Home ownership has long been viewed as a foundation of building wealth. For many Americans, the equity in their home is the single greatest asset on their balance sheet, often dwarfing the amount of investment assets they hold in savings and retirement accounts. But does that really mean that home ownership is the best long-term investment around, and a step that everyone should take if they wish to build financial success in the future? Not necessarily. Because in reality, the real reason home ownership is the average American's greatest asset is not because of appreciation in the value of housing; it's simply because of leverage. Read More...

As prices of almost everything on the grocery store shelves seems to creep higher, we seem to get a bigger buzz than ever by saving money in the checkout line. Coupon use is on the rise, and this week was the series premier of TLC's "Extreme Couponing" television show.

Yet while it's nice to save a little money when you reach the cash register, and every bit of savings helps a little bit in the long run, let's keep it all in perspective: clipping coupons, a little or even a lot, is not the key to a comfortable retirement. When we talk about the importance of saving for long-term wealth accumulation, it's about the savings that you invest, not the discounts at the cash register. The road to long-term financial success is not paved with coupons!Read More...

Although we may focus on various steps we can take to get a better return on our investments or a lower cost for our debt, in reality the most foundational base for financial success is having good financial habits.

Yet in practice - as we've all witnessed with clients - not everyone has already learned and embraced good financial habits, and even worse, it can be extremely difficult to change bad financial habits. On the other hand, the weight loss field is in a very similar position; just as the key to financial success is to save more and spend less (than you make), the key to weight loss is to exercise more and eat less.

So if it's once again all about habits, maybe there's something that planners can learn about helping clients with financial habits from weight loss experts who assist with other types of behavior and habit change.

A core aspect of the financial planning process for many planners is not just the analysis and development of recommendations for clients, but the embodiment of that work into a written financial plan document. In the plan presentation meeting itself, some planners use this written document as a guide to walk the client through the analysis and recommendations, although many simply focus on key recommendations and points for the client to understand, and let the clients simply take the written document with them.

Yet once the clients leave the office, written financial plan in hand, how many of them ever crack the spine open and take a look at it sitting at home? Anecdotally, it seems to me that most planners agree on the answer to that question: virtually no one ever opens up their financial plan document at any point after they walk out of the planner's office.

Which begs the question: if "no one" ever reads the written comprehensive financial plan that's being delivered, why do we keep producing them?

For most financial planners, the focus of college planning advice is accumulation based. After all, it seems that almost by definition, "planning" for college means acting in advance by saving up money ahead of time so that the costs can be funded when the child is ready to matriculate. If you just pay as you go when the tuition bills show up, you may be funding college, but that doesn't really constitute "planning" does it? Yet the reality is that many actions can be taken in the final high school years leading up to college beyond just long-term accumulation planning; however, most planners seem to skip these client conversations about so-called "late stage college funding planning" opportunities, despite the potential for a high impact on the actual client costs to fund college. For the most part, it seems this is by no means willful negligence, but simply a lack of awareness about the strategies that really do exist. We've just never had much opportunity for training about how to do this effectively. Until now.

Although so many financial and economic models take as a fundamental assumption the idea that we are all rational human beings, the emerging research from the field of behavioral finance clearly illustrates this is a false assumption. In reality, we have some pretty strange financial behaviors, that do not appear to be at all consistent with a purely rational decision-making process. Fortunately, the world of behavioral finance is showing us that at least some of our irrational behavior occurs in a consistent manner that we can predict, so while our actions may not be rational at least they can be anticipated. But that in turn begs a fundamental question: when faced with a client making an irrational financial decision, is the rational (for the planner) solution to try to change the client to be more rational as well, or to change the recommendation to fit the client's irrational behavior? Read More...

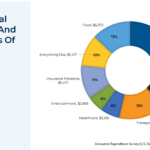

Almost by definition for many, the essence of financial planning is that it's comprehensive. Financial planners don't just look at a particular problem or product; they account for everything holistically to arrive at a recommendation and solution that fits in with the big picture. In other words, they don't just plan for a slice of the pie; they plan for the whole pie. Yet it seems that for many planners, the "whole pie" is the client's balance sheet; we plan for all the different assets (and liabilities?) that the client has, not just a particular account. What about the OTHER pie, though? Not the asset one; the INCOME pie.Read More...

As financial planners, we have a responsibility to give people the best advice to guide them towards achieving their goals. In most cases, it's very straightforward to develop these recommendations, by applying the technical rules and looking at "the numbers" to calculate what path/route/option is best. Yet ultimately, the solutions don't count unless they're implemented correctly, and if you want to take that next step, you have to deal with real world behaviors. Which leads to a fundamental problem: what happens if the "best" solution is one that's not conducive to human behavior? How do you navigate the intersection between behavior and the numbers? How do you develop rational financial planning recommendations in a world where people don't always behave rationally?Read More...

It is a common financial planning challenge: just how much time and effort should be spent trying to make the numbers in your financial planning projections as precise as possible? How much research should you put into refining the growth rate assumption for each asset in the portfolio? And its volatility? And its correlation? What about client spending? Should we build a detailed cash flow for retirement, year by year, or is it sufficient to just provide a rough guesstimate of how much money will go towards retirement outflows? Many planners have a strong tendency to fine-tune these numbers and make them as precise as possible, but that in turn begs the question... in a world where the future itself is so uncertain, are the results really more accurate, or is an effort for greater precision just an exercise in futility?

The personal finance space has no shortage of tips to managing your spending, from bag lunches in lieu of eating out at work to home-brewed coffee instead of the morning Starbucks routine. Yet the reality seems to be that in so many situations, we dig ourselves a tremendous spending hole because of our big purchases, and then worry tremendously about the small stuff trying to make up the difference. If you really want to change your financial reality for the better, though, it's the big stuff you really need to focus on - where you live, and what you drive.