Executive Summary

As financial advisers strive to communicate value and differentiate themselves in a competitive landscape, the SEC's new Marketing Rule has significantly reshaped the compliance obligations tied to how firms advertise and promote their services. Now, three years into its implementation, the rule has proven to be more than a technicality: it represents a foundational component of the SEC's regulatory framework. With several high-profile enforcement actions already announced, it's increasingly clear that the SEC considers Marketing Rule compliance a top-tier priority. The rule fundamentally redefines how firms communicate with prospects and clients, making it essential for advisers to engage directly with the rule's requirements rather than delegate them entirely to compliance departments.

In this article, Isaac Mamaysky, Partner of Potomac Law Group and Cofounder of QuantStreet Capital, explores the key takeaways from the SEC's enforcement of the Marketing Rule – and how advisory firms can implement their marketing strategies confidently without fear of regulatory action.

At its core, the Marketing Rule reinforces the general anti-fraud principles that underlie the Federal securities laws. These principles include ensuring that advertising is not misleading, material statements of fact can be substantiated, and all investment advice is presented in a way that is fair and balanced.. The rule also governs how performance results can be presented in advertisements and how advisers may use client testimonials and third-party endorsements.

However, in the years since the Marketing Rule's compliance date, the SEC's enforcement activity has also underscored the areas of greatest regulatory focus. Hypothetical performance – especially when shared via publicly accessible websites – has consistently triggered enforcement actions, highlighting concerns about misleading unsophisticated investors. Firms have been penalized for sharing backtested or model performance with general audiences without vetting the recipients. The SEC has also brought charges over unsubstantiated claims, misuse of third-party ratings without proper disclosure, and paid endorsements or testimonials lacking requisite transparency. Collectively, these actions reflect a broader regulatory theme: marketing practices must reflect not only technical compliance but also fair, honest, and substantiated communication consistent with investor protection goals.

Advisers can take several steps to assess and reinforce their marketing compliance. Reviewing the Marketing Rule itself – surprisingly accessible at under 3,500 words – can help clarify its intent and applicability. Updating compliance manuals to reflect the new rule, rather than legacy advertising and solicitation guidance, is essential. From there, a detailed checklist covering definitions, prohibited practices, disclosures, performance standards, and documentation can help ensure policies are comprehensive and current. Testing those policies against hypothetical scenarios – such as athlete endorsements, mass mailings of hypothetical performance, or adviser-requested online reviews – can further refine understanding and reveal implementation gaps.

Ultimately, the key point is that the Marketing Rule is now firmly entrenched in the compliance expectations governing advisory firms' external communications. Advisers who approach the rule not as a compliance formality but as a guidepost for transparency and professionalism will be better positioned to communicate effectively, avoid regulatory pitfalls, and strengthen client trust. By aligning marketing practices with both the letter and spirit of the rule, advisers can elevate their messaging and reinforce the integrity at the heart of every great client relationship!

I'll be the first to acknowledge that compliance can be complicated, filled with technical rules, detailed regulations, SEC FAQs and Risk Alerts, and lengthy internal compliance manuals. These materials can be challenging, even for the most diligent firms.

Advisers often navigate this complexity by delineating between the critical rules needed to keep top of mind and the more technical ones that can be left to the firm's compliance teams. Not to pick on the humble Form ADV, but that annual filing obligation isn't something most advisers need to think about on a daily basis. They provide input to their compliance team, then rely on them to safely handle the rest before signing off and filing the document.

By contrast, the anti-fraud rules are widely recognized as foundational to the regulatory landscape. Advisers studied them when preparing for the Series 65, they're front-and-center in most compliance manuals, and they form the big picture themes underlying many other SEC regulations.

So, three years ago, when the SEC's new Marketing Rule made waves in the long-established regulatory landscape, advisers had to decide which category it belonged in: essential rule or compliance technicality?

