Executive Summary

Taking time away from the office can have many benefits for advisors, from the personal (e.g., spending time with family and exploring new places) to the professional (e.g., resting and recharging to help prevent burnout). At the same time, being away from work (whether it is working fewer hours during the week or taking full vacation days off) means having less time for client engagement, business development, and other firm activities. This raises the question of how advisors can most effectively balance their work obligations with the benefits of taking time off.

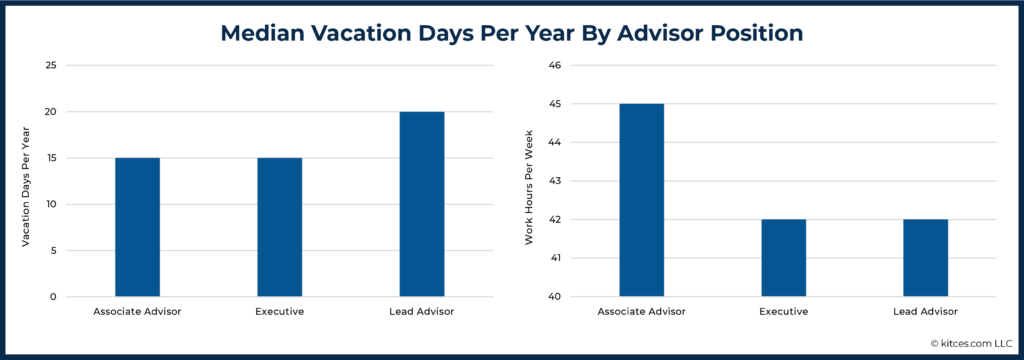

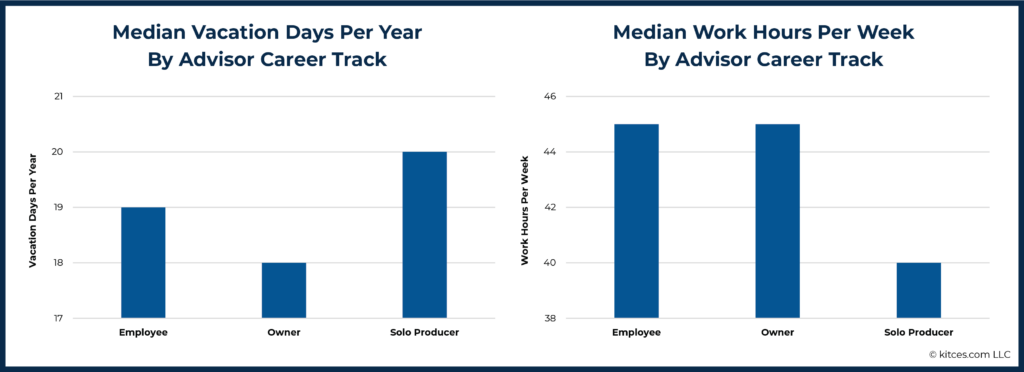

According to the latest Kitces Research study on Advisor Wellbeing, the median number of weekly hours worked and annual vacation days taken vary by position, where associate advisors tend to work more hours than lead advisors or executives, and where lead advisors tend to take more vacation than their counterparts. Further, median hours worked and vacation days taken also vary based on the advisor's status within the firm. For example, firm owners and employees work a median of 45 hours per week, while solo producers work a median of 40 hours per week. In addition, solo producers also take more vacation days than owners and employees.

These differences could be related to job experience and tenure, but they may also be related to differences in job function of each role, which can have a large impact on how advisors feel they can regulate their work hours and vacation time. For instance, even though some advisory firm executives may have fewer client advisory responsibilities, their job responsibilities include managing their staff and the office itself, which could be one reason why they take fewer vacation days than lead advisors.

