Executive Summary

After a nearly 18-month process of working to update its Standards of Professional Conduct, the CFP Board’s Commission on Standards has released newly proposed Conduct Standards for CFP professionals, expanding the breadth of when CFP professionals will be subject to a fiduciary duty, and the depth of the disclosures that must be provided to prospects and clients.

In fact, the new CFP Board Standards of Conduct would require all CFP professionals to provide a written “Introductory Information” document to prospects before becoming clients, and a more in-depth Terms of Engagement written agreement upon becoming a client. In addition, the new rules also refine the compensation definitions for CFP professionals to more clearly define fee-only, limit the use of the term fee-based, and updates the 6-step “EGADIM” financial planning process to a new 7-step process instead.

Overall, the new Standards of Conduct appear to be a positive step to advance financial planning as a profession, more clearly recognizing the importance of a fiduciary duty, the need to manage conflicts of interest, and formalizing how CFP professionals define their scope of engagement with the client.

Ironically, though, the CFP Board’s greatest challenge in issuing its new Standards of Conduct is that the organization still only has limited means to actually enforce them, as the CFP Board can only make public admonishments or choose to suspend or revoke the CFP marks, but cannot actually fine practitioners or limit their ability to practice. And because the CFP Board is not a government-sanctioned regulator, it is still limited in its ability to even gather information to investigate complaints in the first place, especially in instances where the complaint is not from a client but instead comes from a third party (e.g., a fellow CFP professional who identifies an instance of wrong-doing).

In addition, the CFP Board’s new Standards of Conduct rely heavily on evaluating whether the CFP professional’s actions were “reasonable” compared to common practices of other CFP certificants… which is an appropriate peer-based standard for professional conduct, but difficult to assess when the CFP Board’s disciplinary proceedings themselves are private, which means CFP professionals lack access to “case law” and disciplinary precedents that can help guide what is and is not recognized as “acceptable” behavior of professionals. At least until/unless the CFP Board greatly expands the depth and accessibility/indexing of its Anonymous Case Histories database.

Nonetheless, for those who want to see financial planning continue to advance towards becoming a recognized profession, the CFP Board’s refinement of its Standards of Conduct do appear to be a positive step forward. And fortunately, the organization is engaging in a public comment process to gather feedback from CFP certificants to help further refine the proposed rules before becoming final… which means there’s still time, through August 21st, to submit your own public comments for feedback!

CFP Board Commission On Standards Proposes Revised CFP Code Of Ethics And Standards Of Conduct

Back in December of 2015, the CFP Board first announced that it was beginning a process to update its Standards of Professional Conduct, by bringing together a new 12-person “Commission on Standards” (ultimately expanded to 14 individuals), including diverse representation across large and small firms, broker-dealers and RIAs, NAPFA and insurance companies, and even a consumer advocate and former regulator.

The purpose of the new group was to update the CFP Board’s existing Standards of Professional Conduct, which is (currently) broken into four key sections:

– Code of Ethics and Professional Responsibility: The 7 core ethical principles to which all CFP certificants should aspire, including Integrity, Objectivity, Competence, Fairness, Confidentiality, Professionalism, and Diligence

– Rules of Conduct: The specific rules by which the conduct of CFP professionals will be evaluated, including a CFP certificant’s obligations to define the client relationship, disclose conflicts to the client, protect client information, and the overall duty of conduct of the CFP certificant to the client, to employers, and to the CFP Board itself.

– Financial Planning Practice Standards: The standards that the CFP certificant should follow that define what financial planning “is” and how the 6-step financial planning process itself should be delivered.

– Terminology: The definitions of key terms used in the Standards of Professional Conduct, from what constitutes a “financial planning engagement” to what it means to be a “fiduciary” and the definition of “fee-only” and what is considered “compensation” to be disclosed.

The update process would be the first change to the CFP Board’s Standards of Professional Conduct since mid-2007, which at the time was highly controversial, and stretched out for years, but culminated in the first application of a fiduciary duty for CFP professionals.

Under the newly proposed Code of Ethics and Standards of Conduct, which the CFP Board published for public comment last Tuesday, June 20th, the four sections above will be consolidated into two sections – a Code of Ethics, and a Standards of Conduct (which will incorporate the prior Rules of Conduct, Practice Standards, and key Terminology).

The full text of the Proposed Code of Ethics and Standards of Conduct can be viewed here on the CFP Board’s website.

Expanding The Fiduciary Definition Of “Doing” Financial Planning

Under the CFP Board’s current Rules of Conduct for CFP professionals, certificants owe to their clients a fiduciary duty of care when providing financial planning or material elements of financial planning. Accordingly, the reality is that the overwhelming majority of CFPs are already subject to a fiduciary duty when providing financial planning services to clients.

However, the CFP Board’s standard has been criticized as allowing for a “loophole”, in that it’s not based on simply being a CFP professional, but instead tries to identify when people are doing financial planning (or material elements thereof). Which at best isn’t always clear, and at worst allows a subset of CFP professionals to aggressively sell nothing but their own products – knowingly not serving as a fiduciary, despite holding out as a CFP certificant – because a single product recommendation was not deemed to be “doing financial planning”.

New CFP Board Fiduciary Duty When Providing Financial Advice

In its new CFP Code of Ethics and Standards of Conduct, the CFP Board takes a stronger position that CFP certificants should be held to a fiduciary standard when delivering their services. Accordingly, the very first section of its new Standards of Conduct states:

A CFP Professional must at all times act as a fiduciary when providing Financial Advice to a client, and therefore, act in the best interest of the Client.

