Executive Summary

In recent years, financial advisors have increasingly embraced tax planning as a core element of delivering value to clients. This shift reflects the reality that taxes permeate virtually every financial decision clients make – whether related to investing, retirement, business structure, or charitable giving – and often represent one of the largest expenses faced by clients over their lifetime. Historically, tax-related services within advisory firms were primarily focused on investment strategies, like using ETFs for their tax efficiency or implementing asset location and tax-loss harvesting strategies to boost after-tax returns. But as the profession has evolved toward more holistic planning, tax considerations have likewise expanded into more areas of advice, including Roth conversions, charitable strategies, and small business structuring.

Despite this growing interest in tax conversations, most advisors are still quick to distinguish their services as "tax planning", not "tax advice" – a distinction largely driven by liability concerns. While common wisdom suggests that only CPAs, EAs, or attorneys are authorized to give tax advice, this is only strictly true in limited contexts, such as in promoting abusive tax shelters. The broader concern is that giving actionable tax advice can expose advisors to legal and financial liability, especially since RIA compliance policies and E&O insurance typically only cover investment advice. As such, advisors who provide specific tax recommendations (like exact Roth conversion amounts), without the backing of a tax professional, risk legal and financial penalties if those recommendations result in unintended tax consequences.

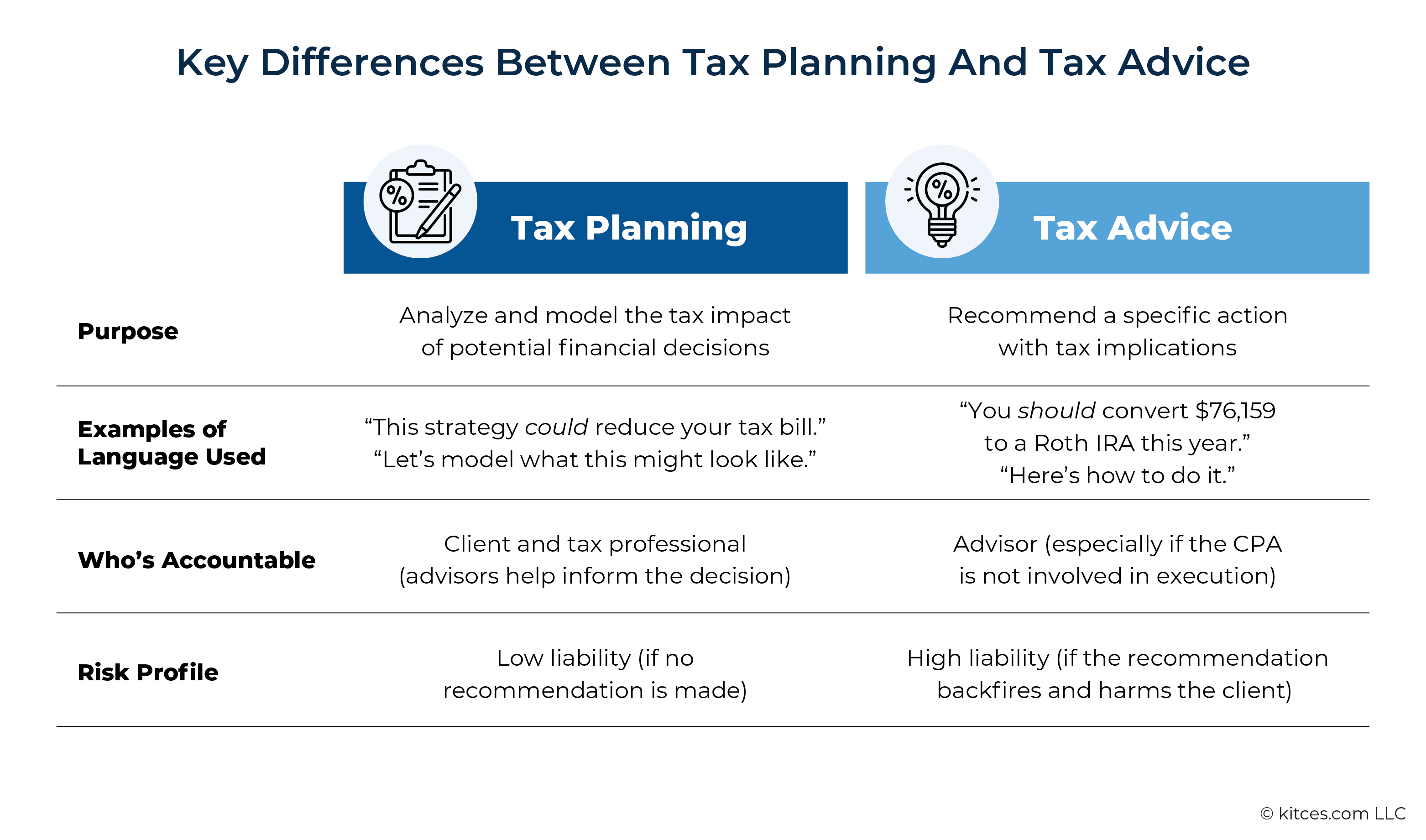

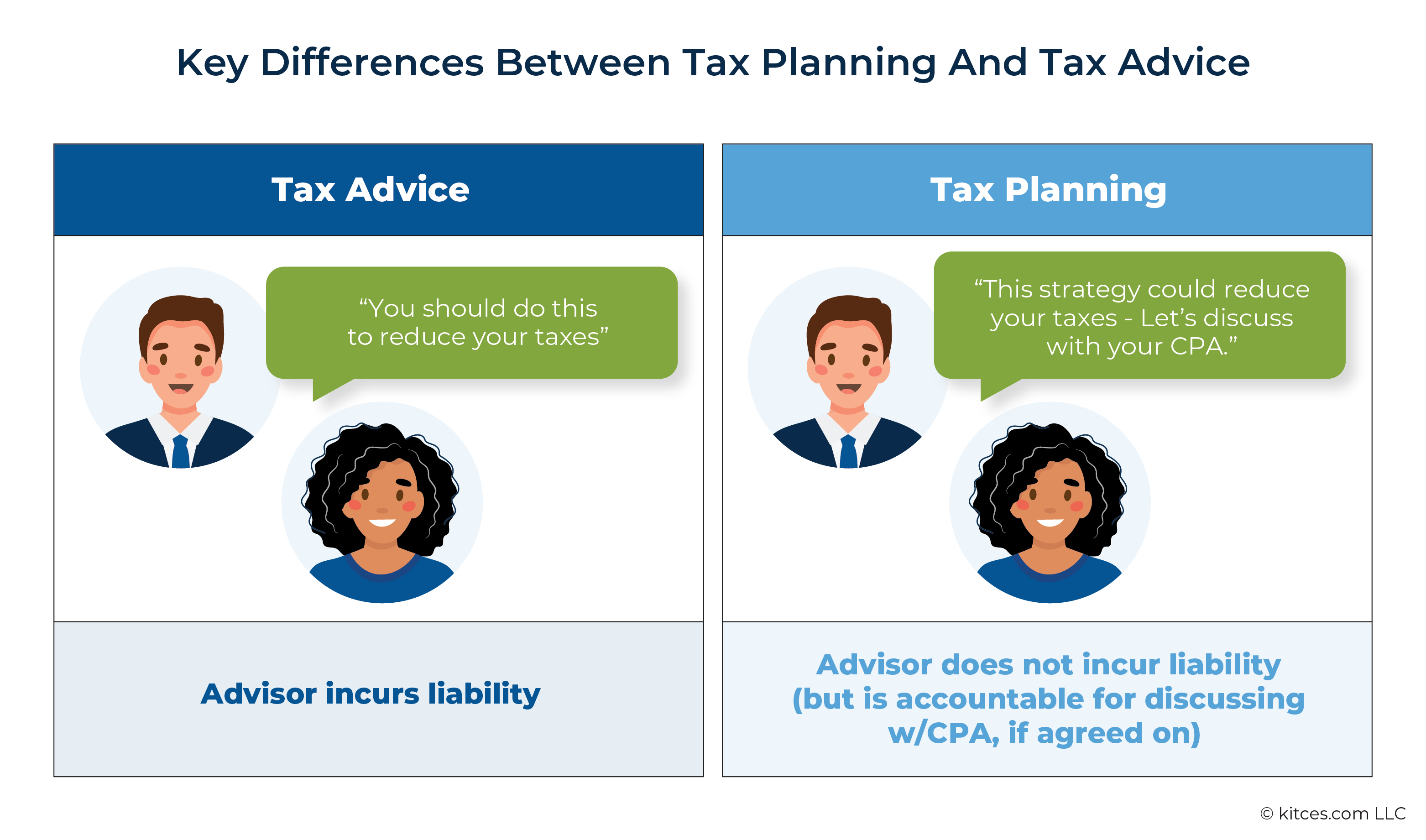

Understanding the difference between tax planning and tax advice is crucial for advisors seeking to stay on the right side of this liability line. Tax planning may involve discussing general tax rules, modeling hypothetical scenarios, or analyzing the tax impact of strategies for the client – without actually making concrete recommendations. Tax advice, by contrast, involves discussing specific actions with tax consequences, which can expose advisors to significant legal risk, particularly when clients interpret such statements as recommendations. Given how easily clients may conflate a discussion of potential tax savings with an endorsement to act, advisors must be extremely careful in how they communicate tax-related strategies.

