Executive Summary

Traditionally, people tend to think of their estate as comprising one big 'pot' of assets, focusing on the sum of all the assets rather than on each individual asset itself. Consequently, when in estate planning, thinking about how to divide their assets after their death, they often aim to simply apportion the whole pot among their beneficiaries, without regard to the nature of each individual asset.

Although the 'one big pot' mindset might be the simplest approach to estate distribution, it may not be the one that results in the most wealth being passed down or the most equitable distribution of assets between each beneficiary. That's because, depending on the beneficiaries' individual situations, different types of assets will have different tax characteristics when inherited, which might make particular assets better or worse for different beneficiaries depending on their tax circumstances. For instance, if a traditional IRA is split equally between 2 beneficiaries in different tax brackets (or in different states of residence with different state tax rates), the beneficiary in the higher tax bracket will pay more tax on their share of the IRA (and consequently receive less on an after-tax basis) than the other.

Consequently, it can be beneficial to approach estate planning on an asset-by-asset basis to make the process more equitable and tax efficient by accounting for the disparity of income tax treatment of the different assets in the estate (and the unequal tax circumstances of the beneficiaries who will inherit them). For instance, an estate with a mix of pre-tax retirement assets (taxed upon withdrawal by the beneficiary) and nonqualified assets (which typically receive a step-up in basis and have fewer tax consequences for the beneficiary) can be allocated such that the pre-tax assets are left to the beneficiary with a lower tax rate and the nonqualified assets to the beneficiary with a higher tax rate. Then not only will each beneficiary receive the asset that results in the highest after-tax value to them, but the total after-tax value of all the assets passed down will be higher than if they were each simply divided equally between the beneficiaries.

Notably, an asset-by-asset approach to estate planning isn't 'just' about drafting documents like wills or trusts; it requires full knowledge of the client and the details of their (and their beneficiaries') financial, tax, and overall life circumstances. Which leaves financial advisors in a unique position to aid in the process of deciding when an asset-by-asset approach will result in sizable tax savings for the estate and beneficiaries and when a traditional 'split-the-pot' approach would make more sense. As while estate attorneys may meet with the client only rarely (if at all) after the actual estate documents are drafted, advisors usually have regular recurring meetings with clients, giving advisors the opportunity to keep up with the family's dynamics and tax situations and recognize when a change would be warranted.

The key point is that, just as clients have different planning needs, goals, and tax circumstances during life, the same applies to their beneficiaries and assets after they're gone. Incorporating the impact of taxes in the financial planning process to help clients keep more of what they've earned in life makes as much sense as using the same approach in the estate planning process, by considering what happens from a tax perspective after the assets reach their intended destination. And, by offering a more equitable distribution scheme for their beneficiaries, advisors can help their clients ensure they pass the most (after-tax) wealth to the next generation!

I once ran into a scenario where an advisor's client was preparing to inherit assets – including IRA funds – from a recently deceased relative whose estate consisted of substantial pre-tax retirement assets (in excess of $1 million) that were flowing through the probate estate. There were multiple underlying beneficiaries (aside from the client) set to inherit from the decedent's estate after the administration period was completed by the attorney.

The advisor was rightly concerned about the rules surrounding IRA funds left to an estate and that the payout period would be over 5 years rather than the usual 10 years under the SECURE Act. After covering the rules, the advisor had been planning to discuss the proposed distribution scheme with the attorney. A few days later, though, the exasperated advisor called back and informed me that any proposed tax deferral was now lost because the attorney had directed the executor to withdraw the entire balance of the IRA into an estate account (thereby realizing all of the previously deferred taxes). The attorney's reasoning? "This makes it easier".

It is not uncommon for the lure of simplicity to overtake tax efficiency during the estate planning process (often at the beneficiaries' ultimate expense). Of course, it is almost always the case that the more complex the tax planning, the higher the cost and the more laborious the administration. However, rather than taking a simplistic approach as a rule of thumb, there should be a cost-benefit analysis performed (even if only at a high level) to determine the ultimate result of each increasingly complex approach to the plan.

Additionally, an estate plan is often simply viewed as the formal legal documents that comprise the estate plan rather than as a comprehensively considered strategy that led to the documents that helped to implement that plan. As such, it is not uncommon for estate planners to see a client's estate as one big 'pot' to be divided for beneficiaries, disregarding all of the various tax attributes of the assets funding the plan and the income situations of the beneficiaries set to inherit from the estate.

However, taking an "asset-by-asset" approach – where the post-inheritance tax impact of individual assets, strategically allocated to specific beneficiaries, is considered – can create an estate planning strategy designed to save taxes. While this approach can optimize the overall wealth passed on to beneficiaries, it's not a strategy that necessarily makes sense in every situation. Which is why it's important to be cognizant about not letting the ‘tax tail wag the dog’ and to understand the risks and ongoing maintenance involved with asset-by-asset estate planning. Being able to identify client estates that warrant such an approach to planning gives advisors a way to offer these clients a potentially better strategy than simply dispersing all assets in equal percentages to their beneficiaries.

The Current Estate Planning Mindset

When creating an estate plan, clients often have a general framework of the beneficiaries of their estate based on the apportionment of the entire estate as a whole, rather than taking into consideration each individual asset. For example, a client may have an estate consisting of a primary residence, multiple retirement accounts, a non-qualified brokerage account, and life insurance. Typically, a client will not be focused on the unique tax attributes of each asset, but rather on ensuring there is an equitable distribution of the estate based on the fair market value of the total estate.

Certainly, clients may decide they would like to bequeath specific assets to specific beneficiaries (i.e. a primary residence or closely held business interest to a certain child). However, such decisions are often related to personal circumstances rather than a conscious decision based on tax efficiency. This mindset of an estate as 'one big pot' of assets to be divided can distract from key opportunities to not just pass the most amount of wealth possible to the next generation, but have the most amount of wealth retained by the family net of taxes.

Why This Mindset Has Dominated Planning

This 'one big pot' mindset when it comes to considering the assets in an estate likely derives from a desire for simplicity and avoidance of conflict when dividing the estate. Of course, anytime an estate is intended to be divided equally, dividing each individual asset equally is the most logical and simplistic approach to accomplish an "equitable distribution".

