Executive Summary

Although the aggregate divorce rate amongst Americans has fallen in recent decades, there has also been a concurrent (and dramatic) increase in the number of divorces for couples over age 50. The rise of the so-called “grey divorce” has created a number of uncommon and complex issues that financial advisors are helping their clients navigate, such as splitting what can oftentimes be substantial assets, including retirement accounts. Splitting an IRA, for instance, is generally pretty straightforward, but the matter becomes far more complicated for accounts that have ongoing 72(t) distributions.

As a starting point, it’s important to understand what a 72(t) distribution is in the first place. Although IRA accounts are intended to provide retirement funds for the owner, there can be emergent situations in one’s life for which an individual might not have the necessary cash on hand. Understanding that, Congress provided for a handful of exceptions that allow an individual to access the funds in their IRA accounts prior to age 59 ½ without triggering the dreaded 10% early withdrawal penalty. One of these exceptions includes the option to elect taking "substantially equal periodic payments" from the IRA, also known as 72(t) payments.

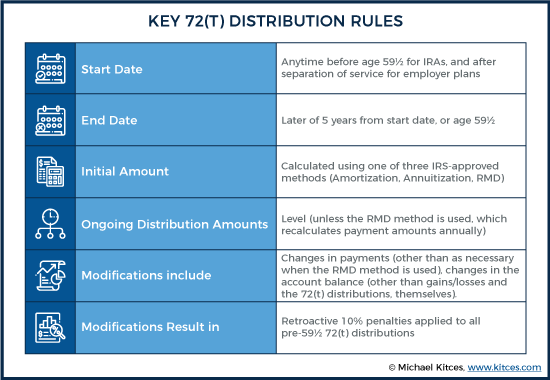

Although there are a few IRS-approved methods to calculate the exact amount of those substantially equal periodic payments, the key component is that the individual must continue to take those distributions “without modification” for the longer of five years, or until age 59 ½. Modifications can include (among other things) changing the amount of the periodic withdrawals (other than as allowed via the RMD method), taking an additional distribution on top of the 72(t) payments, changing the balance on the IRA account via roll-ins or rollovers out of assets, or making a non-taxable transfer of a portion of the account balance. And it’s that “non-taxable transfer” rule that can cause so much confusion for divorcing couples who need to split an IRA that is subject to 72(t) distributions.

Under normal circumstances, splitting an IRA that is not subject to a 72(t) distribution schedule between a divorcing couple is simply a matter of the custodian transferring the funds specified by the divorce decree from the current owner to a (new) IRA account in the name of the ex-spouse. However, since dividing an IRA pursuant to a divorce decree is, in fact, a non-taxable transfer, it seems possible that the IRS would deem that transfer to be a “modification” for IRAs subject to 72(t) payments, thus triggering the 10% penalty… plus interest!

Fortunately, though, over the years, the IRS has issued several Private Letter Rulings (PLRs) addressing this very conundrum. These PLRs have been rather accommodating to both ex-spouses. Transferor ex-spouses have been given the option to decrease future 72(t) distributions proportionally to the amount that was transferred out of the account. Meanwhile, transferee ex-spouses have not been required to continue to take 72(t) distributions, though they have been allowed to choose to do so if desired!

Ultimately, the key point is that, while divorce is a stressful event that often creates unforeseen financial hurdles for advisors and their clients to navigate the best they can (and sometimes without any formal guidance from the IRS on unclear taxation rules), there has at least been consistency (albeit on a case-by-case basis) in the rulings around the treatment of transferring the balance of an IRA that’s subject to 72(t) payments in a divorce.

Despite the fact that the divorce rate for younger couples has been falling in recent decades, roughly 40% to 50% of all U.S. marriages still end in divorce, according to the American Psychological Association. Which means that an unfortunately high number of couples will split before reaching the ‘magic’ age of 59 ½, when distributions can be taken from retirement accounts without any penalty.

