Executive Summary

Financial advisors at RIAs have a fiduciary obligation to their clients, which includes both a Duty of Loyalty (to avoid – or at least disclose and take steps to mitigate – any conflicts of interest) and a Duty of Care (to act with prudence when making investment recommendations, considering both their investment opportunity and benefits along with the associated costs). However, while certain costs (e.g., fund expense ratios or ticket charges on trades) are relatively transparent, RIA custodians also earn revenue in various ways from client portfolios in exchange for the custodian's services. Which means RIAs that place clients at a particular RIA custodial platform also have a fiduciary obligation to ensure that their clients are paying reasonable expenses to the platform in exchange for the services they receive. That said, when it comes to RIA custodians, there is no explicit fee for services – nor really any way to determine the total costs clients actually pay (i.e., that their RIA custodian earns) for custodial-related services – making it difficult for firms to determine whether their current custodial relationships are truly aligned with their fiduciary obligation to their clients.

Notably, RIAs aren't necessarily required to choose the lowest-cost custodial option for their clients. Nonetheless, if an RIA did choose a more expensive one, the firm would, at a minimum, have a fiduciary obligation to justify why that option was chosen and how it would benefit the client (e.g., a particular custodian might offer superior technology to execute trades and better service to resolve client issues). Though, given the lack of price transparency amongst custodians, such a calculation is again nearly impossible to make!

With the current RIA custody model creating challenges for advisory firms to fulfill their fiduciary responsibilities to their clients – and putting their interests at odds with those of the custodians they work with (with a firm trying to minimize custodian-related client costs and the custodian having an interest in generating more revenue from each RIA client) – both RIA firms and custodians have an interest in finding an alternative.

One possible option would be for the RIA custodian to charge a basis-point fee to each client of RIAs on its platform, equal to the average fees they're earning under the current model (so the custodian continues to earn the revenue it needs to provide its services), and then apply a credit to the client's statement for any other revenue the custodian is earning. In many cases, this might fully offset the custodial fee anyway, but it would be done at the client's discretion as to how they wish to pay! In turn, custodians would be incentivized to better 'stock the shelves' of their custodial platform with unique offerings (e.g., highest-yielding cash sweeps, lower-cost investment products) to attract advisors and their clients to the platform to pay the fee (and thus grow their own assets).

While the concept of such an 'upside-down' fiduciary model for RIA custody is relatively straightforward to re-align the interests of the custodian, the advisor, and their client, doing so would come with non-trivial complexities and questions – not only in terms of systems but also in determining fairness to RIAs and their clients. For example, a custodian would have to determine whether the statement credit would be allocated across all clients on their platform at the client, account, or individual holding level. Also, such a move could lead to uncomfortable conversations for advisors (e.g., if they choose a more expensive custodian that provides them with practice management support or client referrals, which benefit the advisory firm but don't actually benefit the client that incurred the cost).

Though, arguably the biggest challenge of instituting a basis-point fee and statement credit system is behavioral. Simply put, clients (and their advisors) aren't used to paying an outright fee for custody. And when something has been provided for 'free' for so long, any fee – no matter how reasonable – can induce sticker shock (even if much, or even all, of the fee is being rebated through the statement credits)! Though notably, the entire evolution of the RIA movement for the past 20 years has been the transition from opaque commissions (on investment products) to transparent advisory fees, which consumers have ultimately come to prefer because of the better alignment with their advisor… suggesting that, in the long run, custodians stand to benefit from a more fiduciary pricing model for RIA custody in the same manner that RIAs themselves have benefited in the marketplace.

Ultimately, the key point is that the current RIA custody model presents fiduciary challenges for advisors, who have no feasible way to compare the costs for their clients of different custodians they might work with to ensure clients are receiving benefits commensurate with their cost (as custodial revenue yield, and thus pricing, can vary significantly from one platform to another). Which suggests that an alternative approach – pairing a clear basis-point fee for the client with statement credits for revenue generated by their use of custodial services – not only offers greater transparency in the costs for custodial services but also better aligns the interests of clients, advisors, and the custodians they work with. And, in the end, that alignment would allow advisors to more effectively fulfill their fiduciary obligations to clients!

One of the core distinctions between RIAs and the brokerage or insurance channels of the industry is the fiduciary duty that these firms have toward their clients. One area where this fiduciary duty manifests itself is in portfolio management, where advisors have a responsibility to seek out best execution on trades, incur (only) reasonable trading fees, and ensure that investment vehicles implemented for clients either minimize costs (i.e., expense ratios) or at least provide value commensurate with any additional costs that clients might have to pay. With at least the latter two categories being relatively transparent.

Notably, though, costs that clients incur to implement their investment portfolios are not exclusively a matter of expense ratios on mutual funds and ETFs or ticket charges on trades. Investment platforms themselves, from brokerage firms to RIA custodians, also earn revenue in various ways from client portfolios for their services. Which means RIAs that place clients at a particular RIA custodial platform also have a fiduciary obligation to ensure that their clients are paying reasonable expenses to the platform in exchange for the services they receive.

However, when it comes to RIA custodians, there is only opacity in terms of the costs clients actually pay for custodial-related services, making it difficult for firms to determine whether their current custodial relationships are aligned with their fiduciary obligation to their clients. Simply put, most advisors have no idea (or a way to even know) what their clients are paying to the custodial platform the RIA put them on, and whether one custodial platform might have been cheaper for the client than another relative to the services provided.

Which suggests that an alternative approach to compensation for RIA custodians might lead to greater transparency for all parties and better alignment between the interests of custodians, RIAs, and the clients.

