Executive Summary

Donor-advised funds (DAFs) are flexible tools which can be used for a number of charitable giving purposes. One increasingly popular use is to use an "endowment-style" DAF in lieu of a private foundation for those with charitable intentions of leaving a legacy that will continue to have an impact on the world many years into the future, given that DAFs are cheaper to operate, more tax efficient, more flexible, and eligible for higher limits on tax deductibility of contributions. However, while much attention has been given to how individuals should allocate a portfolio throughout their own lifespan, considerably less attention has been given to the question of how to best allocate a portfolio if one's time horizon is "forever". Especially when it has flexibility with respect to its distributions.

In this guest post, Dr. Derek Tharp – a Kitces.com Researcher, and a recent Ph.D. graduate from the financial planning program at Kansas State University – analyzes considerations when coordinating investment and spending policies of an endowment-style DAF, finding that for donors who have the willingness and ability to be flexible in their distribution policy, investment allocations can be much more aggressive than those commonly adopted by endowments, generating far more income for charitable beneficiaries and build a larger endowment value to sustain giving well into the future.

The traditional approach to investment an endowment is still a well-diversified conservative or moderate growth portfolio - e.g., a 60/40 portfolio - owing in large part to the fact that most endowments have a high need for distribution stability (e.g., university endowment funds that need to fund ongoing operating costs that universities have become highly dependent on). However, in the context of an endowment-style DAF, the reality is that individual donors often have far more flexibility about when and how much they donate. Which is important, especially with the possibility of 100+ year time horizons that allow for immense (and intuitively-difficult-to-grasp) compounding.

In fact, a Monte Carlo analysis (based on historical market returns) of an ultra-long-term endowment-style DAF with a flexible (e.g., percentage-of-assets) distribution policy finds that shifting a fairly modest $100k endowment-style DAF from a balanced portfolio allocation (50/50) to an aggressive allocation (100/0) would result in an extra $13.6 million in inflation-adjusted median endowment account value after 100 years, while also generating an additional $5.6 million in distributions to charitable institutions along the way (albeit with some volatility in annual distributions from year to year)! Further, adopting a simple dynamic spending/distribution strategy (e.g., forego a distribution in years with less than a 2.5% real return), results in an additional $6.1 million boost in real residual value and $1.2 million more in cumulative charitable distributions (as distributions are skipped in some years but made up over time)!

Ultimately, the key point is to acknowledge that willingness to accept some spending instability, coupled with ultra-long-term time horizons to compound, makes it feasible to have a far more aggressive portfolio that still result in substantially more assets going to the charitable institutions that donors care about. Of course, donors must be willing to stay the course, avoid projecting their personal risk tolerance onto the endowment, and be comfortable adopting an allocation that is much more aggressive than the "norm" among prominent endowments... but donors should be cognizant of the tremendous potential of investing more aggressively (and the impact of long-term compounding) if they are willing and able to be flexible!

Donor Advised Funds as Tools for Charitable Giving

Donor-advised funds (DAFs) are tools which can be used for a variety of charitable giving purposes. The primary benefit of a DAF is that it allows individuals to (irrevocably) donate assets to a charitable entity today (allowing that individual to receive a tax deduction now), while delaying the ultimate distribution of the assets to a final charitable entity in the future. In essence, the DAF functions as a conduit, and in the process provides greater flexibility in the timing of charitable gifts, allowing donors to effectively “front load” charitable contributions (e.g., into a high-income year), yet retain flexibility in deciding when and how much will be given to the final charitable recipients in the future.

In addition to allowing donors to “lump” charitable giving into a single year (which is potentially of increased interest after the TCJA of 2017), donor-advised funds have the benefit of growing tax-free into the future. Since technically a DAF is managed by a charitable entity itself (e.g., a community foundation or a non-profit entity with a close tie to a for-profit firm, such as Vanguard Charitable, Fidelity Charitable, or Schwab Charitable), the DAF receives the same favorable tax treatment as other investments held by a charitable entity.

