Executive Summary

For the past 20 years, due both to the growing research on safe withdrawal rates, the adoption of Monte Carlo analysis, and just a difficult period of market returns, there has been an increasing awareness of the importance and impact that market volatility can have on a retiree's portfolio. Often dubbed the phenomenon of "sequence risk", retirees are cautioned that they must either spend conservatively, buy guarantees, or otherwise manage their investments to help mitigate the danger of a sharp downturn in the early years.

One popular way to manage the concern of sequence risk is through so-called "bucket strategies" that break parts of the portfolio into pools of money to handle specific goals or time horizons. For instance, a pool of cash might cover spending for the next 3 years, an account full of bonds could handle the next 5-7 years, and equities would only be needed for spending more than a decade away, "ensuring" that no withdrawals will need to occur from the portfolio if there is an early market decline.

Yet the reality is that strict implementation of a bucket strategy is more than just an exercise in mental accounting; it can actually distort the portfolio's asset allocation, leading to an increasing amount of equity exposure over time as fixed income assets are spent down while equities continue to grow. Yet recent research shows that despite the contrary nature of the strategy - allowing equity exposure to increase during retirement when conventional wisdom suggests it should decline as clients age - it turns out that a "rising equity glidepath" actually does improve retirement outcomes! If market returns are bad in the early years, a rising equity glidepath ensures that clients will dollar cost average into markets at cheaper and cheaper valuations; and if markets are good... well, clients won't have a lot to worry about in retirement anyway (except perhaps how much excess money will be left over at the end of their life).

Of course, the challenge to utilizing a rising equity glidepath strategy with clients is that many would obviously be concerned about having more equity exposure during their later retirement years. Yet the research shows that rising glidepaths can be so effective, they may actually lead to lower average equity exposure throughout retirement, even while obtaining more favorable outcomes. And ironically, it turns out that for those who do want to implement a rising equity glidepath, the best approach might actually be to explain it to clients as a bucket strategy in the first place!

Sequence Risk, Bucketing, And Retirement Success

In the 1990s, Bill Bengen published his first research on safe withdrawal rates, which made the fundamental point that it doesn't matter what a retiree's average returns are to determine if their plan will be successful; instead, it's necessary to look at the sequence in which those returns occur, as there are numerous historical scenarios where the long-term average may have been healthy but the sequence meant retirees had to withdraw far less. After all, it doesn't really matter if returns average out in the long run if ongoing retirement withdrawals mean there's no money left when the good returns finally arrive! Accordingly, the conclusion of the safe withdrawal rate research was that retirees should set their spending targets not based on average returns, but based upon the worst case scenarios that have occurred in history; if spending is low enough to survive all of those scenarios (whether due to unfavorable returns, or reasonable returns but an unfavorable sequence), it is presumed to be "safe."

Of course, in practice clients often notice the importance of return sequencing the moment a bear market occurs as they've begun down the retirement path, when they see their account balance fall precipitously and begin to worry - sometimes excessively so - about whether they need to adjust their spending or change their portfolio (or both). Accordingly, some advisors have adopted various forms of "bucket" strategies for clients over the years, designed to help clients get comfortable with ongoing volatility. For instance, if there's a "bucket" with 3 years of cash, clients may worry less about a short-term market decline. If there's a second pool of money with intermediate bonds for the subsequent few years, such that equities don't have to be touched for 8-10+ years in total, clients may be further soothed. If the bulk of ongoing expenses can be covered from direct cash flow sources, whether Social Security payments or a pension or annuitized income, it may be even easier to tolerate the market volatility.

However, the reality is that many of these types of bucket liquidation strategies often are more than just an exercise in mental accounting; having alternative fixed income sources to tap in the early years can help, both mentally and financially, to mitigate the danger of sequence risk. After all, the mathematical reality is that if there are no cash flows - i.e., there are no necessary withdrawals - then return sequencing is no longer an issue. In other words, as long as the retiree truly doesn't have to take any withdrawals from equities in the early years, and allows time for any early retirement bear markets to recover, the primary sequence risk of the portfolio/retirement scenario can be avoided!