The Fiduciary Challenges Of The (Current) RIA Custody Model

One of the key issues with the current RIA custody model is that it is challenging (if not impossible) for an RIA to see what their clients are actually paying for custodial services and, more importantly, there is no way to compare which custodian is more cost-effective (either by being cheaper or providing additional value-added services to the client commensurate with the additional fees they're paying). Because while custodial services are typically seen as being 'free' to the RIA and their clients (as neither party pays an explicit fee for the custodian's services), the custodians must generate revenue in other less transparent ways (including interest earned on client cash, interest paid on securities lending, and fees tied to different investment products) to remain profitable.

The Difficulty Of Comparing Average Costs Between (Publicly And Privately Owned) RIA Custodians

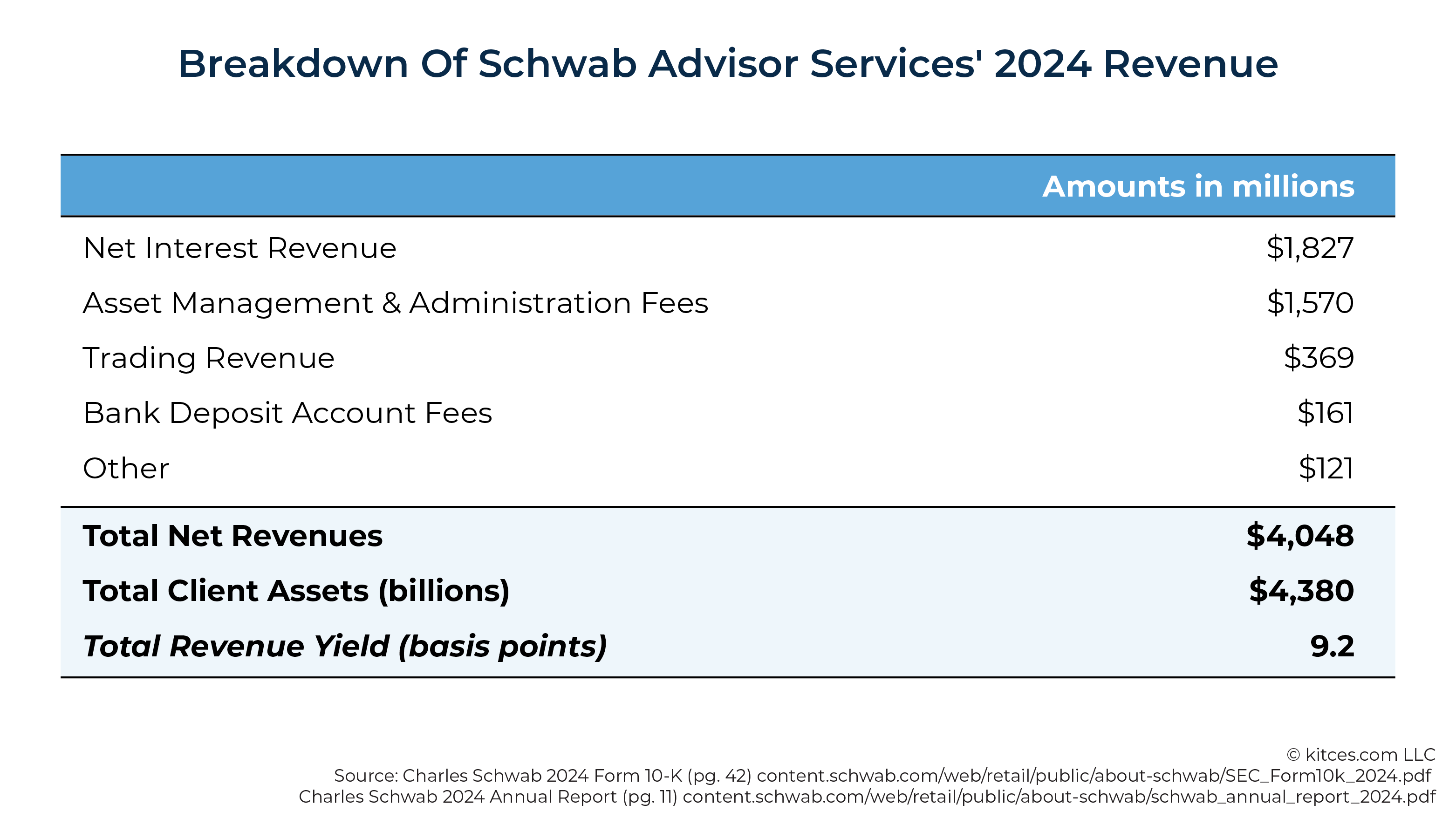

The challenge for RIAs operating as fiduciaries on behalf of their clients is to determine which custodian is most cost-effective, given the costs that clients will incur to have their assets on the custodial platform. In theory, cost comparisons can be relatively straightforward. Yet, in practice, this is a challenge because, while some firms (at least those that are public companies, such as Charles Schwab, the largest RIA custodian in terms of assets on the platform) disclose average data on assets and revenues in their custodial divisions (e.g., in 2024, Schwab earned $4.048 billion in revenue from its advisor services division with year-end client assets in the division of $4.38 trillion, earning approximately $4.048 billion ÷ $4.38 trillion = 9.2 basis points of revenue on advisory client assets), others advisor platforms (including Fidelity, the second-largest RIA custodian) aren't publicly traded and thus aren't required to report publicly, making cost comparisons between platforms nearly impossible.

Notably, RIAs aren't necessarily required to choose the lowest-cost custodial option for their clients. Nonetheless, if an RIA did choose a more expensive custodian (particularly given that the costs of using the custodian come out of the client's pocket), the firm would, at a minimum, need to be able to justify why that option was chosen and how it would benefit the client (e.g., a particular custodian might offer superior technology to execute trades and/or better service to resolve client issues). Though, given the lack of price transparency amongst custodians, such a calculation is nearly impossible to make!

