Executive Summary

"Planners and academics need to work together to develop a profession with evidence-based practices." That is the message given at the FPA Retreat by Dr. Michael Finke, a professor of personal financial planning at Texas Tech University, and a co-author of mine at the Journal of Financial Planning.

Yet while the Journal of Financial Planning is a great resource, and it has been the go-to outlet for research on retirement planning from the perspective of practicing financial planners, especially regarding safe withdrawal rate strategies, the academic research approaches the retirement challenge from a different perspective and focuses on different tools and strategies.

Ultimately, researchers can use their technical skills to investigate optimal retirement strategies, and practitioners can guide these investigations by suggesting real world constraints and ideas for solutions, and even by sharing in the nitty-gritty process of conducting the research. Let’s encourage these interactions to get rigorous analyses which can be applied to real-world problems.

Though I am generalizing somewhat, the planner’s view on retirement income most commonly focuses on safe and sustainable spending rates to draw down one’s financial wealth during retirement. Since the publication of William Bengen’s 1994 article using historical data to provide guidance about sustainable withdrawal rates, discussions have centered on the 4% rule of thumb for sustainable spending. Though vigilance is expected, with a broadly diversified portfolio of stocks and bonds (Bengen suggested 50-75% stocks), retirees should be able to rely on spending an inflation-adjusted amount over 30 years equal to 4% or 4.5% of their retirement date assets. Extending the research to Monte Carlo simulations, probabilistic thinking is encouraged and the focus turns to keeping failure rates sufficiently low.

But the notion of a safe withdrawal rate from a portfolio of volatile assets is somewhat perplexing for academics trained in the theory of life-cycle finance. Their idea is that failure, at least for meeting basic needs, should be eliminated. Life-cycle finance, which Paula Hogan summarized well for JFP readers in 2007, views hedging (such as with a bond ladder) and insuring (such as with fixed income annuities) as important risk management tools beyond precautionary savings (saving enough to use a ‘safe’ withdrawal rate) and portfolio diversification. Life-cycle finance also informs us that current market conditions are much more relevant than historical averages.

Actually, the 4% rule does stand on a rather flimsy basis. It worked during an exceptional and perhaps anomalous period in world history when the United States rose to become the world’s leading superpower. Testing the 4% rule with data for other developed market countries leads to some rather shocking results. Alternatively, especially around the year 2000, market valuations rose to unprecedented levels and we do not have a basis in U.S. history for knowing about sustainable spending from such a starting point. Today the issue centers more on low bond yields, suggesting that we should plan for more modest stock and bond returns than the U.S. averages since 1926.

Markets tend to surprise us frequently, and retirees only get one whack at the cat. With Modern Retirement Theory, Jason Branning, CFP®, and Dr. M. Ray Grubbs inform us that basic expenses should be covered by income sources that are “secure, stable, and sustainable.” For basic needs, retirement income strategies must work by construction. According to the Retirement Income Industry Association (where I serve as curriculum director for the Retirement Management Analyst designation), the fundamental goal of retirement planning is to “first build a floor, then expose to upside.” This is life-cycle finance theory as used in practice.

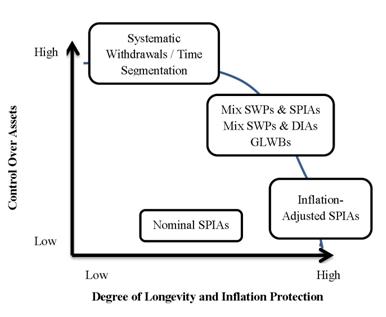

That being said, I do not suggest abandoning research on safe withdrawal rates. I think we can instead build a more complete framework. Consider the chart to the right. Academics are puzzled about why individuals are not more willing to annuitize their assets. That would eliminate longevity risk. But it is clear that many people are loath to give up control over their assets. That is why inflation-adjusted single-premium immediate annuities (SPIAs) are at the bottom right of the chart. Nominal SPIAs are to their left, since their real spending power may decline dramatically.

