Executive Summary

While portfolio management understandably focuses on how best to allocate a portfolio, the reality for many (or even most) investors is that their financial assets may not even be the majority of their total net worth, compared to other assets like real estate, the (illiquid) value of their pensions and Social Security, and for those who haven’t retired yet, their human capital. In fact, for younger workers, their human capital – or the present value of their future earnings from employment – may actually be the largest asset they own!

Yet the reality is that assets like human capital, illiquid pensions and Social Security, and even real estate (especially if in the form of a primary residence) are not easily traded or altered; in other words, whatever you’ve got, and the risk it entails, is largely what you’re stuck with. In turn, this suggests that if the individual is going to try to optimize the risk and return of their total net worth – across all these different “asset classes” – that the portfolio is the one that should change to accommodate the rest, because it is the most malleable.

And in fact, recent research from Morningstar suggests that, when viewed on this basis, the optimal portfolio allocations for many investors really do shift, potentially quite significantly! Human capital, in particular, plays a significant role, given that both the growth rate potential and the volatility risk can vary quite a bit from one industry to the next, and different industries themselves have varying correlations to different segments of the market and (financial) asset classes. Which means, in the end, that advisors who are not considering these other balance sheet risks – especially for the human capital of their working clients – may be significantly over- or under-risking the client’s total household balance sheet over time!

Viewing an Investor’s Total Household Wealth – No Portfolio Is An Island

Reducing portfolio volatility through diversification is a fundamental tenet of asset allocation and portfolio design. Yet a recent paper from Morningstar’s David Blanchett and Philip Straehl, entitled “No Portfolio Is An Island”, makes the case that applying such a technique must go beyond just the portfolio itself, and look at a household’s total wealth. Especially given the reality that for much of our lives, our portfolio – or more generally, “financial wealth” – may not even be the biggest asset on our balance sheet!

For instance, imagine for a moment that we have a 25-year-old client who earns $40,000/year (after tax). As long as that client is capable of working, his/her “human capital” is basically an asset that will pay a “dividend”, in the form of earnings from employment, every year the client continues to work. And while we can’t directly price the value of the human capital asset, the fact that it pays an ongoing implied dividend means we can estimate its value using a relatively basic dividend discount model, where w is wages, r is the discount rate, and g is the growth rate (in wages):

Human Capital = w / (r – g)

If this 25-year-old client can save a portion of income, eventually he/she will begin to accumulate some financial capital. In the meantime, the client may also buy a house (i.e., make a real estate investment), and along the way will begin to accumulate Social Security payments as well (a form of “pension” wealth most workers still generate, even with the overall decline in traditional corporate pensions!).

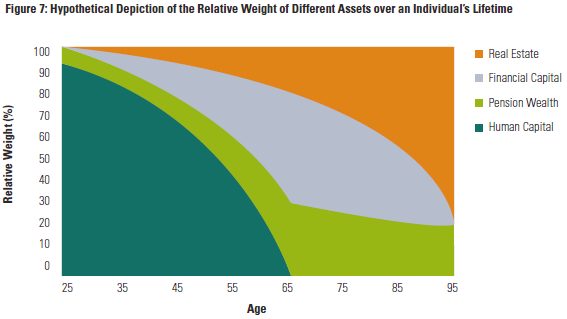

Over time, the value of human capital will decline, the value of financial and pension wealth will rise and fall (as it is accumulated for retirement and then spent down in retirement), and the value of real estate will simply continue to compound (assuming its value is not spent in retirement). In fact, over the cumulative lifetime with some relatively straightforward assumptions, the client’s relative weight of these different groupings – real estate, financial capital, pension wealth, and human capital – will vary quite significantly, as shown below (from the Morningstar research paper):

Source: "No Portfolio Is An Island" by Blanchett & Straehl

As the graphic reveals, even at its peak – the date the individual retires – financial wealth is barely more than half the client’s total net worth! To say the least, this implies that providing an asset allocation of financial assets, and ignoring the rest, could result in a significant misallocation of assets, especially during the working years when the client’s human capital is actually more than half the net worth all the way until his/her early 50s (and remains over 80% of net worth until the client turns 40!).

