Executive Summary

Before the SECURE Act was passed in 2019, non-spouse heirs who inherited IRAs could 'stretch' Required Minimum Distributions (RMDs) over their own single life expectancy, often allowing inherited accounts to last for decades. The SECURE Act replaced that treatment with a 10-Year Rule for most non-spouse beneficiaries, who must now fully deplete their inherited accounts within 10 years, typically much sooner than under the stretch rules would have allowed. Yet, in rewriting the law, Congress left one category of beneficiaries unchanged: Non-Designated Beneficiaries (NDBs).

In this guest post, Brad Herdt, a financial planner at Deseret Mutual Benefit Administrators, introduces a strategy that allows financial planning clients to potentially stretch distributions for heirs beyond ten years – by intentionally using NDB treatment.

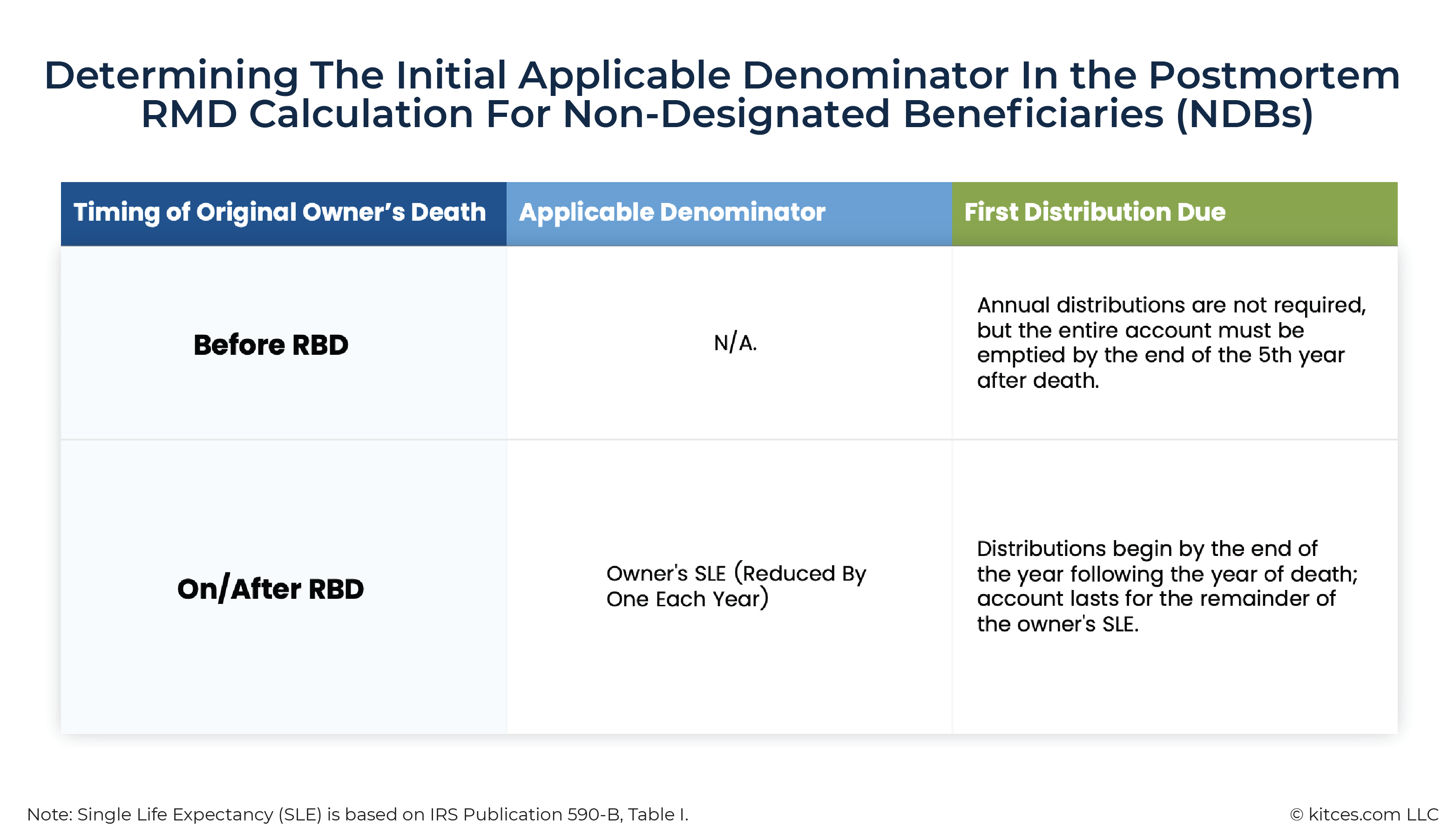

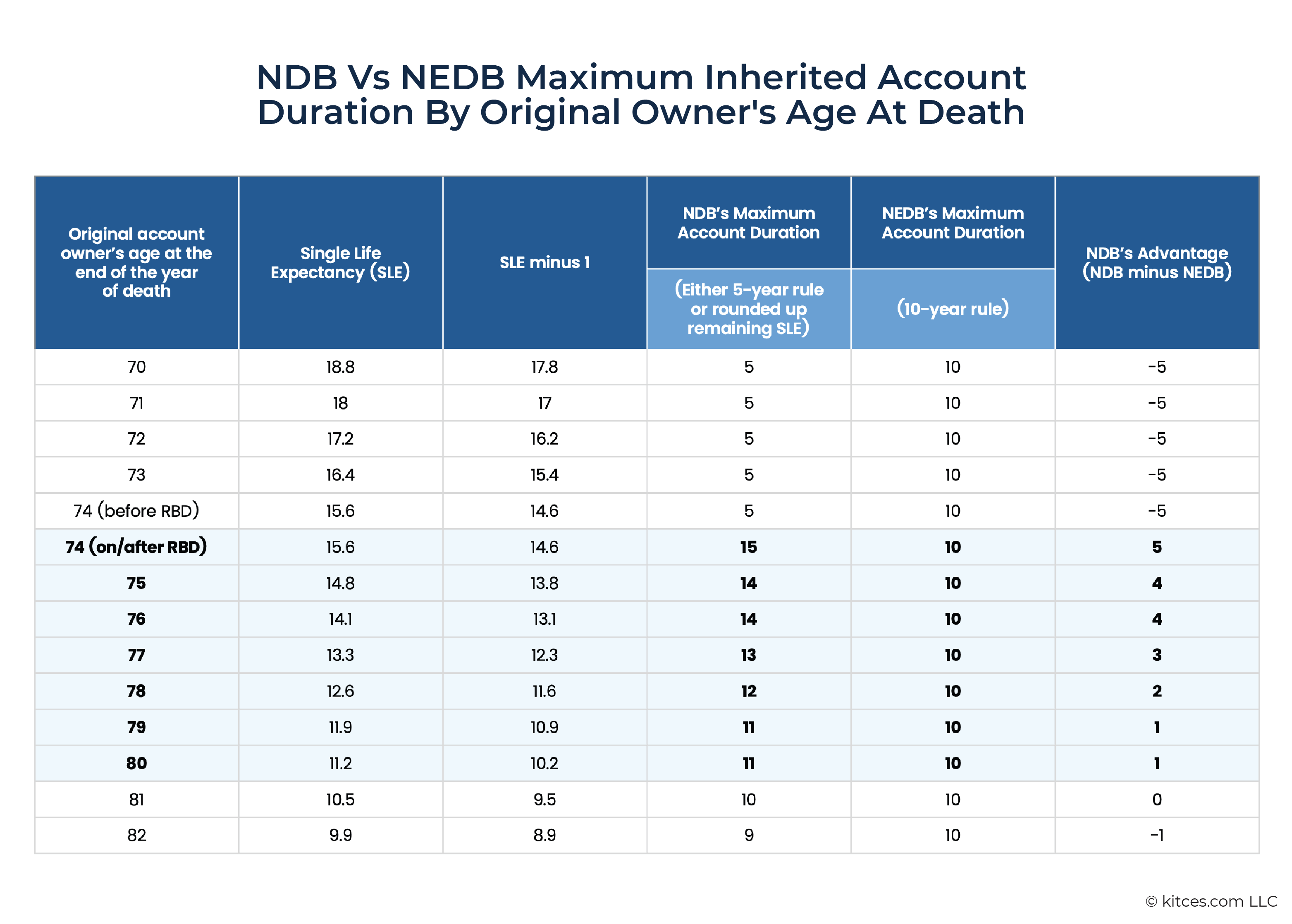

For NDBs, the maximum account lifetime is either five years if the account owner died before their Required Beginning Date (RBD) – the point when RMDs must begin – or the decedent's remaining single life expectancy (reduced by one each year and rounded up) if the account owner died on or after their RBD. Which means that after the owner's RBD, an NDB may potentially be allowed to deplete the account over a longer period based on when the owner dies – unlike Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries (NEDBs), who face a fixed 10-year window to empty the inherited account.

Importantly, once the owner survives past their RBD, the distribution schedules for NDBs is tied to the owner's remaining life expectancy – which, in the early post-RBD years, can exceed the 10-year rule by as much as five years. At that point, deliberately naming specific beneficiary designations, certain types of trusts, or even the owner's estate (all of which can make the heir an 'Intentional' NDB, or INDB) can stretch the payout period well beyond what an NEDB would receive. Still, as the owner ages and their remaining life expectancy shortens, NDB treatment eventually results in a shorter payout period than the 10-Year Rule – making it advantageous to revert back to an individual (i.e., NEDB) designation.

Even under ideal circumstances, though, an INDB's annual RMDs for the first nine years will always be larger than under NEDB rules – front-loading taxable income. Which suggests that a cost-benefit analysis based on each client's unique circumstances (e.g., the intended beneficiaries' tax outlook and distribution behavior, account-specific factors like Roth earnings maturity and sequence-of-returns risk, and the client's own preferences) is essential. Still, for the right clients – such as those with heirs who can absorb higher early traditional account withdrawals, or those with certain Roth employer plans – the benefit of stretching distributions beyond ten years can outweigh the cost.

Ultimately, the key point is that the INDB Strategy can potentially extend the distribution period by up to 50%, giving heirs more time and flexibility in managing cash flow and taxes. And because the strategy's success depends on understanding the IRS timing and rule constraints, financial advisors can play a critical role in both determining when it's appropriate and helping clients implement it effectively!

When the SECURE Act was passed in 2019, it stripped most non-spouse beneficiaries of the so-called stretch provision for IRAs in 2020, and planners have been looking for alternatives ever since. Under the old rules, non-spouse heirs could 'stretch' Required Minimum Distributions (RMDs) over their own single life expectancy, allowing inherited accounts to often last for decades. The SECURE Act replaced that treatment with a 10-Year Rule for most non-spouse beneficiaries, creating a new classification of Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries. These heirs must now fully deplete their inherited accounts within 10 years, typically much shorter than the stretch rules would have allowed.

Industry reports claim there is over $45 trillion invested in IRA and employer-sponsored retirement accounts. Of the IRA assets specifically, more than half were owned by individuals who were at least 65 years old as of the end of 2020 – a share that is expected to rise as over 11,000 individuals reach age 65 each day until 2028.

While much of these retirement assets will be distributed and taxed during the account owners' lifetimes, some will inevitably pass to heirs. For many account owners, giving heirs as much time as possible to draw down the account is a key goal, since a longer distribution period can allow beneficiaries to manage cash flows and taxes more effectively.

As a result, planners have explored several possible replacements for the 'stretch' IRA, such as charitable remainder trusts, life insurance, and Roth conversions. But while these can be valuable tools, they ultimately fall short of the original goal to stretch distributions (since Roth IRAs are still subject to the 10-Year Rule, and CRUTs and life insurance require actuarial assumptions and requirements to be met).