The main difference is that with a charity itself, once the funds are donated, they are in control of the charity. In the case of a DAF, as the “donor-advised” name implies, the entities which manage DAFs typically make a commitment to allow the donor to “advise” on the investments (either from a menu of options, more directly specifying the investments, or even appointing a financial advisor to manage the investments), as well as identify and “advise” on what qualified 501(c)(3) charitable institutions the DAF will send the money to at some point in the future. Notably, this isn’t a guarantee that the funds will be invested and donated exactly according to a donor’s advisement and wishes, but in practice charities which don’t keep their commitments to donors will struggle to attract other donors in the future (and so most will faithfully follow what its donors advise).

Giving in Perpetuity: Using An Endowment-Style DAF In Lieu Of A Private Foundation

One unique aspect of DAFs is that they can be used for a variety of different giving strategies. This flexibility allows for distribution strategies which range from giving away the entire DAF balance within the year of a gift (e.g., for administrative purposes, it may be much easier to donate highly appreciated and closely held stock to a single DAF which can then sell the stock and distribute assets to many different non-profits), or using the DAF to hold and invest a long-term base of charitable assets from which gifts will be made “perpetually” into the future.

In other words, DAFs can function in a manner similar to private (non-operating, grant-making) foundations… except that DAFs are also cheaper to operate, more tax efficient (by avoiding potential excise tax on investment income), more flexible, and eligible for higher limits on tax deductibility of contributions (treated as a public instead of a private charitable entity for the purposes of the annual limitations on charitable deductions).

As a result, DAFs are an increasingly popular alternative to private foundations, with the latter only used now for cases where there is a desire to engage in certain behaviors exclusive to private foundations (i.e., not allowed of DAFs), such as making grants to individuals, retaining even greater control over investments and assets, or compensating family members for involvement with a foundation.

Additionally, some states have even set up tax credits which reward donors for setting up DAFs designed to exist in perpetuity. As such, donors may be increasingly interested in setting up “endowment-style” DAFs which are established with the intent of existing in perpetuity. But this creates an interesting question for donors: How exactly should an account be allocated if the investment time horizon is “forever”?

How Endowments Invest Their Accounts

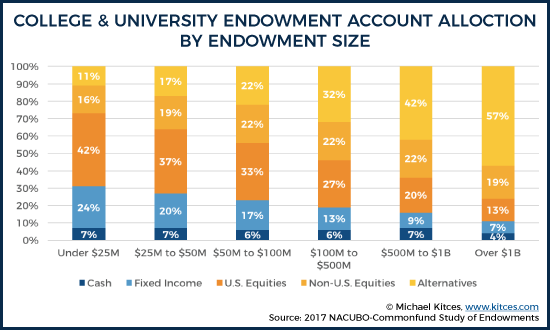

A natural response to the question “how should an endowment-style DAF be invested” is to look at the endowment accounts of non-profit institutions currently in existence and mimic their allocations. For instance, the 2017 NACUBO-Commonfund Study of Endowments (NCSE), provides a nice summary of how data gathered from 809 U.S. colleges and universities suggests that endowments invest their assets.

In general, the larger the endowment, the more assets they hold in alternative assets. Theoretically, this makes sense, since the long-time horizons and large asset values of (some) endowments allow them to better manage investment costs, liquidity constraints, and other limitations that can make alternative assets feasible for them (even if they remain impractical for many ordinary investors). On the other hand, smaller endowments that lack the economies of scale to conduct the due diligence needed for efficiently allocating as much assets towards alternatives, instead end up roughly approximating a 60/30/10 (stocks/bonds/alternatives) allocation.

