Executive Summary

One of the more surprising features of the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA) of 2025 was the introduction of a new type of retirement account intended to be opened and contributed on behalf of minor children, which the law named the Trump Account (TA). Conceptually, the purpose of Trump Accounts is to give kids a head start on saving for retirement, and so many of the account's aspects mirror those of traditional IRAs; however, there are unique rules for TAs that take effect from birth through age 17.

For instance, TA contributions are generally limited to $5,000 per year (up to $2,500 of which can be from an employer). But certain organizations, including the Federal, state, and local governments and 501(c)(3) charitable organizations, can contribute additional funds (including an initial $1,000 'pilot' contribution by the Federal government for children born in the years 2025 through 2028). And while TA contributions from individuals are made on an after-tax basis, contributions from employers and government and charitable organizations are made pre-tax, giving the TA many of the same characteristics as a traditional IRA with a mix of pre-tax and after-tax funds. So, when funds are eventually withdrawn from the account – which (like IRAs) can only be done penalty-free after age 59 ½ without a specified exception – they're a mix of both tax-free (i.e., from after-tax contributions) and taxable dollars (from pre-tax contributions and investment growth over time).

The caveat, however, is that many of the issues that often make traditional IRAs problematic for their owners – including pre-tax dollars being taxed at ordinary income tax rates on withdrawal, Required Minimum Distributions (RMDs), and the "10-year rule" for most beneficiaries after the death of the account owner – also apply to TAs. And with the potential for TAs to be funded at a very early age and left to compound and grow for 60 years or more, it's possible that they'll eventually create the very same tax headaches in the future that owners of large traditional IRAs are dealing with today.

Thankfully, there are other vehicles available for parents to consider when giving funds to their kids. In addition to 529 plans (which can grow tax-free to be used for qualified higher education expenses), one option that worth exploring is a taxable custodial (e.g., UTMA or UGMA) account. Although taxable accounts don't receive tax-deferred treatment on investment income, that fact could actually turn out to be an advantage because of the "kiddie tax" rules, which allow up to $2,700 of qualified dividends and capital gains to be realized tax-free for dependent children. As a result, a custodial account could have significantly more "basis" than a TA at age 18 and beyond – meaning that the TA will end up generating more taxable income in the future (and be taxed at higher rates on that income due to the ordinary income treatment of gains upon withdrawal)!

One factor that could make TAs more favorable is the ability to convert TA funds to Roth, which could allow a TA owner to pay tax on the funds in their account at relatively low rates early in their career and allow them to grow tax-free thereafter. However, unless the owner has funds available outside of the account to pay the actual tax on the conversion, they'd need to withdraw from the account to pay that tax (and pay tax plus an early withdrawal penalty on that amount as well), significantly reducing the amount that's left in the Roth account to grow tax-free. Which means that even with the ability to convert to Roth, the taxable account could still come out ahead in the end (or at least not be so far behind as to be worth sacrificing the greater flexibility of the taxable account's funds to be used pre-retirement).

The key point is that when it comes to saving for kids, starting to save at an early age is far more important than what type of account those savings go into. While many illustrations of TAs project how their value can grow to eye-popping levels over time, the reality is that similar (or even better) results can be achieved in other types of accounts that have far more flexibility than TAs. And so while TAs can serve as a good conversation starter with parents who are interested in saving for their kids (and it may even be worth opening a TA just to receive the 'free' $1,000 pilot contribution if there's a child who is eligible for it), it may be best to involve other types of accounts in the discussion as well – since they could prove to be an as good or better option for growing a child's savings for the long term!

When the "One Big Beautiful Bill Act" (OBBBA) was signed into law on July 4, 2025, it created a new type of savings account, dubbed the Trump Account (TA), which can be opened and funded beginning on July 4, 2026. The IRS also released some initial guidance on TAs in late 2025, with the intention to issue formal regulations sometime in the near future. While there are still some questions about how TAs will work operationally that will need to be resolved before the official July 4, 2026 launch date, it's mostly clear how they'll work from a tax planning perspective.

At a high level, the TA is a modified version of a traditional IRA, with a twist: It can only be opened and contributed to on behalf of children prior to the year of their 18th birthday. And so unlike standard IRAs, which are only rarely used by minors since they require the owner to have earned income to be able to make contributions, TAs are meant explicitly to be funded by minor children with little to no income of their own.

The TA's ostensible purpose is to incentivize giving children a head start on their retirement savings at an early age. It does this using the time-honored trick of tax deferral (since interest, dividends, and capital gains in the TA aren't taxed until they're withdrawn from the account), ensuring that the account's growth won't be dragged down by taxes on the income generated by its investments. Additionally, TAs are designed to allow contributions from multiple sources, including not only parents and relatives but also employers, charities, and government organizations, as will be discussed more below.

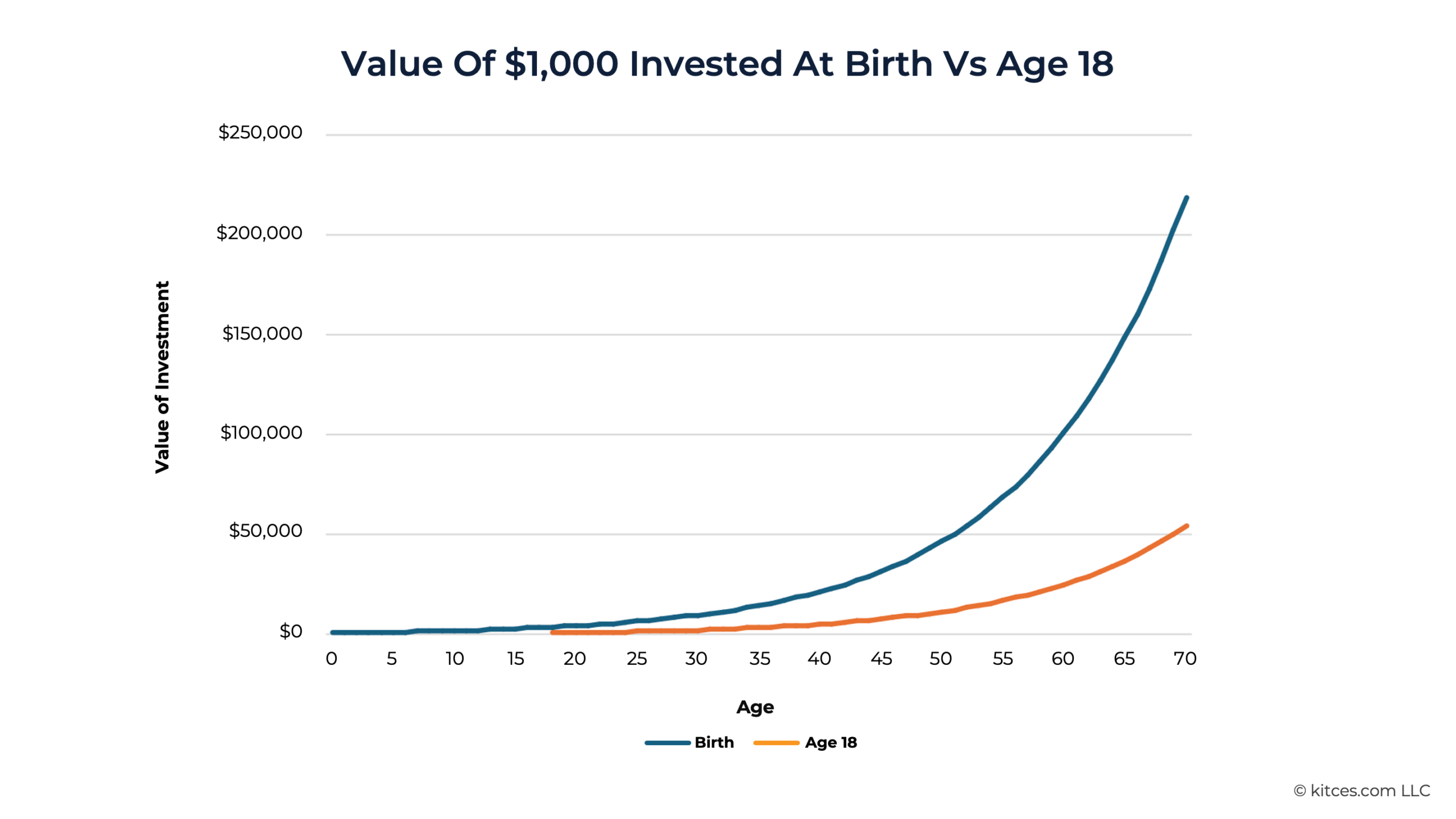

There are clearly benefits to getting a head start on saving for retirement. The basic math of compounding dictates that adding just a few additional years for an investment to grow can have outsized effects on its value at the end of the timeline.

For example, if a person who is 18 years old today invests $1,000, and that amount grows at 8% per year on average, the value of the initial contribution when the person reaches age 70 would be $1,000 × 1.08^(70−18) = $54,706; over 54 times the original investment. But if a newborn baby has that same $1,000 invested on their behalf, the investment's value when they turn 70 would be $1,000 × 1.08^(70) $218,606; over 218 times the initial investment. With a time horizon that stretches over decades, each additional year that the investment is allowed to grow can add sizeable amounts to the ending value, making it optimal to start saving as soon as possible.

In short, any way to get people to start saving for retirement earlier – even when they're children with no income of their own to invest – is a good thing, particularly with major questions about whether Social Security will be able to fund as large a portion of retirement benefits in the future as it does today.

The question, though, is whether TAs create enough of an incentive to make them the right vehicle to invest in on a child's behalf. There's already no shortage of ways for parents to save money for their children's benefit, from 529 plans to regular (non-TA) traditional and Roth IRAs to taxable UTMA or UGMA custodial accounts – all of which have their own flavors of tax incentives for various saving purposes. And so, TAs really only make sense as a savings vehicle if they represent an improvement over those other options.

