Executive Summary

When it comes to the decision of where to live in retirement, some clients might assume they will remain in their current home for the duration of their lifetime, while others might quickly gravitate toward a senior-specific living arrangement (e.g., a 55+ living community or a Continuing Care Retirement Community [CCRC]). However, given that the decision of where to live in one's later years also has implications for how they will receive care as they age, this choice can be more complex than it appears on the surface, creating an opportunity for financial advisors to support clients in thinking through the full implications (both financial and lifestyle) of this issue.

In this guest post, Kathleen Rehl – a former financial advisor with significant professional and personal experience in navigating later-life transitions – examines the housing choice issue by shifting the advisor-client conversation from "Which community should we choose?" to the more fundamental question of how housing and care will be delivered, coordinated, and paid for during a client's 70s, 80s, and beyond.

Given the number of later-life housing and care options available, financial advisors can help clients analyze their choices (and the tradeoffs involved) on a variety of factors, both qualitative (e.g., housing stability, care coordination, and social and community infrastructure) and financial (e.g., upfront costs and ongoing cost predictability). For example, a 55+ rental community requires minimal upfront cost but requires the client (or family members) to manage their care coordination, while a CCRC itself handles care transitions, but often at a higher upfront cost.

At a more fundamental level, financial advisors can offer value for their clients by starting this conversation in the first place, at an age (perhaps in the client's late 60s or early 70s) when clients are typically healthier, more financially flexible, and more likely to meet admission criteria than they would be as they approach their 80s or 90s. Given the potential sensitivity of this topic, advisors can help clients prepare for the discussion by introducing the topic gently in a pre-meeting agenda and using a short discovery checklist to surface client values, fears, family dynamics, and tolerance for uncertainty. In addition, by coming to the meeting with data on the estimated costs of local options, advisors can better lay out the financial tradeoffs involved with different later-life housing and care options.

Ultimately, the key point is that because clients might not have thought through the full implications of where they will live and how it affects how they will receive care (and how housing transition decisions will be made as their care needs evolve), financial advisors can play an important role in helping clients think through both the lifestyle and financial implications of different options for their later years. Which could allow clients to maintain their independence, reduce future stress, and make intentional decisions before health issues restrict their options.

When clients ask about later-life housing options, they often frame the question narrowly: "Should we just age in place?" or "Which community should we choose?" or "Is a CCRC (continuing care retirement community) worth the cost?" But those questions are downstream of a much more fundamental planning issue.

In reality, clients are not simply choosing a building or a lifestyle – they are choosing how housing and care will be delivered, coordinated, and paid for during their 80s and 90s. Until advisors explicitly surface that broader decision, these choices are easy to misclassify as optional lifestyle upgrades rather than as legitimate housing-and-care strategies that belong inside the financial plan. This is especially true when discussing CCRCs, as it can be difficult to properly evaluate the benefits and features of a specific CCRC –or whether a CCRC is even appropriate for a particular situation – within the broader housing-and-care landscape.

Reframing The Question: Housing And Care, Not Just Housing

From a planning perspective, later-life housing decisions involve cash flow, health risks, longevity, family dynamics, and logistics. However, many plans implicitly assume "aging in place" as the default path without stress-testing how care will actually be provided if health declines.

When reframed correctly, clients are evaluating several structurally different approaches:

- Aging in place, often supplemented by paid home care and informal family caregiving

- Rental or 55+ communities, which may simplify housing but still require external care coordination

- CCRCs, which bundle housing, services, community, and prioritized access to care within one system

- Assisted living, skilled nursing, or memory care, typically accessed reactively after a health event and driven primarily by care needs rather than lifestyle preferences

Each option answers the housing-and-care question differently – particularly regarding cost predictability, care logistics, and who bears the risk as needs increase. The advisor's role is not to steer clients toward a particular choice, but to clarify that these choices represent fundamentally different risk structures, care options, and lifestyle paths, not just interchangeable living arrangements.

This distinction is becoming increasingly crucial as demographic trends alter how people plan for later life. Clients are living longer, enduring more years with chronic conditions, and often facing widowhood or aging alone without nearby adult children.