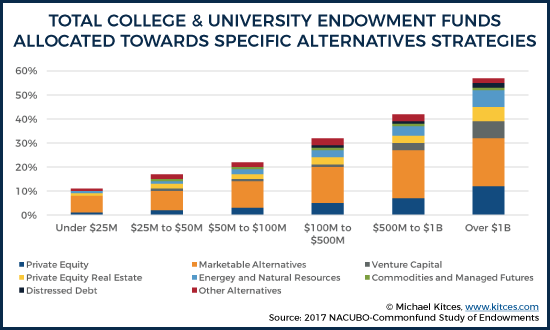

Of course, many different “alternative” strategies exist, from those that may take comparable or even larger risks than traditional equity strategies (e.g., venture capital), to those which take comparable or even lower risks than traditional fixed income strategies (e.g., low-volatility hedge funds). To get a better understanding of the risk profile within endowment funds, the 2017 NACUBO-Commonfund Study of Endowments breaks out how the colleges and universities analyzed are investing their alternative allocations.

As you can see in the chart above, at all endowment levels, the bulk of alternative assets are invested in “marketable alternatives” (which includes hedge funds, absolute return funds, market neutral funds, long/short strategies, and others), so it’s hard to say precisely how much risk endowments are taking through their alternatives allocation, but in looking at the smallest endowment accounts (which would likely be closest in make-up to the asset levels donors would put in an endowment style DAF), we might approximate that small college and university endowments invest in portfolios with roughly the risk profile of a 60/40 to 70/30 traditional stock and bond allocation.

So does that mean that mean that the typical endowment-style DAF should be allocated similarly? Unfortunately, no, it’s not that simple.

Different Goals for Different Endowments Based On Distribution Needs

At first glance, it may seem to make sense to turn to colleges and universities for guidance on how to manage an endowment-style DAF, but the reality is that not all endowments have the same goals. In particular, endowments may vary in their willingness to adjust distributions based on market conditions.

Consider a typical university endowment. Universities are often dependent on their endowment to fund scholarships to students, pay faculty salaries, support research, and provide services to their local communities. Because endowments at many universities are very large—Harvard, Yale, Stanford, and Princeton all have over $20 billion in assets, while over 100 other universities have endowments larger than $1 billion—many universities have become reliant on the funds provided by their endowments for ongoing operations.

However, a donor with an endowment-style DAF is likely not in a similar position. Even if a donor’s ultimate goal is to give a fairly consistent amount from year to year, the institutions that an individual gives to are unlikely to be as dependent on that individual for their funding. In other words, while a certain State University may be dependent upon their endowment to fund ongoing operations, that State University is likely not dependent on John Smith’s donation (from his donor-advised fund) in any given year. As a result, individuals establishing endowment-style DAFs may want to consider the long-term outcome of adopting various types of spending policies.

Endowment Distribution Policies

Historically, institutional endowments were generally assumed to have an obligation to protect the principal of their endowment, taking an “income only” approach to distributions. Income was generally understood to include funds from sources such as interest and dividends, but did not include capital appreciation. As a result, endowments were incentivized to invest in income-generating assets such as bond and mortgages. However, as it became clear that this preference for income-generating assets over assets with more potential for capital growth did not necessarily serve the interests of donors, the institutions which rely on endowment funding, or society more generally, reforms were proposed to allow endowments to adopt more of a modern total-returns investment approach.

In 1972 the National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws (NCCUSL) drafted the Uniform Management of Institutional Funds Act (UMIFA), which allowed institutions to spend both income and capital appreciation. However, endowments were still limited by UMIFA’s historic dollar value rule, which generally required that appreciation could not be spent if the fund value did not exceed the original value of gifts to the fund (i.e., the fund’s “historic dollar value”), leading to spending constraints if a market correction led to an endowment being “underwater”—again unintentionally pushing institutions towards the use of income-generating assets. As a result, in 2006, the NCCUSL drafted the Uniform Prudent Management of Institutional Funds Act (UPMIFA), which further increased spending flexibility for endowments by eliminating the need to distinguish between income and principal—officially permitting the spending of principal, so long as the endowment is managed in a manner that “prudently” protects the purchasing power of the endowment.

