Executive Summary

For millions of Americans who are self-employed, between jobs, or retired before reaching Medicare eligibility at age 65, the primary source of health insurance is the Federal or state Marketplace exchanges created by the Affordable Care Act (ACA). Many of these individuals and families rely on the Premium Tax Credit (PTC) to reduce the cost of their coverage: By limiting the out-of-pocket premium cost to a certain percentage of household income, the PTC effectively subsidizes Marketplace-purchased plans – which are often significantly more expensive than employer-sponsored or government-provided coverage.

From 2021 through 2025, COVID-era legislation temporarily 'enhanced' the PTC by reducing the maximum out-of-pocket limits on insurance premiums and making the credit available to households with income higher than 400% of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL), a group who had previously been disallowed from receiving the PTC. However, Congress allowed the enhanced credit to expire at the end of 2025, reverting the PTC rules back to their pre-2021 version. Which means that households still eligible for the PTC will see a reduction in their credit amount – leading to moderate increases in their out-of-pocket premium payments in 2026 – while those with income over 400% of FPL will be disqualified from receiving the PTC at all, resulting in even sharper cost increases for Marketplace coverage.

The actual amounts of these premium increases will depend on household size and the cost of the underlying insurance plan. Single people with plans that cover only themselves may see modest increases; however, larger families or older couples with more expensive coverage could see their premiums rise by more than $1,000 per month. And because the 400%-of-FPL threshold is a hard cutoff for the PTC, even $1 of income beyond that amount can result in thousands of dollars of additional premiums – all of which must be repaid to the IRS if they were originally paid out as advance premium subsidies.

For households with Marketplace coverage, then, it can be extremely beneficial to keep income under 400% of FPL – $62,600 for a single person, $84,600 for a couple, or $128,600 for a family of four in 2026 – when it's possible to do so. For people who are still working, contributions to pre-tax retirement accounts such as traditional IRAs and 401(k) plans, as well as HSAs and FSAs, can help reduce AGI, which is used to calculate household income for PTC purposes. Self-employed individuals may also have flexibility through the timing of business income and expenses. And those who are retired or between jobs can manage their income by adjusting the mix of pre-tax, Roth, and taxable account distributions, even when traditional tax planning strategies might otherwise favor drawing from pre-tax accounts.

The key point is that even though health insurance premium increases are coming to nearly everyone on Marketplace plans in 2026, the most severe increases – particularly for families just over the 400%-of-FPL threshold, for whom losing the PTC could significantly strain cash flow – can often be mitigated through careful tax planning to reduce AGI via income exclusions and above-the-line deductions. And even for the many families who have already enrolled in Marketplace plans for 2026, income changes made during the year can be updated on their insurance application to re-calculate their PTC for the remainder of the year – meaning it's not too late to put strategies into place to reduce the pain of higher insurance premiums in the year ahead!

The health insurance system in the U.S., which intermediates access to health care for nearly all Americans, consists of a patchwork of public and private insurers that offer coverage to individuals based on their age, income level, and/or employment status. The largest number of Americans by far (nearly 50% of the total population, according to research by the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF)) get their health insurance coverage through an employer – either their own, their spouse's, or a parent's. An additional 37% have government-provided coverage such as Medicare (primarily for individuals age 65 or older), Medicaid (for children and adults with low income), or military health insurance plans.

But while employer and government-provided health insurance combine to cover a large majority of Americans, there is still a substantial minority who don't have access to either. Some are self-employed, others work for employers that are too small to offer their own health insurance coverage, others experience gaps between employers, and still others retire before age 65 when they become eligible for Medicare.

Whatever the reason, individuals who don't qualify for insurance through employer or government channels must rely on the individual insurance market for their health insurance coverage. And most of the time, these individuals get their health insurance through the Federal or their state's insurance exchange as created by the Affordable Care Act (ACA) of 2010.

But while individual health insurance can provide coverage for those who fall through the gaps of employer- or government-provided insurance, they also to be much more expensive for the insured. Employer and government plans benefit from group pricing due to their scale, and are also often subsidized by the employer or government program providing the coverage. Thus, a family plan that someone might pay $500 per month for as an employee could cost $1,000 per month or more on the individual insurance market.

Prior to the ACA, the costs for individual insurance were so high that a large number of people – over 15% of the population – simply went uninsured, preferring to take their chances on not incurring a significant health care expense. To address this, the ACA created a subsidy for certain Marketplace plans, which took the form of a tax credit: the Premium Tax Credit (PTC). The PTC serves to directly reduce monthly health insurance premiums for eligible households by being credited to the premium payment itself, reducing insurance premiums in some cases all the way to $0.

From 2021 through 2025, the PTC has been 'enhanced' by COVID-era legislation that increased the amount of the subsidy it provides and made it more widely available, particularly to households whose income had previously been too high to qualify. However, the enhanced PTC is scheduled to expire at the end of 2025, meaning that people with Marketplace insurance coverage will see their premiums increase in 2026 – in many cases, to more than double their 2025 cost.

This shift has major implications for advisors working with pre-65 retirees, self-employed clients, and anyone using Marketplace plans. But while many of these individuals will experience higher premiums after the expiration of the 'enhanced' PTC, careful planning of income and deductions can help to reduce the financial blow of the enhancement's expiration.

How The Premium Tax Credit (PTC) Works

Conceptually, the Premium Tax Credit (PTC) limits the amount of an individual's out-of-pocket health insurance premiums so they won't exceed a certain percentage of the insured person's household income. The percentages move on a sliding scale based on household income: The higher the income, the higher the percentage of that income the individual is required to contribute toward their premium costs. The PTC, then, effectively pays for the remaining health insurance premium that exceeds the amount the individual is required to contribute themselves.

Unlike most tax credits, the PTC is paid throughout the year instead of being claimed when filing a tax return after the end of the year. Each individual's PTC directly reduces the monthly premiums paid on their insurance coverage. For instance, if a taxpayer's Marketplace-purchased health insurance costs $1,000 per month and they are eligible for a total (full-year) PTC of $6,000, then their actual monthly premium payment will be $1,000 – ($6,000 ÷ 12) = $500.

To be eligible for the PTC, individuals must purchase their health insurance through a Federal or state insurance exchange. Additionally, they cannot be enrolled in – or eligible for – any coverage provided by their or their spouse's employer if the cost of that coverage doesn't exceed a certain percentage of household income (9.96% in 2026). For instance, if an individual has employer coverage and if adding their spouse would cost 10% of their household income, then the spouse's coverage is deemed 'unaffordable', making the spouse eligible for the PTC if they enroll in a Marketplace plan for their own coverage.

