Executive Summary

The traditional view of work is that it’s something we wouldn’t otherwise do, without the financial reward of getting paid… such that the whole point of work in the modern era is to earn and save enough to get to the point where you can “retire” and not need to work anymore.

Yet research on what actually motivates us reveals that “money” is a remarkably inferior motivator (both to incentivize and reward desired behavior, and to punish bad behavior) compared to the motivation we derive from interpersonal relationships with other people. To the point that turning social connections into financial arrangements can reduce our motivation to engage in the desired behaviors. Yet due to our inability to judge our own motivations, and what will make us happy in the future, we continue to pursue financial rewards… even as a growing base of research reveals that it doesn’t actually improve our long-run happiness.

The reason why all of this matters is that it implies the whole concept of “retirement” may be predicated on a mistaken understanding of our own motivators… a realization that most people don’t have until they actually retire (or at least, are on the cusp of it), and suddenly discover that “not working” isn’t nearly as enjoyable as expected, despite all the sacrifices of potentially undesirable work that was done to earn the money to retire along the way.

So what’s the alternative? To recognize that work – at least, some work – can be intrinsically motivating and socially rewarding, where money doesn’t have to be the driving factor. Yet at the same time, often such work does at least have some financial rewards… which is important, because if “retirement” is simply about shifting the rewards of work from “mostly financial” to “only partially financial”, then the reality is that most people may not need nearly as much to “retire” in the first place. And that the very nature of “retirement” itself isn’t really about an end to working, but simply reaching the point of financial independence where “work” can be chosen based primarily (though not exclusively) for its non-monetary rewards!

Is Money Really An Effective Reward To Motivate Work?

The conventional view of money is that it is a highly effective motivator, particularly for what is otherwise the “unpleasant” task of work. Thus, workers are paid compensation and bonuses to incentivize and motivate them to do more work (and achieve sometimes-challenging tasks). And ultimately, the presumed goal is to accumulate enough of the rewards (money) to no longer need to do the tasks (work) in the first place, and therefore be able to retire.

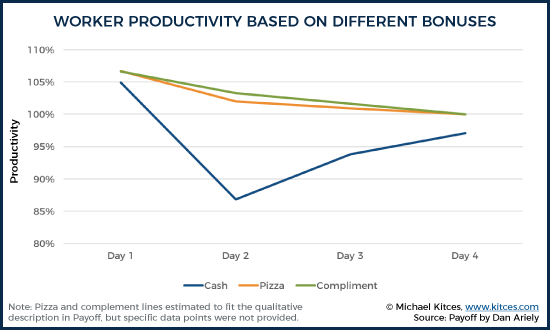

The results revealed that that all three of the potential “bonuses” – cash, pizza, and a compliment – served comparably well to motivate on the first day, with the pizza boosting productivity by 6.7% that day, the prospective compliment generating a 6.6% boost, and the potential cash bonus coming in last (but only slightly) with a 4.9% productivity boost. However, on the subsequent day of the four-day work cycle, those who received the money performed 13.2% worse than the control group as the prospective benefit of the money wore off (and they were still 6.2% less productive on day 3, and 2.9% less productive on day 4!), such that cumulatively for the week, those who earned the cash bonus ended out being 6.5% less productive! By contrast, though, those who had received the pizza reward remained slightly more productive for the week (drifting back towards the control group as the days went by), and those who received the compliment had the highest overall productivity for the week (though they still drifted back to the control group’s productivity by the end for the four-day series of shifts).

In other words, the highest cumulative productivity came from those who received a compliment from their boss as a bonus, while the more financially oriented the reward, the less the money sustained any kind of motivation for increased productivity! Which means, to say the least, money alone is clearly not our only – nor even perhaps our primary – motivator, and making rewards more financially oriented can actually reduce motivation in the long run (as the productivity enhancements stop, or even ‘rebound’ to the negative, the moment the cash bonuses go away!).