And since the portfolio is far more easily adjusted than other assets, the reality is that if the client wants to manage his/her total household wealth and risk/return profile, the best way to do it is to adjust the financial portfolio around the rest of the assets!

Adjusting Portfolios For Human Capital And Other Factors

To further analyze the relationship between human capital and financial assets in particular, Blanchett and Straehl looked at how human capital has varied over time for workers in specific industries. Using a somewhat more sophisticated mortality-adjusted version of the aforementioned valuation model for human capital (from “Human Capital, Asset Allocation, and life Insurance” by Ibbotson, Chen, Milevsky, and Zhu), the authors calculated an individual’s human capital over the years by applying the industry-specific corporate bond rates as the discount rate, and the industry-specific wage increases as the growth rate.

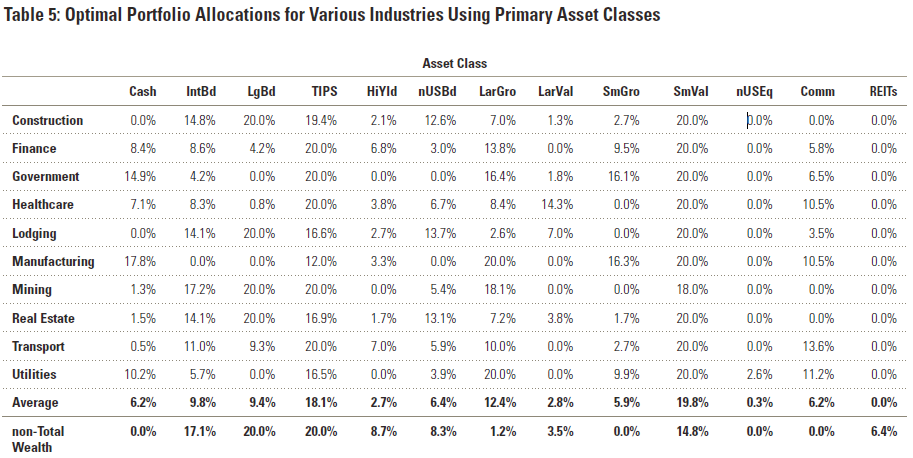

The end result of this analysis was a measure of how the volatility of an individual’s human capital has varied over time (depending on what industry they work in), which is itself then treated as an asset around which the rest of the portfolio is allocated, with the “typical” goal of minimizing risk for a given level of return. The end result of the various portfolios – depending on the individual’s industry, and assuming their human capital is 80% of their total net worth (e.g., an ag 45 worker) – is shown below (the bottom line is the non-industry specific Total Wealth allocation that would have occurred if human capital was ignored).

Source: "No Portfolio Is An Island" by Blanchett & Straehl

As the results reveal, there is significant variability from one industry to the next about what constitutes the “optimal” portfolio! Industries like manufacturing and transportation end out with significant allocations to commodities (allowing the portfolio to hedge the impact of higher commodity costs on those businesses), while industries like mining and real estate have no commodity exposure at all (as they will already benefit from rising inflation and higher commodity costs!). Similarly, the results found that industries like lodging and mining and construction are well hedged by a long bond exposure, while no allocation at all is needed for those working in government or utilities. And notably, the results find almost no allocation at all to non-US equities nor REITs once industry-specific exposures are accounted for, suggesting that those asset classes don’t actually seem to effectively hedge the economic factors that are already so impactful to (US) workers (and/or the benefits they bring are already covered by other asset classes)!