Notably, under this new rule, the scope of fiduciary obligation is not limited to just when providing “financial planning” or “material elements of financial planning”. Instead, the fiduciary duty will apply anytime a CFP professional is “providing financial advice”, which itself is defined very broadly, as:

Financial Advice (according to CFP Board)

A) Communication that, based on its content, context, and presentation, would reasonably be viewed as a suggestion that the Client take or refrain from taking a particular course of action with respect to:

- The development or implementation of a financial plan addressing goals, budgeting, risk, health considerations, educational needs, financial security, wealth, taxes, retirement, philanthropy, estate, legacy, or other relevant elements of a Client’s personal or financial circumstances;

- The value of or the advisability of investing in, purchasing, holding, or selling Financial Assets;

- Investment policies or strategies, portfolio composition, the management of Financial Assets, or other financial matters;

- The selection and retention of other persons to provide financial or Professional Services to the Client; or

B) The exercise of discretionary authority over the Financial Assets of a Client.

In this definition, the mere suggestion that a client take or refrain from taking any particular course of action is deemed “financial advice”. Notably, the CFP Board does clarify that marketing materials, general financial education materials, or general financial communication “that a reasonable person would not view as Financial Advice” does not constitute Financial Advice. Nonetheless, most classic recommendations – from delivering a comprehensive financial plan, to merely suggesting “this product is right [or not right] for your situation”, would be captured under this definition of Financial Advice, and subjected to a fiduciary duty.

In other words, the expansion of the CFP Board’s application of the fiduciary duty to providing any kind of “financial advice”, and not just delivering “financial planning or material elements of financial planning”, eliminates the current gap where product salespeople could sell a product as a CFP certificant and claim they’re not subject to the fiduciary duty because it wasn’t “financial planning”. Although the fiduciary duty is still not defined by merely being a CFP or holding out as a CFP certificant, this new and far-broader scope of applying the fiduciary duty when “delivering financial advice” still accomplishes a substantively similar result, as even a focused, single-product recommendation, would still constitute “financial advice” under the new rules.

On the other hand, the CFP Board’s new definition of Financial Advice to which a fiduciary duty applies may actually have gone too far, as the new rules have no actual requirement that the client have agreed to engage the CFP professional in order for the fiduciary standard to occur. By contrast, for the fiduciary duty to apply to an RIA under the Investment Advisers Act, the investment adviser must give investment advice for compensation, and the Department of Labor similarly only applies a fiduciary duty to investment advice given to a retirement investor for compensation. The “compensation” requirement helps to ensure that free advice is not subject to a fiduciary duty, and also helps to ensure that suggestions that may be given in the course of soliciting a prospect are not deemed as fiduciary financial advice even if the advisor is never hired. The CFP Board may need to consider adding a similar stipulation to their current rules, to make it clear that the CFP professional’s obligation to deliver fiduciary financial advice only applies if the client ultimately actually engages the professional for advice for which at least some type of compensation is paid!

New Fiduciary Duties Of A CFP Professional

Of course, if CFP certificants are going to be held to a fiduciary duty, it’s still necessary to define exactly what that means. Most financial advisors, thanks to the recent discussions about the Department of Labor’s fiduciary rule, are familiar with the classic requirement that fiduciaries must act in the best interests of their clients, but in reality a fiduciary duty can (and should be) broader than just this Duty of Loyalty to the client.

In its new rules, the CFP Board defines the obligations of the CFP professional as a fiduciary to include:

CFP Professional’s Fiduciary Duty

A) Duty of Loyalty. A CFP® professional must:

- Place the interests of the Client above the interests of the CFP® professional and the CFP® Professional’s Firm;

- Seek to avoid Conflicts of Interest, or fully disclose Material Conflicts of Interest to the Client, obtain the Client’s informed consent, and properly manage the conflict; and

- Act without regard to the financial or other interests of the CFP® professional, the CFP® Professional’s Firm, or any individual or entity other than the Client, which means that a CFP® professional acting under a Conflict of Interest continues to have a duty to act in the best interest of the Client and place the Client’s interest above the CFP® professional’s.

B) Duty of Care. A CFP® professional must act with the care, skill, prudence, and diligence that a prudent professional would exercise in light of the Client’s goals, risk tolerance, objectives, and financial and personal circumstances.

C) Duty to Follow Client Instructions. A CFP® professional must comply with all objectives, policies, restrictions, and other terms of the Engagement and all reasonable and lawful directions of the Client.

In other words, the CFP Board is, in fact, applying the two core duties of a fiduciary standard: the Duty of Loyalty (to act in the interests of the client), and the Duty of Care (to act with the care, skill, prudence, and diligence of a professional). In addition, the CFP Board still affirms that a CFP professional must follow their clients’ instructions as well. (Which means a CFP professional still has an obligation to follow the clients’ instructions if the client wants to make their own bad financial decision against the advisor’s advice!)

Notably, in the past, the CFP Board’s existing Rules of Conduct for CFP professionals also stated that the CFP certificant – when acting as a fiduciary while providing financial planning or material elements of financial planning – owes to the client a duty of care, and must place the interest of the client ahead of his/her own. However, the new rules go much further in clearly and concretely defining the fiduciary duties of loyalty and care.

Managing Fiduciary Conflicts Of Interest As A CFP Professional

One of the core issues of a fiduciary duty, and the obligation to place the interests of the client above that of the advisor or his/her firm, is how to handle the inevitable conflicts of interest that may arise.

The CFP Board’s new Duty of Loyalty specifically requires that CFP professionals seek to avoid conflicts of interest, or fully disclose any Material conflicts of interest (where “material” is defined as “information that a reasonable client would have considered important in making a decision”).