In this context, decisions about housing and care are no longer just personal choices; they are vital to whether a client's plan can withstand stress.

Demographic Shifts Shaping Later-Life Housing

The U.S. is experiencing a sustained demographic shift toward an older population, with more than 61 million adults aged 65 and older in 2025, according to the United States Census Bureau. The projected population of those over age 65 in the U.S. by 2050 is expected to reach around 82 million. Approximately 70% of adults who reach age 65 will require some form of long-term care during their lifetime, driving steady demand across settings from aging-in-place to high-acuity care. The National Investment Center for Seniors Housing & Care (NIC) reports that there are about 1,900 CCRCs in the U.S.

What CCRCs Are – And Why They're Hard To Evaluate

With a better understanding of the broader housing and care structures available, CCRCs can be assessed more precisely. At their core, CCRCs (also called Life Plan Communities) are integrated housing-and-care systems that usually provide independent living with on-campus access to higher levels of care as needs evolve.

What complicates planning analysis is that CCRCs are not standardized products. They vary widely by:

- Contract structure (life care, modified, fee-for-service)

- Entrance fees and refundability provisions

- Monthly fee levels and escalation policies

- How and when higher levels of care are priced and accessed

- Potential tax treatment of portions of fees as medical expenses

From an advisor's perspective, CCRCs are complex because they combine elements of housing, insurance, and long-term care – yet they are regulated and marketed differently from all three. Without a structured comparison framework, it's easy to either oversimplify ("it's just expensive housing") or avoid the analysis altogether.

Once the structural housing-and-care decision is made, clients can then evaluate individual communities based on lifestyle, learning opportunities, wellness offerings, and personal fit.

The Practical Frictions Advisors Rarely See On Paper

Even when the numbers seem feasible, real-world implementation introduces obstacles that can significantly impact outcomes. Clients might encounter multi-year waiting lists, health underwriting that restricts eligibility, and complicated timing issues related to selling a long-time home while keeping liquidity for an entrance fee. Some temporarily hold two residences, which increases short-term cash flow pressure. Others find it emotionally difficult to let go of a home or identity connected to independence.

These frictions matter because they often influence when a housing-and-care decision remains viable – and whether it remains a proactive choice or becomes a reaction to crisis. Advisors who understand these dynamics can help clients plan proactively, rather than forcing later-life housing decisions into the plan only after health or caregiving needs have already escalated.

As a financial advisor, I researched CCRCs for many years on behalf of clients deciding where – and how – to live the later years of their lives. I went through that same process myself several years ago. What struck me most was how many planning frictions never appear on spreadsheets. Coordinating the timing of a home sale, carrying two residences temporarily, navigating health underwriting and admission criteria, and emotionally letting go of a long-held home all required more lead time – and more cognitive bandwidth – than most clients expect. Experiencing the decision from both sides of the table reinforced for me why housing-and-care choices are best explored proactively, while clients still have the flexibility to choose rather than react.

Once CCRCs are seen not just as lifestyle enhancements but as comprehensive housing-and-care packages, the next step is to examine how they influence a client's overall risk profile – and why, for some clients, this integrated system acts as a form of later-life safety net.

My perspective on these tradeoffs is also shaped by personal caregiving experience. Early in my prior marriage, my late husband's frail father lived with us for two years. Later, I helped care for my mother after my father's death and supported her transition into a continuing care retirement community. I also cared for my husband during his cancer journey. Those experiences made the hidden costs of caregiving – emotional, logistical, financial, and physical – impossible to ignore.

Today, like many residents in my own community, I am acutely aware that my adult children lead full, engaged lives of their own. A central goal of my planning has been to avoid turning them into default caregivers or crisis coordinators later. That motivation – shared quietly by many older adults – rarely appears in financial projections, yet it strongly influences how clients evaluate housing-and-care strategies when given space to articulate it.

Why CCRCs Function As A Bundled Safety Net – Not Just Expensive Housing

When CCRCs are understood as integrated housing-and-care systems rather than lifestyle choices, their role in a financial plan becomes clearer. The primary question is no longer whether a CCRC is "worth the cost", but how its bundled structure shifts later-life risks compared to aging in place or other housing options.