Since the Marketing Rule went into effect, the SEC has identified it as an examination priority and issued risk alerts warning advisers of enforcement actions for noncompliance. Even more tellingly, the SEC has repeatedly brought charges against advisers for Marketing Rule violations; as the saying goes, actions speak louder than words. Taken together, these developments make it clear that the new rule falls firmly into the category of critical, top-of-mind compliance policies.

Inextricably linked to adviser communications, the Marketing Rule governs the language we use when speaking with both prospects and clients. Which means the rule has significant and very practical implications for how we run our firms and talk about our services. It's not just a compliance formality, but rather the lens through which the SEC scrutinizes many of our emails, websites, pitch decks, and other public-facing materials.

To understand why the Marketing Rule matters, it will be helpful to consider SEC enforcement trends over the past three years, some best practices for Marketing Rule compliance, and some hypothetical case studies that we can use to test our policies. Before getting there, though, a quick look at the core requirements of the Marketing Rule itself can set the stage with helpful context.

A Working Summary Of The Rule

While many advisers are generally familiar with the Marketing Rule, a broad overview of its key requirements will establish a shared foundation for understanding how it applies in practice.

Defining "Advertisement"

The Marketing Rule does not apply to every statement made by an investment adviser. Rather, it applies only to "advertisements". So, the first step is to determine whether the statement in question is regulated by the rule at all. Under the Marketing Rule, an "advertisement" is:

- Any communication an adviser makes to more than one person – or even to one person if the communication includes hypothetical performance – that offers investment advisory services, including new services to existing clients.

- Any endorsement or testimonial for which an adviser provides compensation is an advertisement, even if made to a single person.

General Prohibitions

The Marketing Rule begins with seven General Prohibitions, which reflect the historical anti-fraud principles of the securities laws. An advertisement may not:

- Include an untrue statement of material fact or omit a material fact necessary to make a statement not misleading;

- Make a material statement of fact that cannot be easily substantiated;

- Provide information that would cause an untrue or misleading inference about the investment adviser;

- Discuss benefits to the client of the investment adviser's services without discussing risks;

- Reference the adviser's specific investment advice in a manner that is not fair and balanced;

- Include or exclude performance results in a way that is not fair and balanced; or

- Mislead in any other way.

Testimonials And Endorsements

In a significant change from the pre-Marketing Rule regulatory landscape, the SEC now allows "testimonials" (given by current clients) and "endorsements" (given by non-clients). If an adviser pays for a testimonial or endorsement, it must have a written agreement with the promoter (i.e., the individual giving the testimonial or endorsement) memorializing the terms of the relationship, and the promoter cannot be an ineligible person or bad actor. Also, to use testimonials and endorsements in advertisements, regardless of whether the promoter has been paid, advisers must provide two types of disclosures:

- The first set of disclosures must be "clear and prominent" – which, the SEC explains, means "the disclosures must be at least as prominent as the testimonial or endorsement" and included "within the testimonial or endorsement" -- and must address the following questions:

- Is this a testimonial given by a current client, or an endorsement given by a non-client?

- Was compensation provided for the testimonial or endorsement?

- What is the overview of material conflicts of interest on the part of the promoter?

- The second set of disclosures does not need to be clear and prominent:

- What is the compensation arrangement, if any, between the adviser and promoter?

- What are the details of the conflicts of interest on the part of the promoter resulting from the relationship with the adviser or any compensation paid for the testimonial or endorsement?

Advisers don't have to deliver these disclosures directly, but they must have a reasonable basis to believe that the promoter delivered them as required by the rule. As already noted, advisers must have a written agreement with any compensated promoter, which is a good place to contractually bind promoters to share the required disclosures.

Third-Party Ratings

The new rule allows advisers to use third-party ratings in advertisements (e.g., "We were named a top 10 adviser in the tristate area"), but this is subject to certain conditions:

- The adviser must reasonably believe, following due diligence, that the rating platform made it equally easy for contributors to submit a negative or positive review, and the rating wasn't designed to create a predetermined result; and

- Advertisements must "clearly and prominently" disclose:

- The date of the rating and the time period on which the rating is based;

- The identity of the entity that issued the rating; and

- If applicable, that the adviser paid to use or obtain the rating.

