Executive Summary

In the early days of the Registered Investment Adviser (RIA), financial advisors who didn’t affiliate with a broker-dealer had no way to actually manage investment accounts on behalf of their clients… short of having clients open “retail” investment accounts with direct-to-consumer “retail” brokerage platforms, and grant their advisor a limited power of attorney to call in (pre-internet!) and place trades on their behalf, which was a win for the client (who had their portfolio managed), the advisor (who had a platform to manage their client portfolios), and the brokerage firm itself (that generated trading commissions every time an advisor traded on behalf of their clients). In the decades since, the nature of RIA platforms has evolved tremendously, from advisors phoning in trades to an entire ecosystem of RIA custodians providing trading, billing, and supporting technology for RIAs to use… but still all predicated on a model where the brokerage-firm-as-RIA-custodian profits from advisors at the expense of their clients.

In this guest post, Yang Xu – CEO of TradingFront which competes for RIA custody services in partnership with Interactive Brokers – explores how the RIA custodian business model continues to evolve, why the recent onset of zero-commission trading has merely shifted how (but usually not whether) clients are paying for trading, and how advisors can do their due diligence to understand the real investment costs that clients may face (and revenue sources that RIA custodians still generate) through the platforms that RIAs purportedly use for “free” (as in the end, “free” rarely ever is).

“Pay-to-play shelf-space agreements” are one way that RIA custodians offer No-Transaction-Fee (NTF) funds, which effectively embed trading costs within the mutual funds themselves (with little way for advisors or their clients to identify what the exact breakdown of what those 12b-1 and sub-TA costs may be). And with the shift to ETFs, that have their own unique rules regarding revenue-sharing to RIA custodians, new “data agreement” flat fees (potentially up to $650,000 per agreement from each asset manager to each advisor platform!) are now emerging as a way for RIA custodians to generate revenue in exchange for providing data that shows asset managers how their products are really being used.

Another major indirect cost of RIA custodial platforms is found in interest earned (or rather, not earned) on client cash holdings. Because when cash is maintained in a client account, it is often by default “swept” into a proprietary mutual fund of the RIA custodian, or even a bank deposit account of a subsidiary bank owned by the RIA custodian, yielding net interest income – the difference between what the cash position actually earns, and the lesser amount that is paid to the client – that is collected by the RIA custodian. Which for some RIA custodians is so large, that net interest from client cash actually forms the majority of the entire RIA custodian’s revenue and profits!

In recent years, another growing source of revenue for RIA custodians to generate from advisors and their clients is Payments For Order Flow (PFOFs), which custodians receive for selling the placement of client trade orders to high-frequency trading firms. And while directed trading to high-frequency trading firms can potentially improve trading efficiency (even with the drag of PFOFs), RIAs generally have very limited means to assess the actual quality of execution (which is actually becoming more difficult because rising PFOF and a rising volume of trades occurring off the traditional exchanges actually makes it systemically harder to benchmark good trade execution in the first place!).

Of course, the reality is that RIA custodians are businesses that can and should be able to generate revenue and profit from the services they provide. Still, though, the current model of RIA custodians generating such ‘indirect’ revenue from the clients of advisors, coupled with a dearth of any requirements to disclose financial statements and pricing (at least for non-publically-traded RIA custodians) make it difficult to research what RIA custodians are truly charging and whether it is a fair and competitive price to the available alternatives. Which, ironically, raises the question of whether advisors may soon even seek out RIA custodians that require RIAs to openly pay (fully disclosed) trading commissions and platform fees, if only to ensure full disclosure and a clear understanding of all expenses for the advisory firm and its clients (and an opportunity to price-shop for other RIA custodians that may offer advisors and their clients a better deal)?

The bottom line, though, is simply to understand that ‘free’ services rarely (if ever) exist when those services entail work, which certainly includes the business of brokerage and RIA custodial firms. And for financial advisors who aim to provide full disclosure of all expenses in the interests of their clients, and want to make good decisions on behalf of their clients regarding which platforms to affiliate with, it’s crucial to peel the layers of the onion and gain an understanding of the underlying costs that clients are incurring with their platform of choice… a due diligence process that applies to not only selecting investments for client portfolios but also where those portfolios are custodied and traded, too.

Now that commission-free trading has officially become the status quo in the world of investing, it brings up some potentially troubling implications for custodians, RIAs, and their clients: Is ‘free’ truly free?

We believe the answer is ‘no’ when considering some of the hidden ways these retail brokers make up for zero commissions through fiduciarily-questionable revenue-generating practices. Particularly when it comes to these brokers’ massive RIA custody businesses, these non-transparent retail pricing schemes bring up troubling issues for RIAs and their clients.

These non-transparent (and non-fiduciary) practices include 1) revenue-sharing arrangements with mutual funds, 2) the harvesting of client cash assets through bank sweep programs, and 3) the increasing prevalence of “payment for order flow”, whereby brokerages sell their client’s orders to institutional traders. We believe that RIA clients are still paying for putatively ‘free’ trading while RIAs themselves are benefitting from these indirect subsidies through ‘free’ custody services.

Accordingly, we believe it is in the best interests of the industry to shed light on these trends and industry practices and provide the counter-case that pricing for RIA custodial services should be more direct and transparent so that advisors and their clients know exactly what services they are receiving and paying for consistent with a fiduciary model – one that has been so successfully embraced by the industry’s leaders, independent RIAs themselves.

If these opaque pricing models continue to flourish, there could be ramifications in the form of potential new government regulation, litigation, and the continued erosion of the reputation of the financial services industry in the eyes of the public (as they eventually discover what they’re really paying and what it actually costs them), which could drag down the RIA industry when RIAs ‘choose’ to put their clients into such opaque pricing arrangements with their custodians.