Without the restrictions that were historically in place, endowments now have much greater flexibility in crafting a distribution policy which best aligns with that endowments purpose.

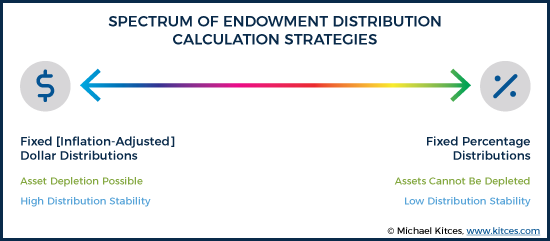

As a result, in today’s world, a well-managed endowment has not only an Investment Policy Statement but also a Spending or Distribution Policy Statement. Similar to withdrawal policies in retirement, endowment style annual distribution policies can be thought of at two extremes: fixed-dollar spending strategies, and fixed-percentage spending strategies.

A fixed-dollar distribution policy would mean that an endowment targets some specific level of distributions, and then adjust those distributions annually for inflation (e.g., a $2.5M endowment-style DAF may want to donate an initial $100k per year, and then adjust that amount annually according to CPI). This is closest to the distribution pattern commonly assumed of retirees (i.e., a “safe withdrawal rate” approach), at least in terms of non-discretionary expenses that a retiree needs to have in order to ensure they will not run out of money. Of course, with such an approach it’s important to set an initial spending rate that is “low enough” to survive the risk of an unfavorable early sequence of returns.

At the other end of the spectrum is a fixed-percentage strategy. Under such a strategy, an endowment may target distributing some fixed percentage (e.g., 4%-5%) of endowment assets annually. Unlike fixed-dollar distributions, which can run out of money if real returns are not sufficient to continually preserve (or recover losses on) the principal, fixed-percentage strategies will never entirely spend down their assets (as when the withdrawal is a percentage of the portfolio itself, if the portfolio declines, the withdrawals are reduced accordingly, although with ‘catastrophic’ losses the remaining distributions may potentially be minuscule).

In practice, endowments tend to take more of a fixed-percentage approach, however, some greater spending stability is often built in by distributing some fixed-percentage (often 4%-5%) of a moving average endowment value (e.g., 5% of three-year average portfolio balance). By smoothing out the portfolio value, endowments can maintain greater stability due to experiencing less distribution volatility driven by market gyrations, although this increased stability can also mean a greater risk of actually running out of assets.

Additionally, a Vanguard report notes that other distribution strategies common among endowments are percentage-based distributions with a ceiling and floor tied to the initial distribution amount (e.g., 5% of three-year average portfolio balance, not to be less than 80% of the real initial distribution or exceed 120% of the real initial distribution) and “hybrid” approaches which contain elements of both fixed-percentage and fixed-dollar distributions (e.g., annual distribution comprised of two parts: (1) 2% of three-year average portfolio balance, and (2) a fixed-dollar distribution based on 2% of the initial endowment value adjusted annually for inflation).

Spending Policies Influence Investment Policies

Understanding an endowment’s spending policy matters, because just as fixed versus variable retirement spending policies influence sustainable distribution rates and which investment allocations are appropriate for a retiree, the spending policy of an endowment influences the investment allocations which are suitable for an endowment.

All else being equal, the more flexible and endowment’s spending policy is, the more aggressively an endowment can afford to invest, given the ability to defer distributions and wait out a stock market decline. In fact, given that endowments have a perpetual time horizon, and potential to adopt more flexible spending policies than any retiree, arguably the upper limit for how much risk endowments can prudently take is far higher than any comparable limit for a retiree (or prospective retiree).