Many clients view this as an equitable approach in terms of the pre-tax fair market value being delivered to each beneficiary. For example, if a decedent had 2 children as beneficiaries and left behind an asset with a $500,000 fair market value, then 'equitable' (without more context) would mean distributing $250,000 to each child. However, when digging into the details of an estate, the term "equitable" can be a moving target, especially when taking into account the type of asset and the income situation of each beneficiary.

How The 'One Big Pot' Mindset May Actually Reduce The Total Wealth Received By Beneficiaries

What is often overlooked in the planning process is the proportion of the asset that could go to the government after the beneficiary has realized all income associated with the asset that had been built up before death. While substantial planning can be done to avoid taxation from an estate tax (Federal and/or state) perspective, a portion of those savings could be lost if what happens after the beneficiaries inherit the property is not properly assessed.

Accordingly, when the assets that make up an estate are heavily weighted toward accounts that have not yet been taxed, the beneficiary will take on that liability. Then, if beneficiaries have disproportionate income tax rates on realized income, some beneficiaries may end up paying the government far more than other beneficiaries after inheritance.

Of course, logically, this may not result in a lot of hard feelings as the high-income earner is likely (but certainly not always) in a better financial situation than someone in a lower tax bracket. However, it does mean that the total wealth that is ultimately passed to the family is lower than if the beneficiary in the lower income bracket had taken on more of the income from the estate. There will be an example later that models this.

The Different Tax Statuses Of Assets That May Pass To Beneficiaries

The types of assets comprising a decedent's estate (and the proportion thereof) can vary wildly. Let's take a look at each category of asset and the taxation of the asset to the beneficiary from an estate planning perspective.

Non-Qualified Assets

Non-qualified assets are assets that do not have any special tax status under the law to provide for income tax deferral. This category could comprise many asset types such as individual brokerage accounts, real property, cash, savings accounts, etc.

In most instances, non-qualified assets will receive a basis adjustment (commonly referred to as a "step-up in basis") at death.

Nerd Note:

The term "step-up in basis" can be misleading and create a false sense of security or, worse, result in improper planning. Section 1014 of the Internal Revenue Code sets forth the rules relating to the basis of property acquired from a decedent, which can result in either a "step-up in basis" or a "step-down in basis".

Importantly, the beneficiary has no choice if the basis is adjusted; the basis is automatically adjusted – either up or down – by operation of law at death. Therefore, using the blanket term "step-up in basis" disregards that, when a person dies with an asset that has a higher basis than the current fair market value, the basis will get stepped down and the beneficiary will not be eligible to take the loss.

So, the term "basis adjustment" is a more accurate way to generically refer to what happens to basis of a non-qualified asset at the death of the owner!

Qualified Assets

Qualified assets are tax-advantaged accounts with contributions that are tax-deductible (e.g., Traditional IRAs and 401(k) plans) with distributions generally taxed upon withdrawal, or with contributions that are made on an after-tax basis but that grow tax-free (e.g., Roth IRAs and Roth 401(k) plans).

Notably, IRAs are typically referred to as "qualified" even though they are not always covered by ERISA and, therefore, not typically qualified in a technical sense. But, for the purposes of estate planning, pre-tax retirement accounts, whether they consist of a Traditional IRA or 401(k) plan, are generally approached with the same type of planning strategy.

Quasi-Qualified Assets

While not a technical term, "quasi-qualified assets" are assets that don't fit into either the "non-qualified" or "qualified" categories, but that need to be approached carefully because of their unique tax aspects.

For example, a non-qualified annuity may carry the same attributes as a retirement account when it comes to the withdrawal of income; however, a non-qualified annuity will not be afforded a basis adjustment at death, and the beneficiary will pay taxes on the deferred gains in the contract. Additionally, assets such as certain bonds or stocks that were previously subject to a Net Unrealized Appreciation (NUA) election may not receive a basis adjustment, and therefore may need to be approached from a planning perspective with the understanding that a beneficiary may incur some tax liability (for pre-death income activity) after inheritance.

Assessing The Different "Types" Of Beneficiaries And How Leaving Them Certain Asset Types Can Affect Them

Just as no 2 estates consist of the same assets, no 2 beneficiaries are the same. Even for siblings, the differences can be striking in many different areas. These differences can affect the way clients plan their estates, but most often, the planning that results from these differences relates to control. For example, one beneficiary who is a spendthrift may receive their inheritance in a discretionary trust managed by a third-party trustee, whereas a beneficiary with 'a good head on their shoulders' may receive their inheritance outright and free of trust. However, there are 2 particular aspects that are often overlooked in estate planning: 1) relative income levels and earning potential, and 2) state income tax levels for beneficiaries' states of residence.

Income levels and earning power can have a significant impact on the tax liability due upon receipt of an inheritance. For instance, if 2 siblings are viewed as trustworthy and fiscally responsible, the estate plan is likely to divide assets up equally without an eye toward tax efficiency despite the fact that they may have vastly different income earning levels. Certainly, a client could have multiple children who are all 'doing well' but are in very different income situations. This is not only in scenarios where one child is a doctor and another a schoolteacher, it could also be that the spouses of beneficiaries have vastly different earning power that affects their tax status.

Not only is income earning power not typically assessed, neither is state of residence. For instance, if one sibling lives in California and the other in Florida and they make the same amount of income annually, the relative income tax liabilities could have a difference of as much as 12.3% (since California's state income tax brackets range up to 12.3% and Florida has no state income tax)!

With such a disparity in the potential tax liabilities for certain beneficiaries inheriting certain asset types, the ultimate amount of post-tax wealth that is passed on to them can be vastly different depending on how the assets are apportioned to the beneficiaries. At the end of the day, clients are likely focused on tax efficiency and having the most amount of wealth in their family's hands while keeping the plan equitable. By leaving assets that are embedded with untaxed income to a beneficiary who will inevitably be subject to a substantial tax liability (Federal and/or state) when there are other beneficiaries with a far lower potential income tax rate, a significant portion of the estate may needlessly end up with the government post-inheritance.

It is also important to add another category of beneficiaries that is an aspect of many estate plans – charities. As tax-exempt entities, charities incur no income tax liability as the recipient of a previously tax-deferred asset. Therefore, when a charity is involved, it is important to consider how it will fit into the plan and which asset or assets the charitable bequest should come from.