Performance

In the Adopting Release for the Marketing Rule, the SEC explained its concern that performance advertising is especially likely to mislead investors. To address this risk, the rule establishes various requirements for advertisements that include performance:

Gross and Net Performance. When an advertisement includes gross performance, it must include equally-prominent net performance (i.e., performance net of the adviser's management fees).

Performance Time Periods. Advertisements that include performance results for a particular time period must include equally prominent performance results for the past one-, five-, and ten-year periods.

Related Performance. An advertisement cannot include any performance of a related portfolio unless it includes the performance of all related portfolios (i.e., any portfolio with similar investment policies, objectives, and strategies as those being offered in the advertisement).

Extracted Performance. If an advertisement includes "extracted performance" showing just a subset of investments in the portfolio, it must either provide the performance of the entire portfolio or offer to provide it promptly.

Hypothetical Performance. Advertisements can only include hypothetical performance (e.g., the performance of models, backtests, and targets) if the adviser:

- Believes the hypothetical performance is relevant to the financial situation and investment objectives of the intended audience;

- Explains the criteria and assumptions on which the hypothetical performance is based; and

- Discloses the risks and limitations of relying on hypothetical performance.

Predecessor Performance. The Marketing Rule only allows advertisements to include the adviser's performance from a past firm or previous team if they pass the following multifactor test:

- The individuals responsible for that performance manage accounts for the advertising adviser;

- The predecessor accounts are similar to the adviser's current accounts;

- Every similarly managed predecessor account is included in the performance results; and

- The advertisement prominently discloses that the performance results are from accounts that were managed at another firm.

