Executive Summary

Welcome to the December 2025 issue of the Latest News in Financial #AdvisorTech – where we look at the big news, announcements, and underlying trends and developments that are emerging in the world of technology solutions for financial advisors!

This month's edition kicks off with the news that the estate planning software provider Vanilla has launched a new "Starter" subscription tier, which provides estate documents and basic estate planning tools without the sophisticated planning capabilities of Vanilla's core product – which may be an acknowledgement of the reality that the types of clients whose needs are served by technology-driven estate document creation are usually those in less complex situations that don't require high-end planning capabilities, so it makes sense to unbundle document creation from planning so that those who just need documents can get them without having to buy the entire software package.

From there, the latest highlights also feature a number of other interesting advisor technology announcements, including:

- FP Alpha has launched a new "NextGen Tax Insights" tool, which analyzes a client's tax return and other financial data and identifies planning opportunities, which come from a predetermined list of strategies created and vetted by tax and financial planners – offering a potential model for how more planning tools could incorporate AI that doesn't generate new planning ideas from scratch but instead simply expedites the process of analyzing data and brainstorming ideas (with the advisor still being in charge of the final recommendation)

- A new AI-driven prospecting tool called WealthReach uses "de-anonymized" data from visitors to an advisory firm's website to identify prospects who may be interested in the advisor but didn't book a meeting – although the main problem for advisors isn't usually that they're getting too many visitors who don't book a meeting, but that they don't get enough visitors to their website to begin with, which means that it might make more sense to invest in a better marketing strategy that can bring in visitors before using a tool like WealthReach

- A recent influx of investments by advisor platforms into alternative investment-related technology suggests that more advisors are adopting alternatives, making it worthwhile for platforms to build out their alternatives infrastructure (because even if alternatives make up only a small percentage of overall AUM, the basis point fees on even a fraction of that amount could generate a healthy return on the investment)

Read the analysis about these announcements in this month's column, and a discussion of more trends in advisor technology, including:

- Why Altruist's announcement that its Hazel AI notetaker will start to pull in client custodial data from Altruist raises the question of when AI notetakers will start to usurp CRM software's traditional role as an interface between advisors and client data – and if CRM systems will even be needed if AI is able to weave together client data from all sources without needing to store it in a centralized spot?

- In light of the news that pre-AI meeting transcription service Mobile Assistant reportedly considered (but ultimately turned down) an offer to sell its meeting transcript data to other vendors for AI training purposes, it's worth it for advisors to ask their technology vendors what they can and cannot do with their clients' data, since the data privacy issues that advisors might have considered years ago when they signed their vendor agreement might be completely different in today's AI-dominated landscape