Sometimes, cash flow problems, or less commonly, an early retirement, may have led one or both spouses to tap into IRA assets early (before 59 ½) via the use of specially scheduled annual payments, called a series of substantially equal period payments (abbreviated both as SoSEPPs and SEPPs), or more commonly, 72(t) distributions. And if accounts from which such distributions are being taken are split as part of the divorce proceedings, they can exacerbate an often already-complicated situation. Notably, there is no formal guidance from the IRS on the matter, and virtually all of the informal guidance available, via Private Letter Rulings made publicly available, in some cases directly conflicts with the IRS’s limited formal guidance on 72(t) distributions!

72(t) Distributions From IRA Accounts And The Imposition Of The 10% Penalty For Modifications

There’s a reason the “R” in “IRA” stands for “retirement”, and not “recreation” – it’s because Congress created the IRA (along with the 401(k), 403(b) and other tax-favored retirement accounts) to address the specific need of saving enough money during one’s working years to be able to support oneself during retirement.

Therefore, in an effort to encourage people to actually use funds in their retirement accounts for their intended purpose (retirement!), Congress attached a string to the money put into an IRA. More specifically, via IRC Section 72(t)(1), distributions from IRAs are not only subject to the usual income tax but also to a 10% penalty, unless one or more exceptions exist.

Notably, the first ‘exception’, provided by IRC Section 72(t)(2)(A)(i), is really more of ‘the rule’ than an exception, as it allows an IRA owner to take distributions from their IRA after the attainment of age 59 ½ without a penalty. This, in the eyes of Congress, was an appropriate age at which to consider someone ‘retired’ (or at least, ‘close enough’), and thus, able to use their IRA savings for its intended purpose.

Of course, Congress also understood that, from time to time, people may put money into retirement accounts and, for one reason or another, may need to access some or all of those funds prior to reaching retirement age (59 ½). Thus, they crafted a number of other narrow exceptions to the general rule – what Congress deemed permissible reasons to break the “I’m putting this money away for retirement” covenant one makes when contributing funds to a retirement account.

Such narrow exceptions to the 10% penalty include (but are not limited to) distributions:

- To beneficiaries after an owner’s death;

- To IRA owners who are considered disabled, though they must be “unable to engage in any substantial gainful activity” due to a “medically determinable physical or mental impairment,” expected to last indefinitely or result in death, as defined in IRC Section 72(m)(7);

- Made on account of an IRS levy;

- For medical expenses in excess of 10% of the IRA owner’s adjusted gross income (AGI);

- Used to pay qualified higher education expenses of the IRA owner or other qualified individuals; and

- Up to $10,000, which are used towards the first-time purchase of a home.

Congress, however, also included a broader exception to the 10% penalty rule that allows individuals to use a limited amount of ‘retirement’ dollars for an ‘early retirement’ (or at least taking ongoing early withdrawals as though they were in early retirement).

More specifically, distributions that are “part of a series of substantially equal periodic payments (not less frequently than annually) made for the life (or life expectancy) of the employee or the joint lives (or joint life expectancies) of such employee and his designated beneficiary” are called “72(t) distributions”, and are exempted from the 10% early withdrawal penalty by IRC Section 72(t)(2)(A)(iv). In addition to IRAs, these 72(t) distribution schedules may also be established for company plans after an employee has separated from service.

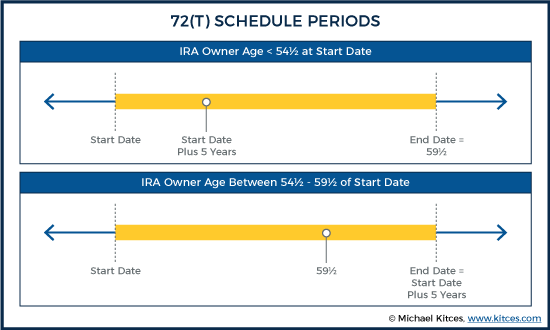

IRC Section 72(t)(4) further provides that in order to maintain the penalty-free nature of 72(t) distributions once they begin, they must continue without “modification” for the longer of:

- five years, or

- until the IRA owner turns 59 ½.