SEC Actions For Marketing Rule Violations

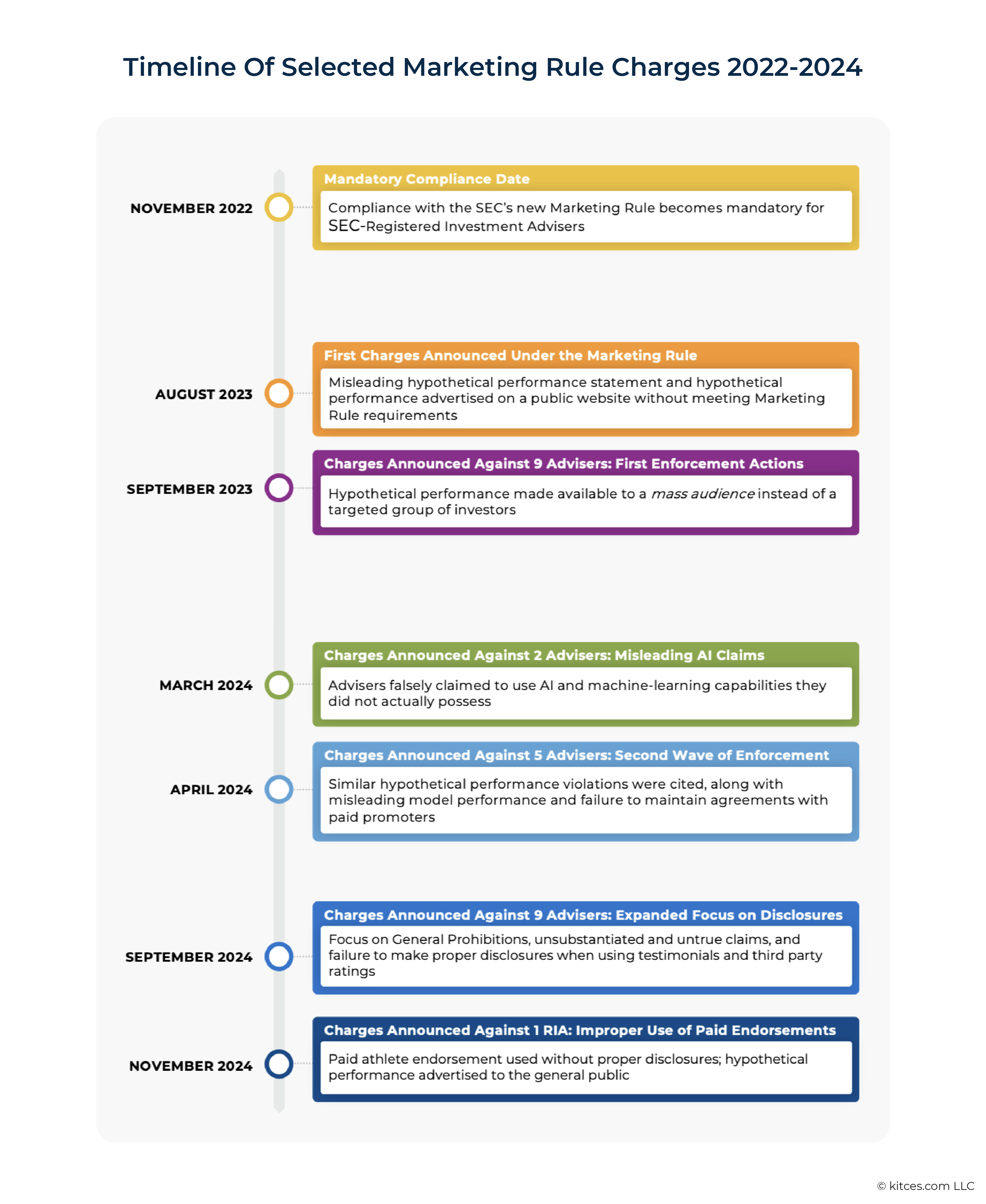

Compliance with the Marketing Rule became mandatory on November 4, 2022. As we mark the third anniversary of the rule, the SEC has announced several enforcement actions concerning Marketing Rule violations. While certainly not the only ones, a few sets of these actions drew widespread attention following SEC press releases.

August 2023. About nine months after the mandatory compliance date, the SEC announced its first charges for Marketing Rule violations. The SEC alleged that an adviser made misleading statements about hypothetical performance and advertised hypothetical performance on its website without following the Marketing Rule's requirements.

September 2023. A month after that, the SEC announced charges against nine advisers for advertising hypothetical performance on their websites. These nine firms were subject to SEC charges for making hypothetical performance available to a mass audience, rather than a targeted group of investors for whom the advisers reasonably believed the hypothetical performance was relevant.

March 2024. About six months later, the SEC announced charges against two investment advisers for making false statements about their use of artificial intelligence by claiming that they had AI and machine-learning capabilities that they did not actually have.

April 2024. A month later, the SEC announced charges against five more advisers for advertising hypothetical performance to the general public. Once again, these advisers included hypothetical performance on their websites.

The SEC also charged one of the firms with violating other Marketing Rule requirements, including "making false and misleading statements in advertisements, advertising misleading model performance, being unable to substantiate performance shown in its advertisements, and failing to enter into written agreements with people it compensated for endorsements."

September 2024. Five months later, the SEC announced charges against nine more investment advisers for making untrue or unsubstantiated claims in advertisements, using testimonials, endorsements, and third-party ratings without the required disclosures. More specifically, the SEC alleged:

- Two firms advertised untrue statements about third-party ratings;

- One firm falsely claimed it was a member of an organization that didn't exist;

- Four firms claimed that they provided "conflict-free advisory services", but the firms couldn't substantiate this claim;

- One firm was unable to substantiate statements about an award received by a firm principal;

- One firm advertised two "testimonials", but neither actually came from current clients, and it also advertised endorsements that did not disclose that the endorser was a paid non-client of the firm; and

- Four firms used third-party ratings without disclosing the dates on which the ratings were given or the periods of time upon which the ratings were based.