None of these truly restores the long distribution period that the original stretch allowed. Yet, in rewriting the rules, Congress left the treatment of one class of beneficiaries unchanged – the Non-Designated Beneficiary. For financial planners whose clients are looking for a tool that extends distributions for heirs, intentionally using Non-Designated Beneficiary treatment – referred to here as the Intentional Non-Designated Beneficiary (INDB) Strategy – offers a unique, even contrarian, opportunity to achieve stretch-like distributions beyond 10 years.

The Demise Of Stretch IRAs For Non-Spouse Beneficiaries

In 1986, Congress created Required Minimum Distributions (RMDs) for essentially all retirement accounts (including 401(k), 403(b), certain 457(b) plans, and IRAs). The goal was simple: ensure that tax-deferred savings would eventually be realized as income – either during the account owner's life or by their heirs after death.

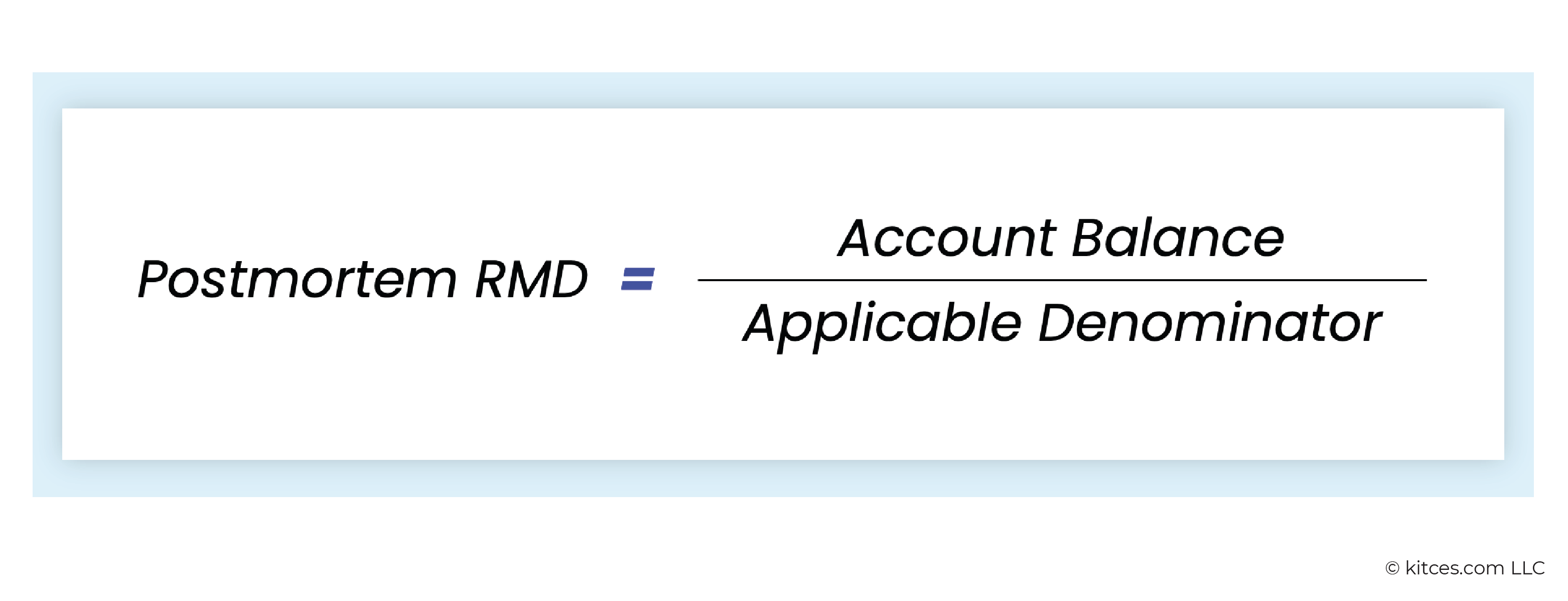

After an account owner dies, the postmortem RMDs are calculated differently than they were for the account owner. For non-spouse beneficiaries, required withdrawals are generally calculated each year according to the following formula:

Postmortem RMDs are determined by dividing the account balance by an 'applicable denominator' value. For all retirement accounts, the account balance is measured as of the prior calendar year. For IRAs, the year-end (12/31) balance must be used, which is also the standard practice for most employer-sponsored retirement plans. This balance is calculated the same way regardless of the type of beneficiary.

The more nuanced piece of the formula is the applicable denominator. This initially comes from the IRS Single Life Expectancy (SLE) table, which estimates how many years an individual attaining a given age is expected to live. The initial denominator depends on how the beneficiary is classified (discussed later) and, in some cases, on whether the original account owner dies before or after their Required Beginning Date (RBD) when they must first begin taking RMDs (generally April 1 of the year after they reach their applicable age). For non-spouse beneficiaries, once the denominator is set, it's reduced by one each year for as long as the inherited account lasts.

Before 2020, the applicable denominator didn't just determine the annual RMD amount, it also dictated the effective lifetime of the inherited account. Because the denominator started with the heir's Single Life Expectancy (SLE) factor and then declined by one each year, the account could last as many years as the initial denominator (which the regulations effectively round up). This ability to extend withdrawals for decades, often beyond the original account owner's expected lifetime, became known as the 'stretch IRA'.

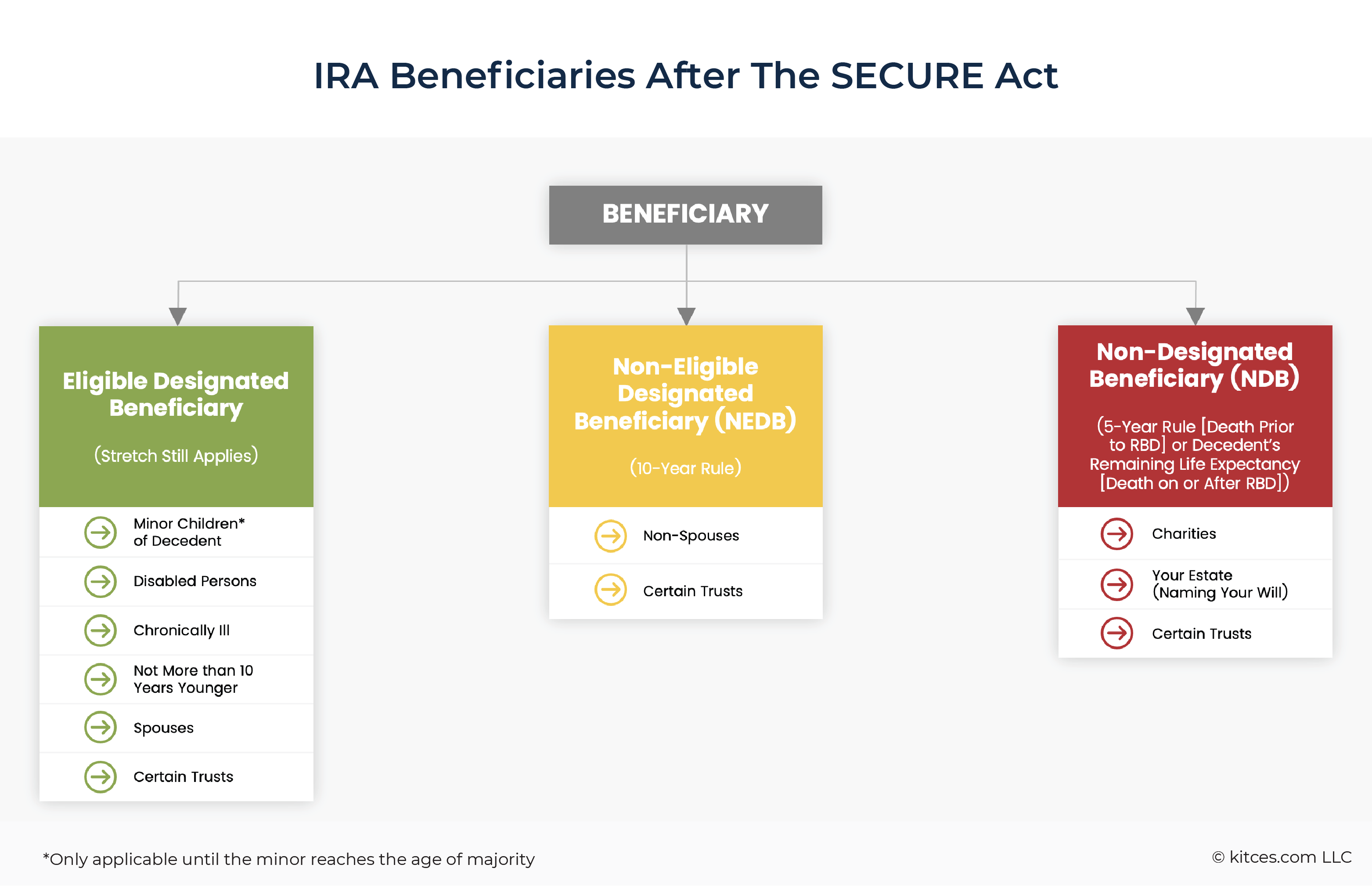

As noted earlier, however, the SECURE Act of 2019 eliminated the stretch for most non-spouse heirs. It did so by dividing designated beneficiaries into two groups: Eligible Designated Beneficiaries (EDBs), who can still use life-expectancy stretch treatment, and Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries (NEDBs), who are subject to the 10-Year Rule.

EDBs generally include disabled, chronically ill, and other persons no more than 10 years younger than the account owner. (Spouses and minor children of the account owner are special EDB cases where additional rules apply). If you are a human beneficiary and not an EDB, you are an NEDB.

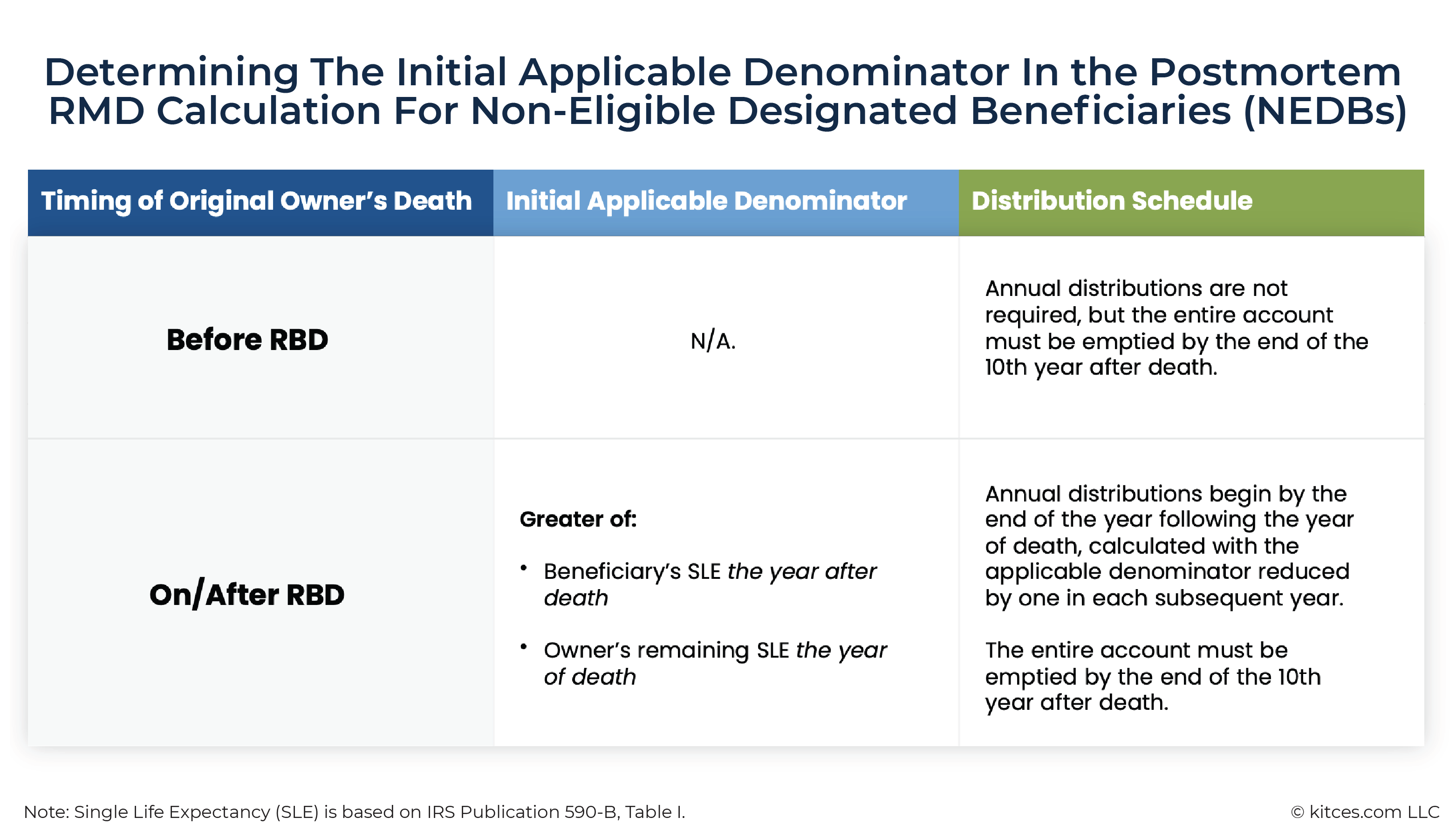

NEDBs must fully deplete their inherited accounts by the end of the tenth year following the year of the original account owner's death, regardless of when death occurred. For owners who die before their Required Beginning Date (RBD), beneficiaries are not required to take annual distributions during the 10-year period – though the account must still be emptied by the end of the period – allowing heirs to manage taxable income and cash flows with flexibility.