Additionally, recent developments in advisory firm practices and technology have further blurred the lines between planning and advice. For instance, the rise of live, collaborative planning sessions in lieu of static, written reports means there are fewer opportunities for advisors to append disclaimers clarifying that they don’t intend to give tax advice. At the same time, the emergence of sophisticated tax planning software like Holistiplan and FP Alpha introduces a higher level of precision and actionability to advisors’ planning conversations, increasing the change that suggestions may be construed as advice.

To navigate this environment, advisors may consider a two-part strategy: First, by proactively setting expectations during meetings with a clear verbal preface explaining that tax advice falls outside the scope of their role; and second, by documenting the conversation to clarify what was discussed, explicitly note the absence of a formal recommendation, and reiterate the importance of consulting a qualified tax professional. This step is especially important in spontaneous or emotionally charged situations where advisors may feel pressure to respond quickly. AI meeting notetakers can assist in documenting these interactions, but advisors should review the tools’ output carefully to ensure no inadvertent ‘recommendations’ are implied.

Ultimately, the rising integration of tax strategies into financial planning is a positive development that enhances the value advisors can deliver. But it also demands new considerations in how those strategies are presented. By clearly delineating the boundary between planning and advice, and by proactively communicating and documenting that boundary, advisors can continue to offer high-impact tax insights while protecting themselves and maintaining the trust of their clients.

The Rise Of Tax Planning As A Value-Add

There’s a growing focus among financial advisors on providing value for their clients through tax-related strategies.

