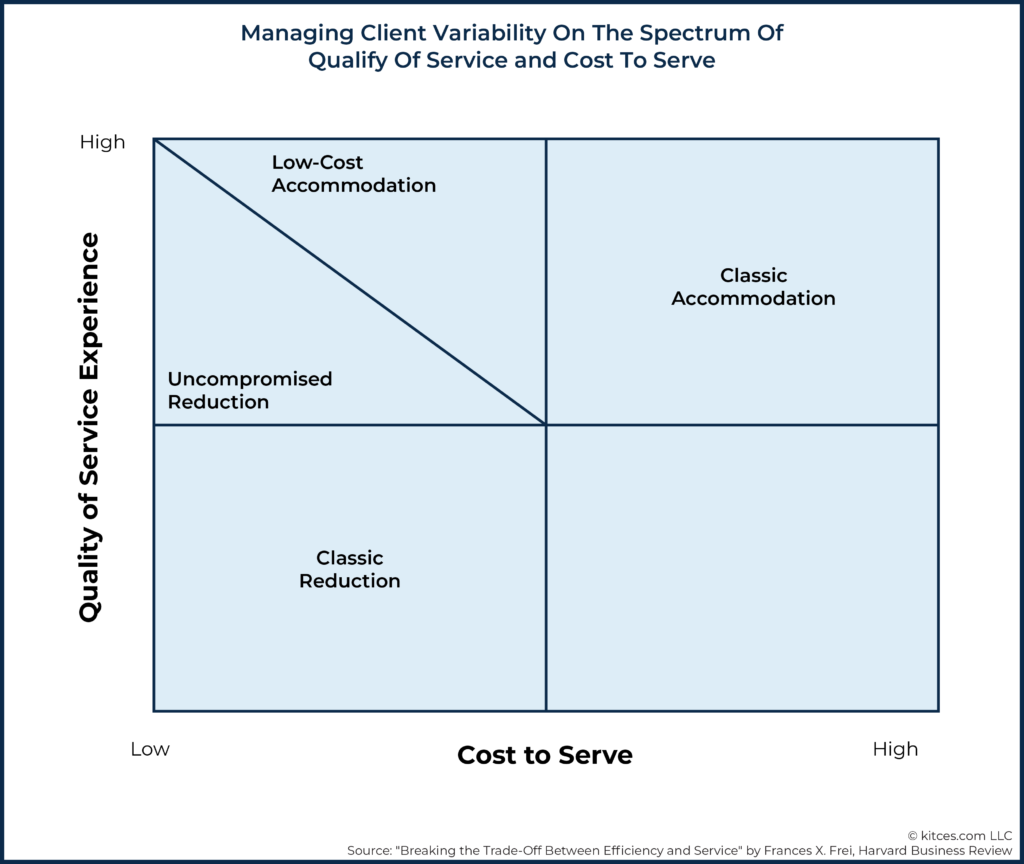

In her Harvard research on “Breaking the Trade-Off Between Efficiency and Service”, Dr. Frances Frei highlights two alternative strategies to manage client variability between just “doing more and charging more” or “doing less and charging less”: low-cost accommodation where the firm offers flexibility to clients but ‘only' within a fixed range of choices, and uncompromised reduction where the firm doesn’t make compromises in the services it offers but instead reduces the breadth of who the firm serves in order to have a more focused clientele where their ‘customized’ services can still be delivered as repeatable expertise.