If death occurs on or after the RBD, though, annual RMDs must also be taken based on the SLE factor, in addition to the 10-year deadline. The applicable SLE factor for NEDBs is the greater (longer) of either the beneficiary's remaining SLE – calculated the year after death – or the original account owner's remaining SLE, as of the year of death, minus one.

Example 1: Stoick the Vast was born January 1, 1959. Before he reaches his Required Beginning Date (RBD) on April 1, 2033, he names his son, Hiccup, as the sole beneficiary for his $1 million traditional IRA. Hiccup, born in 1983, is not considered disabled (despite having a prosthetic leg) or chronically ill and will be treated as a Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiary (NEDB) at Stoick's death.

Stoick is content that Hiccup, as an NEDB, will get 10 years to deplete his large IRA. However, Stoick has a heart attack after receiving his first RMD check and passes away April 8, 2033, just a week after his RBD.

Because Stoick lived past his RBD, Hiccup won't just have a 10-year window to deplete the account – he will also have to take annual RMDs, starting in 2034. (Note: In this scenario, Hiccup would also be expected to satisfy Stoick's 2033 RMD).

Hiccup's 2034 RMD would be calculated with an applicable denominator of 35.3 – the Single Life Expectancy (SLE) of someone turning 51 the year after Stoick's death. This is greater than 14.6 – which is Stoick's remaining SLE of 15.6, (as he would have attained 74 the year of his death), reduced by one.

Each subsequent year, Hiccup will reduce this initial applicable denominator (35.3) by one in calculating his RMD. Hiccup must also withdraw the entire balance of the account by 2044 due to the 10-Year Rule, regardless of his annual RMDs.

An Unexpected Alternative: The Intentional Non-Designated Beneficiary (INDB) Strategy

As noted earlier, Non-Designated Beneficiaries – such as estates, charities, and certain trusts – were left untouched by the SECURE Act and remain exempt from the 10-Year Rule. For these beneficiaries, the maximum account lifetime is either five years if the account owner died before their Required Beginning Date (RBD), or the decedent's remaining single life expectancy – reduced by one each year and rounded up – if the account owner died on or after their RBD.

Past the account owner's Required Beginning Date (RBD), this means that unlike a Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiary (NEDB) – who (under current rules) has an inflexible 10-year time limit to empty the inherited account – a Non-Designated Beneficiary (NDB) has a variable amount of time to deplete the account, based on when the original account owner dies.

A close inspection of the IRS Single Life Expectancy table reveals that these rules create a brief period following one's RBD when an NDB's inherited account can actually have a longer maximum lifetime than that of an NEDB (i.e., 10 years).

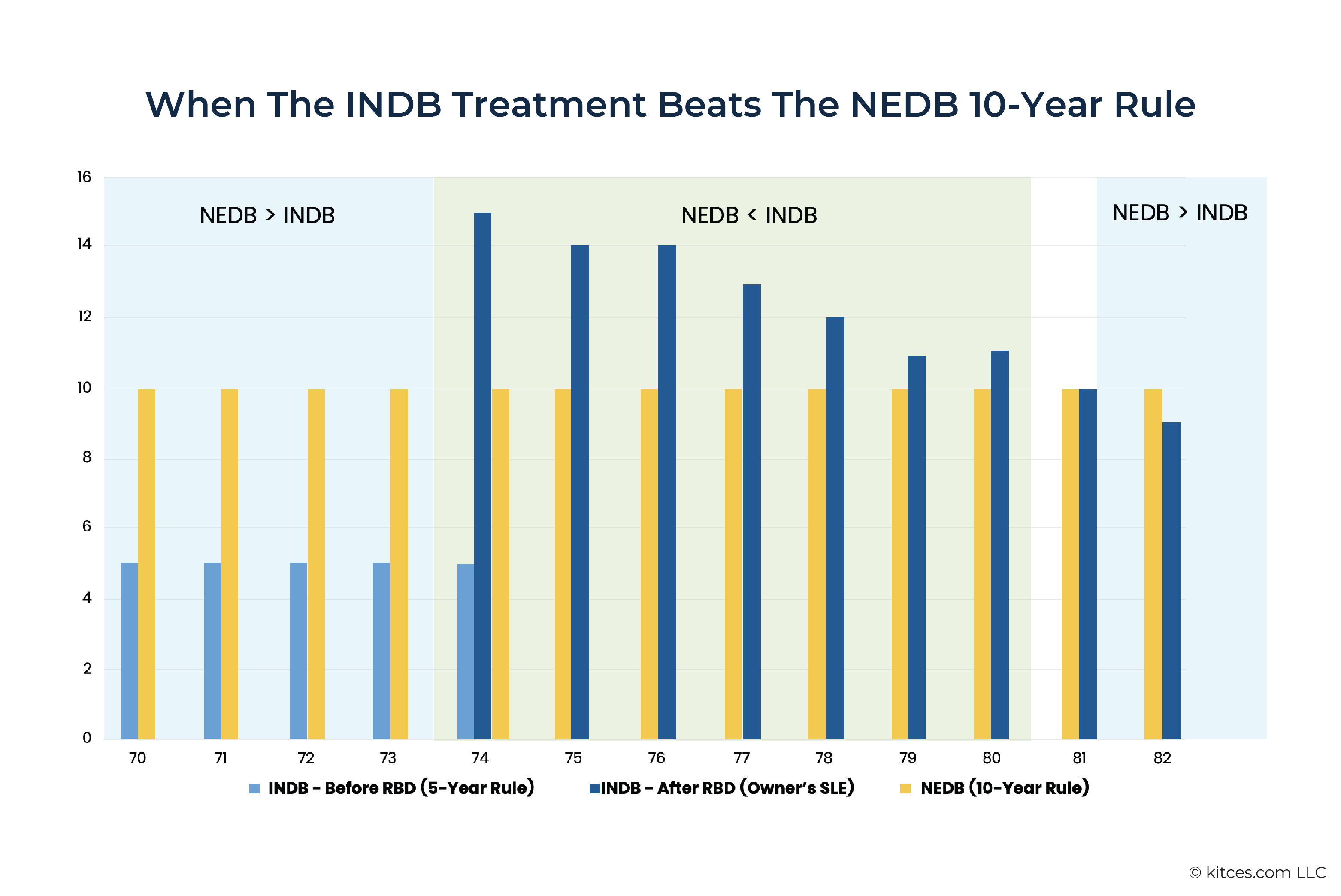

Which means the real planning opportunity comes from recognizing how the rules shift before and after the account owner's RBD. Before the RBD, NDBs are stuck with the rigid five-year rule, so naming an individual beneficiary ensures a more favorable 10-year window. But once the owner survives past their RBD, the distribution schedule for NDBs is tied to the owner's remaining life expectancy – which, in the early post-RBD years, can actually exceed the 10-Year Rule by as much as five additional years.

At that point deliberately naming careful beneficiary designations, certain kinds of trusts, or even the estate of the decedent (all which can make the heir an 'Intentional' Non-Designated Beneficiary), can stretch the payout period well beyond what an NEDB would receive. Still, as the owner ages and their remaining life expectancy shortens, NDB treatment eventually falls below the fixed 10-Year Rule – making it advantageous to revert to an individual beneficiary designation (i.e., NEDB) once again.

These outcomes are charted against the NEDB treatment's steady 10-Year Rule, below:

Example 2: Assume Stoick, from Example 1, had instead met with his financial advisor before his death. His advisor explains the difference between Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiary (NEDB) and Non-Designated Beneficiary treatment, and Stoick realizes he could potentially extend Hiccup's distribution window from 10 years to 15.

Working with his attorney, Stoick establishes a trust for Hiccup's benefit and has his advisor update the traditional IRA's beneficiary to this a specially designed trust as of April 1, 2033. Which means that while Hiccup will remain the IRA's individual (NEDB) beneficiary prior to April 1, 2033, the trust (whose sole beneficiary is Hiccup) will become the IRA's NDB after that date.

Stoick receives his first RMD check on April 1, 2033, but unfortunately dies a week later, on April 8. The trust, as an NDB, inherits the traditional IRA, stretching distributions over Stoick's remaining Single Life Expectancy (SLE) of 15.6 years, reduced by one.

Accordingly, the trust's 2034 RMD will be calculated using an initial applicable denominator of 14.6, effectively stretching distributions over 15 years (due to the regulations' rounding effect). As a result, Hiccup gains five additional years he wouldn't have had if his father hadn't met with his advisor!

There is clearly a distinct planning opportunity in the years shortly after the original account owner surpasses their Required Beginning Date (RBD) – in this case, from age 74 to age 80 – where Non-Designated Beneficiary (NDB) treatment will result in a longer account distribution timeline for beneficiaries compared with Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiary (NEDB) treatment. Interestingly, the regulations provide ways to force NDB treatment on someone who would otherwise be an NEDB.

With careful and deliberate planning, this can cause an NEDB to become what Jeffrey Levine has referred to as an Intentional Non-Designated Beneficiary (INDB) – giving heirs who would otherwise face the 10-Year Rule the chance to enjoy a longer timeline based on the owner's remaining life expectancy instead.

Nerd Note:

Prior to the SECURE Act, the stretch rules were clearly the best outcome for any non-spouse heir. Planners and estate attorneys would sometimes go to great lengths, therefore, to avoid any accidental NDB treatment. Ironically, there is now a period of time where clients and planners may prefer NDB treatment and intentionally work to trigger it!

The INDB's Potential Applicable Denominator Trap

With the Intentional Non-Designated Beneficiary (INDB) Strategy, there's a key trade-off for planners to keep in mind. The applicable denominator determines both the length of time an inherited account can last and the size of each year's RMD.

By definition, a Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiary (NEDB) will always be more than 10 years younger than the original account owner, which means their Single Life Expectancy (SLE) will always be greater than that of the decedent. This matters when the original account owner dies on or after their Required Beginning Date (RBD), because, in these situations, NEDB RMDs are calculated using the greater of the beneficiary's SLE or owner's remaining SLE (reduced by one each year). And with a larger SLE factor used, NEDBs will have smaller RMD requirements than Non-Designated Beneficiaries (NDBs) (recall that the SLE is the denominator of the RMD formula).