How To Implement An Asset-By-Asset Estate Plan That Is Fair, Equitable, And Tax-Efficient

Before reviewing how an asset-by-asset approach can help the estate planning process in a fair, equitable, and tax-efficient way, it is helpful to first understand the importance of accounting for disparities in the income tax rates of the beneficiaries when planning a typical estate.

Consider the following example:

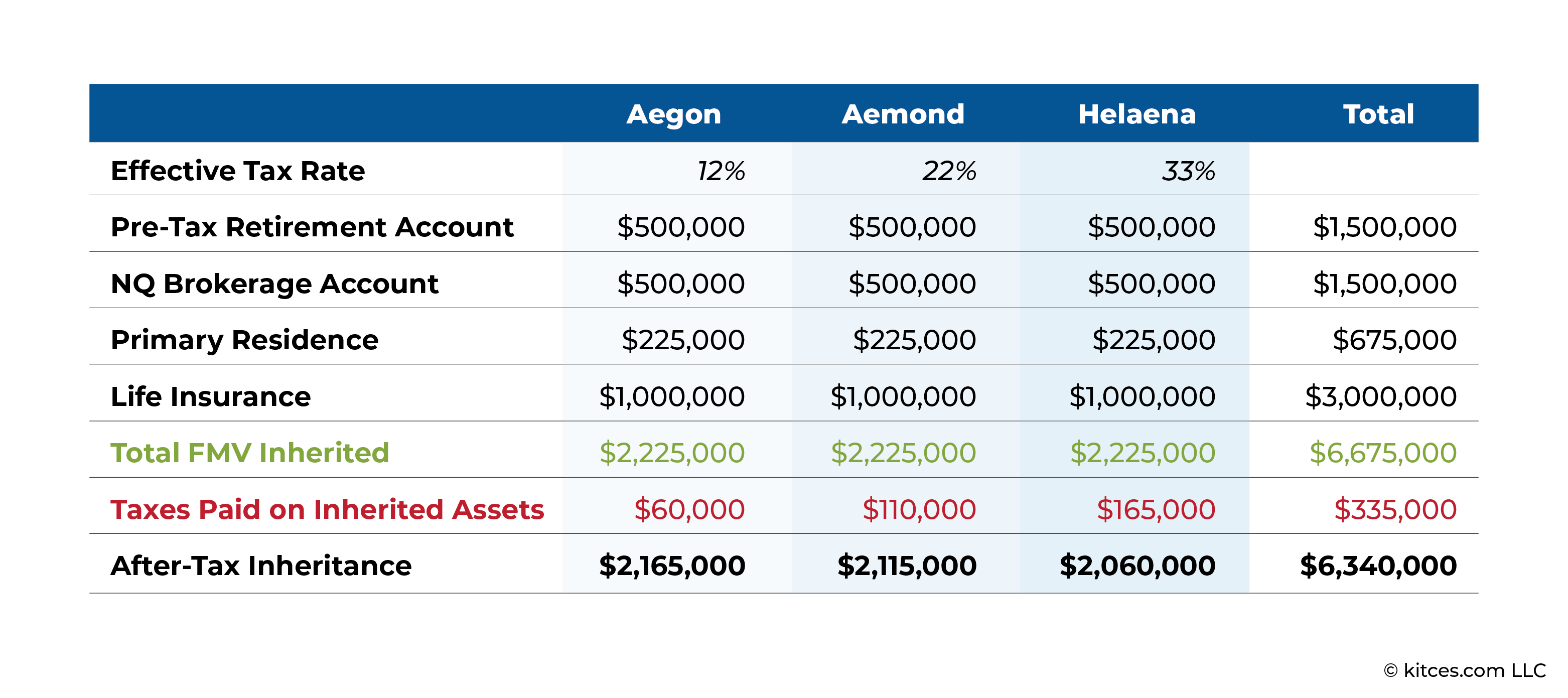

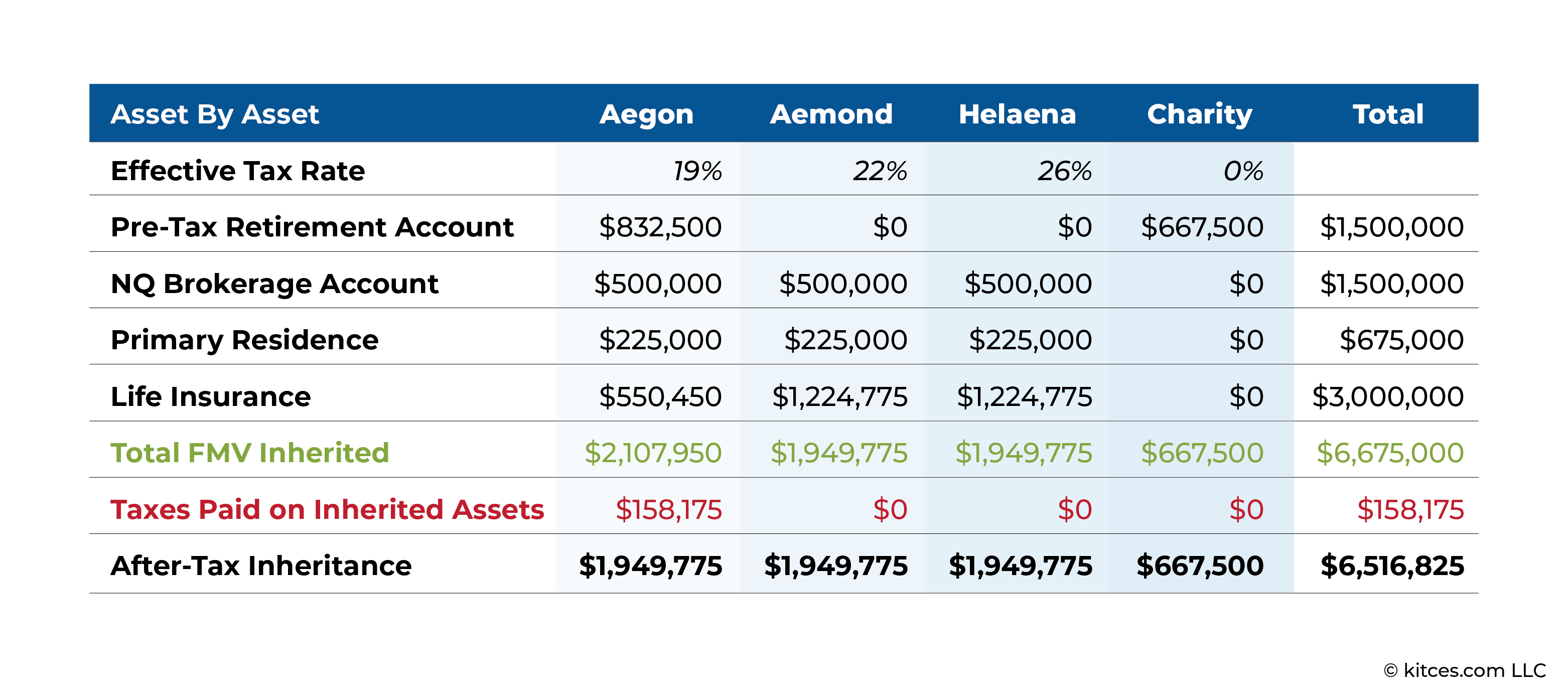

Example 1: Alicent is a client who has 3 children, Aegon, Aemond, and Helaena, and an estate valued at $6,675,0000 and wishes to divide the estate amongst the beneficiaries equally (1/3 each).

The estate consists of pre-tax assets totaling $1,500,000, non-qualified assets (subject to stepped-up basis) of $1,500,000, a primary residence with a fair market value of $675,000, and life insurance with a tax-free death benefit of $3,000,000.

Alicent's advisor learns the following about her children's income and tax rates: Helaena is a high-income earner in a state with a state income tax, Aemond is a moderate-income earner, and Aegon is a low-income earner in a state without a state income tax.

Taking into account each child's effective income tax rate and the respective assets they are set to inherit, the advisor determines how a 'one big pot' approach would turn out:

As each beneficiary will be inheriting an equal share of the pre-tax assets, they will each incur income taxes at their respective tax rates on withdrawal from the account (likely over a 10-year period under the SECURE Act rules).

This results in Helaena, the high-income earner, ultimately 'inheriting' the least amount from the estate due to her high income-tax rate. But, perhaps more importantly, this approach may have resulted in more money in the hands of the IRS from the estate than otherwise necessary if a comprehensive planning approach was taken, as the example in the next section will show.

With the common client goal of paying the least amount in taxes while treating the beneficiaries equitably, it would be prudent to see if a different approach could yield more advantageous results.

Consider this revised estate planning strategy:

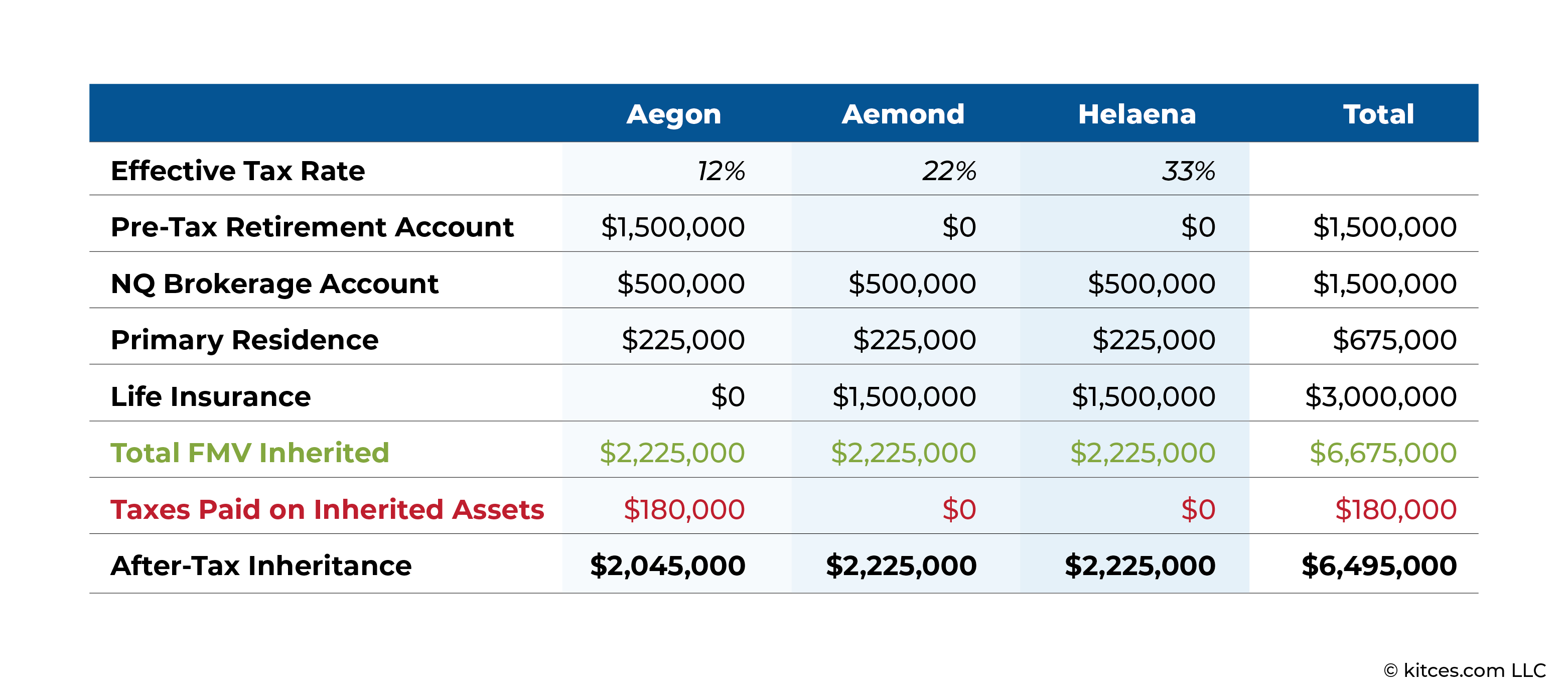

Example 2: Alicent, from Example 1, visits her financial advisor who is aware that her eldest 2 children, Aemond and Helaena, have a high effective aggregate Federal and state income tax rates compared to her youngest child Aegon. Thus, the advisor proposes that shifting a beneficial interest of the pre-tax retirement account to Aegon (in the lowest tax bracket) and splitting life insurance benefits between Aemond and Helaena could be more tax efficient.