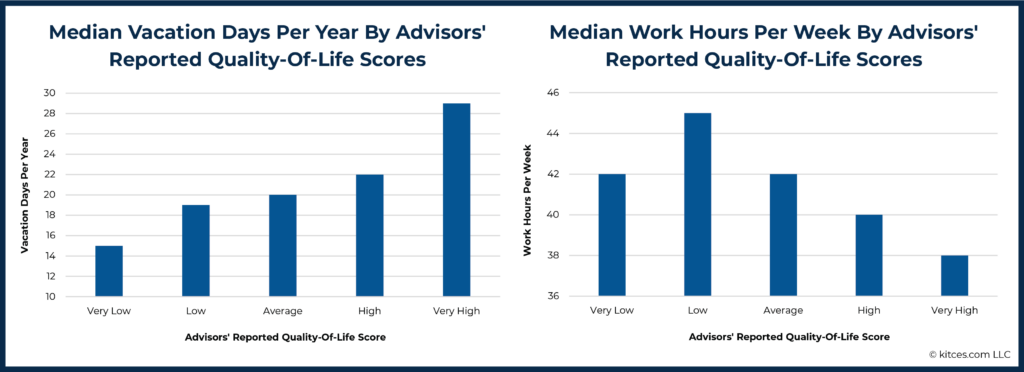

Further, work hours and vacation days appear to be correlated with adviser wellbeing. For instance, the Kitces Research study found that advisors who reported very low quality-of-life scores took about 15 vacation days each year and worked about 43 hours per week. Advisors with very high quality-of-life scores took 29 vacation days each year and worked 38 hours per week, suggesting that advisors who work long hours may not be offsetting their regular work hours with vacation days, which could be a source of relaxation.

Given the various benefits of having time away from work, advisors have several options to reduce their weekly work hours and add vacation days to their calendar. For instance, designating a schedule based on realistic working hours can help them structure their time in a way that will help them meet their goal. Also, setting expectations for clients is especially important, both in terms of vacation days (by letting them know at the beginning of the engagement that the advisor will not be available during certain vacation periods) and during the workweek (which advisors can do by including their availability for replies in their email signature). In addition, bringing on new employees to share the work burden can free up time for firm owners, but they need to be careful not to allow this newfound time to be consumed by management responsibilities!

Ultimately, the key point is that taking time away from the office is a key contributor to an advisor's overall wellbeing. And for advisors who would like to work fewer hours per week or take more vacation days (or both!), setting clear expectations with clients and co-workers is an important first step toward creating more high-quality free time!

Being An Advisor Is Intensive Work, And Managing Sustainable Working Hours Supports Their Wellbeing

In the latest Kitces Research study on Advisor Wellbeing, we examined how an advisor's work habits impact their wellbeing and, with summer just around the corner, how important sustainable work hours and vacations are for advisors to maintain healthy stress levels.

To better understand what it means to work healthy hours and take healthy vacations, we started by examining how advisors in different roles are currently working and taking vacation time. Because the reality is that advisors work in many different positions and tend to take vacations in different ways depending on their roles. For instance, associate advisors tend to work more hours (45 hours per week) than lead advisors or executives (both reported working 42 hours per week), and lead advisors tend to take more vacation days (20 days per year) than their counterparts (15 days per year).

While these differences could be related to job experience and tenure, they may also be related to differences in the job function of each role. For instance, even though some advisory firm executives may have fewer client advisory responsibilities, their job responsibilities also include managing their staff and the office itself, which may be why they took less vacation than lead advisors. This may suggest that, in addition to tenure and experience, different roles can have different functions and that this too can impact a worker's time and capacity to take a vacation.

Another interesting distinction between positions comes to light when comparing 1) firm owners, defined as running a firm with at least two people, 2) solo producers operating on their own, and 3) firm employees who work within a firm owned by someone else. We find a similar pattern prevails, where the median number of hours worked by owners and employees (both 45 hours) was less than solo producers (40 hours), and the median vacation time taken each year for owners (18 days) and employees (19 days) were less than solo producers (20 days).

Which further suggests that managing personnel and office operations, which have their own complexities and may not allow as much flexibility as servicing clients, can compel a worker to work longer hours and compromise their ability to take vacation time. On the other hand, solo producers, who have a simpler operational setup than a larger business and no personnel to manage, may have more flexibility when it comes to setting their work hours and taking a vacation.

When comparing working hours and vacation time taken with the reported quality of life, the number of vacation days taken each year (and perhaps to a lesser extent, the number of hours worked per week) appears to have a direct impact on an advisor's wellbeing. Advisors reported quality-of-life scores that improved with increasing vacation days taken (ranging from 'very low' scores with 15 vacation days, to 'very high' scores with 29 days). There was a less distinct impact on quality of life by working hours, although those who reported a very high quality-of-life score reported working fewer hours per week (38–40 hours) versus advisors who reported lower scores (42–45 hours).