November 2024. Fast-forwarding another two months, the SEC announced charges against another RIA for using paid athlete endorsements without the required disclosures and for advertising hypothetical performance to the general public on its website.

While the SEC has brought other Marketing Rule charges, these examples reflect some of the notable actions announced to date.

Key Themes Of SEC Charges

Taking these highly publicized SEC charges together, we see certain enforcement trends. The SEC has focused its attention on hypothetical performance, the Marketing Rule's General Prohibitions, testimonials and endorsements, and third-party ratings. Let's consider the SEC's rationale for each of these apparent enforcement priorities.

Enforcement Trend 1: Hypothetical Performance

One of the simplest and clearest takeaways from the enforcement trends is that hypothetical performance should never appear on a publicly accessible website. The Marketing Rule defines hypothetical performance as "performance results that were not actually achieved by any portfolio of the investment adviser," including "model performance, backtested performance, and targeted or projected performance."

In the Adopting Release to the new rule, the SEC explained that it is particularly concerned with these types of performance results because of the risk that they can unduly influence unsophisticated investors:

[W]e believe that such presentations in advertisements pose a high risk of misleading investors since, in many cases, they may be readily optimized through hindsight. Moreover, the absence of an actual investor or, in some cases, actual money underlying hypothetical performance raises the risk of a misleading advertisement, because such performance does not reflect actual losses or other real-world consequences if an adviser makes a bad investment or takes on excessive risk.

Simply put, hindsight is 20-20, but foresight is far from it. This is the potential problem with hypothetical performance and the reason it can unduly influence investors. The general idea is that hypothetical performance tends to be most appropriate for sophisticated investors who are experienced, fully appreciate its limitations, and understand the significant risk that actual performance – involving real dollars and unknown future events – will substantially deviate from hypothetical performance, which can be optimized and modified based on past events and hypothetical dollars.

Enforcement Trend 2: Honest, Substantiated Statements

The SEC has also been focused on enforcing the Marketing Rule's General Prohibitions, which, it explained in the Adopting Release, "are drawn from historic anti-fraud principles under the Federal securities laws." Going beyond investment adviser oversight, these are among the key themes of the Federal securities laws – they reflect the goals and rationale underlying much of the SEC regulatory scheme.

This context can help us appreciate why the General Prohibitions include requirements that an advertisement may not contain untrue or misleading statements, provide information that can't be substantiated, or be materially misleading in any other way. Their fundamental goal is to further the SEC's very purpose of protecting investors and facilitating trust in the securities markets.

Applying this foundational principle of the securities laws, advisers must be honest in their communications, cannot make statements that lead to misleading inferences, and must be able to substantiate everything they say. In the Adopting Release, the SEC warns: "If an adviser is unable to substantiate the material claims of fact made in an advertisement when the Commission demands it, we will presume that the adviser did not have a reasonable basis for its belief."

As the compliance mantra goes: If you can't prove it, don't say it.

Enforcement Trend 3: Testimonials And Endorsements

Another key enforcement area for the SEC has been noncompliant testimonials and endorsements. Many advisers remember that testimonials and endorsements were historically banned; before the new rule, this was a basic principle of investment adviser regulation.

The prohibition was based on the SEC's long-held belief that these types of reviews could mislead or unduly influence investors. But times have changed. Many of us won't set foot in a new restaurant without reading its online reviews first, never mind the far more important decision of choosing a financial adviser. We increasingly rely on customer feedback when making purchasing decisions.

As the SEC explained in the Adopting Release:

Numerous commenters supported the proposed expansion from the current advertising rule to permit advisers to include testimonials and endorsements in advertisements [because] consumer preferences have shifted to rely increasingly on third-party resources to inform purchasing decisions. Other commenters opposed permitting any testimonials or endorsements, paid or unpaid, in adviser advertisements[, arguing that] permitting advisers to advertise paid testimonials and endorsements would increase puffery and cause a "race to the bottom" for advisers seeking paid endorsements.