The proposed division of assets would look like this:

By adjusting the allocation this way, the total tax liability has decreased, with the after-tax inheritance amount from the estate increasing by $6,495,000 – $6,340,000 = $155,000! That means that this strategy ultimately promotes more wealth to be passed to the beneficiaries by accounting for what will happen to the proceeds once in the hands of the beneficiaries.

Although the total amount of wealth retained by the beneficiaries in Example 2 was ultimately higher than the 'one big pot' approach in Example 1, The lowest-income child of the advisor's client was inequitably treated because they bore the brunt of taxation of the estate's assets.

The good thing is that shifting the allocation of inherited assets can provide a solution to that inequity; consider the revised strategy the advisor proposes in the example below:

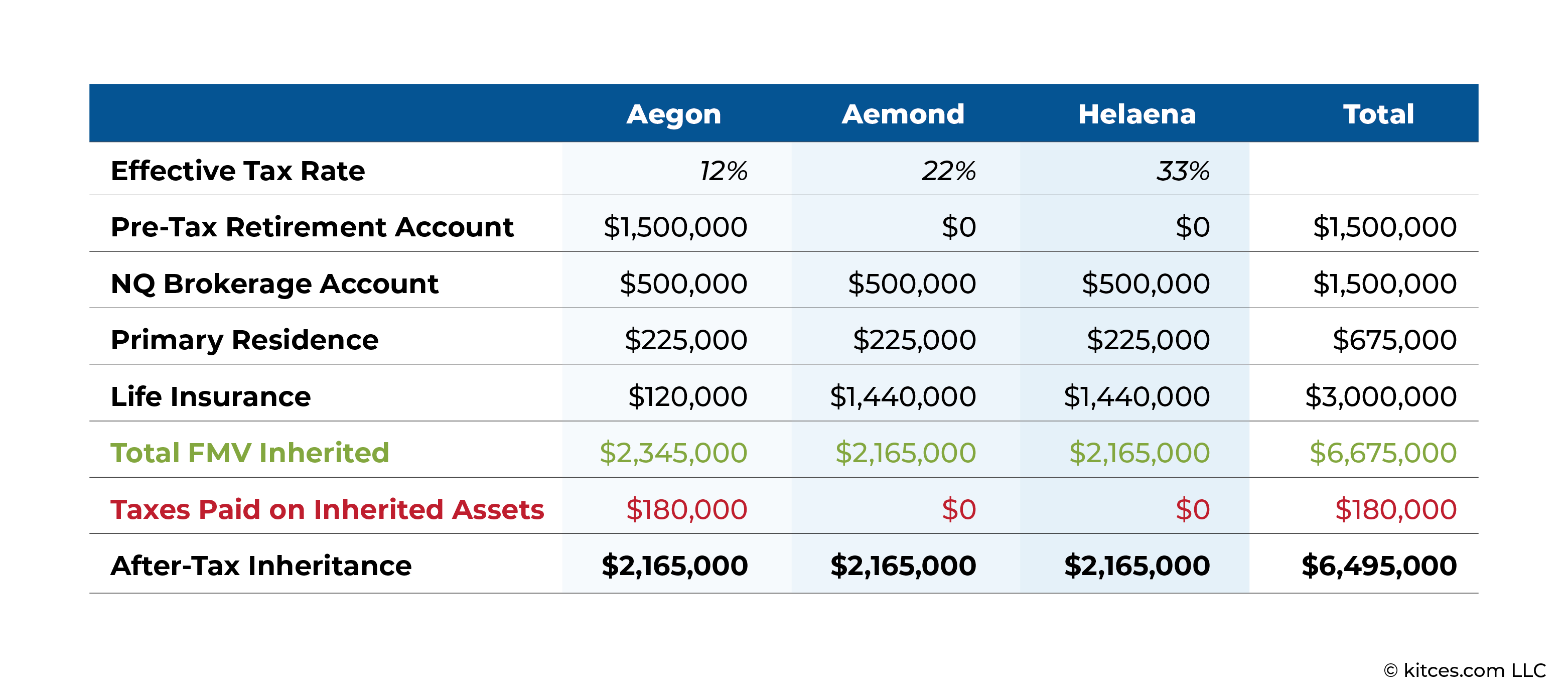

Example 3: Upon further review of his client Alicent's estate planning strategy, the advisor realizes that adjusting the pre-tax retirement account and life insurance assets as proposed in Example 2 would result in a lower net after-tax inheritance for her child Aegon. And because Alicent wishes that her children are equitably provided for, the advisor revisits the proposed strategy.

By reapportioning the life insurance assets with a small share allocated to Aegon and the remainder split between Aemond and Helaena, the advisor is able to propose a revised strategy that accounts for the disproportionate tax liability that would have been owed in Example 2:

Nerd Note:

Of course, these are simplified examples that do not take into account asset growth or the income taxes associated with the non-qualified investments over the pre-tax retirement distribution period. Additionally, understanding the tax situations of each beneficiary is important to recognize how allocating inherited assets may provide enough additional income to increase the beneficiaries' effective tax rates.

Notably, the estate was able to retain the same savings in Example 3 as in Example 2, but in a manner where, at the end of the day, all beneficiaries have been treated equally with respect to their after-tax inheritances. Of course, in formulating an asset-by-asset approach, there will always be a heavy element of projection, and the likelihood of things shaking out exactly equally is highly unlikely (to put it mildly).

Additionally, the benefits of this approach can either increase or decrease as various factors are assessed, including 1) the total estate value, 2) the weight of the estate toward pre-tax assets, and 3) the level of disparity in income-tax rates of the beneficiaries.

It may not always make the most sense to push all of the pre-tax assets to the beneficiary in the lowest income-tax bracket. For example, perhaps one beneficiary has an exorbitant state and Federal effective tax rate whereas the other 2 are in a similar tax situation. In this case, a more comprehensive analysis may be required, which might reveal whether It might be prudent to perhaps split the liability amongst the 2 lower earners (even if they aren't in exactly the same income-tax bracket).