So what is going on that may cause these differences in wellbeing? Let's consider the two dimensions of vacation and work hours separately. When it comes to vacation, the 'very high' quality-of-life score was separated from the 'very low' quality-of-life score by 14 vacation days, indicating that two weeks of vacation can make a substantial difference in an advisor's quality of life.

When it comes to the number of work hours, the highest and lowest numbers of hours differed by about 4–7 hours per week (where the 'very high' quality-of-life median was 38 hours, and the 'very low' and 'low' quality-of-life medians were 42 and 45 hours, respectively).

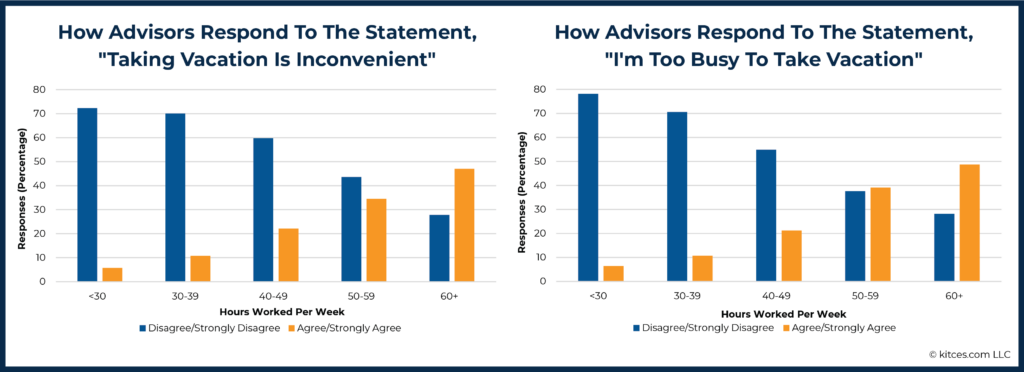

While some of these reported hours may simply reflect the social acceptance of what comprises a typical work week and how much time we should spend working every week – most people may consider working 9–5 Monday through Friday is standard practice and may not ask to work less than 40 hours a week – working more than 40 hours per week on average may be changing an advisor's mindset to believe that they are too busy to take a vacation. And that seems to be what our study found, as the more hours per week advisors worked, the more likely they were to report that they were too busy to take a vacation and that taking a vacation wasn't convenient.

Additionally, advisors who had reported working 50+ hours a week reported that when they did take a vacation, they had a tendency to check email, take phone calls, and stay connected with the office in some form. Which means that when advisors who worked longer work weeks actually did manage to take a vacation, they were doing so without fully disconnecting from the office. Conversely, advisors who reported working fewer hours were more able to disconnect when on vacation.

Which suggests that advisors who tend to work hard don't seem to be offsetting their work hours with time to 'play hard', too. Advisors who overwork to this extent do not have an opportunity to relax, and their wellbeing may suffer because of a struggle to balance work and leisure.

For advisors who are aiming to better balance their work and personal lives, the challenge may be first to understand how their work impacts their ability to take time off so that they can more effectively shift their responsibilities to accommodate more flexibility in their schedules. For example, executives who need more time off might focus on hiring support that will free up their time managing staff or the office, whereas a lead advisor might focus on finding ways to reduce their client load.

Identifying which levers to pull to shave off a few work hours each week and add a few days of vacation each year, and implementing a strategy to use their vacation time to fully disconnect from their work, can be a good start to help advisors make positive changes for their overall wellbeing.