From an advisor's perspective, CCRCs are best evaluated not by amenities or aesthetics, but by how effectively they transfer, pool, or reduce risks that otherwise fall squarely on the client – and often on their spouse or family.

How CCRCs Change The Later-Life Risk Profile

Aging in place is often seen as the most affordable and least disruptive option. However, that view often misses where risks actually build up over time. As health needs grow, staying at home usually means adding paid home care, coordinating medical and non-medical services, and depending on informal caregivers – often a spouse who may also be getting older or adult children who might live far away.

CCRCs alter this dynamic by bundling several risk elements into a single system:

- Care coordination risk shifts from family members to the institution.

- Transition risk between levels of care decreases as moves happen within one community.

- Care access risk is reduced through priority placement rather than reactive searches.

- Social and functional decline risks are addressed through built-in community and wellness infrastructure.

For couples, this arrangement can greatly lessen the caregiving load on the healthier spouse. For widowed or solo elders, it can serve as a substitute for informal support networks that may no longer be available. And for clients without nearby adult children, it can offer continuity that would otherwise require complicated – and often costly – external coordination.

Importantly, these benefits are not guaranteed or uniform across all CCRCs. Contract type, pricing structure, and the organization's financial strength matter greatly. But conceptually, CCRCs function less like housing and more like a bundled safety net designed to smooth later-life volatility.