In addition, a further expansion of the CFP professional’s duties with respect to conflicts of interest, in Section 9 of the new Standards, would obligate the CFP professional to obtain “informed consent” after disclosing any Material conflicts of interest (though informed consent can be handled in conversation in a prospect/client meeting, as written consent is not required).

Furthermore, CFP professionals are expected to “adopt and follow business practices reasonably designed to prevent Material Conflicts of Interest from compromising the CFP professional’s ability to act in the Client’s best interests.” Notably, this is very similar to the “policies and procedures” requirement that the Department of Labor imposes on Financial Institutions engaging in fiduciary advice with respect to retirement accounts – although the DoL fiduciary rule requires the firm to adopt policies and procedures, while the CFP Board’s standards require the individual CFP certificant to adopt those business practices (recognizing that the CFP Board has no jurisdiction over firms, only certificants, and that CFP certificants must comply even if their firms, which may have non-CFPs as well, do not adopt firm-wide policies and procedures).

On the other hand, organizations like the Institute for the Fiduciary Standard have already pointed out that the CFP Board has a history of encouraging CFP professionals to disclose conflicts of interest, but not necessarily urging them to actually avoid or eliminate those conflicts. By contrast, the Department of Labor’s recent fiduciary rule goes into far greater depth about what constitutes an unacceptable (i.e., not realistically manageable) conflict of interest, and outright bans many (as does ERISA’s fiduciary duty). For the CFP Board, though, the new standards have little guidance on whether CFP professionals are actually expected to avoid any conflicts of interest at all, as the focus of the new standards is simply on disclosing material conflicts of interest (and gaining “informed consent” from the client).

In fact, because the CFP Board allows for material conflicts of interest – as long as there is informed consent – there is arguably no requirement that CFP professionals actually avoid any conflict of interest at all, nor necessarily even manage them. After all, while the new rules do suggest that CFP professionals should adopt business practices to prevent material conflicts of interest from compromising their duty of loyalty, the rules also fully permit those material conflicts of interest anyway, as long as the CFP professional can demonstrate that it was disclosed and that the client agreed to the recommendation anyway (i.e., gave informed consent).

Doing Financial Planning And The CFP Board Practice Standards

In addition to the new rules placing on CFP professionals an obligation to act as fiduciaries to clients, including both a Duty of Loyalty and a Duty of Care, the new Practice Standards further emphasize that when providing financial advice, the CFP professional is expected to actually do the financial planning process.

In fact, the new Practice Standards presume that whenever a CFP professional provides financial advice, there should be a financial planning process that integrates together the relevant elements of the Client’s personal and/or financial circumstances to make a recommendation. Or viewed another way… not only are CFP professionals no longer allowed to escape fiduciary duty by providing narrow product recommendations – in an attempt to avoid providing “financial planning” or “material elements of financial planning” – but under the new rules, any (product or other) recommendation or “suggestion to take or refrain from a particular course of action” is presumed to be “financial planning” and necessitates following the full financial planning process, unless the CFP professional can prove that it wasn’t necessary to do so (or that the client refused the comprehensive advice, or limited the scope of engagement to make comprehensive advice unnecessary).

However, it’s important to recognize that “doing” financial planning when giving financial advice still doesn’t necessarily mean every client must be provided a comprehensive financial plan. Under the new conduct standards, “financial planning” itself is defined as:

“Financial Planning: A collaborative process that helps maximize a Client’s potential for meeting life goals through Financial Advice that integrates relevant elements of the Client’s personal and financial circumstances.”

The key term here is “relevant elements” of the client’s personal and financial circumstances. Thus, just as a doctor doesn’t need to conduct a full-body physical exam with blood analysis just to set a broken arm, neither would a CFP professional be required to do a comprehensive financial plan just to help a client set up a 529 college savings plan. Nonetheless, a full evaluation of the relevant circumstances – from the ages of children and time horizon to college, to the risk tolerance of the parents, their tax situation, and available savings and other resources for college – would still be necessary to deliver appropriate financial (planning) advice.

EGADIM 6-Step Process Becomes A 7-Step Financial Planning Process

Perhaps more notable, though, is that the financial planning process itself is changed and updated under the new conduct standards.

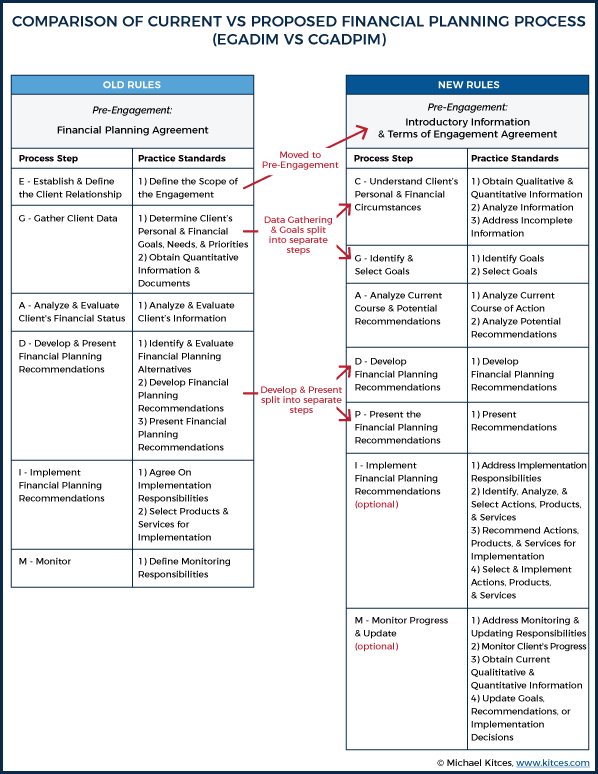

In the past, the standard financial planning process was known by the acronym EGADIM: Establish client/planner relationship, Gather data, Analyze the client situation, Develop plan recommendations, Implement the plan, and Monitor the plan. And each of those parts of the 6-step process had 1-3 levels of detailed practice standards about how they should be delivered.