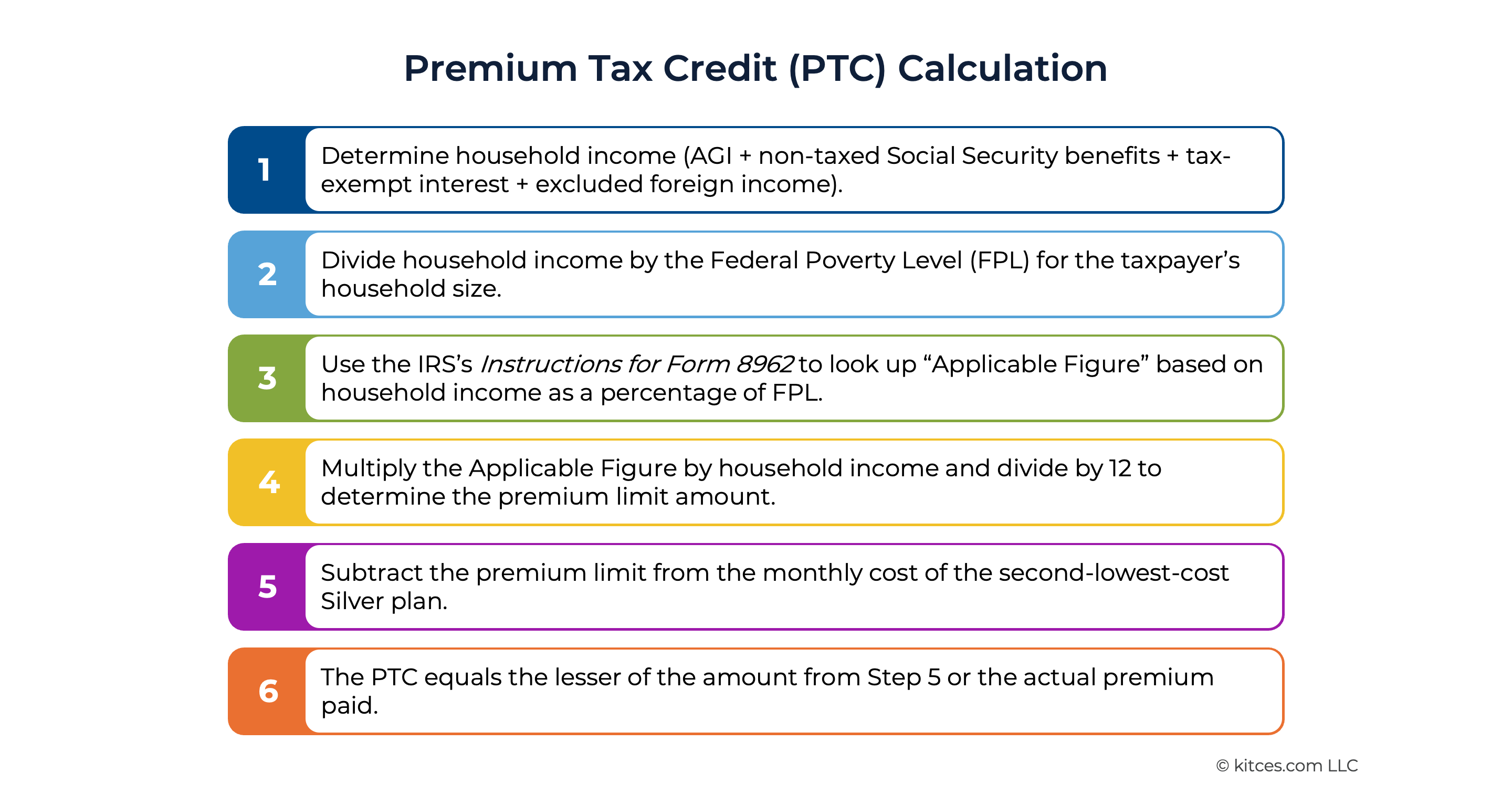

Calculating The PTC

The PTC calculation is complex, and while financial advisors don't necessarily need to know all the calculation details themselves – there are online calculators that can provide a quick estimate – it can be helpful to understand the calculation at a high level and recognize the important factors that determine an individual's PTC, in order to plan for how to increase the PTC they might be eligible for.

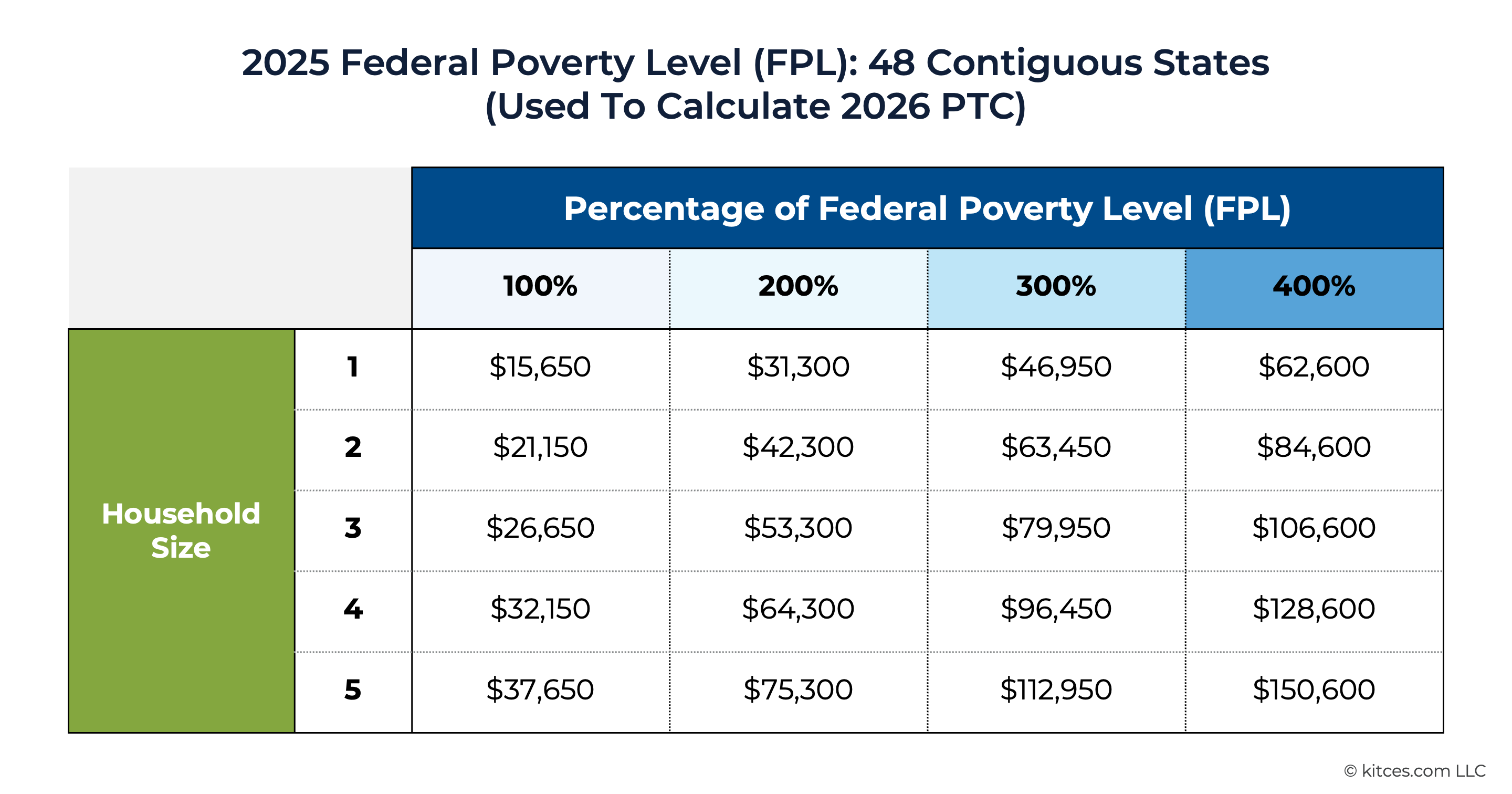

The PTC is based on household income in relation to the prior year's Federal Poverty Guidelines, more commonly known as the Federal Poverty Level (FPL). FPLs are listed by the number of people in a household: The more people who live in one household, the higher the FPL for that household. The 48 contiguous states all share the same FPL table, while Alaska and Hawai'i each have their own separate tables due to the unique cost of living circumstances in those states.

For PTC purposes, household members include the taxpayer, spouse, and any dependents claimed on the tax return. Household income is defined as Modified Adjusted Gross Income (MAGI), which equals AGI plus any amount of untaxed Social Security benefits, tax-free interest (e.g., from municipal bonds), and excluded foreign income.