The Role Of Charities As Estate Beneficiaries

As discussed earlier, charities are also an important part of many estate plans. When a charity is involved, it can be somewhat easy to plan for the overall amount retained by the beneficiaries to increase after taxes by leaving the tax-deferred assets to the charity first. This is because charities are tax-exempt and are typically selected to envelop as much of the tax liability as possible.

For example, if a charity is designated as a 10% beneficiary of an estate under a trust document, the client should instead consider whether the trust is the best place to make the bequest from, or whether the charity should be named as beneficiary of a specific asset (like a pre-tax retirement account).

Consider the following example:

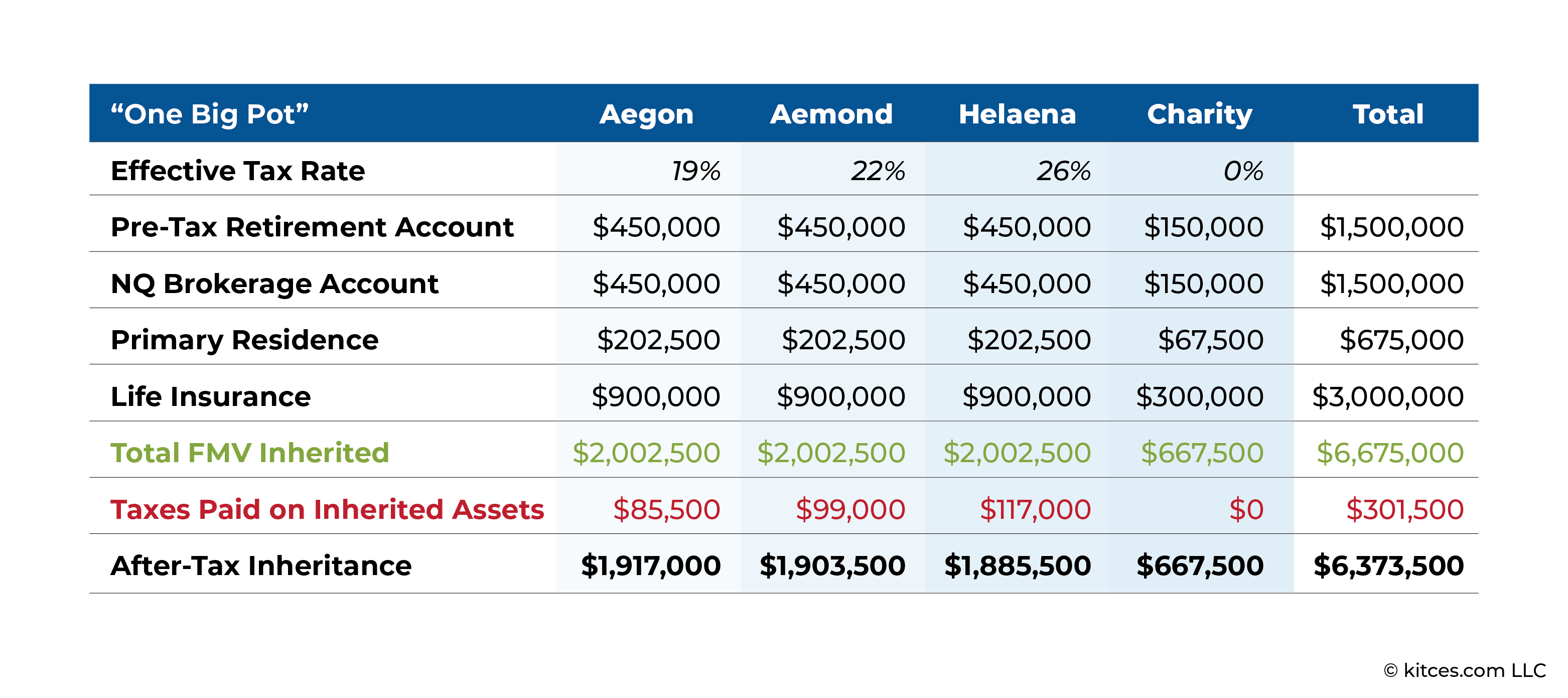

Example 4: Alicent, the client from previous examples with an estate valued at $6,675,000, now wants to consider leaving 10% of the estate to a charity. By taking a 'one big pot' approach, where the charity receives 10% of each asset in the estate, Alicent's advisor estimates the total taxes paid on the inherited assets would be $301,500, with an after-tax inheritance totaling $6,373,500.

However, Alicent's advisor points out that they could instead elect to have the charity receive $675,000 specifically from the pre-tax retirement account, with the remainder of the estate left to her individual beneficiaries.

The power of taking such an approach with a charity involved is shown in the table below. This asset-by-asset strategy results in less total tax compared to the 'one big pot' approach, with the after-tax inheritance for the beneficiaries increasing by $6,516,825 – $6,373,500 = $143,325!

Notably, naming a charity as a beneficiary of qualified accounts may be the easiest way to implement an asset-by-asset approach (without the detailed analysis and risk of inequity amongst the individual beneficiaries), because the charity's tax rate will inevitably always be 0%.

How Advisors Can Help Implement An Asset-By-Asset Estate Plan

One beauty of asset-by-asset planning is that it does not always need to impact the underlying estate plan documents, and the advisor can play an essential role in ensuring that the strategy is implemented as intended. As illustrated in Example 4 above, the savings from the asset-by-asset approach were achieved by re-allocating the beneficial interests under the retirement accounts and life insurance death benefit. These, of course, can be accomplished through updating beneficiary designations without the need for an amendment to a trust or will. While it is always essential to include the client's estate planning attorney in actions that affect the overall plan, by performing this type of analysis and helping the client execute it, the advisor has played a key role in unlocking – and providing – tremendous financial planning services and value.

Of course, assets are not always positioned in such a way that such changes can avoid affecting the existing estate plan documents. Therefore, careful planning may be required by an estate planning attorney within the trust or will documents themselves in order to make an effective asset-by-asset estate plan. This doesn't mean that the advisor is not an essential part of the process. As I discussed in a previous blog article, advisors stand in a unique position to know the client far more intimately than an estate planning attorney. Typically, an advisor has annual meetings with clients and knows about a client's family makeup and dynamics, including the relevant details relating to their beneficiaries' income situations. Armed with this information, a client's advisor can identify client profiles where an asset-by-asset approach to estate planning is warranted and help develop a plan to accomplish it.