Now, under the new rules, financial planning will entail a 7-step process of:

1) Understand the Client’s Personal and Financial Circumstances (including gathering quantitative and qualitative information, analyzing the information, and identifying any pertinent gaps in the information);

2) Identify and Select Goals (including a discussion on how the selection of one goal may impact other goals)

3) Analyze the Current Course of Action and Potential Recommendations (evaluating based the advantages and disadvantages of the current course of action, and the advantages and disadvantages of potential recommendations)

4) Develop Financial Planning Recommendations (including not only what the client should do, but the timing and priority of recommendations, and whether recommendations are independent or must be implemented jointly)

5) Present Financial Planning Recommendations (and discuss how those recommendations were determined)

6) Implement Recommendations (including which products or services will be used, and who has the responsibility to implement)

7) Monitoring Progress and Updating (including clarifying the scope of the engagement, and which actions, products, or services, will be the CFP professionals’ responsibility to monitor and provide subsequent recommendations)

Unfortunately, the new 7-step process isn’t as conducive to an acronym as EGADIM was, though a new option might be CGADPIM (Circumstances, Goals, Analyze, Develop, Present, Implement, Monitor). In practice, the primary difference under the new rules is that the prior requirement to “establish the scope of the engagement” is not considered part of the financial planning process itself (though it will still be separately required, as discussed below), the “gather client data” phase is now broken out into two standalone steps of the process (first to gather information about the client’s Circumstances, then to identify the client’s Goals), and the CFP Board has similarly separated the prior “Develop and Present Recommendations” of EGADIM into separate “Develop” and “Present” process steps.

Another key distinction of the new 7-step process, though, is that the last two steps – to Implement, and to Monitor – are explicitly defined as optional, and are only an obligation for the CFP professional if the client’s Scope of Engagement specifically dictates that the CFP professional will be responsible for implementation and/or monitoring (although notably, the presumption is that the CFP professional will have such responsibilities, unless they are specifically excluded in the Scope of Engagement).

In other words, if the CFP professional defines the scope of the agreement as only leading up to presenting recommendations (the CGADP part of the new financial planning process), but leaves it up to the client to proceed with implementation and monitoring, that is permitted under the new rules… recognizing that some clients prefer to only engage in more “modular” advice and a “second opinion” from a CFP professional, but may not wish to implement with that CFP professional.

Introductory Information And Financial Planning Terms (And Scope) Of Engagement

Currently, the CFP Board’s Rules of Conduct when a CFP Professional is engaged by a client to provide financial planning (or material elements of financial planning) include an obligation to provide information to clients (prior to entering into an agreement), including the responsibilities of each party, the compensation that the CFP professional (or any legal affiliates) will or could receive, and, upon being formally engaged by the client for services, the CFP professional was/is expected to enter into a formal written agreement, specifying the (financial planning) services to be provided.

Under the new rules, these disclosure and engagement requirements would be expanded further, into a series of (at least) two written documents: the first is “Introductory Information” to be provided to a prospect (before becoming a client), and the second is a “Terms of Engagement” agreement provided to a client (at the time the client engages the advisor).

The Introductory Information must include:

Introductory Information

1) Description of the CFP professional’s available services and category of financial products;

2) Description of how the client pays, and how the CFP Professional and the Professional’s Firm are compensated for providing services and products;

3) Brief summary of any of the following Conflicts of Interest (if applicable): offering proprietary products; receipt of third-party payments for recommending products; material limitations on the universe of available products; and the receipt of additional compensation when the Client increases the amounts of assets under management; and

4) A link to (or URL for) relevant webpages of any government authorities, SROs, or professional organizations, where the CFP professional’s public disciplinary history or personal/business bankruptcies are displayed (e.g., the SEC’s IAPD, FINRA BrokerCheck, and the CFP Board’s own website).

The new rules state that for RIAs, the delivering of Form ADV Part 2 will satisfy the Introductory Information requirement. Broker-dealers, though, would need to create and distribute their own Introductory Information guidance. (The CFP Board has indicated that it will be creating an Introductory Information template for advisors and brokers to use.) The Introductory Information is expected to be delivered to a prospect at the time of initial consultation, or “as soon as practicable thereafter”, and it may be delivered in writing, electronically, or orally (if appropriate given a [presumably limited] scope of services).

In addition, when a CFP professional is actually engaged to give financial advice, the CFP professional must further provide a written Terms of Engagement agreement, including:

Terms Of Engagement Financial Planning Agreement

- Scope of Engagement (and any limitations), period for which services will be provided, and client responsibilities

- Further disclosures, to the extent not already provided, including:

- More detailed description of costs to the client, including:

- How the client pays, and how the CFP Professional and the Professional’s Firm are compensated for providing services and products;

- Additional types of costs that the Client may incur, including product management fees,

- Identification of any Related Party that will receive compensation for providing services or offering products

- Full disclosure of all Material Conflicts of Interest

- Link to relevant webpages of any government authorities, SROs, or professional organizations, where the CFP professional’s public disciplinary history or personal/business bankruptcies are displayed

- Any other information that would be Material to the client’s decision to engage (or continue to engage) the CFP professional or his/her firm

As mentioned earlier, the CFP Board’s current Standards of Professional Conduct already require that CFP certificants enter into a written agreement with clients that defines the scope of the engagement. But with an expanded fiduciary duty for CFP professionals, it seems likely that financial advisors may become more proactive about clearly defining the scope of what they will, and won’t, do as a part of the client engagement. Especially since the CFP Board’s new 7-step process makes it optional for the CFP to follow through on the implementation and/or monitoring phases of the process, but only if the scope of engagement explicitly excludes those steps of the process.