For instance, an endowment donor who wishes to maximize total giving and is not concerned about distribution consistency from year-to-year may seriously consider 100% equity allocations (or even leveraged strategies) to fulfill their unique charitable goals. By contrast, a donor who wishes to maintain consistent giving year-to-year (like a university) may need to take a more balanced approach.

DAF Spending Flexibility And Long-Term Endowment-Style Asset Allocation

In order to assess the long-term implications that spending and investment policies have on an endowment’s ability to grow and give, we can simulate (with Monte Carlo projections) the potential trade-offs.

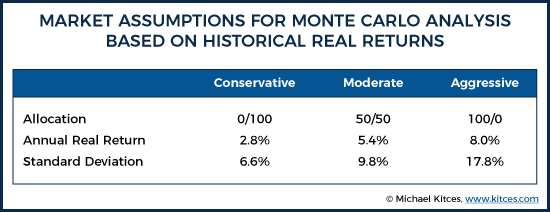

Specifically, we evaluate below both fixed-dollar and fixed-percentage distribution strategies with three portfolio allocations: (1) conservative (0% stocks and 100% bonds), (2) balanced (50% stocks and 50% bonds rebalanced annually), and (3) aggressive (100% stocks and 0% bonds).

(Note: The real return assumptions below are based on Robert Shiller’s annual return data set going back to 1871 on stocks [S&P 500], bonds [One-Year U.S. Treasury Bills], and inflation [U.S. Consumer Price Index]. Notably, because Monte Carlo naturally incorporates volatility drag into projections, real returns are based on arithmetic rather than geometric real returns.)

Fixed-Dollar Distribution Strategies

In order to examine the impact of long-term investment allocation decisions when utilizing a fixed-dollar strategy, an initial endowment value of $100,000 was assumed. In each case, a distribution based on this fixed dollar value was determined (e.g., $5,000) and then adjusted annually for inflation.

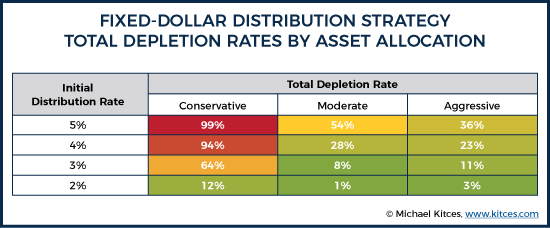

Regarding the impact of asset allocation on total endowment depletion, the results largely indicate what we might intuitively expect. For instance, with a conservative allocation (average real return of 2.8%), fixed-dollar distribution rates initially beginning at rates of 3% and above are problematic. 64%, 94%, and 99% of the time the endowment was depleted based on initial distribution rates of 3%, 4%, and 5%, respectively. However, at a 2% distribution rate, the endowment only ran out of money 12% of the time, therefore being able to generate $200,000 in real charitable gifts (2% of $100,000 each year for 100 years) with a median residual value of $336,000.

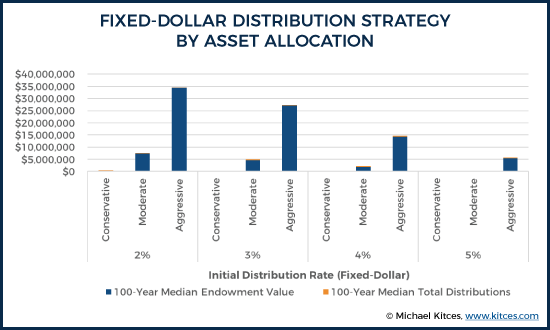

It's important to bear in mind that because fixed-dollar strategies do not vary in the amount distributed from year-to-year, as more aggressive portfolios (with higher assumed real rates of return) are analyzed, distributions still never exceed the maximum amount of distributions possible (initial real distribution * 100 years), regardless of how large the endowment grows. Therefore, while a 2% initial distribution rate generates $200,000 in real distributions regardless of the allocation, the only difference is that the median endowment values increase to $7.4 million with a balanced allocation and $34.3 million with an aggressive allocation. In other words, with a fixed-dollar withdrawal strategy, more aggressive portfolios “just” result in (much) higher remaining balances left over at the end.