Ultimately, the SEC can't ignore the modern shift in consumer sentiment; consumers depend on reviews to make informed purchasing decisions, and the securities laws have to keep up. Recognizing this, the SEC has allowed testimonials and endorsements, subject to important compliance guardrails. When consumers have basic information about the promoter's relationship with the firm, their compensation, and potential conflicts of interest, the advertisement is less likely to be unduly misleading.

Thus, the basic principles here are as follows: If someone is speaking for you, say who they are and why they might be biased. Along the same lines, if you're paying for praise, then disclose the pay.

Enforcement Trend 4: Third-Party Ratings

To round out the enforcement trends, the SEC has also scrutinized the use of third-party ratings in advertisements. In the Adopting Release, the SEC noted concerns that advisers "will be incentivized to purchase only positive third-party ratings and aggressively market them to mislead investors." The Commission ultimately rejected a ban on ratings but emphasized that due diligence and disclosure requirements – "in conjunction with the [Marketing Rule's] General Prohibitions" – are designed to prevent that very outcome.

As discussed above, advisers must have a reasonable basis to believe the rating platform provides a fair and balanced process, making it equally easy for contributors to provide both favorable and unfavorable feedback. Advertisements must also include clear and prominent disclosures identifying the rating entity, the date and time period covered, and whether compensation was paid for the rating.

Yet the SEC cautioned that even perfect disclosures do not excuse a misleading rating. As the Adopting Release explains: "disclosures would not cure a rating that could otherwise be false or misleading under the final rule's general prohibitions or under the general anti-fraud provisions of the Federal securities laws." For example, an advertisement would be misleading if it cites a recent rating based on a part of the adviser's business that has since materially changed, or if it touts a "top adviser" ranking that is based solely on assets under management, which may have little to do with the quality of the firm's investment advice.

The key takeaway is this: If you use a third-party rating, make sure the rating process was fair, the picture the rating paints is honest, and any payment for the rating is disclosed.

The Limitations Of Enforcement Trends

When discussing these enforcement trends, there's a risk of implying that the SEC's focus is limited to these specific areas. However, this overview is not intended to suggest that the SEC will overlook other aspects of the Marketing Rule. Future charges will almost certainly address different elements of Marketing Rule compliance. Nevertheless, advisers can use these current enforcement trends to evaluate their own policies and procedures.

Checking Firm Policies

Advisers can take several practical steps to strengthen compliance with the Marketing Rule in their own practices. To avoid being on the receiving end of an SEC action, the following roadmap can be helpful:

- Review the current Marketing Rule and update older compliance policies that still rely on the superseded provisions;

- Double-check existing compliance policies using the checklist provided below;

- Test firm policies and understanding against fact patterns inspired by SEC enforcement trends and other Marketing Rule requirements.

Each of these steps is discussed in more depth in the following sections. Taken together, these steps can help ensure that firm communication and marketing practices stay aligned with regulatory expectations.

Reading The Rule And Updating Old Compliance Policies

I know, I know – I'm asking you to read the rule itself, but let me explain. Unlike certain lengthier and much more complex rules, the entire Marketing Rule is just under 3,500 words – shorter than many Nerd's Eye View articles!

It's the kind of rule that's fairly easy to understand because it concerns adviser communications with prospects and clients; the primary context needed to grasp the Marketing Rule is simply knowing how a firm speaks with its stakeholders. To be sure, it's not exactly light reading, but it's also quite approachable.

As a starting point, advisers can review the rule and confirm that their compliance manuals reflect its current provisions rather than the requirements of the old advertising and cash solicitation rules.

A Checklist To Ensure Compliance Policies Meet The Mark

Once advisers have read the rule and gained a general understanding of its requirements, they can use the following checklist to assess their compliance policies. While all parts of the rule are important and may be subject to future SEC actions, the focus areas of recent enforcement trends are shown in bold.

- Does the policy define the term "advertisement" and thus frame which communications it applies to?

- Does the policy explain the General Prohibitions, which are the key anti-fraud rules of the Federal securities laws? Does it cover:

- Making untrue statements or omitting facts?

