Executive Summary

Given the intangible nature of financial advice, the reality is that financial advisors and their advisory firms rely heavily on perceived trust and their reputation in order to get clients. As a result, both advisors and their firms have a strong incentive to distance themselves from the “bad apples” of the industry.

Yet a newly released study entitled “The Market For Financial Adviser Misconduct” finds that market forces and the industry’s self-regulatory mechanisms are failing to cleanse the bad apples. As a result, 73% of "financial advisors" (though the study actually analyzed FINRA-registered brokers, not fiduciary financial advisors!) who disclose a material misconduct event on FINRA BrokerCheck are still employed a year later, despite the fact that such brokers are a whopping 5x more likely to engage in misconduct again in the future.

On the one hand, the results of the research emphasize the importance of consumers doing effective due diligence using tools like FINRA BrokerCheck or seeking out services that “vet” advisors on their behalf (i.e., find advisors and brokers with clean regulatory records), and cast a positive light on FINRA’s recent efforts (including overhauling the FINRA BrokerCheck interface, and soon requiring all brokers to include a hyperlink back to their BrokerCheck record on their professional pages/profiles).

At the same time, though, the fact that bad brokers have been able to persist so long, and find safe haven in a subset of brokerage firms that appear to have cultures that are ‘unusually’ permissive of broker misconduct - combined with the fact that the SEC improperly allows those brokers to hold out as "financial advisors" in the first place - raises the question of whether the industry’s self-regulatory mechanisms are failing altogether. To the point that, similar to another "advisor sting" study from NBER several years ago, even researchers studying financial advisors and brokers can't tell them apart. As a result, is it any surprise that the President and the Department of Labor are pushing for fiduciary regulatory change?

The Market For Financial Adviser Misconduct

Given that financial advice is an “invisible” intangible service, it’s difficult for consumers to evaluate what services to purchase and who hire. When you can’t actually try a service out beyond buying – as you can with a physical product – the consumer will inevitably fall back on evaluating other intangible qualities, like the perceived trust and reputation of the advisor and his/her firm.

This dynamic means that financial advisors and their advisory firms, as trust-based businesses, have a natural incentive towards good business behavior, maintaining their reputation, and distancing themselves from “bad apples” that may damage their reputation. Of course, this doesn’t necessarily prevent bad apples from trying to become financial advisors in the first place, but at least provides a mechanism for market forces to cleanse the industry of its bad apples over time.

Except a new study entitled “The Market For Financial Adviser Misconduct” by researchers Mark Egan, Gregor Matvos, and Amit Seru, find that the market and industry mechanisms for financial advisor “self-regulation” appears to be failing - at least when it comes to FINRA-registered brokers and RIA dual-registrants, which was the study's actual focus. While only 7.3% of all brokers have some form of misconduct in their public FINRA BrokerCheck record, the researchers found that even after misconduct occurs, only 48% of brokers lose their job with their current firm, and a whopping 44% of those are already re-employed by another firm within the same year! As a result, even after known misconduct – a regulatory action, financial settlement, or outright award of financial damages to a harmed consumer – only 27% of these “bad apple” brokers-posing-as-advisors have left the industry a year later (and 1/3rd of those, or 9% of brokers, would be expected to leave the industry annually simply due to natural turnover anyway!).

Fortunately, the researchers do find that brokers are somewhat more likely to leave and less likely to be re-employed if the misconduct incident involved an above-average settlement or damages award. And brokers who have to switch firms after a misconduct event on average see a 10% reduction in compensation.

Nonetheless, the fundamental question arises: if financial advisory and brokerage firms are so reliant on trust and reputation, why is it that 73% of brokers with a serious misconduct event remain employed as a financial advisor a year later?

Do Some Broker-Dealers “Specialize” In Brokers With Misconduct Disclosures?

Given that many brokerage firms do appear to separate from their brokers after a misconduct event, in theory those firms shouldn’t be willing to hire in brokers that have misconduct events and were fired from other firms, either. Yet the re-hiring of brokers with misconduct continues to occur.