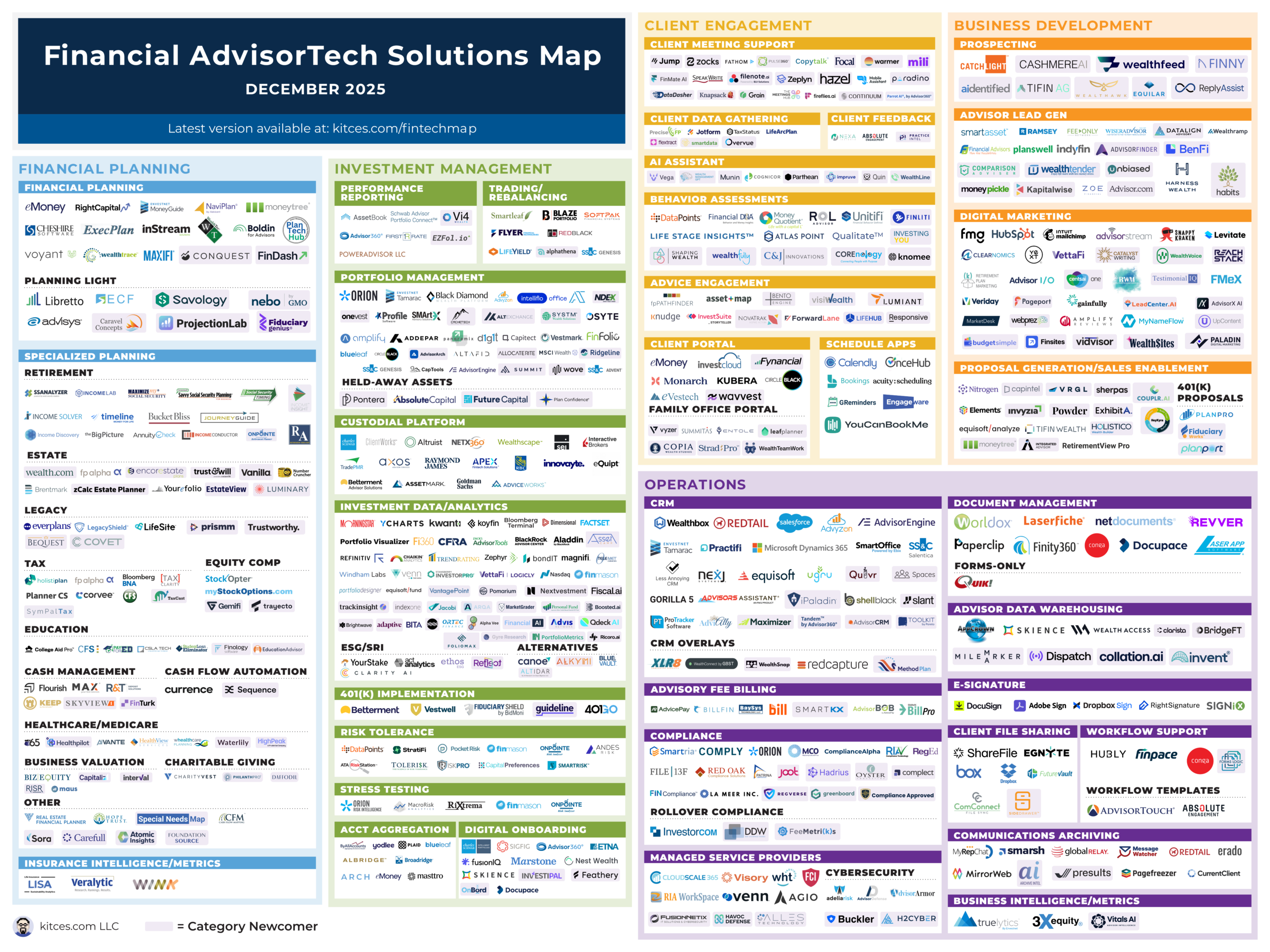

And be certain to read to the end, where we have provided an update to our popular "Financial AdvisorTech Solutions Map" (and also added the changes to our AdvisorTech Directory) as well!

*To submit a request for inclusion or updates on the Financial Advisor FinTech Solutions Map and AdvisorTech Directory, please share information on the solution at the AdvisorTech Map submission form.

Vanilla Launches "Starter" Tier For Clients Who Just Need Estate Documents (But Not Complex Planning Software)

Working with clients on estate planning has two basic phases. First there's the actual planning part: determining where the client wants their assets to go if they pass away, what sort of protections they want to put in place (e.g., ensuring that a child's inheritance doesn't end up with an ex-spouse if they get a divorce), and who they'd like to name as executors, trustees, and/or guardians. Then after planning, there's the implementation phase, where the estate documents are drafted and signed, beneficiary designation forms are filled out, and assets are re-titled to ensure that the client's wishes will be carried out.

Likewise, the technology to assist advisors with estate planning is also largely bifurcated into planning- and implementation-focused tools. Providers like FP Alpha's Estate Module, Yourefolio, and Luminary offer tools to help visualize clients' estate situations, build projections and what-if scenarios, and model recommended changes, but don't create the documents themselves. Others like Trust & Will and EncorEstate Plans are primarily focused on implementation, facilitating the creation of estate documents but having more limited planning capabilities. And a third category, including providers like Vanilla and Wealth.com, combines both approaches, packaging together full-featured planning software and document creation into a single subscription.

For clients with less complex estate situations, what's often important is getting estate planning documents that meet the client's basic needs (e.g., guardianship, distribution of assets that don't pass by beneficiary designation or deed, and appointment of a power of attorney and healthcare proxy). With most human attorneys charging multiple thousands of dollars even for basic will-based documents, technology that can do the same thing for a few hundred dollars can remove much of the friction from the process of estate document preparation and help advisors ensure that their clients get the essential documents they need in place. And so the more implementation-focused tools like Trust & Will and EncorEstate Plans are often a good fit for advisors who just need to help their clients without overly complex planning situations the documents they need.

But when client situations get more complex, the need shifts to the planning side. Software that can help to visualize and model different planning scenarios and trust types can make it much easier for clients to grasp their available options and decide on a strategy that works for them. But when it comes to drafting the documents themselves, the complexity and specificity of the client's needs means that it's still often necessary to have a human attorney draft the documents. Because although the attorney-drafted plan may be much more expensive than one created by technology, at a certain level of wealth and complexity the cost of the plan becomes less of a factor compared to the necessity of getting everything right. And so planning-only tools like FP Alpha, Yourefolio, and Luminary help fill the need for advisors who want to assist on the planning side, but leave implementation to a human attorney.