Impact Of Rising Equity Glidepath On Retirement Income

While bucket approaches - from cash reserves to time-segmenting pools of money for use over time to partially annuitizing to reduce income needs in the early years - can be effective at reducing sequence risk, the reality is that strategies which disproportionately spend from fixed income assets and let equities grow will end out, after a number of years, with "distorted" asset allocations with a shrinking fixed income allocation and a rising percentage of equities. Of course, such outcomes can be averted by systematically replenishing the cash and fixed income buckets, but separate research has shown that approach can actually result in less retirement income, as the client simply ends out dragging too much in cash/low-yield assets as they're constantly replenished over time. In fact, as it turns out, the best outcomes are the ones where the short-term buckets are used to mitigate sequence risk in the early years but are not replenished - for instance, if the fixed income assets are used to partially annuitize the portfolio, with the remainder of the portfolio predominantly or fully invested in equities (and never reallocated back to bonds later), the results actually improve.

In fact, as Wade Pfau and I showed in recent research on partial annuitization, it turns out that much of the benefits being attributed to that bucketing strategy were not about the benefits of annuitization and having cash flows to avoid early withdrawals at all. Instead, the benefits of the strategy were actually primarily attributable simply to the asset allocation path that results from spending down fixed income assets in the early years and letting equity exposure rise, or what we labeled the "rising equity glidepath" throughout retirement. In other words, it was less about "not liquidating stocks in down markets" and more about "letting equity exposure grow over time" instead. Accordingly, in a new draft research paper we've just released, we delve further into this rising equity glidepath effect and find that in reality, increasing equity exposure throughout retirement can actually enhance retirement outcomes, and is so effective that the retiree can start more conservative and may even end out with less average equity exposure over their lifetime!

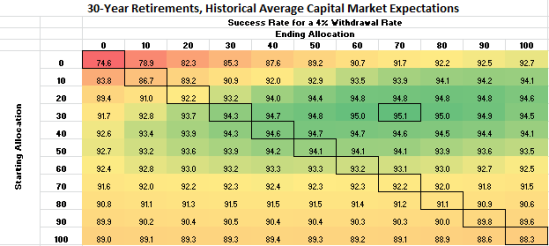

For instance, the chart below shows the probability of success using historical returns (average annual compound real growth rate of 6.5% for stocks and 2.4% for bonds) of various asset allocations based on a 4% withdrawal rate approach. In the chart, the starting equity exposure is on the vertical axis, and the ending allocation is on the horizontal axis. Thus, for instance, a portfolio that starts at 60% in equities and ends at 60% in equities (the intersection of the 60% row and column) has a 93.2% probability of success. However, a portfolio that starts at 30% in equities and finishes at 70% in equities actually has a higher (95.1%) probability of success, not to mention a lower average equity exposure through retirement (an average of only 50% in equities instead of 60%).

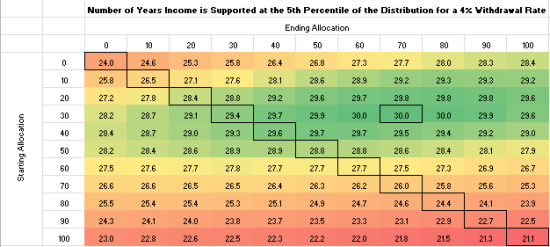

When viewing the magnitude of potential failures, we see a similar effect in the chart below. Looking at how many years the portfolio lasts at the 5th percentile (i.e., a "really bad" outcome scenario where we can get a sense of how bad the magnitude of failure is), the 30% --> 70% glidepath portfolio lasts for 30 years, while the constant 60% equity exposure portfolio is depleted in 27.7 years (or faster) in the 5% worst scenarios. (It's worth noting that historically, a 60/40 portfolio has never actually failed, implying some potential for time diversification or mean reversion that we did not specifically model in our Monte Carlo analysis for this research.)

