Executive Summary

With the implementation date of the Department of Labor’s fiduciary rule looming large in April, all attention has been focused on how financial advisors and their Financial Institutions are making adjustments to manage their compensation conflicts of interest, to avoid breaching the fiduciary’s fundamental duty of loyalty to act in the client’s best interests.

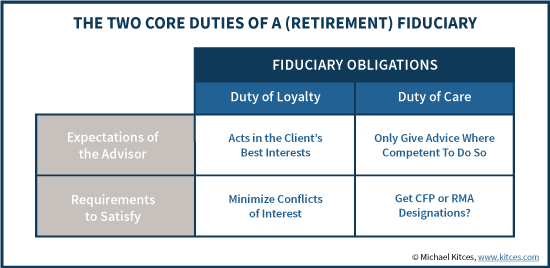

However, the reality is that being a fiduciary actually entails two core duties: the first is the duty of loyalty (to act in the client’s best interests), and the second is the duty of care (to provide diligent and prudent advice, and only in areas in which the advisor is competent to provide such advice). After all, a fiduciary obligation is relatively meaningless with only a duty of loyalty, if there’s no expectation of competency; otherwise, consumers would still be harmed by unwitting negligence, even if there was no intentional (or conflicted) self-enrichment.

And the distinction matters, because the Department of Labor’s Best Interests Contract Exemption attaches a fiduciary obligation to the Financial Institution itself, including the potential for a class action lawsuit against the institution for failing to meet its fiduciary obligations. Which means a Financial Institution could face a class action lawsuit not only for systemic breaches of the fiduciary duty of loyalty (e.g., by utilizing too much conflicted compensation), but also by systemically breaching the fiduciary duty of care but not sufficient training their advisors.

In other words, Financial Institutions face the risk that they will be sued in a class action lawsuit for failing to put their financial advisors through the training and education (e.g., professional designations) necessary to ensure that the advisor would even know what the “best” advice for the client was in the first place!

Unfortunately, right now there actually is no universally accepted minimum competency standard for financial advice (or in the case of DoL fiduciary, retirement advice), though certainly recognized rigorous designations that include both education and an advice process – such as the CFP Board’s CFP certification, and RIIA’s RMA designation – provide a likely path of safety for Financial Institutions. Which means in the coming year, there may soon be explosive growth in programs like the CFP and RMA, as Financial Institutions recognize and then try to minimize their exposure to a class action lawsuit for failing to meet the fiduciary duty of care.

The Two Core Duties Of A Fiduciary: Loyalty, And Care

The concept of a fiduciary duty spans more than just financial advice. The lawyer has a fiduciary duty to the client. A trustee has a fiduciary duty to the trust beneficiaries. A (corporate) board of directors has a fiduciary duty to the shareholders.

Although the exact application of fiduciary duties vary slightly based on context, they all typically entail two core duties.

The first is that a fiduciary owes a duty of loyalty (e.g., to clients, beneficiaries, or shareholders). The duty of loyalty is to serve the client first and foremost, rather than the fiduciary serving themselves; in other words, to act in their clients’ best interests. In the context of a fiduciary duty for financial advisors in particular, the ability to receive commissions presents the possibility that the advisor could be enriched at the expense of the client, rather than in his/her interests; as a result, advisors subject to a best interests standard are expected to disclose and minimize, or ideally avoid altogether, any conflicts of interest that could compromise the advisor’s ability to fulfill the duty of loyalty.

However, the reality is that there’s actually a second core duty that a fiduciary must fulfill as well: the duty of care. In essence, the duty of care requires that the fiduciary conduct appropriate due diligence, and make decisions in a prudent manner. Or viewed another way, the duty of care says that to serve as a fiduciary, you have to be competent enough to give fiduciary advice, and if not a core competency, to engage outside experts as necessary to substantiate that an appropriate best interests recommendation is being made.

Logically, the two duties actually should go hand in hand. After all, it makes little sense to require fiduciaries to exhibit a duty of loyalty to act in the best interests of the client, if the fiduciary doesn’t have the competency to know what’s in the client’s best interests in the first place. A fiduciary duty of loyalty without the associated duty of care would simply mean consumers are harmed by unwitting negligence rather than intentional (or conflicted) self-enrichment.

Which means, simply put, to actually deliver fiduciary recommendations the advisor must not only try to provide advice in the client’s best interests, but also ensure that he/she is competent enough to give that advice (or to appropriately vet and utilize experts who have the requisite expertise).