In developing the asset-by-asset approach, the advisor will need information that is perhaps not otherwise collected in the normal course of a client relationship. Anecdotally, a lot of information to help justify an asset-by-asset approach can be attained through discussion (e.g., one child is a doctor living in California and the other is a schoolteacher in Florida). However, once it is determined that an asset-by-asset approach may be warranted, the advisor would then need to dig deeper and acquire potentially sensitive information to assist in calculating the best way to design the plan.

Notably, this could include reviewing the tax returns of the client's children. As the planning would ultimately be for their benefit, the children may be amenable to this request. However, such requests are unusual and can require sensitivity in assessing whether the client would be comfortable with the approach.

Discerning When An Asset-By-Asset Approach Is Warranted

Many times, trying to predict such factors as the future income of beneficiaries or the long-term performance of assets can be difficult. Therefore, an asset-by-asset plan could require more ongoing review and maintenance than a less complex estate plan without specific asset assignments by beneficiary. So the question will always be "Is it worth it?"

The reality is that the effective tax rates of a client's beneficiaries will inevitably change, and an asset-by-asset plan based on the beneficiaries' tax circumstances at the time the plan is created can be dramatically different when the beneficiaries inherit the estate. And if there is little, if any, certainty that the beneficiaries' effective tax rates will be significantly different in the future, an asset-by-asset planning approach may yield little benefit.

Consider another example.