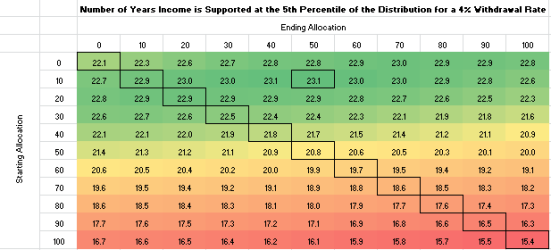

Of course, some will contend that today's environment will have diminished returns, even over the long run, relative to historical standards. Accordingly, the chart below shows the glidepath results with the return assumptions that Harold Evensky recommends for the popular MoneyGuidePro financial planning software package (arithmetic real returns of 5.5% for equities and 1.75% for bonds, which given their volatility result in geometric means of 3.4% and 1.5% respectively). Notably, these assumptions reflect both a lower overall return environment compared to historical averages, and also a reduced equity risk premium (i.e., the excess return of stocks over bonds is diminished).

Given the reduced return environment (and especially the reduced "bonus" for owning equities), all the scenarios face earlier failure points (the "best" is only 23.1 years at the 5th percentile!), and the optimal glidepath becomes even more conservative, starting at 10% and rising to only 50%. Nonetheless, in this environment the rising glidepath effect is still present; in fact, the conservative rising glidepath lasts almost 20% longer at the 5th percentile than the static 60/40 portfolio!

Practical Implications For Planners

From the financial planning perspective, these results may be somewhat surprising. In a world where the conventional wisdom is that retirees should reduce their equity exposure throughout retirement as their time horizon shortens, this research suggests that in reality, the ideal may actually be the exact opposite.

Yet viewed from the perspective of sequence risk, this result should not be surprising. After all, as shown previously in the May 2008 issue of The Kitces Report, outcomes for a 30-year retirement time horizon are driven heavily by the results over the first 15 years (i.e., the first half) of retirement. If the first half of retirement is good, the retiree is so far ahead that a subsequent bear market cannot threaten their retirement goal (though obviously, such a late-retirement decline will reduce the remaining legacy at death). Conversely, if the first half of retirement is bad (e.g., a retiree starting in the late 1920s or late 1960s or more recently the late 1990s), there is a danger that even if returns average out favorably through retirement, if the portfolio is depleted too severely by withdrawals and bad returns in the early years, there won't be enough (or any) money left for when the good returns finally arrive. And notably, the truly dire situations are not merely severe market crashes that occur shortly after retirement, but instead the extended periods of "merely mediocre" returns that last for more than a decade, which are far too long to "wait out" just using some cash and intermediate bond buckets.

In this context, the problem with the "traditional" approach of decreasing equity exposure through retirement becomes clear. If the retiree started in an environment like the late 1920s or late 1960s and decreases equity exposure systematically (e.g., by 1% to 2% per year), then by the time the good returns finally show up (about 15 years later) equity exposure will have been decreased so much that there simply won't be enough in equities to benefit when the good returns do show up. In other words, even if spending was conservative enough to survive the time period, selling equities throughout flat or declining markets amounts to liquidating while the market is down and not being able to participate in the recovery and the next big bull market whenever it finally arrives. Conversely, when the equity glidepath is rising and the retiree adds to equities throughout retirement (and/or especially in the first half of retirement), then by the time the market reaches a bottom and the next big bull market finally begins, equity exposure is greater and the retiree can participate even more!