In addition, the mere delivery of a “comprehensive” financial plan, under a more “comprehensive” fiduciary duty, creates potential new liability exposures for financial advisors. If the advisor’s agreement says the financial plan is “comprehensive”, what, exactly, does that cover? Is it everything in the CFP Board’s current topic list? Does that mean CFP professionals could get themselves into trouble for offering a “comprehensive” financial plan, but failing to review a will or a trust, or an automobile or renter’s insurance policy? Under the new standard in the future, CFP professionals may want to become far more proactive about stating exactly what they will cover in a plan – to more concretely define the scope of engagement – rather than just stating that it will be “comprehensive”.

The new standards of conduct also require that the CFP professional disclose to the client any Material change of information that occurs between the Introductory Information and when the actual Terms of Engagement are signed, along with any Material changes that occur after the engagement begins but during the scope of the (ongoing) engagement. Ongoing updates must be provided at least annually, except for public disciplinary actions or bankruptcy information, which must be disclosed to the client within 90 days (along with a link to the relevant regulatory disclosure websites).

Cleaning Up Fee-Only Definitions And Sales-Related Compensation

One of the most challenging issues for the CFP Board in recent years has been its “compensation definitions” – specifically pertaining to when and how a CFP professional can call themselves “fee-only”, which had led to both a lawsuit against the CFP Board by Jeff and Kim Camarda, the resignation of (now-former) CFP Board chair Alan Goldfarb (who was later publicly admonished), and a series of ongoing debacles for the CFP Board as it kept trying to update its flawed interpretation of the original “fee-only” compensation definition.

The problem was that under the prior rules, “fee-only” was defined as occurring “if, and only if, all of the certificant’s compensation from all of his or her client work comes exclusively from the clients in the form of fixed, flat, hourly, percentage, or performance-based fees.” And the certificant’s “compensation” was in turn defined as “any non-trivial economic benefit, whether monetary or non-monetary, that a certificant or related party receives or is entitled to receive for providing professional activities.”

The primary problem in this context was that the CFP Board interpreted these rules to mean that if a related party could receive non-fee compensation, the CFP certificant couldn’t call themselves “fee-only”, even if the CFP professional could prove that 100% of their clients paid 100% in fees (and no commissions) for any/all client work. In other words, the CFP Board imputed the possibility of a commission to taint the CFP professional’s status as fee-only, regardless of whether the client ever actually paid a commission to anyone, ever. Such that even being able to prove that all your clients only paid fees wasn’t a legitimate defense to claiming that you were fee-only!

Under the new Standards of Conduct, the overall structure of “fee-only” is substantively similar, but updated in ways that should help to resolve many of the prior problems and misinterpretations of the definition. Now, fee-only is defined as:

Fee-Only. A CFP professional may represent his or her compensation method as “fee-only” only if:

- The CFP professional and the Professional’s Firm receive no Sales-Related Compensation; and

- Related Parties receive no Sales-Related Compensation in connection with any Professional Services the CFP professional or the CFP Professional’s Firm provides to Clients.

In turn, “Sales-Related Compensation” is defined as:

Sales-Related Compensation. Sales-Related Compensation is more than a de minimis economic benefit for purchasing, holding for purposes other than providing Financial Advice, or selling a Client’s Financial Assets, or for the referral of a Client to any person or entity. Sales-Related Compensation includes, for example, commissions, trailing commissions, 12(b)1 fees, spreads, charges, revenue sharing, referral fees, or similar consideration.

Sales-Related Compensation does not include:

- Soft dollars (any research or other benefits received in connection with Client brokerage that qualifies for the “safe harbor” of Section 28(e) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934);

- Reasonable and customary fees for custodial or similar administrative services if the fee or amount of the fee is not determined based on the amount or value of Client transactions; or

- The receipt by a Related Party solicitor of a fee for soliciting clients for the CFP® professional or the CFP® Professional’s Firm.

Not surprisingly, “sales-related compensation” is defined as any type of compensation that is paid for any type of purchase or sale related to a client’s financial assets, or for a referral (that might subsequently lead to such outcomes). Thus, for instance, selling an investment or insurance product for a commission would be sales-related compensation, as would referring a client to an insurance agent or broker (or anyone else) who pays the CFP professional for referring the lead. Although under the current rules, using an outsourced investment provider – i.e., a TAMP – might also be deemed a “referral” fee, to the extent that many TAMPs collect the AUM fees and then remit a portion of the CFP professional as a solicitor/referrer fee, which would no longer be allowed, even if the cost is the same to the client as the CFP professional who hires his/her own internal CFA to run the portfolio. Will the CFP Board be compelled to refine its “sales-related compensation” rules to allow for level AUM fees as a part of standard solicitor agreements?

More generally, though, it’s notable that the new “fee-only” rules are not actually defined by whether the CFP professional receives various types of AUM, hourly, or retainer fees; instead, it is defined by not receiving any type of Sales-Related Compensation (such that client fees are all that is left). As a result, the new “fee-only” definition might more aptly be explained as being a “no-commission” (and no-referral-fee) advisor instead.