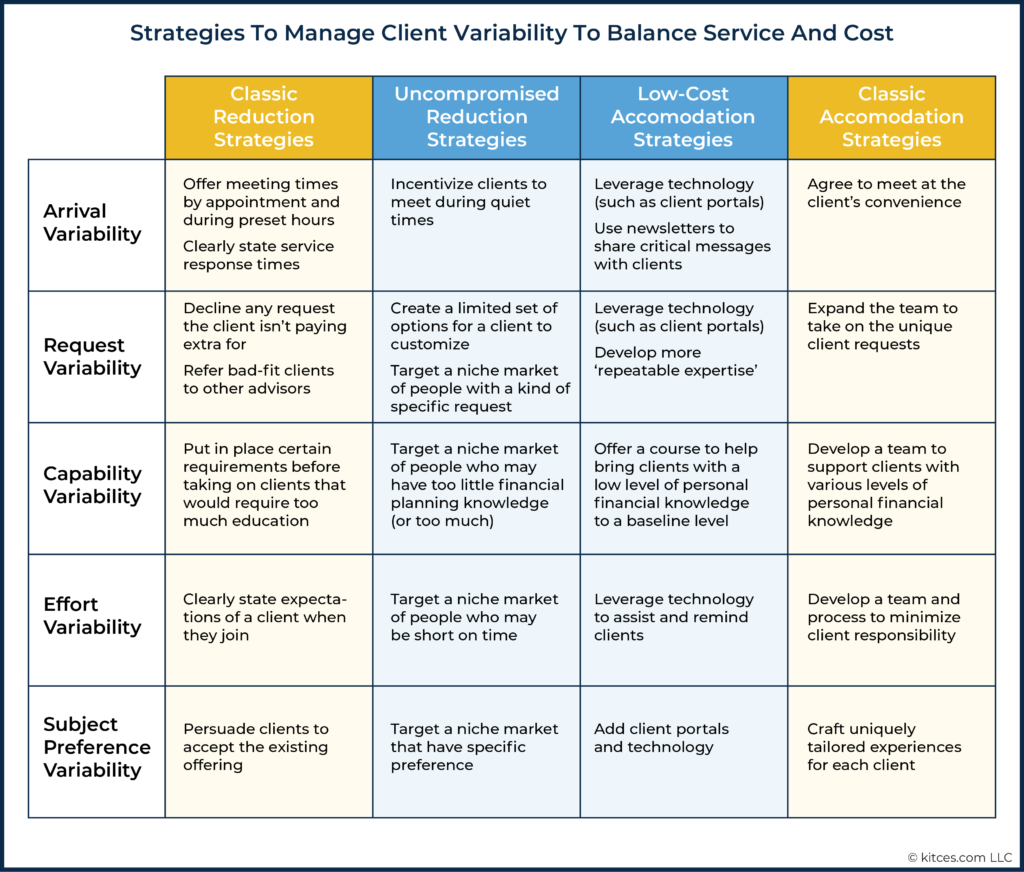

These techniques to manage client variability can then be applied across each of the domains where client variability occurs: manage ‘arrival variability’ (when clients meet) by offering them incentives to meet during quiet times of the year and/or using flowcharts, checklists, or other client educational materials to handle common client questions without a meeting; manage ‘request variability’ by rolling out a portal for clients to access their own reports/requests on demand, or by purchasing more specialized tools and then systematically rolling out analyses or solutions for all clients who might be interested in a similar service; manage ‘effort variability’ by implementing tools like Knudge or and e-signature to make it easier for clients to get through the process, or consider rolling out a service to turn a challenge into an opportunity (e.g., converting the data gathering meeting into a “Get Organized” meeting); and manage ‘subjective preference’ variability by either creating a standardized solution for more common client preferences (e.g., a set of ESG models for SRI-oriented clients), or by systematizing their higher-level service requests (e.g., creating a standard [email protected] that top clients get to have their needs handled quickly by anyone on the team who gets/sees the request first).

Ultimately, though, the key point is simply to recognize that the challenge of having an ever-widening range of clients with an ever-widening range of demands – and the challenges of efficiently scaling across such a wide range of needs – is itself a choice that an advisory firm has. Which means it’s not only a matter of either doing-more-and-charging-more or doing-less-and-charging-less, as there’s also an opportunity to either find more scalable low-cost accommodations to make that also enhance efficiency, or to choose a less-variable range of clientele in the first place in order to create room to provide a deeper service for those clients’ unique needs.

Client Variability: Different Clients All Have Different Needs

When an advisory firm first launches, the reality is that most firms are simply trying to attract any clients and revenue that they can. And when there is a lot of time and not a lot of clients, firms will often make any number of ‘small’ accommodations to win the client, keep the client, or because the client has a unique planning need.

For instance, perhaps one client is an engineer and wants to see detailed cashflow analysis at their meeting, but all other clients see a high-level goals-based planning analysis. Another client might want the advisory firm to help them with the tax analysis on how to diversify out of an existing concentrated stock position, but all other clients come to the firm with 401(k)-to-IRA rollovers where there are no embedded-gains issues. A third client may be a small business owner in a rapidly growing but dynamic business who insists on in-depth quarterly meetings, when all other clients are quite content with the firm’s twice-per-year meeting cadence.