As it turns out, there are many reasons why TAs may not be the right choice for saving money on a child's behalf. Which we'll get to below, but first it's necessary to understand how TAs work in order to compare them with the other available savings options.

The Rules For Trump Accounts

As noted above, TAs are built on the 'chassis' of a traditional IRA. However, there are many rules unique to TAs that set them apart from other account types, particularly when the account owner is age 17 and younger.

Contribution Rules

Starting on July 4, 2026, TAs can be opened and contributed to on behalf of a child (the "beneficiary") from the year of their birth through the year in which they turn 17. Contributions during this period can be made to a TA in three ways: Direct contributions, employer contributions, and "qualified general contributions", as spelled out below.

Direct and Employer Contributions

The simplest TA contributions are direct contributions, which are made in cash with after-tax dollars (i.e., contributions are non-deductible) and can be made by any individual – the beneficiary themselves, or parents, grandparents, friends, etc., of the beneficiary on their behalf.

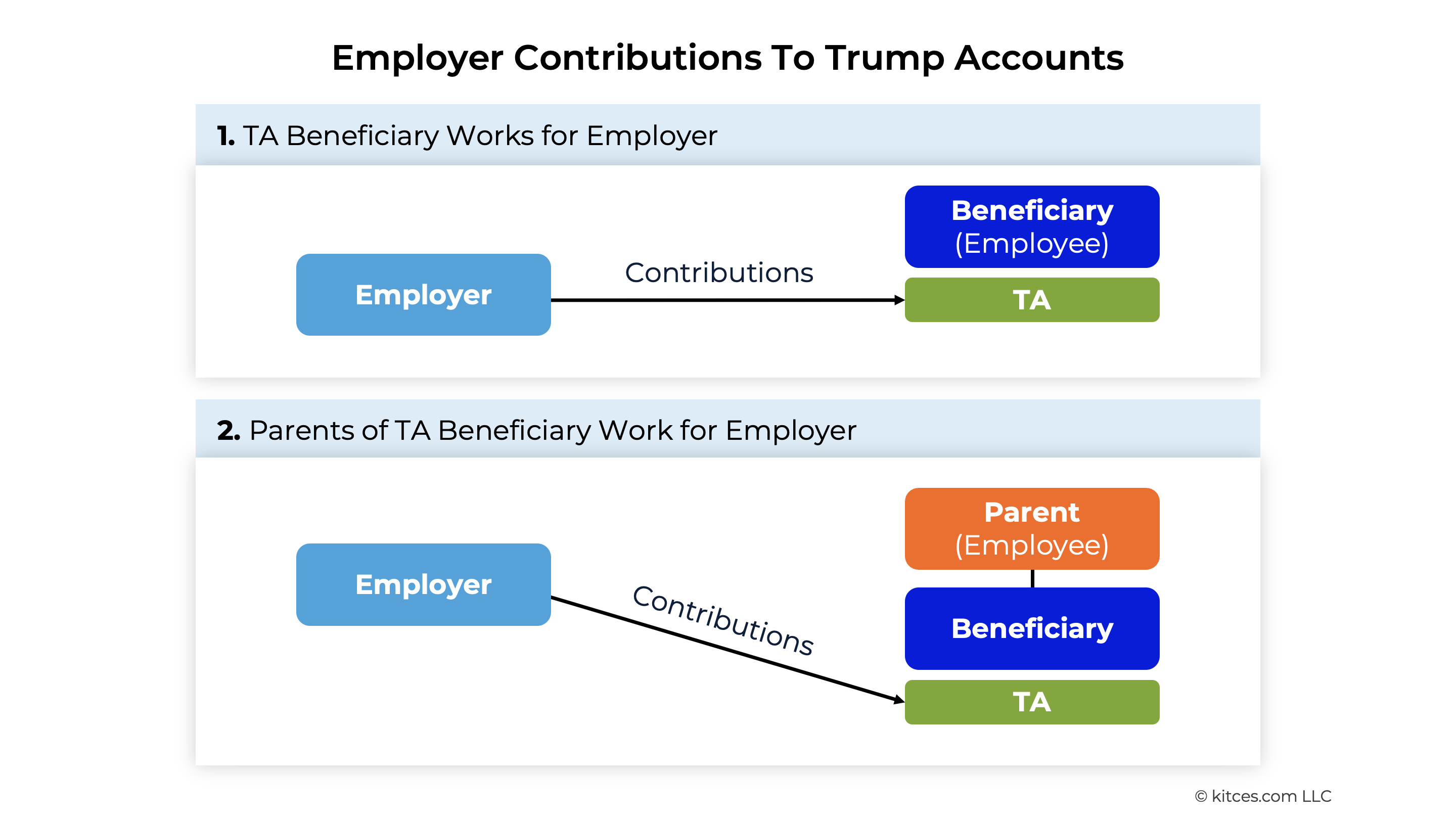

TAs also allow employers to make contributions on a pre-tax basis. Employer contributions can be made either to an employee's own TA, or to the TA of the employee's dependent child. In other words, if a TA beneficiary is old enough to work themselves, their employer can contribute to their account; otherwise, if a parent has a dependent child for whom they open a TA, the parent's employer can contribute to the account instead.

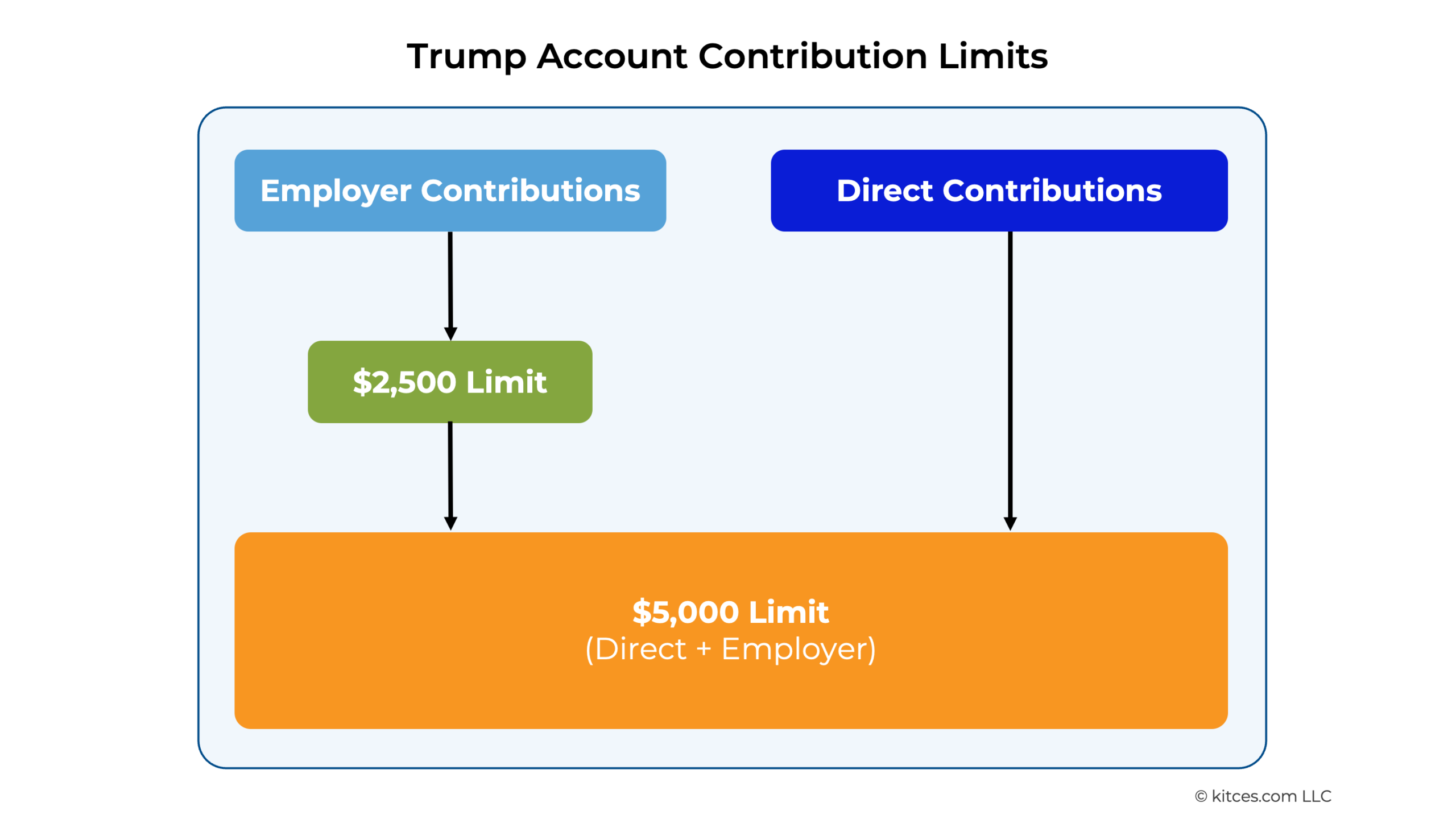

The total amount of combined direct and employer contributions to a TA is capped at $5,000 per year starting in 2026. However, employer contributions are capped at $2,500 per employee, meaning that of the total $5,000 combined annual contribution, only $2,500 can come from an employer, as shown below.

Both the $5,000 combined contribution limit and the $2,500 employer contribution limit will be indexed to inflation starting in 2028.

Nerd Note:

The text of the law regarding employer contributions to TA specifies that the $2,500 limit applies per employee, not per beneficiary. In other words, a TA beneficiary who both has their own job and is a dependent of their parents could receive up to $2,500 each from both their own employer and one of their parents' employers. Or they could receive contributions from both parents' employers, if both parents work but the beneficiary doesn't. However, if a parent has multiple dependents with TAs, their employer can only contribute up to $2,500 in aggregate to all beneficiaries: for example, a parent with two dependents could have their employer contribute up to $2,500 to either dependent's TA, or $1,250 to each dependent's TA, but not $2,500 to each.