And the prospective adverse impact of turning an interpersonal social reward into a financial one is not unique to situations like semiconductor factory workers. For instance, Ariely also presents the following thought experiment as well… imagine you are at your mother-in-law’s house, having just had a sumptuous and delicious Thanksgiving dinner with the family, and at the end of dinner you pull out your wallet and say “Mom, for all the love you’ve put into this family dinner, how much do I owe you? Will three hundred dollars do it? Or four hundred?” Would introducing a financial “reward”, beyond simply expressing your gratitude for a family dinner prepared with love and care, really be a “bonus” to your mother-in-law, or just help to remind everyone how inappropriate it is to try to put a price on the priceless nature of family love?

Social vs Monetary Punishments To Stop Bad Behaviors

Notably, these dynamics between monetary versus social motivators (e.g., the cash versus the compliment, expressing gratitude versus paying for a Thanksgiving family dinner) exists not only in the context of rewards to incentivize “good” behavior and work productivity. A similar effect occurs with respect to punishments to disincentivize or punish bad behavior, too.

For instance, researchers Uri Gneezy and Aldo Rustichini conducted a study looking at how to encourage parents to pick up their children on time from day care centers (or alternatively, how to discourage them from the ‘bad behavior’ of being late for pick-ups). In general, most parents were on time, but late arrivals past the official 4PM pick-up did occur from time to time.

Accordingly, the researchers introduced a fine, of approximately $3 for every 10 minutes that the parents were late. Thus, rather than simply rely on the goodwill of the parents to not inconvenience the day care center workers by being late, a financial punishment was introduced as well.

The results: once the penalty was introduced, the rate of parent tardiness more than doubled. In other words, parents were more willing to be late for a known cost of $3 per 10 minutes, rather than just the unknown-but-implied inconvenience of forcing the day care workers to stay late to wait for the pick-up.

In essence, the financial cost of the late penalty was viewed as a lesser consequence than one solely focused on the implied social contract between the parents and the day-care workers of “we close at 4PM, please be courteous and pick your children up on time.” Introducing the financial consequence turned the arrangement from a social agreement, into a financial one with a clear (and deemed to be affordable) cost – pay $3, and be absolved of any social guilt for being late. And notably, the researchers found that once the cost of being late was “set” in the minds of the parents, it persisted; even after the penalty was later removed, the parents continued to be late just as often, at double the rate they were originally, because the financial price had been “set” in their minds (and deemed an acceptable trade-off to them) at that point.

All of which goes to show that once again, the social connection between human beings can impact behavior even more than pure monetary rewards or fines/punishments. And turning a social agreement into a mere financial arrangement can actually undermine the behavioral motivation to “do the right thing”!

Predicting What We Find Rewarding: Intrinsic vs Extrinsic Motivation

Notwithstanding this dynamic that money isn’t always a great motivator (or an effective tool for punishment), one of the great challenges of motivation is that we think such extrinsic motivators – like getting a bigger paycheck, or earning a nice bonus – will feel rewarding (and that a financial penalty or fine will similarly punish and stop bad behavior). Even though when the time comes, it turns out that we’re much more motivated by intrinsic motivators (e.g., whether we actually enjoy the work and find it immersive) and social dynamics (e.g., whether the boss compliments us, or more generally whether the engagement deepens our relationships, or not wanting to let someone down based on what we have already implicitly or explicitly agreed to do).

Which matters, because from the financial planning perspective, this has rather profound implications for the real-world trade-off decisions we make about job choices and income, earning more to save more, and the very nature of retirement itself.

For instance, research by Daniel Kahneman and Angus Deaton finds that higher income is not associated with greater happiness, beyond a threshold level of about $75,000/year in household income (with perhaps some variability for cost-of-living in certain parts of the country). However, their results indicate that higher income beyond this threshold is associated with higher scores of self-reported life satisfaction. In other words, while people with higher levels of income claim to feel more satisfied with their lives, when their actual positive and negative emotions are measured on a daily basis, they aren’t actually any happier for it!