To prevent this from happening, we are hopeful we can initiate change by educating and arming advisors with the truth and facts about how RIA custodians are offering ‘free’ pricing that clearly isn’t (and can’t be), and by creating an industry movement to demand more transparency in the custodian/RIA/client relationship.

How Much Do RIA Custodians Really Cost Financial Advisors And Their Clients?

There’s no doubt that everyone loves free stuff, but is anything ever truly ‘free’? Of course not. Every brokerage firm offering ‘free trading’ and ‘free custody services’ still has to pay for operating, marketing, technology, and regulatory expenses, while generating profits for shareholders. And while commissions used to be the bread and butter of brokerage firms, over the years, the RIA custodian’s focus has shifted to other sources of revenue… culminating to the point that last year, most walked away from trading commissions altogether because other revenue sources were so much more lucrative.

The Rise Of Pay-To-Play Shelf-Space And Revenue-Sharing Agreements For No-Transaction-Fee (NTF) Platforms

One way brokerages can effectively charge a fee, yet still claim to be ‘free’, is via pay-to-play platform arrangements in which mutual funds and other asset managers pay to have their solutions made available on the RIA custodian’s platform in the first place.

Accordingly, the standard industry practice for decades amongst broker-dealers (including the broker-dealers that serve as RIA custodians) has been that sponsors of these products need to compensate the brokers, via a revenue share, for ‘preferred’ placement on their platforms (e.g., to be highlighted in their No-Transaction-Fee platform), an arrangement commonly known as a “shelf space” agreement.

Of course, asset managers cannot just magically produce additional revenue to pay such platform costs, which means those costs ultimately are passed on to (i.e., embedded within) mutual funds and other asset management vehicles. Yet this arrangement effectively hides the RIA custodian’s revenues (and the associated investor cost) from the end-user investors and their advisors themselves, since there is no standalone line item on any statement they can point to that discloses how much of a fund’s or asset manager’s underlying expense ratio is for operation and management of the mutual fund itself, and how much is actually just a platform fee to the RIA custodian or other brokerage firm.

How much are those costs? When it comes to mutual funds, the expenses often include the mutual fund’s 12b-1 fee (up to 25 basis points) and may include additional sub-transfer agent (sub-TA) fees that often amount to as much as another 10 basis points. In the case of ETFs – where 12b-1 and sub-TA fees are not built in – some firms simply charge so-called “data agreement” flat fees (that they charge to the asset managers to give them back the data about how their ETFs are actually being used). The ceiling of this fee is often very high and hard to find. Is this the tip of the iceberg from at least some publicly available information from wirehouses? Wells Fargo charges $650,000 maximum, Morgan Stanley charges $550,000 maximum, and UBS charges $300,000 maximum.

We can further examine Charles Schwab for insights into how this works. ERISA Section 408(b)(2) requires brokers to disclose fees paid to them by service providers (at least with respect to Schwab’s retirement plan business), and the requisite fee disclosures include payments for shelf space agreements. In Schwab’s 2019 408(b)(2) disclosure report, the company sets forth compensation rates received by Schwab from fund companies. For No-Transaction-Fee funds (including OneSource funds), the rates were, “0.30% to 1.10% of fund assets”. That’s a pretty wide range, so we need to dig deeper to understand what actually happens in practice.

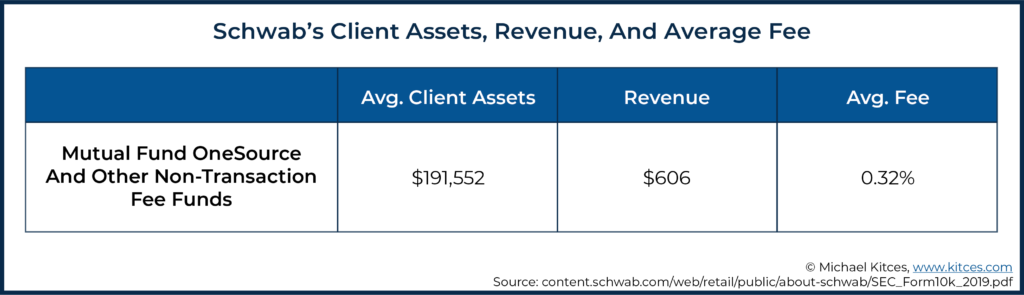

Turning to Schwab’s 2019 10-K, we can see how much revenue this practice generates. For 2019, the following table sets forth client assets and revenues (dollar amounts in millions) and the associated fee yields:

So it appears that the average third-party (non-Schwab-affiliated) fund is paying Schwab 0.32% for the privilege of being offered on the “No-Transaction-Fee” (NTF) platform, which equates to $606 million in revenues for Schwab. This seems broadly consistent with the 408(b)(2) disclosure.

From the mutual fund’s perspective, this makes sense. They get added visibility and distribution of their products, especially given how consumers have shown a clear preference for not paying upfront trading commissions and ticket charges (in light of the popularity of such NTF platforms). And the whole purpose of a 12b-1 fee – which is the bulk of these payments – is to help mutual funds cover their marketing and distribution costs.

But when these products are listed as “commission-free” or “no-load”, are they really “free” with “no transaction fees”? No, the transaction fee and other costs are just being covered by the mutual fund or asset manager upfront, buried in the expense ratio of the sponsor. In other words, mutual funds and even some ETFs simply pass these transaction costs along to investors by marking up their expense ratio to generate the additional revenue needed to pay the broker-dealer and RIA custodians for shelf space to cover those trading commissions… while investors (and their advisors) struggle with little way to scrutinize the practice.