By contrast, RMDs for NDBs are based on the original owner's SLE, meaning Intentional Non-Designated Beneficiaries (INDBs) will always have larger RMDs than an NEDB, resulting in an accelerated taxable income stream that may offset some of the benefits of the potentially longer distribution window.

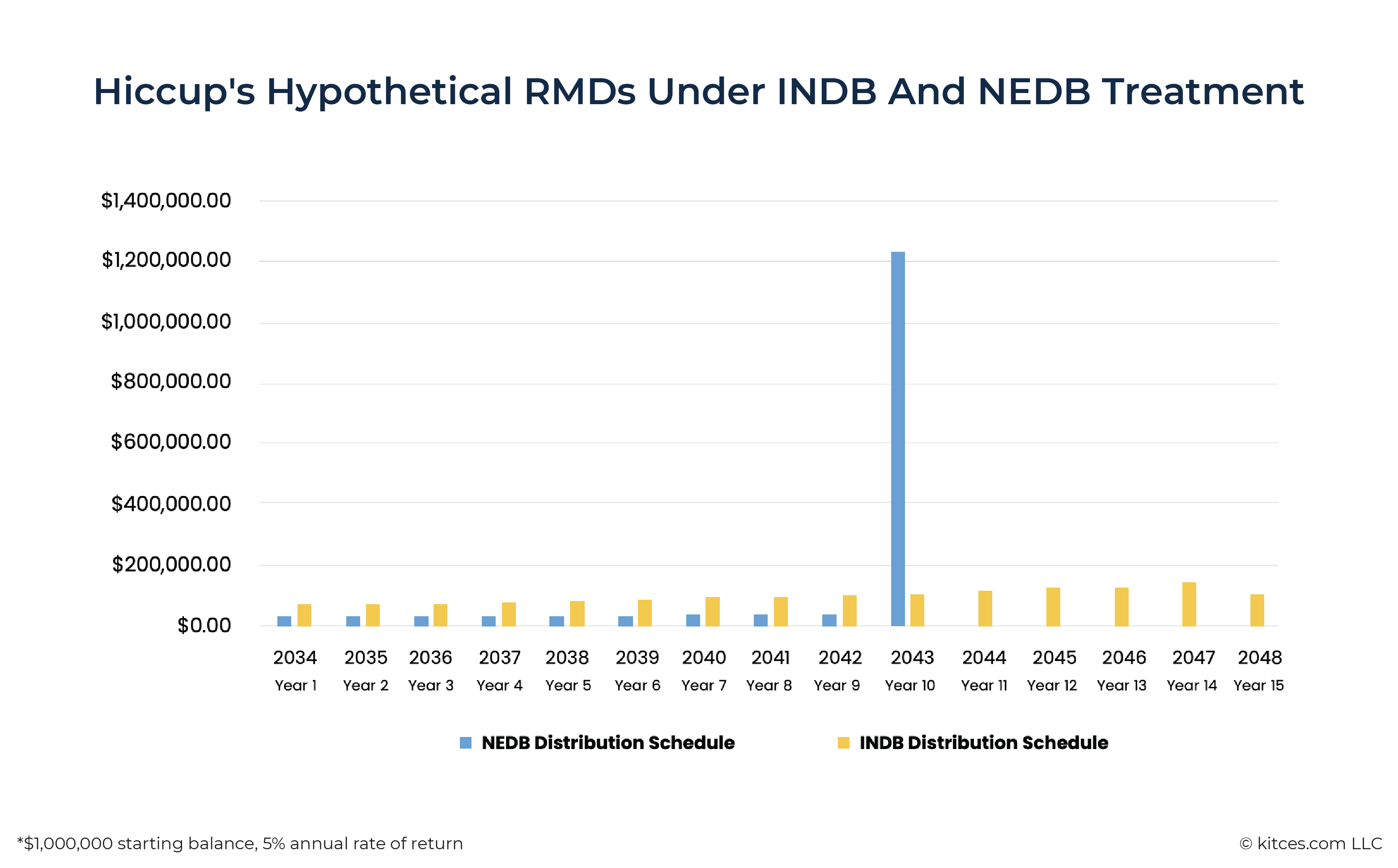

Example 3: Continuing the earlier examples with Stoick and his son, Hiccup, named as the individual beneficiary of Stoick's traditional IRA account.

Stoick passes away on April 8, 2033, one week after his Required Beginning Date (RBD) of April 1, 2033. After satisfying the 2033 RMD, the Traditional IRA balance is $1,000,000 as of 12/31/33, and Stoick's remaining Single Life Expectancy (SLE) in 2033 is 15.6, which is reduced to 14.6 (since the RMD is for 2034).

Because Stoick designated a specially designed trust (see Example 2) as the IRA's beneficiary for Hiccup's benefit, Hiccup can take advantage of an INDB distribution schedule, with a 15-year time horizon to empty the account. As an INDB, Hiccup's first RMD would be calculated based on Stoick's remaining SLE (minus one), resulting in an applicable denominator of 14.6. Which means his initial RMD would be calculated as $1,000,000 ÷ 14.6 = $68,493.15.

However, if Stoick had not established a trust to serve as the IRA's beneficiary, Hiccup's RMD would be calculated very differently. In that case, Hiccup would be treated as an Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiary (NEDB), and because his father died after his RBD, Hiccup's RMD would be calculated as the greater of his own SLE in 2034 (35.3) or his father's remaining SLE (15.6).

In this scenario, as an NEDB, Hiccup's initial RMD would be $1,000,000 (account balance) ÷ 35.3 = $28,328.61. He would be required to take annual RMDs based on his own SLE minus one each year.

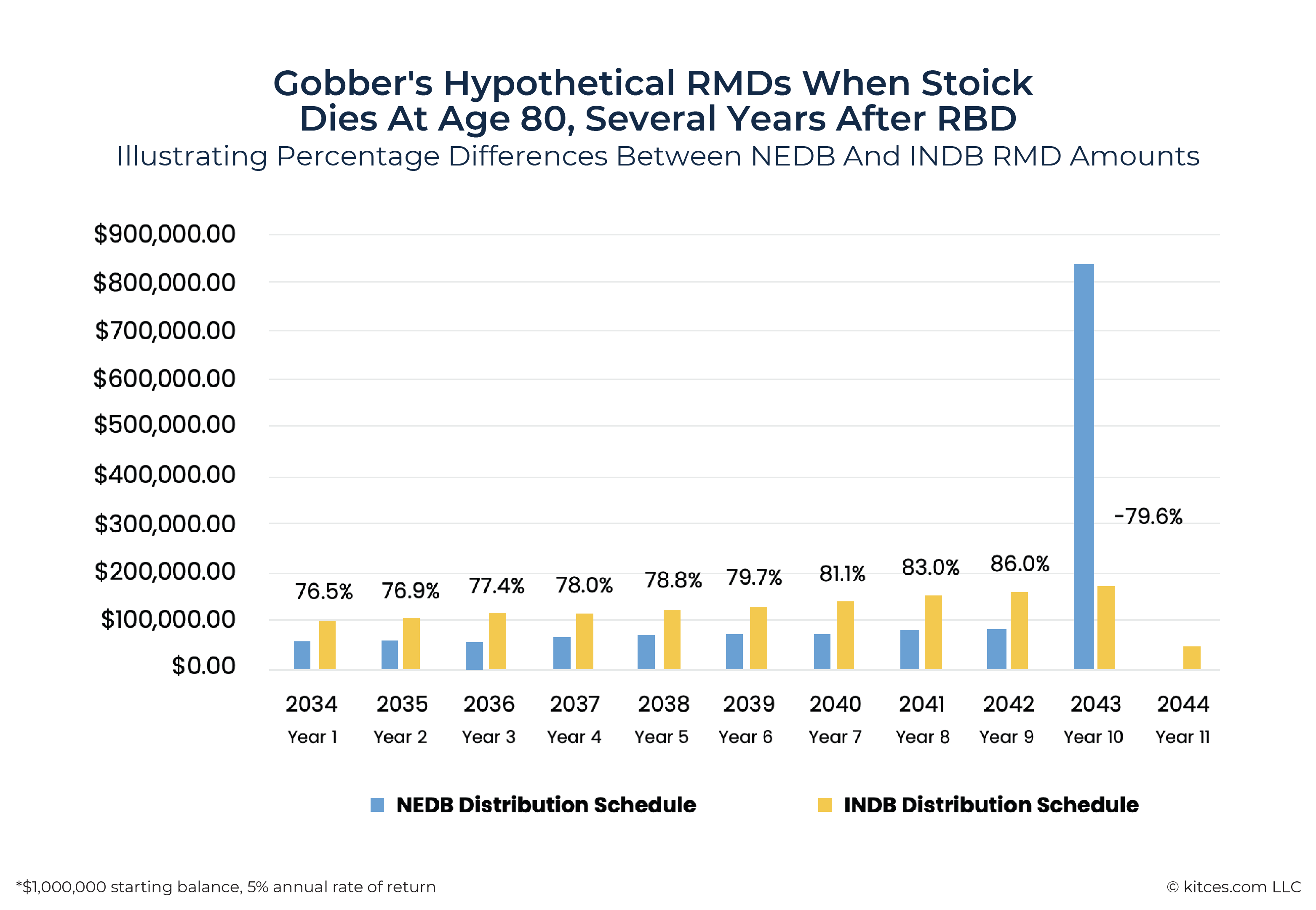

The graphic below compares Hiccup's RMDs under both approaches, highlighting the key differences in timing and magnitude of distributions:

- As an NEDB, Hiccup has a shorter 10-year timeline to empty the account, with smaller RMDs in Years 1–9 and a large Year 10 distribution to fully deplete the account.

- As an INDB, Hiccup's RMDs are spread over a longer timeline but he has larger RMDs in Years 1-9 – his first-year RMD nearly 2.5X larger than it would be as an NEDB – but, because of these larger distributions, he also has no final-year 'balloon' distribution!

Quantifying The Difference Between INDB And NEDB RMDs

If Non-Designated Beneficiaries always have larger RMDs than Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries, the question some advisors might ask is: Just how much larger might they be? Beyond rate-of-return assumptions, the answer depends on two factors:

- The age differences between the original owner and the beneficiary; and

- The timing of the owner's death relative to their Required Beginning Date (RBD).

When the owner dies soon after their RBD, the INDB Strategy can extend the inherited account's lifetime by up to five years. But as the owner ages, that extension steadily shrinks – while the required distributions during those years grow larger.

In other words, the closer the beneficiary's age is to the owner's, and the later the owner dies in the INDB window, the smaller the time horizon benefit and steeper the tax trade-off.

The following example illustrates how these differences play out in practice.