Simply put, in the current environment, the RIA custodians that are more expensive than their peers don't have to justify what additional services they offer for their higher costs, because no advisor even knows what the client cost is to begin with!

How RIAs Currently Manage And Minimize Clients' Custodian-Related Costs

In a world of varied and opaque expenses that their clients pay for custodial services, it's up to RIAs to attempt to minimize these costs (potentially taking up advisor time that could be used for direct client service or other responsibilities). For instance, an advisor might ensure client cash doesn't sit in (typically low-yielding) custodial cash-sweep programs any longer than it needs to (perhaps by taking the time to trade out of it into a higher-yielding money market fund) or take time to negotiate better lending rates for clients seeking margin or securities-backed loans.

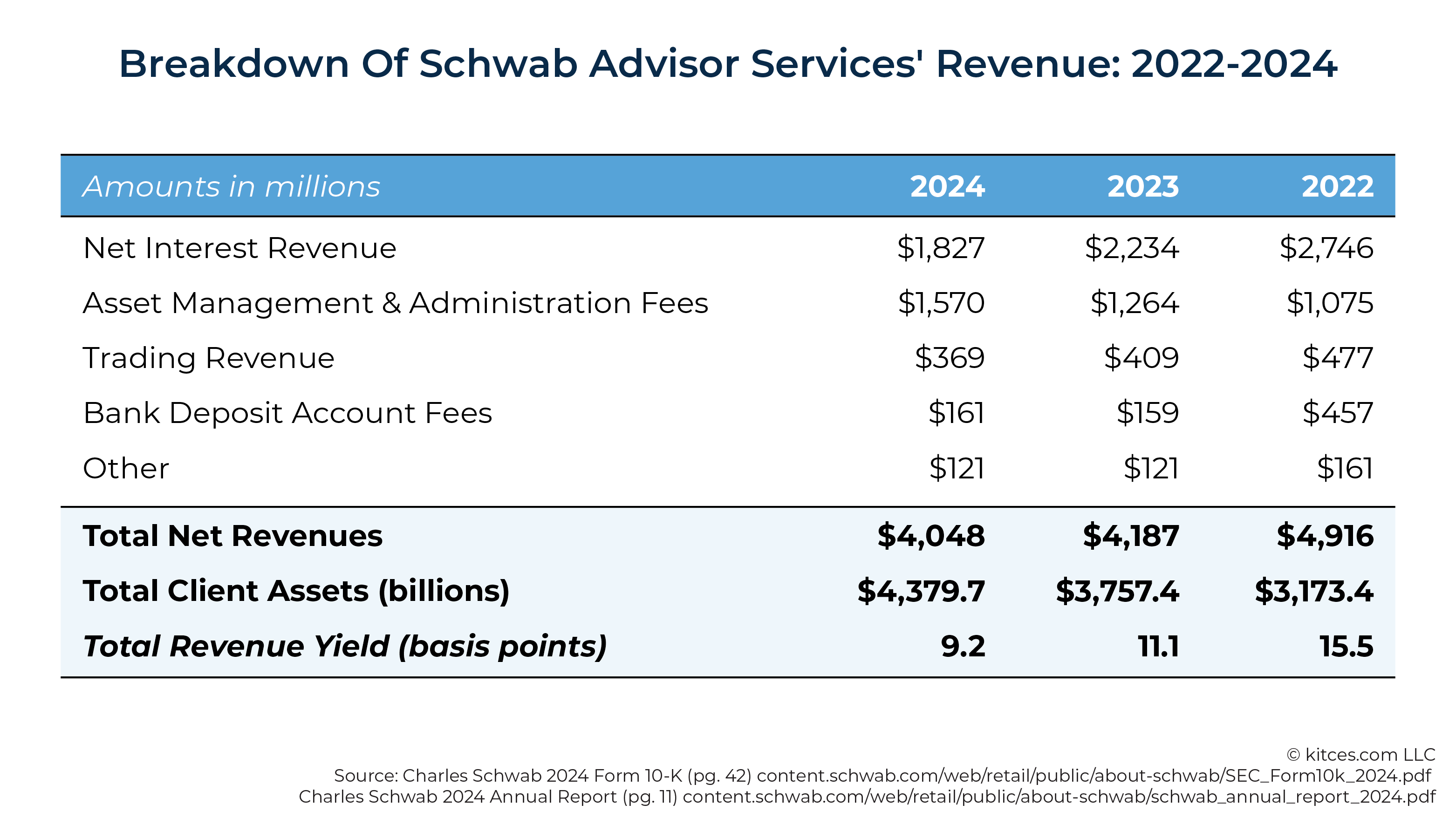

Of course, the more effective advisors are at minimizing custodial-related costs for their clients – either via staffing for more proactive trading, implementing technology to monitor for excess cash, or more aggressively negotiating (e.g., in the case of rates on margin loans) – the less revenue the custodians themselves receive. Which, in practice, has played out in recent years, as public filings from Schwab reveal that its revenue yield from RIAs has steadily eroded over the past five years, as RIAs get better at monitoring and minimizing the custodian's revenue streams. From leveraging portfolio management software in order to monitor for and rapidly trade into higher-yielding cash options, to the rise of third-party cash solutions for RIAs (like Flourish, StoneCastle's FICA, and MaxMyInterest), to the ongoing shift of advisors using lower-cost investment vehicles and ETFs instead of mutual funds that brokerage platforms historically received greater servicing fees for. (Notably, the phenomenon is almost certainly not limited to just Schwab; they simply happen to be the RIA custodian that is publicly traded with a detailed breakout of their Investor Services versus Advisor Services revenue!)