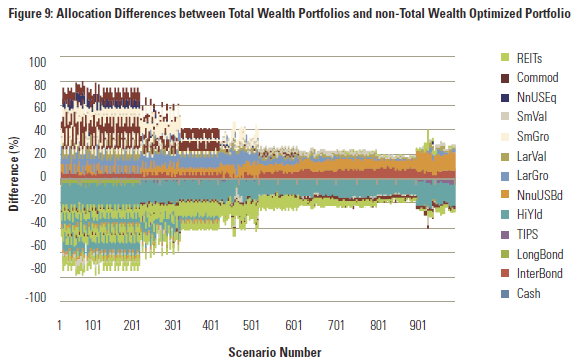

Notably, the chart above accounts for optimal allocations based only on the adjustments that might be made to the portfolio due to human capital, and not also accounting for pension and housing wealth (and the fact that all of these relative weightings of assets change over time). Accordingly, the graphic below looks at how the optimal allocation would change over time, after adjusting for all of these factors, versus how the portfolio would have been allocated looking at the portfolio wealth alone (as the scenarios increase, the investor is assumed to increase in age from their 30s to their 40s and ultimately to their 60s and 70s):

Source: "No Portfolio Is An Island" by Blanchett & Straehl

Once again, the optimal allocations accounting for human capital, and housing and pension wealth, vary significantly from the portfolios that ignore it; the deviations are largest in the earlier years, suggesting that human capital in particular has the greatest impact on the portfolio allocation. This leads to strategies that help to hedge the volatility of (human) capital in the early years (e.g., owning more in commodities and less in high-yield), and then strategies that help to hedge pension and housing wealth in the later years (e.g., slightly less in commodities and real estate, more in international bonds).

Practical Implications Of The Morningstar Paper For Financial Planners

On the one hand, the Morningstar research goes a long way to highlight the fact that just allocating a portfolio based solely on the portfolio alone may result in a significant misallocation of assets, given that for many (most?) people, their financial assets at best may only ever constitute half of their total net worth, and at many points is even a smaller percentage. In fact, when analyzed down to “just” the industry level – and recognizing the factors that can impact (employment) risk and wage growth across industries – the authors show that the optimal portfolio can in fact vary quite significantly.

On the other hand, the results also highlight the relative complexity of trying to create a client’s portfolio on this basis, and the potential challenge of convincing clients to deviate their allocations materially from the “traditional” advice, such as eschewing REITs in the portfolio because gaining exposure to those risk factors is already covered by other parts of their net worth. Similarly, if older clients already have a significant allocation to pension and Social Security wealth, they arguably need less fixed income in their portfolio and could hold more in equities, but that may still be difficult to justify in real time when a bear market occurs and the client’s (standalone) portfolio was heavily invested in the market! And unfortunately, as the Morningstar research perhaps unwittingly highlights, the depth of analysis and assumptions necessary to model the client’s holistic wealth – in order to adjust the portfolio around it – may make it difficult or impractical for most to implement immediately.

Nonetheless, arguably the Blanchett and Straehl research is just an extension of the more common version of this advice that many planners already give their clients, whether it’s owning less in TIPS when they already have an inflation-adjusted pension, reducing ownership of company stock (your job is already dependent on the health of the company, you shouldn’t make their retirement funds depend on the same company as well!), or sometimes adjusting a portfolio’s industry exposure based on a client’s job (e.g., clients working at a tech company might own less in tech stocks, or those working at a major industrial like GE might own less in the industrials sector). To say the least, the Morningstar research validates that if anything, these kinds of adjust-your-portfolio-around-your-job portfolio changes may still be understating their importance.

In addition, the Morningstar research still fails to account for even more individual-specific issues and constraints, that could impact the situation even further. For instance, as Arnott and Wu recently pointed out, younger adults have a greater risk of unemployment, which makes their human capital significantly more stock-like, and suggests that young people should own far less in equities than is traditionally thought. More generally, arguably anyone with a less stable job situation and more “stock-like human capital” should consider a more conservative portfolio to counterbalance this risk. And given the potential long-term impact to human capital by accelerating its growth rate, incorporating human capital considerations could also shift where it makes sense to “save” in the first place (e.g., by “investing” into education and job training rather than a retirement account).