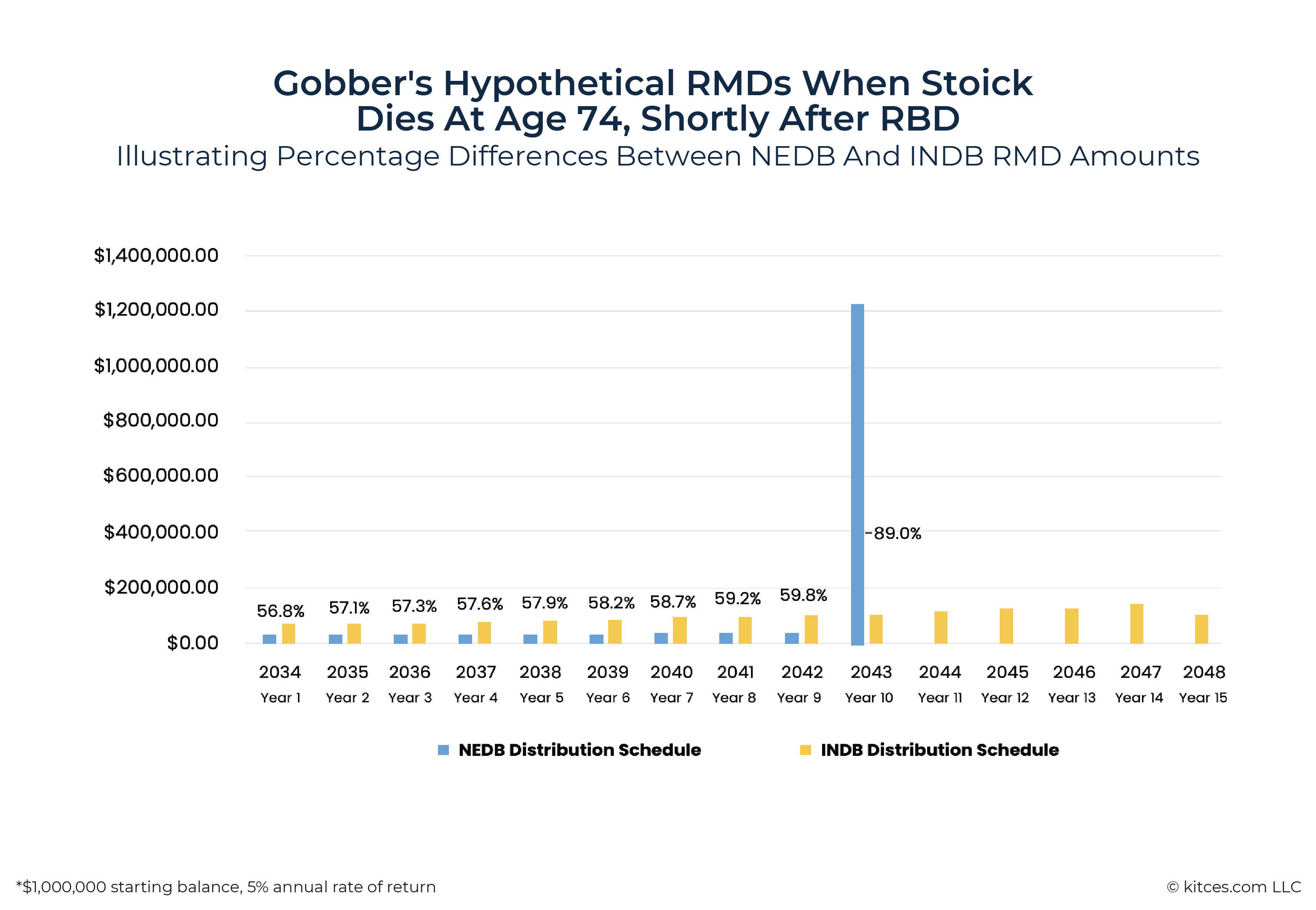

Example 4: Continuing with Stoick, (born January 1, 1959), assume he instead plans to leave his $1 million traditional IRA to longtime friend, Gobber, born January 2, 1969. Since Gobber is just 10 years and one day younger than Stoick, he misses the Eligible Designated Beneficiary cutoff by 1 day and must be treated as a Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiary (NEDB) with only 10 years to deplete the account.

Stoick visits his financial advisor, who explains the INDB Strategy's application to Gobber and describes two potential scenarios for Stoick to consider (where the advisor assumes a 5% annual rate of return for all scenarios):

Stoick Dies Shortly After His RBD.

Naming Gobber as an NEDB: If Stoick were to die a few weeks (or months) after his RBD, Gobber's RMDs as an NEDB would be based on his own Single Life Expectancy (SLE) of 22.9. His first-year RMD would be $1,000,000 ÷ 22.9 = $43,668, or 4.4% of the account balance.

Using the INDB Strategy: Gobber's RMD would be based on Stoick's remaining SLE of 15.6 (reduced by one for the first post-mortem RMD), giving Gobber five years more than the 10-year limit he'd have as an NEDB. His Year 1 RMD would be $1,000,000 ÷ (15.6 – 1) = $68,493, or 6.8% of the account balance – a 56.8% larger distribution than an NEDB's.

For RMD Years 2–9, the INDB Strategy's RMDs are projected to be between 57% to 60% higher than NEDB RMDs.

In Year 10, when the NEDB account must be completely emptied, the INDB RMD is substantially smaller than the NEDB RMD, taking only 11% of the NEDB distribution.

Stoick Dies Several Years After His RMD.

Naming Gobber as an NEDB: If Stoick were to die much later, say on December 31, 2039, and assuming the IRA balance remained the same, Gobber's RMD as an NEDB would be $1,000,000 ÷ 18 = $55,556, or 5.6% of the $1 million account balance.

Using the INDB Strategy: Gobber's RMD would be based on Stoick's remaining SLE of 11.2, giving Stoick only one additional year more than as an NEDB. His first RMD would be $1,000,000 ÷ (11.2 – 1) = $98,039, or 9.8% of the account balance, reflecting a 76.5% larger distribution than an NEDB's. (Notably, in this scenario, Stoick passes away just a day before the year he would turn 81, when he would lose the opportunity to benefit from the INDB Strategy.)

For RMD Years 2–9, the INDB Strategy's RMDs are projected between 76% to 86% higher than NEDB RMDs. And in Year 10, the INDB distribution would be much smaller relative to the NEDB RMD, taking only 20.4% of the NEDB amount.

Whether Stoick dies shortly after or several years after his RBD, Gobber would face larger RMDs as an INDB during Years 1–9 in exchange for a much smaller Year 10 distribution. Notably, the longer Stoick lives beyond his RBD, the fewer years Gobber will have to extend his distributions compared to an NEDB, which also means the first nine RMDs will also be larger.

The example above illustrates the smallest possible difference between Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiary (NEDB) and Intentional Non-Designated Beneficiary (INDB) RMDs, with the original account owner and beneficiary just barely more than 10 years apart. For other cases where the age gap between account owner and beneficiary are greater, the difference between NEDB and INDB RMDs will generally be more dramatic.

These examples highlight many of the nuances involved in analyzing RMDs for each strategy and clearly underscore the need for careful tax timing and cash flow analysis before implementing the INDB Strategy. Even under ideal circumstances for the strategy, an INDB's annual RMD for the first nine years will always be larger than under NEDB rules, front-loading taxable income.

Still, for the right clients – such as those with heirs who can absorb higher early traditional account withdrawals or, as we'll see, even clients with certain Roth employer plans – the benefit of stretching distributions beyond 10 years can outweigh the cost.

Diving Deeper Into The INDB Strategy

The INDB Strategy achieves its primary goal – namely, to extend the maximum life of an inherited retirement account – by taking advantage of a consistent planning window available to clients who have reached their Required Beginning Date (RBD), regardless of their specific RMD applicable age. While most commonly applied to traditional retirement accounts left to heirs, this strategy can also be relevant in certain cases involving Roth accounts or accounts left to late-teenage children as beneficiaries.

The INDB Planning Window For Various Applicable Ages

To this point, we've illustrated the INDB Strategy for someone with an RMD applicable age of 73. However, not everyone is subject to that specific applicable age. How does the INDB Strategy change for different birthdates, then, when applicable ages might vary?

But first, a note on the term 'applicable age': While this is often viewed as the RMD starting age, it shouldn't be confused with the Required Beginning Date (RBD), which is the actual deadline in the Internal Revenue Code and regulations for determining the distribution rules that apply to an inherited retirement account. While the applicable age and the RBD are closely connected, we'll see later that these can be separated by years for employer-sponsored plans. For now, we'll make the simplifying assumption that the RBD is April 1 of the year following the year a client attains their applicable age. For instance, revisiting the examples above, Stoick was born in 1959. He will reach his applicable age of 73 in 2032. Which means his RBD is April 1 of the following year, in 2033.

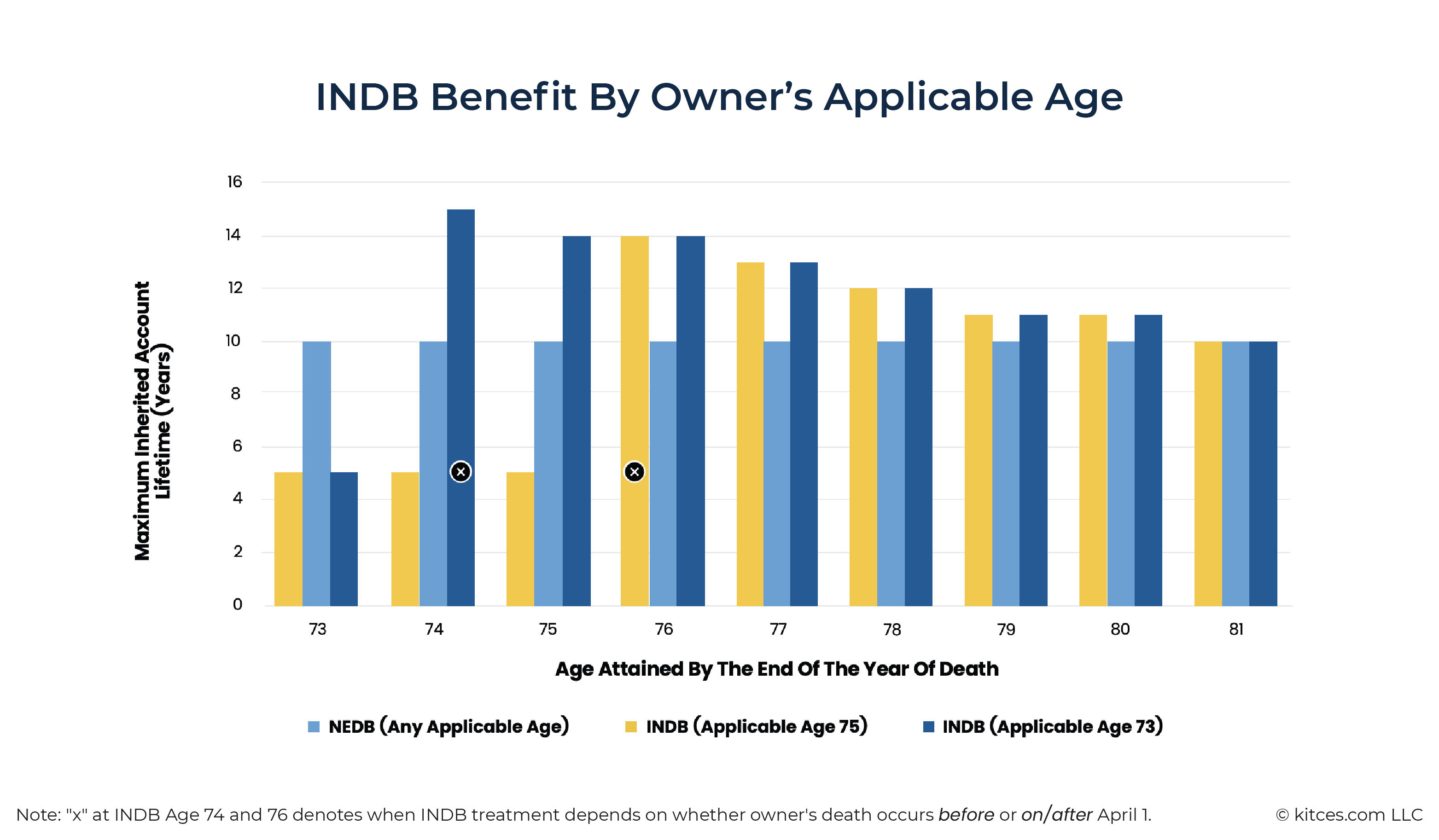

Both the SECURE and SECURE 2.0 Acts changed the applicable ages for various birthdate cohorts. Those born from January 1, 1951, through December 31, 1959, have an applicable age of 73. For those born later, the applicable age is 75. The INDB planning opportunity, naturally, starts earlier for those in the applicable age 73 cohort (because, before the RBD, the Non-Designated Beneficiary gets a 5-Year Rule instead of a Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiary's 10-Year Rule).

Because of their larger remaining Single Life Expectancy (SLE), those in the applicable age 73 cohort can give INDBs a full extra year with the inherited account (over those in the applicable age 75 group) by applying the INDB Strategy immediately on or after their RBD. Otherwise, both cohorts' INDB planning window closes after age 80, as shown below.