But for Vanilla and Wealth.com, which bundle together estate planning and document creation, the product-market fit isn't as clear. The clients who are most likely to benefit from technology-driven estate document generation (i.e., less complex clients) don't usually need sophisticated planning tools. And those that need the planning tools (i.e., more complex clients) are more likely to want to work with a human attorney to draft their documents than to trust technology to do the job. Combining both planning tools and document creation into a single offering means that advisors who intend to use it primarily for one purpose or the other still need to buy the whole package, even if they only use half of it. Which may be a big reason that, in our most recent Kitces Research on Advisor Technology, multipurpose providers like Vanilla and Wealth.com scored materially lower in satisfaction than more focused tools for planning (FP Alpha) and document creation (Trust & Will and EncoreEstate Plans): Because users aren't likely to very happy with a product that they're using only part of when they're still forced to pay for the whole thing!

In this context, it's notable that Vanilla has recently launched a new "Vanilla Starter" subscription tier aimed at providing estate documents plus a basic layer of "essential" estate planning technology for clients with less complex estate planning needs.

Up until now, Vanilla's focus had been on sophisticated estate planning technology that catered to advisors with high-net-worth clients, building off of founder Steve Lockshin's experience as an advisor working with UHNW clients. But at the same time, its core software package also includes estate document creation that is mainly technology-driven: While clients can consult with an attorney in Vanilla's professional network after their documents are created, the documents themselves are largely based on pre-made templates and populated by questionnaires filled in by the client. Which made for somewhat of an awkward fit, since automated estate document creation isn't often well suited for the types of clients needing high-end estate planning in the first place.

By separating out estate document creation as effectively a standalone offering, Vanilla is catering towards the types of less-complex clients who have a need estate documents but not for high-end planning software. In doing so, Vanilla is directly competing with the likes of Trust & Will, which similarly pins most of its value on document generation combined with "just the basics" planning capabilities. Notably, Vanilla has opted to price its service as a subscription model, charging $99-$199 per month based on the number of clients served, compared to Trust & Will's and EncoreEstate Plans' per-plan pricing. Time will tell if advisors will be willing to pay an ongoing fee for estate document creation when most clients will need to update their estate plans at most once every 10-15 years.

Ultimately, though, Vanilla seems to have grasped that there's a limit to the potential market for high-end estate planning software (since only so many clients have complex needs suited to sophisticated planning software to begin with), while advisors won't necessarily flock to Vanilla's core product to create documents for their mass-affluent clients if they aren't planning to use the accompanying planning tools. But there are plenty of mass-affluent clients who do need estate documents, and as the relative success of Trust & Will has shown, many of them are willing to trust technology to deliver basic documents at a lower cost than a human attorney. And so it makes sense for Vanilla to essentially unbundle document creation from planning tools, so that those who need documents alone can buy just the documents, while those who need more complex planning capabilities can buy the whole package.

FP Alpha Launches 'NextGen' Tax Insights Tool To Identify Planning Strategies From Client Tax Return Data

It's been almost exactly three years since the launch of ChatGPT kicked off the current era of AI-driven technology. In that time, many different AI tools have arisen to fulfill various use cases for advisory firms, from client meeting notes and email drafting to marketing content to prospecting to integrating and standardizing data from other technology tools. But the one area that has been largely untouched by AI so far has been advice itself. While advisors have been happy to employ AI as a "calculator for words" or as a chatbot interface to query data from various sources, there's been more ambivalence about entrusting AI to generate planning recommendations: Not only because of the potential for giving flawed or biased advice due to incomplete data or even hallucinations on the part of the AI technology, but also due to advisors being wary about diminishing their own value proposition by substituting their own expertise for that of an AI model.

In both cases, advisors' trepidation about AI-generated advice stems from the idea of an AI tool producing its own original recommendations. As an oversimplified example, imagine that an advisor plugs in all of their client's goals, income, and assets into an AI tool, and the AI runs everything through a black box and puts out a plan on the other side. In this scenario, while there may be AI-generated recommendations, there's no rationale for the advisor as to why those recommendations are in the client's best interests, which in turn makes them impossible to recommend as a fiduciary. And if all that comes out of the AI tool is a set of recommendations, with no explanation or rationale given for why those recommendations were chosen, then there's nothing to indicate that anything in the plan is even correct from a technical perspective, e.g., whether any tax strategies spun off by the AI are even allowed under the tax code.

But while there are obvious issues with allowing AI to generate recommendations from whole cloth, that isn't the only way that AI can be incorporated into financial advice. Imagine instead that the AI model's output was limited to a pre-defined "menu" of financial planning strategies, vetted and described in detail by human experts, and that that the AI's role was simply to look at the client data in the system and match it to the most appropriate strategy or strategies on the menu. In that case, there's certainty that any proposed strategies are legitimate – since they were put into the model by humans to begin with – and the AI can be designed to explain its rationale in recommending one strategy ahead of any others.