In fact, one of the primary reasons that certain fund families like Vanguard have lower expense ratios is specifically because they have a history of not paying shelf-space and other revenue-sharing fees to broker-dealers and RIA custodians. Similarly, DFA funds have for many years faced higher trading commissions on RIA custodian platforms than their other mutual fund brethren, specifically because they did not pay back-end revenue-sharing to platforms, as so many other fund families have (thus ‘forcing’ the RIA custodian to make up the revenue with higher upfront ticket charges instead).

More generally, though, the point is simply that “free” trading subsidized by asset manager pay-to-play arrangements has largely converted “zero commission” trading into “commission-based trades covered by the internal expense ratio” of the funds being bought and sold. Ultimately, those trading costs are still being passed along to clients – they are implicitly paying this higher ongoing price as compensation for the “free” custodial services that advisors receive for their RIA.

Net Interest Income And Other Ways RIA Custodians Earn Yield On Client Cash

Platform pay-to-play arrangements aren’t the only place where “free” can sometimes really mean “fee.” Do you use margin or other securities-based lending programs? Or, more commonly, maintain cash positions in your clients’ accounts (whether as an ‘investment allocation’, to generate their retirement spending distributions, or simply to handle the advisory firm’s own fee payments)? These are other avenues of income that brokerage firms currently tap to defray commission and RIA custodial costs.

As an RIA, how much flexibility is there to competitively shop margin loan rates at your current broker, as compared to the competition? What about interest on cash balances? If you keep clients’ uninvested cash in a portfolio, it typically gets swept into an account with the brokerage’s banking arm, where the broker commands a higher rate of interest, generating what is called “net interest income”.

In fact, one of the primary ways that RIA custodians fund their disruptive retail practices is by harvesting client cash, paying investors just a small portion of the interest earned, and keeping the rest to make up for their give-back in commission revenues from “free” trading and “free” brokerage and “free” custodial services.

Today, in some cases, clients are earning tiny amounts as low as 0.01% on those cash balances, which can then be re-deployed or lent out by the RIA custodian at higher rates to earn a spread, adding up to billions across the industry, year after year. Let’s take a very simple example to illustrate how net interest works for the RIA custodians.

Example 1: Jeremy is a brokerage client at ABC brokerage and custody services, where he maintains a cash balance of $10,000. Let’s also say the yield on 1-year Treasury bills is 0.10%, so ABC agrees to offer Jeremy an interest rate of 0.06% on your cash.

Thus, if Jeremy leaves his cash in the account for a year, ABC can invest it in t-bills, which will generate $10,000 * 0.010% = $100. Out of this $100 of interest from the t-bills, ABC pays Jeremy the negotiated interest of $10,000 * 0.06% = $60. The remining $40 is profit, or “net interest income” to ABC as the broker. In this case, acting as the broker, ABC has split the interest earned on Jeremy’s cash 60/40 with Jeremy.

Nerd Note:

On an RIA custodian’s Profit-And-Loss Statement, “Interest income” can technically include some other items, such as revenues from margin loans, securities lending, and other miscellaneous sources, in addition to this hold-cash-and-earn-interest-spread mechanism. Thus, while this example is an oversimplification, it does nonetheless highlight the primary driver of the Interest Income revenue category.

The Cash Cow Of Sweeping Client Cash To An Affiliated Bank

Now let’s move to the bigger picture to understand how this simple cash management idea has been occurring in recent practice in a large brokerage firm, TD Ameritrade (“TDA”).

The discussion below is based on figures from a PDF entitled “Transforming lives and investing for the better”, which covered TDA’s fiscal 2020 2nd quarter results.

Since this is right around the time Schwab announced it was acquiring TDA, we can get a close look at internal cash management details at the firm, as there was a lot of disclosure associated with the proposed acquisition. The details provide a lot of insight into the current situation at the big brokerages.

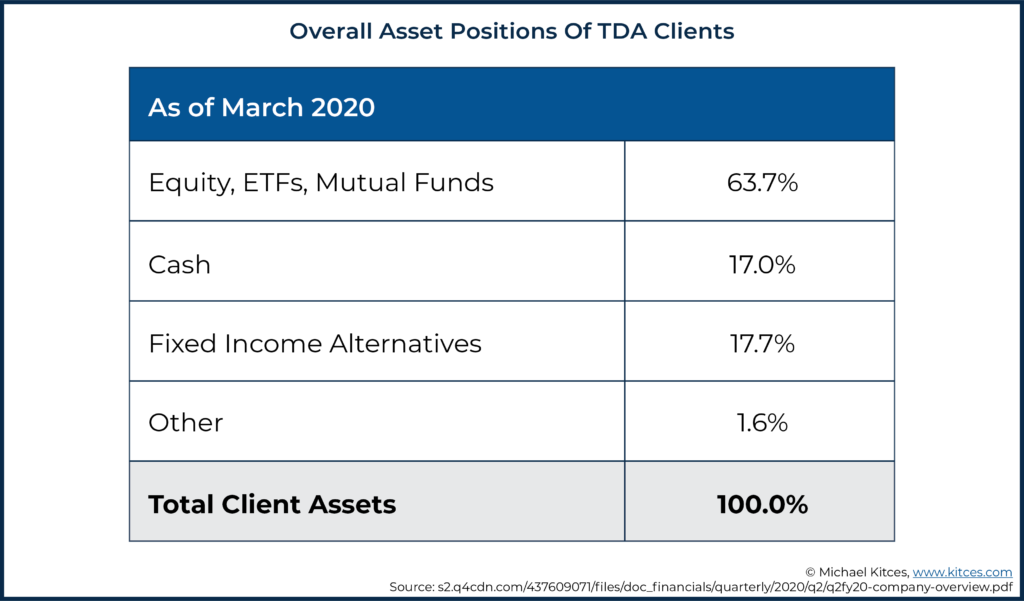

First, let’s take a look at the overall asset positions of TDA clients. It was as follows [Page 9 of “Transforming lives and investing for the better” PDF]:

As you can see, as of the most recent quarter, clients (including both RIA and retail) held an average cash position of approximately 17% in their accounts. This represents cash available to TDA to earn net interest income. How much net interest income did TDA earn, and how did it earn it?