The bottom line, though, is simply this: looking at a portfolio in isolation, without considering the rest of an individual’s household “wealth” (even its illiquid forms like pension/Social Security wealth, and human capital), can potentially cause a client to be significantly misallocated, taking potentially far too little or too much risk in particular asset classes or in their portfolio overall. While the details of how to “optimally” make these adjustments may be the domain of research for many years to come, the potential size of the adjustments – especially for younger people with a large amount of human capital – are too significant to ignore when planning for clients, and even crude adjustments to recognize how a portfolio might be changed to account for the risk of their career are likely better than making none at all!

For those who are interested, you can see a full copy of Morningstar’s Blanchett and Straehl paper “No Portfolio Is An Island” by clicking here.

So what do you think? Do you make adjustments to a client portfolio based on their employment and human capital? Do you think it’s a good idea to do so? What other factors – besides the size and time horizon of the portfolio itself – should be considered when allocating a portfolio?

Hi Michael. Dirk Cotton looked at approaching the Human Capital aspect in the form of putting it all together through a balance sheet approach in a recent blog post on this as well. Rather than regurgitate it … here’s the link http://theretirementcafe.blogspot.com/2014/11/the-household-balance-sheet.html … you bring up some very good points about this whole approach. Human Capital (HC) may be just as volatile as Financial Capital (FC) … so this would imply massive swings in allocation at precisely the wrong time! For example, the economy falls (e.g., 2008) and your once secure job (HC) that was once bond like would result in the once stock like allocation (FC) to have to be sold to supply temporary income – thus selling stocks low to get those bonds OR that money needed until a new job comes along. Neither component of the overall allocation is as stable as one would think. And about those government jobs – they’re not as stable either! Federal, State, County and City jobs were cut the last time around (and at other times too). Even military jobs come and go (they’re in a cutting cycle as we speak). This is an interesting approach and David’s work puts more light on the topic for conversation and consideration.

Actually, Mike Lonier wrote that as a guest blog on my website. I must admit that, given that I am retired and my posts are aimed primarily at retirees, I don’t focus much on human capital because it is about gone for most of us. I agree I should. These are all great posts, Michaels’, David’s and Mike Lonier’s. I’m inspired to give it more attention.

Whether or not young people have more risk of unemployment than older workers, I can tell you that it is a significant problem for older workers. I worked for several large companies and by the time we reached 50, we began to notice the scarcity of fellow employees in their 60’s. I’m pretty sure that once older employees lose a job, getting another is more difficult because of their age. If job security isn’t as shaky for older workers as younger, it’s shaky enough to be treated as risky.

I recently read that for most retirees, the greatest source of wealth is the present value of Social Security benefits, followed by real estate and only then, retirement savings. Considering all of a household’s assets is not only a logical thing to do, for most households it will be absolutely necessary.

Great post, Michael!

This seems like something that most financial advisors/advisers–if they are really financial advisors/advisers and not just brokers masquerading as advisors/advisers–would know, but is that not true? Where do financial advisors/advisers, and I guess that I am referring to IARs get their training/skills/education?

These problems arise with a couple of my clients who are over-confident and/or bored by mutual funds and want to invest in assets where they think they have an edge (but don’t). People who work in tech want to own tech stocks (not just their own). Real estate professionals own property beyond their principal residence. They are compounding the overweight in their Human Capital by owning the same stuff in their portfolios.

If I can’t win them over by explaining the value of diversification, I ask them to limit their play to money they are prepared to lose, and we isolate the allocation and results from the rest of the portfolio.

Dear Sirs,

let me comment this article as follows: In Europe, and especially in the German speaking countries, there is an array of SMEs,( some of them world players in their field) the so-called Mittelstand, where the group of industrial enterprises would build the “shadow assets” and the portfolio of securities of each member of such a family should be built accordingly ( taking into consideration the traits of such shadow assets). If someone would want to contact me on this subject, I would be pleased.

Hubert