Taxes are entwined with peoples’ financial lives – it’s hard to think of a financial decision that doesn’t involve at least some tax component, from investment strategy to home ownership to life insurance to business ownership and on and on. Taxes also represent one of the largest expenses individuals face over their lifetimes: Between Federal payroll taxes (7.65% of compensation), Federal income taxes (10%–20% of taxable income for most households), and state taxes (around 1%–5% for households in states with income tax), taxes can eat up 20%–30% (or more) of a person’s lifetime income. For financial advisors, of course it makes sense to find ways to help reduce the burden of taxes on clients’ financial lives.

In the days when most financial advisors’ focus was on managing clients’ investment portfolios, efforts to find tax savings were mainly concentrated on investment management, as advisors sought to differentiate themselves by offering more tax-efficient investment strategies. For example, after the advent of ETFs in the 1990s and early 2000s, many advisors shifted their asset allocation models away from mutual funds and toward ETFs in part to avoid the annual (taxable) capital gains distributions that most mutual funds generate. And as portfolio rebalancing technology improved in the 2010s, advisors also started employing household-level asset location and tax-loss harvesting to further reduce the tax impact of clients’ investment portfolios in taxable accounts.

More recently, as the financial advice industry has shifted toward more holistic planning, advisors have also expanded the ways they help clients manage taxes beyond the investment portfolio. For example, advisors helping clients with retirement planning often recommend Roth conversions and tax-efficient withdrawal strategies to reduce the tax burden on retirement savings. Or they may recommend charitable giving strategies like Donor-Advised Funds to enhance the tax benefits of their clients’ donations. Or they may work with business owners to determine the best business structure (like a partnership, S corporation, or C corporation) to minimize tax liabilities while also meeting the owner’s needs for business control, asset protection, and administrative complexity.