That's essentially the idea behind FP Alpha's recently released NextGen Tax Insights feature, which is integrated into its tax planning module. In a nutshell, the new feature takes client data – based either on information from the client's uploaded income tax return or on supplemental user-entered information like account balances and beneficiary designations – and generates personalized tax planning recommendations based off of that information. However, the recommendations themselves aren't created by the AI on its own; rather, they come from a list of curated strategies developed by tax and financial planning professionals. The AI's role is simply to analyze the client data and match it to strategies on the list that are relevant to the client and appropriate to their situation, and to give the reasoning behind each recommendation it gives.

In that way, FP Alpha's new tool isn't likely going to identify any complex new strategies that the advisor has never heard of – in fact, it's likely that most of the strategies surfaced by FP Alpha would already be familiar to most advisors (e.g., backdoor Roth IRAs, 1031 exchanges, S corporation elections, and other common planning strategies). Most advisors might have even identified the same strategies on their own after reviewing all of the client's data themselves. But the AI tool can potentially expedite the process of analyzing data and brainstorming possible solutions, quickly identifying tax planning opportunities that a human advisor might have needed to sift through large amounts of client information to get to, while also flagging any potential tax traps or implementation hurdles (for instance, noting when a client has other pre-tax IRAs that could cause the conversion of a backdoor Roth contribution to be partially taxable).

But the most significant feature of FP Alpha's approach is that it avoids the diminishment of the advisor's value proposition that a purely AI-generated plan might incur. Rather than using AI to fully automate the planning process, it really just expedites the steps of pulling together the raw client data into a list of potential strategies, which the advisor still needs to compare individually and ultimately decide which to recommend to the client. In other words, the advisor still has an opportunity to use their judgment and expertise in developing recommendations; the AI simply assists in narrowing down the universe of options to choose from.

Ultimately, FP Alpha's new tool could be an indication of how other types of planning software providers might look to incorporate AI into their own tools. Financial planning software has been notably slow to integrate AI, other than newer AI-native tools like Conquest and fast-moving startups like Income Lab. But it with AI integration into planning tools seeming more and more inevitable, it's likely we'll also see platforms like eMoney and RightCapital launch their own AI-driven features. If and when that happens, it's very possible that FP Alpha's new tool will be a model for merging AI with advice: Not as a generator of entirely new financial planning ideas, but as a faster way to narrow down the list of options (while the advisor still takes the lead in making recommendations to the client).

WealthReach Launches An AI Prospecting Tool To Help Identify And Contact Website Visitors, But How Many Advisors Have Enough Traffic To Convert?

Outbound prospecting (e.g., cold-calling contacts in the hopes that some will be willing to meet with the advisor) is largely disliked by financial advisors, with the most recent Kitces Research on Advisor Marketing showing it as one of the least utilized and lowest ranked marketing tactics available. In large part, this owes to the high amount of rejection – and the sheer amount of time needed – to get to a single "yes" on a list of names of people who may not even be interested in talking to a financial advisor. Although most advisors need to do some amount of cold calling or other cold prospecting when building a book of business from scratch, the majority of advisors seek to get as quickly as possible to the point where they no longer need to do outbound prospecting, and can instead rely on inbound prospects and existing client referrals to fill up their sales pipeline without the need to pick up the phone.

In the age of AI and big data, however, outbound prospecting has drawn a great deal of attention from startups and their venture capital funders in relation to its actual amount of use among financial advisors. In the past year or so, startups including Cashmere, Wealthfeed, FINNY, Aidentified, Wealthawk, and ExecAtlas have crowded into the Prospecting category of the Kitces AdvisorTech Map, all of which use AI to research prospects and find those with the best potential fit for the advisor (e.g., by monitoring public data sources for "money-in-motion" events like business sales, IPOs, divorces, and retirements of corporate executives). They've also brought in millions of dollars of venture capital, including Wealthfeed raising $2 million in 2024 and then landing an additional minority investment from Broadridge earlier this year, FINNY raising $4.3 million in December 2024, and AIdentified raising $12.5 million in June 2024.

The argument in favor of these tools seems to be that with RIAs on average struggling to achieve organic growth rates beyond the high single digits (and most achieving only low-to-mid single digit organic growth), advisors will flock to solutions that make it easier for them to identify the best qualified prospects. And that with inbound lead generation services like SmartAsset receiving mixed reviews (due, again, to the very high rejection rate of prospects), and a long waiting list for firms to enroll in custodial referral programs like Schwab's, there could be a significant business opportunity for technology-enabled solutions for researching and targeting specific prospects that can drive higher close rates with better matching and bring down client acquisition costs for advisors who use it.