Notably, this phenomenon is not unique to financial services. All service-based businesses struggle with the balance between serving clients consistently and accommodating each client’s own unique needs. Frances Frei, who wrote “Breaking the Trade-Off Between Efficiency and Service”, studied this dilemma, and identified five general variables across which customers or clients may ask for something different:

Arrival variability occurs when a client wants to meet at times that are outside the advisor’s typical arrival (i.e., meeting) structure. As in practice, most advisors have a natural meeting cadence that develops with their clientele, whether it’s a once-per-year annual review, meeting semi-annually with their clients in the spring for tax planning and then again at the end of the year, or a quarterly check-in for the firm’s top clients. There are also timeframes where the advisor typically holds meetings: for instance, meetings are only at the advisor’s main place of business during normal business hours, but the advisor will also meet with clients in the evenings on Tuesdays and Thursdays, or do virtual Zoom check-ins on Friday mornings for those who are busy during the week. But when clients don’t want to or are not willing to meet with their advisor during ‘normal’ business hours, and instead insist on an accommodation, arrival variability is the end result.

Request variability occurs when clients make unique requests or have unique planning needs. For instance, the financial advisor may have a typical series of pages that they output from their financial planning software, but one client wants to see a specific kind of analysis during the meeting that is not part of the standard report. Or the financial advisor may typically work with retirees to help them plan through managing their retirement portfolio and generating retirement income, but takes on a new client who owns a rapidly growing small business, does not fit the typical mold of the advisor’s existing clientele, and wants additional tax and small business planning outside of what’s typically provided to the firm’s ‘normal’ clientele.

Capability variability emerges when clients have varying levels of financial acumen they bring to the table in meeting with the financial advisor. For instance, some clients may be very familiar with personal finance and able to converse with the advisor about complex planning issues, while other clients may be completely unaware of their own financial situation and need substantial financial education just to have the conversation. The end result is that everything from the talking points, to the marketing, to the reports and discussion itself, all may have to be modified based on the client’s capability to understand.

Effort variability occurs when different clients show varying levels of willingness to exert their own effort to help the advisor do their job. For instance, while some clients may quickly find and gather the necessary information for the advisor to do their financial planning analyses, other clients may drag their feet and take a long time to get the information or just be unwilling to exert the effort to do it all, resulting in a potentially drastic range of time from one client to the next in how long it takes to get through the financial planning process.

Subjective preference variability is the simple phenomenon of each client having their own personal preferences (beyond arrival, request, capability, and effort variability). For instance, when an advisor upgrades their conference room to create a ‘high-end’ experience with elegant furniture and dark wood paneling, some clients may be impressed, but other clients may see it as a negative reflection of where their advisory fee is going… leading the firm to then establish a second conference room for their more ‘modest’ clientele as well. Similarly, an advisory firm may find that some clients prefer to have meeting confirmations occur by email, while others want a confirming phone call, and still others would rather receive a simple text message instead. With subjective preferences, there is no one “right” answer about what to do, only choices that may appeal to some clients’ preferences (and be a potential turn-off for others).

Notably, advisory firms serving a wide range of clientele may face multiple different types of variability at once, as different clients that have been added over the years each have their own requests, their own needs, and their own preferences.

How Client Variability Limits Business Efficiency And Scalability

The recognition that each client may have their own unique needs and circumstances is, to some extent, simply endemic in financial planning itself, which is all about understanding a client’s own unique goals and helping them map a path to achieve them.

Yet, the significance of client variability is that it goes beyond ‘just’ understanding a client’s needs and objectives in order to craft advice recommendations to implement. Client variability is about all the ways that advisory firms may need to accommodate their “normal” business practices for the unique needs of any particular client.

These accommodations all have business ramifications beyond just the work itself that’s done for the clients who request them. As some reminder needs to be put in place for the advisor (or someone on the advisor’s team) to double-check that the unique report is prepared, or that the additional analysis is conducted, or that the extra meeting is scheduled, for that single client.

On the surface, such small and ‘easy’ accommodations that advisors commonly make are good business sense to keep their clients happy. But when multiple accommodations are made to different clients, each with their own particular needs and requests, problems begin to emerge. As when enough accommodations are made, no two clients have the same needs, receive the same experience, or can be served by the same process. Which means the advisory firm begins to lose its ability to efficiently scale the business as it grows.