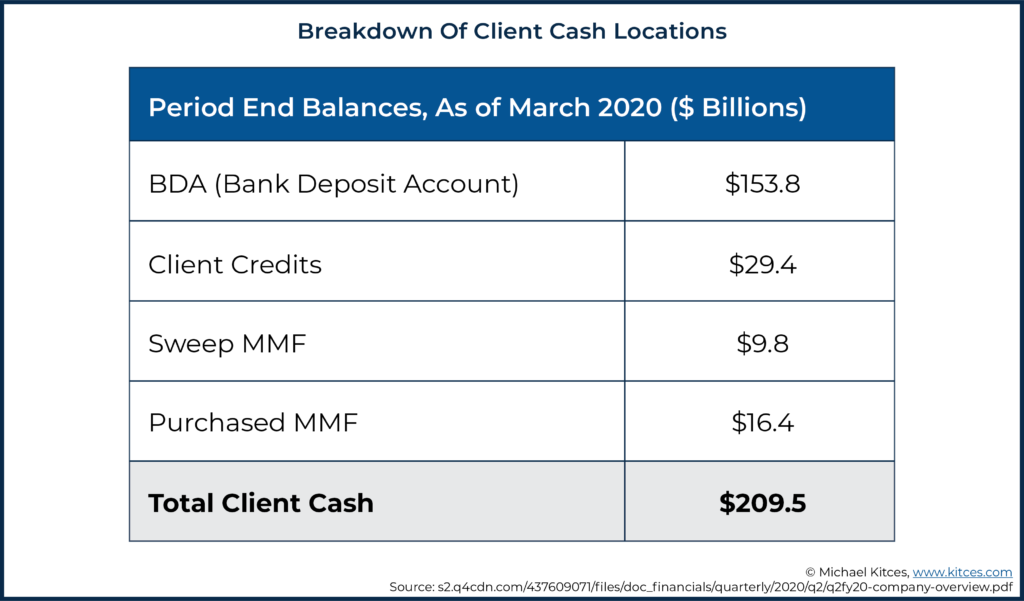

In order to answer these questions, we first turn to a more granular breakdown of where client cash is held, as follows [Page 9 of “Transforming lives and investing for the better” PDF.]:

We can see from the breakdown above that while there are some smaller items, including Client Credits and Money Market Funds, the majority of client cash is held in “BDA.” BDA stands for “Bank Deposit Accounts,” which are TDA’s “sweep accounts” to its own affiliated bank.

Recall that TDA, the brokerage firm, is separate from TD Bank (“TDB”), and the brokerage uses its related bank for cash management purposes. Prior to the Schwab acquisition, TDB (the bank) owned about 43% of TDA (the brokerage), which it agreed to exchange for 13% of Schwab.

TDA’s sweep accounts work like this: Every day, TD client brokerage cash is “swept” into a TD Bank Insured Deposit Account (“IDA”), where that cash earns interest. In the analysis below, we are going to focus on Net Interest Income generated for TDA by these sweep accounts, after accounting for fees and interest paid to clients.

Notably, under a cash sweep account format, dividends and interest are paid into the sweep account, and if the investor wants to buy stock, the cash comes from the sweep account. Which brings up a larger point. Say you have 2 clients, one with all cash, one with all stocks. The stock-purchasing client gets to do a bunch of commission-free trades, which the cash-holding client is effectively subsidizing. Similarly, clients with higher ‘income’ accounts (i.e., those who buy more dividend- and interest-paying investments, that regularly make payments to cash that custodians earn at least some net interest income on via the cash sweep until those dividends and interest are reinvested) are subsidizing those with more low-yield high-growth investment holdings (that remain fully invested and don’t have payments that go to cash for any period of time).

When investing client cash from its sweep program, TD Bank has to consider two things: yield and liquidity. They want to maximize yields and profitability by reinvesting the client cash they’re holding farther out on the yield curve (to earn more of a yield between what the cash generates for TD, and what is paid to clients on the TD platform), but they also want some liquid short-term investments, so that if clients request cash, TDB can raise it quickly and without a costly unwinding of longer-term instruments.

Accordingly, the IDA cash is invested in two tranches: 1) Float Investments; and 2) Fixed Investments. In general, the Float Investments represent lower-yielding, short-term rates, while the Fixed Investments are higher-yielding, longer-term rates. In essence, TDB must guess at the right mix between floating and fixed-rate investments to balance these considerations and maximize the overall profitability of its cash management business.