Nerd Note:

Clients with applicable ages younger than 73 – such as those born July 1, 1949, through December 31, 1950 (i.e., 72), or before July 1, 1949 (i.e., 70.5) – are either already in or past the window for the INDB Strategy. While the full range of these clients' planning opportunity isn't displayed on the graph, their current ages are shown.

In short, the earlier that clients apply the INDB Strategy following their RBD, the longer the inherited distribution window will be. When these clients have lower applicable ages, the INDB's impact on the maximum inherited account lifetime is enhanced. This benefit is consistent, calculable, and predictable for a given client's date of birth.

INDB's Surprising Application To (Some) Roth Accounts

While the INDB Strategy's application to traditional retirement accounts is obvious, a more subtle, unique nuance of the strategy is its positive impact on some Roth accounts.

While the general RMD rules impact essentially every retirement account, Roth accounts are subject to slight modifications. Roth IRAs are exempt from RMDs during the account owner's lifetime and Designated Roth Accounts (DRAs) – such as Roth 401(k), Roth 457, and Roth 403(b) plans – are now also exempt from lifetime RMDs.

However, the regulations create an important distinction between Designated Roth Accounts (DRAs) and their Roth IRA cousin when it comes to postmortem RMDs. Roth IRAs are always treated as if the original account owner died before their Required Beginning Date (RBD). Which means that while heirs must still follow the 10-Year Rule, they are not subject to postmortem annual RMDs.

By contrast, employer-sponsored plans that include a Roth component are more complicated. For these DRAs, the rules depend on whether the account is composed entirely of Roth dollars. If the owner's 'entire interest' in the account is 100% Roth, heirs are treated the same as if they inherited a Roth IRA: the account owner is assumed to have died before their RBD and the heir will not be subject to RMDs – just the 10-Year Rule. But if the account owner dies on or after their RBD and the account is a 'mixed-interest' plan holding both Roth and traditional balances, heirs are subject to both the 10-Year Rule and annual RMDs – applied to the entire balance, traditional and Roth alike.

Because employers weren't allowed to make Roth contributions prior to SECURE 2.0 Act, most (if not all) Roth employer plans are mixed-interest accounts. Which means that many clients who are past their RBD could benefit from the INDB Strategy to mitigate the combination of annual RMDs and the 10-Year Rule Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries (NEDBs) face in these plans.

Rolling the Roth portion of the employer plan to a Roth IRA is one way to avoid this problem, but some clients may want to leave assets in an employer plan due to lower fees, ERISA or creditor protections, or to permit 'clean' backdoor Roth IRA contributions. For these clients, comparing the shorter 10-year Roth option (and no RMD requirement) as an NEDB with the potentially longer distribution window of a mixed-interest DRA for INDBs (and annual RMDs) can be an important planning exercise.

The INDB Strategy can sometimes be one of the few effective tools for addressing the 'entire interest' rule in DRAs. In implementing the INDB Strategy with qualified employer plans, planners will also need to be mindful of defined contribution plan provisions causing a delayed RBD.

INDB For Defined Contribution Plans

As mentioned earlier, the Required Beginning Date (RBD) for an account is generally April 1 of the year following the year the original account owner attains their applicable age.

However, the Internal Revenue Code provides an exception for defined contribution plans. If the account owner continues working for an employer (or group of employers) past their applicable age, the RBD for that defined contribution plan can be April 1 of the year following their retirement.

Nerd Note:

As an exception to this exception, a 5% owner of the company does not qualify for the delayed RBD, and IRAs of any type are also never eligible.

Additionally, some employer plans require a uniform RBD for all participants – meaning all employees, regardless of ownership, must begin RMDs based on their applicable age and not their retirement date.

While delaying RMDs is often beneficial over the owner's lifetime, it does create an important consideration when implementing the INDB Strategy for employer plans. A later RBD means that the INDB Strategy's opportunity window opens later, causing postmortem RMDs to be based on a shorter Single Life Expectancy (SLE) value. Which, in turn, means the potential lifetime of an inherited INDB account would also be shorter.

For example, someone born in 1951 would normally have an RBD of April 1, 2025, putting them into the INDB planning window. But if the account in question were with their current employer and the individual planned to keep working until 2026 (age 75), their RBD would be pushed back by a year, causing the INDB window to get shorter. In that case, it wouldn't be advisable to use the INDB Strategy for that account until after April 1, 2027, when the owner's remaining SLE is 14.1.

For clients planning to work past their applicable age, this nuance creates extra complexity for the INDB Strategy within defined contribution plans. Reviewing plan documents is critical to determine whether the strategy is limited by a delayed RBD. Importantly, this highlights a key strength of the INDB Strategy: compared to other stretch IRA alternatives, the rules are predictable and can be checked directly against plan provisions, without having to rely on actuarial or complex tax assumptions.

INDB For Late-Teenage Children

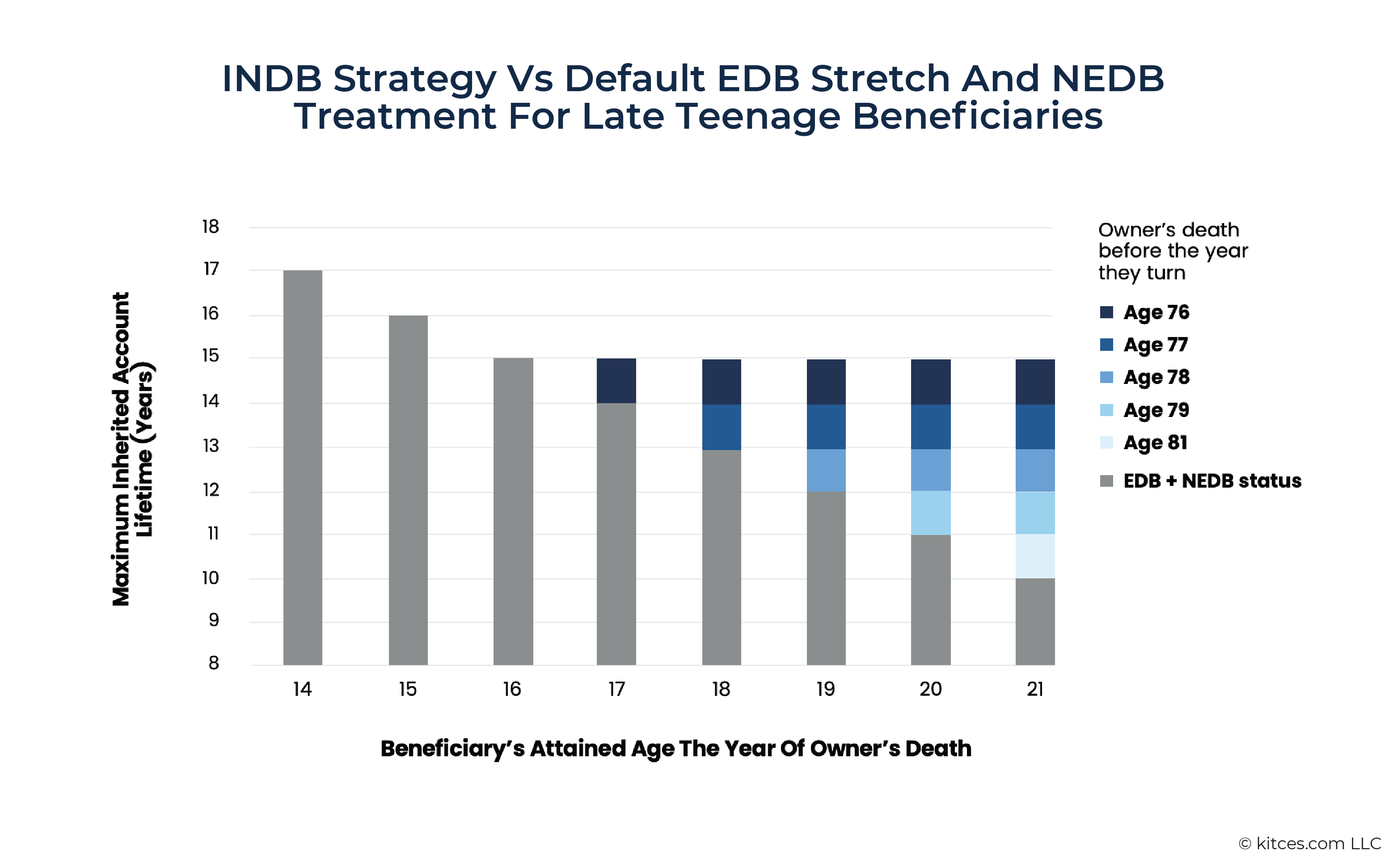

A final, unique application of the INDB Strategy is for clients with younger children. Minor children of the account owner are considered Eligible Designated Beneficiaries (EDBs), but only until they reach age 21. At that point, they convert to Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries (NEDBs) and become subject to the 10-Year Rule. (The Treasury has further clarified that “children” include biological, step, adopted, and eligible foster children.)

This creates very different outcomes depending on the child's age when the account owner dies. A newborn child could have 21 years as an EDB, plus 10 years as an NEDB – for a grand total of 31 years to deplete the account. By contrast, a child just a day away from their 21st birthday would get no EDB benefit at all and only 10 years as an NEDB.

This is where the INDB Strategy matters. Unlike other alternatives, such as CRUTs, an INDB's potential 15-year distribution window can add meaningful flexibility for heirs who are too old to fully benefit from the EDB rules but too young to enjoy as much planning leeway as NEDBs. For account owners at or just past their Required Beginning Date (RBD) with late-teenage children, the INDB Strategy can stretch distributions by up to five additional years.

The INDB Strategy's benefit, relative to a minor child's maximum account lifetime as an EDB, depends on both the age of the account owner and the beneficiary in the year of the account owner's death. Prior to the year the owner turns age 76, the INDB strategy yields a maximum account lifetime of 15 years – which is longer than the maximum duration of a 17-year-old's account (14 years, comprised of 4 years of stretch followed by the 10-year rule) and all subsequent beneficiary ages. However, if the account owner were to die at 76, the INDB Strategy would only provide an advantage to beneficiaries 18 and over, for whom EDB treatment yields 13 years or less. These and other critical age combinations are charted below.

Of course, the applicable denominator trap still applies: the trade-off for a longer distribution period is much larger RMDs in the first nine years. For many late-teen beneficiaries, though, this may not be a deal-breaker – larger distributions may already align with the child's lower income years. In those cases, the INDB can provide a way to keep the account alive beyond Year 9 and avoid the 'cliff' of a large 10th-year distribution.

How To Implement An INDB Strategy

The INDB Strategy provides both predictable and unique planning opportunities for clients looking to extend distributions for heirs across many types of accounts – from traditional IRAs to Roth 401(k) plans – and even applies to unique cases such as late-teen beneficiaries. Because these opportunities come directly from the rules themselves rather than actuarial assumptions, successful implementation requires careful attention to those rules.