To calculate an individual's PTC, their household income is first calculated as a percentage of the FPL. That percentage corresponds to an "Applicable Figure" – the limit on the taxpayer's out-of-pocket premiums as a percentage of their household income – published by the IRS each year in their Instructions for Form 8962. The Applicable Figure is multiplied by household income and divided by 12 to determine the individual's maximum out-of-pocket premium. That number is then subtracted from the cost of a standard "benchmark" Marketplace insurance plan (defined as the second-lowest-cost Silver plan available in the taxpayer's area) to come up with the taxpayer's PTC.

If the PTC is equal to or higher than the individual's actual monthly insurance premium, then there is no out-of-pocket cost for the insurance (there is no refund for additional PTC beyond the actual amount of premiums paid). If the insurance premium is higher than the PTC, then the taxpayer pays the difference as their out-of-pocket amount.

Impact Of Expiring 'Enhanced' Credit On Health Insurance Premiums

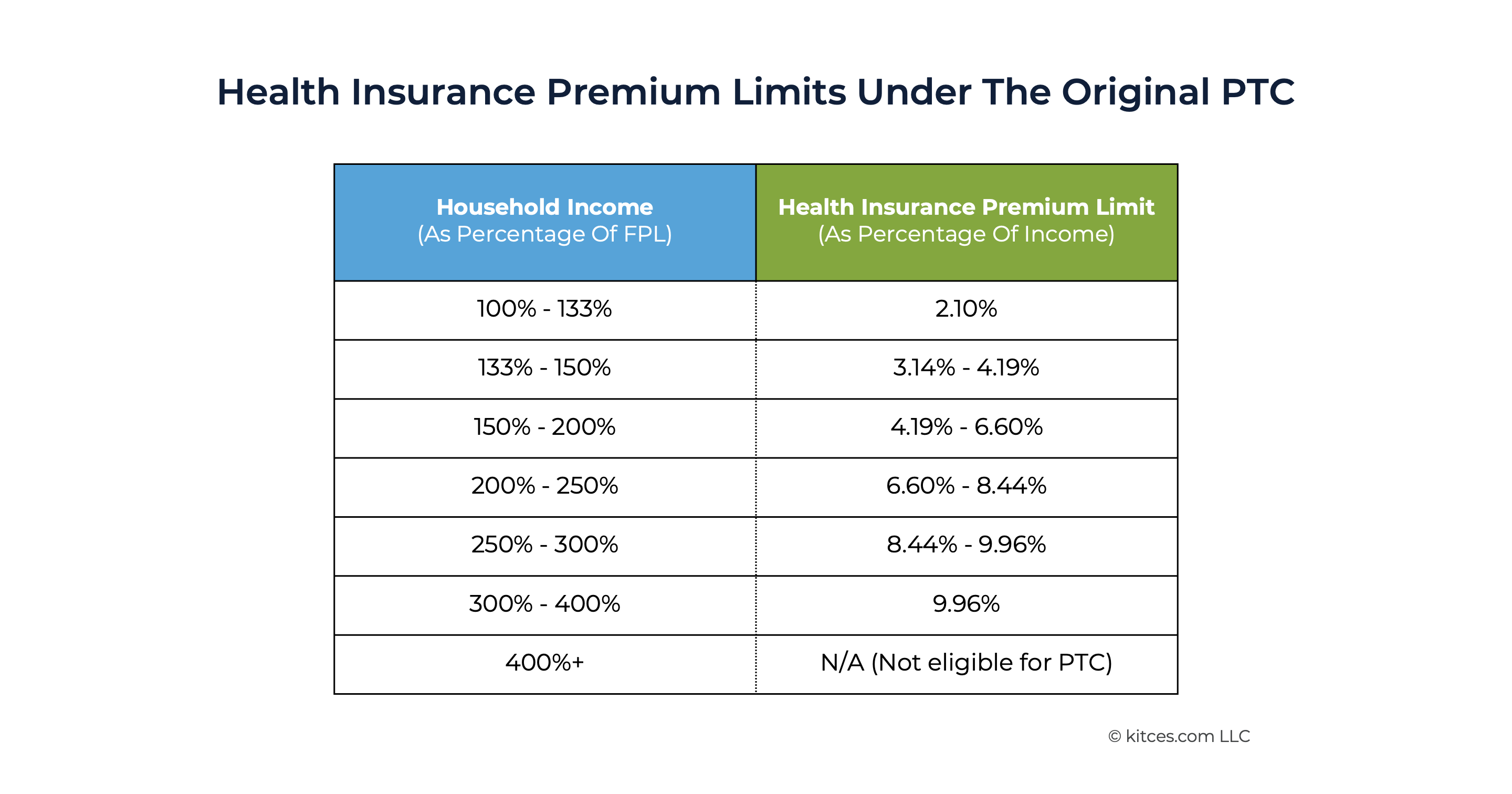

Prior to 2021, the PTC was only available for households with income between 100% and 400%. Those with income lower than 100% of FPL were expected to qualify for and enroll in Medicaid, which is subsidized or free in most cases; those with more than 400% of FPL were simply expected to cover the full cost of their own insurance. This resulted in a steep cutoff in the PTC – and a corresponding increase in Marketplace insurance premiums – for those who went over the income cutoff: Earning even one dollar over the 400%-of-FPL threshold eliminated PTC eligibility entirely.

What's more, if someone underestimated their income while enrolling in Marketplace coverage and received PTC-subsidized premiums during the year, those subsidies needed to be paid back in full when filing the tax return at the end of the year. In other words, 'accidentally' earning a little too much during the year could result in a surprise multi-thousand-dollar bill come tax season.