Thus, despite the proliferation of AI-powered prospecting solutions that have come to market over the past year, there are yet still more being rolled out. The latest of these is WealthReach, which was just launched this month by the founders of WealthLine, an AI phone answering service for financial advisors.

WealthReach works by pulling in information about individuals who visit an advisor's website, or who search for certain key terms such as "wealth management", "tax planning", and "401(k) rollover". It does this via tracking cookies that capture information on website users and track their internet behavior. And while tracking cookie data is theoretically anonymous, big data and AI tools like WealthReach can match up the anonymized data with identifying information such as social media profiles, which can be further linked to publicly information like phone numbers and email addresses – effectively "de-anonymizing" the data and linking website users to their social media profiles, contact information, work history, income and more. And although the amount of information that AI tools can pinpoint about individual website users is frankly unsettling, it's completely legal – and thus can be used by providers like WealthReach to provide financial advisors with information on who is already visiting their websites and researching them or their services. The result for the advisor is a list of "warm" ostensibly-already-interested prospects to target with personalized outreach (which Wealthreach also helps to generate).

What's notable, though, is that in order to get the most out of a tool like WealthReach that can identify and provide contact information for visitors to an advisor's website, the advisor needs to have a steady flow of visitors to their website to begin with. And that in turn means having a healthy marketing apparatus that brings prospects to the top of the sales funnel by driving traffic to the advisor's website… which often is the main issue for advisors to begin with. In other words, it isn't that advisors have trouble converting some percentage of the stream of visitors to their website into paying clients, it's that they can't bring visitors to their website and scale their inbound traffic in the first place!

Furthermore, since WealthReach by definition filters for individuals who visit the advisor's website but don't reach out or book a meeting, there's a possibility that many of those people have already decided that the advisor wasn't a good fit for them and moved on. Which means that in many cases, the advisor would simply be wasting their time in trying to re-engage with visitors who had already self-selected away. There would need to be a way to filter out the bad-fit prospects from those that are still warm but just need a nudge or two in the right direction. Yet a good advisor website that can clearly define the advisor's value proposition and which types of clients they work with most will ideally do this job without needing an AI tool to discern the bad-fit prospects from the good.

Still, for advisory firms that do have a high volume of web traffic, it takes only a handful of high-quality prospects from what might be thousands (or tens or hundreds of thousands) of website visitors to quickly build a highly qualified prospect list of people who might be genuinely interested in the advisory firm and simply need a little more help and engagement to move forward in the sales process. Which means WealthReach is an interesting potential component for an advisory firm's scaled marketing effort to further amplify the results of its inbound web traffic.

The broader perspective, however, is that outside of brand-new firms and a small base of hardcore prospectors, high-volume traffic websites and prospective outbound prospecting still represents a relatively tiny percentage of advisors. While tools that can make that process more efficient by increasing the ratio of yesses to nos could in theory entice more advisors to give prospecting another shot, the current addressable market for prospecting tools still may be too small compared to the number of startups and venture capital pouring into the space, and would require a significant expansion of prospecting adoption to work in the current landscape (and even then, as in most AdvisorTech categories, 2-3 market leaders are likely to capture the vast majority of market share, making it difficult for the rest to gain traction).

The key point, though, is simply that when tools like WealthReach require a solid marketing funnel to bring users to the advisor's website for them to prospect to in the first place, few are able to fully leverage a solution like WealthReach in the first place. And amongst those who can, even those advisors might just decide it's better to invest in marketing tools that can draw in prospects who are already affirmatively interested in the advisor (e.g., by better increasing the conversion funnels of the existing website), rather than spending time and dollars chasing those who might not be.

Platforms Pour Money Into Alternative Investments Infrastructure, Suggesting That Enough Advisors Are Adopting Alternatives To Be Worth The Cost

For many years, alternative investments such as private equity, private debt, and hedge funds were primarily the purview of institutional investors like pension plans, foundations, and endowments, with only a tiny slice of the market taken up by high-net-worth individual investors. But over the last decade, alternative asset managers have made a push to make their products more available to individual investors – both on account of demand for capital by private companies that are refraining from going public far longer than they once did, and because in a world where low-fee index investing has come to dominate the public market, firms can still earn comparatively high fees on the private funds they manage. And so asset managers have sought to distribute alternatives both directly to retail investors (e.g., via interval funds and private market ETFs) and through financial advisors (e.g., via inclusion in model portfolios and TAMPs, and through alternatives exchange platforms like CAIS and iCapital).