Also aligned with intuition is the fact that at the highest initial distribution rates (e.g., 5%), an all equity portfolio reduces the probability of depletion relative to a balanced portfolio (because the higher returns are necessary to sustain), but at initial distribution rates of 3% or lower, the stability provided by a balanced allocation reduces the probability of depletion relative to an aggressive allocation (as the higher risk/return profile isn’t needed to sustain the distributions, and just increases the risk of a bad sequence). However, with increased certainty still comes considerably lower median ending endowment values, as indicated above.

Notably, these differences are in real dollars, so if we assume an average annual inflation rate of 2.5%, a $1 million dollar difference indicated in the chart above would actually correspond to a roughly $12 million dollar (inflation-adjusted) difference 100 years from now. And it is this consideration which is probably the least intuitive for financial advisors. The magnitude of the impact of a long-term asset allocation decision is huge, and it is hard for us to intuitively grasp how large this impact would be compounded out over 100-year time horizons (or longer, since endowments exist in perpetuity), since we are far more used to thinking about time horizons of 30-60 years!

We can also use the results above to see why the “4% rule” would not apply in an endowment context. Recall that Bengen’s 4% rule applies to a 30-year time horizon. As Bengen also found in his well-known study, the safe withdrawal rate declined to 3.5% over a 45-year time horizon. Effectively, what the results here are suggesting is that for balanced and aggressive portfolios, a reasonably safe withdrawal rate over 100+ year time frames may be somewhere in the 2-3% range.

Fixed-Percentage Distribution Strategies

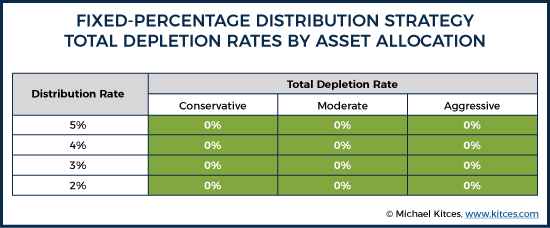

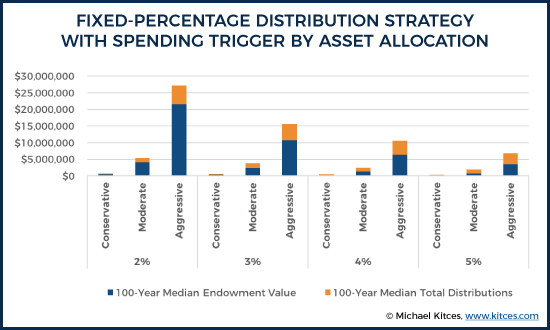

In order to analyze fixed-percentage distribution strategies, it was assumed that an initial endowment of $100,000 was used to support a distribution of a fixed percentage of the portfolio from the previous year (e.g., 5%). Notably, no smoothing (e.g., 5% of prior 3-year portfolio balance) was assumed in this analysis (despite the fact that smoothing is common in practice), in an effort to try and compare the most flexible annual distribution extreme (as smoothing would result in somewhat less response to market volatility, and therefore could result in portfolio depletion rates greater than 0%).

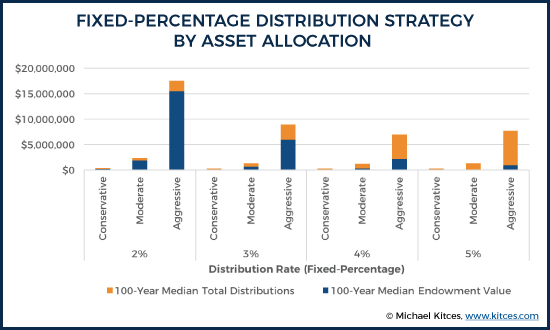

The relative strength of fixed-percentage distributions strategies becomes evident when looking at the results. Any allocation is now protected against depletion of the entire endowment, although it is possible that purchasing power of the endowment can be reduced in real terms (which may therefore mean that some combinations of fixed-percentage distribution rates and asset allocations can be seen as imprudent). For instance, despite the fact that a conservative allocation has a 0% depletion rate under all scenarios, the median endowment value is actually declining within the 3% - 5% distribution scenarios. In other words, although the portfolio is not running out of money, the purchasing power of the endowment is being eroded with time.