That being said, I do not suggest abandoning research on safe withdrawal rates. I think we can instead build a more complete framework. Consider the chart to the right. Academics are puzzled about why individuals are not more willing to annuitize their assets. That would eliminate longevity risk. But it is clear that many people are loath to give up control over their assets. That is why inflation-adjusted single-premium immediate annuities (SPIAs) are at the bottom right of the chart. Nominal SPIAs are to their left, since their real spending power may decline dramatically.

On the other hand, systematic withdrawals, from a portfolio focused either on total returns or on a time-segmented bucket approach, are a time-honored and understandable topic for planners and their clients. I rate them as low in terms of protection, but high in terms of control over assets. I should note however, that Bob Seawright rightfully pointed out that this control over assets may be an illusion. Poor market returns, high inflation, and a long life may severely constrain one’s control.

Where research about retirement income strategies is ultimately heading is to the box which includes strategies with partial annuitization, the use of deferred income annuities (DIAs), and variable annuities with guaranteed lifetime withdrawal benefit riders (GLWBs). Moshe Milevsky, Mark Warshawsky, Joseph Tomlinson, and Peng Chen are a few names who are already making an impact in this area. Ultimately, though, the best solutions must incorporate both academic rigor, and the practitioner and client challenges of the real world.

Here are a few ideas about how to better integrate the approaches used by financial planners and academics with regard to retirement income strategies:

- It is time to abandon the idea that retirees should focus on finding a spending strategy that maintains a rather low failure rate, as is par for the course with safe withdrawal rate studies. This narrow focus ignores the lost potential enjoyment from spending more, it ignores how much flexibility retirees may have to cut their spending at a later date, it ignores the availability of other spending resources outside of the financial portfolio (such as Social Security) that will continue even in the event of portfolio depletion, it ignores the low probability of still being alive many years after retiring, it ignores any goals to leave a bequest, and it ignores potentially how long the "failure" condition may last. Historical failure rates also don’t help us if current market conditions are different from the historical averages, and they have no meaning when used with variable withdrawal strategies that reduce spending in order to preserve wealth. We need a more complete model that incorporates these considerations.

- Research must increasingly look at variable withdrawal strategies responding to market returns, as well as how to allocate to bond ladders, SPIAs and other retirement products. For strategies with variable spending, we can investigate the degree of lifetime underfunding from a minimum acceptable or desired spending level. Or even better, we can use measures which incorporate the value of spending (as also discussed by Joseph Tomlinson) and recognize that greater spending provides more enjoyment but at a diminishing rate.

- Academic investigations show that a very powerful rule for systematic withdrawals, after building a floor, is to use a withdrawal rate along the lines of 1 / remaining life expectancy (using the life expectancies provided by the IRS for the Required Minimum Withdrawals from IRAs is fine) for each year of retirement. This can be modified to incorporate bequest motives, a greater desire for consumption smoothing, and a return on underlying assets other than zero. We do also need to pay attention to the uncertainty of potentially large health-related expenses later in life.

It is an exciting time to conduct retirement research closely linked to the needs of planners and clients. I do believe we are at a stage in which we can broaden the safe withdrawal rate question and build a more complete framework for developing retirement income strategies which combine insights from both the academic and planning communities. As Michael always asks, I would love to hear your views.

Michael,

Thanks again for this opportunity!

Wade

I welcome new thinking in this area. I have always felt the safe withdrawal rate approach to be inherently flawed given its dependence on historical data for the US market and its focus on a mean variance total return paradigm.

I have often wondered if part of the reason this approach is so common is that many advisors are compensated on an AUM basis. An approach that annuitizes a portion of a client’s portfolio reduces an AUM advisor’s compensation. On its surface, therefore, an AUM model appears to pose a conflict of interest in this realm.

Wade —

One reason some folks might hesitate to plan on variable strategies requiring continuing decisions as they age is concern about, uh, decline in thinking processes as they age. How do you incorporate that consideration in weighing alternatives??

Dick Purcell

Dick,

This is an important point. In this regard, I am trying to focus on simple variable withdrawal strategies. Actually withdrawing a simple percentage should be easiest, as you don’t have to bother looking up the inflation data to see how much you are allowed to spend.

I know you suggest SPIAs as the best way to deal with this problem.