In other words, growing advisory firms often struggle with efficiency and scalability not because it’s impossible to scale an advisory firm in an efficient manner… instead, it’s these small accommodations made for the clients over the years that lead to an advisory firm being inefficient. It’s not one single decision that results in an inefficient advisory firm, it’s the cumulative result of hundreds of small accommodations that result in a breadth of client needs that can’t be served efficiently.

Alternatively, some advisory firms that previously had a more focused clientele (with less client variability) can unwittingly find themselves growing in a direction that introduces more client variability.

For instance, Jennifer is a financial advisor who works mostly with retirees. These clients were primarily small business owners who originally met Jennifer at local Chamber of Commerce meetings, and have since sold their businesses and retired. As a result, Jennifer’s clientele are all of a similar age and dealing with similar issues, mostly focused on distribution strategies and tax management of their retirement portfolios. And because Jennifer’s clients are all retired and now have flexible days, they all prefer to have their meetings mid-day between 10am and 3pm (to avoid rush hour), which works well for Jennifer to have a nice work-life balance.

However, because Jennifer has done such a good job working with her retired clients, they have begun to introduce her to some of their adult children who need advice and guidance. These adult children don’t have much in common with each other, though, nor even with their parents. Some are in different states and have insisted that Jennifer meet with them virtually and not in person. Some are successful business owners, while others need help with basic budgeting and cashflow management (which Jennifer’s current financial planning software doesn’t handle well). And due to time zone differences and client work schedules, Jennifer is increasingly being asked to meet in the evenings outside normal business hours.

In other words, Jennifer’s expansion to a new segment of clients is resulting in a series of new client variables being introduced. The younger clients want to meet at a different time of day, which is the arrival variable. Some clients have unique budgeting planning needs (which is a request variable). And still some others, just need extra hand-holding to understand what all of the statements and reports mean (capability variable).

The end result is that what was once a relatively well-organized advisory business has quickly become inefficient based on the clients Jennifer took on!

The key point, though, is simply to recognize that client variability itself is a factor that can inhibit the efficiency and scalability of an advisory firm. As when a firm’s clientele are all of a consistent type with a consistent need, it becomes easier to serve them efficiently. But when a firm has a wide range of clientele with significant variability – or even ‘just’ grows in a new direction that introduces new types of clients with new variability demands – it quickly becomes difficult to serve those clients efficiently, because of their variability!

Strategies to Manage Client Variability As A Path To Advisor Efficiency

To some extent, dealing with variability in clients comes with the territory of offering a service, and all service-based businesses must deal with it. Nonetheless, it’s still important to consider putting guardrails in place to make sure that client variability is managed.

In other words, there is a common belief that making accommodations for client variability is a simple “yes” or “no”. Either the advisor will run that special report, or meet after typical working hours with a client, or they won’t. In reality, though, there are more nuanced ways of dealing with client variability, which Frances Frei has explored:

- Classic Accommodation: When an advisor simply agrees to a client’s request, it’s classified as a “classic accommodation”. In many service-based businesses (advisory firms included), there is an expectation on the part of the client that most services can be flexible to accommodate their requests. In fact, this is one reason why advisors can justify their fees… because they can provide very customized services for their clients. The downside, though, is that it often requires more staff and advisors to deliver on the promise, which means the business isn’t necessarily more profitable due to the higher costs (and may be even less profitable due to the resulting inefficiencies of innumerable ‘small’ accommodations that add up!).

- Classic Reduction: When an advisor is unwilling or unable to accommodate a client’s request, and either declines or only accommodates it within specified limits, it’s considered a “classic reduction”. There is some concern (and rightfully so) that being inflexible to a client’s unique needs will result in a negative impression, but doing so often brings great efficiencies (with a very standardized offering) that makes it easier to reduce costs and compete on price. In fact, price-conscious clients may prefer to work with an advisor in this capacity, if it means the price is right. They value a cheaper price over an accommodative service (akin to choosing the lower-cost bulk retailer, discount airline, or movie matinee) while giving up the opportunity to charge more to those who might reject a “cookie-cutter” and would prefer a more customized experience.

- Low-Cost Accommodation: A mid-point approach between saying “yes” to every variable client request, or only forcing clients into a limited number of fixed choices, is to agree to make accommodations but only if the request can be automated, done by an assistant, or developed as a self-service option (e.g., on-demand ATMs in the banking industry, or perhaps on-demand performance reports by granting clients direct access to a performance reporting portal) where the client can satisfy their own need, on their own terms, which they may obtain as a part of the relationship with the advisory firm but without needing to rely on the advisor to do it for them.