A key distinction of the new rules, though, is that for a CFP professional to be fee-only, neither the CFP professional nor his/her firm can receive any sales-related compensation, but a related party can receive sales-related compensation as long as it is not “in connection with” the services being provided to the client by the CFP professional or his/her firm. This shift is important, as otherwise, any connection between the CFP professional and any related party to his/her firm could run afoul of the fee-only rules; for instance, if a fee-only RIA was bought by a bank or holding company, which separately had another division that happened to offer mortgages (for a commission), the RIA would lose its fee-only status, even if no clients ever actually did business with the related subsidiary. Under the new rules, external related parties could still co-exist in a manner that doesn’t eliminate the CFP professional’s fee-only status, as long as no clients actually do business with that related party (so no clients ever actually pay a commission to a related party), and the CFP professional’s own firm doesn’t directly accept any type of sales-related compensation.

Notably, under these new definitions, Jeff and Kim Camarda – who had a “fee-only” RIA but referred clients internally to a co-owned insurance subsidiary that earned commissions – would still not have been permitted to call themselves “fee-only” (as clients really were paying commissions to a related party in connection with the Camardas’ financial advice). However, the strange case of former CFP Board chair Alan Goldfarb, who was deemed to violate the fee-only rules because his RIA-parent-company accounting firm also owned a broker-dealer even though it was never stated that a single client of Goldfarb’s ever actually paid a commission to that entity, would have been (appropriately) still allowed to call himself “fee-only”.

On the other hand, it’s not entirely clear whether the CFP Board considered how CFP professionals might shift towards fee-only compensation in the future. For instance, what happens if a CFP professional who currently earns commissions and trails decides to stop doing any commission-based business, and operate solely on a fee-only basis in the future… but doesn’t want to walk away from his/her existing trails for prior business? Under a strict interpretation of the current “sales-related compensation” rules, even old sales-related compensation that has no relationship to current clients would still run afoul of the rules, even though the CFP professional really does work solely on a fee-only basis now. In addition, receiving “old” trails typically still requires the CFP professional to maintain a broker-dealer registration (to remain as Broker of Record), and/or a state Insurance license (and appointment to one or several insurance companies) to remain Agent of Record… which means the CFP professional would still be affiliated with a firm that receives sales-related compensation (which also runs afoul of the rules). Does the CFP Board need to add a further clause that clarifies how CFP professionals who are transitioning to fee-only can keep old commission trails for prior sales, and “old” affiliations to broker-dealers or insurance companies to receive those trails, and still be permitted to hold out as fee-only going forward, as long as no new clients will ever again compensate the advisor via commissions or other sales-related compensation?

CFP Board Cautions Against Marketing “Fee-Based” Compensation

In addition to tightening the CFP Board’s compensation of “fee-only”, the new rules also explicitly caution CFP professionals against the use of the term “fee-based”, which was originally a label for investment wrap accounts where trading costs were “fee-based” rather than a per-trade commission, but in recent years has occasionally been used by brokers to imply they are offering “fee-only” advice (relying on consumers to not understand the difference between fee-based and fee-only).

To limit this, the new CFP Board conduct standards would require that anyone who holds out as “fee-based” to clearly state that the CFP professional either “earns fees and commissions”, or that “the CFP professional is not fee-only”, and that the term should not otherwise be used in a manner that suggests the CFP professional is fee-only. (Recognizing that the term is enshrined in SEC regulations as a part of fee-based wrap accounts, and can’t realistically be eliminated from the investment lexicon altogether.)

The caveat, however, is that while the CFP Board is explicitly cracking down on the use of “fee-based” as a marketing label, the organization is backing away from its prior “Notice to CFP Professionals” guidance from 2013, which grouped all financial advisor compensation into being either “fee-only”, “commission-only”, or “commission and fee”. Which seems concerning, as while grouping CFP professionals into “just” three buckets has limited value – when most are in the middle and operate with some blend of commissions and fees – it’s still better than not requiring consistent definitions at all. Otherwise, what’s to stop CFP professionals from just coming up with another label for being (partially) fee-compensated, that isn’t fee-only, but sounds similar… which is precisely why “fee-based” has been increasingly adopted in recent years anyway.

In other words, if the CFP Board states: “All CFP professionals must disclose that their compensation is fee-only, commission-and-fee, or commission-only, and should provide further compensation disclosure details as appropriate” then at least CFP professionals will disclose their compensation consistently. But with the CFP Board’s current approach, a CFP professional who receives at least some fees might have to stop using “fee-based”, but could just use similar words like “fee-oriented” or “fee-compensated” or “fee-for-service” financial advice, which would still focus on and imply fees (and fee-only) without stating that the actual compensation includes commissions as well (as using the term “fee and commission” is now only required when attached to fee-based).

Enforcement Of The New CFP Board Standards Of Conduct?

Notwithstanding its expansion in the scope of fiduciary duties that would apply to CFP professionals, it’s important to recognize that the CFP Board’s ability to enforce its standards is still somewhat limited.

At most, the CFP Board’s Disciplinary and Ethics Commission (DEC) can only privately censure or publicly admonish a CFP certificant, and/or in more extreme cases to suspend or revoke the CFP marks from that individual. However, that doesn’t mean the CFP Board can actually limit someone’s ability to be a practicing financial advisor, who offers (and is paid for giving) financial advice to the public. Nor can the organization fine or otherwise financially punish a CFP certificant, beyond the financial consequences that might occur to the CFP certificant’s business if he/she is either publicly admonished, or has his/her marks suspended or revoked (which is also part of the public record).