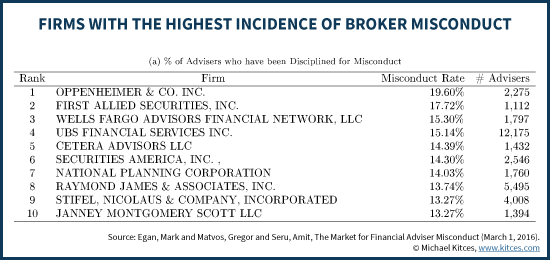

Concentrations Of Bad Brokers

As it turns out, the researchers find that the industry persistence of brokers with misconduct records appears to occur because of a small subset of firms that disproportionately hire brokers with a history of misconduct. And the research finds that these firms which “specialize” in supporting brokers with a history of misconduct are not only more likely to hire brokers who have prior misconduct, they are also more likely to have other existing brokers with misconduct records, and they are less likely to fire a broker for subsequent misconduct. Notably, the tendency for misconduct persists over time as well (firms with brokers who had misconduct in the past are more likely to have brokers with misconduct in the future).

This implication that some firms may have a culture more permissive of misconduct is further emphasized by the researchers’ finding that advisor misconduct is 50% more likely in firms where one of the owners or executives have also been disciplined for misconduct in the past (i.e., the culture of accepting misconduct comes directly from the top?). In addition, if a brokerage firm ends out dissolving for some reason, brokers with misconduct are significantly more likely to join new firms that have a higher share of other brokers with records of misconduct, as the misconduct brokres seek out their own.

Geographic Concentrations Of Broker Misconduct

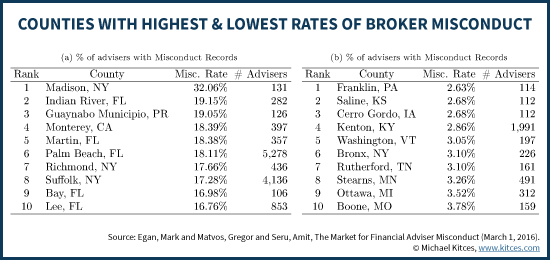

Another significant finding from the Egan et. al. study on the Market For Financial Advisor Misconduct is that it is not evenly distributed across the country.

Instead, broker misconduct is highly concentrated in the areas where, sadly, such brokers have the most “prey” to target: the frequency of broker misconduct was drastically more severe in counties that had lower education levels (a proxy for “unsophisticated” investors), higher concentrations of the elderly (a long-standing target for financial abuse), and higher concentrations of high-income individuals (more lucrative targets for misconduct).

As a result, while the overall broker misconduct rate was about 7%, and some counties were as low as 2% - 3%, many counties in California, Florida, and New York had broker misconduct rates as high as 15% - 20% (which means a whopping 1-in-5 brokers there have a history of material misconduct!).

Brokers With Misconduct More Likely To Repeat

Perhaps one of the most striking findings from the study on "adviser" misconduct is the fact that of those brokers who do have a misconduct disclosure in their disciplinary records, a whopping 1/3rd of them are repeat offenders. Which means a broker who has at least one misconduct event already is a whopping 5x more likely to be busted for subsequent misconduct again in the future. (And of course, the risk is even worse for advisors in certain geographic areas, in firms with other “bad” brokers, and if the firm’s leadership has a history of misconduct as well!)

Also notable in this finding is the confirmation that consumer complaints against brokers are not merely a matter of random chance, or an “inevitability” that any/every broker will one day suffer a complaint and be found guilty. For instance, the researchers note that when it comes to doctors, the incidence rate of malpractice is similar to that of broker misconduct; however, for doctors, more than half have had at least one instance of medical malpractice, implying that it is somewhat random and that “sooner or later, most doctors are entangled one way or another.”

By contrast, when it comes to "financial advisor" misconduct is much more concentrated. While there may be a wider range of complaints, when it comes to findings of “guilt” (or settlement damages that evidence some misconduct occurred), all the misconduct is concentrated in “just” 7% of brokers, with 1/3rd of those regular/repeat offenders. (Notably, the researchers specifically focused not just on all complaints or regulatory disclosures, which mixes in the ones that were specious or dismissed, and specifically only included the ones that involved findings of guilt and/or financial damages/awards to consumers.)

In other words, it appears there really are some “bad apples” who are simply far more prone to misconduct (and the industry is not eliminating them!). The study finds that misconduct behavior is so persistent, that brokers who had a misconduct event over 10 years ago are still significantly more likely to have another misconduct event in the future!