The Duty Of Care Under DoL Fiduciary

Recognizing that there are two core duties of a fiduciary – loyalty, and care – is not just an idle theoretical exercise. In the context of the Department of Labor’s fiduciary rule, both are implicitly recognized in the requirements of the Best Interests Contract Exemption.

After all, the core requirement of the Best Interests Contract is that advisors must adhere to “Impartial Conduct Standards”, which stipulate that the advisor must give Best Interests advice, for Reasonable Compensation, and make no (materially) misleading statements.

In defining the specific expectations of the advisor’s advice, though, the Department of Labor states that:

"When providing investment advice to the Retirement Investor, the Financial Institution and the Adviser(s) provide investment advice that is, at the time of the recommendation, in the Best Interest of the Retirement Investor."

This statement, taken directly from the final rule, is a direct expression of both the Duty of Loyalty (that advice be in the Best Interests of the Retirement Investor), and also the Duty of Care (that the advice reflect the “care, skill, prudence, and diligence” that any other expert would have applied in a similar circumstance). Or viewed another way, if the advisor doesn’t have the knowledge and skills to be prudent and diligent, it’s not possible to fulfill the advisor’s fiduciary duty of care under the Department of Labor rules.

These dual fiduciary duties matter in the context of the Department of Labor’s rule in particular, because one of the key requirements of the Best Interests Contract Exemption is that Financial Institutions cannot exclusively limit consumers to mandatory arbitration in all circumstances. While any individual advisor/client incident can still be bound to arbitration, the DoL requires as a condition to qualify for the Best Interests Contract Exemption that consumers collectively still be allowed to sue the Financial Institution in a class action lawsuit.

Which means if a Financial Institution systemically violates its fiduciary obligation across the entire firm – either by not satisfying the duties of loyalty and care, and/or not overseeing and ensuring that the advisor meets those standards –it runs the risk of a very big class action lawsuit!

The Real Class Action Lawsuit That Looms Under DoL Fiduciary

Notably, the reality is that the compliance departments of many Financial Institutions have already been fretting the risk of a class action lawsuit. It’s one of the single most feared (or even loathed) provisions of the Department of Labor’s fiduciary rule for a large financial institution, because it dramatically raises the stakes of a potential systemic failure to fulfill the firm’s fiduciary duty to clients, outside the relative safety of one-advisor-at-a-time arbitration (especially industry-friendly FINRA arbitration).

On the other hand, thus far the focus of fulfilling the Financial Institution’s fiduciary obligation has been focused almost entirely on the duty of loyalty, from minimizing conflicts of interest by adjusting compensation grids and modifying recruiting contracts, to adjusting product shelves in an effort to eliminate differential compensation across products, and in some cases even choosing to pivot the entire Financial Institution to become a Level Fee fiduciary.

But this focus on managing exposure to potential fiduciary breaches of the duty of loyalty has completely missed that Financial Institutions are also exposed to failures in executing the fiduciary duty of care!

In other words, imagine what happens when a class action plaintiff’s attorney comes along to a mid-to-large-sized broker-dealer and says:

“Explain to me how your brokers would know what the “best interests” advice is for the client? What training and education have they had to establish the necessary technical competency, and what process were they trained in to ensure their advice reflects the care, skill, prudence, and diligence that a similar expert would have applied in a similar situation?”

For which the broker-dealer says… what?

“In order to deliver best-interests advice about a retiree’s life savings, we require our advisors to have a high school diploma*, and take a 3-hour regulatory exam (either the Series 6 or perhaps the Series 65)?

*But the high-school diploma is actually just optional.”

The unfortunate reality is that the standard FINRA regulatory exams do not actually provide the kind of training and education necessary to establish actual technical expertise (or even basic competency) regarding retirement advice. The Series 6 (or Series 7) are really just licensing exams to affirm that someone is legally allowed to sell various types of securities products; the Series 65 is designed primarily to ensure that investment advisers know the state and Federal laws that will apply to them. Neither train advisors in a process of evaluating client needs, nor provide them the technical competency to necessarily know which solution would be best in the first place.