- Uncompromised Reduction: Instead of accommodating a client’s request to the point of inefficiency, this approach embraces certain client requests to the point where the advisor tries to attract other clients who want the same accommodations… reducing variability not by forcing the client to make compromises, but by reducing the range of clients to the point that the ‘uncompromised’ accommodation becomes a standard (at least for that segment of clientele). In the advisor context, this is the transition an advisory firm goes through in either standardizing its client segmentation (e.g., taking the accommodations most often requested by an “A” client and rolling it out as an efficient service offering for all “A” clients), or pivoting the advisory firm into a particular niche clientele (e.g., one of the six categories of niches, including Affinity, Values, Educational, Experiential, Psychosocial, Technical, where the commonalities of the niche clientele mean they often want the same accommodations).

The chart below illustrates how the general strategies relate to each other. While Classic Reduction and Classic Accommodation exist on the traditional spectrum of lower service for lower cost versus higher service with higher cost, it’s actually the Low-Cost Accommodation and Uncompromised Reduction strategies that can provide a more compelling compromise both in terms of quality and cost.

Sample Approaches To Managing Client Variability

When it comes to dealing with client variability, there isn’t necessarily a single “right” or “wrong” solution. But it is important to recognize that the “classic accommodation” approach of simply acquiescing to any and every client request in the name of “good service” is inherently limiting in the firm’s ability to be efficient and scale. Which at a minimum, means the firm should anticipate needing to charge an above-average fee to accommodate for its above-average accommodation strategy.

For those who don’t want to compete with the most expensive service (to accommodate their client accommodations), the alternative is to implement one of the other approaches to manage client requests, across any of the various domains of client variability.

Managing Arrival Variability - When Clients Want To Work With You

When it comes to arrival variability – those situations where clients want accommodations when it comes to meeting times and arrangements – the classic accommodation approach is to embrace the variability of the client by agreeing to meet just about any time and anywhere that is most convenient for the client. Though as noted earlier, this may eventually incur additional costs, such as having extra advisors to be able to meet with clients in case one advisor is already booked with a client meeting or is on vacation.

Alternative strategies include:

Classic Reduction:

- Offer meeting times by pre-scheduled appointment and not simply on demand (this is commonly done already in most advisory firms).

- Offer set meeting time slots during normal business hours at specific times of the day (like the strategy mentioned above, this is very common already amongst many advisory firms).

- Provide service response times, stating that clients will hear from the advisor within a certain time period (such as within 24 hours). While this provides a service guarantee (within 24 hours), it also grants the advisor permission to not respond until the end of the 24-hour window, allowing the advisor to prioritize their workload (including other more urgent client requests first) while setting a clear expectation for the client when their question will be answered.

Uncompromised Reduction:

- Incentivize clients to schedule meetings during traditionally quiet times of the day or year by offering to do additional planning. For example, an advisor could offer to do a very in-depth end-of-year tax planning analysis if the client schedules their meeting by October 31st. If the client waits to schedule their meeting after that date, then the advisor may do a less in-depth analysis in the more hurried final two months of the year.

Low-Cost Accommodation:

- Instead of needing to contact the advisor to discuss every possible planning idea, a financial planning portal could be rolled out to allow clients to run some basic planning scenarios on their own. By developing a strong online presence, it allows clients to get some guidance or insight when the timing is best for them.

- A newsletter (either written by the advisor or a third-party newsletter service) could be used to communicate many of the points the advisor would traditionally raise in a client meeting. In one interesting case, an advisor leveraged fpPathfinder flowcharts in the firm’s newsletter to explain specific planning strategies and used Holistiplan tax analysis software to scan the client’s tax return and develop client-specific recommendations based on the topics covered in the newsletter. By doing this in combination, the advisor was able to bring this planning opportunity to all of the clients in a fraction of the time it would have taken for the advisor to talk to and analyze one client at a time.

Managing Request Variability – When Clients Make (Unique) Demands

A lot of financial advisors, especially those just starting out, will do just about anything their client asks and will work with just about any client that’s willing to pay them. But when every client is different and makes different requests, the advisory firm not only fails to gain economies of scale as it grows, it can become less efficient by needing to accommodate an ever-widening range of client requests.