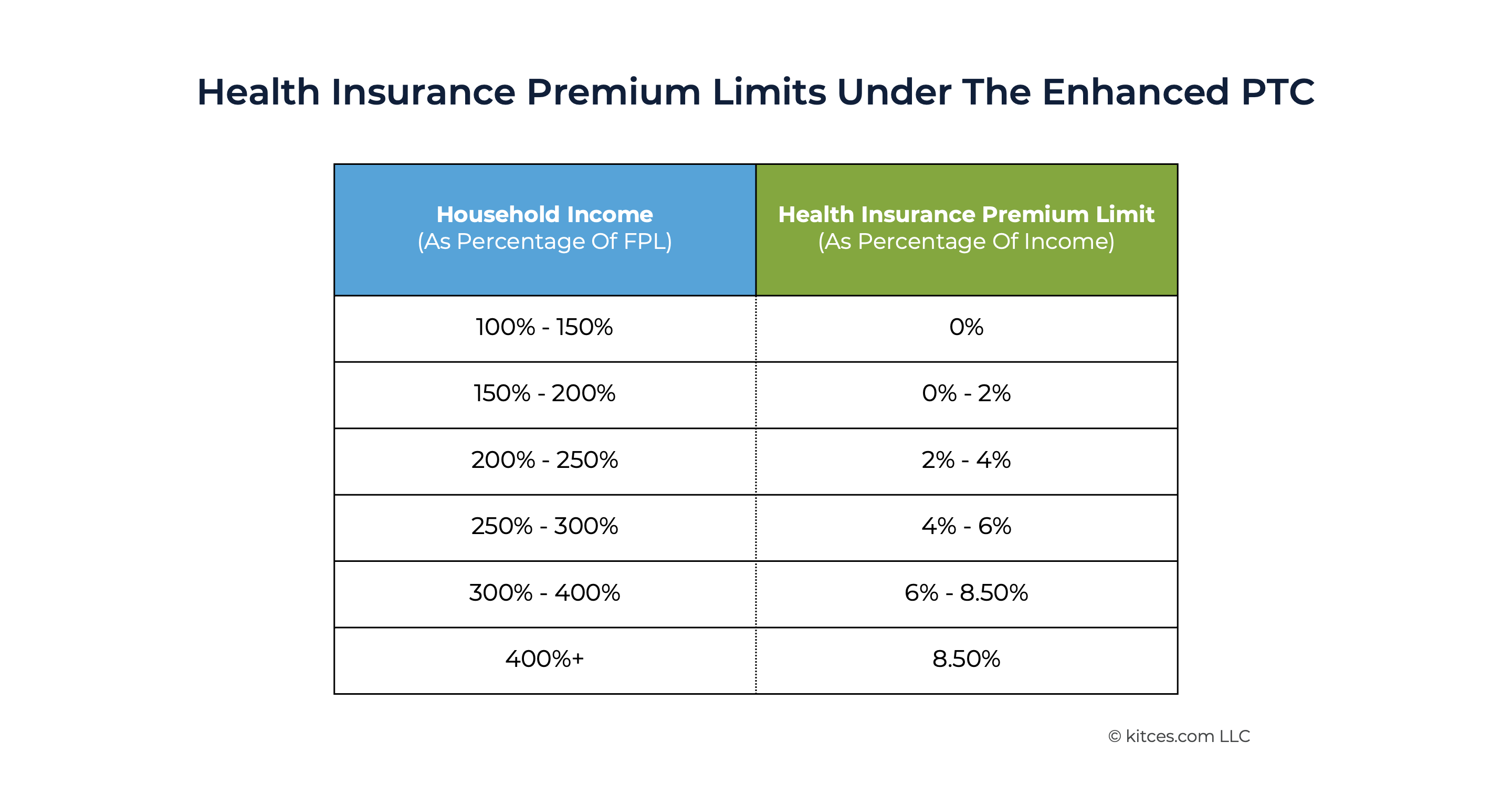

In 2021, in the midst of the COVID pandemic, Congress enacted changes that created the 'enhanced' Premium Tax Credit. These changes eliminated the 400%-of-FPL cutoff for PTC eligibility and reduced the percentages of income that individuals were required to contribute to their monthly premiums. As a result, those who were already eligible for the PTC paid less for their health insurance premiums (or at least were subject to lower premium increases as the amounts charged by insurers increased over time). And many who hadn't been eligible for the PTC due to having income over 400% of FPL were now able to take advantage of the subsidy.

Under the enhanced PTC rules, households with income of 150% of FPL or less were required to pay 0% of their income for health insurance, effectively making their premiums 100% subsidized. As shown below, the premium limitation rises along with income as a percentage of FPL, up to a maximum of 8.5% for those with income of 400% or more of FPL.

However, the enhanced PTC was only intended as temporary relief during COVID and the subsequent spike in inflation during the early 2020s. As such, it is scheduled to expire at the end of 2025, at which point the PTC calculation will revert to the pre-2021 rules. In 2026, then, the premium limitation for those with income of 100% of FPL starts at 2.1% of income and jumps up to 3.14% at 133% of FPL. From there, the percentage rises to 9.96% at 300% of FPL and stays there until household income reaches 400% of FPL – above which the taxpayer is no longer eligible for any amount of PTC.

In other words, the expiration of the enhanced PTC will effectively have the opposite of its original impact on health insurance premiums. Nearly everyone on an exchange plan will pay higher out-of-pocket costs for their insurance as the out-of-pocket premium limits are reverted higher, and households with income higher than 400% of FPL – even just $1 over the line – will be cut off from the subsidy altogether.

How the expiration of the enhanced PTC will affect clients in dollar terms will vary widely, since the credit amount is driven mainly by the income and number of people in each household. The case studies that follow look at three different scenarios to illustrate this point.

Single-Person Household

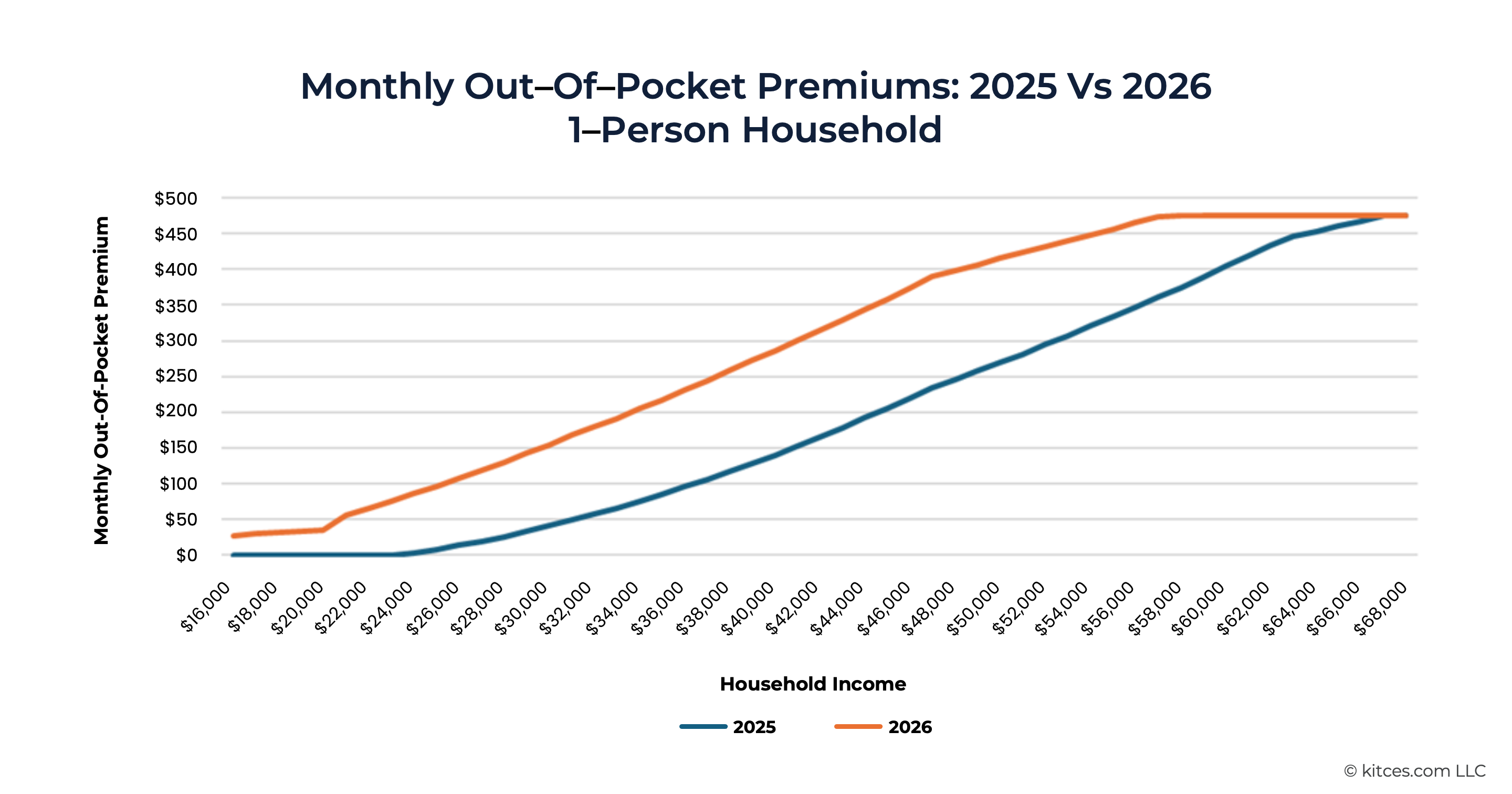

First, imagine Kelsey, who is a 30-year-old single person with a Marketplace health insurance plan that costs $475 per month before the Premium Tax Credit. We'll assume for purposes of the example that Kelsey has the same amount of income in both 2025 and 2026.