Why Financial Advisors Say They Don’t Give Tax Advice

All the while, however, most advisors – even the ones who lean heavily into tax – generally insist that they don’t give tax advice, but instead are merely engaged in tax planning. Put differently, most advisors claim that they aren’t recommending specific tax strategies; rather, they’re estimating the impact of taxes on their client’s situation in different scenarios, while leaving the door open for a credentialed tax professional to run the final numbers and decide exactly how the client should implement their chosen strategy.

Some advisors say they don’t give tax advice because only credentialed tax professionals – such as Certified Public Accountants (CPAs), IRS Enrolled Agents (EAs), and attorneys – are allowed to do so. However, this interpretation is a bit of a myth. While it’s true that only credentialed tax professionals may give certain types of written tax advice, those restrictions generally apply only to tax shelters, listed transactions, and other potentially abusive tax avoidance schemes. The IRS has rarely, if ever, disciplined an advisor who wasn’t a CPA, EA, or attorney for providing tax advice when that advice is based on a straightforward interpretation of tax law.

The real reason most advisors want to avoid giving tax advice (and why many larger firms restrict advisors from virtually any discussion of their clients’ taxes) is liability. When a trusted professional offers paid advice, they are legally and financially accountable for that advice – meaning that if the advice ends up being harmful to the client, the client can sue to be compensated for that harm.

Financial advisors – many of whom have roots in portfolio management and operate under the umbrella of a Registered Investment Adviser (RIA) firm – are generally well-positioned to protect themselves from legal liability pertaining to their investment advice. RIAs are required to maintain policies and procedures to ensure their advisors act in clients’ best interests when making investment recommendations. Additionally, RIA Errors & Omissions (E&O) insurance, which covers financial liability for advisor actions, reimburses financial penalties and legal fees for liabilities stemming from an advisor’s investment advice.

By contrast, most advisory firms (unless they have an in-house tax preparation or tax advice arm) are not set up to protect themselves from liability for giving tax advice. Their compliance policies don’t encompass the delivery or supervision of tax advice (because, unlike investment advice, they aren’t required to), and their E&O coverage often specifically excludes liability for taxes and penalties owed by clients due to an advisor’s tax advice.

This matters not just because of the potential for advisors to suffer financial consequences as a result of giving tax advice – it’s also important for ensuring that clients receive quality guidance. Professional liability rules exist to make certain that when clients put their trust in a professional’s advice, the professional is accountable for that advice. The potential for consequences in cases of negligence – which can even include imprisonment in cases of outright fraud – incentivizes the professional to take care in ensuring their advice is sound.

Ultimately, if a firm isn’t equipped to handle the legal or financial liability of giving tax advice, it can’t truly be accountable for that advice. And that accountability is what backstops the fiduciary duty that applies across all types of financial advice. Put differently, if an advisor isn’t in a position to make a client whole in the case of financial harm caused by the advisor’s own negligence, then they shouldn’t be offering that advice in the first place.

The Difference Between Tax Planning And Tax Advice

If a financial advisor wants to avoid giving tax advice (which may incur liability for them) but still wants to offer tax planning, it makes sense to draw some kind of distinction between the two.

In a nutshell, tax advice is effectively a call to action. It tells the client that they should do something – convert assets to Roth, contribute to a certain type of account, structure a charitable donation in a certain way, etc. – and often sets forth how it should be done.

By contrast, tax planning is more about analyzing and discussing the impact of taxes on a client’s financial picture. Advisors can give general information on tax laws and regulations, discuss how certain tax provisions might affect a client’s situation, and model different scenarios and their tax impact – all without giving tax advice – as long as they don’t ultimately recommend a specific course of action.

For instance, imagine that an advisor meets with a client who plans to retire next year. The advisor uses their financial planning software to show how the client could convert some of their pre-tax retirement assets to Roth during their early retirement years when their other taxable income would be minimal, which would allow the client to pay taxes on those dollars at a relatively low marginal rate. In the advisor’s model, the client could convert about $75,000 to Roth each year for five years. The advisor and client agree to revisit the plan after the client’s retirement and, if the strategy still makes sense, consult the client’s CPA to calculate the exact amount to convert each year.