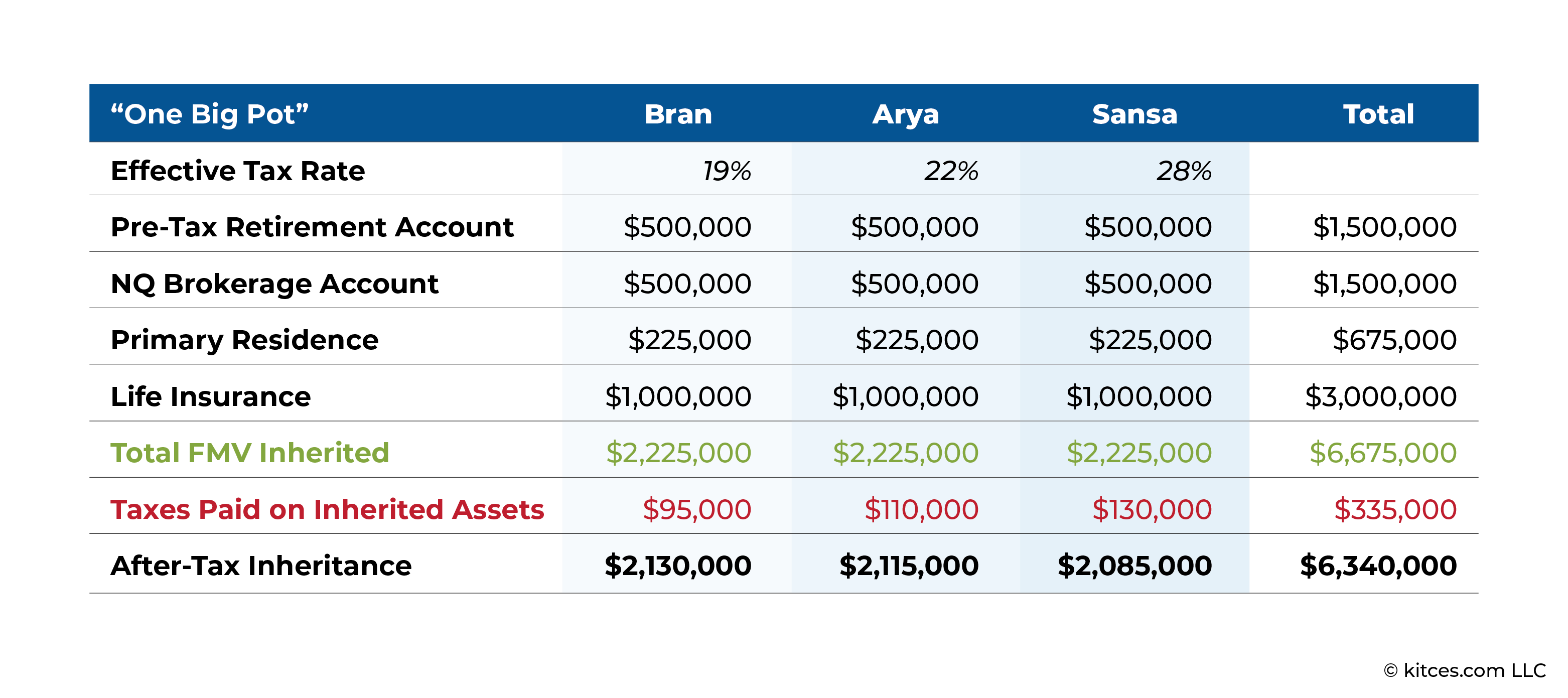

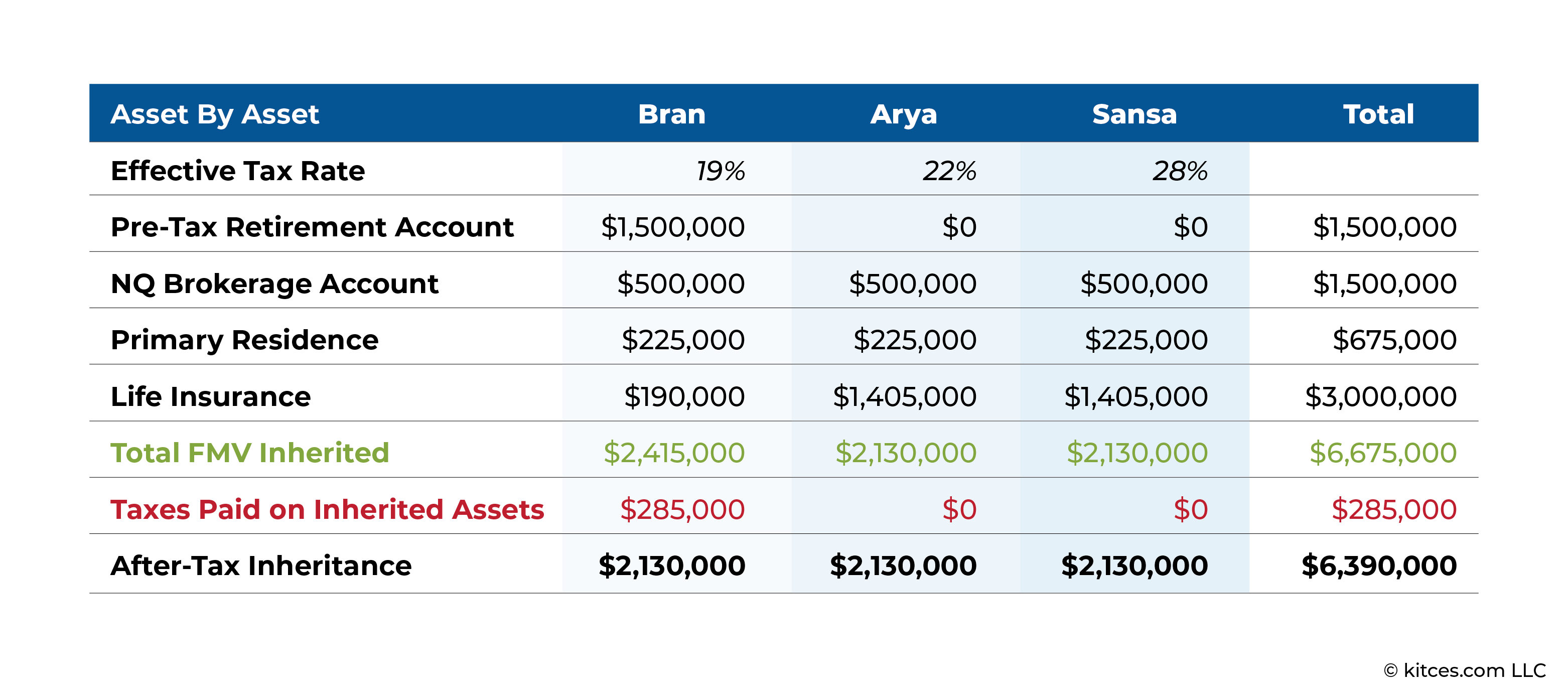

Example 5: Ned is another client with a total estate, identical to Alicent from prior examples ($6,675,000 consisting of pre-tax retirement account, a non-qualified brokerage account, primary residence, and a life insurance policy). Ned also has 3 children, but the effective tax-rate spread for Ned's children is much closer than Alicent's, where Ned's kids have effective tax rates of 19%, 22%, and 28%.

Since Ned's advisor identified that the asset-by-asset approach resulted in significant tax savings (and thus a higher inheritance for Alicent's kids), he revisits the asset-by-asset approach for Ned. The simplest 'one big pot' approach for Ned's estate plan would yield a total after-tax inheritance of $6,340,000, as follows:

However, when assessing the asset-by-asset planning strategy, the advisor discovers that the increase in total after-tax inheritance, while not necessarily insignificant, is only $6,390,000 – $6,340,000 = $50,000; much smaller than the $143,625 net increase for Alicent's beneficiaries (who had a much higher disparity in effective tax rates).

In Example 5 above, the ultimate after-tax savings to the estate, $50,000, is a sizable savings. However, as the tax rates of Ned's beneficiaries are much closer in this example, compared to Alicent's beneficiaries in Example 4 inheriting an equivalent estate (where the asset-by-asset approach netted an after-tax increase of $143,325), they raise a lot of questions as far as the predictability of future tax rates and whether the disparity would hold when the plan actually comes into action (at death). This may be a scenario where 'the juice is not worth the squeeze' and, taking into account the circumstances of the beneficiaries, leaving each asset to the beneficiaries in equal shares may be warranted.

Accordingly, it's important to discern when an asset-by-asset approach is truly warranted (e.g., when it seems likely that income and tax rate disparities will remain relatively steady among beneficiaries) to avoid spending time and resources managing a plan that maintains how assets should be designated to ensure that each beneficiary receives an equitably balanced inheritance, when using the 'one big pot' approach is likely to yield an inheritance distribution that would ultimately be no different (or not much better) than the asset-by-asset plan.

As discussed earlier, the result of an asset-by-asset approach will never work out exactly as intended; it can just increase the likelihood of equity and more dollars remaining within the family after all pre-death accumulated income items have been taken.

Additionally, this type of planning could require far more maintenance than a typical estate plan. A factor that could impact this approach is the client’s lifetime financial plan, including withdrawals of assets or changes in asset location. For instance, if a client performs Roth conversions or draws down their qualified accounts, then it could significantly impact the efficacy of the asset-by-asset plan because the tax status of the assets and/or their proportional balances compared to assets with different tax attributes have changed. Beneficiaries may also change their states of residence, get married, get divorced, change careers, and experience other life events that would greatly affect the efficacy of an asset-by-asset estate plan.

So this means that helping clients implement an asset-by-asset planning strategy requires periodic check-ins, which are critical to help the advisor determine if life has changed not just for the client but also for their children.

Therefore, while the savings associated with this type of planning can be substantial, the circumstances that could fundamentally alter the approach are aplenty. Which suggests that this type of approach is generally more beneficial (and more likely to be worthwhile to implement) when there is both a potential for substantial savings and also when the beneficiaries' income status and income tax disparities are not likely to change substantially over time.

Because every client is different, they will always have uniquely different estate planning needs, priorities, goals, and opinions about their beneficiary's level of fiscal responsibility. This, of course, impacts the approach to planning for the clients themselves and potentially how they leave assets to beneficiaries. However, another important yet often overlooked consideration includes what happens to the assets from an income tax perspective after the assets reach their intended destination.

Taking a more holistic approach by viewing each asset within a client's estate independently can help advisors assess how heavily beneficiaries will be taxed when they inherit the assets. And by expanding that view to determine whether there is a way to pass more of the estate beneficiaries after all pre-death income has been taxed, advisors can potentially offer their clients a more equitable distribution plan for their beneficiaries, passing the most amount of wealth possible to the next generation!