Qualified General Contributions

Unlike direct and employer contributions, which are allowed in many other types of tax-preferred accounts, qualified general contributions are unique to TAs. These contributions can only be made by the Federal government, state or local governments, and 501(c)(3) charitable organizations, which can elect to contribute directly to TAs on their own. However, entities that make qualified general contributions have limited ability to pick and choose which TAs to contribute to: They can only restrict contributions to certain "qualified classes" and must contribute to all eligible TA owners within those classes. The classes are defined as: (1) all TA beneficiaries who have not reached the year of their 18th birthday; (2) all TA beneficiaries within a certain state or geographic area containing at least 5,000 TA beneficiaries (and who have not reached the year of their 18th birthday); or (3) all TA beneficiaries born in a specific calendar year (and who have not reached the year of their 18th birthday).

Qualified general contributions are not included in the $5,000 limit on direct and employer contributions. So, a TA beneficiary could theoretically receive more than $5,000 in contributions to their account each year, provided they are part of a qualified class receiving qualified general contributions from a state/local government or charity.

The first example of a qualified general contribution in practice was the recently announced commitment from the billionaire Dell family to fund contributions of $250 each into TAs for eligible children age 10 and under. However, that contribution is only available to children living in zip codes where the median household income is no more than $150,000 (this is because contributions can't be limited on the basis of the recipient's income, which doesn't meet the "qualified class" definition above, whereas limiting contributions to specific areas – and filtering for areas that fall under a certain median income – is allowed).

It is not yet known whether (or how many) other states, localities, or charities will eventually follow suit and implement TA qualified general contribution programs. While the concept is interesting, the reality is that each general contribution must by definition fund at minimum thousands (and perhaps millions) of TAs – meaning that they require substantial resources to fund, which even then might not amount to materially large contributions for individual recipients. For example, the Dells' contribution, totaling $6.25 billion in aggregate, divides out to just $250 per recipient.

Given the scale of funding needed to distribute qualified general contributions to TAs en masse, then, it could take years for more entities to roll out their own programs. To that end, it's likely better to think of qualified general contributions as a potential supplement to direct contributions made by the beneficiary or their parents or employers, rather than the core source of funds for future retirement savings. Because the amounts being contributed via governments or charities at the moment won't support their recipients' future retirement income needs on their own.

2025-2028 Pilot Program

One last type of TA contribution, currently available on only a temporary basis, is a U.S. government pilot program to contribute $1,000 to a TA for every U.S. citizen born in the years 2025 through 2028. Under the pilot program, parents of eligible children can elect to have the government open a TA and deposit the $1,000 pilot contribution on their child's behalf.

Notably, the $1,000 pilot contribution is an "opt-in" program, meaning that parents of eligible children (who generally must be the parent who claims the child as a dependent on their tax return) must affirmatively make an election for the government to open and fund the child's account. To do this, the parent will need to either file the new Form 4547 (currently published by the IRS in draft form) or fill out a form online to make the election at https://trumpaccounts.gov/.

Even though TAs can't be opened before July 4, 2026, it appears as though Form 4547 and the accompanying online election form will be allowed to be submitted prior to that date, after which the account will be opened on July 4 or whenever the government gets the new accounts online. There's currently no deadline to make the elections to open the account or receive the pilot contribution, but parents will need to be aware of the need to elect into opening a TA and/or receiving the pilot contribution if they want to receive the "free" $1,000 into their child's account.

Like qualified general contributions, the TA pilot program contribution won't count toward the $5,000 limit for direct and employer contributions, so opting into the pilot program won't affect the TA beneficiary's ability to receive contributions from other sources.

Reversion to Standard IRA Rules At Age 18

For the most part, the unique rules for TAs as explained above apply only in the years between the beneficiary's birth and the year in which they turn 17. Starting in the year the beneficiary turns 18, the TA becomes, for most practical purposes, a standard traditional IRA.

That means that starting in the year of the beneficiary's 18th birthday, the contribution limit for standard IRAs applies ($7,500 in 2026) rather than the one for TAs ($5,000 in 2026). The beneficiary also must have earned income to be able to contribute. Finally, only direct contributions are allowed to the TA at this point, not employer or qualified general contributions.

Nerd Note:

If a TA beneficiary age 17 or younger has earned income of their own, they can contribute to both a TA and an IRA. And contributions to one type of account don't affect the amount that can be contributed to the other, meaning that in 2026, a beneficiary with at least $7,500 in earned income can contribute $5,000 to a TA and $7,500 to an IRA.

Tax Treatment Of Contributions And Withdrawals

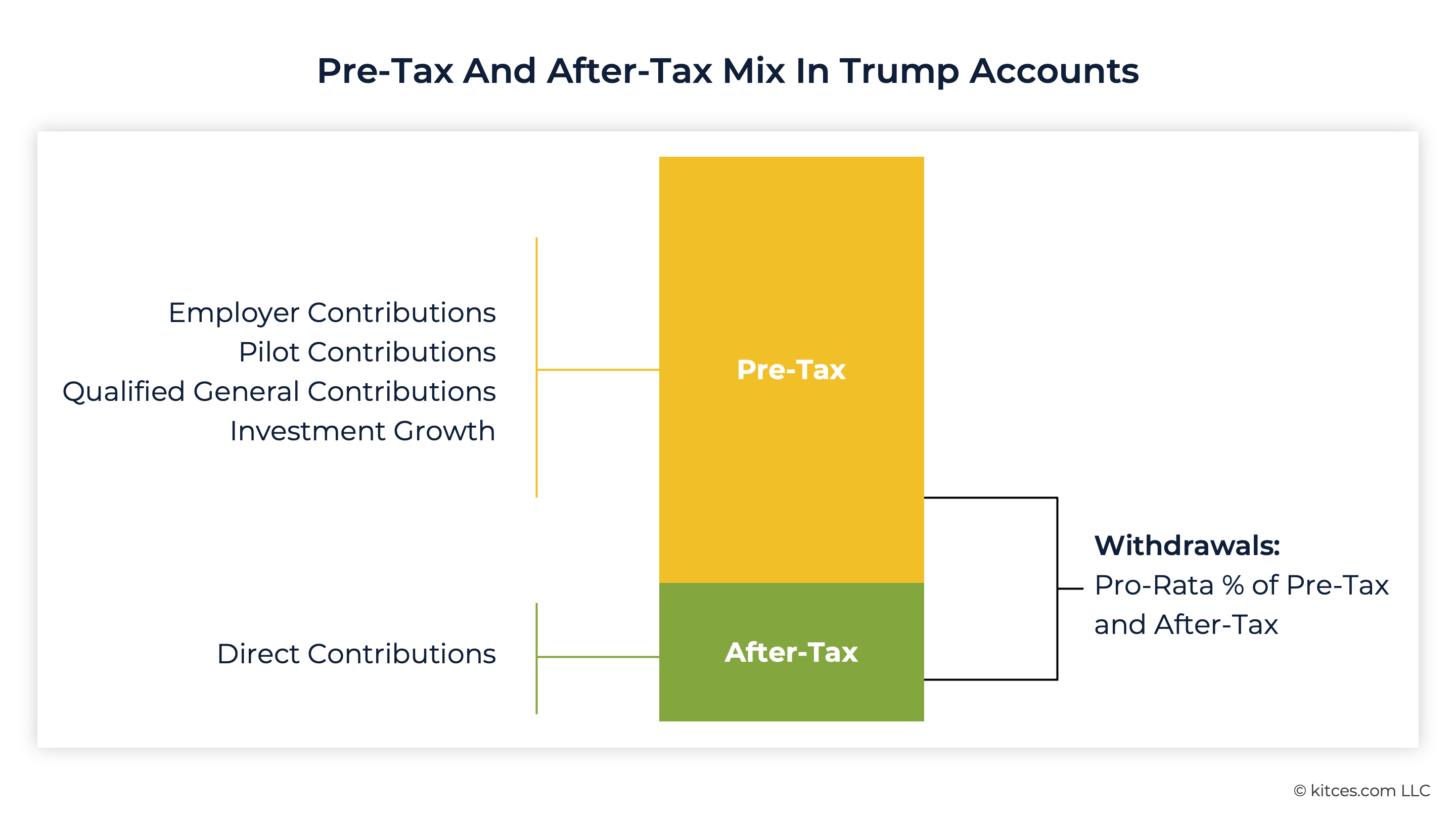

Like traditional IRAs, TAs can contain a mix of both pre-tax and after-tax dollars. Direct contributions, which are non-deductible, are treated as after-tax dollars (i.e., basis) within the TA. Employer contributions, qualified general contributions, and the $1,000 pilot program contribution – all of which are excluded from gross income when received – are pre-tax. Additionally, any growth or investment income beyond the initial contributions, which is tax-deferred until withdrawal, is pre-tax within the account.

Withdrawals from a TA aren't allowed until the year in which the account beneficiary turns 18. However, at that point, the distribution rules are the same as those for traditional IRAs. Each distribution from the TA is partially or fully taxable, and distributions before age 59 ½ come with an additional 10% penalty tax unless they meet an exception under IRC Sec. 72(t) (e.g., for higher education expenses, for up to $10,000 in first-time homebuyer expenses, or as part of a series of annuity payments for at least 5 years or until the owner reaches age 59 1/2). TAs can also be rolled over to a standard IRA starting in the year the beneficiary turns 18, and can also be converted to a Roth IRA at that point (which could have significant planning implications, as will be explored below).

Upon withdrawal, TAs follow the same tax rules as traditional IRAs with basis: Each distribution is treated as part return of basis (which is tax-free) and part pre-tax (which is taxable as ordinary income). The tax-free portion is calculated as a pro rata amount based on the proportion of after-tax dollars in the account to the total account size.

Example: Suzie has a TA with a total account value of $100,000, which her parents contributed a total of $25,000 to in after-tax direct contributions when she was a child. The $25,000, then, represents Suzie's basis in the TA.