At first glance, there’s not much in the scenario above that could be construed as ‘tax advice’ on the advisor’s part. Although they discuss the Roth conversion strategy with the client and even show how it could increase the portfolio’s after-tax value by converting assets to Roth at low marginal tax rates, the end result of the discussion does not involve a concrete recommendation to move forward with the strategy. Rather, it’s a forward-looking plan that will be revisited before taking action; and even then, the CPA will run the final calculation for them.

Nerd Note:

The advisor is still responsible for following through with any agreed-upon action items stemming from the tax planning discussion, even if the discussion didn’t involve any actual tax advice. For example, if the advisor recommends having a discussion with the client’s CPA about a particular tax strategy, the advisor is still accountable for making sure that conversation takes place.

Notably, the conversation has still provided value for the client: without it, the client may not have even known about the possibility of Roth conversions or understood the potential tax impact in retirement. However, that value comes more from long-term planning, not immediate actionability.

Now imagine a different scenario. Suppose the client returns in the year after they retire, and they pick up the Roth conversion discussion. The advisor has started using new tax planning software that allows them to upload the client’s prior-year tax return and build a projection based on those numbers. The advisor adjusts the income inputs to account for the client’s retirement and models a Roth conversion for the current year. Confident in the software’s calculations, the advisor and client agree to proceed with the Roth conversion in the amount calculated by the software – without consulting the client’s CPA.

Fast forward to tax season – when oops! – it turns out the client had forgotten to mention a major new source of income: distributions from a trust of which they are the sole beneficiary. Which means the Roth conversion is taxed at a much higher marginal rate than anticipated. When the client receives the tax return, they’re angered by the large tax bill due and demand that the advisor compensate for the difference between the expected and actual owed.

In this instance, it’s much harder to argue that the advisor didn’t give some form of tax advice: They walked the client through the calculation, determined a specific amount to convert to Roth, and made a recommendation without the assistance of the client’s CPA. In the client’s eyes, that certainly amounted to a recommendation to take a specific course of action. And ultimately, as the source of the recommendation, the advisor is accountable for any financial harm that results – in this case, the tax consequences of the oversight.

The Risk Of Advisors Giving Inadvertent Tax Advice

Over the years of presenting on tax advice and tax planning, I’ve found that most advisors insist they don’t give any tax advice, even if they do an extensive amount of tax planning in their practice. But, as shown in the examples above, it can be easy for an advisor to stray into the realm of tax advice – even unintentionally – when they say something the client interprets as a clear recommendation on a tax strategy. And once the advisor makes that recommendation, they are professionally accountable – and may be legally and/or financially liable – for the results.

As easy as it may sound to simply avoid making recommendations, the reality isn’t always so straightforward. What might seem to the advisor like a discussion of potential tax strategies with no specific recommendations – and thus doesn’t constitute advice – might still come across as advice to the client.

Taken at face value, "Strategy X could save you some money on taxes" might sound like a neutral statement of fact since it merely states what might happen if the client implements Strategy X. But from the client’s point of view, it could easily sound like a recommendation – especially if they were to read between the lines. Because if the strategy were to save them money on taxes, why wouldn’t they go ahead with it? And if the client is expecting a recommendation – which would be fairly reasonable, given that the advisor likely makes recommendations to the client on other financial topics – then they’ll most likely hear one, unless the advisor clearly states otherwise.

For advisors who want to avoid the liability risk of offering tax advice, but still want to provide value for their clients around taxes, it’s necessary to implement guardrails that keep the discussion firmly in the realm of tax planning, not advice.

A common precaution advisors take is to include disclaimers on written materials like emails and reports along the lines of, "We do not provide tax advice, and the contents of this report/correspondence should not be construed as or relied on as tax advice. Please consult a tax professional for recommendations regarding any strategies discussed in this report/correspondence". There may also be a provision in the RIA’s Advisory Agreement that excludes the rendering of any tax (or legal) advice from the scope of the engagement unless specifically agreed to otherwise.

While these blanket measures might make sense as an initial step, they aren’t foolproof. An advisor might still inadvertently provide tax advice and face unexpected liability if the advice doesn’t turn out in the way the client expects.