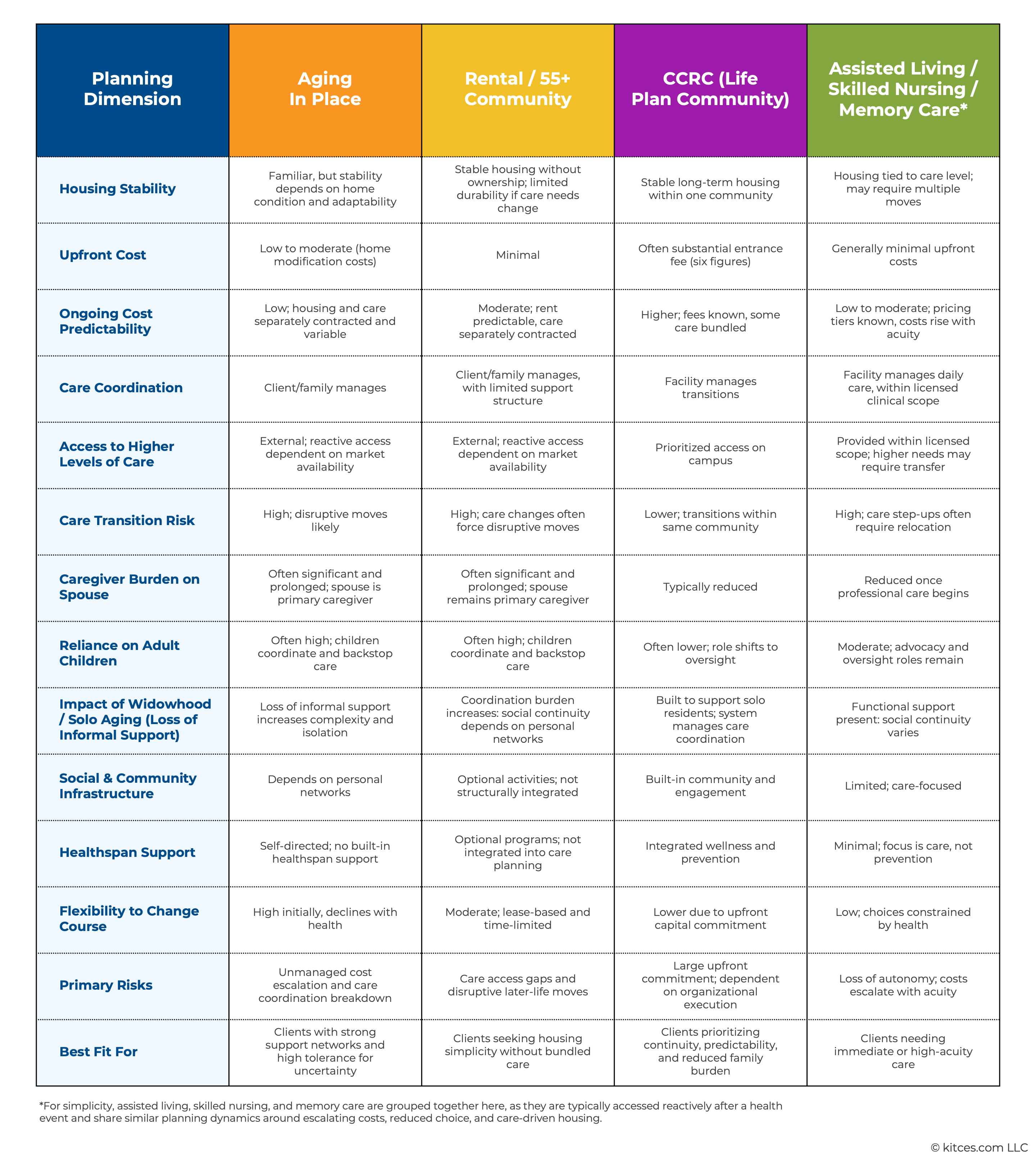

To clearly evaluate that tradeoff, advisors need a method to compare structurally different options on equal ground. One effective solution is a Housing & Care Matrix, which compares aging-in-place, rental or 55+ communities, CCRCs, and assisted living facilities side by side across key planning dimensions.

Rather than focusing solely on monthly costs, the matrix examines factors such as:

- Financial risk and predictability (cost volatility, exposure to care escalation)

- Care logistics (who coordinates care, how transitions occur, access timing)

- Lifestyle and community (social engagement, daily support, purpose)

- Impact of widowhood or solo aging (care continuity, burden on others)

In addition to structural and logistical considerations, CCRCs can also introduce meaningful tax-planning implications that affect their after-tax cost.

A Commonly Overlooked Tax Consideration: Medical Expense Deductibility

An important – but sometimes overlooked – aspect of CCRC planning is that a portion of certain fees may qualify as deductible medical expenses, depending on the resident's contract type.

Nerd Note:

Over the years, the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) has issued several private letter rulings (67-185, 75-302, 76-106, and 76-481) recognizing that a substantial portion of the entrance fee or monthly service fee paid to a continuing care retirement community can be classified as a prepaid medical expense. As a result, a portion of the entrance and monthly fees paid to a CCRC may be eligible for a tax deduction on the resident's tax return. These expenses are deductible only to the extent that they exceed a certain percentage of the resident's adjusted gross income.

In many life plan communities, this can include part of the upfront entrance fee as well as a portion of ongoing monthly service fees, depending on the community's allocation and the resident's individual tax situation.

Importantly, residents may have flexibility in how the deductible portion of the entrance fee is applied for tax purposes, which can materially affect cash flow and tax planning outcomes. Common approaches include taking the deduction in full in the year the entrance fee is paid – potentially useful in a high-income year or following a liquidity event – or amortizing the deductible portion over time to align with future income needs or ongoing itemized deductions.

In addition, the medical portion of the monthly service fee may generate an ongoing annual deduction, creating a recurring tax benefit that can partially offset the higher headline cost of CCRC living.

For many clients, the tax treatment does not change whether a CCRC is affordable in the context of their financial plan – but it can meaningfully influence when and how the transition is funded.

Because deductibility depends on IRS rules, community-specific allocations, and the resident's broader tax picture, decisions about timing and treatment are best made in coordination with the client's CPA.

To help advisors and clients compare structurally different housing-and-care strategies on equal footing – beyond surface-level cost comparisons – the following Housing & Care Matrix highlights how each option distributes financial, caregiving, and coordination risks over time, including care continuity and the burden placed on others – particularly adult children or informal caregivers.

The Housing And Care Matrix: Comparing Later-Life Housing-And-Care Strategies

The matrix below helps advisors and clients compare structurally different housing-and-care strategies by showing who bears cost, coordination, and transition risk as needs evolve.

