Executive Summary

A common complaint about the use of tactical asset allocation strategies - which vary exposure to bonds, equities, and other asset classes over time - is that they are "risky" to the client's long-term success. What happens if you reduce exposure to equities and you are wrong, and the market goes up further? Are you gambling your client's long-term success?

Yet at the same time, the principles of market valuation are clear: an overvalued market eventually falls in line, and like a rubber band, the worse it's stretched, the more volatile the snapback tends to be. Which means an overvalued market that goes up just generates an even more inferior return thereafter. However, greedy clients may not always be so patient; there's a risk that the planner may get fired before valuation proves the results right.

Which raises the question: is NOT reducing equity exposure in overvalued markets about managing the CLIENT'S risk, or the PLANNER'S?

The inspiration for today's blog post comes from a series of conversations I've been having with various planners about tactical asset allocation over the past year, and the all-too-common refrain I hear about how it's "so risky" to reduce a client's equity exposure, despite the clear evidence that long-term valuation impacts long-term returns. And it's not just evidence that has arisen after the fact; Shiller's Irrational Exuberance came out in 2000, Easterling's Unexpected Returns: Understanding Secular Stock Market Cycles was out in 2005, and the Journal of Financial Planning has had several articles about the implications of a coming/ongoing decade of reduced returns, including an article by yours truly in early 2006. In fact, Shiller drew his "Irrational Exuberance" title from a speech that Alan Greenspan delivered all the way back in 1996, which implied that markets might be in a state of irrational exuberance even then.

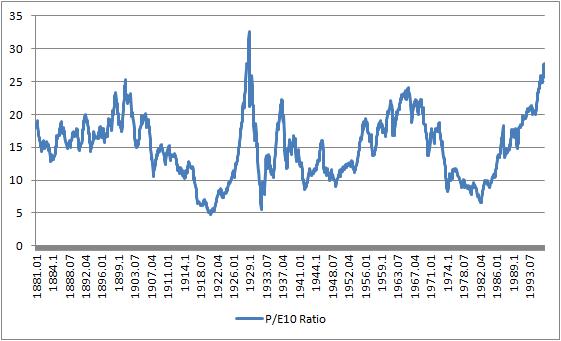

And it's not hard to see why. The graph below shows the P/E10 ratio (calculating P/E using a current price, and an average of the preceding 40 quarters {10 years} of real earnings) of the markets by late 1996 when Greenspan delivered his speech. The results are striking; the markets were as overvalued at a P/E10 ratio of nearly 28 as they had been at any time in history, except for a brief spike above those levels in the summer and fall of 1929... and we all know the consequences that occurred thereafter.

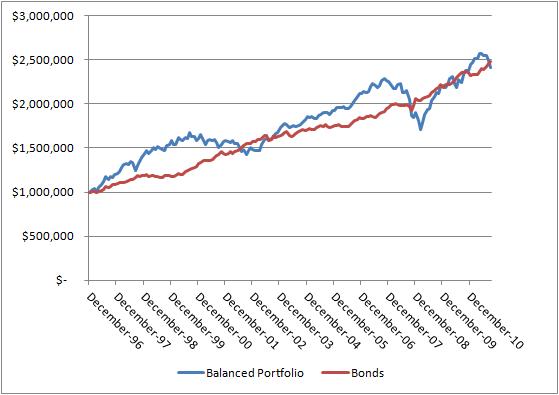

So what would have happened if you took the advice valuation was implying, and took your client's 50/50 balanced portfolio out of the stock market at the end of 1996 in response to the dizzying valuation levels and Greenspan's speech? The results are shown below, which reveal the cumulative value of a $1,000,000 client portfolio that either exited the markets completely and invested 100% into the Barclays (then Lehman) Aggregate Bond Index, versus the client who "stayed the course" in a 50/50 portfolio (which furthermore was annually rebalanced).

The volatile results are stunning. On a cumulative return basis, the balanced portfolio leapt ahead for the first few years, as the extreme market valuation at the end of 1996 only got more extreme by the end of 1997, more so after 1998, and even more so after 1999, until the bear market began in 2000. But by the bottom of the bear market in 2002, the balanced portfolio was behind... although a year or two later it was ahead again... only to fall once more in the global financial crisis in 2008, rise again with the sharp recovery since early 2009, and then dig below again as the market pulled back this summer (chart through the end of Q3 2011). On a cumulative basis for the just-shy-of-15-years period, the balanced portfolio delivered an average annual return of 6.17%; the all-bond portfolio did 6.35%. Notably, though, the latter achieved the slightly superior result with radically less risk; the all-bond portfolio had a standard deviation of only 3.59%, compared to the balanced portfolio's 8.20%. And for the record, the S&P 500 on its own had an average annual compound growth rate of 4.75% over this time period, with a standard deviation of 16.51%; so much for stocks overperforming bonds over the long run, and delivering an equity risk premium!