As a result, advisors' use of alternatives has crept up over time; however, alternatives are still generally only used by a minority of advisors, and even among those advisor who do allocate to alternatives they still represent a relatively small slice of clients' portfolios. There's still considerable debate over the role of alternatives and whether they're consistent with advisors' fiduciary duty to act in their clients' best interests. On the one hand, advocates of alternatives argue that their performance track record and lower volatility compared to public markets make them a valuable diversifier in client portfolios. But on the other hand, others argue that the relatively infrequent valuation of most private investments makes them only seem less volatile than public markets, and that any outperformance they achieve is often eaten up by the higher fees that they charge.

Still, as several news stories from the last month show, technology providers, asset managers, and VC firms are pouring money into their alternative asset infrastructures even though advisor adoption has been comparatively muted. First there was Morgan Stanley announcing its acquisition of EquityZen, a platform for trading shares of individual privately held companies. Next there was Charles Schwab announcing its own purchase of a private share trading platform in Forge. Then there was the TAMP GeoWealth launching a new model marketplace offering models combining public and private investments, which has been in the works for more than a year since GeoWealth announced a partnership with (and investment from) BlackRock and a subsequent partnership and investment from Apollo. And finally there was Bridge, a performance reporting and monitoring platform for private investments, announcing a $5.1 million seed funding round.

It's striking to see the amounts being invested into building out the alternative asset infrastructure despite its relatively low adoption compared to standard publicly traded assets. Even though adoption has crept up in recent years, the amount that advisors allocate to alternatives as a portion of clients' overall portfolio assets is still less than 10%. In spite of increased access to alternatives, few advisors are making it a big part of their clients' portfolios, suggesting that at best advisors view alternatives as a diversifier to the stock-and-bond sleeves but not as a core asset class to build the portfolio around.

Which really goes to show just how much margin there is in alternative investments at the moment, especially with the economics of basis points-based platform fees. If advisors manage assets on the order of trillions of total dollars, then an average 10% allocation to alternatives equates to hundreds of billions of dollars. Which means that earning just a fraction of a percentage of that amount to facilitate the distribution of those alternative assets represents an opportunity of hundreds of millions of dollars in annual revenue. In that context, it's reasonable to see why providers are investing in building out their alternatives capabilities, since even if the total alternatives allocation continues to hover around 10%, the ability to participate in a $100 billion-plus asset market can easily justify the opportunity.

Ultimately, while the fervor over expanding alternatives may die down at some point, it's more than likely that alternatives adoption won't go away entirely. In the meantime, for advisors seeking access to alternatives, there are more and more channels for them to do so, whether that's on dedicated alternatives exchanges like CAIS and iCapital or, increasingly, on platforms that they already use like custodians (e.g., Schwab) and TAMPs (e.g., GeoWealth). Which in the end might not completely reshape how advisors think about alternatives, but can at least make it easier to integrate into client portfolios to the extent it's appropriate to do so.

How Altruist's Hazel Exemplifies The Path AI Notetakers May Take To Replace CRMs As The Interface For Client Data

The original function of CRM systems was as a digital Rolodex for storing information on clients like contact details and notes from prior interactions. But beyond being just a repository for client data, the CRM also needed to serve as an interface for that data: It needed to allow users to easily locate a client's file and pull up any information that they needed to find. This interface function became more and more important over the years: As advisors increasingly adopted the more ongoing-service relationship-based RIA model, and the length of their client relationships grew, the amount of data for each client grew in turn. And as CRMs began to link digitally to other systems such as custodial platforms and financial planning software, the amount of data that could be accessed through the CRM for each client grew exponentially. Which ultimately has led to CRMs becoming the most popular "hub" for advisory firms (according to the latest Kitces AdvisorTech Research), and the first platform that the advisor logged into every day: in essence, CRMs are now the place to find almost any piece of information that the advisor (and their team) needs to know about when interacting with a client.

Except in practice, CRM platforms have often struggled to define and optimize their role as an interface between the advisor and their client data. Many data points that don't come in the CRM's out-of-the-box configuration require building custom fields, which in turn necessitates the advisor sinking their own time into configuring the CRM (or hiring a consultant to do it for them) just to access and view the data they need. Historical client information can also be difficult to resurface, such as details buried in what can eventually become dozens or more than 100 prior meeting notes. And although some CRMs have built out other features like workflow and task management capabilities to run off of their underlying data, those capabilities don't solve for the underlying difficulties in advisors' ability to use client data to effectively run their practices. Hence, despite advisors acknowledging the importance of their CRMs to their day-to-day business (since there's nowhere else that advisors can access so much information about their clients in one place), many are lukewarm about how well their CRMs actually perform in that role – as shown in the most recent Kitces Research on Advisor Technology, which showed that despite being one of advisors' most highly adopted types of technology, they received an average of only a mediocre 7.5 out of 10 satisfaction rating from those advisors.