Although the real challenge for the CFP Board is that because it is not an actual government-sanctioned regulator, its ability to collect the information necessary to adjudicate its disciplinary hearings is a significant challenge. Because broker-dealers and advisory firms have in some cases refused to provide the necessary information to the CFP Board regarding a CFP certificant and his/her clients when a client is filed, as the firm fears that actual government regulators (e.g., the SEC and/or FINRA) might discipline them for a breach of client privacy by sharing information with the CFP Board in the first place! In fact, back in 2011 the CFP Board had to seek out a “No-Action” letter from the SEC to affirm that it was permissible for firms to share “background documents” without violating Reg S-P, and continued pushback from firms led the CFP Board to request a follow-up No-Action letter request in 2014 to further expand the scope of what firms even could share with the CFP Board.

Of course, in situations where a client files a complaint with the CFP Board, the client has authorization to release his/her own information to the CFP Board to evaluate the complaint. But the limitations of the CFP Board’s ability to even investigate complaints against CFP certificants, especially in the case of third-party complaints (i.e., where it is not the client who submits the complaint, and his/her information to document it), raise serious concerns about its ability to effectively enforce its new standards. It’s not a coincidence that the overwhelming majority of current CFP Board disciplinary actions are based almost entirely on public information (from bankruptcy filings and DUI convictions, to CFP certificants who are disciplined after the SEC or FINRA already found them publicly guilty), and/or pertain to situations that wouldn’t require client-specific information anyway (e.g., whether the advisor misrepresented his/her compensation in marketing materials).

In other words, the “good” news of the new CFP Conduct Standards is that CFP professionals will be required to meet a fiduciary standard of care when providing any kind of financial advice to clients… but what happens if they don’t? To what extent can the CFP Board enforce against those who don’t effectively comply with the rules, and then simply refuse to provide information – under the guise of Reg S-P – when a complaint is filed? Will the CFP Board have to rely on consumers to file their own complaints, just to get the information necessary to investigate such complaints? And is the CFP Board prepared to enforce against the non-trivial number of CFP certificants who have been acting as non-fiduciaries for years or decades already by using their CFP marks to sell products (which now will be subject to a fiduciary obligation for the first time)? Especially since the CFP Board doesn’t require CFP professionals to state in writing that they’re fiduciaries to their clients, which means the CFP Board’s fiduciary duty still won’t necessarily be grounds for a client to actually sue the financial advisor for breach of fiduciary duty (as the CFP certificant would simply be failing to adhere to the CFP Board’s requirement that he/she act as a fiduciary, and not an actual fiduciary commitment to the client!).

CFP Board Anonymous Case Histories And Case Law Precedents

On the other hand, one of the greatest challenges for the CFP Board may not be the consequences if it can’t investigate claims against CFP professionals, but what happens if it does see an uptick in the number of complaints and enforcement actions under the new CFP Conduct Standards.

The problem is that ultimately, a large swath of the newly proposed Conduct Standards contain potentially subjective labels to determine whether the rules have actually been followed, or not. For instance, the word “reasonable” or “reasonably” is used a whopping 26 times in the new Conduct Standards, pertaining to everything from whether a conflict of interest in Material (based on whether a “reasonable” client would have considered the information important), to whether a related party is related based on whether a “reasonable” CFP professional would interpret it that way, to requirements that CFP professionals diligently respond to “reasonable” client inquiries, follow all “reasonable” and lawful directions of the client, avoid accepting gifts that “reasonably” could be expected to compromise objectivity, and provide introductory information disclosures to prospects the CFP professional “reasonably” anticipates providing subsequent financial advice to. In addition, the entire application of the rules themselves depend on the CFP Board’s “determination” of whether Financial Advice was provided (which triggers the fiduciary obligation for CFP professionals), and CFP professionals with Material conflicts of interest will or will not be found guilty of violating their fiduciary duty based on the CFP Board’s “determination” of whether the client really gave informed consent or not.

In other words, the CFP Board’s new Standards of Conduct leave a lot of room for the Disciplinary and Ethics Commission (DEC) to make determinations of what is and isn’t reasonable in literally several dozen instances of the rules, as well as determining how they will determine when Financial Advice is given and what does and doesn’t really constitute informed consent.

To be fair, the reality is that it’s always the case that regulators and legislators write the rules, and the courts interpret them in the adjudication process. So the idea that the CFP Board’s DEC will have to make interpretations of all these new rules isn’t unique or that out of the ordinary. And frankly, using “reasonableness” as a standard actually helps to reduce the risk that a CFP professional is found guilty of something that is “reasonably” what another CFP professional would have done in the same situation. “Reasonableness” standards actually are peer-based professional standards, which is what you’d want for the evaluation of a professional.

However, when courts interpret laws and regulations, they do so in a public manner, which allows everyone else to see how the court interpreted the rule, and provides crucial guidance for everyone who follows. Because once the court interprets whether a certain action or approach is or isn’t permitted, it provides a legal precedent that everyone thereafter can rely upon. In point of fact, many of the key rules that apply to RIA fiduciaries today, including the fact that a fiduciary duty applies to RIAs in the first place, didn’t actually come from regulators – it came from how the courts interpreted those regulations (which in the case of an RIA’s fiduciary duty, stemmed from the 1963 Supreme Court case of SEC v Capital Gains Research Bureau).

The problem, though, is that the CFP Board’s disciplinary process is not public. Which means even as the DEC adjudicates 26 instances of “reasonableness”, no one will know what the DEC decided, nor the criteria it used… which means there’s a risk that the DEC won’t even honor its own precedents, and that rulings will be inconsistent, and even if the DEC is internally consistent, CFP professionals won’t know how to apply the rules safely to themselves until they’re already in front of the DEC trying to defend themselves!

Notably, this concern – of the lack of disciplinary precedence in CFP Board DEC hearings – was a concern after the last round of practice standard updates in 2008, and did ultimately lead to the start of the CFP Board releasing “Anonymous Case Histories” in 2010 that provide information on the CFP Board’s prior rulings. (The case histories are anonymous, as making them public, especially in situations where there was not a public letter of admonition or a public suspension or revocation, would itself be a potential breach of the CFP professional’s privacy.)