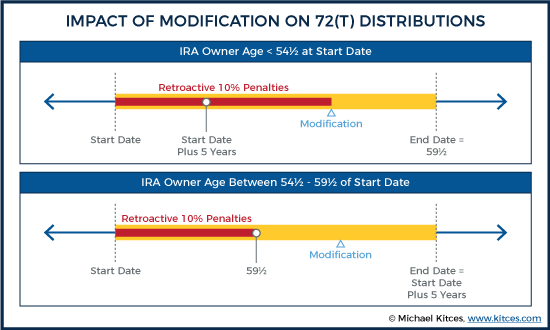

In the event a modification does occur before 72(t) distributions are allowed to terminate, the 10% early withdrawal penalty is retroactively assessed on all previously-penalty-free 72(t) distributions taken prior to the IRA owner’s attainment of age 59 ½ (plus a late interest “penalty” on the penalties, themselves, for not having paid them in the original year!).

Triggering A ‘Modification’ To 72(t) Substantially Equal Periodic Payments

Unfortunately, despite the obvious importance of (avoiding) a modification for those using 72(t) distributions to tap into retirement funds early, there is virtually nothing in the Internal Revenue Code, nor the Treasury Regulations, that adequately describes what, exactly, constitutes a modification. Instead, most of the information we have about modifications, and indeed, the 72(t) rules in general, comes from Revenue Ruling 2002-62.

Sections 2(.01)(a), 2(.01)(b), and 2(.01)(c) of Revenue Ruling 2002-62 provide that, in general, 72(t) payments must be calculated using one of three methods approved by the IRS in Revenue Ruling 2002-62 (the IRS has also authorized other distribution methods by specific taxpayers via Private Letter Rulings (PLRs), such as PLR 200943044).

The three methods outlined by the Revenue Ruling are the:

- Fixed Amortization Method,

- Fixed Annuitization Method, and

- Required Minimum Distribution (RMD) Method.

Revenue Ruling 2002-62 further explains that once an initial 72(t) payment is calculated using either the fixed amortization or fixed annuitization method, “the annual payment is the same amount in each succeeding year.” Thus, any change in the distribution amount from one year to the next, when using either of these methods, would be considered a modification, and would trigger the retroactive assessment of the 10% penalty to all previous 72(t) distributions made before the account owner reached age 59 ½.

When using the RMD method, 72(t) payments are calculated using a formula similar to the manner in which required minimum distributions are calculated for IRA owners 70 ½ (hence the name), by dividing the current account balance by the IRA owner’s life expectancy in that year. As such, annual payments determined using this method can, and generally will, vary as they are recalculated each year.

Payments determined by the RMD method, however, must still be calculated in accordance with the prescribed rules. So, for instance, if there was an incorrect life expectancy factor, or an “unreasonable” balance (though Section 2(.02)(d) of Revenue Ruling 2002-62 provides significant flexibility when selecting a “reasonable balance”) used in the calculation, a modification could occur, once again triggering retroactive 10% penalties on pre-59 ½ 72(t) distributions.

Because the RMD method almost always produces the lowest cumulative 72(t) payments, it should rarely, if ever, be used as the initial method of calculating distributions, as the primary goal is generally to create the largest possible 72(t) payment from the smallest possible account balance. Revenue Ruling 2002-62 does, however, allow a one-time switch from either the annuitization or amortization method to the RMD method. This can be useful when 72(t) payments are no longer needed, but must continue to be taken to avoid modification.

Section 2(.02)(e) of Revenue Ruling 2002-62 provides further guidance on modifications, stating:

Thus, a modification to the series of payments will occur if, after such date, there is (i) any addition to the account balance other than gains or losses, (ii) any nontaxable transfer of a portion of the account balance to another retirement plan, or (iii) a rollover by the taxpayer of the amount received resulting in such amount not being taxable.

In simpler terms, once a 72(t) payment plan has begun, to avoid modification, an IRA owner must follow both of these requirements:

- Continue taking the same annual payments (or, in the case of the RMD method, be calculated and distributed correctly) until the completion of the 72(t) schedule; and

- Avoid any changes to the account balance(s) on which the 72(t) payments were calculated, other than changes via gains or losses within the account, and, of course, by the 72(t) distributions themselves!