Does The Financial Advisor Misconduct Study Understate The Problem?

Notwithstanding all of the issues that Egan, Matvos, and Seru found in their research, it’s also notable that if anything, the study almost certainly materially understates the frequency of broker misconduct amongst those serving retail consumers.

The reason is that to do their analysis, the researchers drew every name from the FINRA BrokerCheck database – a whopping 644,277 people currently registered with FINRA in some capacity, plus another 638,528 people who were previously registered at some point in the past 10 years (the BrokerCheck data set was drawn from 2005 to 2015).

Of course, many people who are registered with FINRA are not actually consumer-facing financial advisors at all. Cerulli has previously estimated there are only about 285,000 (retail) financial advisors in total. The others who are FINRA-registered and found in BrokerCheck may be stock or bond traders working on an internal trading desk at a broker-dealer, or they may work in a division serving institutional clients rather than retail consumers, or they may be in a (registered) position of supervisory oversight. And people in such positions will simply not have the opportunity to engage in the kind of consumer misconduct that was most commonly disclosed in the FINRA BrokerCheck system – complaints like recommending unsuitable investments, or misrepresenting or omitting key facts about an investment. (Those categories accounted for more than 50% of the total complaints.)

In turn, this means that the researchers’ aggregate statistics on the rate of broker misconduct may be heavily ‘watered down’ by the inclusion of a large number of FINRA-registered individuals who not only aren’t really “financial advisors” but aren't even consumer-facing with the opportunity to engage in such misconduct. And in fact, the researchers did find that the mere reality a broker was actually working with retail investors itself was associated with a whopping 1/3rd increase in the likelihood of misconduct occurring, after controlling for other factors!

In addition, it’s notable that research from the Public Investors Arbitration Bar Association (PIABA) has previously shown that a significant number of brokers have been able to successfully expunge the misconduct reports from their FINRA BrokerCheck records – the expungement rate was a whopping 90% in the 1,625 cases in which it was mentioned between 2007 and 2011, and remained at 87.8% in the next 460 cases between 2012 and 2014. Which means those misconduct incidents were never even included in the researchers’ BrokerCheck data set, or the rate of misconduct amongst retail-facing brokers would have been even more severe!

On the other hand, this mixture of data - brokers who primarily work with the public, dual-registered brokers who also have an RIA affiliation, and broker-dealer employees who work with institutional clients, makes it impossible to effectively evaluate or compare the data on misconduct of standalone registered investment advisers (where RIAs are subject to a fiduciary standard) versus brokers (subject to a suitability standard). And the researchers' use of "financial advisors" to refer entirely to those who are registered as brokers, and even to use the financial adviser (ending with an "er") spelling from the Investment Advisers Act of 1940 (despite the fact that brokers aren't subject to the '40 Act!), further highlights their own confusion about how to evaluate the overall financial advisor community (similar to the errant NBER "advisor sting" study from several years ago, that similarly sought to evaluate "financial advisors" with a methodology that exclusively analyzed non-RIA brokers instead!).

FINRA BrokerCheck And Why Advisor Due Diligence Is Crucial

So what are the ultimate takeaways from all of this research on financial advisor misconduct?

First and foremost, it really emphasizes why services like FINRA BrokerCheck, or third-party options like BrightScope, are so crucial for doing broker and financial advisor due diligence. Because the single greatest predictor of whether a broker (or likely any financial advisor?) will engage in misconduct is whether he/she has engaged in any prior misconduct. So to say the very least, consumers should be urged to check BrokerCheck or BrightScope on their financial advisors for any public disciplinary actions, and/or go through services like Paladin Registry that vet the financial advisors for any misconduct disclosures before listing them on the site. In other words, just verifying that a broker or financial advisor does not already have a history of misconduct is actually a very material consumer protection.

On the other hand, the important value of having misconduct disclosures – including ones where the broker paid a settlement without outright admitting wrongdoing, which the researchers found was still predictive of future misconduct! – also emphasizes why PIABA is right to raise concerns about the rate of brokers expunging settlements from their BrokerCheck records. In other words, it really is important for consumers to have access to this data, and FINRA’s laxity in maintaining the integrity of BrokerCheck data may well be causing additional consumer harm. In addition, FINRA provides no means for consumers to get data about the regulatory history of entire firms, despite the fact that the researchers clearly show that some firms have a greater propensity for their advisors to engage in misconduct.