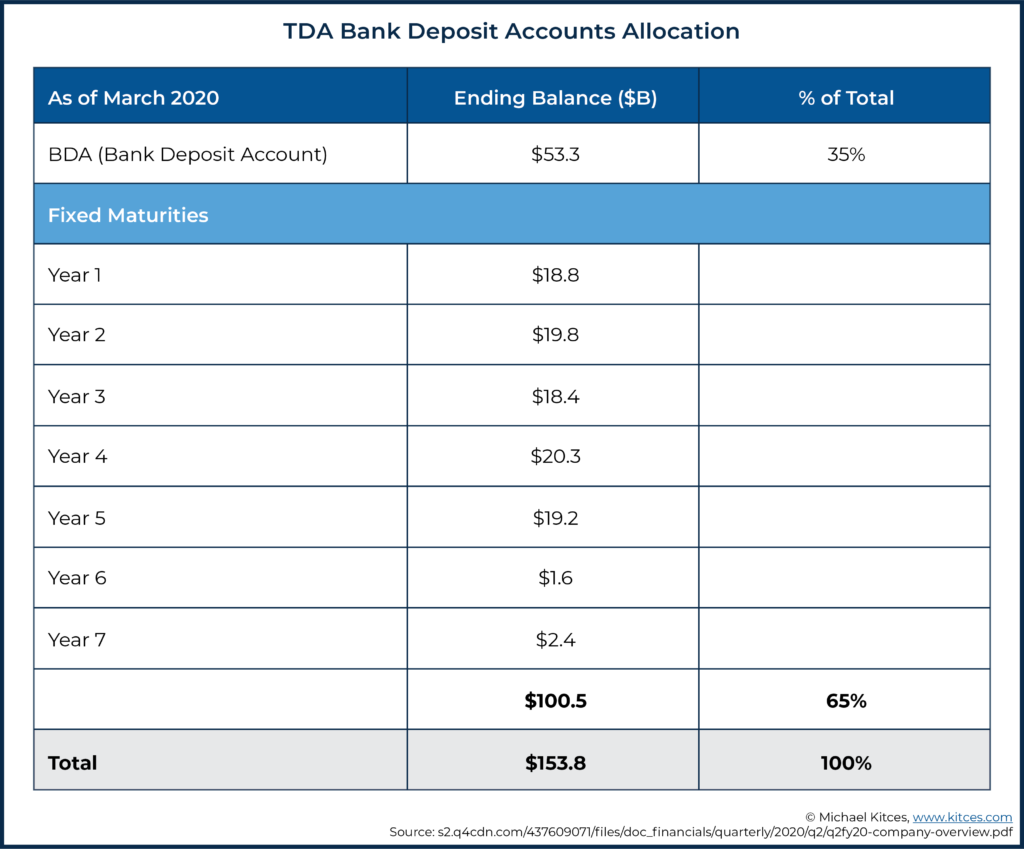

The schedule below sets forth how the $153.8 billion held in Bank Deposit Accounts as part of TDA’s cash sweep program with TDB was allocated, [Page 10 of “Transforming lives and investing for the better” PDF.]:

In essence, then, TD Bank allocated $53.3 billion (or 35%) in Floating Investments, and the balance representing 65% in Fixed Investments, with the goal of maximizing the yield that they generate before making (much-lower) payments back to end TD Ameritrade clients, where the difference between the two is TD Bank’s net interest income.

Notably, one unique aspect of the arrangement between TD Ameritrade and its affiliated cash sweep at TD Bank is that, because TD Bank actually owns TD Ameritrade (and not the other way around), TD Bank effectively used the captive deposits at TD Ameritrade to enhance the bank’s own margins at the expense of TD Ameritrade’s brokerage and custody business. As TD Bank’s own 2019 Annual Report explains, TDB made $464M of revenue primarily from investing activities and this IDA agreement with TDA. Also, TDB noted that in this IDA agreement, “The Bank earns a servicing fee of 25bps on the aggregate average daily balance in the sweep accounts” (all of which is fully disclosed in the IDA agreement).

In other words, TD Bank was charging TD Ameritrade a fee of up to 25 basis points to manage the $53.3B of Float Investments as part of its cash sweep program. Which is important because in March 2020, as the pandemic crashed the stock market, investors raised cash, with allocations going from 11.5% in December 2019 to the 17.0% allocation in March 2020, which was discussed above. Simultaneously, interest rates came down. This had the double-whammy effect of pushing more cash into Float Investments (as a rapid increase of cash in the face of the pandemic was ‘at risk’ for being rapidly deployed after the dust settled, so it couldn’t be locked up into longer-term Fixed Investments), which were 1) incurring more management fees to TD Bank, while 2) earning lower yields due to falling interest rates.

The end result of this arrangement between TD Bank and TD Ameritrade was that it squeezed the profitability of the marginal floating balances to the point where they went negative for TD Ameritrade! Indeed, TDA calculated that, as of April, the net rate earned by TDA on the $53.3 billion in Float Investments, after deducting fees and paying interest to clients, was -5 bps. [Page 10 of “Transforming lives and investing for the better” PDF.]

Schwab understood the dynamic when it was considering acquiring TDA, but it had a solution. It proposed a renegotiation of the management fees contained in the IDA agreement with TD Bank from 25 bps to 15 bps, and a run-off period, whereby Schwab will gradually move those balances away from TD’s Bank into Schwab’s own banks! Because in the case of TD Ameritrade, it’s the Bank that owns (and tries to profit from) the brokerage and custodial platform, while with Schwab, it’s the brokerage and custodial platform that owns (and seeks to profit from) the bank!

This change will have a big impact and will render the TDA cash holdings even more profitable for Schwab. Perhaps incredibly, Schwab estimated that the gains from the renegotiation of the IDA agreement would approximately offset the move to commission-free trading across the combined entities, which is staggering! In other words, the revenue lost from Schwab’s elimination of trading commissions that drove TD Ameritrade to sell itself will be completely offset by the additional profits that Schwab will earn from TD Ameritrade’s cash holdings after the acquisition! Schwab’s ability to reduce this step function effect by reducing TD bank’s management fee, and longer-term, arranging a shift to Schwab internal bank management, was a significant driver for the acquisition.