In response to their eroding revenue from this ongoing cat-and-mouse game, RIA custodians have been increasingly incentivized to make it harder for advisors to minimize the custodian's revenue. Thus, for instance, over the past year, Schwab has cut the yield on its cash sweep products (the default destination for investor cash from trading proceeds and other sources) from 0.45% to 0.05% (at a time when its money market funds are yielding greater than 4%), while Fidelity said it will convert the default sweep for RIA's non-retirement client cash balances from money market funds (with the largest Fidelity money market fund currently carrying a 7-day yield above 4%) to its in-house cash management product, FCASH (which offers a 2.19% yield). This adds more pressure for advisors to proactively monitor and trade clients out of cash sweep as quickly as possible. Further, custodians can limit access for clients on their platform to only their proprietary money market funds (or 'partner' money market funds that provide the custodian a behind-the-scenes revenue share at the client's expense), when funds from other providers might offer higher yields… which, in turn, led to a recent hubbub when BlackRock launched a money market ETF (that any RIA and their clients might access from any custodial platform!). Or the custodian 'encourages' advisors to use the platform's own proprietary funds (on which they also earn asset management fees).

In sum, the fiduciary and professional responsibility RIAs have to ensure their clients aren't incurring more costs than necessary for the services they are receiving (e.g., earning less interest on cash-sweep products than they might elsewhere) – lest they face real fiduciary liability for not fulfilling their responsibilities to their clients – is leading them to spend more time on activities like moving client cash to higher-yielding money market funds and incurring their own time costs to avoid RIA custodians undermining the RIA's fiduciary fulfillment. And as advisors are increasingly successful at the game they're forced to play, it is paradoxically undermining the revenue of RIA custodians as well.

All of which might lead some advisors (and perhaps custodians tired of the bad press they receive for playing this cat-and-mouse game with RIAs and their clients) to wonder whether there might be a better alternative model for custodians to get paid for their services?

Flipping The RIA Custody Model 'Upside-Down' For Better Fiduciary Alignment

With the current RIA custody model creating challenges for firms to fulfill their fiduciary responsibilities to their clients – and putting their interests at odds with those of the custodians they work with – both RIA firms and custodians have an interest in finding an alternative. One possible option would be for the RIA custodian to charge a basis-point fee to each client of RIAs on its platform, equal to the average fees they're earning under the current model (so the custodian continues to earn the revenue it needs to provide its services), and then apply a credit to the client's statement for any other revenue the custodian is earning – which, in many cases, might fully offset the custodial fee anyway (but done at the client's discretion of how they wish to pay!).