More Revenue And Staff Don't Always Lead To More Vacation

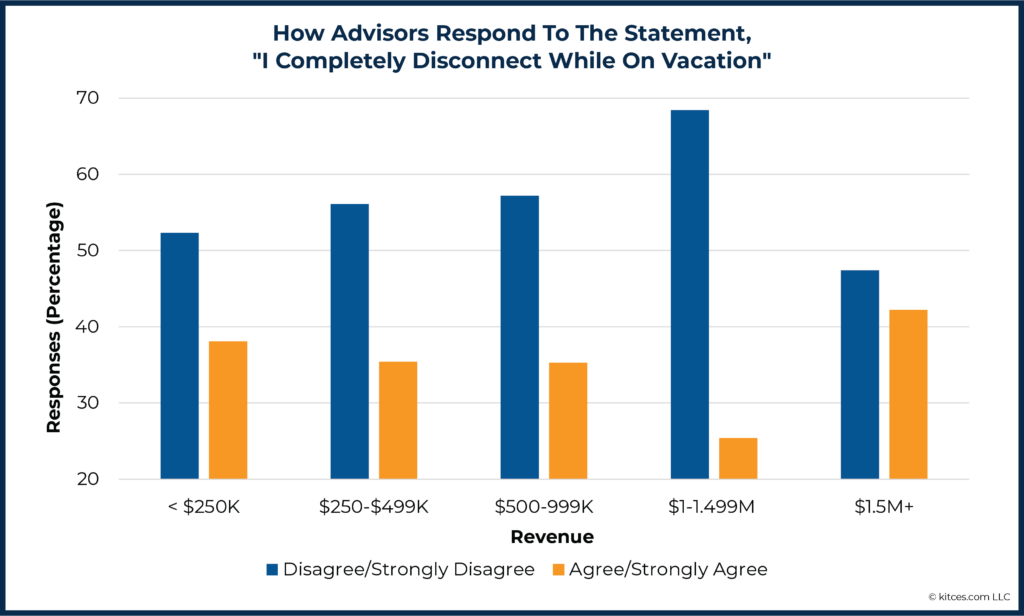

Some advisors may believe that growing their firms can be one way to reduce their weekly working hours and enjoy more vacation time. Yet, our study suggests that feeling able to disconnect from work gets more difficult as revenue goes up… up to a certain point.

Our data suggested that as revenue increased up to $1.5 million, advisors reported that it became more difficult to disconnect from work while on vacation. However, once revenue surpassed $1.5 million, advisors found it easier to disconnect from work when on vacation.

We understand that the shifting pictures of what advisors are doing (or not doing) as they grow can influence the challenges they face in balancing their work and personal lives. When firms aim to grow, advisors may become more attentive to servicing their existing clients and developing new client relationships. For smaller firms with less revenue potential, it may be difficult to delegate responsibilities, as there may be limited support available from a smaller staff. Yet when firms grow large enough to a certain size, additional support may be available where vacation and shorter work weeks become more feasible for advisors.

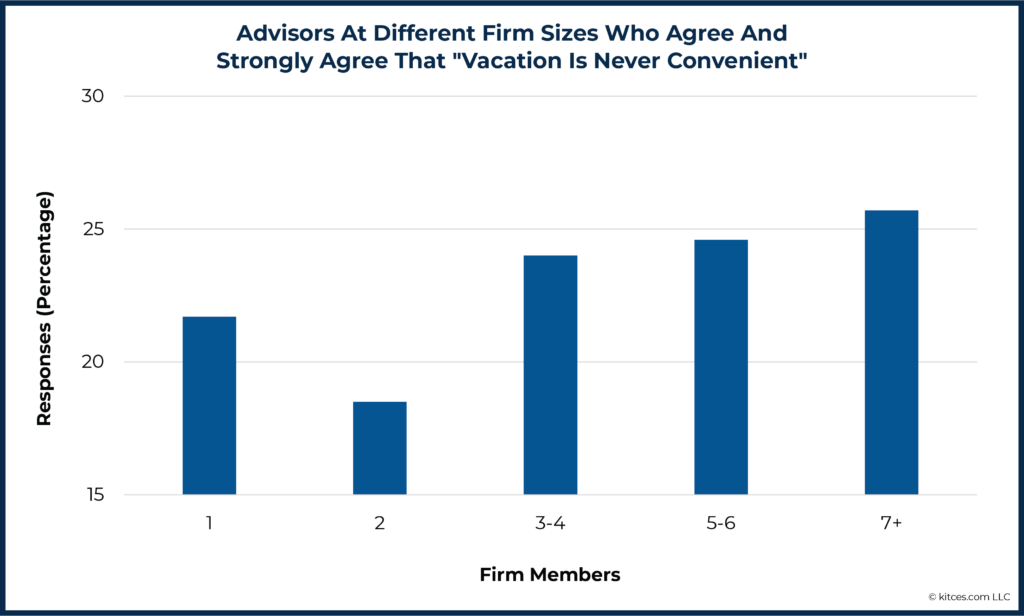

To examine whether the responsibility of managing staff compromises an advisor's ability to take a vacation and work fewer hours, we also examined how firm size impacted the advisor's beliefs about vacation. Our data suggest that as a firm increases in size (at least up to 7 members), a greater percentage of advisors agree with the statement that vacation is never convenient.