- Making unsubstantiated claims?

- Raising misleading inferences?

- Discussing benefits without discussing risks?

- Referencing specific advice in a manner that isn't fair and balanced?

- Including or excluding performance results in a manner that's not fair and balanced?

- Being misleading in any other way?

- Does the policy cover the required disclosures that need to accompany testimonials and endorsements?

- Does it require clear and prominent disclosure about whether the testimonial is given by a current client, or the endorsement is given by a non-client?

- Does it require clear and prominent disclosure that compensation was provided for the testimonial or endorsement (if applicable)?

- Does it require clear and prominent disclosure of material conflicts of interest on the part of the promoter?

- Does it require disclosure of details about the compensation arrangement with the promoter and conflicts of interest?

- Does the policy require a written contract with paid promoters? Does it prohibit testimonials and endorsement by ineligible parties and bad actors?

- As to third-party ratings, does the policy require:

- Clear and prominent disclosures

- regarding the date of the rating and the time period on which it's based?

- the identity of the entity that issued the rating?

- whether the adviser paid to use or obtain the rating (if applicable)?

- The adviser to reasonably believe, following due diligence, that the rating platform made it equally easy for contributors to submit a negative or positive review, and that the rating wasn't designed to create a predetermined result?

- Clear and prominent disclosures

- Regarding performance advertising, does the policy ensure that:

- Hypothetical performance is only shared with a limited audience when the adviser believes it is relevant to the recipients' financial situations and investment objectives?

- Net performance is included whenever an advertisement includes gross performance?

- One-, five-, and ten-year performance time periods are included whenever any isolated performance time periods are included?

- The performance of all related portfolios is included whenever an advertisement includes the results of a particular portfolio?

- The adviser offers to provide the entire portfolio's performance whenever an advertisement includes extracted performance from a subsection of the portfolio?

- Predecessor performance is only used when the Marketing Rule's multifactor test (explained in the above summary of the rule) is met?

- Does the policy require pre-approval of advertisements by the compliance team?

- Does the policy address the adviser's recordkeeping obligations for advertisements, including retaining copies of all advertisements, related disclosures, and documentation substantiating performance claims and statements of fact?

Some Hypothetical Scenarios

After reviewing the Marketing Rule and confirming that compliance policies reflect the new rule rather than the old ones (using the above checklist as a review guide), advisers can test their understanding by working through hypothetical fact patterns.

Each scenario below presents a short case followed by its resolution, illustrating how the Marketing Rule applies in common real-world situations.

Hypothetical Performance

Facts: An adviser meets a prospective client at a local business networking event. They exchange contact information. After returning home, the adviser wants to send the prospect a set of slides including backtested, hypothetical performance. Is this allowed?

Resolution: Maybe. The adviser must reasonably believe that the hypothetical performance is relevant to the financial situation and investment objectives of the prospect. The slides must also explain the criteria and assumptions on which the hypothetical performance is based and disclose the risks and limitations of relying on hypothetical performance. Note that this communication is an "advertisement" and therefore subject to the Marketing Rule, despite only being sent to one person, because it includes hypothetical performance.

----------------

Facts: An adviser speaks about financial planning at a local chamber of commerce event. The attendees include established local businesspeople, students, retirees, and job seekers, among others. The adviser invites the attendees to provide their email addresses to receive more information about the firm. Around 50 people sign up. The adviser plans to send all of them slides, including backtested, hypothetical performance. Is this allowed?

Resolution: No. Because the communication would go to a broad and diverse audience, the adviser cannot reasonably believe that the hypothetical performance is relevant to each recipient's financial situation and investment objectives.

Testimonials And Endorsements

Facts: An adviser has a client who is a well-known athlete. As the relationship deepens, the adviser asks the athlete to appear in an advertisement including a quote praising the adviser's services and commitment to clients. "Of course," the adviser says, "I'll gladly pay you for doing this." Is this allowed?