As shown below, the difference between Kelsey's 2025 and 2026 PTC – and therefore the difference between her out-of-pocket insurance premium (ignoring any increase in the cost of the insurance itself for simplicity) – is highest if she earns around $48,000 per year. At that income level, her out-of-pocket premium costs would increase by about $155 per month ($1,860 per year) in 2026.

The difference shrinks as Kelsey's income grows, however, and disappears entirely if she earns more than $68,000. At that level of income and beyond, her premium limit in 2025 under the enhanced PTC – i.e., the maximum percentage of her income that she's required to pay out-of-pocket – is higher than the cost of the premium itself.

In other words, because she would be required to pay the full cost of the insurance premium under both the enhanced and non-enhanced versions of the credit, the enhanced PTC's expiration won't result in any out-of-pocket premium increase.

The key point is that while a single person may see a modest increase in their monthly insurance premiums if they earn less than $68,000, they won't see much difference if they earn more than that (other than the insurance itself getting more expensive, which unfortunately is harder to avoid no matter the income level).

Family Of Four

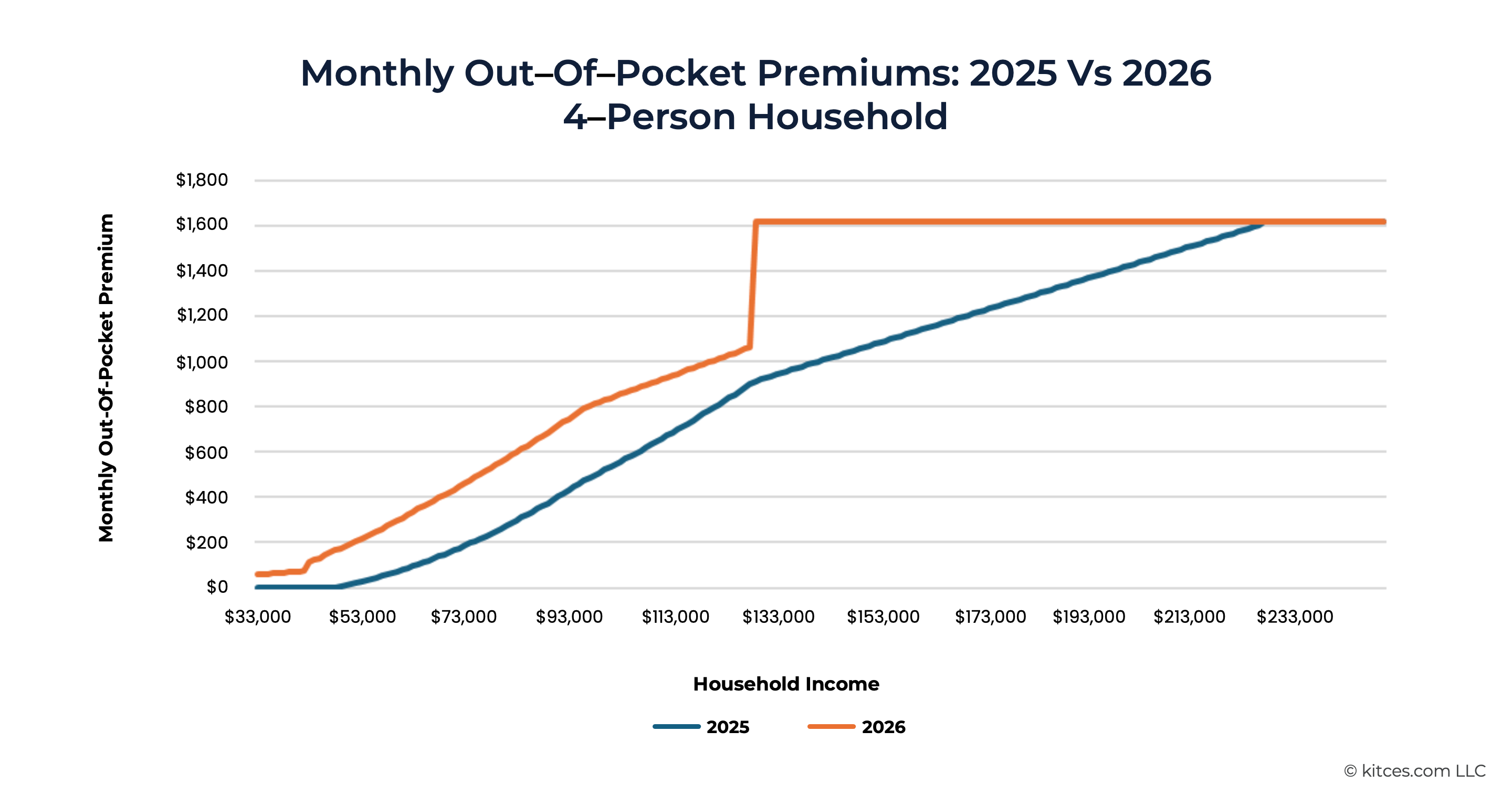

For the next example, imagine a 45-year-old couple, Martha and Travis, with two children aged 12 and 7, who are all covered by a Marketplace plan. In this case, the family's insurance costs $1,620 per month.

As shown below, the impact of the enhanced PTC's expiration varies greatly depending on the family's income level. If Martha and Travis are at or below $128,600 of income (400% of FPL for a family of four), they will likely see a $200 to $300 increase in their out-of-pocket monthly insurance premiums. Which is bad enough on its own, but the moment they go above 400% of FPL (at which point they become ineligible for any PTC in 2026), the monthly premium increase spikes to over $700 (more than $8,400 over the entire year).

The difference shrinks as income increases from there, since the family would be eligible for less and less of the enhanced PTC to begin with, and if they earn more than $228,000, they would be paying the full cost of the insurance under both the enhanced and non-enhanced PTC.

The impact of the enhanced PTC's expiration, then, is greater on bigger households with more expensive insurance to cover everyone in the family. For Martha and Travis, going from $128,600 to $128,601 of household income causes them to go from an expected premium increase of $160 per month to around $700 per month. Or put differently, that dollar of extra income would cost 12 × ($700 − $160) = $6,480 in additional insurance premiums.