Used thoughtfully, the matrix shifts the advisor-client conversation away from whether a particular option is "worth the cost" and toward which risks clients are willing – or unwilling – to manage themselves over time.

Using Specialized Modeling Tools (When Appropriate)

For some clients – and some advisors – the qualitative insights from a Housing & Care Matrix naturally raise a follow-on question: "Can we model this more precisely?"

In those cases, specialized financial modeling tools can help deepen the analysis without replacing the advisor's judgment or the broader planning conversation.

One example is the myLifeSite Financial Calculator, developed by Brad Breeding, CFP®, Managing Partner of myLifeSite. The tool is designed specifically to evaluate financial readiness for moving into a continuing care retirement community.

The calculator allows advisors and clients to explore a wide range of assumptions – including CCRC contract types, entrance fee and refund levels, years spent in different care levels, the presence or absence of long-term care insurance, financial assets, ongoing monthly fees, and more.

For analytically inclined clients, the value is not just the output, but the transparency. The tool produces a multi-page report that shows how the numbers are built, and it allows advisors to quickly adjust inputs to explore "what-if" scenarios as circumstances or preferences change.

Used thoughtfully, tools like this can complement the Housing & Care Matrix by translating structural tradeoffs into concrete projections – particularly for clients who want to see how different assumptions affect long-term sustainability.

Importantly, these tools are not substitutes for comprehensive financial planning or for the advisor's role as guide and translator. They work best when embedded within a broader process that considers values, risk tolerance, family dynamics, and timing – not just mathematical outcomes.

Why Timing Matters More Than Clients Expect

One of the most consistent planning insights to emerge from CCRC analysis is that the best time to explore these options is often when clients feel "too young" to need them. Late 60s and early 70s clients are typically healthier, more financially flexible, and more likely to meet admission criteria than they would be as they approach their 80s or 90s. They also have the emotional bandwidth to evaluate options thoughtfully rather than under duress.

Waiting until a health event forces the decision often narrows choices dramatically. Admission options may be limited, waiting lists may be prohibitive, and family members may be pulled into crisis-driven caregiving roles. At that point, the decision is no longer strategic – it is reactive.

Framed differently, later-life housing decisions resemble a trapeze move: clients must let go of one phase of life before fully landing in the next. Advisors who help clients prepare for that moment – rather than reacting after the fall – add significant value that extends well beyond the numbers. Yet despite the stakes and the advantages of early planning, these conversations rarely occur.

Framed differently, later-life housing decisions resemble a trapeze move: clients must let go of one phase of life before fully landing in the next. Advisors who help clients prepare for that moment – rather than reacting after the fall – add significant value that extends well beyond the numbers. Yet despite the stakes and the advantages of early planning, these conversations rarely occur.

Once CCRCs are evaluated as a risk-management strategy using a consistent framework, the remaining challenge is implementation. The next step is translating this analysis into a practical, repeatable process that advisors can integrate into their ongoing planning work.

In conversations with residents and clients, a consistent pattern emerges: many people reach their late 70s having never meaningfully discussed later-life housing and care with their estate planner or financial advisor. This gap is rarely the result of neglect. More often, clients feel "too young" to engage the topic, while advisors hesitate to raise an issue they know can feel emotional, premature, or outside their day-to-day technical focus. Compounding the challenge, continuing care retirement communities are frequently misunderstood – often conflated with nursing homes – making the conversation even easier to defer. The result is an unspoken planning blind spot: a decision that materially affects financial security and caregiving dynamics as needs evolve.

Importantly, this silence does not reflect a lack of caring or fiduciary intent. It reflects the absence of a clear framework for addressing housing and care before urgency sets in. When advisors lack tools, language, or repeatable processes, the path of least resistance is to wait. Yet waiting is itself a decision – one that often shifts choice into crisis.

A Repeatable Advisor Process for Integrating Housing And Care Into The Plan

Once later-life housing is framed as a modellable housing-and-care decision – and evaluated using a consistent comparison framework – the remaining challenge is execution. Advisors need a process that fits naturally into ongoing planning conversations without turning housing into a one-off, crisis-driven discussion.