And again, if an individual fails to meet one of these requirements, the 10% penalty will be assessed on all 72(t) payments that were taken before the individual reaches age 59 ½, which can result in some very steep penalties!

Example 1: Chris, who turned 57 years old on July 10, 2019, began taking $10,000 annual 72(t) distributions from his only IRA in 2015, at age 53. On August 1, 2019, Chris’s home was damaged by a flood.

Chris, who did not have flood insurance or an adequate non-retirement account emergency reserve, was forced to take an additional $15,000 from his IRA to pay for flood repairs. Because this additional distribution occurred prior to Chris attaining age 59 ½, it created a modification of the 72(t) schedule.

As a result, the 10% early distribution penalty will be retroactively assessed on all of Chris’s pre-59 ½ 72(t) payments (which, in this case, include all of Chris’ 72(t) payments). Thus, Chris will be retroactively assessed a $10,000 x 10% = $1,000 penalty, plus interest(!), for each of the 72(t) payments taken in 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018, and 2019 (in addition to the $15,000 x 10% = $1,500 penalty for the distribution taken in 2019 after the flood), for a total penalty of $6,500 plus interest!

In Example 1, above, by taking an extra distribution outside of the 72(t) schedule, Chris failed to follow the rule requiring him to continue taking the same annual payment, triggering the 10% penalty on all payments taken, since he had not yet reached age 59 ½. Even though he continued taking the payments themselves. Because any additional distrbution from an IRA making 72(t) distributions is treated as a modification of the entire distribution schedule!

Example 2: Janet, who turned 61 years old on September 2, 2019, began taking $12,000 annual 72(t) distributions from her only IRA in January of 2016 after losing her job at age 58. In 2017 Janet found new employment but has continued to correctly take her $12,000 72(t) distribution each year.In June of 2019, Janet retired. At the time, she had accrued $17,000 in her new employer’s 401(k) plan. Wanting to simplify her life as she started retirement, Janet rolled the $17,000 401(k) balance into her IRA, creating a modification (a change in the account value other than via gains, losses, or 72(t) payments) of the 72(t) schedule prior to the completion of 5 years.As a result, the 10% early distribution penalty will be retroactively assessed on all of Janet’s pre-59 ½ 72(t) payments. Thus, Janet will be retroactively assessed a $12,000 x 10% = $1,200 penalty, plus interest(!), for her January 2016, 2017, and 2018 distributions (since she turned 59 ½ in March 2018, after she took her January 2018 distribution), for a total penalty of $3,600, plus interest. (Note, however, that no 10% penalty would be retroactively assessed for Janet’s 2019 distribution, as she was already over 59 ½ at the time.)

In this example, Janet failed to follow the rule requiring her to avoid account balance changes when she rolled over her 401K balance to the IRA account from which she was taking 72(t) payments. This resulted in three of her four 72(t) payments (those taken before she turned 59 ½) to be subject to the 10% penalty.

Had Janet waited until February 2021 to transfer her 401(k) balance to her IRA, or simply rolled over the 401(k) balance into a separate IRA account not encumbered by a 72(t) payment schedule, she would have avoided creating a modification, and associated retroactive penalties.

The Mechanics Of Splitting IRAs Pursuant To A Divorce

An interesting question begins to emerge when we consider the 72(t) rules in the context of divorce… How do you split an account from which 72(t) payments are being made, without triggering a modification?

To fully appreciate the complexities and practical challenges presented by such a situation, it is necessary to understand the basic rules for splitting an IRA in divorce in the first place. Unlike qualified retirement plans such as 401(k) and defined benefit pension plans, which must be split via a qualified domestic relations order (QDRO), IRAs are split pursuant to divorce decrees or marital separation agreements (MSAs). Once such a document has been approved (in accordance with state law), it can be presented to the IRA custodian.