Suzie takes a $10,000 distribution from the TA. According to the pro rata rule, the non-taxable portion of the distribution equals the proportion of after-tax dollars in the TA to the total account size, or $25,000 ÷ $100,000 = 25%. Therefore, 25% × $10,000 = $2,500 of the distribution will be non-taxable, and the remaining $10,000 − $2,500 = $7,500 will be taxed as ordinary income.

Basis Tracking Requirements

TA beneficiaries, and anyone who controls the account on their behalf (e.g., parents), will presumably be responsible for tracking which dollars within the TA are pre-tax and which are after-tax. This will likely be done using Form 8606 (or a modified version thereof), which is used for tracking basis within standard IRAs.

This is significant because it's extremely common for individuals to lose track of the basis in their own IRAs, since it's often forgotten that Form 8606 must be filed every year in which there is basis in an IRA, not just in the year an after-tax contribution is made. Add in the fact that control of the TA (and the accompanying tax reporting responsibility) will inevitably change hands from the TA beneficiary's parent or guardian to the beneficiary themselves after they reach the age of majority (typically 18 or 21, depending on the state), as well as the potential need for the beneficiary to track their basis for over 40 years between the dates of their last TA contribution (at age 17) and their first penalty-free withdrawal (at age 59 ½), and it's easy to imagine the basis of many TAs being 'misplaced' at some point.

Without a Form 8606 on file to substantiate the basis in the TA, the IRS's assumption is that the entire distribution is taxable. Meaning that many future TA beneficiaries will be taxed on their full distributions – even though they consist partly of what should be considered after-tax dollars – unless the TA beneficiaries (and their parents before them) are extremely diligent about filing Form 8606 each year.

However, the silver lining (if you can call it that) is that after many years of tax-deferred growth, the proportion of after-tax dollars in the account will be fairly miniscule compared to the pre-tax growth portion, making the vast majority of each distribution taxable even if the basis is properly tracked over the years. So, if the TA owner does keep the account going until retirement, it may not ultimately matter much whether or not they filed Form 8606 over the years when it comes to the actual taxable amount of their distributions.

The Tax Impact Of TAs On Saving For Children

Having covered the "what" of TAs, it's time to talk about the "how", and, more importantly, the "why". Do TAs' tax incentives make them a viable alternative to the other types of savings vehicles that are already available?

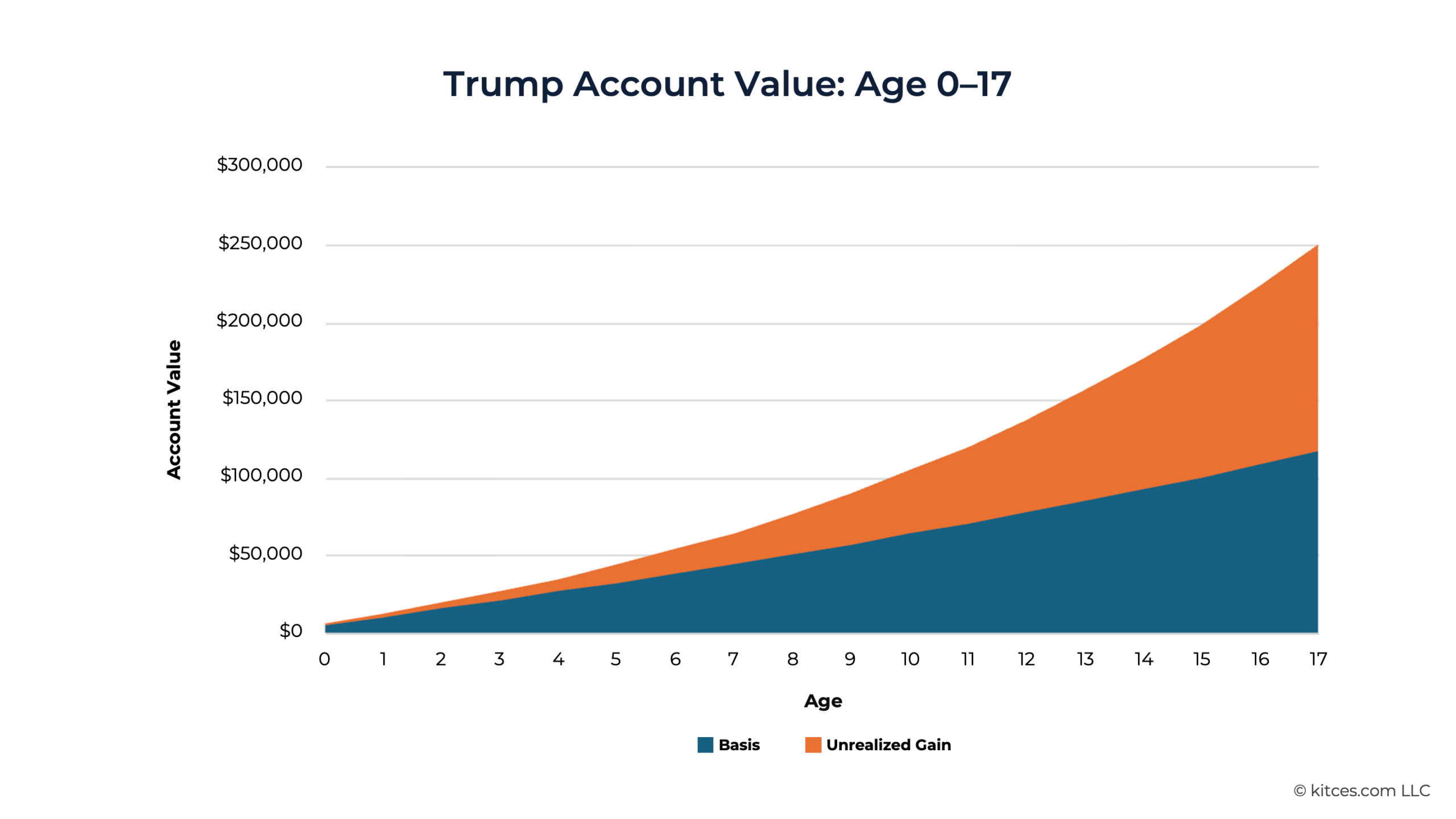

Let's start with how much one could actually expect to be able to save in a TA. Imagine a baby named Tara, born in 2026, receives a $1,000 pilot contribution from the U.S. government to kick off her TA savings. Tara's parents make the maximum direct contribution to her TA each year, starting at $5,000 in 2026 (when she's born) and, assuming a 3%/year inflation rate, topping out at $8,200 in 2043 (the year she turns 17, after which she can no longer make contributions under the TA rules).

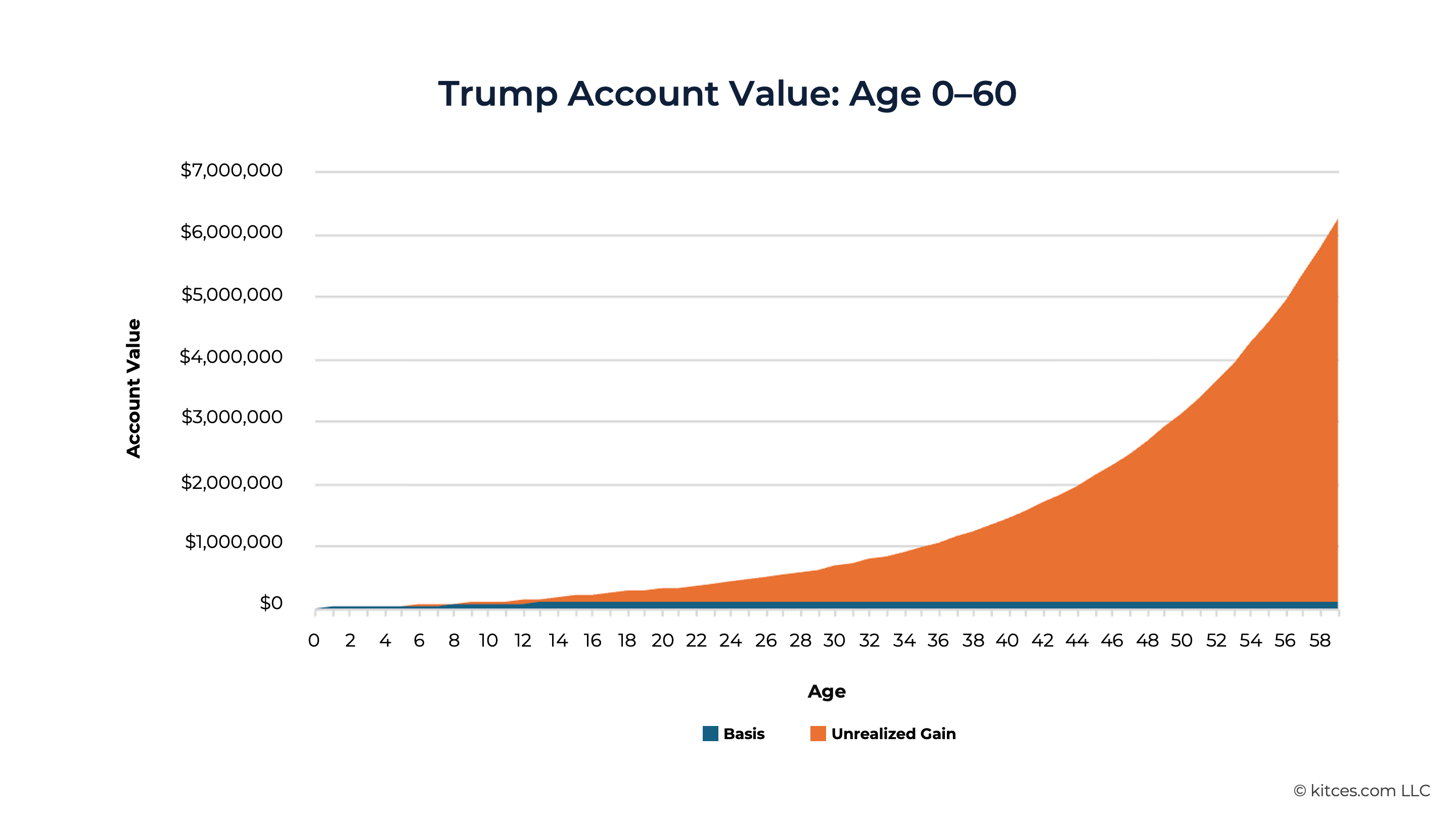

Assuming an 8% per year growth rate, the value of Tara's TA on her 18th birthday will be $250,069. Of that, $116,300 consists of basis – i.e., the total amount her parents contributed over the years – while the remaining $133,679 is growth on the account. (This assumes there were no additional employer or qualified general contributions.)