Or viewed another way, the reality is simply that if market returns are poor throughout the first half of retirement, a rising equity glidepath is the equivalent of systematically dollar cost averaging into the market (with all the benefits that entails), while decreasing exposure amounts to reverse dollar cost averaging out of a bad market (with all the adverse results that apply). The strategy effectively becomes a way to ensure that clients are buying at favorable market valuations if they'll need to do so to make their retirement work. And notably, this implies that other valuation-based investment strategies may also have favorable outcomes (as discussed in the May 2009 issue of The Kitces Report); in fact, the reality may simply be that a rising equity glidepath is simple a way to ensure clients add to equities if valuations become cheap (i.e., returns are mediocre) through the first half of their retirement.

Of course, in a scenario where a retiree is following a rising equity glidepath, and it turns out market returns are good - and the client suddenly winds up with far more wealth than ever anticipated - there's always an option to change paths at that point, whether by bringing spending up or by taking equity risk off the table. Though technically they'll be so far ahead that a rising equity glidepath isn't a "risk" (i.e., even with a bear market, they're far enough ahead with few enough years remaining that there's no more failure risk), certainly some clients will decide that after a great bull market that changes their planning outlook and ability to achieve their goals, it may be prudent to get more conservative at that point. But for clients who go through a poor market in the early years, the rising equity glidepath becomes key to being able to sustain through the second half of retirement when the good returns finally arrive (in case the double-digit earnings yields on equities aren't enticing enough at that point!). In other words, the rising equity glidepath becomes "heads you win, tails you don't lose" (and in the latter scenarios, the client can change to whatever they want later instead).

Rising Glidepaths, Buckets, And Client Psychology

From the practical perspective, planners are no doubt wondering how to actually get older clients comfortable with the idea of increasing equities through retirement, given that many clients are so fearful (and likely would be even more frightened and negative about stocks if they actually were going through a poor decade of results, as so many are today). Yet it's worth noting from the research that: a) the average equity exposure is actually less than a static 60/40 portfolio; b) even results that just start conservative and end at 60% in equities end out better than those maintaining 60% in equities throughout (i.e., clients don't end with any more equity exposure than they would have had otherwise, they just start with less!); and c) for many clients, a rules-based approach like "just annually rebalance to a new equity exposure that increases by 1% per year" may actually be a more comfortable way to execute, because it's based on a systematic rule and doesn't require in-the-moment decisions that are difficult to execute in the midst of a scary market environment.

In other words, the glidepath approach can be implemented just like a "normal" rebalancing approach and done systematically... it's just that the asset allocation to which the client is rebalanced shifts systematically by a small amount every year. If the client is rebalancing annually anyway, there may not even be any impact on total transaction costs; it's just that the trades to buy/sell make be slightly larger or smaller in amount than they otherwise would have been. And as I've written previously, the math of rebalancing alone is sufficient to ensure clients don't liquidate materially from equities during a bear market, even without a separate cash reserve.

Ironically, though, perhaps the best way to handle the client psychology aspects of implementing a rising equity glidepath strategy is to frame it as a bucket strategy. As noted earlier, the research paper that Wade Pfau and I produced earlier this year on partial annuitization showed that much of the benefits attributed to the bucket strategy were simply a rising glidepath effect, and I have also previously noted that in truth many bucket strategies are actually just an asset allocation mirage given that they often result in the exact same allocation that would have occurred without the buckets. On the other hand, there's little doubt in practice that clients mentally respond better to bucket strategies; as a way to frame and explain the strategy, it can be highly effective, as long as the bucket implementation doesn't so distort the portfolio and the client's balance sheet that it turns out to be harmful (as can be the case for large cash reserves).

In other words, perhaps the bottom line is that while a rising equity glidepath may be a more effective portfolio solution for sustaining a client's retirement income, we simultaneously still need to do a better job in presenting, reporting, and explaining it in a bucket format, especially when implementing a rising equity exposure throughout retirement.

In the meantime, though, we've submitted the paper for consideration to the Journal of Financial Planning, it has been accepted for presentation at the FPA Experience Call for Papers next month, and you can see a draft copy of the research yourself on SSRN.

And of course, as always, we welcome your thoughts, criticism (constructive, please!) and other feedback below in the comments below!