These data suggest that it may be the responsibility of managing more staff that causes advisors to feel that taking vacations is not convenient. Because having staff to manage, in and of itself, creates additional work, which can also explain why executives take less vacation than lead advisors (as shown earlier).

Set Expectations For Clients And Acknowledge Growth Goals For More Relaxation

Summer is here, and we want advisors to be able to relax and enjoy a good book (or even some Nerd's Eye View blog articles and podcasts on advisor wellbeing)! Here are a few ideas and suggestions to make it happen.

Managing Work Week Expectations

For advisors who are seeking to shorten their work week, say down from 45 hours to 40 hours, deciding on realistic working hours can help them structure their time in a way that will help them meet their goals. For example, if an advisor decides they want to stick to an 8-hour workday that goes from 8 to 5 pm, they can stop responding to emails and answering phone calls after 4 pm. This leaves them with 1 hour to close out the day before heading home.

Setting expectations for clients is especially important, too, and advisors can do so by simply including the information in their email signature:

- I answer emails and phone calls between the hours of 9 am and 4 pm. If it is after 4 pm, I will respond on the following working day.

- I raise tiny humans and do not take phone calls or emails after 4 pm.

- I practice what I preach – I preserve my own wellbeing by only responding to emails and phone calls between 9 am and 4 pm.

Using (and sticking to) this method also teaches clients, gently, that you mean it, so advisors should hold themselves to the expectations they have set, and clients will start to respect them as well.

Communicating To Clients About Vacation Absences

The key to letting clients know about vacation absences, like managing working hours, revolves around communication and setting expectations. It is 100% okay for advisors to plan a vacation and tell their clients that they will be unavailable for a few days, a full week, or whatever period the advisor will be gone. But it is essential that this be communicated to clients so that they can understand the advisor's schedule and respect their time. Here are some ways that advisors can communicate their vacation needs to clients:

- Bring it up in new-client orientation/onboarding. Advisors need to explain what happens to their practice if they get hit by a bus. In that same conversation, advisors can also explain that they are committed to their clients for 50 of the 52 available weeks in a year. And those two weeks will be spent on vacation.

- Bring it up in check-in calls: This year, the advisor is going to take a vacation. The dates are finalized, and as the time gets closer, more details will be released for emergency contact purposes.

- Bring it up in a monthly email: Use monthly or quarterly communication with clients to announce when a vacation is coming and let clients know who they need to connect with in case of an emergency.

Hiring Help To Delegate Responsibility

Now, if you can hire…do it! This is especially relevant for solo advisors who want to hire an additional advisor to join their firm, as results from our study suggested many benefits from growing a 1-person firm to a 2-person firm. For instance, advisors may feel they have more flexibility when it comes to client management and firm operations. Additionally, advisors growing from a 1-advisor to a 2-advisor firm reported having a greater sense of wellbeing, which we think can have a lot to do with the potential camaraderie involved in having at least one colleague to share work experiences, ideas, and responsibilities.

Even though adding more employees to a firm can help balance an advisor's workload, managing those employees does involve a great deal of responsibility. Which means that being aware of the commitment needed to manage staff and office operations is important, as it remains essential to continue setting client expectations. While advisors might not always be able to control the amount of work they are given, they can control how they communicate and set expectations for clients. All staff members should be encouraged to do the same.

Dedicated Management Of Firm Operations

For firms with at least 3-6 advisors, hiring a dedicated operations manager (which makes the most sense when the firm has at least 5 total staff members) can help to alleviate growth pain points involving personnel matters and overseeing office operations, which is especially important in the absence of the advisors and/or owner.

While it does take time to get to this point, if advisors are very worried about how to balance managing personnel, office operations, and client relationships, the answer is not going to be to hire another advisor. Instead, the answer will most likely be found in hiring dedicated management.

Having a healthy work-life balance is achievable; cutting the work week down by just a few hours and considering just a week or so of vacation can be a good start to improving an advisor's wellbeing. The trick is knowing what to expect and what advisors can (and can't) control with respect to their responsibilities and how their firm operates.

Perhaps most important is setting expectations, which is a good, healthy thing to do. Advisors encourage their clients to set healthy boundaries, take vacations, and set personal goals. When clients see their advisor do the same, it only further reinforces the advisor's advice!