From there, the IRA custodian will transfer the divorce decree/MSA-approved portion of the IRA balance from the current IRA owner, as a non-taxable transfer to an IRA account in the name of the ex-spouse.

The ex-spouse receiving the funds must generally complete new account paperwork with the custodian splitting the IRA account, if such an account does not already exist. Afterward, if the receiving ex-spouse wants to change custodians, they can execute a transfer or rollover of the funds within their own IRA.

No Exception To The 10% Penalty For Distribution Of IRA Funds Received Via Divorce

Those persons receiving IRA funds pursuant to a divorce should be sure to understand that there is no exception to the 10% penalty for distributions from an IRA because of divorce. Thus, while the actual splitting of the IRA does not result in the imposition of a tax or a penalty, distributions by the receiving spouse from their own IRA after the transfer occurs are subject to the 10% early withdrawal penalty if the the receiving spouse is not yet 59 ½ (or unless a specific exception to the 10% early withdrawal penalty applies).

Oftentimes, this comes as a surprise to individuals, especially those who may also be receiving qualified plan funds pursuant to a QDRO, since funds in a qualified plan allocated via a QDRO, that are later distributed from that same plan (i.e., they weren’t rolled over to another plan or IRA) are exempt from the 10% penalty.

But since, as noted above, IRAs are not split via a QDRO, the QDRO exception does not apply to distributions from IRAs. Ever!

Thus, in the event a receiving ex-spouse would like to take a distribution of some or all of their newly acquired IRA funds from their MSA or divorce decree, and without incurring the 10% penalty, they must either be 59 ½ or qualify for one of the exceptions to the 10% penalty that apply to IRAs (including the option to set up a 72(t) payment schedule).

What Happens When You Split An IRA In Divorce From Which 72(t) Payments Are Being Made?

Once the rules for splitting an IRA in divorce are understood, it’s then possible to explore why the question, “How do you split an account from which 72(t) payments are being made without triggering a modification?” is so problematic.

Recall that when IRAs are split pursuant to a divorce, the result is that the receiving ex-spouse gets their portion of the IRA balance via a non-taxable transfer from the original owner. And now consider that Section 2(.02)(e) of Revenue Ruling 2002-62, in no uncertain terms, states:

…a modification to the series of payments will occur if, after such date, there is (i) any addition to the account balance other than gains or losses, (ii) any nontaxable transfer of a portion of the account balance to another retirement plan… (emphasis added).

Frankly, that’s about as cut and dried as it gets when it comes to tax rules. The Revenue Ruling quite literally says, any nontaxable transfer of a portion of the account is a modification! So, clearly, a nontaxable transfer of a portion of an account balance would run counter to that rule, and would, therefore, trigger a modification… right?

Not so fast.

Incredibly, it would appear that when the IRS drafted Revenue Ruling 2002-62, they simply did not contemplate that a person receiving 72(t) payments from an IRA account might get divorced and that as part of that divorce, they might be required to transfer a portion of their IRA balance to their ex-spouse. After all, would they really want to trigger retroactive 10% penalty amounts (and interest) on an individual simply because they were complying with a state-court-ordered division of assets? Unlikely.

But when there’s a Revenue Ruling out there that says any nontaxable transfer creates a modification, and you have to make such a transfer, and there is no additional guidance that would lead you to believe that there are any exceptions to this rule, what’s a person to do?

Private Letter Rulings Can Provide Taxpayers With Useful Guidance

In a number of taxpayers’ cases, the answer to figuring out how to deal with a nontaxable transfer of IRA assets to your ex-spouse due to a divorce ruling ended up being “go for a Private Letter Ruling (PLR)”. Private Letter Rulings are sort of like a mini Tax Court case, in which a taxpayer argues their position (in writing) to the IRS, and then the IRS decides how to treat the situation, providing clarity for the taxpayer.

Furthermore, as an added bonus for the rest of us, the IRS makes their response (less the redaction of some potentially-personally-identifying information) publicly available shortly after apprising the taxpayer seeking the PLR of their decision, in an effort to promote transparency.