In fact, in 2019, Schwab had already generated 61% of its $10.7 billion net revenue from net interest sources (i.e., from the small scrape they make on the small percentage of cash in client accounts, writ large over trillions of dollars in their retail and RIA custodial platforms). while for TD Ameritrade, net interest made up 25% of its own $6 billion net revenue. On a combined basis, Schwab’s new cash business after the merger (especially as the management agreement with TD Bank is wound down) will likely be an even larger percentage of its total revenue.

Which means from a business model perspective, many of the leading RIA custodial platforms are effectively banking and cash management platforms with a ‘side hustle’ in RIA custody and brokerage services!

How RIA Custodians Can Invisibly Impair Client Execution With Revenue With Payments For Order Flow

Another source of RIA custodial revenues that can potentially have even more insidious long-term impacts are payments for order flow.

When RIA custodians receive an order from an advisory firm to buy or sell securities for their clients, the RIA custodian can sell this client order flow to high-frequency trading firms, such as Citadel Securities and Virtu Financial. These firms are happy to pay RIA custodians a fee for sending their RIA clients’ buy and sell orders because the high-frequency trading firms earn their own profits by making markets in securities and facilitating market liquidity. But once again, there is no statement investors can point to where these payments are set forth as a percentage of their platform fees. Of course, high-frequency traders are often more efficient traders than the brokers themselves, but the practice still comes at a price.

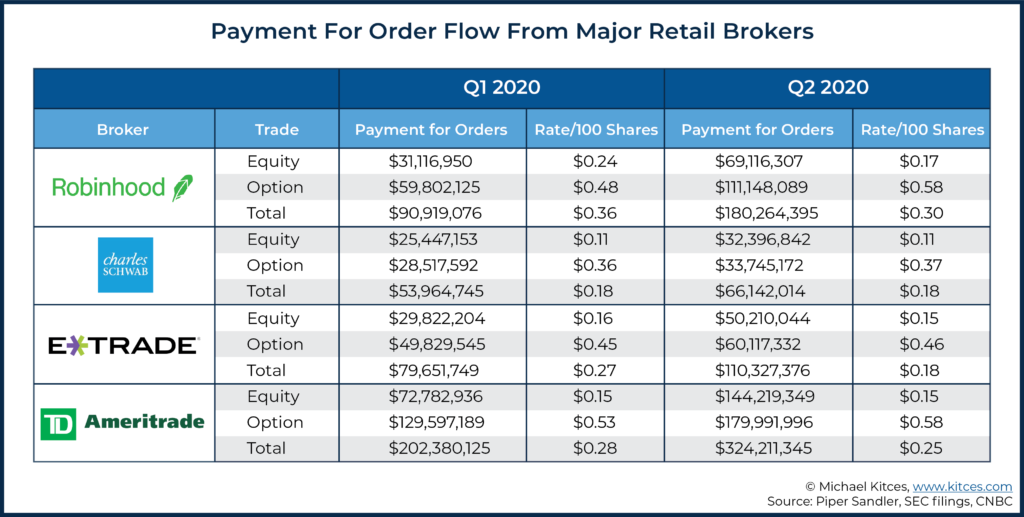

For instance, in August CNBC pointed out that, based on Rule 606 reports, TD Ameritrade, E*Trade, and Charles Schwab received more than $300 million in Payments For Order Flow (PFOF) during the first quarter of 2020. Now it’s true that PFOF may often be resulting in price improvements for this order flow (because the high-frequency trading firm may have actually facilitated better price execution with its market-making efforts). But it’s also true that these are trading costs that are being borne by investors, that they cannot see to evaluate the benefits for themselves.

While we applaud any strategy that could result in pricing improvements for investors, we also think these investors should be aware when they are bearing costs, and know what those costs are, to ensure that RIA custodians are held accountable for continuing to act in the best interests of the RIAs and clients they serve. Simply put, if there’s no clear way for RIAs to track what payments for order flow are being made on their client trades to their RIA custodians, there’s no clear way for RIAs to ensure that their custodians aren’t succumbing to the conflict of interest of accepting the highest PFOF instead of the best for their clients.

After all, these arrangements do lead to serious conflict of interest questions. For example, how do we know if RIA custodians are selling these orders based solely on the quality of the execution, and not shopping for ‘similar’ execution and then choosing based on how much they are receiving from electronic market makers? Today, it’s not clear. What if at some point, RIA custodians are tempted to steer order flow, not to the provider with the best execution for clients, but the one with the highest payment to the RIA custodian… especially since clients and their advisors have little information to know whether or how much it’s even happening (and verify they’re still getting a good deal)? As is, it’s already notable that some RIA custodians and brokerage platforms generate a significantly higher PFOF rate than others, whereas if markets are efficient and order flow payments occur solely from the provider delivering the best execution, shouldn’t order flow pricing be more consistent as well?

More generally, there is a good argument that PFOF practices are exacerbating (in a negative way) systemic execution quality issues for clients.

Consider the overall quality of execution on the exchanges. One way to assess this is via the so-called National Best Bid or Offer (“NBBO”). The NBBO represents, in the aggregate, the highest limit order to buy, combined with the lowest limit order to sell, available across exchange limit books. Since the SEC requires RIA custodians to guarantee this execution price, it represents a standard, or benchmark, against which we can compare execution prices achieved by the RIA custodians.

When RIA custodians sell order flow to high-frequency traders (“HFTs”) for execution, the trades are removed from the NBBO environment, and instead, move off the exchanges and into dark pools. The net effect of this is to remove liquidity from the exchanges. When that happens, what happens to NBBO spreads on the exchanges? They get wider.

