Executive Summary

At the most basic level, consumers will buy a product or service when the (perceived and expected) value exceeds the cost. Whether it's to purchase a toaster, a new car, or services from a financial planner, convincing someone to part with their money in the transaction requires instilling in them a belief that the benefits in the end will be worth the pain of parting with the cost... a difficult hurdle to overcome, given that the cost is immediate and known while the benefits are only anticipated come later.

Yet as Dutch financial planner Ronald Sier points out in this guest blog post, the reality is that persuading someone to pay you for your services isn't just about making compelling points about the perceived benefits to be received. How the cost itself is perceived also matters. And since you control how your costs and expenses are presented to a prospective client, you actually have significant control regarding what your financial planning fees are compared to (which can matter a lot!), and how they're perceived.

So whether you're setting up your website for the first time and considering how to display your financial planning fees, updating your marketing materials about how your costs are communicated, or simply brainstorming how to better explain to prospective clients that the value you provide exceeds the cost, hopefully this will be helpful for you in considering not only how to discuss your value, but the importance of thinking about how you discuss your costs.

Imagine that your prospects didn’t hesitate, not even for one second, to pay your price. That it would be – in fact – a no-brainer.

Don’t believe that’s possible? Then stop here.

However, if you don’t want to leave money on the table and if you don’t want to miss my free gift at the end of this article, you might want to keep reading.

How do I know that most planners make this mistake?

Because they don’t know the psychology that goes with the setting of profitable prices for their services.

And no, the mistake is not that you charge too little (though that is a common mistake as well).

And no, the mistake is also not that most planners sit back and think to themselves: “Hmmm, what price should I pick?” And then they pull a number out of a hat and that’s it.

The mistake is to have only one price for your service.

Why? Because if you have only one price, you are not making it easy for your potential clients to decide to do business with you. You see, most of the time your prospects generally can’t understand or accurately explain why they want to hire a financial planner. The truth is, when you help them to decide to do business with you, it saves them time, money, and energy.

That’s why you want to set a smart price that will turn your offer into a no-brainer. Luckily, financial planners are by definition smart people. And, simply put, I believe smart planners want to set smart prices.

And before you wonder if I’m going to discuss a commission-based model, a fee-only based model or any other type of revenue model in our industry, I’d like to be straightforward with you on this one: I’m not. Because I believe “models” aren’t that important. In fact, what I do believe is that if financial planners serve their clients in an ethical, honest and sincere way, it doesn’t matter which type of revenue model you choose.

And if you think your customers do care about your “model”, well, you’d better read this.

What You Can Learn from Bread Machines When It Comes to Advisory Firm Pricing

Years ago I read Predictably Irrational, Revised and Expanded Edition: The Hidden Forces That Shape Our Decisionsby Dan Ariely. For the planners who haven’t read this bestseller; it’s about human irrationality and how we can predict this irrationality when it comes to decision-making.

And for those who don’t know; people are far less rational than standard economic theory assumes. Because sixty years of reseach has shown that 95% of our decisions are irrational.

That’s quite unbelievable when you read those statistics for the first time. Because most of the time we – as logical, analytical and rational financial planners – tend to believe our decisions are, indeed, rational.

But…………..they’re not. Just read this short irrational story about bread machines and I’ll show you.

You might have heard this classic story about how Williams Sonoma introduced a bread machine into the market and why they thought it would sell extremely well.

However, long story short, it didn’t. It didn’t sell well at all.

That’s why they decided to introduce a new bread machine. A bread machine that cost 50% more than the original bread machine. The first bread machine cost $275 and the new and second machine cost $429.

Guess what happened?

Sales of the first bread machine (the cheapest one) almost doubled. What happened was that people saw this as a “trade off effect”. They didn’t want to buy the most expensive option, so they decided to buy the cheaper option.

Why?

Because the most expensive option is seen as a price-anchor, making the first bread machine appear cheaper and look like “a deal”. People rationalize purchasing the less expensive option by avoiding the most expensive option.

There is only one problem with this strategy: it kills your revenues. What’s worse is that people tend to haggle the cheapest version down further.

How to Fix Financial Planning Pricing Mistakes

As Dan Ariely points out in Predictably Irrational, it’s all about relativity. People not only tend to compare things with one another but also tend to focus on comparing things that are easily comparable – and avoid comparing things that cannot be compared easily.

What do I mean?