Technically, a PLR cannot be relied upon by anyone other than the taxpayer receiving it. But when IRS rulings are consistent on the same (or similar) matter over a period of time, they can be a good indication of how the IRS would likely treat another matter with a similar set of facts and circumstances.

To eliminate any doubt, in a perfect world, all taxpayers would seek their own PLR prior to the divorce-triggered splitting of an IRA from which 72(t) payments are being made. But that won’t happen. Because even though the receipt of such a ruling would give taxpayers a definitive answer as to how the IRS would view their situation, the PLR process is both time consuming and expensive. From start to finish, the whole process can last a year or longer, and the IRS fees for PLRs (which vary depending upon the type of ruling requested), can easily exceed $10,000! And that’s before you add in any professional fees to an accountant or attorney prepare the ruling, which can easily double the all-in cost.

Not surprisingly, few taxpayers are willing to spend that type of time and money, particularly during a divorce (when time and money are often even more scarce than normal). The good news though, is that over the years, there have still been enough rulings on the matter to get a good gauge as to the IRS’s position to the extent that many tax professionals and custodians now feel a PLR is unnecessary (because the IRS’s position is so clear).

Furthermore, in response to PLR requests involving the treatment of the division of IRAs from which 72(t) payments are being made, the IRS has been rather flexible and accommodating to both the transferor ex-spouse and the transferee ex-spouse.

Options For Ex-Spouses When Splitting An IRA From Which 72(t) Distributions Are Being Made

When it comes to determining the impact of transferring a portion of one’s account balance to an ex-spouse pursuant to a divorce, there are a litany of PLRs that all reach the same conclusion: it’s OK!

Thus, even though Revenue Ruling 2002-62, in no uncertain terms, said there cannot be any nontaxable transfers, PLRs dealing with transfers pursuant to divorce have consistently sent a different message.

“Just kidding! We really didn’t mean any nontaxable transfers. Just most. This one’s OK.”

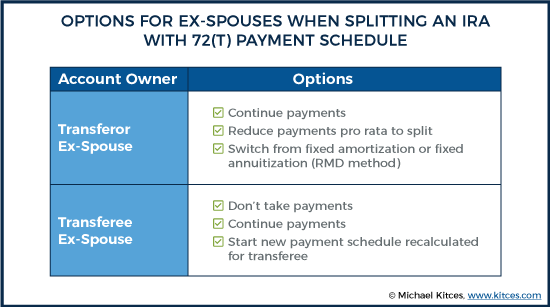

A Transferor Ex-Spouse Must Continue 72(t) Payments, But Has Options To Reduce Payment Amounts

While PLRs suggest that the part of the equation prohibiting any account balance changes to avoid a modification event is not an issue when the account is split due to divorce, what about the part of the equation that requires the same annual 72(t) payments be taken from the account? What should the transferring spouse do once the account is divided with their ex-spouse?

Well, as noted above, the IRS has been flexible. To begin with, continuing existing payments is, in essence, maintaining the status quo of the 72(t) schedule, so that is certainly one option. Of course, if someone is giving away a good chunk of their IRA money, they may wish to reduce their 72(t) payments as well, so as to not liquidate the IRA at an expedited (and potentially dangerously-depleting) rate. To that end, many PLRs (such as PLR 201030038, PLR 200052039, PLR 200717026, and PLR 200050046) have allowed the transferor ex-spouse to reduce payments in proportion to the amount transferred to the receiving ex-spouse’s IRA.

Example 3: Shira and Lance are in the final phases of a divorce. Shira, who is 57 years old, began taking $14,000 annual 72(t) distributions from her IRA 4 years ago, and has 2.5 years left to continue the distributions without modification until she turns 59 ½.

As part of the divorce decree, Shira will transfer 50% of her current IRA balance to Lance. Therefore, based on guidance from available PLRs, it would be reasonable to believe that Shira could reduce her current $14,000 annual distributions by 50%, and take only $7,000 per year, going forward, until she reaches 59 ½ (at which point her 72(t) schedule would be done, and she could take as much or as little as she wants).