How To Avoid Giving Inadvertent Tax Advice

As noted above, many advisors include disclaimers in written client communication (e.g., at the end of client emails, reports, or other written planning materials) stating that they aren’t giving tax advice. However, these disclosures don’t necessarily cover verbal statements made during meetings or phone calls. And verbal advice to a client is still advice for which the advisor could be liable.

The issue of giving verbal advice is becoming more relevant as financial advisors move away from delivering traditional printed comprehensive financial plan documents and toward a more collaborative, interactive approach. Increasingly, advisors use financial planning software live and on-screen during video or in-person meetings. According to the most recent Kitces Research on the Financial Planning Process, more than half of advisors (53%) now primarily use a collaborative approach to delivering financial plans. That number has grown steadily in recent years as video meetings and screen sharing have become common, and the planning software tools have become more optimized for live, collaborative planning rather than generating printed reports.

While collaborative planning has arguably improved the quality and engagement of advisor–client conversations, it creates a new challenge: There’s no written document where a disclaimer can be included saying that the discussion shouldn’t be construed as tax advice. Put differently, collaborative planning can be so effective at helping advisors communicate their advice that it can ironically blur the line between what is or isn’t actually intended to be advice unless the advisor specifically makes a point to clarify that distinction.

Additionally, the widespread adoption of increasingly sophisticated tax planning tools – like Holistiplan and FP Alpha– introduces a degree of precision into advisors’ tax planning. These tools allow advisors to easily upload their clients’ prior-year tax returns and model future scenarios in far greater detail than traditional comprehensive financial planning software. As a result, advisors can now create ‘optimized’ short-term tax projections, such as calculating the exact amount of pre-tax dollars to convert to Roth in order to fill up a specified income tax bracket.

This precision, while appreciated by many advisors frustrated with the limitations of older software (and reluctant to use software like BNA Tax or Lacerte that could produce detailed tax projections but were too laborious and expensive), also increases the risk that the advisor’s tax planning discussions could be interpreted by the client as tax advice. For example, telling a client they could convert "around $75,000" implies there is still some flexibility over what the exact number will be. But telling them they can convert exactly $76,159 has more of a sense of finality that may not be warranted if there’s any uncertainty about the client’s taxable income for the year.

In this environment, it’s clear that disclaimers on printed reports and emails aren’t enough to safeguard advisors from liability – especially in a world where more financial planning is done through live, collaborative conversations. Instead, advisors may need to consider a more proactive approach in how they describe which parts of the conversation are ‘advice’, and which are merely ‘planning’.

A good way to do this is by taking a two-pronged approach. First, begin the conversation with a verbal preface to set expectations before discussing actual planning strategies. Then, follow up in writing to reinforce the discussion and provide a written record of the conversation, especially in the absence of a printed report where a disclaimer might otherwise be included.

The Verbal Preface

The verbal preface would typically come at the beginning of any tax planning discussion and is primarily about setting expectations, especially for clients primed to expect concrete recommendations from the advisor on all topics, including tax.

An example of the preface could be something like:

One of my goals is to help you pay the least amount of tax that you legally owe, and in our meeting today we’re going to discuss some tax planning strategies that I think may help achieve that aim.

However, giving tax advice is not within the scope of what I do as a financial advisor – I always leave that up to a qualified tax professional who is willing to be fully accountable for their recommendations.

So I’d like to make sure that before we agree to move forward on any of the strategies we discuss today, we consult with your tax professional so we can be more confident that it will work out as we intend it to.

When a meeting is scheduled in advance, it’s usually straightforward to make sure that such a verbal preface is added to the meeting agenda. But in many cases, tax planning conversations might take place without much notice, leaving the advisor without the luxury of planning in advance.

For example, an advisor gets a phone call from their client whose parent is in ill health and may not have much time left. The client, acting as power of attorney, wants to know if there is anything they should do now to minimize the tax consequences of inheriting the parent’s retirement accounts.

A situation like this presents two primary challenges: First, there may not be time for the advisor to fully analyze the client’s financial situation or evaluate different strategies. Second, the client may be overwhelmed and emotionally exhausted; they may just want a clear recommendation, not a detailed analysis.

So what should the advisor do to support the client while also protecting themselves from liability?