Alternative strategies include:

Classic Reduction:

- When a client asks for a custom report or a kind of analysis that the advisor does not typically prepare, the advisor could say “no” along with a reason why it is not possible (producing such customized reports for all clients would necessitate raising the client’s fees). Perhaps the advisor could just shift the request by showing them how an existing standard report will mostly (and hopefully sufficiently) meet the client’s needs.

- If a prospective client wants to work with the advisor in a specific way, but the unique needs of that client are outside the scope of what the advisor regularly deals with, the advisor could refuse to take them on as a client and refer them to another advisor that is better suited for their needs.

- An advisor could have certain requirements of clients in order to work with them. A common example is to have asset minimums in place, which helps to make sure that clients have at least somewhat similar needs (at least when it comes to the potential complexity of their portfolio). Another example is advisory firms that only work with “delegators” who agree to fully delegate their entire portfolio to the advisory firm (to eliminate the accommodation requests of coordinating the advisor’s ‘portion’ of the portfolio with other outside advisors or investments).

Uncompromised Reduction:

- A customized software solution could be purchased to accommodate the client’s unique requests and then used as a basis for finding other similar clients. For example, an advisor could offer to do a pre-IPO stock option analysis for the client using StockOpter, and then ask the client for referrals to other clients at the firm that might also be interested in a similar analysis of their equity compensation as well.

- In our industry, “engineer” clients are sometimes considered to be difficult because they are very technical and specific. Instead of simply accommodating or dealing with the request, the advisor could switch to a more detailed cash-flow-based financial planning software that provides a detailed audit trail for engineers (e.g., MoneyTree), create a standardized batch of detailed reports, and then seek out other engineer clients who may have the same preferences (which could then result in a more efficient advisory firm).

Low-Cost Accommodation:

- Clients who regularly request updates to their performance reports could be granted access to a performance reporting portal (e.g., Orion) that allows them to create and view their own performance reports on-demand 24/7/365, without ever needing to contact the advisor.

- Support tools can be implemented to shortcut the process of analyzing and making recommendations for ‘one-off’ client scenarios that the advisor may be facing for the first time. For instance, FP Alpha can help scan common client documents to identify talking points for the advisor, and checklists and flowcharts developed by fpPathfinder can provide a turnkey system to ensure that planning issues are identified.

Capability Variability – When Clients Need Different Levels Of Educational Support

As with many of the other variables, a common (classic accommodation) strategy is to work with clients regardless of their own financial capability. Over time, though, clients that ‘demand’ more client education become more stressful to serve as they are more time-consuming than less-educationally-intensive clients who may otherwise pay the same fee. And most advisor fee schedules aren’t built to help clients with budgeting or other tasks to help increase the client’s financial literacy capability.

Alternative strategies include:

Classic Reduction:

- Similar to request variability, the advisor could have certain requirements to ensure that the client has a level of knowledge before being taken on as a client. For instance, the advisor will only work with clients who already have at least 15 years of experience with a portfolio and who have been through at least one prior bear market (and still want to invest).

Uncompromised Reduction:

- Based on background, education levels, and a variety of other factors, the capability variable may actually be a sign of a niche market opportunity. For instance, if the advisor is routinely referred to the children of their affluent clients to help educate them on finances and the wealth they may someday inherit, the advisor could develop this into a standardized offering for multi-generational families that includes cultivating the next generation to be good stewards of the wealth they will inherit, for which the firm charges a family-wide advice fee.

Low-Cost Accommodation:

- An advisor could offer a standardized course or educational series for clients (or partner with someone else) to help educate them on the basics of personal finance. The idea is to have a system in place to bring clients with too little knowledge of personal finance to a level where the advisor can provide guidance, but not have to spend a lot of time educating each client on a one-on-one basis.

Effort Variability – When Clients Might Not Put In The Time

The classic accommodation approach to clients who don’t want to take the time and put effort into the advice process is for the advisor to simply take everything off the client’s plate and do all the work for them. Which can result in anything from pre-filling a client’s paperwork for them, to going to their house to help sort through documents for data-gathering purposes, or even going along with them to meetings with other professionals or to wait in line for them at the Social Security Administration’s office!

Alternative strategies include:

Classic Reduction:

- Establish “Engagement Standards” that clearly state the expectations of the client to be a part of the advisor-client relationship, and to what extent the advisor will (or will not) assist the client. This sends a strong message to the client about how far the advisor will (or won’t) go to assist the client.