Resolution: Maybe. When an advertisement includes a testimonial, it must include a clear and prominent disclosure explaining whether it was given by a current client, whether compensation was paid for it (if applicable), and any conflicts of interest arising from the adviser's relationship with the promoter. The advertisement must also include more specific disclosures about compensation and conflict of interest details. Finally, since the athlete is being paid, the Marketing Rule requires a written agreement to memorialize the relationship and to confirm that the athlete is not an ineligible person or bad actor.

----------------

Facts: An adviser hires a new marketing firm that doesn't typically work in the financial services space. The marketing strategist proposes a series of online banner ads saying: "Want to work with the best financial adviser in town? Call for a free consultation!" Is this allowed?

Resolution: No. Advisers are prohibited from making unsubstantiated or unprovable claims in advertisements.

Performance Advertising

Facts: An adviser writes an article for distribution to their mailing list about the performance of one particular investment in the adviser's portfolio. The article includes an overview of the adviser's other recommendations and the performance of its overall portfolio. Is this allowed?

Resolution: Yes. If an advertisement includes extracted performance, then it must also include the performance of the rest of the portfolio (or offer to provide it promptly). This assumes, of course, that the presentation is also fair, balanced, and not misleading. Also, if an advertisement includes performance results for a particular time period, then it must include equally prominent performance results for the past one-, five-, and ten-year periods.

Definition Of Advertisement

Facts: Without the adviser's involvement, a search engine creates a business listing and allows visitors to rate the adviser. Over time, the adviser's listing accumulates 50 reviews with a 4.5-star average. The adviser never encourages clients to leave reviews, does not engage with the reviews, and does not distribute them or refer to them. Is this allowed?

Resolution: Yes. The Marketing Rule applies to "Advertisements," which are communications made by the adviser to more than one person offering the adviser's services (or to one or more people if the communication includes hypothetical performance). When an adviser does not initiate or engage with online reviews, those reviews are likely not a communication of the adviser at all.

Definition Of Advertisement, Testimonials And Endorsements, General Prohibition

Facts: An adviser sets up a business listing on a prominent search engine. The adviser actively encourages clients to contribute reviews, and then comments on the reviews they don't agree with. The adviser also sends a link to the review page to prospective clients, despite knowing that some of the reviews have false information. The business listing doesn't include any particular disclosures or disclaimers, nor do any of the individual reviews. Is this allowed?

Resolution: No. If an adviser sets up a business listing, encourages clients to post reviews, and comments on those reviews, then the listing may be considered a communication of the adviser because they have adopted or become entangled in the content. In this case, the reviews would need to have the required disclosures for testimonials and endorsements, which they likely do not. Also, if some of the reviews contain false information and the adviser sends out the link anyway, the action could be considered a deceptive practice in violation of the Marketing Rule's General Prohibitions.

General Prohibitions

Facts: An adviser puts out a white paper explaining the benefits of the adviser's services. It explores the historical strengths of the adviser's advice, explains why the adviser's services are useful to high-net-worth clients, and notes the large number of clients who have been with the adviser for a decade or more. The white paper doesn't discuss past missteps (of which there were a few), clients who have moved on to other advisers, or other negative outcomes. Is this allowed?

Resolution: No. The Marketing Rule's General Prohibitions do not allow advisers to advertise the benefits of their services without discussing the risks. Also, advisers cannot advertise specific investment advice in a manner that isn't fair and balanced.

Now that the third anniversary of the Marketing Rule has arrived, it may be fair to say that the rule is no longer 'new' but has become part of the core regulatory landscape for investment advisers.

The SEC has made clear that compliance with the rule is an enforcement priority, and it's one that advisers must keep top of mind because it governs the very words used when communicating with prospects and clients. Advisers who treat the Marketing Rule as a framework for transparent and compliant communication will be best positioned not only to withstand SEC scrutiny, but also to strengthen the trust, clarity, and professionalism that define truly great client relationships.

Leave a Reply