Similarly, a 2009 Bankrate Financial Literacy poll found that a whopping 75% of consumers plan to work as long as they can. In some cases, it’s because they actually need the money, but in the majority of cases, it’s simply because they actually state that they like to work. And ostensibly, the percentage who stated they will keep working because they need to might also find that they would work because they enjoy it, too… if they actually did have enough money, and could stop working in a job that was primarily about the money, and instead tried to find work that was more intrinsically motivating, too?

Financial Independence And The Freedom To Pursue The Non-Monetary Rewards Of Work

To say the least, what all of this Finology research suggests is that our relationship with money is far more complex than just the idea that we work to earn money, and earn money so we will no longer need to work. Because in reality, the intrinsic motivation and social rewards of “work” can be even more important and powerful than the extrinsic motivation of monetary rewards. We may think that the latter (money) will be more motivating, but once we get there, it rarely is.

Thus why we say we want a financial bonus to incentivize our long-term behavior, but then end up producing far less the moment after the bonus is paid. And why we say we want to generate money to pursue retirement and a “non-work” phase of life, but then when we stop working we find out it’s not as enjoyable as we thought (as we lose our identity and purpose, and reason for getting up in the morning), and thus end up going back to work anyway (but perhaps for non-monetary rewards).

Of course, financial constraints are a reality in the real world, and there are many people who can’t afford to just live to work (for non-monetary rewards) and instead must work to (afford to) live. Nonetheless, what all of this research implies is that at best, working for money is still not about retiring from work, it’s simply about gaining “financial independence” that makes it feasible to shift the priority of work to non-financial rewards, instead.

First and foremost, this is important to consider for those who strongly dislike their current jobs, but have been doing the work anyway in an effort to earn enough money to pursue a retirement that potentially won’t actually make them much happier anyway. Perhaps switching to more personally rewarding work, for less money, would be a good idea… especially if doing less-enjoyable work for more money is only to pursue a “retirement” goal that may not actually make you happy anyway.

Even more significant, though, is the simple recognition that “non-financial work” does often (though admittedly not always) end up having some kind of financial reward anyway. While the financially independent retiree might simply volunteer at church, or become a mentor, or engage in a new hobby, often in practice that turns into some part-time paid work, or a business consulting agreement, or a new business opportunity.

Which matters, because if there actually is likely going to be at least some modest financial reward coming from mostly non-monetary work, it actually means many prospective “retirees” could make the switch to meaningful non-monetary work even sooner! After all, at a 4% withdrawal rate, making “just” an extra $10,000/year in part-time work in retirement can reduce the retirement savings need by as much as $250,000! And making just $40,000/year in “retirement” can shave a cool $1,000,000 off the required nest egg!

Nonetheless, as human beings, our brains do appear to be hard-wired to pursue rewards (and avoid punishments). And that drive to pursue rewards, combined with our ability to delay gratification, creates our capacity to do “work” today in order to generate the (financial) rewards that allow us to not work later. Yet recognizing that a significant portion of our rewards are social and interpersonal (and non-financial), and that we can be intrinsically motivated as well, helps to reveal why so many end up continuing to “work” even after it’s no longer financially necessary. Which is crucial to understand, because planning for work after we reach financial independence can actually make it financially possible for us to make the transition even sooner!

Which means in the future, perhaps the real question to ask is not “how much do you need to retire”, but “what kind of work would you pursue for non-monetary rewards if you were financially independent and didn’t need the money… and how much money would you likely end up earning from that effort anyway?” And then plan accordingly!

So what do you think? Is money really an effective reward to motivate work? Are we bad at predicting whether we will be motivated extrinsic or intrinsic rewards? Is our ultimate financial goal to be able to pursue work for non-financial rewards? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!

Great article that summarizes the best we have available on the current research on this topic. The bottom line is that we are very bad at predicting what will make us happy. It’s much better to look at the research instead of going with our intuition on this one. For example, buy the smaller house closer to work to limit your commute even though you think the nicer house will make you happier….research says it won’t but the commute will certainly lower your happiness. They are lots of other examples.

Another tip from research on motivation is that it’s linked to three fundamental attributes. Autonomy, belonging (is there a strong social connection?), and competency (are you good at something and are you improving?). If your “work” and life includes more of these elements, you’ll be more engaged, motivated, and happy.