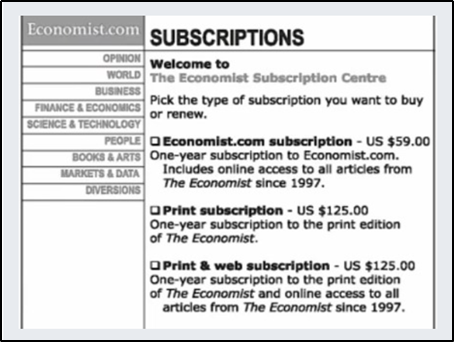

Take a look at this ad from The Economist:

The first option – the Internet subscription – for $59 seems reasonable.

The second option – the $125 print subscription – seems a bit expensive, but still reasonable.

But then, the third option: a print and Internet subscription for $125.

Huh?

Is that a typo?

If it’s true, who on earth would buy the print option alone when both the Internet and print subscription are offered for the same price?

What’s really happening is that the (very smart) Economist-marketers probably WANT people to skip the cheapest option.

As Ariely points out:

The marketing wizards know something important about human behavior: humans rarely choose things in absolute terms. People don’t have an internal value meter that tells us how much things are worth. Rather, we focus on the relative advantage of one thing over another, and estimate value accordingly.

And in this case, you may not have known whether the Internet-only subscription at $59 was a better deal than the print-only option at $125. But you certainly knew that the print-and-internet option for $125 was better than the print-only option at $125.

In fact, you could reasonably deduce that in the combination package, the Internet subscription is free!

How You Can Use This In Your Financial Planning Service

If you are like me, you now might have an idea how you could use this in your own financial planning service.

You might think, hey, I’m going to copy this. And this is how it might look:

Offer #1

Financial Planning: $2,497 plus monthly fee $97

Offer #2

Wealth Management: 1% of AUM

Offer #3

Wealth Management & Financial Planning: 1% of AUM

The first offer seems ok. The second option seems a bit expensive, but still reasonable. But then your prospect reads the third option before his eyes run back to the previous options.

“Who wants to buy stand alone financial planning, your prospect wonders, when wealth management PLUS financial planning is offered for the same price?”

The third option is in fact, a no-brainer.

What’s going on here? Most of your prospects don’t know what they want unless they see it in context. They don’t know what kind of racing bike they want – until they see a champ in the Tour de France ratcheting the gears on a particular model. They don’t know what kind of speaker system they like – until they hear a set of speakers that sounds better than the previous one.

And I hear you think: that’s great Ronald, but …

What if I’m an Hourly-Rate Planner or a Planner with a Monthly Retainer Model?

Then picture yourself grabbing a cab. Picture yourself looking at that taxi meter. Don’t you hate watching the taxi meter going up, knowing that every extra inch of the way is costing you?

Why do people hate this?

It’s because of the pain people are suffering. Not physical pain of course, but rather activation of the same brain areas associated with physical pain. The same goes for some of our revenue models.

You see, your clients are not weighing their current gratification vs. future gratifications. They experience an immediate pang of pain when they think of how much they have to pay.

So, suppose you are an hourly-rate financial planner, then try to honestly answer this question: Do you believe serving your client by the hour minimizes pain? Or is it like the taxi meter?

It’s obvious, right?

But hey, not to worry. Because you might want to consider why AOL switched from pay-per-hour Internet service to pay-per-month. And that – because of doing this – they got a flood of new subscribers.

And it’s not strange. You see, science tells us that people love to prepay for things or pay a flat rate for things.

Why?

Because it mutes the pang of pain.

Marketers have realized this for years, and they have responded with offers designed to minimize pain associated with buying their products. Netflix crushed its video rental competitors in part by its “all-you-can-watch” price strategy. Cruises have surged in popularity in part because they deliver a vacation experience for a fixed price.

In each case the marketer offers a single, relatively attractive price that removes additional pain from the buying experience.

In our industry, the single price (flat fee or all in fee) is actually higher than the amount your client spends on your advice. Nevertheless, the all-inclusive fee is likely to appeal to many of your clients.

Why?

Because it mutes the pang of pain.

So, why don’t you try to avoid multiple individual pain points in your financial planning service?

There are several options. You might want to experiment with a single-price approach for your services such as an annual fee or all in fee instead of the hourly-rate. That simpler pricing approach may boost not only sales. As some people will pay a premium for pain avoidance, profit margins may boost as well.