The goal is to normalize housing and care planning as a standard element of fiduciary advice, much like retirement income or insurance analysis. A simple before-during-after meeting structure helps make that work repeatable.

Before the Meeting: Prepare And Frame The Conversation

Effective housing-and-care planning begins before the client ever sits down at the table. Advisors can lay the groundwork by integrating this topic into regular review cycles.

Key preparation steps include:

- Add "Housing & Care in Later Life" to the standing agenda for clients in their late 60s and 70s

- Gather baseline local data on aging-in-place assumptions, rental or 55+ communities, and CCRCs

- Customize the Housing & Care Matrix with local cost ranges and care availability

- Send pre-meeting language that introduces the topic gently, framing it as long-range planning rather than imminent change

- Use a short discovery checklist to surface values, fears, family dynamics, and tolerance for uncertainty

This advanced framing reduces defensiveness and signals that housing decisions are part of prudent planning – not a reaction to decline.

During The Meeting: Compare, Model, And Discuss Tradeoffs

In-meeting discussions are where the Housing & Care Matrix becomes most powerful. Rather than debating individual facilities, advisors can walk clients through how each option distributes financial, caregiving, and coordination risks.

During the meeting, advisors can:

- Review the Housing & Care Matrix collaboratively, focusing on risk structure rather than amenities

- Discuss cash-flow implications, including entrance fees, baseline monthly costs, and potential care escalation

- Model scenarios that incorporate:

- Home-sale timing and liquidity needs

- Longevity and widowhood stress tests

- Long-term care insurance or self-funding assumptions

- Use tailored scripts for different client situations:

- Healthy couples planning ahead

- Widows or solo agers prioritizing continuity and support

- Adult children participating in care discussions

- Others

This approach reframes the conversation from "Is this too expensive?" to "Which risks are we willing – or unwilling – to manage ourselves?"

After The Meeting: Document, Stress-Test, And Implement

After the meeting, advisors translate insight into defensible planning work. This step is especially important for large, irreversible decisions where documentation and clarity matter.

Post-meeting follow-through typically includes:

- Building side-by-side scenarios in planning software that reflect the options discussed

- Stress-testing plans for longevity, care escalation, and changes in marital or health status

- Documenting tradeoffs and assumptions as part of the fiduciary process

- Coordinating with a local referral bench, such as:

- Aging Life Care managers

- Elder-law attorneys

- Senior-focused real estate professionals

- Positioning the advisor as a guide and translator, not a certifier or recommender of specific communities

Over time, this process allows housing-and-care decisions to evolve as circumstances change – without turning every discussion into a crisis response.

Sample Advisor Scripts For Housing And Care Conversations

Because housing-and-care decisions are emotionally charged, the way advisors introduce and frame these conversations matters. The following sample scripts illustrate how advisors can normalize housing-and-care planning across common client situations – without implying urgency or steering clients toward a particular outcome.

Healthy Married Couple (Late 60s – Early 70s)

Goal: Normalize early planning without implying urgency.

- "I want to zoom out for a moment and talk about housing and care later in life – not because anything needs to change now, but because this is one of the biggest planning decisions people make in their 70s and 80s".

- "Most plans assume you'll age in place, but that's really a default, not a decision. Over time, all couples end up choosing how care will be coordinated if one of you needs help".

- "What I'd like to do is compare a few broad housing-and-care approaches – not specific communities yet – so you understand the tradeoffs well before timing or health forces the issue".

Why this works: It frames the conversation as proactive planning rather than prediction or pressure.

Couple With Uneven Health Profiles

Goal: Address asymmetry without creating fear or blame

- "One thing I often see with couples is that care planning becomes more complex when one partner is likely to need help before the other".

- "This isn't about expecting something to happen – it's about deciding how much caregiving responsibility each of you wants to carry if circumstances change".

- "We can compare a few housing-and-care approaches and look specifically at which ones protect the healthier spouse from becoming the default caregiver".

Why this works: It names the issue directly while keeping the focus on mutual planning, not prognosis.

Solo Ager (Including Widowed Individuals)

Goal: Emphasize autonomy, continuity, and reduced coordination burden

- "When someone is planning on their own, housing decisions tend to carry extra weight – not just financially, but logistically".