Remember, the HFTs must execute at the NBBO price or better. Any price improvement they can achieve is profit for them. Which means ironically, the more order flow that HFTs can purchase for themselves, the more opportunities there are not only to profit directly on the trades but also the wider NBBO spreads on the remaining orders still on the exchanges… which in turn gives them even more room to make more and pay more to the RIA custodians for their client order flow. So what do they do? They buy more order flow, potentially cause NBBO spreads to widen further, profit more from a wider trading range in which they can make their profits, use the additional profits to buy more order flow, and repeat the cycle.

Accordingly, PFOF is growing. In 2008, 26.6% of the listed stock volume traded off the exchanges, while in 2018, 36.3% traded off-exchange.

In other words, as RIA custodians sell more order flow of their RIAs and clients for their own profits, they are gradually lowering the execution quality hurdle they must meet for clients in the first place. This is objectively bad for clients. It erodes the NBBO standard by which brokers are judged, and reduces market liquidity and execution transparency. PFOF is morphing into a systemic problem largely unseen by the investing public, since it is HFTs who are setting prices, and in the process of buying more order flow are lowering the benchmark hurdle that allows them to further expand their trading profits at the expense of clients.

How Much Do RIA Custody Services Actually Cost An RIA And Its Clients?

Given the ubiquity of RIAs “paying” for custody through revenue-sharing agreements controlling what their clients can invest in, net interest on client cash, and payments for client order flow, it’s somewhat stunning that most RIAs can at best only lightly glean what RIA custodians are really charging by taking an indirect look at their public financial statements (at least for the few that are publicly traded and required to make at least some disclosures). Does the average advisor even know (or have the means to know) what the terms are for interest on cash balances and payment for order flow at your custodian?

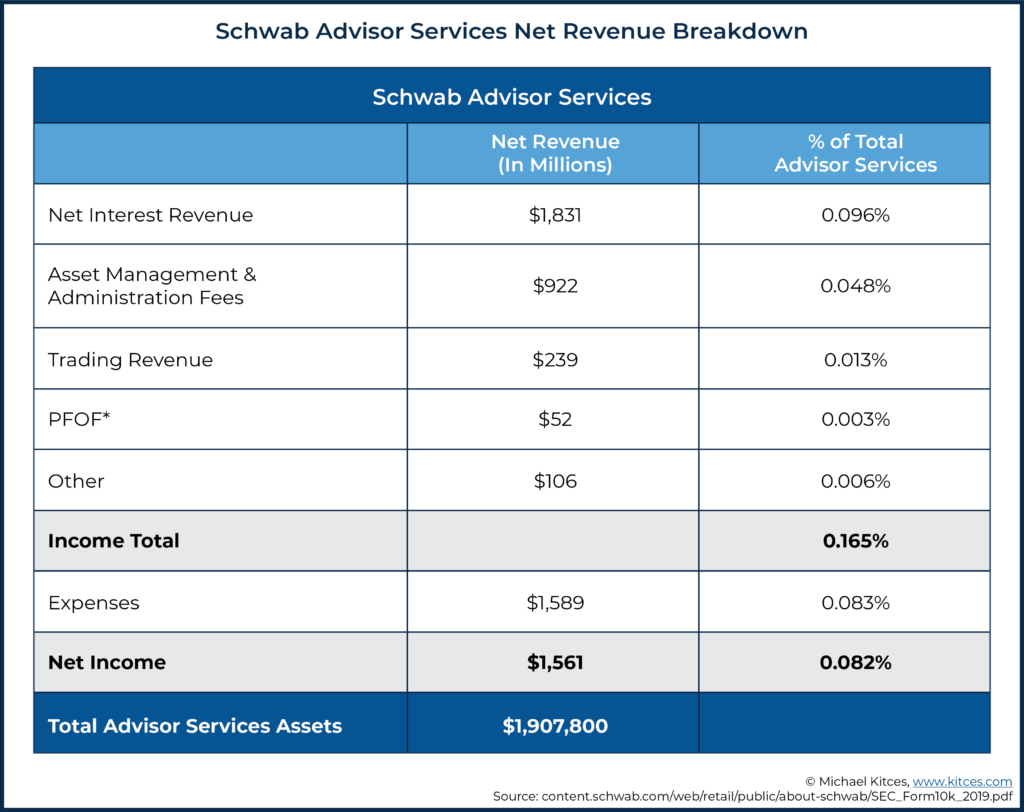

Let’s use Schwab’s latest data in its 10-K as an example. Schwab provided a net revenue breakdown for its Investor Services and Advisor Services. The Advisor Services segment is the RIA services arm.

(Note: Schwab did not segment its total PFOF revenue ($135MM) so we estimated the PFOF revenue of the Advisor Services segment by using the respective percentage of net trading revenue of each segment. Advisor Services’ total net trading revenue is about 39% of Schwab’s total net trading revenue.)

Beyond the net revenue data, Schwab also provided a breakdown of its asset management and administration fees, which includes the various 12b-1 and sub-TA fees it receives for its various No-Transaction-Fee platforms. (Not to mention the additional revenue it can generate when RIAs on the Schwab platform use Schwab’s own proprietary ETFs!)

Nothing is really free, not even “free”. Schwab, on average, is making almost 17bps in revenue from their RIAs’ client assets, which it delivers at a cost of just over 8bps (albeit enhanced by the tremendous economies of scale that Schwab gains from its even-larger retail brokerage business), for a net profit on its Advisor Services of more than 8bps.

It may not be priced directly as a basis point platform fee to clients, but 17bps is the average amount of revenue that Schwab is extracting from RIAs’ clients for its services… including the delivery of “free” custody services to RIAs themselves.

Are Voluntary Trading Commissions Or Other Pay-For-Custody Arrangements A Viable Alternative For RIA Custody Services?