So on a total return basis, the balanced portfolio barely earned returns comparable to the all-bond portfolio, and got there with twice the volatility along the way. As expected (based on starting valuation), the stocks were a drag on the total return over the time horizon (with quadruple the volatility of the bonds), even after the market timing of the rebalancing trades added a little over 50 basis points of return. And it's even worse when examined on a fully risk-adjusted basis; in late 1996, the 15-year risk-free rate (a 15-year U.S. government bond) was yielding over 6.50%, higher than the return of the S&P 500, the Barclays aggregate bond index, or the 50/50 (re-)balanced portfolio, which means the Sharpe ratio is negative for all three portfolio options!

In other words, up front the valuation data indicated that the equity returns would be quite inferior to their historical norms (and the risk-free rate!) 15+ years later, and the actual results firmly support the up front prediction. And as the markets rose, the numbers only got worse: the end-of-1997 client earned only 5.13%/year in the balanced portfolio compared to 6.12% in the bond portfolio; the end-of-1998 client earned only 4.14% to the bond portfolio's 5.92%; and the end-of-1999 client earned only 3.65%/year through the end of September 2011, compared to 7.14% for the bond portfolio (and -0.43%/year compounded for the S&P 500 itself!). If this comparison had started at the end of 1999, the all-bond portfolio would be beating the balanced portfolio by hundreds of thousands of dollars and a 30%+ cumulative return!

So if the planner was truly investing for the client's long-term financial success, the clear valuation metrics indicate it would have been a good idea to get out of the way of the markets by late 1996 when Greenspan suggested there might be some irrational exuberance out there, and it turns out the advice was accurate and true. If the planner and client didn't get out of the markets in late 1996, the signals were only stronger (and the subsequent returns even more inferior) for every year waited, reinforcing the ramifications of valuation.

So far, so good. There's just one problem: the planner who executed this evidence-based, data-driven, non-subjective, client-centric investment strategy would probably be out of business today. Let's look at how it would have gone in real time:

- 1997 goes by. The bond portfolio is up a whopping 9.7% (oh, to earn 9.7%/year in an all-bond portfolio today!), but the balanced portfolio would have been up 21.5%, on the back of a 33.4% stock return. Your 10% greediest clients can't take it and leave.

- 1998 goes by. The bond portfolio is up another 8.7%, but equities are up another 28.6% and the balanced portfolio would have been up 18.6%. Another 20% of your greedier clients leave; you're starting to sound nuts about this valuation thing.

- 1999 goes by. Greenspan started raising rates and spooked the bond markets; the aggregate bond index is DOWN almost 1%, while the S&P 500 is up another 21% and the balanced portfolio is up over 10%. Another 25% of your clients leave; you just don't understand the new economy.

- 2000 arrives, and the bear market begins. Your bond portfolio rallies over 11% that year, and over 30% through the end of 2002, while equities fall near 40% and even your balanced portfolio loses money. You are vindicated... at least in the eyes of the 50% of your clients who have stayed. You pick up a few new clients who think you "called it" (not realizing you had been defensive for years).

- With the bear market over, the market rallies hard in 2003, rising 28.7%, which your bond portfolio is up only 4.1% in the face of ultra low yields. It doesn't get much better over the next few years, as Greenspan raises rates through 2005 and 2006, increasing yields but taking a bite out of your returns due to the associated price declines in your bond prices. By the end of 2007, no one remembers the bullet you dodge in 2000-2002; they just see that equity markets are up over 80% while the bond portfolio is up 24%. Lots of clients are leaving again. You got it right once, but now you're out of touch!

- As markets have been overvalued all along, your perseverance pays off again; the global financial crisis hits, and the S&P 500 is off 37% in the calendar year, dragging the balanced portfolio down almost 16%, while your bond portfolio is up 5.2% on the back of dramatic rate cuts. Score another one for valuation.

- Unfortunately, the sharp decline is followed by a sharp recovery. Two years later, by the end of 2010, the markets have bounced 45% from December 31, 2008, while the bond portfolio has merely chugged out a 12.8% cumulative return for two years. Clients are doubting (i.e., leaving) again.