- "A key question becomes: Who coordinates care if something changes, and how many decisions would you want to make during a stressful moment?"

- "Let's compare a few different housing-and-care structures and see which ones give you the most control now, while simplifying things later if support is needed".

Why this works: It affirms independence while acknowledging real-world complexity.

Client Strongly Attached to Aging In Place

Goal: Respect preference while stress-testing assumptions

- "Many people tell me they want to stay in their home as long as possible, and that may absolutely be the right choice for you".

- "What I'd like to do is stress-test what aging in place would look like if care were needed – not to change your mind, but to make sure the plan truly supports that goal".

- "We'll compare it side by side with a few other approaches so you can see which risks you're choosing to manage yourself and which ones you might prefer to outsource".

Why this works: It validates the client's preference while preserving analytical rigor.

Client Concerned About CCRC Cost

Goal: Reframe cost as risk allocation rather than price

- "They often look expensive when viewed purely as housing".

- "From a planning perspective, though, the more relevant question is which risks are prepaid, and which remain open-ended".

- "Let's compare this to aging in place and assisted living – not just on monthly cost, but on cost predictability, care access, and the impact on family involvement".

Why this works: It avoids defensiveness and elevates the conversation.

Adult Children Present in the Meeting

Goal: Balance client autonomy with family reassurance

- "I want to be clear that this conversation is about supporting your parents' goals, not making decisions for them".

- "What we're really comparing is how different housing-and-care approaches affect everyone involved – independence for your parents, predictability for the plan, and coordination demands on family".

- "Having this discussion early often reduces stress for everyone later, even if no changes are made now".

Why this works: It protects client agency while acknowledging family dynamics.

Introducing the Housing & Care Matrix

Goal: Transition smoothly from conversation to framework

- "Rather than talking about these options in the abstract, I use a simple matrix to compare different housing-and-care approaches side by side".

- "This isn't about picking a winner – it's about seeing how each option handles cost volatility, care logistics, and changes like widowhood or cognitive decline".

- "We can update this over time as your priorities or circumstances change".

Why this works: It lowers the stakes and reinforces planning as an iterative process.

Closing the Conversation

Goal: Reduce pressure and reinforce optionality

- "Nothing needs to be decided today".

- "The goal is simply to make sure your plan reflects real choices rather than assumptions, so that if circumstances change, you're responding from clarity rather than urgency".

Why this works: It leaves clients grounded and in control.

Additional Resources

A Woman on the Inside

For advisors who want a practitioner-informed perspective on CCRCs grounded in lived experience, this piece offers context on how integrated housing-and-care systems function from the inside – without positioning CCRCs as the right choice for every client.

Your Best Path Forward: A Practical Guide to Navigating Senior Living Options and Planning

For clients seeking a broad introduction to late-life housing options, this consumer-oriented resource outlines common pathways and tradeoffs to support informed conversations with family members and advisors.

Newsweek – America's Best Continuing Care Retirement Communities (2026)

For advisors and clients seeking a broad, third-party overview of CCRCs across the United States, this annual, survey-based ranking highlights communities based on resident experience, peer recommendations, and quality indicators. It can serve as a starting point for identifying communities to explore further, alongside deeper due diligence on contracts, financial strength, governance, and fit with housing-and-care priorities.

Final Thoughts

Later-life housing decisions are among the largest and most consequential choices clients will make – financially, emotionally, and logistically. Yet they are often left unexamined until a health event forces action, narrowing options and increasing stress for everyone involved.

By treating housing and care as a core planning issue rather than a lifestyle afterthought, advisors can help clients move from default assumptions to intentional choices. Frameworks like the Housing & Care Matrix, supported by thoughtful modeling and clear communication, allow advisors to guide these decisions with clarity, compassion, and fiduciary rigor.

The value advisors provide in this context is not in recommending a particular solution, but in helping clients understand the tradeoffs, timing, and risks – early enough that the decision remains a choice. When done well, that guidance can preserve autonomy, reduce future family burden, and align later-life decisions with the client's broader financial and life goals before urgency narrows choice.

Leave a Reply