However, if you don’t want to do the hard work yourself, but instead, want to use a proven price-strategy that – regardless of your revenue model – works to sell the type of financial planning service you want to sell, the only thing you have to do is to answer the following question:

What is your biggest problem when it comes to the price of your financial planning service?

Please, answer this question by leaving your comment here below.

Thank you for your comment.

Let’s make financial planning matter.

One of the biggest challenges I face is that I am disclosing costs that most other models hide, so on the surface my fees seem higher than expected.

I charge a flat, annual retainer price based on the complexity of the situation, without any AUM % or commissions. When you include the fees of an AUM adviser charging 1% for a wrap account using mutual funds at 75bps or more, my 60bps all-inclusive fee would be a bargain. But for someone used to the 1% “hiding” in their statements and the mutual fund expense ratios never fully understood by many, a 60bps fee on $1M (or $6k/year) might seem like a lot.

How can I reframe it to demonstrate the value of the flat fee and the fact that in reality I am simply disclosing what many other models do not?

(FYI – here’s how I explain it now: http://iiifinancial.com/fees/)

-Elliott Weir

I am fee only financial planner. I used to charge per hour or project and I agree all the things you say above to be true. Its quite a lot of work tracking hours spent and travel time etc . In 2012 I went to an annual subscription so that fees are limited but the help isn’t. I found people ask more questions when they are not clock watching which is great as we uncover all the issues rather than not tell me and have to fix it later anyway. The problem can be more ( a small minority ) think nothing has changed so they don’t need to keep their annual review / pay their renewal. of course they don’t know what they don’t know. In some years little happens we meet once, other years life changes a lot and they take numerous appointments. I also realised there is a lot more work year one so charge more year one and less for renewals. I am not making a fortune , less actually than when I sold life insurance and mutual funds but same as an accountant might. I have added it to engagement agreement that if they don’t renew and want to return its back to the year one price and I may not have any vacancies. There’s only 1 of me in Saskatchewan. My business partner does fee only investments.

I have more problems justifying the price to people who haven’t worked with advisors before, than to those who have. I understand the anchoring idea, and was advised once to offer a “platinum” service plan that would make the next option down more attractive, but I don’t think I’ve done it effectively.

We offer a premium service and charge 1% of AUM declining with asset size. Some clients want the low cost economy pricing… But still want the premium service. I need to get better at sticking to my fee or walk away. It is hard to do once you have invested some time.

I have an AUM fee starting at 1% and it resembles an A-share mutual fund breakpoint schedule. I’ve tried it all ways: AUM fee, commission, flat rate (annually or monthly) and even allowed the clients to choose. The problem lies in the service. A client is low-service this year but a triggering event turns them into a high-service next year. Or as mentioned below they opt for the inexpensive model but expect the premium service. I’m not sure this problem will ever be resolved given human nature. We’re in an unusual business with choices on how to charge where most service businesses don’t have these choices. It’s either a blessing or a curse depending on your view.

I thought you were going to talk about how to get them to want the value of the work rather than how to sell the cost

My biggest problem is that before I explain it, prospective clients think that I will provide some service each month since I charge a flat monthly fee. I explain that they should think of it as spreading the fee over the course of the year and that usually works, but I wonder how many prospective clients turn away before I have a chance to explain it.

http://www.oliverplanning.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/Financial-Planning-Program-2015-01.pdf

To Steve’s point, it seems to me the way to get clients to want the value of the flat fee model is that they first must perceive and understand they have a problem with their current model. Then see the value in switching. That may be a challenge in this market environment when most things are up in value and fees may not seem so bad. I believe there will always be some clients willing to put the pencil to it and opt for the better value but others who just glaze over when it comes to numbers, and as long as they don’t see the fee they’ll think it’s not there (C-share). Or simply have better things to do.

I’ve had much success in explaining not only my pricing model, but those pricing models of competitors and what they can expect elsewhere. it takes the guess work out of shopping around. After reading your article I’ve been made aware of the fact that I focus on wealth management pricing and fail to explain where financial planning falls into the mix. Thanks for this insight!

As a hybrid — fee and commission — adviser, I’m trying to refine just the right language for the “I can get paid in two or three different ways” conversation. I’d prefer to have them pay a planning fee — but want to be able to pivot gracefully to AUM or commission products if they balk at the fee.

The biggest problem with advice is not having anything to compare it with. Where clients are getting a comparative service, we can show value. Where they are not getting anything or a lesser service at a lesser cost, it is difficult. We do have different pricing options, but the way we charge them is too complex – probably needs simplification.