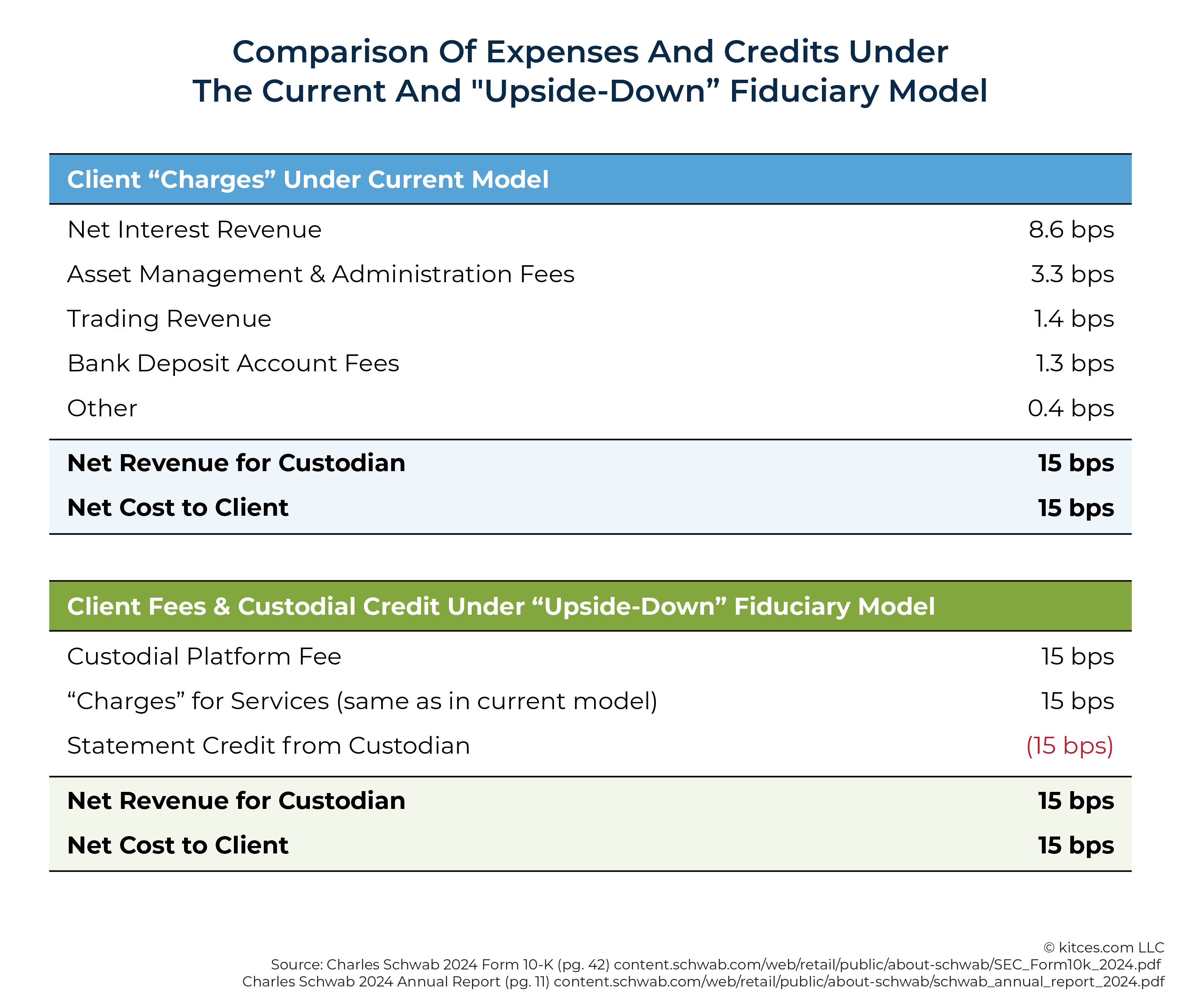

For instance, take a custodian that is currently earning an average of 15 basis points (bps) of revenue on RIA client assets. With this new structure, the RIA custodian would charge clients a 15 bp fee, while it may also still bring in 15 bps from their underlying custodial revenue streams (e.g., 8.6 bps from net interest revenue, 3.3 bps from asset management and administration, 1.4 bps from trading revenue, 1.3 bps from bank deposit account fees, and 0.4 bps from other sources) for an average of 30 bps of revenue. However, because that would be 'double-dipping' by the custodian – and, more practically, no advisory firm or its clients will want to pay an RIA custodian a basis point fee for the platform and still have the platform make money off them on the underlying holdings and their associated custodial revenue streams – the custodian would then apply a statement credit for the revenue generated from each client through the aforementioned custodial services (in this case, 15 bps).

In this way, the custodian would continue to earn a net fee of 15 bps of revenue per client (15 bps custodial fee + 15 bps underlying custodial revenue – 15 bps statement credit to client = 15 bps net revenue) and the client (similar to the current model, where costs are 'hidden') would have no direct net out-of-pocket cost (as the 15 bp custodial fee would be offset by the 15 bp statement credit). The key, though, is that the amount a client would pay for custodial services becomes crystal clear (15 bps), with any revenue generated from their activity on the platform being remitted to them through the statement credit.

How Outcomes Could Vary From Client-To-Client Using A Fiduciary Fee Model For RIA Custody