However, the CFP Board’s current Anonymous Case History (ACH) database is still limited (it’s not all cases, but merely a collection of them that the CFP Board has chosen to share), and the database does not allow CFP professionals (or their legal counsel) any way to do even the most basic keyword searches OF the existing case histories (instead, you have to search via a limiting number of pre-selected keywords, or by certain enumerated practice standards… which, notably, will just be even more confusing in the future, as the current proposal would completely re-work the existing practice standard numbering system!).

Which means if the CFP Board is serious about formulating a more expanded Conduct Standards, including the application of a fiduciary duty and a few dozen instances of “reasonableness” to determine whether the CFP professional met that duty, the CFP Board absolutely must expand its Anonymous Case Histories database to include a full listing of all cases (after all, we don’t always know what will turn out to be an important precedent until after the fact!), made available in a manner that is fully indexed and able to be fully searched (not just using a small subset of pre-selected keywords and search criteria). Especially since, with the CFP Board’s unilateral update to its Terms and Conditions of Certification last year, CFP professionals cannot even take the CFP Board to court if they dispute the organization’s findings, and instead are bound to mandatory arbitration (which itself is also non-public!).

Overall Implications Of The CFP Board’s New Fiduciary Standard

Overall, for CFP certificants (including yours truly) who have called for years for the CFP Board to lift its fiduciary standard for its professionals, there’s a lot to be liked in the newly proposed Standards of Conduct. The CFP Board literally leads off the standards with the application of the fiduciary duty to CFP professionals (it’s the first section of the new Standards of Conduct!), and expands the scope of the CFP Board’s standards to cover not just delivering financial planning or material elements of financial planning, but any advice by a CFP professional (for which it is presumed that delivering that advice should entail doing financial planning!).

In addition, the CFP Board has made a substantial step forward on its disclosure requirements for conflicts of interest, particularly regarding the creation of its “Introductory Information” requirement for upfront disclosures to prospects, and its expanded and more detailed requirements for setting the Terms of Engagement for client agreements. (For anyone who still believes the CFP Board is beholden to its large-firm broker-dealers, this should definitively settle the issue – as broker-dealers compliance departments will most definitely not be happy that the CFP Board as a “non-regulator” is imposing disclosure requirements on their CFP brokers! In fact, there’s a non-trivial risk for the CFP Board that some large brokerage or insurance firms may decide to back away from the CFP Board’s expansion of its fiduciary duty, just as State Farm did back in 2009 when the CFP Board first introduced its fiduciary standard.)

On the other hand, it is still notable that despite increasing the disclosure requirements associated with its expanded fiduciary duty for CFP professionals, the CFP Board isn’t actually requiring CFP professionals to change very much from what they do today. Material conflicts of interest must be disclosed, but obtaining informed consent appears to be a legitimate resolution to any actual conflict of interest. And debating whether a conflicted recommendation that the client agreed to with informed consent was still a fiduciary breach or not would quickly come back to a determination of whether the CFP professional’s advice met various standards of “reasonableness” – which, as of now, aren’t entirely clear standards, and if the CFP Board can’t effectively expand its Anonymous Case Histories, may not get much clearer in the future even as the DEC interprets what is “reasonable”, either.

In the meantime, though, to the extent that the CFP Board’s newly expanded fiduciary standard – both the duty of loyalty, and the expanded duty of care – does create at least some new level of accountability for CFP professionals, the real challenge may be the CFP Board’s own ability to enforce and even investigate complaints if and when they do occur. As the saying goes, the CFP Board needs to make sure its mouth isn’t writing checks that its body can’t cash, by promulgating standards of conduct it may struggle to effectively enforce. Whether and how the CFP Board will expand and reinvest into its own disciplinary process and capabilities remains to be seen.

But overall, the CFP Board’s newly proposed Standards of Conduct really do appear to be a good faith effort to step up and improve upon the gaps of the prior/existing standards of professional conduct. The scope of what constitutes “doing” financial planning for the purposes of the fiduciary duty is expanded (and if anything, the CFP Board may have gone too far by not limiting the scope of fiduciary duty to an established financial advice relationship for compensation), the fee-only compensation definition is improved (although the CFP Board may be starting a problematic game of whack-a-mole by just punishing “fee-based” instead of more formally establishing a standardized series of compensation definitions), and although the CFP Board didn’t crack down on material conflicts of interest to the extent of the Department of Labor’s fiduciary rule, it did still move the ball further down the field by more fully highlighting prospective conflicts and increasing the disclosure requirements for both RIAs and especially broker-dealers and insurance firms.

For the time being, though, it’s also important to recognize that these are only proposed standards, and not final. The CFP Board is engaging in a series of eight Public Forums in late July across the country to gather feedback directly from CFP professionals (register for one in your area directly on their website here), and is accepting public comment periods for a 60-day period (ending August 21st), which you can submit either through the CFP Board website here, or by emailing [email protected]. Comments and public forum feedback will then be used to re-issue a final version of the standards of conduct (or even re-proposed if the Commission on Standards deems it necessary to have another round of feedback) later this year.

And for those who want to read through a fully annotated version of the proposed Standards of Conduct themselves, the CFP Board has made a version available on their website here.

So what do you think? Does this represent a positive step forward for the CFP Board and its Standards of Conduct for CFP professionals? Did the CFP Board go far enough in trying to move the standards forward? Or too far at once? Do you think the CFP Board will be able to effectively enforce the new standards? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!