On the plus side, the good news is that last year FINRA did overhaul the BrokerCheck interface for consumers, making it easier to search for brokers and discover important regulatory disclosures about prior discipline and misconduct. And effective June 6 of 2016, FINRA Rule 2210 on communication with the public is being expanded to require firms with brokers who serve retail investors to include a hyperlink directly from their website or professional pages back to BrokerCheck. This should further help consumers follow through on the due diligence of vetting their financial advisor to identify any prior misconduct.

In addition, FINRA also announced earlier this year in its Examination Priorities letter that it will be taking a fresh look at whether and how brokerage firms maintain a culture of compliance. Given the researchers’ observations that a subset of firms seem to “specialize” in brokers with misconduct records and have a culture of tolerating such behavior, in theory a crackdown on the subset of brokerage firms that have been especially accomodative of misconduct could actually have a disproportionately positive effect on cleaning up the industry overall. (One even wonders if FINRA made broker-dealer culture a priority because they had been warned that the results of this research study were looming?)

A Failing Of Financial Advisor And Broker Self-Regulation?

Notwithstanding the progress that has been made, though, it’s sadly still notable that it took FINRA all the way until 2015 to finally revamp its web-based BrokerCheck system into a more usable format for consumers in the first place, and at the same time the painfully outdated “anti-testimonial” rules have made it very difficult for third-party advisor review sites to gain traction, either. In other words, FINRA both maintains a near monopoly on the ability to produce meaningful consumer data on broker and advisor misconduct, and has been slow to improve its quality and had trouble maintaining the data’s integrity from specious expungement requests. Is this an outright failing of the industry’s self-regulatory structure, where FINRA's board of directors is comprised of the very broker-dealer firms about which it is failing to provide transparency?

More generally, the low suitability standard from FINRA has made it even easier for both bad brokers and the broker-dealers who accommodate them to persist. Even though many firms are quick to fire brokers who engage in misconduct, and not hire those with a history of misconduct, the fact that a small subset of firms have become a “safe haven” for bad brokers is allowing consumer harm to perpetuate. In the meantime, FINRA continues to be slow in lifting its "Conflicts of Interest" standards for brokers, even as it makes pushes to expand its jurisdiction to examine RIAs as well. And of course, this still ignores the fact that brokers who are barred from FINRA have for years simply been going out to get a state insurance license instead, and just continue their misconduct in the form of abusive sales practices with fixed and equity-indexed annuities! In other words, the problem of financial advisor bad apples isn’t just a failing of FINRA, but a broader failure to control the term “financial advisor” in the first place, and instead allow it to be used interchangeably with “salespeople” in a wide variety of product sales channels.

And of course, in the end the process of vetting a financial advisor should be about more than just identifying prior harm and misconduct; instead, it should be about identifying the skillsets, credentials (and supporting continuing education), and other characteristics that increase the likelihood it will actually be a good financial advisor (such as the CFP Board’s recent “Certified = Qualified” public awareness campaign). And while the “Market For Financial Advisor Misconduct” study makes a compelling case that big data can be used to prospectively identify areas of greater risk (e.g., advisors at certain firms with a history of misconduct, or geographically located in certain counties with more ‘at-risk’ population), the industry recently fought back FINRA’s own CARDS big data initiative.

As a result of these challenges, the fundamental challenge remains: the brokerage industry, and the financial advisor community at large, is failing to clean up its own bad apples, and poor transparency and tools for consumers to identify brokers with a history of misconduct has only exacerbated the issue. Fortunately, recent efforts by FINRA, including an overhaul of BrokerCheck and coming mandates to increase its visibility, should at least partially help the situation. Nonetheless, given the industry’s general failing in effective self-regulation, as illustrated in the “Market for Financial Adviser Misconduct” study, is it any wonder that momentum has grown for a new fiduciary regulatory solution from the Department of Labor that may finally force broker-dealers to engage in some real change, and that it's actually the fiduciary financial planners leading the charge to lift up the standards for all brokers and financial advisors?

So what do you think? Has the "Market For Financial Adviser Misconduct" study highlighted a gap in the industry's self-regulation of brokers? Was it appropriate for the researchers to characterize the results as "financial adviser" misconduct instead of broker misconduct? What should be done to crack down on the subset of advisory firms that are operating as safe havens for the bad apples? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!