Wade —

I didn’t mean my question as a backdoor way to say “SPIA is better.” I think that here and in posts on your blog you’ve made the case that for many a variable approach will be preferred (“better”). And Michael did too, right here in a post a mere week ago. http://bit.ly/JGpE1w

Seems to me that for folks at the high and low ends, SPIA may not be best: very wealthy don’t need it; and for majority with modest $$, SPIA won’t meet “needs” — they “need” more (hopeful) growth. And some in the “middle” will prefer a variable approach too.

So I am in favor of what you’re doing, just am saying simpler is better as folks age . . .

Dick Purcell

Wade/Michael,

Really enjoyed reading this and would agree that a variable/flexible approach is the best way to handle this question. I know some will be dogmatic about their approach (either on the AUM side or the annuity side), but I have always wondered if the lack of annuitization for retirees has more to do with behavioral issues rather than financial. Very rarely in our lives do we make choices that are truly irrevocable; the choice to annuitize is. Without much (or any) history of making irrevocable decisions, I can understand why people would hesitate to do so; just ask all those investors who were sold charitable lead/unitrusts as a tax avoidance tactic and wanted to get their money out in 2008! “Irrevocable? What do you mean I can’t get my money out??”

The right to change our minds (for better or for worse) certainly appears to be hardwired into our brains, and perhaps that is a contributing factor to the lack of annuitization.

Eric

Eric,

I’ve written a bit about this previously on the blog at https://www.kitces.com/blog/if-immediate-annuities-are-such-a-great-solution-why-doesnt-anyone-want-to-buy-one/

I am VERY skeptical that the compensation issue is a material factor in the “annuity puzzle” (that people don’t annuitize as much as the research implies they should want to). I won’t say compensation has no role, as I’m sure it does, but having been on both sides of the compensation divide I can say that it wasn’t much easier to implement SPIAs when paid for them as when paid via AUM.

I think the driving forces are behavioral, along with a high likelihood that “just annuitize to avoid outliving your assets” is an ineffective oversimplification of how retirees really evaluate the problem. Legacy goals, liquidity desires, and the potential that things could be better down the road are material factors in a client’s decision-making process that I think we are often too quick to dismiss.

– Michael

Interesting discussion. I’ll play the Devil’s advocate. Most advisors are probably familiar with the “mystery shopper” type of study http://www.cepr.org/meets/wkcn/5/5571/papers/N%C3%B6thFinal.pdf where potential clients requested advice and the authors found that the advice was poor.

I would love to see the same thing with SPIAs. Have potential clients with $1.0 million in assets meet 1,000 advisors and state up front their number 1 goal is to not run out of money and that they would like to die broke. See how many advisors recommend SPIAs.

Maybe it is true that clients don’t like SPIAs. Advisors surely do because that is what AUM are. Most advisors see a $1.0 million account as a $10,000/year annuity – and one that should increase over time. How many are willing to reduce it by one-third in the interest of the client?

The reason SPIAs aren’t more prevalent may be because they aren’t often recommended.

Robert –

That study you cite, and reporting about it, are doubly warped:

1. The academics who directed the study and authored the report, from Harvard and MIT along with Hamburg, specifically excluded “better” advisors. But headlines and “news” about it that flew around on the Web, some of it from university professors, did not say that. Just smeared “financial advisors.”

2. The practice that those professors from universities criticized financial advisors for, moving investors from asset classes (index funds) to actively managed funds, was and is taught and enabled by software backed by professors from universities, including Markowitz and Ibbotson.

http://www.dickpurcell.com/debates2/harvardmit-v-markowitz/

The principal source of the problem discovered by professors in our universities is not financial advisors – it’s professors in our universities.

Dick Purcell

Dick,

I’m not arguing whether the study is valid or not although I will admit that my reading of the evidence (not from that study but a lot others)and experience in the industry has led me to conclude that an individual picking an advisor who uses high priced funds to actively manage assets is likely to under perform a low cost indexed approach. I believe at most 20% to 30% of active managers will outperform.

But what I am saying is that I believe (could obviously be wrong and would hope to be) that if I met with 1,000 advisors as a “mystery shopper” and said I have $2 million say and my #1 goal is to not run out of funds, that most would not recommend an SPIA and forego the fees.