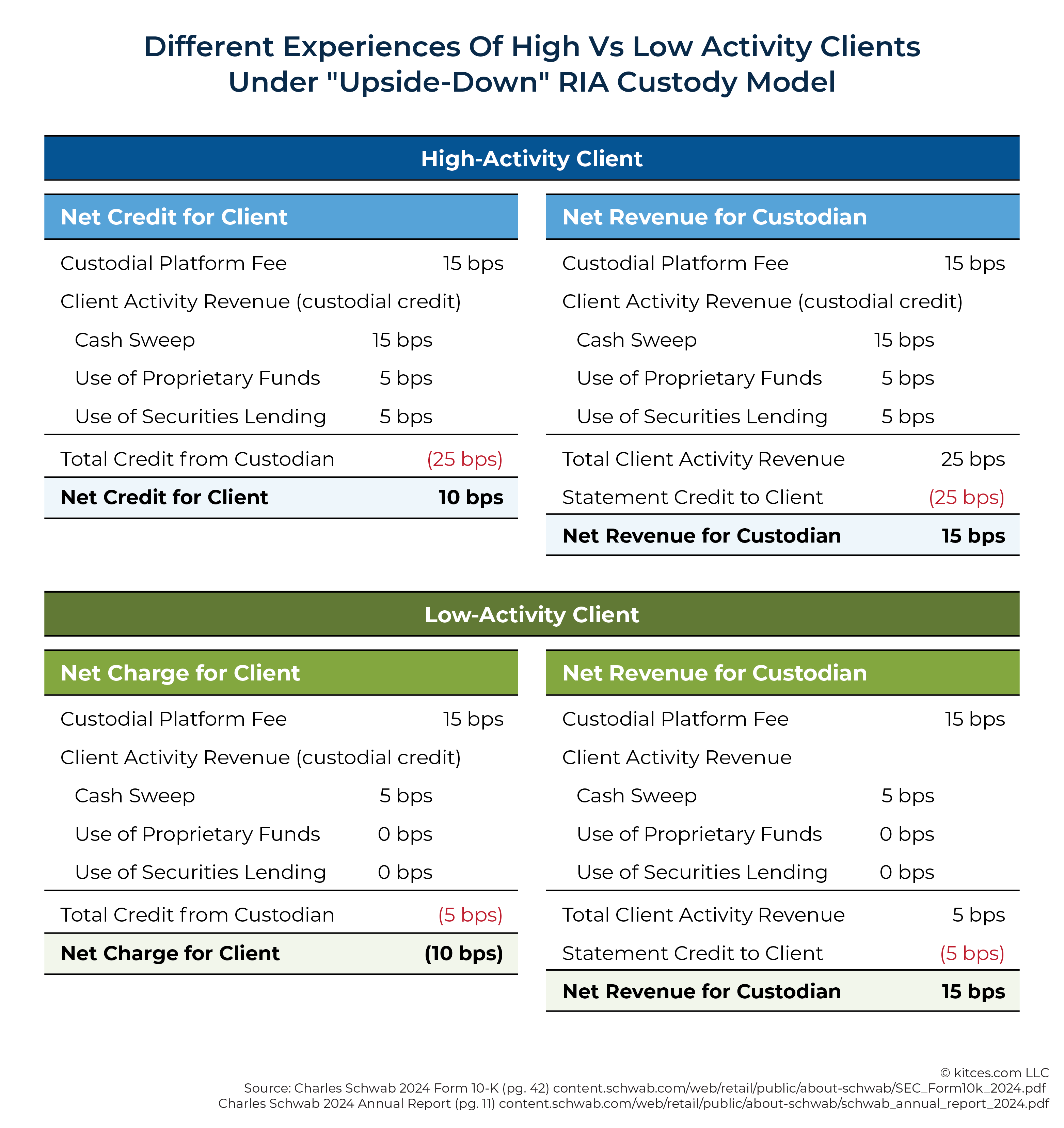

Under the 'upside-down' custodial fee model, the custodian can set the per-client fee at a level that reflects their existing average revenue from their underlying custodial services; the purpose is not to undermine the revenue that custodians earn for their services, but rather to preserve that revenue in a more transparent manner (and in such a way that clients can more effectively control the cost based on their utilization of the custodian's services). However, because individual clients will use the custodian's services in different ways – and generate different levels of revenue for the custodian – they will experience varying outcomes under this more fiduciary model based on the custodial revenue they generate (and thus the size of the statement credits they do or don't receive).

For instance, assume a client holds a significant amount of cash in the custodian's cash-sweep product, is active in securities-based lending, and uses margin loans, generating 25 bps of revenue for the custodian. Under the existing system, the custodian simply keeps all of this revenue and turns a better profit on the client (who might not realize the extent of the costs they are incurring, particularly when it comes to cash-sweep balances – and that they are paying an above-average rate, effectively subsidizing other clients who keep less cash with the custodian and therefore pay less for the same services!).

However, under the alternative more fiduciary system, the client actually gets positive returns by using the RIA custodian (paying the 15 bp fee but receiving a 25 bp credit for the revenue generated through their activity on the platform, for a net credit of 10 bps… that is added to their investment returns), while the custodian continues to make its requisite 15 bps of revenue.

Alternatively, a client who is effective at minimizing custodial revenue (e.g., uses only low-cost ETFs, incurs no trading fees, keeps cash-sweep balances to a minimum) might only generate 5 bps for the custodian (possibly less revenue than it costs to serve them), a common circumstance in the current model (particularly if the client has an advisor who recommends low-cost products and is mindful about cash-sweep balances!). Under the current model, these clients are either subsidized by more active clients, or else incur indirect costs – for example, when their advisors have to reach particular asset minimums or are outright assessed platform fees as a consequence for 'doing the right thing' by putting them into lower-custodial-revenue allocations. However, under the proposed system, clients who don't generate enough revenue to cover their costs pay the balance themselves (through the standardized per-client fee) instead of being subsidized by advisor platform fees, minimums, or other higher-revenue clients who effectively pay on their behalf.

New Incentive Structures For Advisors And Their Clients… And RIA Custodians

Once clients pay a platform fee and after any indirect custodial revenue is credited back to them under this more fiduciary model, incentives for both advisors and custodians change significantly. Advisors may be more inclined to support clients' use custodial services (e.g., securities-based lending, lines of credit, or leaving more client cash in cash-sweep programs), because the resulting statement credits can offset – or even exceed – the new explicit basis-point fee, allowing clients to actually profit by engaging with the custodian's services.

From the custodian's perspective, this more fiduciary model incentivizes several advisor- and client-friendly changes that support the custodian's own business. For instance, because of the statement credit, there would no longer be a benefit to making it harder for clients to generate higher yields on their cash (because any profit from cash sweeps would be credited back to the client anyway). This incentivizes custodians to offer higher yields to attract more assets to their platform (especially if their custodial fee is lower than the competition) – not by offering low-yield cash funds and crediting back to the client, but by offering high-yield cash funds and attracting advisors and their clients' cash into those high-yield options where the custodian earns their 15bps platform fee. Which means advisors and their clients would be more likely to engage, because the cash yields themselves are better than available alternatives.

In addition, custodians negotiating revenue-sharing and other distribution agreements with asset managers would take on a different context when the revenue is no longer supplemental to the custodian, but instead provides more appealing statement credits to clients (making it more appealing for clients to move assets to the platform and expanding the assets on which the custodian is earning the custodial fee). For instance, a custodian could seek to be the most open platform with no revenue-sharing (improving its relationship with asset managers) because the client is going to pay their custodial fee anyway – and with no revenue-sharing costs, the asset manager could lower the fees on their funds. In fact, in the case of mutual funds, custodial platforms could even negotiate for alternative lower cost share classes (as even some Advisory/Institutional shares still have some layer of costs associated with revenue with the custodian, but with a custody fee model with statement credits, these costs would be redundant and could be removed). The end result would benefit clients who purchase those lowest-cost share classes, along with supporting the asset manager that offers 'superior' lower-cost versions of funds that are otherwise higher-cost on other non-custodial-fee platforms.

In other words, in this world the incentive for the custodian isn't to get the best revenue-sharing agreements, but rather to gain access to (or even support the development of) investment products with the lowest expenses – making the platform more attractive to advisors and their clients and gathering more assets on which the custodian charges the custodial fee. Custodians with their own proprietary funds could develop below-market-cost funds as a strategy to bring advisors and their clients to the platform (offering superior products to "earn" their custody fee). Which is itself aligned to advisors who predominantly charge an AUM fee and also want to bring more assets onto the platform (ideally one aligned to their business model, rather than one where they need to protect their clients from the custodian's revenue model!).

In sum, under this alternative more fiduciary model for RIA custody, clients would always pay their actual costs to the custodial platform (so some clients aren't 'overcharged' to cover the costs of others), advisors would have an incentive to utilize the platform to generate more statement credits for their clients or to consolidate assets to gain access to superior investment alternatives, and custodians would have more incentive to drive costs down and negotiate not for better revenue-sharing agreements but to get access to (or develop for themselves) superior lower-cost versions of investment funds that are possible when there are no longer revenue-sharing agreements. Or at least to create more statement credit opportunities to make their net pricing look lower in cost – or even net positive – to clients, for whatever revenue the custodial platform can still generate and credit forward.