The answer depends on how comfortable the advisor feels in answering the question ‘live’ during the phone call. Even when there’s pressure to provide a quick answer, an advisor is still governed by their fiduciary duty, which means they expected to exercise reasonable care to recommend a strategy that’s in the client’s best interest. If that care isn’t possible in the moment, the best course of action may be to pause the conversation and follow up when they have enough information – and time – to make an informed analysis, hopefully while there’s still time for the client to act on the recommendation.

Assuming that the advisor does feel like they can answer the question in the moment over the phone, however, they may still want to avoid giving a direct recommendation, particularly if there’s a risk that the guidance could be interpreted as tax advice. Instead, in a tax planning context, they could still discuss the different considerations involved, such as how inherited retirement accounts could be subject to the 10-year rule and trigger Required Minimum Distributions (RMDs) during that period.

But even in these spontaneous conversations, the advisor can still set expectations by prefacing that discussion with a verbal disclaimer like:

I understand how overwhelming this may feel, and I’m here to talk through some potential strategies with you. But I want to be clear that I’m not qualified to give tax advice in this – or any – situation.

Let’s make sure that we also run these strategies by your tax professional before moving forward on anything.

Setting the tone this way ensures the client understands the purpose of the call and won’t be looking for a specific recommendation to take away from it.

Documenting Verbal Conversations

In addition to setting client expectations verbally before the conversation, advisors can also protect themselves from liability by documenting the conversation after the fact. Even if the advisor clearly states that they aren’t giving tax advice, having a written record to show what was discussed during the call or meeting can be critical if questions arise later – otherwise, it may come down to the client’s word against the advisor’s.

This documentation might take the form of a CRM note summarizing the conversation and any strategies discussed. It could also be a follow-up email to the client listing the key points of the conversation and reiterating the need to consult with a tax professional before implementing any strategies.

Either way, the documentation should be clear about what was discussed and whether any recommendations were made or follow-up actions for the client or advisor were identified.

Nerd Note:

The advent of AI-powered meeting notetakers – such as general-purpose notetakers like Fathom or Zoom’s AI Companion, or advisor-specific options like Jump or Zocks – has made it easier to generate summaries of meeting highlights for the advisor’s CRM or follow-up emails.

However, it’s important to carefully review any meeting summaries automatically generated by AI. If an AI-generated note states that the advisor "recommended" a tax planning strategy when the intent was only to discuss the implications, it should be edited to correctly reflect that no recommendations were made.

That said, how an AI tool interprets the discussion might be a helpful litmus test: If a neutral AI bot characterizes something as a recommendation, it may signal that the conversation veered too close to ‘advice’, despite the advisor’s intention to stay within planning territory.

Notably, when tax planning strategies discussed in the meeting need to be reviewed by a tax professional, the follow-up email can be a good place to set up that conversation.

If the advisor and tax professional are already acquainted, this section can read something like:

As you might recall discussing during the meeting, I would like to get [tax professional]’s approval before moving forward with this strategy. Are you OK with me emailing them to start that conversation?

If the advisor has not met the tax professional before, the section could read as:

As you might recall discussing during the meeting, I would like to get the approval of your tax professional before moving forward with this strategy. Are you willing to send an introductory email to introduce us to each other, and we can take the conversation from there?

Either way, documenting not only the planning strategies discussed but also the advisor’s intent to rely on the judgment of a qualified tax professional strengthens the case that the advisor isn’t giving tax advice themselves.

Ultimately, the increasing focus on tax planning among financial advisors is a good thing, because it signifies a further shift toward holistic advice and consideration for the real-life tax consequences of clients’ financial decisions.

But it’s also worth remembering that this shift involves moving into a new domain of advice, separate from investments and portfolio management where advisors have their roots, and with its own professional and regulatory framework surrounding it. Which means broaching the subject of taxes requires careful examination of the legal, ethical, and professional boundaries between investment and tax advice to ensure that both sets of standards are being adhered to. Unknowingly creating legal or financial liability poses a risk not only to the advisor but also to the client, who expects their trusted professional to be accountable for the advice they give.

The good news, though, is that once the line between tax advice and tax planning is clearly drawn, and expectations are established for both the client and advisor, it becomes easier to have confident, productive conversations around taxes – and to continue adding value while ensuring that both the client and the advisor remain protected!