I expect financial planners will need to focus on this stuff more in the future to compete with the automated programs that can handle the easier numbers part. This is where the human interaction shines. Maybe a new term will be needed? Financial planning psychologist? Financial life coach?

Thanks again and keep up the good work!

This is an outstanding article that addresses life issues that are real and on point. Might be your best article yet. Keep up the good work.

I had a couple of quick thoughts as I read this article:

1. Highly paid workers should not ignore the freedoms which come with higher incomes and what some have described as “oversaving”. Once my wife and I had a significant nest egg and a large emergency fund, we realized real joy from having zero debt and zero financial stress. We weren’t saving just for retirement but also for pre-retirement financial freedoms.

2. Changing careers is very risky. I don’t think one can really know whether a new career will be personally rewarding, boring as hell, or stressful in ways not imagined until he is totally immersed in it. Trying out a new job parttime or on weekends is just not enough to make a judgment about how that career will fit one’s life after it becomes a fulltime commitment.

Changing careers at 30 is much less risky than doing so at 48. I did both. I discovered that one can easily reverse the decision at age 33 (although I did not do so). Reversing a career decision after age 50 is damned hard. I have known others who also had this experience.

Nice job tackling this mind-boggling topic. I’d add that one should be careful of pursuing their dream avocation — in my case writing — as a semi-vocation because soon it can become a vocation that takes more time and work than “work” ever did.

My experience corroborates the research. I retired comfortably at 62 from a career as a pastor. I wanted to invest my time helping others. The original plan was to provide free financial literacy seminars. Deciding that I needed greater competency and credibility, I began taking CFP training. That led to establishing my own firm as a way to gain required experience. So now I work almost full time to complete my experience requirement with the plan to scale back in the years ahead. I want to cover expenses and a little more. The death of my spouse after completing my training led to focus on helping surviving spouses and those who became a divorcee near retirement age. Greater income does not motivate me as I already have sufficient income.

I also resonate with saveinvestbecomefree who highlighted autonomy, belonging and competency as key motivating factors. I enjoy my second career in “retirement” as it includes these three and also fulfills the desire to help others find financial wholeness. For me, financial wholeness means having enough, not being affluent.

Great article, and

especially timely as our society redefines the nature of work in the

years ahead. As robots and AI start doing more of the required labor,

and more of the white collar work, who needs to work, for how many hours

per week and for how many years?

Will

we adopt a Universal Benefit to give all the non-workers enough money

for a minimally acceptable standard of living? What will we think of

those individuals who would (really) like to work, but for whom there is

not enough work to go around?

And

what will we think of the full time workers? Will somebody be

considered greedy for working a 40 hour week? When I was in college I

worked nights on a freight forwarding platform, and being young and

eager to please, I really put in a lot of effort. One of the older

(union) guys took me aside and said: “Hey kid, leave some work for the

day shift.”

Michael,

Yes. As much was said decades ago by the great management guru, W. Edwards Deming. He observed that pay is not a great motivator (but can be a de-motivator).

He had the idea of “intrinsic motivation”, that people innately work to do their best, and that external motivations (pay, threats from your boss) are much less effective as positive motivations.

Keith

Great comments. I no longer work in my corporate tax role. While I am not a totally reformed accumulator, I did realize that staying in corporate tax would only shorten my life expectancy and reduce my health, not to mention keeping me from other interests. Like John, I am going into financial planning for the social interaction and hopefully to add social value. I am lucky and do not require cash flow from the labor market. I am working part-time at my friends CPA firm and teaching accounting while I go through the CFP program at CLU.

The strange observation that I have made that most of us part timers are the lucky ones: We have the health, education and skills that allow us to still participate in the labor market. Further, most of us are also have retirement adequately funded. Sad in a way, but I do not believe in socialism.

I hope to be able to help the 50 plus crowd make the late stage moves that will turn a marginal “retirement” into a success. At least that is the plan if I can find the clients who need me.

Excellent article, Michael. Spot on, and echoes many of the conversations I have with my clients