Normally, such a discrepancy between the importance of a piece of technology and users' happiness with the technology in practice would be a sign that the technology is ripe for disruption from a new competitor. However, in the CRM space, the sheer amount of data that lives in an advisor's CRM system from years and years of client interactions – which would all need to be moved to a new provider if the advisor decided to switch – serves as a significant obstacle for advisors who might otherwise be ready to move to a different system. But what if a different type of technology came along that made it easier for advisors to make use of the data that's already in their CRM, without having to move it into a different system?

Enter the AI notetakers, which have proliferated to number over a dozen different advisor-specific solutions over the past two years. In their original and most basic form, AI notetakers would simply transcribe the dialogue from client meetings and create notes and follow-up summaries to send to the client. Advisor-specific tools like Jump, Zocks, and Finmate AI would also integrate with CRM systems like Wealthbox and Redtail to push meeting notes into the CRM for archiving and populate follow-up tasks for advisory team members. But more recently, meeting note tools have also been increasingly pulling data from the advisor's CRM, e.g., to create meeting agendas and surface talking points based on information in prior meeting notes.

And from that point, it's only a relatively short step to AI notetakers pulling in even more client data, from both the CRM and other sources like financial planning software and custodial platforms. Which is what we're now starting to see, for example, with Altruist's Hazel meeting assistant which has recently announced that it is now able to pull in custodial data for clients on the Altruist platform (in addition to CRM, email and calendar apps).

But as AI notetakers begin to draw in more and more client data from multiple sources to synthesize into tasks and talking points for advisors, it's worth asking whether or at what point AI notetakers will effectively usurp the CRM's role as the primary interface between advisors and their clients' data?

After all, since their inception, one of the most consistent strengths of LLM-based AI tools has been the ability to synthesize lots of data from many sources and query against it to highlight key information. Which would have made AI tools well-suited for integration into CRM tools in the beginning, since that is effectively the role that CRMs have attempted to serve for many years (but have struggled with because of the limitations of non-AI to query the sheer amount of data that CRMs pull together, especially for clients with years or even decades of client history). Except the most-used CRMs for advisors were slow to adopt AI, with Wealthbox only releasing its integrated AI notetaker in the fall of 2025 and Redtail apparently having yet to roll out any of its own substantive AI tools at all. Which has left standalone tools to fill in the void, as Altruist's Hazel has now done.

One big question for the future of advisor technology, then, is how the role of CRM systems will shift as AI meeting note tools evolve to become more of an AI "operating system" interface for advisors. On the one hand, if an advisor isn't happy with how difficult their CRM makes it to find and make use of their own client data, but dreads the prospect of having to port all of that data over to a different CRM, it might make sense for them to adopt a new tool such as Hazel to serve as their new interface while keeping their data where it is in the original CRM – effectively relegating the CRM back to its long-ago role as a simple repository of client data.

But on the other hand, CRM providers will be loath to cede their role as the advisor's hub to standalone AI tools (hence Wealthbox launching its own notetaker, albeit belatedly), and advisors might be reluctant to add a new tool to their tech stack to replicate a data interface function that their CRM already does (even if it doesn't do it as well as they'd like). But if AI-driven systems like Hazel really do present a material improvement over the interfaces of existing CRM systems, and those CRM systems continue to be slow to update their own interface capabilities, they could find themselves being sidelined in favor of increasingly powerful AI tools or even replaced entirely by an AI-native CRM like Slant or a combination of an AI interface like Hazel and a data warehousing solution like Invent or Milemarker.

Ultimately, advisors are generally slow to make big changes in technology, and the vast amount of data stored in CRM systems keeps them relatively protected from quick disruption. But the rise of increasingly powerful AI tools has given advisors an opportunity to rethink how they want to interact with their data in the future – and whether a CRM is really the right system for them to do it in.

Mobile Assistant Turns Down Offers To Sell Client A Decade Of Data For AI Training – But Will Other Technology Vendors Make The Same Choice?

Keeping client data safe has long been a concern for financial advisors, both for regulatory purposes, and simply to ensure clients themselves are protected and well-served. With all the data that gets stored in different technology systems, from names and addresses to Social Security and account numbers, the consequences of that data falling into the wrong hands can run the gamut from merely annoying (e.g., ending up on text or email distribution lists the client has no interest in) to much more serious financial impacts (e.g., the client having their identity stolen by a bad actor who empties their bank accounts before they can do anything about it). And so it's important for advisors that the third party vendors that they use have strong data protection policies and won't sell or disclose personal client information to other parties without authorization or a business purpose directly related to providing the vendor's services.