Question: What constitutes misconduct? I know an adviser with a sterling record that tried to open his own RIA. He was unaware that his current RIA had failed to properly register him as a IA representative of the company with the state that year and pay the $20 state fee. When he tried to register his new firm with the state the error was discovered. The state took enforcement action against the adviser and he was forced to settle with a reprimand and a big fine or they would not have allowed him to open his RIA. This action is still on his record 16 years later. An administrative error made by his company without his knowledge as it is the company’s responsibility, not his, to register RIA reps. I would hardly call this misconduct of any kind but if someone searches, that is clearly what they infer.

The study’s definition of “misconduct” included only 6 of the 23 categories of potential disclosures in a broker’s CRD record – in essence, they were all scenarios where either the Regulator had a final enforcement action against the broker, the broker left the broker-dealer with allegations pending, there was a customer dispute with a paid settlement or an outright award/judgment, or there was a civil suit for which the broker was found guilty.

Notably, this does mean there are a SIGNIFICANT number of FINRA BrokerCheck “disclosures” that would not have constituted misconduct in the context of this study, but will show up as disclosures in a consumer search.

The point of the study wasn’t merely that “BrokerCheck disclosures” matter, but that actual findings of misconduct that led to consumer damages matter. Though the study did find there was still SOME correlation between ‘other’ disclosures and misconduct as well (but far less than outright misconduct as a predictor of subsequent misconduct).

– Michael

I think that this study uncovered only the tip of the iceberg. I think that most misconduct either never gets revealed, i.e., clients never figure out what’s being done to them, or it gets revealed, i.e., clients figure it out, but do not file complaints or claims.

The industry incentivizes, i.e., rewards, bad behavior. It’s Pavlov’s dogs. Stimulus–>Response. If you reward them for screwing their clients, they will screw the clients. You WILL get the behavior that you incentivize. Did you read the New York Post article about the Morgan Stanley contest that incentivized the sale of securities collateralized loans. Within 1.5 years of being a Smith Barney small business owner client documents with a bunch of SIGN HERE sticky notes was sent to me. It was for a $400,000 line of credit for the purchase of inventory. I had never requested this. I had never even suggested it. Yet I receive completed paperwork with encouraging SIGN HERE sticky notes plastered all over it. What contest was incentivizing this bad behavior? I note that Smith Barney is now under the name Morgan Stanley. I think that it’s time that client moles start infiltrating these firms and exposing them and the sales forces/relationship managers for what they really are–client product penetrating machines.

One important point. As mentioned, the study defines “misconduct” as including terminations after unproven allegations by the firm. Unproven, unsworn allegations. That is a huge problem. Unfortunately, some firms, or their managers, terminate brokers for a variety of non-misconduct issues, and then indicate misconduct on the broker’s record in order to delay his registration at a new firm. Those allegations are never proven in a court or before an arbitration panel, and are included in this study as misconduct.

Further, included in that 7% is any broker, regardless of his registration status, who ever had a customer case that was settled in the last 10 years, including those who are no longer registered or active in the industry. For example, the broker who had a $5,000 customer settlement over 11 years ago, in 2005 is included in that group.

Think about it – 7% of 1.2 million people who had a complaint over the last 10 years is a pretty good track record, given the rampant incidents of over-reporting of “misconduct” that does not exist in any other industry.

Mark Astarita – http://www.securitieslawyer.us

The industry is a dark box. Bad behavior is rampant. Many clients never figure out that they are being conned and when they do they are too embarrassed to report it, don’t have the time to hassle with it, or want to put it behind them and get on with their lives. Who can blame them? FINRA arbitration is a kangaroo court; it’s a black box.

Mark,

Understood that one of the study’s categories was a termination after “just” an allegiation. At the same time, the authors DID find that such “misconduct” was in fact correlated with subsequent misconduct as well.

Certainly not every complaint termination is associated with actual misconduct, just as not every broker who engages in serious misconduct does it again in the future.

But the study does make the point that an allegation serious enough for the broker-dealer to terminate – rather than fight – apparently does have at least some predictive value.

This isn’t meant to suggest that the whole FINRA reporting and tracking of misconduct couldn’t use some significant tweaks to protect those who are genuinely innocent though.

– Michael