Couple With No Dependent Children

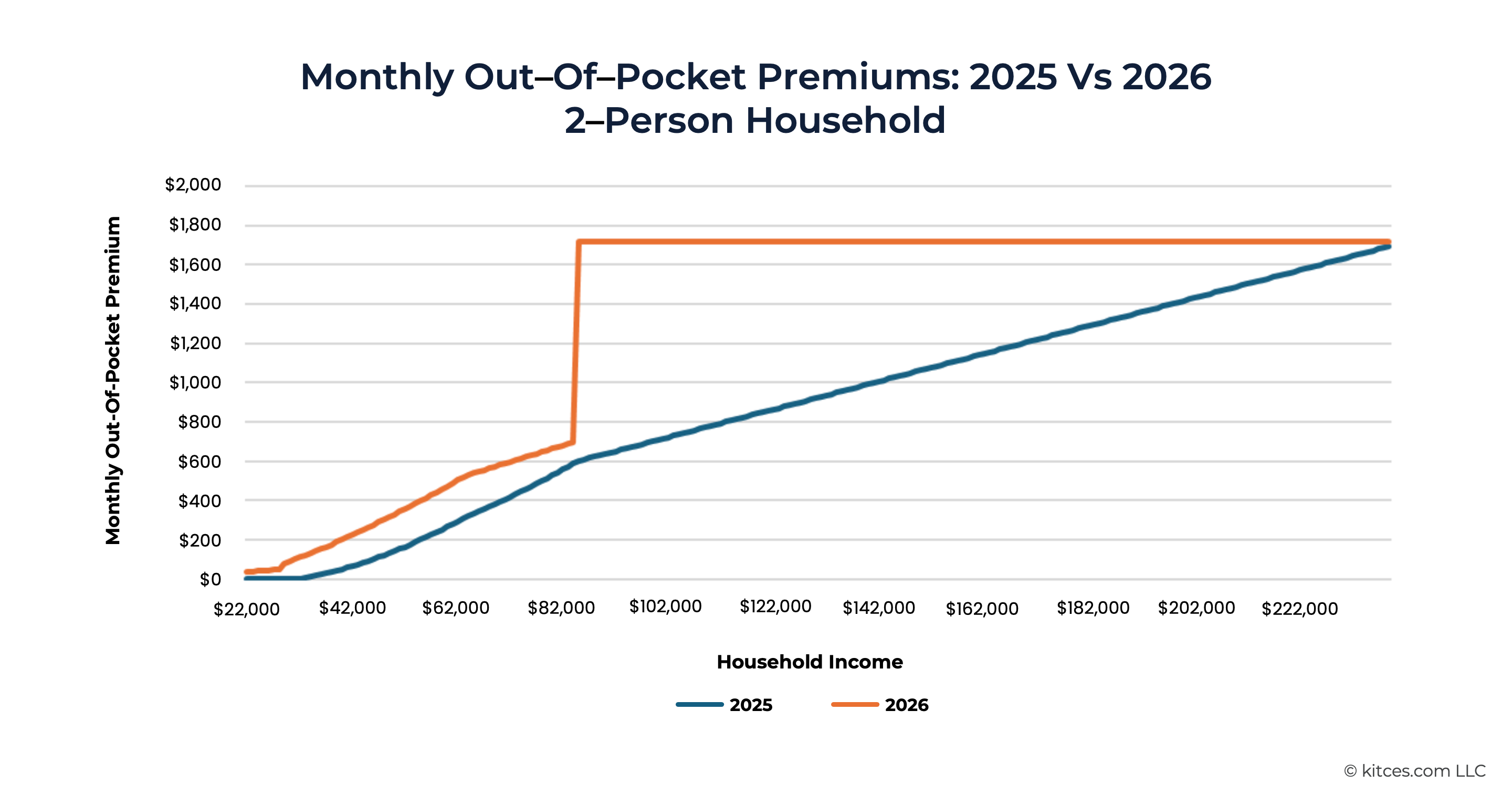

Finally, imagine a 60-year-old married couple, Maxine and David, with no dependent children. They've decided to retire and are covering the gap between employment and Medicare eligibility at age 65 with a Marketplace insurance plan that costs $1,720 per month. Since they're retired and not yet eligible for Social Security benefits, they'll be covering their living expenses entirely through a combination of interest, withdrawals from their taxable investment accounts, and distributions from their pre-tax and Roth IRAs.

In this case, the cliff at 400% of FPL is even more pronounced. Once Maxine and David's income exceeds $84,600 (400% of FPL for a two-person household), the expected premium increase jumps from just over $100 per month to over $1,100 per month. And the difference between the 2025 and 2026 premiums doesn't disappear unless the couple has over $242,000 in income.

Again, just a dollar of income over the 400%-of-FPL threshold increases their monthly premium to over $1,100. Meaning that single dollar could cost the couple over 12× ($1,100 − $100) = $12,000 in out-of-pocket insurance premiums over the course of the year. That's a 1.2 million percent marginal tax rate on that dollar of income alone. And from a bigger-picture perspective, the fact that this couple is now on the hook for their entire $1,720 monthly insurance premium ($20,640 per year) means that their insurance costs alone would eat up $20,640 ÷ $84,601 = 24% of their pre-tax income.

While higher-income households might be able to weather such cost increases more easily, those with income just over 400% of FPL could experience a significant cash flow crunch based on the higher cost of their premiums.

Other client situations might see different effects, and online calculators such as this one from Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) can help estimate the impact of the scheduled PTC changes on individual clients. But the key point is this: The biggest impact of the enhanced PTC's expiration by far will fall on households with income just above the 400% of FPL cutoff, and especially those with multiple family members and/or more expensive insurance coverage. Higher-income households will see little change if they weren't eligible for the PTC under the 'enhanced' rules from 2021–2025, but for those who have been benefiting from the PTC over the last few years, they'll likely see a substantial increase in 2026 – which could be particularly stark if their income falls over 400% of FPL.

Planning Strategies To Preserve The Premium Tax Credit (For Households That Need It Most)

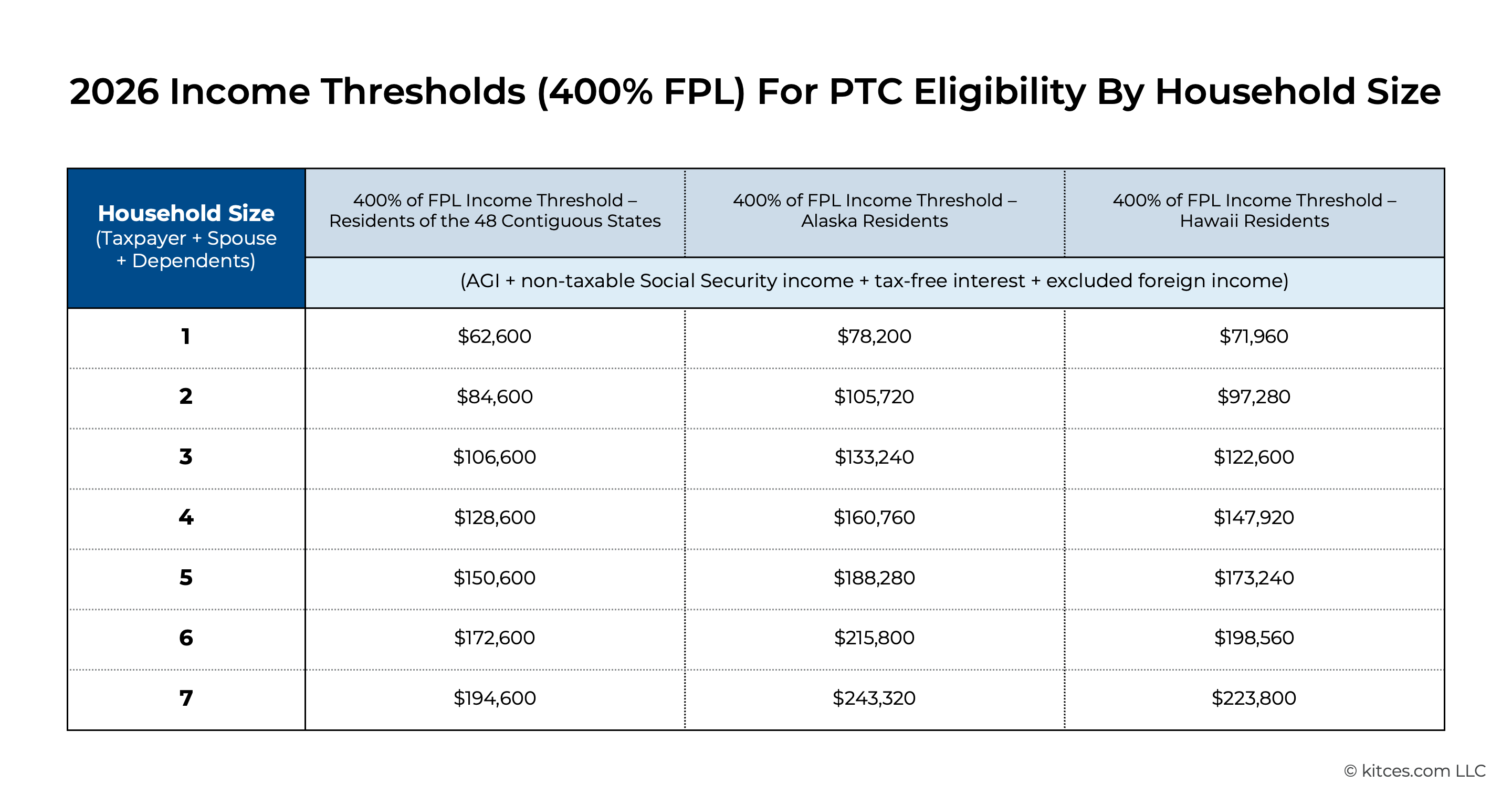

The greatest impact of the expiration of the enhanced PTC credit will fall on households whose income is just over the 400%-of-FPL threshold, which will cause them to become ineligible for any PTC. Those income thresholds for 2026 are as follows:

It follows that the households standing to benefit the most from planning around the PTC changes are those that can reduce their income below the 400%-of-FPL thresholds in order to preserve their PTC eligibility.

As noted earlier, many types of people may be enrolled in Marketplace health insurance plans (and therefore are eligible for the PTC). Broadly, they tend to fall into two categories:

- Those who are still working (e.g., self-employed individuals or employees without access to affordable employer coverage); and

- Those who are retired or between jobs.

Because of the different circumstances of each group, the planning strategies to preserve PTC eligibility will vary accordingly.

Preserving PTC Eligibility For Working Clients

For clients who are still working, the biggest challenge is that they already have a certain level of income, and most people don't want to take a salary cut just for the sake of lowering their health insurance premiums. Thus, the planning strategies for keeping them below 400% of FPL focus on reducing their AGI after accounting for wages or self-employment income. This typically means homing in on above-the-line deductions or income exclusions that the individual may be eligible to claim.

Nerd Note:

The new deductions created under the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA), including qualified tips of up to $25,000, qualified overtime wages of up to $25,000, qualified auto loan interest of up to $10,000, and qualified charitable contributions for taxpayers taking the standard deduction of up to $2,000, are all below-the-line deductions that do not reduce AGI. Thus, none of these deductions will impact an individual's eligibility for the Premium Tax Credit.

Pre-Tax Retirement Contributions

For many people, one of the first places to turn for reducing their AGI will be deductible (i.e., pre-tax) retirement contributions. Those with access to a 401(k) plan can make up to $24,500 in employee contributions in 2026, and most participants age 50 and up can make an extra $8,000 catch-up contribution – except those who are age 60 through 63, who can make an $11,250 catch-up contribution under a rule created by the SECURE 2.0 Act.

Additionally, self-employed individuals with a solo 401(k) plan can contribute up to 20% of their net self-employment income as a pre-tax employer contribution, up to a combined (employee plus employer) contribution of $72,000, plus any catch-up contributions the participant is allowed to make.

Example 1: Sherri is a 50-year-old self-employed business owner. She supports her spouse and two dependent children, and buys health insurance from her state's insurance exchange. She expects that she'll earn $200,000 in net self-employment income in 2026.

Sherri's $200,000 net self-employment income alone would put her well over the $128,600 (400% of FPL) threshold for a family of four. However, with her business's solo 401(k) plan, she can make up to $24,500 in employee contributions, $8,000 in catch-up contributions, and $200,000 × 20% = $40,000 in employer contributions.

By maximizing all of her possible deductible solo 401(k) contributions, Sherri can reduce her income to $200,000 − $24,500 − $8,000 − $40,000 = $127,500, which puts her just below the $128,600 cutoff and allows her to be eligible for the PTC. Her income would be further reduced by the self-employed health insurance and one-half of self-employment tax deductions.

If both spouses are working and have access to retirement plans, they can each make contributions to their respective plans to reduce their household income. In situations where only one spouse earns income, the other spouse may be able to make an IRA contribution of up to $7,500 (plus an extra $1,100 catch-up contribution if they're age 50 or older).

It's also worth noting that the rules for solo 401(k) plans allow both the business owner and their spouse to participate in the plan (if the spouse earns income from the business). In situations where one spouse is self-employed, they could opt to hire their spouse and pay them wages to work in the business – which would allow both spouses to contribute up to the maximum solo 401(k) limits.

Example 2: Georgette and Leonard are a married couple who are both age 60 with no dependent children. Georgette is self-employed and estimates her net self-employment income will be $150,000 in 2026, and Leonard no longer works.

For a two-person household, the 400%-of-FPL threshold where the PTC is eliminated is $84,600. If Georgette hires Leonard to do administrative work for her business and pays him a $40,000 salary, they can both now participate in Georgette's solo 401(k) plan.

If they each make the maximum employee contribution of $24,500 and the age 60 catch-up contribution of $11,250, they can reduce their household income to $150,000 − 2 × ($24,500 + $11,250) = $78,500, putting them under the $84,600 threshold and making them eligible for the PTC.

While the above examples involve substantial contribution amounts – and not everyone will want to allocate this much of their income toward retirement savings where it can't be spent right away – they illustrate how powerful retirement contributions alone, particularly solo 401(k) plans, can be for lowering income to preserve PTC eligibility.

With a solo 401(k) plan, the business owner can wait until the very end of the year (when they're likely to know their household income for the year with a high degree of certainty) to decide on their employee contribution amount, and until the tax filing deadline to decide on their employer contribution. Which means that if they're in danger of crossing the 400%-of-FPL threshold and losing their PTC (which would require them to pay it all back upon filing their tax return), there's flexibility to act after year-end to contribute enough to put them safely back under the threshold.

HSA And FSA Contributions

In addition to retirement contributions, individuals can also make contributions to Health Savings Accounts (HSAs) and Flexible Spending Accounts (FSAs). These are above-the-line deductions and therefore reduce the household income counted toward calculating the PTC.

In 2026, people with self-only insurance coverage (i.e., that covers themselves and no one else) can contribute up to $4,400 to an HSA, while those with family coverage (that covers themselves plus any other household members) can contribute up to $8,750.

While the ability to make HSA contributions has traditionally been limited only to people covered by High-Deductible Health Plans (HDHP) with specific deductible and out-of-pocket maximum restrictions, a new rule introduced by the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA) allows HSA contributions for individuals covered by any Bronze-level Marketplace plan or Catastrophic plan (generally only available to people under age 30 or who meet specific affordability exemptions), starting in 2026. So while many individuals using Marketplace plans have already enrolled in a plan for 2026, they may still be able to contribute to an HSA even if they're enrolled in a plan that doesn't meet the old definition of an HDHP.

Contributions to FSAs are also above-the-line deductions, although unlike HSA contributions they can't be made by self-employed individuals – they're only available for employees of a separate business entity. Healthcare FSAs, which can be used for qualified healthcare costs, have a contribution limit of $3,400 in 2026, while dependent care FSAs – which can be used for day care, camps, and other childcare costs for dependents under age 13 – have a limit of $7,500. The caveat is that these funds must generally be used by the end of the calendar year – otherwise they're forfeited by the employee and lost for good.

Timing And Treatment Of Business Income And Expenses

Since many of the people using Marketplace insurance are self-employed, they may have some flexibility on the timing and treatment of certain business income and expenses that can allow them to stay below the 400%-of-FPL threshold.