- A pullback in the summer of 2011 raises the specter of success again; through Q3 of 2011, the S&P 500 declines 8.7%, dragging the balanced portfolio negative, while the aggregate bond index is up 6.6%. Maybe valuation still matters, but clients are still skeptical.

The above story is a daunting picture, and highlights the true risk of being tactical: it's not the client's welfare that is on the line, but the planner's! Clients' (and all investors') memories are short; in the strong bullish years, some leave for greed and better returns, and while the successes in the bear years help, a lot, clients forget about the successes after another string of bull market returns and start leaving again. Whether you're selling investments for a commission, managing assets on a fee basis, or just giving clients hourly advice, the business hazard is the same: clients who feel your advice isn't getting them to their goals in the short term may leave before you are proven right in the long term, even though your long-term advice for their long-term planning need really WAS factually accurate and correct! In theory, the only time you wouldn't honor the advice is when you, as the planner, are trying to time good short-term performance, even if it ignores the long-term ramifications of taking investment risk when you shouldn't!

So here's a little thought experiment: If you could time travel from today back to the end of 1996, knowing 100% of what the future really would hold, and were presented with a one-time decision to irrevocably keep your clients invested in a rebalanced 50/50 portfolio, or to take clients all to bonds, which would you do? Which would be the advice that delivers genuinely superior absolute and risk-adjusted returns for your clients? Which would be the better advice for your viability of your business? What do you do when the answer for the client is different than the answer for your business? And when we say it would have been "risky" to not be in stocks for the past 15 years, whose risk are we really talking about?

This is a super article, Michael.

I agree with the suggestion that the only significant risk in following valuation-informed strategies is to the planner, not to the investor. The only problem I have with this suggestion is that it comes off as bit cynical (I understand that that’s not your intent, I just mean that some will hear it that way). I think it may help to put these realities in some context by providing some historical perspective.

Stock investing was not a subject of academic study prior to the 1960s. So we are still very much in the pioneer days when it comes to figuring this stuff out. Fama and those who followed his path have put forward some amazing insights of true and lasting value. So, when Shiller pointed out the flaws, it was hard for people to reexamine conclusions they had come to believe with great confidence.

If Shiller’s model were a mere adjustment to Fama’s model, there would be no problem. Everyone would want to move forward by adding the Shiller insights to the Fama insights. The problem is that Shiller’s model leads to OPPOSITE conclusions on just about every point. That’s what has made the transition from the Fama model to the Shiller model so contentious and difficult.

I was driving to Philadelphia one time on I-95 and I had a lot of things on my mind and I took the South exit rather than the North exit. I drove three hours in the wrong direction before I realized my error. For a few minutes I tried to tell myself that I had not done what I had done. Accepting that I was going to need to drive three hours just to get back to where I started was unbearable.

That is what is going on here. When as a society we reach a point where we are able to accept that all the investing experts have been driving in the wrong direction for 30 years, we are going to be able to provide people with the best investing advice that has ever been available. Taking advantage of Shiller’s research lets us reduce the risk of stock investing by 80 percent. The hard part is accepting that we got it so wrong in our first-draft effort at developing a research-based model.

My point here is that our problem is not that people are dumb or bad. It is that people are human and make mistakes. The hardest mistakes to acknowledge are the ones that do the most damage. And investing is so important to so many people that mistakes made in this field cause an awful lot of damage. We had no idea how dangerous a road we were walking when we began the project of using academic research to learn how stock investing really works.

Rob

In my firm, client’s take a risk tolerance test. This is one of the primary inputs to determining an appropriate asset allocation for the client. Even if the client’s time horizon and other life circumstances argue for, say, 80% equities/20% fixed income, if they’re really conservative, then we’ll put them in a more conservative portfolio, somewhere more aggressive than what they want and less aggressive than what is suggested by other factors.

I don’t believe this is a controversial move. If we put them in something as aggressive as what we wanted, they’d give up investing and do the wrong thing at just the wrong time because they couldn’t handle it psychologically (the ol’ “go to cash in March 2009”).

We all agree that’s undesirable from the client’s perspective. But isn’t this just the psychological flipside to the scenario you present here? If the advisor were to insist on keeping the client in a (supposedly) overly *conservative* portfolio, as you describe, then yes the client might leave and therefore hurt the advisor’s business. But it also means the client might very well go too far in the *other* direction. Instead of the 50/50 portfolio you might have been able to sell the investor on, he’ll veer way too aggressive at just the wrong time and be hurt worse than he would have been in a 50/50.