If a transferor ex-spouse wishes to reduce their ongoing 72(t) payments even further (beyond just an amount in proportion to the amount transferred to the receiving ex-spouse) they could also make use of the ability to make a one-time switch to the RMD method, as authorized by Revenue Ruling 2002-62 (assuming they were not already using the RMD method).

Finally, it should be noted that divorce is never a reason that would allow the transferor ex-spouse to stop taking 72(t) distributions altogether. Rather, the choice is simply whether to continue the original distributions, or reduce them on a pro-rata basis. Either way, distributions of some (appropriate) amount must continue for the longer of 5 years, or until the account owner reaches age 59 ½, for the 72(t) schedule has been reached.

Ex-Spouses Receiving IRA Funds Don’t Need To Take 72(t) Distributions (But Can, If They Want To)

Over the years, PLRs have also granted ex-spouses receiving the IRA assets flexibility when determining what amount, if any, they should take from their newly acquired IRA funds to satisfy 72(t) payments established by their ex-spouse. For those individuals who wish to preserve as much of the account as possible, the simplest answer may also be the most obvious… just don’t take any distributions if they don’t want to!

After all, the ex-spouse receiving the newly divided IRA account didn’t set up the 72(t) schedule – it was the transferor ex-spouse. Thus, the receiving ex-spouse is under no obligation to continue receiving payments, a fact confirmed by the IRS in numerous PLRs, including PLR 200116056, PLR 200050046 and PLR 200027060.

That being said, if the receiving ex-spouse is under 59 ½ at the time of the transfer, and they need income to meet their living expenses, they may wish to continue taking distributions, in some manner, from the new IRA. In some PLRs, such as PLR 9739044, the receiving taxpayer asked the IRS if they could continue taking their “share” of the original 72(t) payment amount, in proportion to the amount of the account they received. The IRS obliged.

Alternatively, another option for the receiving ex-spouse is to simply start a new schedule by starting their own standalone 72(t) distribution payments, using their current account balance and their current age. The benefit of doing so is that in certain situations, such as when the receiving spouse is much older than the transferor spouse was when they began their initial 72(t) payment schedule, it might allow for an increase in the annual payment amount. The downside, of course, is that by doing so, the receiving spouse would be starting a new distribution schedule, which itself would then need to last at least five years (or until they turned 59 ½, if longer).

Divorce is a challenging time for many couples and is often a period rife with stress and uncertainty. Adding money problems to the mix that require tapping retirement accounts early can exacerbate those issues. And if tapping retirement accounts early involved 72(t) payments, the uncertainty and stress levels can be dialed up even further, as CPAs, attorneys and other practitioners attempt to guide couples through a challenging maze of rules for which there is little formal guidance.

Thankfully, however, over the years there has been a significant volume of non-formal guidance accumulated in the form of PLRs. And while none of these rulings is authoritative to anyone other than the taxpayer who initially sought it, the consistency of the IRS in its decisions has shed significant light as to how it views the splitting of accounts during a divorce from which 72(t) payments are being made.

Specifically, and contrary to its own more formal guidance in Revenue Ruling 2002-62, the IRS has repeatedly authorized taxpayers to make nontaxable transfers of a portion of their account balances to ex-spouses pursuant to a divorce decree or separation agreement. In addition, the IRS has given both the transferor and receiving ex-spouses flexibility in terms of adjusting payments, by giving the transferor the ability to reduce payments ratably, and the receiving spouse the option of stopping payments altogether, continuing with a share of the existing payments, or starting a new 72(t) schedule of their own.

Ultimately, the best thing for a taxpayer is to seek their own PLR from the IRS. However, given the time and expense of such rulings, few taxpayers will do so, leaving the financial advisors, CPAs and attorneys left trying to decide to what extent they feel comfortable relying on previous, non-authoritative IRS guidance, provided to other taxpayers.

Really interesting and helpful article! What if the transferring spouse is required by the MSA to transfer the entire IRA balance to the transferee spouse. Then are they off the hook for ANY further 72t payments? Seems like that would be a sneaky way to stop having to make them.