But while advisors don't expect their vendors to sell any of their clients' private personally identifiable information, those vendors are often sitting on a trove of other data that isn't as protected, from transaction histories to credit scores to investment positions. When this data is anonymized to remove any identifying information, it can still reveal insights about individuals' behaviors that advertisers (and technology companies like Google and social media platforms like Meta that sell to advertisers) are willing to pay for. And in a world where countless companies, from startups to mega-corporations, are clamoring to build and roll out LLM-based AI tools, one particularly valuable form of data is text, from correspondence to transcripts of conversations, that can be used to train those models.

All of which raises the question of: If advisors' technology vendors aren't directly selling their clients' personal data, is there nevertheless client data (with personally identifiable information scrubbed away) that those vendors are selling or monetizing in some way? Which seems not only relevant for the vendors that advisors are using today, but also for any vendors that the advisor has used in the past which might still be sitting on client data. Because it isn't necessarily a given that once an advisor stops using a piece of technology, that technology's vendor will automatically delete all of that advisor's client data. For instance, often they may keep the data archived in case the advisor decides to come back in order to ease the re-onboarding process. But in that case, it isn't always clear who fully owns the rights to that data, and whether the technology company can use it for business or other purposes such as training AI tools – since often there was no way to foresee that even being a possibility when the advisor originally signed the agreement with the vendor.

One powerful reminder of the thorny questions around who can use client data for which purposes was the story that came out this month about Mobile Assistant considering – but ultimately declining – to sell its anonymized user data (in particular, more than a decade of call transcripts) for AI training purposes. As one of the original pre-AI meeting transcription services in which advisors' client meetings were hand-transcribed by human transcriptionists, Mobile Assistant has data on client conversations (and advisors' dictated notes about those meetings) going back 14 years since its founding in 2011, encompassing a reported 5 million separate client meetings. All of that data, with its millions of real-life examples of the interactions between clients and advisors and the concerns, explanations, and recommendations that come out of those meetings, could prove immensely valuable to technology companies training their own AI meeting assistants. So as Mobile Assistant considered its options in light of the huge number of AI notetakers that had quickly threatened to make its human transcription model obsolete, it considered whether to leverage its trove of meeting data as an asset to boost its value in a potential sale.

The irony, however, is that when Mobile Assistant was ultimately acquired by the AI notetaker Jump in October of 2025, the deal did not include any of Mobile Assistant's data; instead, the acquisition was primarily about acquiring and distributing Jump to Mobile Assistant's existing user base. Mobile Assistant instead reportedly decided to take the high road and delete the client data it still had on file, rather than to continue shopping it to potential acquirers.

It should be said that the episode generally reflects well on both Mobile Assistant and Jump. Although Mobile Assistant did reportedly explore the sale of its anonymized transcription data, it ultimately opted not to. And Jump, which claims not to use any internal client data in training its own LLM, chose not to buy an outside set of real-life client interactions to further train its models (although it isn't clear exactly what data Jump did train its models on in the first place).

But from a broader perspective, the story serves as a telling reminder that even though advisors may think that their technology vendors won't sell or monetize their clients' information in any way (or may have thought so when they first signed their vendor agreement), the conversations that go on behind the scenes show that some providers might at least be considering it or be counseled to explore it as another way to monetize their businesses.

Which makes it all the more important for financial advisors to understand what their technology vendors can and can't do with their client's data, both while the advisor is using the vendor and (especially) if and when the advisor terminates the contract. It might not always be practical to insist that the vendor deletes all client data immediately – sometimes there are legitimate internal business purposes that a vendor may want to keep anonymized versions the data on hand, from supporting returning users, to regulatory retention requirements, to simply using the data to better understand user behavior to improve their own product – but if the vendor is allowed to keep client data on hand, then it's worth asking what exactly they're allowed to do with it. At the very minimum, advisors may want to see in writing that the vendor isn't allowed to sell the client's data, in any form, on a standalone basis. Because as is clear from the story about Mobile Assistant, with more ways than ever to monetize even anonymous versions of client data in the age of AI, it may be increasingly tempting for some vendors (especially those that are struggling to keep pace amidst technological disruption) to sell that data – even if their (current or former) users never even considered it possible when they signed up.

In the meantime, we've rolled out a beta version of our new AdvisorTech Directory, along with making updates to the latest version of our Financial AdvisorTech Solutions Map (produced in collaboration with Craig Iskowitz of Ezra Group)!

So what do you think? Can AI Notetakers eventually become the new front-end operating system that displaces CRM systems? Will tools that make prospecting easier trigger more advisors to start cold prospecting, or is the appeal still limited? Are there standard contractual provisions that advisors should require from their AdvisorTech vendors as it pertains to the use of historical data? Let us know your thoughts by sharing in the comments below!

The first link in the Mobile Assistant story is broken, FYI