Most small businesses are taxed on a cash basis, meaning that income and expenses are recognized on the date they're actually received or paid out. This can give business owners some leeway in deciding when to 'earn' income. For example, imagine that it's December 2026 and a self-employed consultant is wrapping up a project for a client. The consultant looks at their income for the year and realizes it's just under the 400%-of-FPL line, and that the extra income from the client would cost them their eligibility for the PTC that year. In that case, the business owner could decide to wait until January 2027 to bill the client for the work, ensuring that the income doesn't count toward their 2026 PTC calculation.

Conversely, rather than delaying income into the next year, a business owner could decide to accelerate certain expenses into the current year, which would have the same net effect on lowering business income (and therefore household income for PTC purposes). A business owner could elect to pay the rent on their office space a little early, doing so in December rather than January. Or they could invest in new equipment: The One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA) permanently allows 100% bonus depreciation for most property with a depreciable life of 20 years or less, which includes almost all business equipment other than real estate property. Almost any depreciable property that a business can buy, then – computers, printers, software, office furniture, factory equipment, etc. – would likely be 100% deductible.

Preserving PTC For Non-Working Individuals

Even though they may not be earning wages or business income, individuals who are no longer working usually still incur some taxable income: From taxable retirement account withdrawals to annuities to Social Security benefits to interest, dividends, and capital gains in taxable accounts. The planning goal in these cases is for the client to have enough income to meet their cash flow needs, while ensuring that their taxable income (or more precisely, their MAGI) doesn't cause them to lose their PTC and drive their health insurance premium costs skyward.

Setting A MAGI Budget For The Year

Unlike self-employed people, non-working individuals don't have the same flexibility to adjust income and expenses and elect retirement contributions at the end of the year if it's looking like their income will exceed 400% of FPL. There's very little they can do to lower their MAGI once it's already crossed the line, especially when they're no longer making retirement contributions. They may be able to make an HSA contribution if they're enrolled in a qualifying plan, but if doing so requires making a distribution from a different account (such as an IRA) that will generate more taxable income, then the contribution would, at best, just cancel itself out.

It's very important, then, for non-working people enrolled in Marketplace plans who want to stay eligible for the PTC to set a 'MAGI budget' for the year, allowing them to incur only the amount of income that would keep them eligible for the PTC.

For example, a married couple with no dependent children living in a mainland US state would have a MAGI budget of $84,600 (i.e., their 400%-of-FPL threshold) for PTC eligibility. MAGI for PTC purposes includes AGI plus any non-taxable Social Security benefits (i.e., the amount in excess of the 0%, 50%, or 85% of benefits that are normally taxable based on household income) plus tax-free interest. So for households receiving Social Security benefits or investing in municipal bonds, there will be more income contributing to the MAGI budget than what's shown on the tax return.

Once a MAGI budget is established, it's possible to plan on how to structure withdrawals and other income so they can keep their MAGI within budget while still covering their living expenses for the year. For example, if the couple above needs $100,000 per year to meet their living expenses, they can't just take $100,000 from their pre-tax IRA: The entire amount would be considered taxable income and would cause them to go over their $84,600 MAGI budget. However, if they have Roth accounts available, they can take a mix of (taxable) pre-tax and (tax-free) Roth distributions to stay within budget. Or if they have taxable investment accounts, they can tap those as well, making sure that any capital gains they incur don't put them over budget (as investment income counts toward household income for PTC purposes, too).

In many cases, these strategies may run counter to traditional tax planning strategies for non-working people. Low-income years are often considered a prime opportunity to recognize income at relatively low marginal tax rates by converting pre-tax assets to Roth or by harvesting capital gains at 0% capital gains rates. These options could still be possible for clients on Marketplace insurance plans, but the MAGI budget generally becomes the guiding constraint rather than the individual's Federal income tax bracket.

For example, in 2026, the standard deduction for a married couple will be $32,200 and the 0% capital gains tax bracket goes up to $98,900 of taxable income. In theory, then, a married couple could convert $32,200 of pre-tax assets to Roth (which is entirely offset by the standard deduction) and recognize an additional $98,900 of long-term capital gains (which are taxed at 0%), resulting in $0 of Federal income tax owed.

Except that if a couple were to do this, they would have $32,200 + $98,900 = $131,100 of household income counting toward their PTC calculation – above the $84,600 threshold (i.e., 400% of FPL for a two-person household) – making them ineligible for the PTC and on the hook for their entire health insurance premium. Which, as described in the earlier case studies, could require them to pay an extra $1,000 or more per month in insurance premiums even if they owe no additional Federal tax. If they were instead able to keep their combined Roth conversions and realized capital gains below $84,600, then they would still owe $0 in Federal tax, but would also preserve their eligibility for the PTC and avoid the unpleasant surprise of having to repay it when they file their 2026 tax returns.

Nerd Note:

Under the enhanced PTC rules from 2021–2025, individuals with income under 400% of FPL are limited in the amount of PTC they are required to repay if they overestimated the credit during the year.

For example, if a single filer estimated that their income would qualify them for a PTC of $6,000 when enrolling in a Marketplace plan at the beginning of 2025, but their actual income only qualified for a PTC of $3,000, they would only need to pay back a maximum of $1,625 when filing their 2025 tax return rather than needing to make up the full $3,000 difference.

However, beginning in 2026, with the expiration of the enhanced PTC, all taxpayers will be required to repay the full amount of any excess PTC paid during the year. Households that receive subsidized insurance premiums but ultimately exceed 400% of FPL will be disqualified from the PTC and required to repay the entire subsidy at tax time.

Adjusting PTC Amounts After Enrolling In A Plan

At this point, most people with Marketplace health insurance have enrolled in a plan for 2026, since the enrollment deadline for a plan starting January 1 was on December 15. That means they've already estimated their 2026 income and learned how much PTC they are eligible for based on that income, since that's a part of the enrollment process. And if their estimated income for 2026 is higher than 400% of FPL, then they've already seen how much their out-of-pocket premiums are set to increase after the new year.

But even for someone who's already enrolled in a health insurance plan for 2026, it's not too late to put planning strategies in place to help them lower their out-of-pocket premium. The insurance exchanges allow enrollees to update their existing insurance application midyear to account for significant life changes that can affect their coverage. This includes changes in income: If there's an expected drop in income during the year, including after implementing planning strategies like retirement plan and HSA contributions or adjusting distributions from retirement accounts, then an enrollee can report that change and receive an updated estimate for their Premium Tax Credit and out-of-pocket insurance premium cost for the remainder of the year.

For advisors, it's not too late to reach out to clients who are enrolled in Marketplace health insurance, and particularly those whose income falls just beyond the 400%-of-FPL threshold under the non-enhanced PTC rules, to check in on their expected health insurance costs for 2026. If the client has been notified of a significant premium hike, then it's time to discuss whether there are any opportunities to reduce countable income enough to qualify for the PTC: either through retirement or HSA contributions, shifting business income and expenses, or adjusting withdrawals from accounts to fund living expenses without exceeding 400% of FPL. If household income can be brought back under the cutoff, the client can update their application to reflect their new expected income and see the revised PTC reflected in future insurance premiums.

Lastly, it's important to note that if there is an agreed-upon strategy to reduce income enough to qualify for the PTC, the advisor can help to ensure that the client actually follows through on that strategy. Advisors may find it helpful to check in several times throughout the year to monitor whether the client's income remains on track to stay below the 400%-of-FPL level or if more adjustments need to be made. And if the client's income unexpectedly turns out to be higher than predicted – to the extent that there's nothing they can do to stay below the 400%-of-FPL threshold – then it's important for the enrollee to update their application to reflect that change as well, or, at the very least, be prepared for the possibility of a very high tax bill at the end of the year if they're required to repay their advanced PTC (the pain of which will hopefully be softened by the 'surprise' of a very good income year!).

Leave a Reply