Which, together, would ultimately make it easier for advisors to fulfill their professional responsibilities as a fiduciary!

Practical And Implementation Issues With A Fiduciary Fee For RIA Custody

While the concept of an 'upside-down' RIA custody model – charging clients a platform fee and crediting back the revenue the custodian generates from their activity – is relatively straightforward, actually implementing such an approach could be challenging.

To start, a key point is to recognize that 'just' charging a custody fee alone doesn't work if clients don't get something unique and valuable to compensate for the fee they're paying. As a result, charging a custody fee on top of existing custodial revenue sources – which effectively becomes a form of double-dipping – isn't likely to be appealing (and in practice, those platforms that have tried have struggled with adoption).

Similarly, a fee-or-commission choice – for example, where custodians offer advisors the ability to select which arrangement they'd prefer – is also likely destined for failure, because it simply amplifies the existing unhealthy dynamic: Advisors who are already navigating custodial platforms to minimize costs for the benefit of their clients will eschew a custodial fee that would constitute a fee increase for them, and advisors who choose the custodial fee will exclusively be those for which the fee is a lower cost for their clients. Which is effectively an unsustainable lose-lose scenario for the custodian (as lower-revenue clients will avoid the fee, and higher-fee clients will choose the fee to reduce the custodian's revenue). Because the core dynamic hasn't changed: Advisors are helping their clients navigate custodial platforms to save costs for clients and reduce the custodian's revenue, and it takes a full reconstruction of the model – where the custodian, advisor, and client are all aligned (which means charging a full-value custodial fee for everyone, and crediting each client back their fair share) – to get custodians back to the point where advisors will support their platforms instead of actively undermine them to look better in front of their own clients!

In turn, then, the key issue becomes the custodian's ability to implement the client statement credits that lie at the heart of making an 'upside-down' fiduciary fee system attractive to all parties. However, doing so would come with non-trivial complexities and questions not only in terms of systems but also in determining fairness to RIAs and their clients. For example, a custodian would have to determine whether the statement credit would be allocated across all clients on their platform at the client, account, or individual holding level. Though, arguably, any of these is more fair than some clients paying 5 bps and others paying 25 bps today, but determining exactly what's allocated and how it's done brings up real challenges.

Custody Fees With Statement Credits To Clients Could Shed An (Uncomfortably) Bright Light On How Costs Differ Amongst Custodial Platforms

An RIA custodial model that combined a fiduciary platform fee with statement credits to clients (for any underlying custodial revenue generated via their accounts) would bring into the open the true and total costs that clients pay for different custodial services. Which would inevitably vary amongst custodians, as they provide different services to RIAs and their clients, and have different internal costs and economies of scale. This could lead to some uncomfortable conversations and decisions for advisory firms that suddenly have to explain why one client went to RIA custodian A to be charged 15bps, while another went to RIA custodian B to be charged 20bps.

In addition, while advisors certainly can choose to direct clients to more expensive custodial platforms in exchange for better levels of service (e.g., better execution on trades), the truth is that not all custodial offerings that may impact the advisor's choice of RIA custodial really benefit the client. For example, many custodial platforms offer practice management services for 'free', but if those services drive up the direct cost of custody to the client, some clients might be less keen to pay a higher basis-point fee just so their advisor can be on the platform to glean practice management benefits that help the advisor scale with other new clients – especially if those resources don't enhance the client's own level of service.

Relatedly, because custodial referral networks are often restricted to firms with certain asset totals (effectively inducing the advisory firm to put more client assets with that particular custodian to be eligible), placing clients on a higher-fee platform to allow the firm access to new custodial referrals could create awkward conversations at best (or outright constitute a fiduciary breach). In theory, the conflict of interest exists already, but when RIA custodial services feel commoditized and interchangeable – and there is no fee transparency – there's no way to tell whether clients who are directed to custodian B instead of custodian A are actually paying a higher fee… until the custodial fee becomes transparent.

In addition, because custodians tend to benefit from scale as they grow, greater transparency on custodial pricing could introduce the risk that the largest players just get larger, as their economies of scale allow them to charge lower fees. Smaller custodians, by contrast, may find it hard to compete on price – and may struggle to validate higher costs when they have less revenue and fewer resources to scale. In the long run, this could inhibit RIA custodial innovation. Or, at the very least, it could raise the cost of what it takes to launch a new competitor – one that would need to offer scale-competitive prices even if not yet operating at scale.

Further, the reality in the modern custodial landscape is that there are no breakpoints for advisory firms as they grow in size and scale. Whether a firm has $10 million or $10 billion with the platform, the custodian earns the same revenue percentage from sources like cash sweep, 12b-1 fees, and other streams. As a result, this has led to the challenging reality that most custodial platforms set asset minimums for firms to join. These minimums help 'ensure' there are enough assets on the platform against which they can generate revenue, as there's a very real overhead cost for the custodian to set up and serve each advisory firm. Which subsequently means that RIA custodians generate far more in profitability from larger RIAs than smaller ones… in turn, RIA custodians often urge smaller advisory firms on their platforms to consolidate – either by merging or outright selling themselves to a larger firm – in order to reduce the custodian's own cost of service.

Yet with a more transparent fiduciary fee for custody, this dichotomy would also be cast into sharper relief, as larger independent RIAs would likely negotiate their own breakpoints on custodial fees (e.g., 13bps above $1B of AUM if the standard fee was 15bps). That would create a world where smaller firms pay more than large firms, and small firms feel pressured to merge – or at least affiliate with – other RIAs to obtain custody breakpoints (though, again, that is arguably just a reflection of the cost realities of RIA custody).