Isn’t bending to/accommodating your client’s psychology just as important in good times as in bad?

Very interesting, but I think my interest and the client’s interest are closer than this post leads one to believe.

Which clients of mine’s best interest am I helping if I know that a significant portion of them are going to abandon me and the original plan, only to lock in far inferior results?

Do I have my client’s best interest in mind if I know 55% of them (based on your example above) are going to leave me by the end of the 3rd year? In doing so, they would have had steady, low returns, those first few years and now be moving to another advisor that will investment them more aggressively at precisely the wrong time. Seems like the start of a very vicious cycle of buying high and selling low that would be facilitated by jumping from advisor to advisor. This would surely mean that a good portion of my original client base would end the fourteen year period with far worse results that all outcomes mentioned in your post.

To me, the actions that support the best interests of the clients are the ones that have them stick with either plan for the full fourteen years.

Michael,

Yes there are times when it is technically in the client’s best interest to be fully in or out of the stock market (due to valuations, time horizon, etc). But if they can’t stick with it because of volatility or envy/regret you have a problem.

While we have pretty good tools at this point for measuring a client’s downside tolerance, this demonstrates we need a way to measure how much tolerance a client has for their returns to underperform their peers for a period of time.

And if that tolerance for underperformance is low that needs to be incorporated into their allocation just like a low volatility tolerance would be.

David

David,

Thanks for sharing.

It’s an intriguing thought to consider whether/how we might measure a client’s tolerance for underperformance to the upside.

Anecdotally, my impression is that we as advisers may tend to rank this higher than at least some (although definitely not all) of our clients… in part, perhaps, because of the implicit business concerns noted here.

It’s an interesting thought, though, and would certainly enrich some client dialogues.

– Michael

This is interesting, but, I think, mostly sophistry.

What was the client’s asset allocation before this 15 year period and what is the full time horizon, including the period before and after?

And you can’t forget that this was in the middle of a raging bond bull market. If the client’s goals could be surely met with a 6.5% return for the 15 year period, then sure it would have been a good move. But then what, assuming the actual time horizon is another 15-20 years?

And what about other asset classes that may have been in the portfolio, small cap and value and international, etc.? I believe a more fully diversified portfolio does better for the period. Especially the tech bubble.

But the main point is this: We (the advisor and the client) are trying together to do an impossible job – just well enough. Achieving the best returns possible is not the goal. Nor is achieving the highest Sharpe ratio. Most importantly, you can’t isolate the the client’s interest and the planners interest as clearly as you have. (If being so smart and so right puts you out of business because so many clients leave under your scenario, the clients won’t have you to get them back in.)We’re embraced together in a dance, neither of whom knows all the steps.

Steve,

The point is what to do with THIS 15-year period. Does it really matter what the asset allocation was before or after? Surely the client can change allocations once every 15 years?

I am not assuming the client’s goals could be met with a 6.5% return. Assuming they could NOT, and absolutely required a 10% return. If that was the case, the answer is still NOT to own the 50/50 portfolio! The real answer is that the client has unrealistic goals given the impending low return environment, and needs to change to goals that don’t require an impossible-to-achieve return. If the actual time horizon was 30 years, it STILL doesn’t make sense to deliberately own high-volatility low-return assets for the first 15 years; if the time horizon is longer, own bonds the first 15 years, and re-evaluate later (as valuation levels DO change over time, as secular market cycles clearly show).

The fact that including other asset classes in the portfolio may have done better is a moot point. The point is that including large cap stocks (since that’s the index we’re using here as an example) was bad. Pick any portfolio you want, including small cap and value and international. That portfolio still does BETTER when it’s small cap, value, international, and NOT overvalued large cap US stocks for the next 15 years. (Yes, strictly speaking, you could look to valuation for each of those separately to decide which asset classes to include.)

The point remains that any client who had the time horizon, risk tolerance, and goal needs to earn large cap equity returns was still better served to NOT own large cap equities, because of the excessive valuation that has predicted with 100% accuracy(!) that subsequent 15-year equity returns will be materially below long-term averages (including this time period).

This isn’t about receiving the best possible returns. The best possible returns would have involved active trading throughout this time period. This is actually about the opposite – if you’re NOT going to try to generate short-term marketing timing trades and just invest for the long-run, there are time periods where stocks are a terrible addition to that portfolio. Yet inexplicably, we as planners STILL tend to suggest that it’s “risky” to not-own stocks, when in reality the only material risk is to our business and ability to keep clients, NOT to the client’s goal.