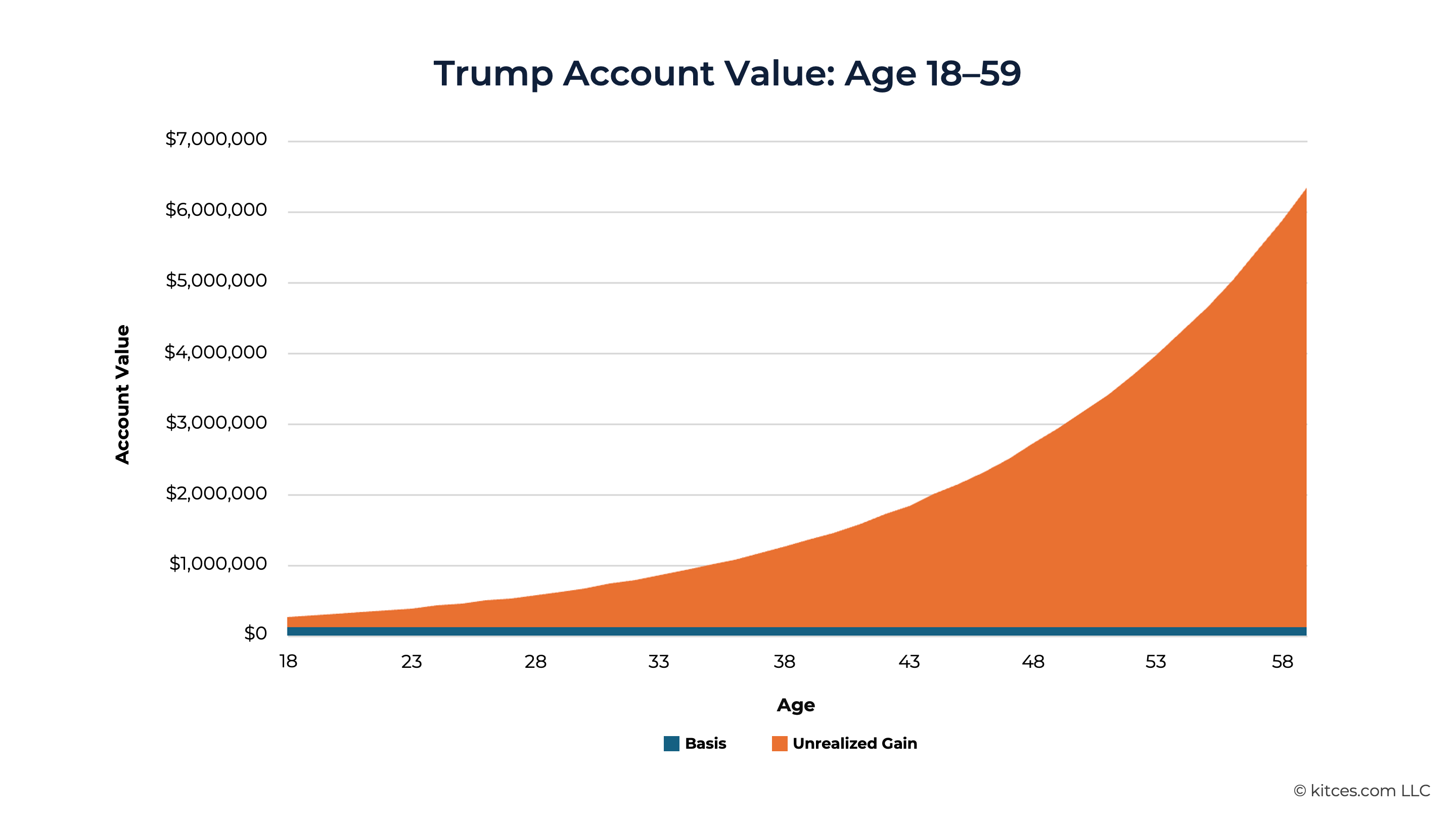

If Tara makes no more contributions starting in the year she turns 18, the $116,300 of basis will remain fixed until she starts taking distributions on the account, while the $133,679 of growth – plus any additional growth after that point – will be taxable at Tara's marginal ordinary income rate when it's distributed.

This matters because, if Tara simply allows the account to grow at an 8% rate until 2085 (when she turns 59 ½ and can take penalty-free withdrawals), the TA's value at that point will be $6,336,611. Of that amount, $6,220,311 represents tax-deferred growth, making every withdrawal that Tara makes after that point over 98% taxable. (And if Tara ever loses track of her basis in the account, every distribution would become 100% taxable.)

This may be the biggest downside to TAs. Although many decades of tax-deferred compounding may allow the accounts to grow to an eye-popping size, all that growth must eventually be taxed. And in an age when many financial advisors plead with their clients who own $1 million-plus traditional IRAs and 401(k) accounts to move money out of those accounts before those dollars are forced out at higher tax rates due to either RMDs (during the owner's lifetime) or the SECURE Act's 10-year rule (after the owner's death), how many advisors would recommend young families to save to an account that could eventually lead to a $6 million-plus pre-tax balance? Even when adjusting that amount down to 2026 dollars with a 3% inflation rate, a $6,336,611 balance in 2043 equates to $1,107,799 today. Or to put it more plainly, making maximum TA contributions might just create the same tax planning headaches for one's children in the future as are faced by $1 million-plus traditional IRA owners today.

That fact alone might give advisors pause in recommending that clients go all-in on opening and funding TAs for their kids. The accounts would compound pre-tax over such a long time that they'd almost inevitably become the source of tax planning issues absent any legislation that changes their tax treatment. And while Roth conversions are an option to reduce or eliminate the pre-tax growth problem, those have their own issues, as will be explored in more depth below.

How Taxable Custodial Accounts Beat TAs For Tax Benefits And Flexibility

TAs aren't the only type of accounts available for parents to save on their children's behalf. Several other options already exist, most notably 529 college savings plans and taxable custodial accounts.

Much of the media coverage so far has focused on TAs versus 529 plans, since 529 plans are likely the most popular type of account used to save for kids today. However, the comparison between the two is somewhat apples-to-oranges: While 529 plans are generally meant for college and graduate school expenses (and increasingly for K-12 costs and postsecondary credentials in the wake of OBBBA's expansion of 529-eligible expenses) and thus designed to be exhausted within 20–25 years of being opened, TAs are primarily geared toward retirement, and have a time horizon of 60+ years. So, if parents must choose between one or the other, the decision mainly comes down to whether they primarily want to contribute to their child's education or to help fund their child's retirement.

That said, 529 plans have the ability to roll over a lifetime maximum of $35,000 tax-free into a Roth IRA. While both TA and 529 plan contributions are made after-tax, and both can be rolled over (at least partially) to a Roth IRA, the 529-to-Roth rollover can be made entirely tax-free, while converting a TA to Roth entails a tax on the entire pre-tax portion of the account. So, it could still be better to fund a 529 plan at least to the extent that it's possible to max out the $35,000 lifetime 529-to-Roth rollover limit before considering contributing to a Trump account.

But there's been less attention paid to how Trump accounts compare to UGMA or UTMA custodial accounts – that is, standard taxable brokerage accounts owned by a minor child and controlled by an adult (usually by a parent or grandparent) on their behalf. Which is unfortunate, because even if they lack the potential tax-free treatment of 529 plan funds, custodial accounts have features that can make them a superior option to TAs despite their taxable nature.

Custodial Account Rules And The "Kiddie Tax" For Minors

UGMA and UTMA custodial accounts are taxable brokerage accounts for minor children that are managed by an adult custodian until the child reaches their state's age of majority, at which point the child takes ownership and full control of the account. There is no contribution limit for custodial accounts, though the annual gift tax exemption ($19,000 in 2026) applies to contributions from a third party like a parent or grandparent. For tax purposes, UGMA and UTMA accounts are treated like standard taxable brokerage accounts, with all income and capital gains being taxable income for the child in the year it's incurred.

The standard criticism of taxable accounts (including custodial accounts) is that they incur "tax drag" because their investment income is taxed each year. As the thinking goes, the ongoing taxation of dividends and capital gains (and the need to remove funds from, or reduce contributions into, the portfolio to pay those taxes) hampers the portfolio's ability to grow, with the detrimental effects being magnified when compounded over years and decades. Which is why tax-deferred accounts like IRAs and TAs exist in the first place: Being able to defer taxes on investment growth and income means that the entire portfolio can stay invested for the long term and compound to a much higher value than a taxable account where funds need to be constantly taken out to pay the IRS's share of the income.

However, while tax drag can be a sizeable downside to taxable accounts for some investors – namely those in high capital gains tax brackets and with high-income investments – there are times when the rules for taxable accounts actually give them an advantage over their tax-deferred counterparts. And for minor children, the taxation of UGMA and UTMA accounts, which are generally subject to the "Kiddie Tax" rules on investment income, can provide a powerful method of avoiding paying tax on investment income – both today and after the custodial account owner becomes an adult.