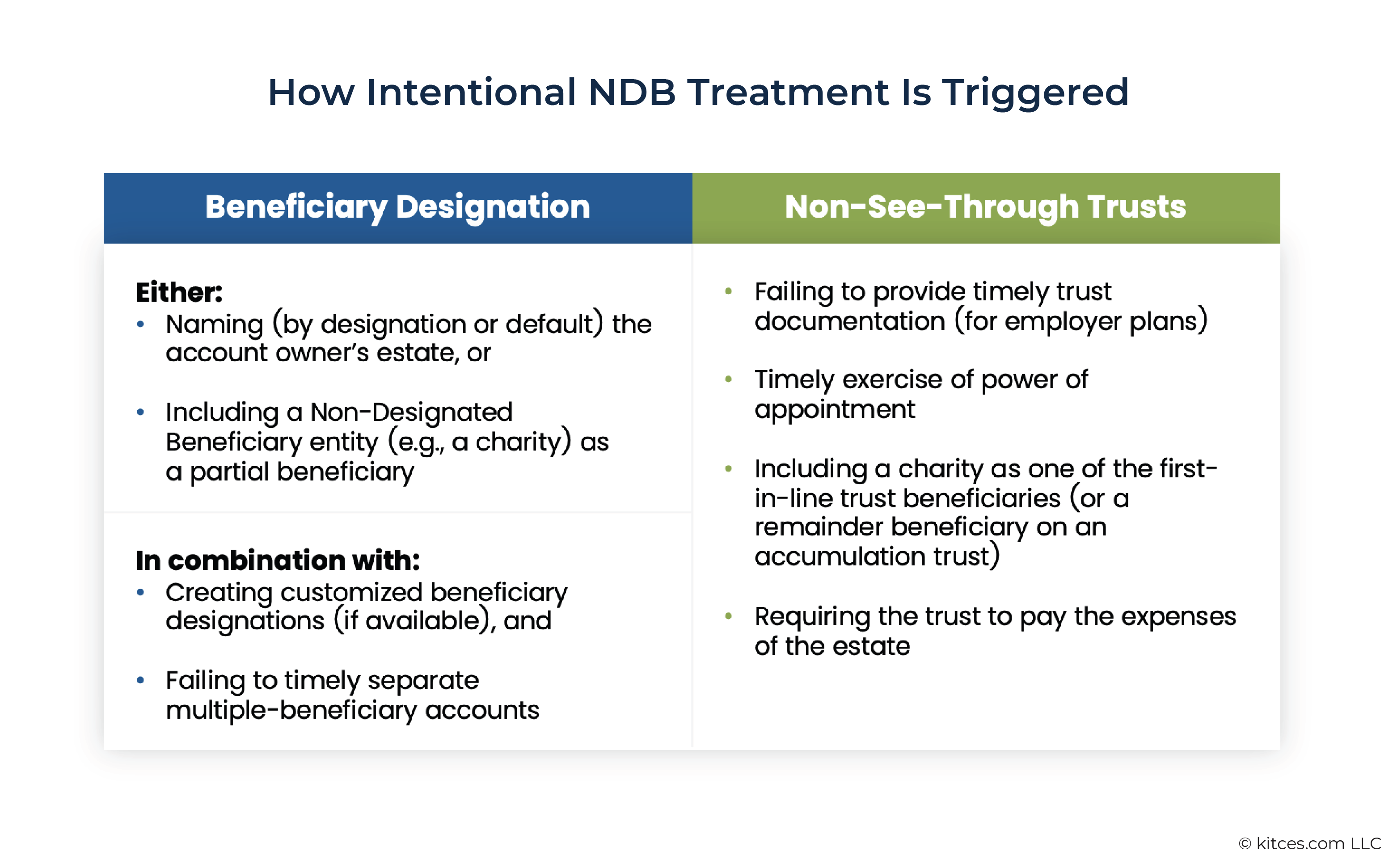

Broadly, there are two ways to trigger Non-Designated Beneficiary treatment intentionally: through the beneficiary designation itself or by using a non-see-through trust.

Each of these approaches forces an otherwise Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiary into Non-Designated Beneficiary treatment by leveraging rules defined in the Treasury Regulations, the key ingredient to a successful INDB Strategy.

Beneficiary Designations For The INDB Strategy

Beneficiary designations can be an attractive way to implement the INDB Strategy. When a client enters the INDB planning window, they can update their beneficiaries (discussed below) and, should they outlive their INDB planning window, simply revert to directly named beneficiaries. This simple process, however, can have some pitfalls clients will need to avoid.

The first, and perhaps most straightforward, way to intentionally trigger Non-Designated Beneficiary (NDB) treatment under this approach is leaving the account to the owner's estate. Not only does this avoid the complexities of naming multiple beneficiaries to trigger NDB treatment, but it also allows one document – the client's will – to govern the ultimate beneficiaries. This is often also the default if no beneficiary is listed on the retirement account. The downside, however, is that this now subjects the account to the probate process, which can be very undesirable in some jurisdictions and client cases.

The second approach involves following strict multiple beneficiary rules, which can avoid probate altogether. In short, naming just one NDB beneficiary (of any percentage) can cause all beneficiaries to be subject to the NDB's distribution rules.

Example 5: Stoick wants to implement the INDB Strategy for Hiccup. Stoick is charitably inclined and wouldn't mind leaving some of his traditional IRA to his favorite food bank.

By naming the charity (a Non-Designated Beneficiary) and Hiccup (a Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiary) as primary beneficiaries, Stoick can potentially force Hiccup into INDB treatment. Stoick can leave even just 1% to the food bank to trigger Non-Designated Beneficiary treatment!

Individuals with minor child beneficiaries should be careful with this multiple-beneficiary approach, since these rules can exclude minors – making it harder to apply the INDB Strategy in such cases.

Another pitfall is that clients must remember to update their beneficiaries twice – once to force NDB treatment during the arbitrage window, and again to switch back once the window closes. If this seems risky, some IRA custodians allow custom beneficiary instructions in writing. These non-standard beneficiary designations allow the account owner to name an NDB during the arbitrage window but revert contractually to just a Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiary afterward.

A further complication comes from separate account treatment and disregarded beneficiary rules, either of which can undo the INDB Strategy. If the inherited account is separated for each beneficiary before December 31 of the year after the year the original account owner dies, then the RMD rules for each beneficiary can be calculated separately from one another – frustrating the multiple beneficiary approach.

Example 6: Stoick, from Example 5, wants to implement the INDB Strategy for his son Hiccup, by adding a charity as a partial primary beneficiary.

When Stoick passes away in March 2035, Hiccup requests his portion of the traditional IRA be separated into a distinct beneficiary IRA (meeting all the separate account rules) in November 2036.

Since Hiccup separates the account before December 31 of the year after his father dies, his first postmortem RMD will be calculated using Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiary rules – not Non-Designated Beneficiary rules!

Disregarded beneficiary rules are intended to simplify the application of the multiple beneficiary rules but can also cause trouble for implementing the INDB Strategy. If any of the following conditions are met, a given beneficiary is ignored for purposes of applying multiple beneficiary rules:

- The beneficiary predeceases the original account owner;

- The beneficiary makes a qualifying disclaimer of their entire interest; or

- The beneficiary takes a full distribution of their entire interest by September 30 of the year following the year of death.

Example 7: Continuing the earlier examples of Stoick, assume Stoick's son Hiccup doesn't timely separate his portion of the traditional IRA. However, the food bank is… well, hungry for cash… and requests their portion be fully distributed in May 2035, shortly after being alerted of Stoick's passing and their claim on the traditional IRA.

Since the charity takes the distribution of their entire interest before September 30, 2036, the charity is disregarded as a beneficiary and Hiccup becomes the sole beneficiary, making him subject to Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiary rules.

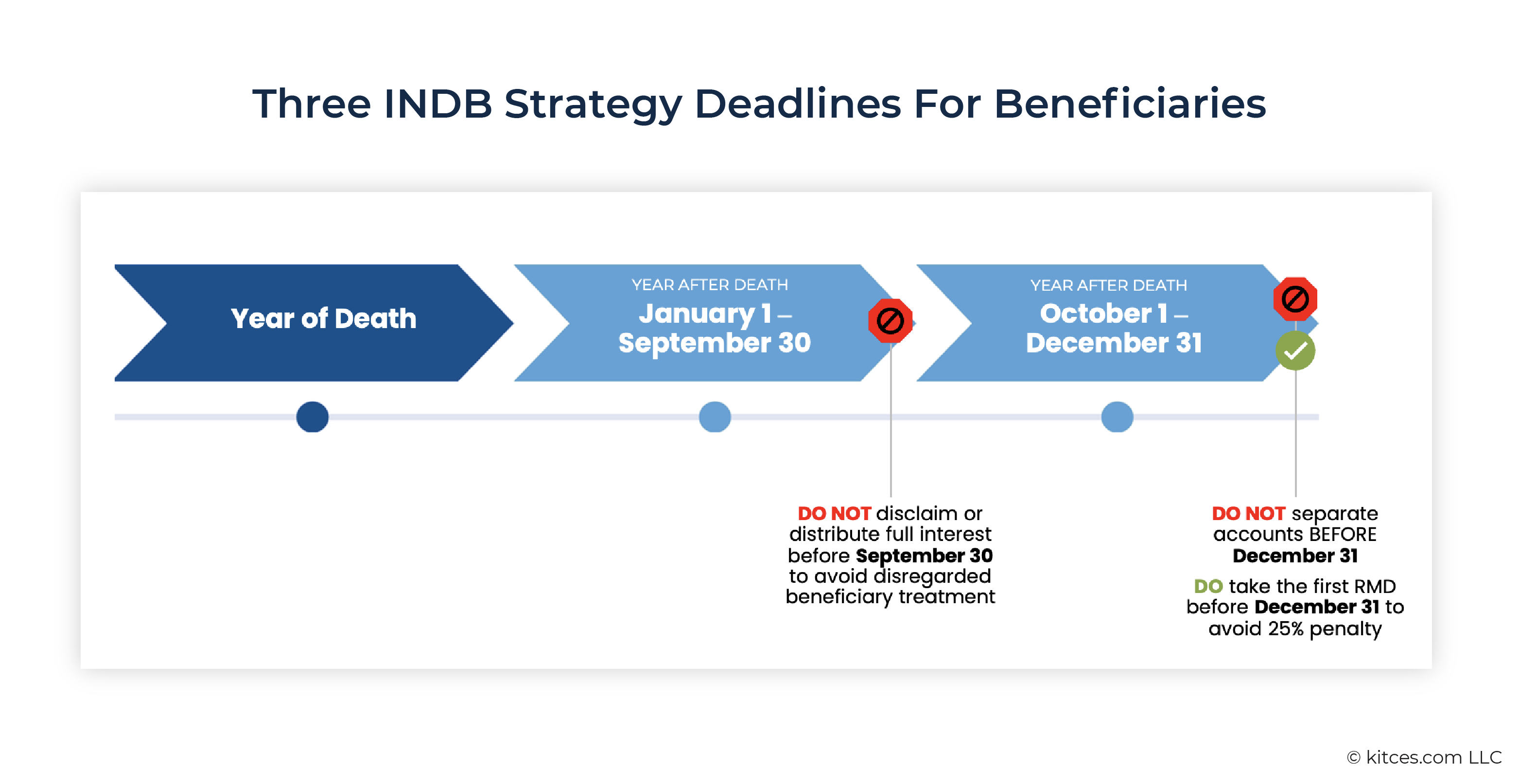

When combined, separate account treatment, disregarded beneficiary rules, and the first postmortem RMD deadline can create a trifecta of competing planning deadlines the year following the original account owner's death. In order to benefit from the INDB Strategy, beneficiaries must do the following in the year after the owner's death:

- Avoid separating the account before December 31;

- Avoid disclaiming or distributing their interest in full before September 30 to avoid disregarded beneficiary treatment; and

- Still take the first RMD by the end of the year to avoid a potential 25% penalty!

When a charity is involved (and, naturally, wants the money now!), one potential workaround is to encourage the charity to take its share after the September 30 deadline – ideally aligning with the first postmortem RMD without triggering the disregarded beneficiary rule, and allowing the individual beneficiary to delay separating their account until after December 31.

Trust Structures For The INDB Strategy

For clients who prefer to not rely on beneficiary designations alone, specially designed trusts can also be used to implement the INDB Strategy. Trusts offer the advantage of sidestepping probate and the multiple-beneficiary rules, though they require close coordination with a qualified estate attorney.

One way for a trust with Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries (NEDBs) to receive Non-Designated Beneficiary (NDB) treatment is for the trust to fail to qualify as a 'see-through' trust under Treasury Regulation § 1.401(a)(9)-4(f)(2). Briefly, to qualify as a see-through trust, a trust must:

- Be valid;

- Be irrevocable no later than the death of the account owner;

- Have 'identifiable' beneficiaries; and

- Provide timely documentation to qualified plan administrators.