Ironically, the Series 65 has been the minimum regulatory exam for Registered Investment Advisers for a long time, and RIAs have been subject to a fiduciary standard for a long time… and this disparity has been allowed to continue, despite the fact that the Series 65 doesn’t really provide much education to satisfy the fiduciary duty of care. However, from a practical perspective, any such breaches in the past would have still only been individual lawsuits with a particular advisor – and likely bound to arbitration. It’s only under the Department of Labor’s fiduciary rule that the fiduciary duty is not just an obligation of the advisor but also the Financial Institution, and it’s only under the DoL rule (unlike the Investment Advisers Act) that fiduciary breaches must have the opportunity to escalate to class action status.

Which means, for the first time ever, Financial Institutions can be sued in a class action lawsuit for the lack of technical competency of their entire base of brokers. And with the DoL fiduciary rule effective date looming large in April of 2017, large broker-dealers may suddenly transition hundreds or even thousands of brokers into a new fiduciary obligation, all at once, with only perhaps some sales and product training, but not the training and education necessary to be capable of fulfilling their fiduciary duty of care!

What’s The Minimum Competency Standard For Financial Advice?

So given this dynamic, the question that arises for any Financial Institution facing DoL fiduciary implementation in April: what is an acceptable, defensible minimum competency standard to ensure a financial advisor is capable of giving best interests advice?

Notably, the key distinction here is not merely a question of raw technical knowledge alone. As a key part of the duty of care is not just “knowing stuff”, but having a process to substantiate that the fiduciary duty was executed appropriately. Accordingly, safe harbors of technical competency to meet the duty of care will likely be designation programs that teach not just the raw technical knowledge, but some kind of “advice process” as well.

For instance, CFP certification doesn’t just cover the breadth of its 72 principal knowledge topics; it also teaches the 6-step financial planning process as the core of its Financial Planning Practice Standards, to better substantiate that the advisor actually did his/her diligence in evaluating the client’s situation before making a prudent recommendation.

Arguably, an even more robust solution would be RIIA’s Retirement Management Analyst (RMA) designation, which also includes the use of its Retirement Procedural Prudence Map. The RIIA Procedural Prudence Map is the very essence of demonstrating the fiduciary advisor met his/her duty of care, with an in-depth process for validating why a particular retirement recommendation would be given (along with the supporting technical education to make the advisor competent enough to navigate the relevant decisions). This is an important distinction from even other retirement designations like the RICP or CRC, which don’t include the process tools that the RMA does.

In other words, it’s the combination of competency education, and a prudence process, that is necessary for an advisor to substantiate that he/she actually met the fiduciary duty of care (and not just the duty of loyalty).

At a minimum, though, the potential for a duty-of-care-based class action lawsuit could mean fresh scrutiny on the reams of lightweight or entirely “bogus” designations that still exist in the advisor marketplace, which appear to be on the decline with the rise of more credible designations (as there’s no reason to add a specious designation after getting a recognized one like CFP certification). As it stands, there are still surprisingly few designations that have ever been through any kind of stringent accreditation process (notable positive exceptions being IMCA’s CIMA certification with ANSI, and the CFP Board's accreditation with NCCA).

In other words, the issue of a designation’s credibility – especially given how many don’t have any accreditation or other means to substantiate and validate their program – will face greater scrutiny after DoL fiduciary, as Financial Institutions try to evaluate what will be a defensible designation to substantiate the advisor was trained enough to meet the Duty of Care. An advisor who is sufficiently trained and still fails to follow the process is the advisor’s fault; a Financial Institution that fails to train all of its advisors with a credible training program is a potential class action lawsuit.

The bottom line for Financial Institutions, though, is that while all eyes have been on the fiduciary duty of loyalty, arguably firms should also be taking an aggressive focus, now, on getting their advisors enrolled into a program that can actually substantiate that they are competent enough to give best-interests advice in the first place. Otherwise, the Financial Institutions may prevail in defending that their advisors meet the fiduciary duty of loyalty, but leave themselves a large class action lawsuit target for failing to meet the fiduciary duty of care.

Which, in turn, should be a substantial boon in the coming years to organizations like CFP Board, RIIA, and IMCA, which have focused for years on creating high-caliber designations, often accredited and/or backed by a legitimate advice process to substantiate the advisor’s due diligence (and further lifting their standards over time), which in a class action lawsuit could become enshrined as the recognized minimum standard for financial advisor competency (at least or especially when it comes to retirement advice) as financial planning slowly becomes the embodiment of fiduciary financial advice from the inside out.

So what do you think? Are too many firms focusing on the fiduciary duty of loyalty but ignoring the duty of care? What is the minimum competency standard for giving financial advice? Will DoL fiduciary be a boon for designations like the CFP and RMA? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!