The Challenge Of Charging A Fee When Custodial Services Have Long Been Viewed As 'Free'

While increased custodial fee transparency could shed an uncomfortable light on certain custodial incentives and pricing inequities between large and small firms (and high- and lower-revenue clients), arguably the biggest challenge of instituting a basis-point fee and statement credit system is behavioral. Simply put, clients (and their advisors) aren't used to paying an outright fee for custody. And when something has been provided for 'free' for so long, any fee – no matter how reasonable – can induce sticker shock!

Nevertheless, this is why a statement credit system becomes the crucial catalyst to make the transition. If the platform fee equals the revenue the custodian was already generating – and that revenue came from the client – the net cost would end up being the same for the client (as opposed to previous systems, where the platform fee was stacked on top). The client's statement would have a 15bps custody fee, paired with a 15bps credit, still achieving the same 'net-free custody' status they enjoy today. The difference is that now it's simply transparent.

This model also maintains stable custodial revenue while ensuring that every client pays their 'fair share'. Large clients no longer subsidize small clients, larger firms don't subsidize smaller firms, and everyone pays the same or at least a cost-proportionate basis-point fee. And RIA custodians wouldn't have to have awkward conversations with advisors about paying a platform fee or buying more of the custodian's proprietary funds to boost the revenue they're bringing to the custodian.

Nerd Note:

In 2020, Fidelity began to expand its use of custody fees (either a per-account fee or a firm-level custody fee) beyond the smallest RIAs, resulting in significant consternation amongst affected firms (as well as a pledge from rival Schwab to never charge platform fees). At the same time, Fidelity offered these firms the option to avoid the fee by agreeing to have cash in client accounts swept into proprietary Fidelity money market funds (on which it collected a 42-basis-point fee at the time) or its FDIC-insured cash product.

While this move ostensibly gave firms the choice in how Fidelity would be compensated for the custodial services it provided – and, ironically, was a version of simply charging custody fees to avoid any conflicts of interest about proprietary funds – telling firms they must pay a platform fee 'or else' buy Fidelity's proprietary funds appeared to leave a bad taste in many industry participants' mouths (that Fidelity might have preferred to avoid).

Notably, under the alternative model, clients who are hesitant to pay a basis-point custodial fee could be offered the option by their advisor to use custodian-proprietary funds to (perhaps more than) offset the custodial fee – since the client would receive a statement credit for the revenue generated from their use of the custodian's fund.

The following example illustrates how this could work in practice:

Example 1: Wilma's longtime client Barney expresses concern to her about the custodial fee he has to pay under the new system – even after Wilma explains that he was already compensating the custodian through revenue sources like cash-sweep balances. She tells him that one way to help offset the new fee is by using a proprietary fund offered by the custodian.

While this fund has a 30-basis-point expense ratio – compared with a 15-basis-point expense ratio for a similar fund from another asset manager – Barney will receive a statement credit for the 15 basis points in additional revenue the custodian earns. That credit would offset the 15-basis-point platform fee he's charged.

The net cost to Barney of using the custodian's proprietary fund is the same as using the lower-cost alternative (due to the custodial fee and statement credit). The advisor's fee remains the same, and there's no conflict of interest in the recommendation – it simply becomes an opportunity to provide guidance to the client by helping them understand the different ways they can pay for the custodian's third-party services.

From the advisor's perspective, the 'upside-down' model offers a clearer path to fulfilling their professional responsibilities. By minimizing costs and maximizing statement credits, advisors can better serve their clients while also meeting their fiduciary obligations – namely, by finding the most cost-effective custodial platform. At the same time, this approach doesn't come at a cost to the advisor-custodian relationship, as the custodian's revenue remains stable and secure even as advisors seek to maximize value to their clients.

In the long run, advisor and custodian interests become more aligned, as both aim to attract more client assets – to the advisor's management and the custodian's platform. The custodian can further support that alignment by 'stocking the shelves' with increasingly appealing (e.g., lower-cost investment or higher-yield cash sweep) options, making the custodial platform fee feel worthwhile – much like paying a Costco membership fee to access the favorably priced goods inside the store.

Though at a more fundamental level, the dominant trend in the advisory industry for the past 20 years has been the rise of the RIA model – which, in turn, has spurred such growth of RIA custodians themselves. And consumers have clearly shown that when a more transparent fee model really does result in better alignment of interests – and in turn, better service and outcomes – they will 'vote with their feet' and choose a provider charging a fee (e.g., an RIA) over one earning commissions (e.g., a traditional broker or agent). Which means if consumers have already expressed a preference for the RIA's transparent fee model, there's no reason why RIA custodians couldn't participate in the trend and enjoy the greater growth benefits that RIAs themselves have already gained from the approach!

Ultimately, the key point is that the current RIA custody model presents fiduciary challenges for advisors, who have no feasible way to compare the costs for their clients of different custodians they might work with. At best, advisors can take steps to minimize how much their clients 'pay' the custodian (e.g., through minimizing balances in cash-sweep programs) – but doing so costs advisors valuable time and steadily undermines the traditional RIA custodial business model anyway, as custodians' revenue yields continue to dip as advisors get better and better at 'playing the game'.

Which suggests that an alternative approach – pairing a clear basis-point fee for the client with statement credits for revenue generated by their use of custodial services – not only offers greater transparency in the costs for custodial services, but also better aligns the interests of clients, advisors, and the custodians they work with. And, in the end, that alignment would allow advisors to more effectively fulfill their fiduciary obligations to clients!

Leave a Reply