If even one of these requirements is not met, the trust is treated as an NDB. For qualified plans, the simplest way to fail is to withhold timely see-through trust documentation. For IRAs (which don't have the documentation rule), it can be much harder to structure a trust to fail these requirements intentionally.

Even when a trust does qualify as a see-through trust, though, it can still be structured in ways that force NDB treatment on NEDBs. Some examples include:

- For the indecisive: Building in a 'power of appointment' feature allows beneficiaries to be added to the trust after the account owner's death. This can give heirs the ability to choose NDB treatment, without the account owner setting beneficiaries that are fixed at death. Additional guidelines for this approach can be found in Treasury Regulation Section 1.401(a)(9)-4(f)(5)(ii).

- For the charitably inclined: Naming a charity or Donor-Advised Fund (DAF) – even as just a 1% first-in-line beneficiary (or as a remainder beneficiary on an accumulation trust) – can force NDB treatment.

- For the practical: Requiring the trust to pay estate expenses can effectively make the estate a beneficiary of the trust, which again results in NDB rules applying to other trust beneficiaries.

Other considerations for clients and their estate professionals include whether a new trust is needed or an existing trust can be modified, how the trust distributes (as either a conduit or accumulation trust), and avoiding technical separate account treatment situations—such as when a trust:

- Is divided into separate see-through trusts upon the retirement account owner's death, which triggers separate account treatment; or

- Directly transfers a beneficiary's portion of the trust to an inherited IRA for the sole benefit of said beneficiary, as proposed regulations state this can also trigger separate account treatment.

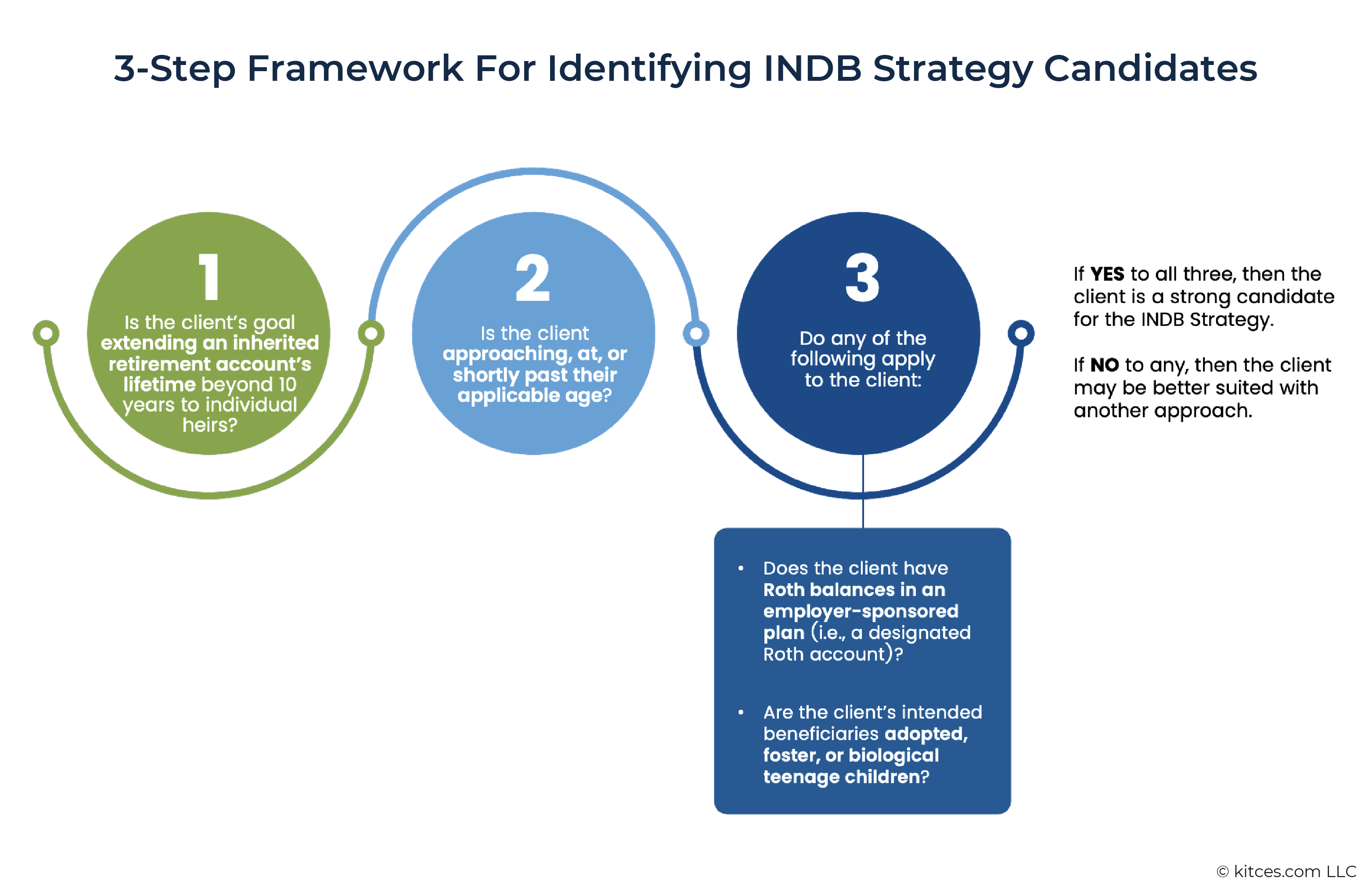

A Three-Step Framework For Identifying INDB Strategy Candidates

Whether through beneficiary designations or trusts, clients will benefit from having their broader financial team's support when implementing an INDB Strategy (including attorneys, CPAs, and adult children). A financial advisor, however, can play a critical role in recognizing when the strategy may apply and introducing clients to the fundamental concepts.

Advisors can identify potential candidates for the INDB Strategy with a simple three-step framework:

- Clarify the client's goals. Is extending an inherited retirement account's lifetime beyond 10 years a priority?

- Check the timing. Is the client approaching, at, or just past their RMD applicable age (i.e., within the INDB planning window)?

- Look for special signals. These might include Roth balances in employer-sponsored plans (subject to the entire interest rule), retirement plans with delayed Required Beginning Date (RBD) provisions, or teenage children as intended beneficiaries.

Clients born between 1952 and 1959 are in a particularly critical window to begin these discussions, with broader opportunities for implementing the strategy. For them, advisors can help weigh whether the potential to lengthen distribution periods outweighs the complexity and cost of implementation.

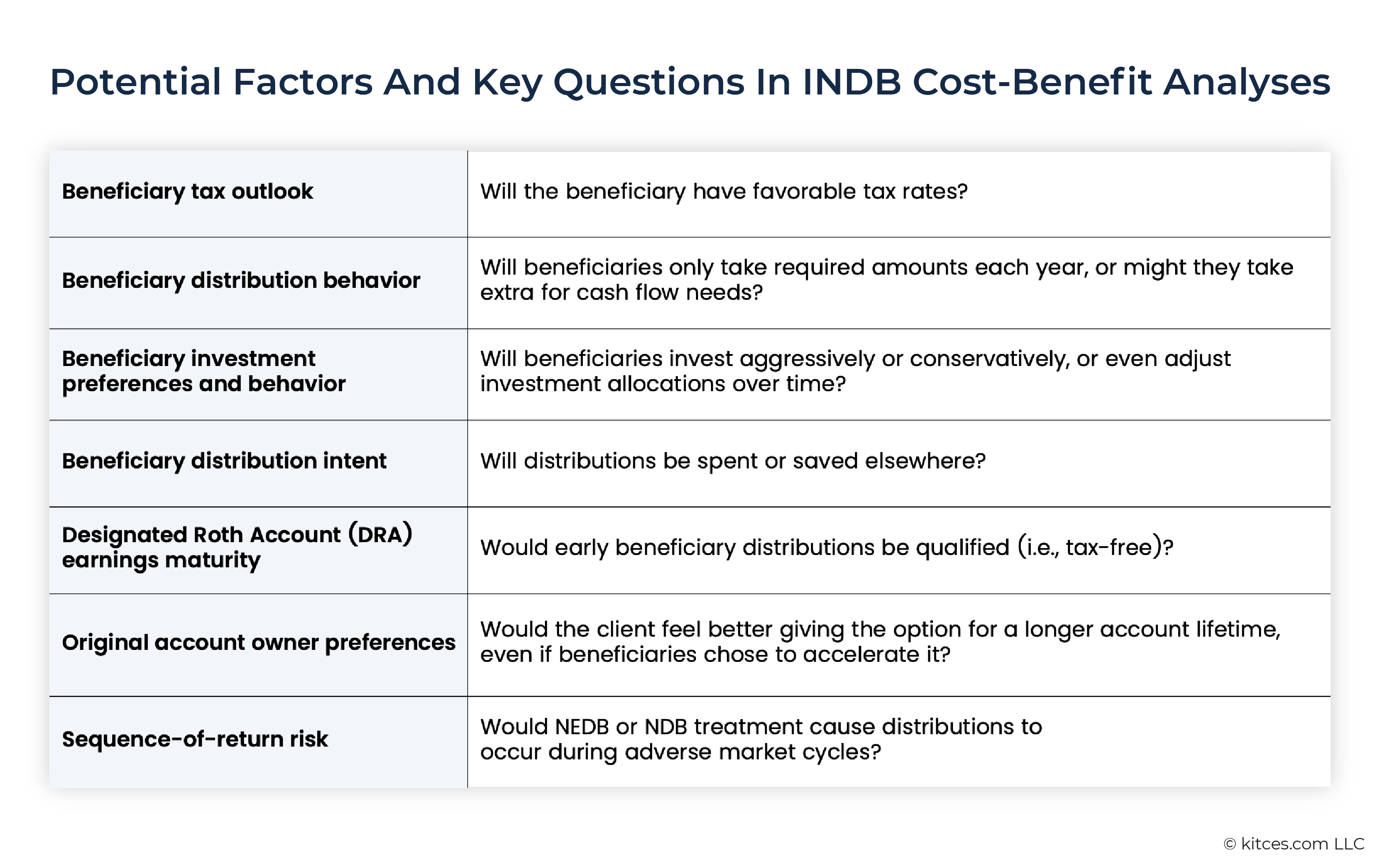

INDB Strategy Cost-Benefit Analysis

For clients interested in the INDB Strategy, education around the approach should include a cost-benefit analysis. While the strategy consistently and predictably lengthens beneficiaries' distribution schedules, it does so at the cost of higher RMDs in the early years. Advisors can add value by helping clients evaluate trade-offs with financial planning and tax analysis tools.

To perform such an analysis, advisors need to weigh both quantitative and qualitative considerations: the intended beneficiaries' tax outlook and distribution behavior, account-specific factors like Roth earnings maturity and sequence-of-return risk, and the client's own preferences, including estate planning documents, tolerance for complexity, family dynamics, and the ability of executors or trustees to carry out the plan.

As America's retirement account owners age, trillions of dollars will inevitably flow to the next generation. Some motivated clients will look for ways to maximize heirs' flexibility and extend the life of their inherited accounts as long as possible. While the SECURE Act eliminated the stretch IRA for most heirs, it inadvertently created a new – albeit contrarian – opportunity. For a defined window of time, advisors can help clients intentionally leverage Non-Designated Beneficiary treatment, allowing inherited accounts to extend beyond 10 years. In fact, for the right heirs, this INDB Strategy can provide up to 50% more time to deplete the account!

This unique strategy has practical application for clients at or near their Required Beginning Date (RBD), those with mixed-interest Designated Roth Accounts (DRAs), and even those with late-teenage children. As advisors help clients evaluate the benefit of the INDB Strategy and avoiding the potential applicable denominator trap, they can play a key role in the successful implementation of what has become a new kind of stretch opportunity – one tailored to today's post-SECURE Act environment!

Leave a Reply