Yes. The rule provides specifically for: “prudent advice that is based on the investment

objectives, risk tolerance, financial circumstances, and needs of the

Retirement Investor…” This can’t be accomplished without going through some semblance of a plenary financial planning process. Which, as you argue persuasively, can’t be accomplished without both some training and some tools.

The other point which is an aside to these points is the idea that the potential for class action will increase when there is a meaningful drop in the market. Although it does specifically read in the DOL regulations, a drop in market will cause many investors to trigger a call to attorneys who promote collection of loss investments. So a classic up and down market cycle will create a great potential for litigation for even the most responsible advisor. This is out of our control, and really sucks.

The upside I see is the value and promotion of the CFP(r) and financial planning process. But the previously mentioned risk makes this a moot point.

With all this concern about meeting a “standard of care,” no mention regarding the role of a qualified attorney and/or CPA? Make no mistake about, there are elements of the DOL Fiduciary Rule that would require the services of either of these professionals. I am confident that further explanation for raising this concern should not necessary. D. Sterling, Esq., Consultant

If the upshot of the whole process is that slavishly applied adherence to MPT becomes a de facto necessity, the consumer will have been very poorly served, indeed. There must be room for contrarian investing.

Contrarian investing and MPT are perfectly consistent. So long as the contrarian turns out to be right.

Michael, Thank you for highlighting technical competency in the rendering of advice. Technically, under the suitability standard, brokers do not render advice., Tthey just make investors aware of their investment alternatives. No advice is implied or rendered, thus no fiduciary liability is assumed. It is up to the consumer to determine investment meriy on their own regardless how limited their investment knowledge and experience may be. This issue is ripe for litigation under a “prudent expert” fiduciary standard. It requires the brokerage/custody industries to (1) adopt prudent process (asset/liability study, investment policy, portfolio construction, performance monitor) authenticated back to objective, non-negotiable fiduciary criteria, (2) retooling of product menus to facilitate real time client holdings data and streamline cost, and (3) assurance of professional standing and the guarantee of consumer protections long denied to “retail investors”. SCW

Michael, Thank you for your thorough and very good explanation of the distinction between a fiduciary’s duty of loyalty and duty of care. I certainly agree that training via a credible retirement designation program can be at least one of the answers for how the industry can help advisors meet the duty of care element of the DOL rule.

I also strongly agree that an important way to determine a designation program’s credibility is whether or not it is independently accredited. Accreditation for a professional certification provides impartial, third-party validation that the program has met recognized credentialing standards for development, implementation, and maintenance of the program. Very few designations are accredited because

it is very difficult to meet these rigorous standards. Out of the 170 designations listed on the

FINRA website, only 7 are shown to be independently accredited. They not only include CFP and CIMA, but the CRC as well.

I’d also like to assure your readers that, working with our academic partner Texas Tech University, the CRC program was created in 1997 to ensure that certificants meet a minimum competency standard for fulfilling their responsibilities as retirement counseling professionals. To be certain that the CRC examination is testing the most up-to-date and relevant concepts and to meet accreditation requirements, InFRE conducts a detailed practice analysis of all channels of the retirement planning profession no less than every five years. The resulting Test Specifications contain the procedural oriented domains of practice and associated tasks and knowledge statements which are the basis for the CRC examination.

The CRC also distinguishes itself from other retirement designations in that it covers both retirement income and accumulation planning. In particular, the CRC distribution planning curriculum also helps retirement professionals apply a consultative process oriented approach when helping clients make informed retirement planning decisions.

Kevin,

Thanks for sharing this, and expanding my knowledge on the CRC’s accreditation! 🙂

I’ve tagged your comment as “Featured”, so future readers of the article will be able to easily find and view this information as well!

– Michael

Michael: excellent piece here and quite prescient. Why do you think so little attention is paid to the Duty Of Care?

Is it too big a a problem to fix?

Getting every FA in a fiduciary role to get a CFP, RMA etc is an awfully expensive solution. Maybe the regulators think it is impractical.

Nevertheless, something needs to be done for the Duty of Care or it will have no integrity.

Michael – you do an excellent job of laying out the risk/reward for the Duty of Care. Getting so many advisors accredited seems potentially impractical. We suggest another, parallel solution that is much more cost-effective and scalable. WealthManagement.com featured our proposal here: http://www.wealthmanagement.com/industry/practical-solution-fulfilling-duty-care