Of course, for those who may not like the answers they see, the question is still, “What’s the alternative. PAY commissions or platform fees?”

The short, simple answer may be, “Yes”. There are a few brokers still offering commission-based trading. For example, Interactive Brokers is offering IBKR Pro, which tries to differentiate on actually charging for execution, and then aims to deliver better execution to customers accordingly.

For instance, according to IHS Markit, a third-party provider of transaction analysis, IBKR Pro’s SmartRouting has $0.47 per 100 shares net US dollar price improvement vs industry’s improvement of $0.15 (based on the NBBO standard discussed above).

For example, if stock A has a $10.00 bid and $10.05 ask on the exchange Y, while on the exchange Z, this same stock has a $10.01 bid and $10.08 ask. If you place a market order to buy, your broker should be able to execute the order on the exchange Y at $10.05 which is the NBBO. However, there are HFTs who would intersect the buy order before the order gets to the exchange. In this case, a HFT will eat a small $10.05 ask and place a $10.08 ask which is now the NBBO. Your larger order will be executed at $10.08. A broker with good execution quality should be able to evaluate fast-changing marketing conditions, re-route and potentially compete with HFTs for your orders, seeking to achieve the best execution and maximize the price improvement for you. (Note that the $0.15 is not comparable to PFOF rates/100 shares set forth above. This net price improvement is after commissions are paid.)

We understand paying commissions seems like a difficult decision to make in a world dominated by headlines about “commission-free” trading. However, you can make a good case that if you can find an RIA custodian who charges you commissions with transparency, or otherwise is willing to charge upfront custody fees, and eliminates hidden or buried fees in other categories, that might be a good choice to make.

We think in this sense, transparency can be achieved by paying commissions (where you know exactly what you’re paying, and what you’re getting in the form of the trade being executed), or alternatively, a basis point fee for custodial services (for those who don’t want the friction of a pay-by-the-trade arrangement), can potentially be a selling point to clients, at least for those who appreciate the benefits of transparency. Which is likely for RIAs, who already disproportionately gain clients with a clear and compelling message about the transparency of the fiduciary model requires that you act in your clients’ best interest.

Ultimately, the costs for custodial work are real, tangible, and can be quantified. Schwab, for instance, has an expense structure of about 8bps on average (albeit writ large over a wide range of RIAs that may be more or less expensive to service, and levered up by its even-larger retail brokerage business as well). There’s nothing necessarily nefarious about RIA custodians making money from asset manager revenue sharing, harvesting yield from cash, or receiving payments for order flow, in that the services they provide do have a real cost and do have to be compensated somehow.

Still, the question arises: why don’t custodians just charge for their services up-front through some form of per trade, basis point, account, or annual fee, instead of burying them into non-transparent practices that end-clients ultimately are paying for anyway… even as they may provide RIAs with an indirect subsidy (as clients are effectively paying the 8bps Schwab platform fee in the form of their own higher costs as end-investors on the platform)?

Will Evolving And Competitive Markets Force RIA Custodians To Re-Price Anyway?

As the pressures on custodial economics are increasing from a zero-interest rate environment (which leaves less room for them to earn net interest income in the first place) and lowered revenues from mutual fund supermarkets as ETFs gain market share (and ETF providers show less willingness to make revenue-sharing payments, as payments must come directly out of their pockets, given the lack of a 12b-1 fees structure for ETFs), something will have to give. And bear in mind that while Schwab may appear to have sizable margins, it is the largest and most scaled player, while all the other competing custodians will likely have materially higher costs… thus why Schwab was able to ‘dictate’ the price of trading commissions down to $0 last year, and why it was able to acquire TD Ameritrade so profitably.

The risk is that custodians will have to reduce costs, potentially in the form of lower service levels to RIAs, or at least/especially small-to-mid-sized RIAs that tend to be less profitable for them by ‘traditional’ non-transparent revenue sources, all of which effectively function on a percentage-of-assets basis (which makes it hard for RIA custodians to be profitable with smaller advisory firms, even as small firms are cross-subsidized by larger advisory firms who don’t necessarily want to pay a more-than-their-own-fair-share payment, either).

No one wants that, as such an outcome can have a significant impact on the long-term growth of the RIA industry as small RIAs may be abandoned by their custodians. Of course, the alternative again is that RIA custodians may begin to charge the requisite fees in the form of technology and account fees, and some are already showing indications that they are beginning to do so for their smaller ‘least profitable’ RIA firms. And notably, despite PR window dressing from Schwabitrade that they won’t do that, their “pledge to the independent advisor community” to maintain a platform that allows all RIAs of any size without asset minimums or custodial fees is exactly that, a pledge – not a guarantee – leaving the door open for themselves to make a change if the troubling economic challenges for traditional RIA custodial revenue models continue and force an increase of fees particularly for smaller firms that are least profitable under Schwab’s model.

Our call to action is for RIAs to stand up in a unified front and demand change, starting with at least a clear disclosure of what, exactly, RIAs and their clients are paying (and what RIA custodians are receiving for conducting RIA clients’ trades and holding clients’ assets). Otherwise, there is a real risk that the financial services industry’s one shining spot – the independent RIA – may succumb to ancient Wall Street practices these retail brokerage custodians desperately cling to. Because, just as with the consumer shift from brokers to RIAs themselves, there is now a clear preference in the marketplace for providers who are transparent with those they serve about what they charge and what they provide for those costs, and are willing to align their business models with those they serve.

For RIAs, the fiduciary choice of whom to work with is up to the advisor.

This article is abstracted from a recent industry white paper authored by TradingFront, which can be downloaded at https://www.tradingfront.com/why-free-trading-really-isn't-free?010