Robert,

The point is that in the real world, virtually no one has such a single-minded goal to the exclusion of all others.

Yes, by definition, if you state: “My goal is to never run out of money. I don’t care about my legacy. I don’t care about liquidity. I don’t care about anything except receiving income for life…” then by definition you’ve asked for a SPIA.

That doesn’t mean a SPIA is appropriate for most people’s real world goals, which are more complex and subject to more constraints, stated or otherwise.

I absolutely guarantee you if the single greatest thing that the majority of consumers wanted was a SPIA, they’d be sold. Just slap a 4%, 8%, or 12% commission on the front and there would be a legion of salespeople distributing them to everyone who would be a willing buyer. The fact is that they’re so unsalable, even high-commission SPIAs don’t get sold (which is why there aren’t any of them around these days).

In other words, if the SOLE problem of distribution was compensating agents sufficiently to sell the products, the compensation would adjust. People don’t fail to buy SPIAs because of the compensation. They fail to buy SPIAs despite the compensation because they’re not really that perfect of a match for people’s more complex real-world goals, as well as their real-world biases and preferences (e.g., for liquidity). I’ve been paid to sell SPIAs in the past; you’d be amazed how little difference it made.

– Michael

Michael,

I’m not saying it is the only goal. For many of the people I see it is very important. In fact, the whole subject of SWR wouldn’t be as nearly interesting except that people worry about failure. And I’m not sure failure has been defined. Visiting the kids 2 times /year instead of 3 would be defined by some as failure and by others as being flexible. Would some people give up a bit of legacy and liquidity to lock in 3 visits/year?

The legacy issue is interesting as well because I’ve seen people argue that extra risk can be taken (i.e. increase expected long term performance, read: bigger legacy) because of social security income stream read: annuity. It seems there may be a math problem here. What happens to expected return if we can do 70% stocks/30% bonds with $900,000 invested assets and $100,000 SPIA versus 60/40 say with $1.0 million invested.

By the way I don’t sell annuities but I do tell people to send in the card in the AARP magazine so they at least get a quote and know it is a card in the deck they can play for a portion of their assets if they get overly concerned about markets.

Robert –

This is not aimed specifically at you, but at the widespread practice of talking about the planning target being “expected return.”

That term, from our friends in the universities, is even more blatantly misleading to people than calling return-rate standard deviation “risk.”

So-called “expected return” is NOT EXPECTED! Not a snowball’s chance. If the assumptions are right, the result will probably be below “expected,” maybe way below. The longer the investment term, the further below “expected” the result is expected to be.

I’d prefer talking in terms of real-net-dollar result probabilities, as Michael and his guest Wade do.

Dick Purcell

Interesting how this conversation has moved from the main theme of connecting academia to practicing financial planners to a debate about annuities.

Wade, for what it is worth, the area I am most interested to see analysis done is your second bullet point above particularly the variable spending. In real life, spending is variable. When things are going well, they are a bit looser with their cash. In tough times, they tighten their belts.

I know you are familiar with Jon Guyton’s approach that sure appears to help clients spend more from day 1 of retirement than the original SWR works illustrate. As a practitioner I like that it is workable and clients can understand it. If there are other approaches that produce similar results or improve on those points, I’d love to be able to confer with my clients on the pros and cons of these other approaches.

Keep up the great work,

Dan

Dan,

Thanks a lot for the comment. I haven’t done a comprehensive analysis about different variable withdrawal strategies yet, but I have had an initial look at several types of strategies in my newest research article. It is still a rough draft:

http://ideas.repec.org/p/pra/mprapa/39169.html

One thing that does come out of the analysis is that spending a constant inflation-adjusted amount until wealth is depleted is not an optimal strategy by any sort of evaluation criteria. Withdrawals should adopt to market conditions in some way.

Thanks Wade. I have that on my reading list now.

Dan

Pretty great post. I simply stumbled upon your blog and wanted

to mention that I have really loved surfing around your weblog posts.

In any case I will be subscribing for your feed and I’m hoping you write again very soon!

Thanks for sharing this research for Retirement Income Planning. This is very beneficial for us. Keep sharing..