The kiddie tax is a special set of rules that apply to unearned income received by children who are either (1) age 17 or younger; (2) age 18 and don't have enough earned income to provide at least half of their own support; or (2) age 19 to 23, are a full-time student, and don't have enough earned income to provide at least half their support. If any of those conditions are true, any unearned income the child receives (including interest, dividends, capital gains, rents, and retirement plan distributions) is taxed in three separate buckets:

- The first bucket of unearned income (up to $1,350 in 2026) is tax-free;

- The second bucket (the next $1,350 in 2026) is taxed at the child's marginal tax rate; and

- The third bucket of any unearned income beyond $2,700 is taxed at the child's parents' marginal rate.

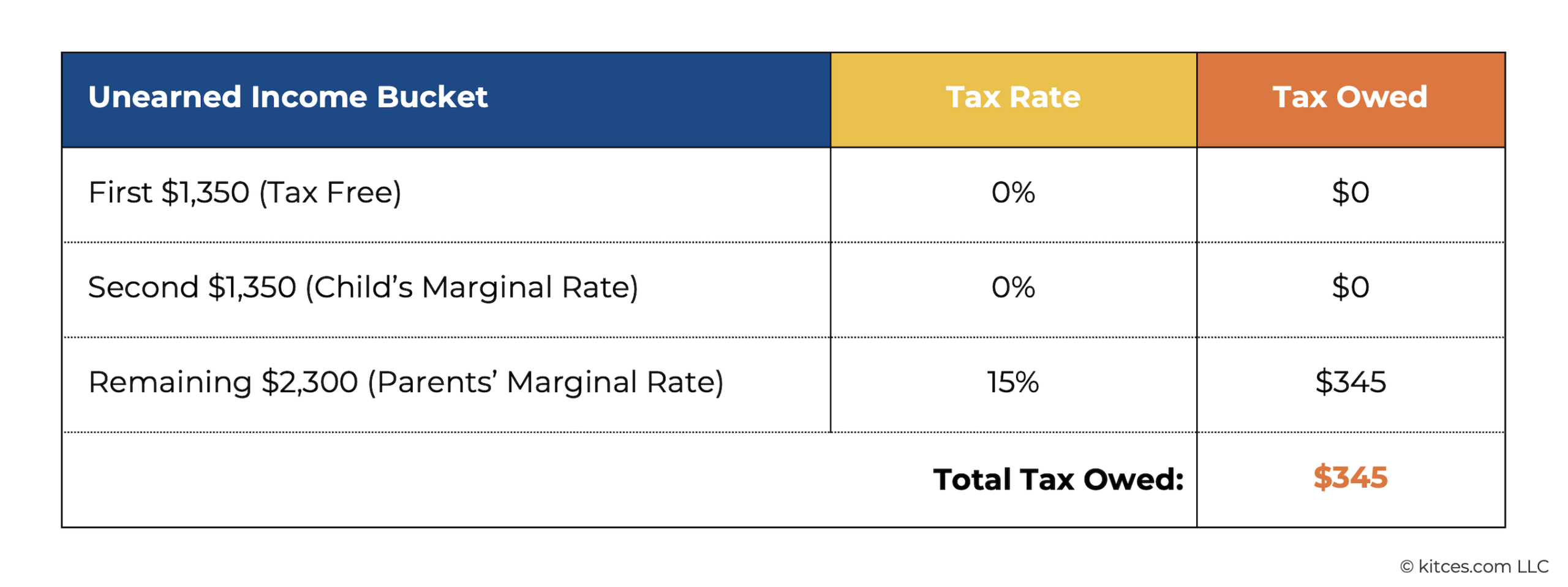

Example: Meghan is the 15-year-old daughter of Mark and Alana. She owns a custodial account that generates $5,000 of qualified dividends and long-term capital gains in 2026. Meghan has no other taxable income this year, and her parents are in the 15% Federal income tax bracket for qualified dividends and capital gains.

Under the kiddie tax rules, the first $1,350 of unearned income from the account is tax-free. The next $1,350 is taxed at her marginal tax rate for qualified dividends and capital gains, which is 0% for Meghan as a single filer with taxable income of less than $49,450. The rest of the income in the account, or $5,000 − $2,700 = $2,300, is taxed at her parents' marginal tax rate of 15%. As shown below, the total tax that Meghan owes on her $5,000 of unearned income is ($1,350 × 0%) + ($1,350 × 0%) + ($2,300 × 15%) = $345.

The kiddie tax rules are meant to disincentivize high-earning parents from shifting large amounts of income-producing assets to their minor children in order to take advantage of their relatively low marginal tax rates: For example, if a parent gifted their child an investment that generates $100,000 of income per year, only a fairly negligible amount of that income – $2,700 – would be taxed at a rate lower than the parents' own marginal rate.

But for smaller investment balances that produce less taxable income, the kiddie tax's structure actually provides an advantage: It creates an effective 0% tax bracket for the first $2,700 of dividend and capital gains income. And that 0% bracket can be used to "harvest" capital gains at a 0% tax rate for as long as the kiddie tax rules are in effect.

Example: Diana is a 10-year-old child whose parents have contributed to a taxable custodial account for her benefit. This year, the account's balance is $25,000, and it generates $500 of qualified dividend income.

Since the $500 of dividend income is less than the $2,700 kiddie tax threshold, it is tax-free to Diana. Additionally, Diana's parents could realize another $2,200 in capital gains, bringing her total unearned income to $2,700 – all of which would be tax-free.

Why harvest capital gains? As with 'adult' taxable accounts, harvesting gains in a custodial account increases the cost basis of the account's investments, leaving fewer unrealized capital gains that could potentially be taxed at a higher rate when the child is no longer a dependent subject to the kiddie tax rules. For instance, if Diana's parents in the example above don't harvest the extra $2,200 in gains under the kiddie tax rules today, she may end up realizing them later in life when she is in the 15% capital gains bracket, and would owe $2,200 × 15% = $330 on the sale rather than $0.

Parents who harvest capital gains in their kids' taxable accounts up to the kiddie tax threshold can potentially save thousands of dollars of future taxes for their kids. For example, for a child born in 2003 (when the kiddie tax threshold was $1,500), harvesting the maximum amount of capital gains each year from 2003 to 2026 (the child's age-23 year, the final year that the kiddie tax rules could apply) would result in $49,300 in additional basis – which at a 15% tax rate equates to $7,395 in tax savings.

The harvesting can be as simple as selling near the end of the year to realize gains up to the kiddie tax threshold (minus dividends and any other capital gains realized during the year), and then immediately buying them back – because unlike the process of harvesting capital losses, harvesting capital gains does not trigger the wash sale rule requiring the seller to wait 30 days before buying back the original investments.

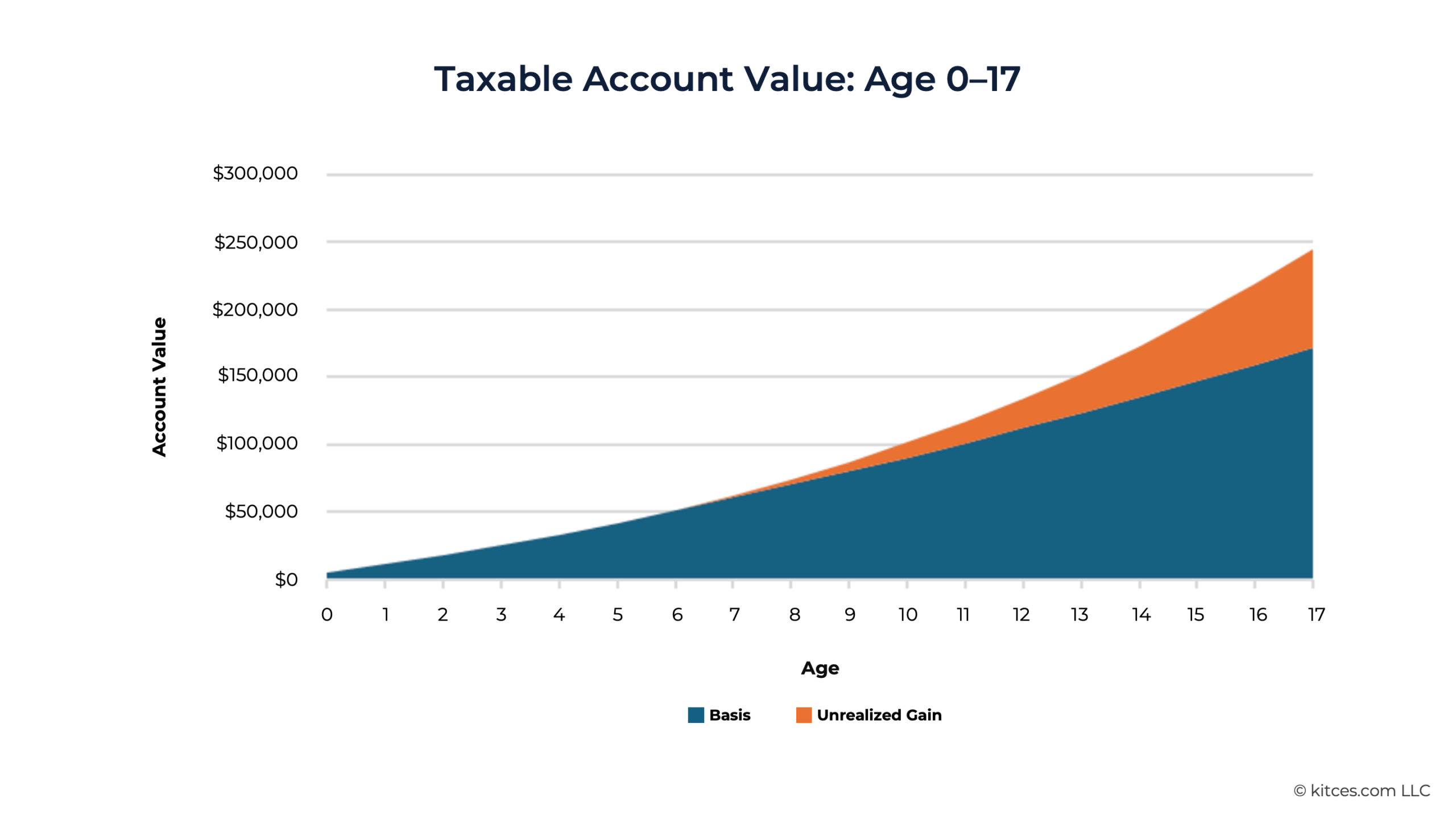

The upshot of the kiddie tax rules is that, when gifting moderate amounts of assets to children via a taxable custodial account, there may be little to no tax drag at all, since income generated by the assets is tax-free up to the kiddie tax threshold. And the current $2,700 threshold is high enough that, if invested in relatively tax-efficient vehicles like ETFs, the account would need to reach a significant size to generate enough income to be taxed at the parents' rates. For example, at the S&P 500's current dividend yield of 1.17% as of this writing, an account invested in an S&P 500 ETF would need a balance of $2,700 ÷ .0117% = $230,769 to trigger the kiddie tax from dividends alone. And with the room left over beneath the threshold, the managers of custodial accounts can harvest gains up to the combined $2,700 limit to minimize the amount of unrealized gains that remain in the account once the child is no longer a dependent.