A fixed-percentage approach also helps guard against “excessive accumulation” within an endowment (relative to a fixed-dollar approach), as distributions are automatically increased under good sequence-of-return scenarios. For instance, at the 75th percentile, assuming a 2% initial fixed-dollar distribution with an aggressive allocation, only $200,000 in real dollars were distributed, whereas nearly $127 million in endowment value accumulated! By contrast, under a 2% fixed-percentage distribution with an aggressive allocation, over $18 million was distributed, while nearly $50 million was accumulated at the 75th percentile simulation.

Of course, this balance may still not reflect what any particular donor would prefer. A 4% fixed-percentage distribution more evenly balanced out distributions and endowment value over a 100-year time horizon ($7.5 million and $7 million at the 75th percentile, respectively). But the key point is that fixed-percentage strategies are inherently responsive to market fluctuations, whereas fixed-dollar strategies are not.

Fixed-Percentage Distribution with Minimum Return Distribution Trigger

Notably, how a distribution is calculated represents only one of the dimensions on which an endowment could decide to implement a flexible distribution policy. Another consideration would be adjusting (or even eliminating) annual distributions based on market performance itself.

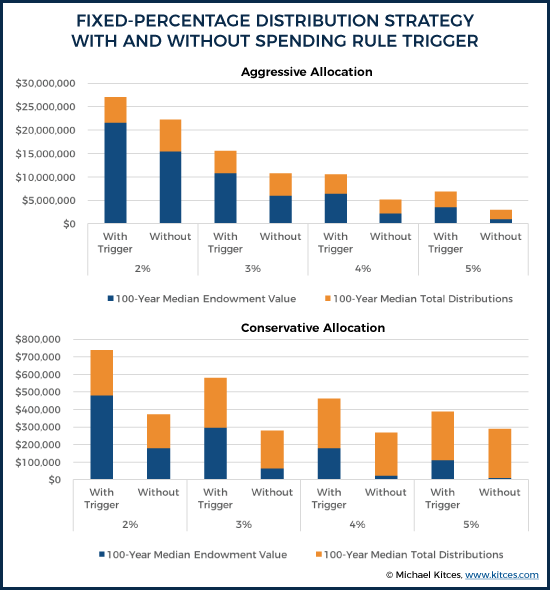

In order to examine how such a strategy could influence both endowment values and total distributions, a simple decision rule of “only distribute if real returns exceed 2.5%” was considered. In other words, a normal percentage-based distribution would be made only in the event that real returns were higher than 2.5% in a given year.

As the results above indicate, implementing a simple decision rule can have a positive impact on both preserving endowment value and increasing total giving. Of course, this works because an endowment cannot distribute anything if it runs out money. Therefore, preserving the endowment value also preserves the future cash flow that can be generated from the endowment. In other words, for an entity with a perpetual lifetime, skipping untimely distributions can not only preserve the endowment value, but can make-up for the missed distribution in the form of higher future distributions from a higher asset base.

For instance, when utilizing a conservative investment allocation, taking a fixed-percentage distribution regardless of actual returns in a given year eroded the endowment value when the distribution rate was 3% or greater (median 100-year values of $8,000 [5% distribution] to $64,000 [3% distribution]) while generating median distributions ranging from $193,000 (5% distribution) to $245,000 (3% distribution). By contrast, implementing a distribution trigger based on a 2.5% minimum real return preserved median 100-year endowment values ($111,000 at 5% distribution; $296,000 at 3% distribution) while also generating median distributions ranging from $277,000 (5% distribution) to $285,000 (3% distribution).