Or in your terms – the steps are actually far more known than you imply. We seem to have a strong tendency to deliberately ignore the guidance available about the steps, perhaps because we don’t want to deal with the business ramifications of knowing?

Respectfully,

– Michael

Michael,

To answer your question: Even in retrospect, I would prefer the 50/50 strategy, with it’s slightly lower returns and higher, yet manageable, volatility.

As an investor (let alone as an advisor) I prefer a strategic strategy that’s easy to implement to a tactical strategy that’s hard to implement. The tactical strategy is hard to implement because it requires constant evaluation and decision making, which may get thrown off track for a variety of reasons, mostly, as you point out, behavioral reasons.

For the record, DFA’s 60/40 (36% US, 19% International, 5% Emerging, 40% Fixed)Balanced Strategy, for the 15 years from 1996-2010 returned an average annual 8.3%. My guess is that Israelson’s 7/12 would have similar results.

Steve,

It’s worth noting that I’m not saying everyone “must” be tactical. You can make a conscious decision for strategic. The point (of this post at least) is simply that we need to STOP saying tactical strategies like this are “risky for the client” because they’re not. They’re risky for our business. If we’d rather make a business decision to implement another strategy, that’s at least a separate conversation.

It’s worth noting, though, that the differences are not always as benign as the example I’ve given here since 1996. If you made the tactical change in 2000, your $1,000,000 balanced portfolio grew to $1.5M, and your bond portfolio grew to $2.1M by the end of Q3 this September (and again, the bond portfolio had less than half the volatility). The tactical investor has 35% more than the strategic rebalancer, after more than a decade. That’s a gargantuan, highly material difference for most clients’ financial plans. It’s an even more extreme 10-year difference if I measure from the last two times the P/E10 rose above 25. In other words, part of what’s unique about 1996 is that, by historical standards, that was actually the BEST outcome we’ve ever seen from such P/E levels… because the bubble went so high, and took so long to pop. But that’s not something I’d really want to count on systematically. 🙂

As for DFA’s portfolio, I still don’t see your point. Run the same portfolio without Large Cap US, and the returns are even higher. It’s still true that these stocks were excessively risky and priced for low returns. And notably, small caps were at historically LOW price extremes (that’s what you get for being unfavored in a bubble!), which means the incredible small cap performance in the early 2000s was just as predictable as the horrendous performance for large cap. So if you adopted these strategies across asset classes, make your 36% US into something that was 100% small cap and 0% large cap, and see how much higher your return would have been! Valuation still matters; any diversified portfolio you construct still would have been improved by underweighting the extreme high valuations and overweighting the extreme low valuations.

Respectfully,

– Michael

I thought it might be interesting to take a page from the David Loeper handbook (people can’t eat risk-adjusted returns) and take the growth of $1,000,000 chart a step further by introducing annual withdrawals of $40,000 each year.

Through September, 2011, the 50/50 portfolio ended with a higher cash value: $1,600,185 for the all bond portfolio, and $1,643,639 for the 50/50 portfoio.

Ultimately, though, that gets away from the point of your post. There’s an interesting effect going on there for people who have the courage of their convictions in maintaining over/undervaluation calls. It’s similar, in some ways, to the hedge fund managers in Michael Lewis’ “The Big Short”, where one manager started seeing redemptions before his correct call on the housing market started paying off.

Ultimately, I think David hit it right on the head. If your client starts looking around and wondering why he/she isn’t making money – or at least as much money as everyone around them – then you have a problem, no matter how correct your valuation hypothesis turns out.

Michael,

per a certain ‘personal finance guru’, you could also simply invest at any time into 100% good growth funds and make 12% annual returns. It’s so easy to pick these funds because you can just look at their 10 yr track record which is the most accurate predictor of future returns.

I apologize for the sarcasm. I felt like the conversation could benefit from some comic relief. 🙂

Years ago a planner friend of mine referred to financial planning as “Applied Dismal Science” – and that was during the 90s! Clients always wanted more than they could reasonably expect. Now the stock market is over-valued, the bond market is over-valued and maybe the 4% “rule” should be more like 2%. What’s a planner to do? When I tell clients how much they need to save I doubt we’ll even get to talking about how to invest it.

Michael,

what are your thoughts on the following perspective regarding the PE10? http://advisorperspectives.com/commentaries/edmp_101211.php