This is a key advantage for taxable custodial accounts over the new Trump account. Because TAs remain tax-deferred and allow no withdrawals before the beneficiary's age-18 year, all growth in the account effectively remains "unharvested". Or put differently, after several years of investing, a TA's balance may consist of much more growth – and much less basis – than a taxable account where gains were harvested up to the kiddie tax threshold each year. And the growth that's in the TA, once it's distributed, is taxed at ordinary income rates (of up to 37%) rather than the capital gains rates (of up to 23.8%) that the taxable account is subject to. So, the TA will end up with more future taxable income than the taxable account, and that income will be taxed at higher rates!

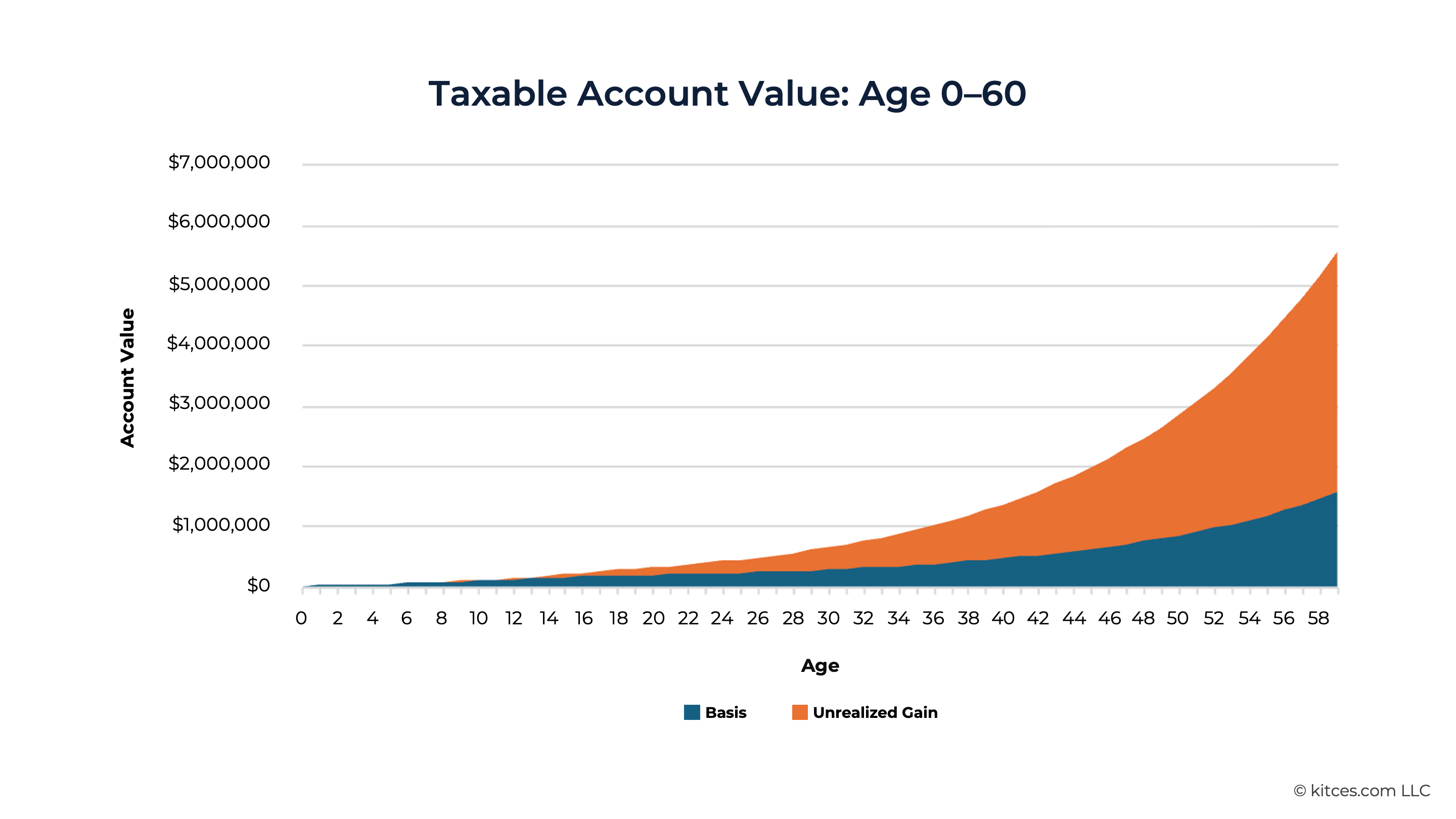

The taxable account's advantage can be illustrated by comparing an annual maximum direct contribution to a TA from birth to age 17 to making the same contributions to a taxable account. Assume the accounts are invested the same way, at an average growth rate of 8% (consisting of 2% dividends and 6% capital gains), and capital gains in the taxable account are harvested up to the amount of the kiddie tax threshold each year (minus dividends received). By the end of the age-17 year, the taxable account would be worth $246,059, comprised of $172,177 of basis and $73,881 of unrealized gain.

The Trump account, on the other hand, has a value at age 17 of $246,073 – but because all of its growth remains tax-deferred, it contains only $116,300 of basis and $129,773 of growth.

On an after-tax basis, if we assume the unrealized gains in the taxable account are taxed at 15% and the growth in the TA is taxed at 22%, the taxable account is worth $246,059 − (15% × $73,881) = $234,977, while the TA is worth $246,073 − (22% × $129,773) = $217,523. In after-tax terms, then, the custodial account has the advantage over the TA, even if the two account types are nearly equal in pre-tax value.

However, it isn't quite fair to compare the TA and taxable account values at age 18, since the TA is explicitly meant to be a retirement account that isn't touched until at least age 59 ½. So, we can also compare their projected values at age 59 ½, at which point distributions from the TA can be made penalty-free. Assume that there are no more contributions to either account starting at age 18, and that it continues to generate 2% of its value in qualified dividends each year, which are taxed at a 15% capital gains rate in the custodial account and paid out of the account balance. Additionally, we'll assume that the account is invested in ETFs that generate no capital gains or losses realized after age 22 (after which the kiddie tax rules no longer apply).

The taxable account's value at age 60 would be $5,547,509, of which $1,529,177 is basis and $3,998,331 is unrealized capital gain.

The TA, meanwhile, would be worth $6,235,354, of which just $116,300 is basis (i.e., the same amount as when contributions stopped at age 18), while $6,119,054 is tax-deferred growth.

Again, assuming a 15% tax rate on capital gains in the taxable account and a 22% rate on the TA, the taxable account at age 60 is worth $5,547,509 − (15% × $3,998,331) = $4,947,859 on an after-tax basis. The TA at the same age is worth $6,235,354 − (22% × $6,619,054) = $4,779,153. In other words, despite the 'tax drag' incurred by the taxable account from incurring taxable dividends over time, resulting in a lower pre-tax value, the taxable account is still worth more than the TA on an after-tax basis.