Notably, not all scenarios saw an increase in total distributions based on this particular trigger. When analyzing an aggressive portfolio allocation, 100-year median distributions were reduced from $6.8 million without the trigger to $5.5 million with the trigger, although median endowment value was also increased from $15.5 million to $21.6 million, resulting in an increase in real asset values that still exceeds the decrease in distributions (i.e., the distribution gap could be closed with a one-time distribution and still have a larger endowment balance going forward). Additionally, the trigger was still successful in increasing both median 100-year endowment values and distribution rates when utilizing higher distribution rates (e.g., 5%) with an aggressive allocation, resulting in a median endowment value of $3.5 million and median total distributions of $3.4 million when using the trigger, versus $900,000 and $2.1 million, respectively, without the trigger.

The Opportunity Cost of a Conservative Endowment Allocation

As the results from all of the various endowment strategies analyzed indicate, there’s a considerable cost to being overly conservative when selecting an endowment allocation. A more conservative allocation can certainly make sense when cash flow consistency is a primary motivation, as is common for “traditional” endowments (though even then, a more balanced approach will likely provide adequate stability with more long-term distributions and more long-term accumulation).

However, with a donor-advised fund—and to the extent that no particular institution is dependent on the cash flow from a given endowment—there’s a huge opportunity cost to not implementing a spending policy which incorporates fluctuations in the market, and takes advantage of flexibility in deciding when to make distributions… and then invests more aggressively, in a manner that is feasible once such spending flexibility is introduced.

Of course, institutional endowments could adopt the same course of action—particularly if they’re able to be more flexible with their spending. But in practice, it may still be difficult to do so, both because prospective donors may feel that funds are being poorly managed due to merely seeing the paper losses that inevitably occur with any aggressively allocated portfolio (and the loss of future contributions could result in an endowment ending up worse off), and also because endowments managed by committees of volunteers at small non-profits often have a high level of volunteer turnover (who may be less sophisticated and may inappropriately use their own personal risk tolerance to assess how much risk an endowment should take, and/or abandon an aggressive strategy at the worst possible time). And of course, there’s simply the fact that aggressively allocated endowments are not the norm (and there’s comfort in the “herd mentality” of looking to institutions like universities to guide the way), which could leave endowment committee members (or the fiduciaries they hire to take on investment responsibility) potentially subject to (baseless) allegations that a long-term aggressive endowment allocation is imprudent.

Nonetheless, in the context of individuals setting up their own endowment-style DAFs in particular, many of these obstacles can be avoided. And ultimately, the key point is to acknowledge that how an endowment-style DAF should be allocated depends on how flexible a donor can be and wants to be in distributing assets. Through the use of a quality spending and investment policy statement—which appropriately reflect the reciprocal influence each has on the other, while also managing behavioral risks by not allowing personal risk tolerances to influence an endowment’s investment allocation—donors can have a tremendous financial impact both now, and in the future, through the use of an endowment-style DAF!

So what do you think? How would you allocate an endowment-style DAF? What should donors consider when coordinating an investment and distribution policies? Is it necessarily imprudent for an endowment-style DAF to have an equity allocation of 100% (or more)? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!

This breaks my heart. DAFs are subsidized by taxpayers who are expecting that money to be put to use to help environmental or social problems. This money should be put out to have impact sooner rather than later and by people who care about these issues as opposed to whoever inherits it.

This breaks my heart. Money given to DAFs is subsidized by taxpayers who expect this money to be given to environment or social problems. This money should be used for impact sooner rather than later. Saving this money indefinitely to be given away by whoever inherits it rather than those passionate and knowledgable is problematic. DAFs need regulation. Endowed DAFs should be illegal.