Uncompromised Reduction:

- Embracing the variability of effort is a possible niche that advisors could consider. An advisor could build a system to cater to clients who are too busy to handle their finances. Tools like bill.com allow advisors to even assist with some bill payment systems for their clients.

- Clients who are resistant to taking the time to engage in the data-gathering process could instead be offered a “Get Organized” meeting where the firm will create the filing and sorting system for them, help them go through the organizational process, do the work to get them more organized… and then sell the “Get Organized” service to other prospective clients who want help to get more financially organized (and otherwise won’t do the work themselves).

- An idea of bringing some normative comparisons into the firm could help encourage clients to be responsive. Easy options could entail telling clients that it usually takes (just) 20 minutes to complete a particular step or exercise. Betterment and Mint have even explored this option of providing some elements of peer comparison for their users to see how well they are doing relative to people like them, in order to encourage them to take the next step of effort.

Low-Cost Accommodation:

- Many technology tools can be used to make it easier for clients to complete crucial steps in the planning process and reduce the required effort. For instance, the use of e-signatures such as DocuSign can help speed up administrative tasks for clients and reduce the friction to move forward.

- A new technology solution called Knudge can automate the process of reminding clients to complete certain tasks, making it easier to give challenging clients the extra nudges they need to get key tasks done when they’re otherwise reluctant to do so.

Subjective Preference Variability – When Clients Want What (Only) They Want

The classic accommodation approach to handling clients who each want something different is to give it to them, creating tailored experiences for each client based on their own unique preferences and interests. As with most types of client variability, though, accommodating every request in its own unique way can be difficult and costly to scale.

Alternative strategies include:

Classic Reduction:

- Just because the client asks for a customized report doesn’t mean the firm has to produce it. In some cases, it may just be a matter of reminding the client that their comprehensive financial plan is still developed to their individualized needs and circumstances, even if the reports that are produced are “standard”.

Uncompromised Reduction:

- Many “client-specific” preferences form the basis for niche or specialized services. For instance, if a client has a strong preference for investing in accordance with certain socially responsible themes, the firm could create a series of ESG model portfolios and roll out a Shareholder Engagement initiative as part of the specialized offering for clients.

Low-Cost Accommodation:

- When clients have especially high service demands and insist on fast response times, it can be difficult for an advisor with a full plate of clients to respond quickly. One alternative is to create a “private” email address – such as [email protected] – that top clients can use, which is automatically forwarded to the entire client service team, to ensure that someone responds to the client’s request as quickly as possible.

There are several themes that emerge from Frances Frei’s work that showcase how service-based businesses are retooling how their services are provided to clients and customers to manage the challenges of client variability.

First, technology can increasingly be used as a ‘low-cost’ accommodation strategy, providing self-service or automation tools that allow clients to get what they want on their own terms (but not add additional steps for the advisor).

Second, for those who want to accommodate clients, consider going “all-in” to embrace the variability, provide an in-depth solution to the need… and target other prospective clients who may have this same variability, which can become a niche the advisor can serve to further differentiate themselves. And over time, focusing on such a niche can actually reduce client variability, because the advisor only takes on clients with those specific variables (and already has unique but systematized solutions to serve them).

The third theme is to recognize that it’s OK to say “no” when clients ask for extensive customization… because in the end, not all advisory firms are truly priced for such accommodations, and the firm shouldn’t feel any obligation to provide a level of service that clients are not actually paying for (and would decline if the firm ‘adjusted’ their pricing accordingly). It’s only natural for clients to ask to get more while paying less, but that doesn’t mean a firm can, should, or has to accommodate all such requests just because they’re made. The chart below summarizes many of the different tactics a firm can consider to address the different kinds of client variability.

Ultimately, though, the key point is simply to understand that one of the biggest constraints to advisory firms getting more efficient as they grow is that taking on an ever-widening range of clients can undermine the firm’s scalability by introducing more and more client variability. The framework proposed by Frances Frei offers compelling methods to handle the emergence and compounding of client variability, either to help ensure that it recognizes when it may need to raise fees commensurate with the level of client-specific accommodations it is making, or in how to manage the never-ending stream of accommodations that clients may request so that the advisory firm does not become inefficient as it grows in size.

Leave a Reply