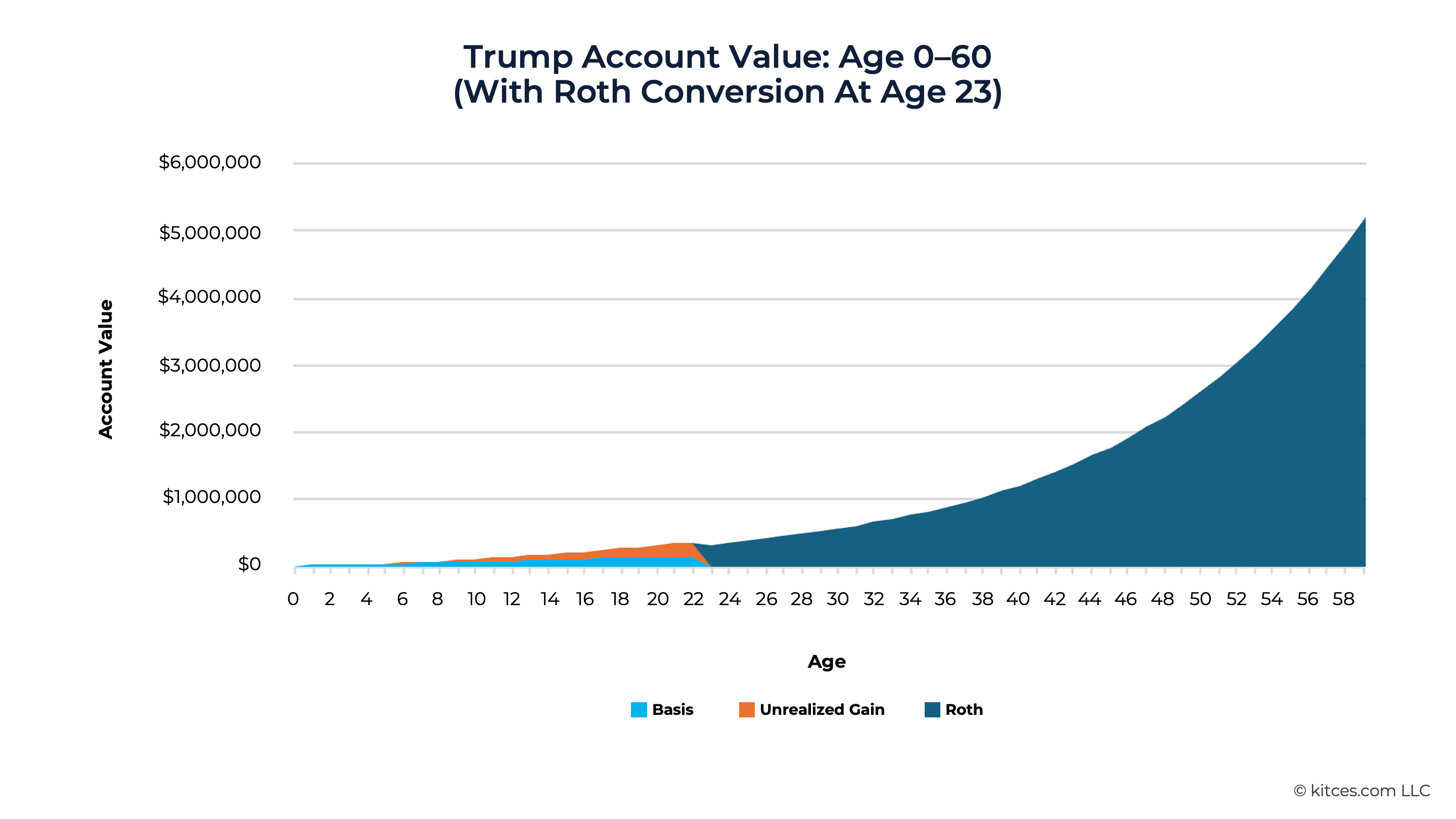

The Impact Of Roth Conversions

There's one additional consideration when comparing TAs to taxable custodial accounts, and that's the ability to convert TAs to Roth. In its initial guidance on Trump accounts, the IRS confirmed that starting in the year a TA beneficiary turns 18, the accounts become subject to most of the rules governing standard IRAs under IRC Sec. 408, including the ability to convert some or all of the TA's assets to Roth. Taxable accounts, in comparison, can't be converted to Roth: A taxable account owner could choose to use funds from a taxable account to make Roth contributions, but those contributions would be subject to the annual contribution limit ($7,500 in 2026) and income restrictions (with contributions phased out for single filers with $150,000 to $153,000 of AGI and joint filers with $236,000 to $242,000 of AGI).

At first glance, the ability to make Roth conversions from TAs as soon as the beneficiary reaches the year of their 18th birthday may seem like an enormous tax planning opportunity. The early years of adulthood – when an individual might perhaps be finishing high school, going to college, or getting started on a career – are likely to be among the lowest-tax years of someone's life. Unless they get started on a lucrative career immediately after graduating from high school, they'll often have low or even no income in the first few years after turning 18. Which could allow them to convert most or all of their TA to Roth during those years that they're in the lowest income tax brackets, and never owe tax on those funds again.

Roth Conversions For Dependents: The "Kiddie Tax" Strikes Back

However, there's a catch that could make it much less appealing to convert pre-tax TA dollars to Roth at the earliest possible time. That's because, just like dividends and capital gains from taxable accounts for young adults who are still dependents of their parents, the "kiddie tax" rules apply to the taxable part of any IRA distribution, including the taxable portion of a Roth conversion.

As described above, under the kiddie tax rules, any unearned income for a dependent child is treated as tax-free up to the first $1,350 (in 2026), while the next $1,350 is taxed at the child's marginal tax rate. Any additional unearned income beyond the first $2,700 (in 2026 dollars) is then taxed at the parents' marginal tax rate. And unlike dividends and capital gains, which are taxed at capital gains rates, any TA Roth conversions would be taxed at ordinary income rates, resulting in a much greater impact for children of parents in the highest tax brackets – which top out at 37% for ordinary income rather than 23.8% for capital gains.

Example: Eleanor is born in 2026, and her parents open a TA and contribute on her behalf throughout her childhood. Eleanor goes to college at age 18 and has no income for the next four years, remaining a dependent on her parents' tax return.

Imagining that the kiddie tax thresholds are the same today as they are when Eleanor goes to college, her first $1,350 of unearned income is tax-free, while the next $1,350 is taxed at her own marginal rate, and the remainder is taxed at her parents' marginal rate. If Eleanor is in the 10% tax bracket (since she has no other income) and her parents are in the highest (37%) tax bracket, then the first $2,700 of pre-tax TA dollars could be converted to Roth at a 5% effective marginal rate (i.e., the first $1,350 is taxed at 0% and the next $1,350 is taxed at 10%) – but any additional converted dollars would be taxed at 37%.

It would be difficult for young adults with little or no income of their own to convert large amounts of pre-tax TA dollars to Roth in the lowest tax brackets, since if they're still full-time students, they're also likely to be claimed as dependents on their parents' tax returns and thus subject to the kiddie tax rules. Most TA account beneficiaries would need to wait until they're out of school and earning income of their own to convert most of their TA funds to Roth at their own marginal tax rates, which means that instead of converting the funds at the lowest 0% or 10% tax brackets, they would probably be forced to convert them at 22% or higher – making the ability to convert to Roth much less attractive.

Paying The Tax On Roth Conversions

Even after they stop being a dependent, a young adult in the first years of their working career is likely to have relatively low income compared to their future peak earning years. Which could still make it appealing to convert TA dollars to Roth in their early working years, and then allow those funds to grow tax-free for the rest of their lives.

But it's also worth remembering that the beneficiary will still need to pay the tax on the Roth conversion, and it's unlikely that at that point in their career they'll have funds outside the TA itself to pay with. So, they'll need to use TA funds to pay the tax on the conversion, with those funds being taxable themselves plus a 10% early withdrawal tax, which further reduces the appeal of the Roth conversion.

For example, in the earlier comparison between TAs and taxable accounts, the pre-tax value of the TA at the end of the beneficiary's age-23 year is $390,486, including $274,186 in growth and $116,300 in basis. Let's assume that at age 24, that amount is converted to Roth at a 22% marginal tax rate (in reality, it would take several years of conversions to do this while staying within the 22% Federal bracket, but for simplicity, we'll pretend it can all be done in one year). The tax on the conversion itself would be 22% × $274,186 = $60,321. But if that tax needs to be paid from the TA, it will be subject to a 10% early withdrawal penalty on the taxable portion of the withdrawal, or 10% × $60,321 × ($274,186 ÷ $390,486) = $4,236, meaning that only $290,486 − $60,321 − $4,236 = $325,929 would actually end up in the Roth IRA.

If the net amount that's left in the Roth grows at an 8% rate until age 60, the account will be worth $5,204,497 (which is the same as its after-tax value since Roth funds can be withdrawn tax-free after age 59 ½)

Recall from a previous example that the value of the pre-tax account at age 60 is $5,547,509 on a pre-tax basis and $4,947,859 after tax.

On an after-tax basis, then, the TA after making Roth conversions has the advantage, with $256,638 more than the taxable account – but recall that that number is in 2086 dollars, 60 years in the future. In 2026 dollars, assuming a 3% inflation rate, that equates to a $43,560 advantage for the TA over the taxable account.

So, while the TA, with its ability to make Roth conversions, may be a good way to maximize the amount of Roth funds that a beneficiary will have available at retirement age, the real economic difference between the Roth-converted TA and a plain taxable account isn't as stark as one might imagine. After accounting for the tax on the conversion, the Roth's ending value could end up being either slightly more or slightly less than the taxable account, depending on the fluctuation of tax rates over time.

Some parents might choose to help their kids pay the tax on the conversion (either by gifting the funds outright or loaning them at a low interest rate), to allow the Roth funds to stay in the account to grow tax-free over time. This would tilt the math more in favor of the TA-plus-Roth-conversion strategy; however, not all parents might be willing or able to contribute the funds to pay their kids' taxes, and parents who opt for a taxable custodial account could likewise gift their kids additional funds to offset the tax impact of their investment income.

It's also worth noting that taxable accounts are far more flexible than TAs or IRAs, including Roth IRAs. The ability to take penalty-free distributions from a taxable account before age 59 ½ opens them up for purposes such as buying a home, starting a business, and any other need that the owner may have before approaching retirement age. Plus, if the account owner passes away before using all of their funds, the tax rules heavily favor the taxable account: All of the unrealized gains in the taxable account will receive a step-up in basis at the owner's death, while the TA would follow the SECURE Act's byzantine inherited IRA rules, subjecting most non-spouse beneficiaries to the 10-year rule.

And there are other potential considerations to keep in mind. For instance, a TA will likely be considered a retirement account for the purposes of financial aid calculations, and thus would be excluded from the child's assets listed on the FAFSA. In contrast, assets in a UTMA or UGMA custodial account are listed as the child's assets and could harm their ability to qualify for financial aid. Thus, if there's a possibility of qualifying for need-based financial aid, it's better to avoid UTMA or UGMA accounts.

Finally, with some opportunities existing to claim 'free' money within the TA that might not be available elsewhere, such as with the $1,000 Federal pilot contribution and qualified general contributions like the Dells' $250 donation, it might still make sense to open a TA even if there are no plans to make any direct contributions.

But the bottom line is that while the funds that parents put into TAs on their kids' behalf may grow to an impressive size, in reality, it's the fact of the saving and investing itself that matters far more than the particular tax characteristics of the TA. Children of parents who save to a 529 plan or a regular taxable custodial account can end up with just as much, or even more, on an after-tax basis, and with the possibility of more flexibility to use the funds before retirement to boot. The key is simply for parents to start setting the money aside at an early age to begin with, no matter which vehicle they decide to save within.

Leave a Reply